Abstract

Isolated pancreatic metastasis from malignant melanoma is rare. Pancreatic metastasis is difficult to diagnose in patients with unknown primary malignant melanoma. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration plays an important role in confirming the diagnosis. A 67-year-old woman was referred to our institution because of a mass in her pancreas. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a 35-mm mass localized on the pancreatic tail, with low attenuation, surrounded by a high-attenuation rim. Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a hypoechoic mass with central anechoic areas. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the mass was performed, and the pathological diagnosis was malignant melanoma. Intense fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was observed in the pancreatic tail on positron emission tomography–computed tomography. No other malignant melanoma was found. Distal pancreatectomy was performed. Six months postoperatively, positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed high uptake in the left nasal cavity, and biopsy revealed the mass to be a malignant melanoma, indicating that the primary site of the malignant melanoma was the left nasal cavity and that the pancreatic mass and peritoneal lesion were metastases. The patient had survived > 2 years after the distal pancreatectomy. Pancreatic resection of isolated pancreatic metastasis can possibly prolong survival; however, metastatic melanoma usually has poor prognosis.

Keywords: Malignant melanoma, Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP), Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), Case report

Introduction

Pancreatic metastases are rare, ranging from 2 to 5% of pancreatic malignancies [1, 2]. The most common primary malignancies that metastasize to the pancreas are renal, lung, breast, and colon cancer, with sarcoma and melanoma observed less commonly [2–4]. Metastatic melanoma has a poor prognosis; the median survival for patients with stage IV melanoma ranges from 8 to 18 months after diagnosis [5]. Isolated pancreatic metastasis is a rare event that represents about less than 1% of metastatic melanomas [6].

Pancreatic metastases can resemble primary pancreatic malignancies, such as ductal carcinoma or neuroendocrine tumors. Thus, it can be difficult to differentiate pancreatic metastases from primary tumors based only on imaging findings. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) plays an important role in confirming the diagnosis [1]. There are only a few reports on surgically resected pancreatic metastasis of malignant melanoma diagnosed by EUS-FNA [3, 7, 8]. Here, we present a unique case of malignant melanoma with isolated pancreatic metastasis diagnosed by EUS-FNA and was treated with distal pancreatectomy.

Case report

A 67-year-old woman, who had been healthy all her life, presented to the referring hospital with left upper quadrant abdominal pain. Her ultrasonogram and computed tomography (CT) showed a mass in the pancreas, and the patient was referred to our institution for further examination.

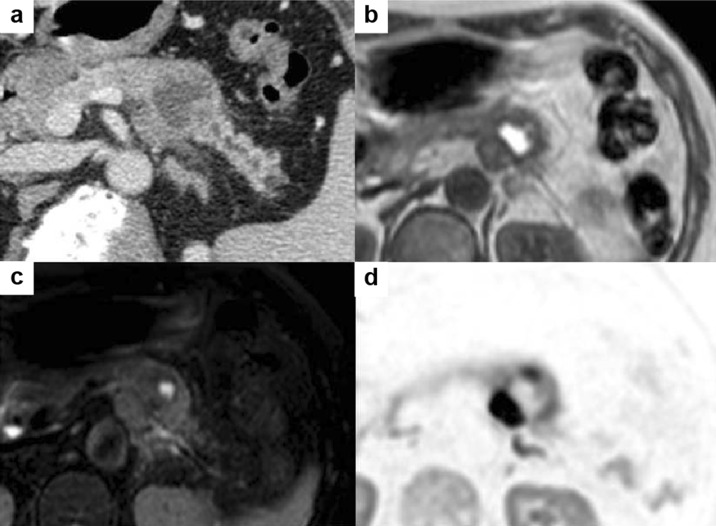

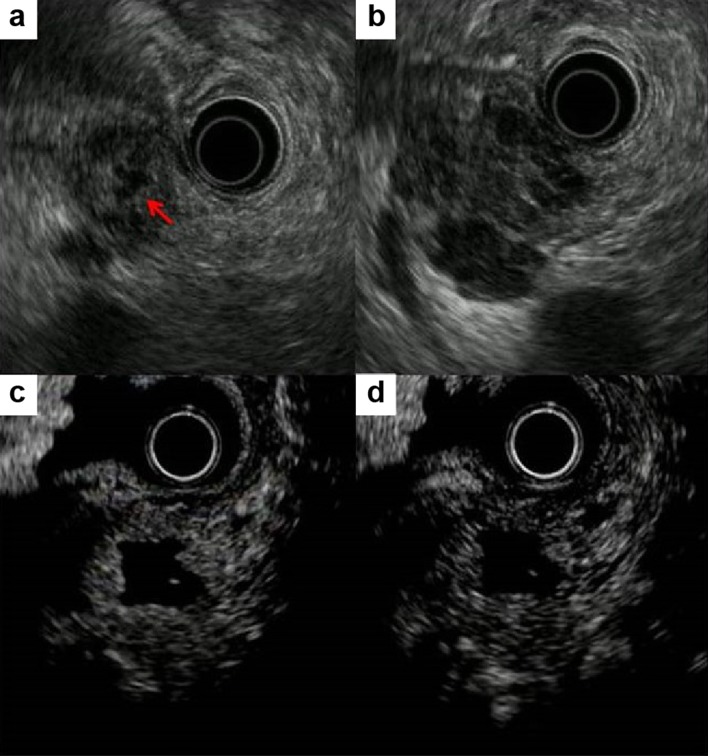

Enhanced CT revealed that the mass was localized to the tail of the pancreas, with pancreatic ductal dilatation. The mass was a rounded, well-defined lesion with low attenuation, surrounded by a high-attenuation rim (Fig. 1a). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the center of the mass was hyperintense on T1-weighted image and hypointense on T2-weighted image (Fig. 1b, c). The diffusion-weighted image showed a hyperintense peripheral rim of the mass (Fig. 1d). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram demonstrated smooth narrowing and displacement of the pancreatic duct with upstream dilatation (Fig. 2). EUS revealed the 35-mm mass to be hypoechoic and heterogeneous with central anechoic areas (Fig. 3a, b). Contrast-enhanced EUS (CE-EUS) was conducted using an electronic radial-type endoscope (GF-UE260; Olympus, Japan) and perflubutane as ultrasound contrast agent. CE-EUS showed isoenhancement during the 20-s phase (Fig. 3c) and hypoenhancement during the 120-s phase (Fig. 3d) of the peripheral rim of the mass with central non-enhancement.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography image. a Mass in the tail of the pancreas with pancreatic ductal dilation. The central mass is hyperintense on T1-weighted image (b) and hypointense on T2-weighted image (c). d Peripheral rim of the mass is hyperintense on diffusion-weighted image

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram revealed smooth narrowing and displacement of the pancreatic duct with upstream dilatation

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed hypoechoic and homogenous heterogeneous mass (a) with central anechoic areas (b, arrow). Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography shows isoenhancement at 20 s (c) and hypoenhancement at 120 s (d) with central non-enhancement of the peripheral rim of the mass

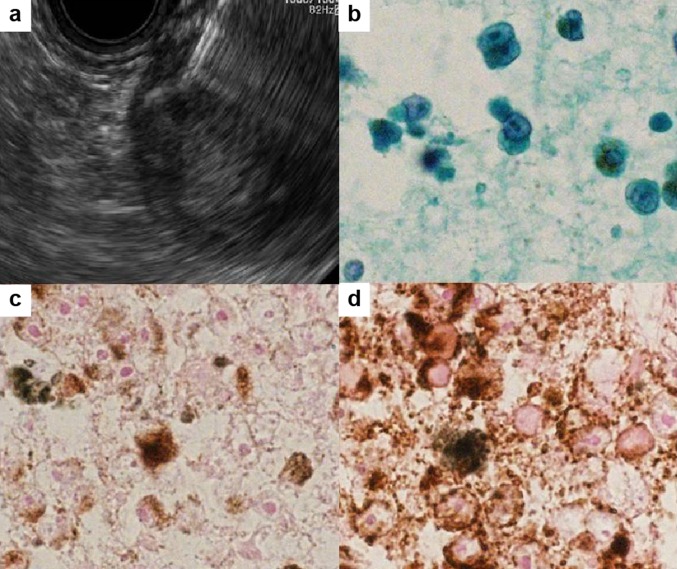

Cytological analysis obtained by EUS-FNA with a 22-gauge needle (Fig. 4a) revealed a large nucleus and a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio in the cells, with brown pigmentation (Fig. 4b). The cells were positive for Melan A and Human Melanoma Black 45 (HMB-45) and were negative for S100 on cell-block immunocytochemical analysis (Fig. 4c, d). Thus, the patient was diagnosed as having malignant melanoma.

Fig. 4.

a Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the peripheral rim of the mass. b Cytologic results revealed a large nucleus and a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio in the cells, with brown pigmentation. Immunocytochemical staining with Melan A (c) and Human Melanoma Black 45 (d)

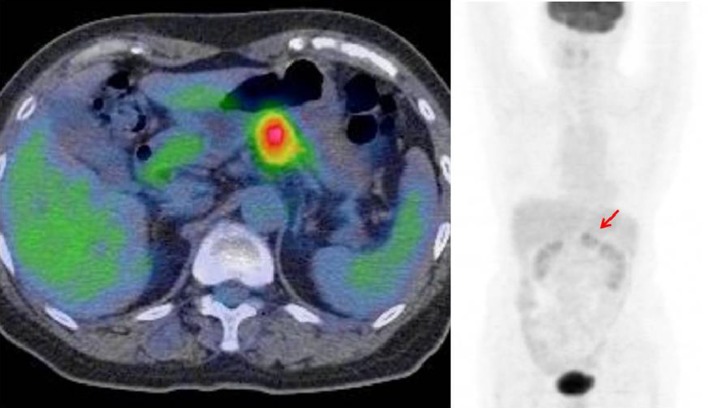

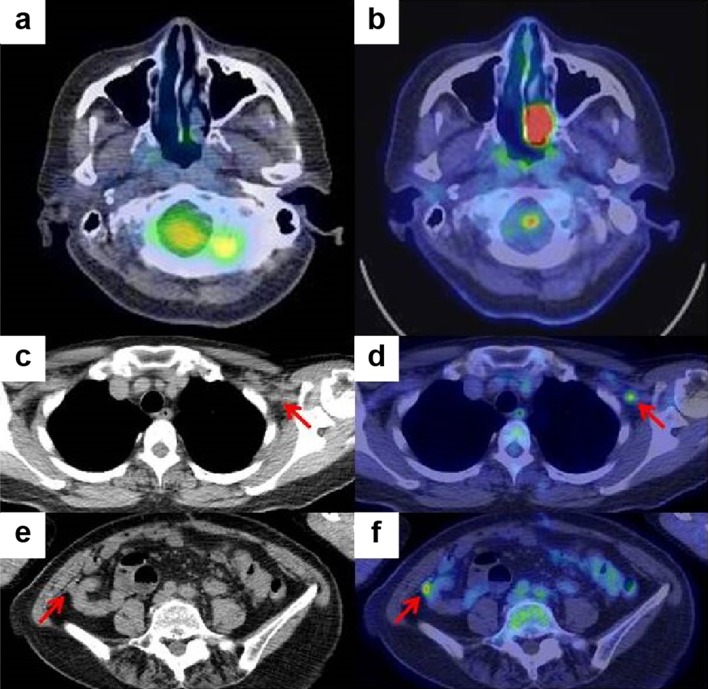

Since primary pancreatic malignant melanoma has never been reported before, we suspected metastatic malignant melanoma of the pancreas. However, intense fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was observed only in the tail of the pancreas on positron emission tomography–CT (PET-CT) (Fig. 5). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy did not reveal any specific findings. The primary site could not be identified by dermatological, ophthalmological, or gynecological examination.

Fig. 5.

Intense fluorodeoxyglucose uptake only in the body and tail of the pancreas (arrow)

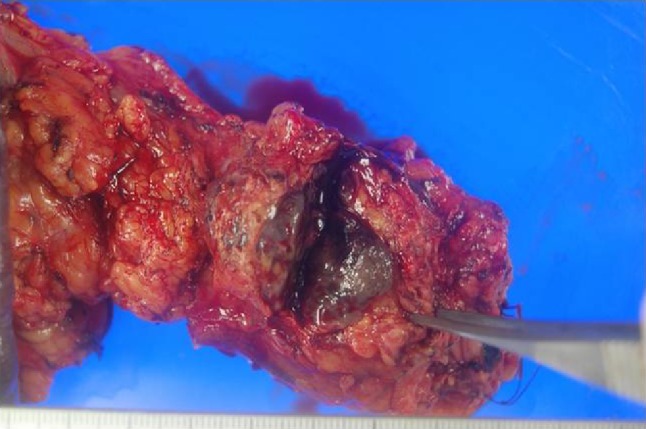

Distal pancreatectomy was performed. Histological examination of the surgical specimen revealed malignant melanoma with central necrosis (Figs. 6, 7). The resection specimen stained for Melan A and HMB-45, but not for S100. The patient underwent interferon-alfa treatment as an adjuvant therapy. Six months postoperatively, the follow-up PET-CT showed high uptake in the left nasal cavity, left infraclavicular lymph, and peritoneum (Fig. 8). On fiber-optic laryngoscopy, a whitish mass was detected in the left nasal cavity, which was determined to be a malignant melanoma. Although melanin was unclear in the nasal cavity biopsy specimen, cell shape and immunohistochemistry findings were the same as those in the resected surgical specimen. The primary site of the malignant melanoma was the left nasal cavity, and the pancreatic mass, left infraclavicular lymph, and peritoneal lesion were metastases. Nivolumab was started; thereafter, the treatment was switched to pembrolizumab. The patient had survived for more than 2 years after the distal pancreatectomy.

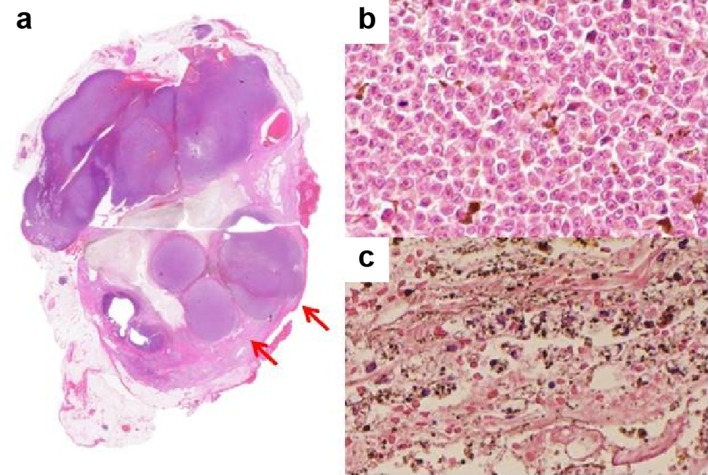

Fig. 6.

Resected surgical specimen showing a black–brown mass in the tail of the pancreas

Fig. 7.

a Loupe image of the resection specimen. The peripheral rim of the mass has nodular components (arrows). b Tumor cells in the peripheral rim of the mass have anisokaryosis and clear nuclei with melanin production. c Center of the mass was necrotic

Fig. 8.

Positron emission tomography–computed tomography image of the nasal cavity before (a) and after surgery (b). Plane computed tomography and positron emission tomography–computed tomography images after surgery revealed left infraclavicular lymph node metastasis (c, d) and a small peritoneal nodule (e, f)

Discussion

Malignant melanoma usually metastasizes to the gastrointestinal tract, and metastatic malignant melanoma usually affects multiple sites. Isolated organ metastasis is unusual; specifically, metastasis to the pancreas is extremely rare (< 1%) [6]. There are 76 cases of pancreatic metastasis from malignant melanoma reported in English (Table 1). The major primary site is cutaneous and ocular. Meanwhile, there are only three cases of pancreatic metastasis from nasal cavity malignant melanoma, including our case [9, 10]. Sometimes, the primary lesion of melanoma is difficult to identify during pretreatment evaluation. In our case, the primary site was identified by PET-CT 6 months postoperatively, even though PET-CT is only effective for detecting primary tumors or cancers of unknown primary.

Table 1.

Metastatic malignant melanoma of pancreas reported in the English literature

| Authors | Year of publication | Age | Sex | Case | Primary site | Location in the pancreas | Tumor size (cm) | Diagnostic modality | Surgery | Follow-up (month) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Das Gupta et al. [21] | 1964 | 44 | Female | 2 | Cutaneous | Body and tail | NR | Exploratory laparotomy | No operation | 2 | Dead |

| 28 | Male | Cutaneous | Body and tail | NR | Exploratory laparotomy | DP | 10 | Dead | |||

| Johansson et al. [22] | 1970 | 67 | Female | 1 | Ocular | Head | NR | Biopsy | PD | 11 | Alive |

| Bianca et al. [23] | 1991 | 48 | Male | 1 | Unknown | Head | 3 | FNA | PD | 12 | Alive |

| Brodish et al. [24] | 1993 | 75 | Female | 1 | Cutaneous | Tail | 5 | CT | DP | 12 | Alive |

| Rütter et al. [9] | 1994 | 55 | Male | 1 | Unknown (1 year after surgery, melanoma detected in nasal cavity and nasopharynx) | Head | 2.5 | ERCP | DP | 12 | Alive |

| Sobesky et al. [25] | 1997 | 32 | Female | 1 | Thoracic melanoma | Diffuse infiltration | NR | ERCP, biopsy | No operation | 1.5 | Dead |

| Harrison et al. [26] | 1997 | NR | NR | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Medina-Franco et al. [27] | 1999 | 60 | Male | 1 | Unknown | Head | 8 | CT, US | PD | 6 | Dead |

| Wood et al. [19] | 2001 | NR | NR | 8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Curative resection or palliative resection | Median 23.8 | |

| NR | NR | 20 | NR | NR | NR | NR | no operation | Median 15.2 | |||

| Hiotis et al. [28] | 2002 | NR | NR | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NK | PD | NR | Dead |

| Camp et al. [29] | 2002 | 62 | Female | 1 | Ocular | Body | 5 | CT, PET-CT | DP | 20 | Alive |

| Dewitt et al. [30] | 2003 | 33 | Male | 2 | Unknown | Head | 5 | EUS-FNA | Palliative gastrojejunostomy | 6 | Dead |

| 83 | Female | Unknown | Tail | 3 | EUS-FNA | No operation | 10 | Alive | |||

| Mizushima et al. [31] | 2003 | 51 | Female | 1 | Cutaneous | Head | 5 | Biopsy | No operation | NR | NR |

| Nikfarjam et al. [32] | 2003 | 45 | Male | 2 | Ocular | Head | 3 | CT, MRI, PET-CT etc. | PD | 6 | Alive |

| 55 | Male | Ocular | Head, body, tail | NR | CT, PET-CT etc. | TP | 7 | Alive | |||

| Carboni et al. [33] | 2004 | 55 | Female | 1 | Cutaneous | Head | 8 | Biopsy | PD | 4 | Dead |

| Crippa et al. [34] | 2006 | 36 | Female | 1 | NR | Head | NR | NR | PD | 14 | Dead |

| Belágyi et al. [35] | 2006 | 28 | Female | 1 | Ocular | Body | NR | CT | Pancreatic enucleation etc. | 4 | Dead |

| Eidt et al. [36] | 2007 | NR | NR | 4 | NR | NR | 8 | NR | PD | 76 | Alive |

| NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 | NR | PD | 30 | Alive | |||

| NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 | NR | PD | 12 | Dead | |||

| NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 | NR | PD | 25 | Dead | |||

| Reddy et al. [37] | 2008 | NR | NR | 3 | NR | NR | Median size 4 | NR | NR | Median 10.8 | |

| Dumitraşcu et al. [7] | 2008 | 43 | Female | 1 | Ocular | Body | 2 | EUS-FNA | CP | 12 | Alive |

| Lanitis et al. [38] | 2010 | 69 | Male | 1 | Cutaneous | Head | 4.5 | CT | PD | 96 | Alive |

| He et al. [39] | 2010 | 39 | Male | 1 | Ocular | Tail | 18 | CT, MRI, ERCP etc. | DP | 25 | Alive |

| Vagefi et al. [8] | 2010 | 57 | Female | 1 | Ocular | Tail | 2.2 | EUS-FNA | DP | NR | NR |

| Portale et al. [4] | 2011 | 43 | Female | 1 | Unknown | Tail | 1.7 | US, CT, PET-CT | DP | NR | NR |

| Moszkowicz et al. [40] | 2011 | 44 | Female | 1 | Cutaneous | Uncinate process, Cephalo-isthmic junction | 1.3, 0.9 | Biopsy under EUS | PD | NR | NR |

| Sperti et al. [41] | 2011 | 48 | Male | 1 | Unknown | Body | 2.9 | CT | DP | 24 | Dead |

| Goyal et al. [18] | 2012 | 47 | Female | 5 | Cutaneous | Head | 3 | ERCP-assisted biopsy | PD | 15 | Dead |

| 73 | Female | Cutaneous | Head | 4 | CT | PD | 3 | Dead | |||

| 58 | Female | Unknown | Head | 10 | CT-guided biopsy | PD | 11.4 | Dead | |||

| 28 | Female | Cutaneous | Head | 2 | PET-CT | PD | 4.5 | Dead | |||

| 69 | Male | Unknown | Tail | 4.5 | Biopsy | DP | 26 | Dead | |||

| Larsen et al. [2] | 2013 | 32 | Female | 1 | Cutaneous | Head | NR | CT | PD | 228 | Alive |

| Birnbaum et al. [5] | 2013 | 45 | Female | 1 | Cutaneous | Head | 6 | Biopsy | PD | 19 | Alive |

| Sugimoto et al. [10] | 2013 | 46 | Male | 1 | Nasal cavity | Body | 3.3 | CT, PET-CT | DP | 10 | Dead |

| Solmaz et al. [42] | 2014 | 59 | Male | 1 | Cutaneous | Head | 3.8 | Biopsy | No operation | NR | NR |

| Jana et al. [1] | 2015 | 75 | Male | 1 | Cutaneous | Head, body | 2.4, 1.4, 1, 0.6 | EUS-FNA | No operation | NR | NR |

| De Moura et al. [3] | 2016 | 58 | Female | 1 | Ocular | Head, neck | 3.1 | EUS-FNA | PD | NR | NR |

| Nadal et al. [43] | 2016 | 57 | Female | 1 | Ocular | Tail | 2 | EUS-FNA | NR | NR | NR |

| Ben Slama et al. [44] | 2017 | 55 | Female | 1 | Unknown | Head | 5.5 | CT, MRI | PD | 15 | Alive |

| Liu et al. [45] | 2018 | 54 | Male | 1 | Cutaneous | Head | 3.1 | CT | PD | 6 | Alive |

| Current | 2019 | 67 | Female | 1 | Nasal cavity | Body | 3.5 | EUS-FNA | DP | 24 | Alive |

NR not reported, PD pancreatoduodenectomy, DP distal pancreatectomy, TP total pancreatectomy, CP central pancreatectomy

Despite technological advances, preoperative diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic tumor is sometimes difficult [11]. Metastatic lesions from malignant melanoma have hypervascularity on contrast-enhanced CT and MRI [12]. The blood supply to metastatic lesions is carried from the surrounding organs; therefore, the surrounding tissue of the large lesion receives more blood supply than the central area, resulting in rim enhancement, especially in lesions larger than 1.5 cm. The same could be said in our case, as a high-attenuation rim was revealed on enhanced CT. EUS provided us with high-quality images to examine the pancreas and nearby structures. In general, pancreatic metastases on EUS have regular margins and appear as homogenous structures that are hypoechoic compared with the surrounding pancreas [13]. In our case, EUS revealed the mass to be hypoechoic and homogenous with the central anechoic areas. Few studies have reported on CE-EUS findings of pancreatic metastatic lesion. Pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma tends to show hyperenhancement, whereas malignant melanoma may or may not show hyperenhancement [13–15]. The lack of characteristic findings makes diagnosis of metastatic malignant melanoma by CE-EUS difficult.

To confirm the diagnosis of pancreatic metastatic lesions, pathological examination is necessary. EUS-FNA plays an important role in providing cytological/histological diagnosis, and it is extremely useful in identifying pancreatic metastases. To distinguish pancreatic metastases from a primary carcinoma accurately, effective sampling and immunocytochemistry are needed [1, 3, 6]. EUS-FNA with rapid on-site evaluation provides effective sampling, because a cytopathologist can ensure that the samples are adequate for assessment [16]. Immunohistochemical analysis has been shown to be useful in identifying metastatic melanoma; the sensitivity of S100, Melan A, and HMB-45 are reported to be 97–100%, 75–92%, and 69–93%, respectively. The specificity of S100 and Melan A is reported to be 75–87% and 95–100%, respectively [17]. In our case, Melan A and HMB-45 were positive.

The prognosis of patients with malignant melanoma metastatic to the pancreas is unknown, although metastatic melanoma usually indicates poor prognosis [5]. There are few experiences with pancreatic resection for isolated pancreatic metastases, and pancreatic resection is controversial. Some studies have shown that complete surgical resection of a localized metastatic disease can prolong survival [5, 18]. However, Wood et al. [19] reported 28 patients with isolated pancreatic metastases from malignant melanoma and found that the 5-year survival rate of pancreatic resection (performed in 8 patients) was 37.5% (median survival, 23.8 months), as compared with 23% (median survival, 15.2 months) of the 20 patients treated with non-resection. It is critical that surgery should be performed only when a complete resection is possible. Therefore, exhaustive preoperative staging is needed to confirm both the absence of local invasion of the major vasculature and the absence of distant metastasis. PET scan has a high sensitivity and specificity for detecting metastasis from malignant melanoma [20]. In our case, PET-CT also had an important role; preoperative PET-CT identified the pancreatic tail mass, and the 6-month postoperative PET-CT showed high uptake in the left nasal cavity and peritoneum.

In conclusion, this unique case of isolated pancreatic metastasis from malignant melanoma was conclusively proven with EUS-FNA prior to the diagnosis of the primary lesion. Broad differential diagnoses should be considered when faced with inconclusive imaging studies of pancreatic tumors. In such cases, EUS-FNA is useful in providing a definitive diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Hiroko Sugimoto from the Department of Pathology, Matsusaka Chuo General Hospital, Matsusaka, Mie, Japan, for helpful discussions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or financial arrangement with any company.

Human rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008(5).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jana T, Caraway NP, Irisawa A, et al. Multiple pancreatic metastases from malignant melanoma: conclusive diagnosis with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:145–148. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.156746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen AK, Krag C, Geertsen P, et al. Isolated malignant melanoma metastasis to the pancreas. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013;1:e74. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Moura DT, Chacon DA, Tanigawa R, et al. Pancreatic metastases from ocular malignant melanoma: the use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration to establish a definitive cytologic diagnosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:332. doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-1121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portale TR, Di Benedetto V, Mosca F, et al. Isolated pancreatic metastasis from melanoma. Case report. G Chir. 2011;32:135–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbaum DJ, Moutardier V, Turrini O, et al. Isolated pancreatic metastasis from malignant melanoma: is pancreatectomy worthwhile? J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2013;5:82–84. doi: 10.4103/2006-8808.128733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang JC, Roh MH. Metastases to the pancreas encountered on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:1248–1252. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0200-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumitraşcu T, Dima S, Popescu C, et al. An unusual indication for central pancreatectomy—late pancreatic metastasis of ocular malignant melanoma. Chirurgia. 2008;103:479–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vagefi PA, Stangenberg L, Krings G, et al. Ocular melanoma metastatic to the pancreas after a 28-year disease-free interval. Surgery. 2010;148:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rütter JE, De Graaf PW, Kooyman CD, et al. Malignant melanoma of the pancreas: primary tumour or unknown primary? Eur J Surg. 1994;160:119–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugimoto M, Gotohda N, Kato Y, et al. Pancreatic resection for metastatic melanoma originating from the nasal cavity: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yagi T, Hashimoto D, Taki K, et al. Surgery for metastatic tumors of the pancreas. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:31. doi: 10.1186/s40792-017-0308-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsitouridis I, Diamantopoulou A, Michaelides M, et al. Pancreatic metastases: CT and MRI findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010;16:45–51. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.1996-08.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fusaroli P, D’Ercole MC, De Giorgio R, et al. Contrast harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography in the characterization of pancreatic metastases (with video) Pancreas. 2014;43:584–587. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fusaroli P, Spada A, Mancino MG, Caletti G. Contrast harmonic echo–endoscopic ultrasound improves accuracy in diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamashita Y, Kato J, Ueda K, et al. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography for pancreatic tumors. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:491782. doi: 10.1155/2015/491782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamao K, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNAB): past, present, and future. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1013–1023. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyal J, Lipson EJ, Rezaee N, et al. Surgical resection of malignant melanoma metastatic to the pancreas: case series and review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:431–436. doi: 10.1007/s12029-011-9320-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood TF, DiFronzo LA, Rose DM, et al. Does complete resection of melanoma metastatic to solid intra-abdominal organs improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:658–662. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinne D, Baum RP, Hör G, Kaufmann R. Primary staging and follow-up of high risk melanoma patients with whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: results of a prospective study of 100 patients. Cancer. 1998;82:1664–1671. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980501)82:9<1664::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta TD, Brasfield R. Metastatic melanoma: a clinicopathological study. Cancer. 1964;17:1323–1339. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196410)17:10<1323::aid-cncr2820171015>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson H, Krause U, Olding L. Pancreatic metastases from a malignant melanoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1970;5:573–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bianca A, Carboni N, Di Carlo V, et al. Pancreatic malignant melanoma with occult primary lesion. A case report. Pathologica. 1991;84:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brodish RJ, McFadden DW. The pancreas as the solitary site of metastasis from melanoma. Pancreas. 1993;8:276–278. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobesky R, Duclos-Vallée JC, Prat F, et al. Acute pancreatitis revealing diffuse infiltration of the pancreas by melanoma. Pancreas. 1997;15:213–215. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199708000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison LE, Merchant N, Cohen AM, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for nonperiampullary primary tumors. Am J Surg. 1997;174:393–395. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medina-Franco H, Halpern NB, Aldrete JS. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for metastatic tumors to the periampullary region. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiotis SP, Klimstra DS, Conlon KC, et al. Results after pancreatic resection for metastatic lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:675–679. doi: 10.1007/BF02574484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camp R, Lind DS, Hemming AW. Combined liver and pancreas resection with biochemotherapy for metastatic ocular melanoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:519–521. doi: 10.1007/s005340200066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewitt JM, Chappo J, Sherman S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of melanoma metastatic to the pancreas: report of two cases and review. Endoscopy. 2003;35:219–222. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizushima T, Tanioka H, Emori Y, et al. Metastatic pancreatic malignant melanoma: tumor thrombus formed in portal venous system 15 years after initial surgery. Pancreas. 2003;27:201–203. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200308000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikfarjam M, Evans P, Christophi C. Pancreatic resection for metastatic melanoma. HPB. 2003;5:174–179. doi: 10.1080/13651820310015284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carboni F, Graziano F, Lonardo MT, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic metastatic melanoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2004;23:539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crippa S, Angelini C, Mussi C, et al. Surgical treatment of metastatic tumors to the pancreas: a single center experience and review of the literature. World J Surg. 2006;30:1536–1542. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belágyi T, Zsoldos P, Makay R, et al. Multiorgan resection (including the pancreas) for metastasis of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Pancreas. 2006;7:234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eidt S, Jergas M, Schmidt R, et al. Metastasis to the pancreas—an indication for pancreatic resection? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:539–542. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy S, Edil BH, Cameron JL, et al. Pancreatic resection of isolated metastases from nonpancreatic primary cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3199–3206. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanitis S, Papaioannou N, Sgourakis G, et al. Prolonged survival after the surgical management of a solitary malignant melanoma lesion within the pancreas: a case report of curative resection. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2010;19:453–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He MX, Song B, Jiang H, et al. Complete resection of isolated pancreatic metastatic melanoma: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4621–4624. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moszkowicz D, Peschaud F, El Hajjam M, et al. Preservation of an intra-pancreatic hepatic artery during duodenopancreatectomy for melanoma metastasis. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33:547–550. doi: 10.1007/s00276-010-0770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sperti C, Polizzi ML, Beltrame V, et al. Pancreatic resection for metastatic melanoma. Case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2011;42:302–306. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solmaz A, Yigitbas H, Tokoçin M, et al. Isolated pancreatic metastasis from melanoma: a case report. J Carcinog Mutagen. 2014;5:202. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nadal E, Burra P, Mescoli C, et al. Pancreatic melanoma metastasis diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided SharkCore biopsy. Endoscopy. 2016;1:E208–E209. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-109050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben SS, Bacha D, Bayar R, et al. Pancreatic resection for isolated metastasis from melanoma of unknown primary. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2017;80:323–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X, Feng F, Wang T, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for metastatic pancreatic melanoma: a case report. Medicine. 2018;97:e12940. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]