Abstract

Background

Benign paroxsymal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a syndrome characterised by short‐lived episodes of vertigo associated with rapid changes in head position. It is a common cause of vertigo presenting to primary care and specialist otolaryngology (ENT) clinics. BPPV of the posterior canal is a specific type of BPPV for which the Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre is a verified treatment. A range of modifications of the Epley manoeuvre are used in clinical practice, including post‐Epley vestibular exercises and post‐Epley postural restrictions.

Objectives

To assess whether the various modifications of the Epley manoeuvre for posterior canal BPPV enhance its efficacy in clinical practice.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane ENT Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; Web of Science; BIOSIS Previews; Cambridge Scientific Abstracts; ICTRP and additional sources for published and unpublished trials. The date of the search was 15 December 2011.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of modifications of the Epley manoeuvre versus a standard Epley manoeuvre as a control in adults with posterior canal BPPV diagnosed with a positive Dix‐Hallpike test. Specific modifications sought were: application of vibration/oscillation to the mastoid region, vestibular rehabilitation exercises, additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre and post‐treatment instructions relating to movement restriction.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected studies from the search results and the third author reviewed and resolved any disagreement. Two authors independently extracted data from the studies using standardised data forms. All authors independently assessed the trials for risk of bias.

Main results

The review includes 11 trials involving 855 participants. A total of nine studies used post‐Epley postural restrictions as their modification of the Epley manoeuvre. There was no evidence of a difference in the results for post‐treatment vertigo intensity or subjective assessment of improvement in individual or pooled data. All nine trials included the conversion of a positive to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test as an outcome measure. Pooled data identified a significant difference from the addition of postural restrictions in the frequency of Dix‐Hallpike conversion when compared to the Epley manoeuvre alone. In the experimental group 88.7% (220 out of 248) patients versus 78.2% (219 out of 280) in the control group converted from a positive to negative Dix‐Hallpike test (risk ratio (RR) 1.13, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05 to 1.22, P = 0.002). No serious adverse effects were reported, however three studies reported minor complications such as neck stiffness, horizontal BPPV, dizziness and disequilibrium in some patients.

There was no evidence of benefit of mastoid oscillation applied during the Epley manoeuvre, or of additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre. No adverse effects were reported.

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence supporting a statistically significant effect of post‐Epley postural restrictions in comparison to the Epley manoeuvre alone. However, it important to note that this statistically significant effect only highlights a small improvement in treatment efficacy. An Epley manoeuvre alone is effective in just under 80% of patients with typical BPPV. The additional intervention of postural restrictions has a number needed to treat (NNT) of 10. The addition of postural restrictions does not expose the majority of patients to risk of harm, does not pose a major inconvenience, and can be routinely discussed and advised. Specific patients who experience discomfort due to wearing a cervical collar and inconvenience in sleeping upright may be treated with the Epley manoeuvre alone and still expect to be cured in most instances.

There is insufficient evidence to support the routine application of mastoid oscillation during the Epley manoeuvre, or additional steps in an 'augmented' Epley manoeuvre. Neither treatment is associated with adverse outcomes. Further studies should employ a rigorous randomisation technique, blinded outcome assessment, a post‐treatment Dix‐Hallpike test as an outcome measure and longer‐term follow‐up of patients.

Keywords: Humans, Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, Exercise Therapy, Exercise Therapy/methods, Immobilization, Immobilization/instrumentation, Immobilization/methods, Patient Positioning, Patient Positioning/methods, Posture, Posture/physiology, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Vertigo, Vertigo/therapy, Vibration, Vibration/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Modifications of the Epley manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

Benign paroxsymal positional vertigo (BPPV) is caused by rapid changes in head position. The person feels they or their surroundings are moving or rotating. Common causes appear to be head trauma or types of ear infection. BPPV can be caused by particles in the semicircular canal of the inner ear that continue to move when the head has stopped moving. This causes a sensation of ongoing movement that conflicts with other sensory information. The Epley manoeuvre has been shown to improve the symptoms of BPPV. This is a procedure that moves the head and body in four different movements and is designed to remove the particles (causing the underlying problem) from the semicircular canals in the inner ear. A range of modifications of the Epley manoeuvre are now used in clinical practice, including applying vibration to the mastoid bone behind the ear during the manoeuvre, having a programme of balance exercises after the manoeuvre has been done, and placing restrictions on a patient's position (for example, not sleeping on the affected ear for a few days). There are also a number of different ways to do the manoeuvre.

We included 11 studies in this review, with a total of 855 participants. Nine studies looked at post‐treatment postural restrictions (using a neck brace/head movement restrictions/instructions to sleep upright) following the Epley manoeuvre. There was a statistically significant difference found when these restrictions were compared to a control treatment of the Epley manoeuvre alone. Although there was a difference between the groups, adding postural restrictions conferred only a small additional benefit since the Epley manoeuvre was effective alone in just under 80% of patients. Four of the studies reported minor complications such as neck stiffness, horizontal BPPV (a subtype of BPPV which is similar to posterior canal BPPV, but has some distinct differences in terms of the signs and symptoms), dizziness and disequilibrium (the feeling of unsteadiness on ones feet) in some patients.

Additionally, two studies looked into the application of oscillation/vibration to the mastoid region during the Epley manoeuvre compared to control; the intervention produced no difference in outcome between these groups. One study that also researched post‐treatment postural restrictions looked into extra steps in the Epley manoeuvre. Compared to the control treatment there were no significant differences in outcomes.

No serious adverse effects were reported in any of the studies in the review. The results should be interpreted carefully and further trials are needed.

Background

Description of the condition

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a syndrome characterised by short‐lived episodes of vertigo (a sensation of instability, often with a sensation of rotation) associated with rapid changes in head position. It is a common cause of vertigo presenting to primary care and specialist otolaryngology, neuro‐otology, neurology and audiological clinics. There are a number of aetiologies associated with BPPV. Common causes appear to be head trauma (17%) and vestibular neuritis (inflammation or infection of the nerve supplying the vestibule; an important part of the balance system) (15%) (Baloh 1987). Other putative causes include vertebrobasilar ischaemia (reduced blood flow in the area of the brain supplied by the basilar artery), labyrinthitis (inflammation or infection of the inner ear), as a complication of middle ear surgery and following periods of prolonged bed rest. However, most cases appear to be idiopathic.

Incidence and prevalence

Idiopathic BPPV is most common between the ages of 50 and 70, although the condition is found in all age groups. The incidence of idiopathic BPPV ranges from 11 to 64 per 100,000 per year (Froehling 1991; Mizukoshi 1988). Sex distribution is about equal for post‐traumatic and post‐vestibular neuritis BPPV, although in its idiopathic form it appears to be approximately twice as common in females (Baloh 1987; Katsarkas 1978).

Aetiology

Balance is normally achieved by brain centres that monitor and synthesise information from the eyes, the vestibular system and position sensors in major joints. Angular acceleration (i.e. turning movements) is detected by the semicircular canals. There are three semicircular canals set in orthogonal planes (i.e. at 90 degrees to each other) in each ear (six semicircular canals in total: each ear providing reciprocal information) and they are therefore well placed to detect angular acceleration in any plane of head movement. The semicircular canals are filled with a fluid called endolymph. The main sense organ in each canal is called the crista: a collection of hair cells and nerve endings. The hairs of hair cells are embedded in a gelatinous matrix, the 'cupula'. Head rotation causes relative movement of the endolymph in the semicircular canal which bends the cupula and the embedded hairs of the crista, stimulating the relevant vestibular nerve.

The cause of benign positional vertigo is believed to be canalithiasis, principally affecting the posterior semicircular canal. Canalithiasis is characterised by the presence of free‐floating debris in the semicircular canal. Sudden change of position results in gravitational migration of the debris. Within the very thin lumen of the semicircular canal, this acts like a plunger, pulling endolymphatic fluid and bending the cupula: thus provoking vertigo.

An alternate theory, cupulolithiasis, asserts that canal debris becomes attached to the cupula, the specific gravity of which is normally the same as endolymph but with attached debris would become heavier, thus responding to any change in gravitational position of the head (rather than angular acceleration).

The latter theory has become less favoured, in part with the introduction of positioning techniques to treat BPPV. With free‐floating debris (canalithiasis), successively turning the head should continue to provoke nystagmus (repeated jerky movements of the eyes) in the same direction if the direction of rotation remains constant: the debris sinks to the most gravitationally dependent position of the canal each time. However, cupulolithiasis would predict a change in direction of the nystagmus as the head continues to turn. The heavy cupula under the influence of gravity should deviate in the opposite direction as the crista of the semicircular canal passes through the vertical plane. Clinical observation during positional manoeuvres confirms that when the direction of rotation is constant the direction of the nystagmus remains the same. The horizontal and anterior canals may also be affected by canalithiasis, although much less frequently.

Symptoms

Patients with posterior canal BPPV typically have episodic vertigo in association with a rapid change in head position, particularly movement relative to gravity and involving neck extension. The vertigo typically lasts for anything from a few seconds to one minute. Attacks may be associated with nausea, and the nausea may persist for much longer than the sensation of vertigo: sometimes for a few hours. Typical manoeuvres provoking vertigo include lying down in bed, extending the neck to reach up for objects on high shelves, bending over and sitting up from supine. A patient's balance is typically completely normal between episodes. Horizontal and anterior canal variants of BPPV are rare in comparison, and have subtly different patterns of presentation, which are beyond the scope of this discussion. In elderly patients, BPPV frequently coexists with other forms of dizziness and may present with falls and postural dizziness rather than classical vertigo (Lawson 2005).

Many cases of BPPV resolve spontaneously within a few weeks or months. Attacks tend to occur in clusters and symptoms may recur after an apparent period of remission. It is important to distinguish BPPV from central positional vertigo (which may occur with brainstem or cerebellar lesions including multiple sclerosis, ischaemia, degeneration and atrophy). Any transient or persisting positional nystagmus which does not conform to the classic features of BPPV should be considered to be central until otherwise excluded.

Diagnosis

The Dix‐Hallpike test (Hallpike manoeuvre) (Dix 1952), or the lateral head‐trunk tilt (Brandt 1999), are used to confirm the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV. A positive test provokes vertigo and nystagmus when a patient is rapidly moved from a sitting position to lying with the head tipped 45 degrees below the horizontal, 45 degrees to the side and with the side of the affected ear downwards. (Please see linked video demonstrating a positive Dix‐Hallpike test). This brings the posterior semicircular canal of the lower ear into vertical alignment. The nystagmus typically has a latency of a few seconds before onset and fatigues after approximately 30 to 40 seconds. The nystagmus is rotatory with the fast phase beating towards the lower ear (geotropic). The nystagmus adapts with repeated testing. Optic fixation (the eyes being able to fix on a specific object) may reduce the severity of the nystagmus and it is possible to test patients wearing Frenzel glasses (glasses with strong prisms for lenses, that remove the ability of the eyes to focus on an object). However, increasing the sensitivity of the Hallpike manoeuvre by wearing Frenzel glasses will reduce its specificity, since asymptomatic normal subjects can develop positional nystagmus on positional testing when optic fixation is removed. A proportion of patients with a typical history of posterior canal BPPV who have a negative Hallpike manoeuvre on the first occasion may demonstrate a positive test on retesting after a period of a few days, or have reproducible symptoms and paroxysmal nystagmus when tested with positional video‐oculography (Norre 1995). (Video‐oculography involves a special head‐mounted camera worn by the patient during positional movements. Any eye movements are objectively measured and recorded). There are no other specific investigations which can confirm or exclude the diagnosis of BPPV.

Description of the intervention

Treatment options

In many cases of BPPV spontaneous remission occurs before medical advice is sought and patients may simply seek an explanation for their symptoms without needing or demanding treatment. For more intrusive symptoms, there are a number of treatment options available. Vestibular suppressant medication (e.g. betahistine hydrochloride, prochlorperazine) is commonly prescribed, and may provide partial relief of prolonged nausea that some people experience after attacks. Medication does not prevent the symptoms of positional vertigo and does not alter the natural history of the condition. There is no role for regular and/or prolonged use of these medications and their use in the context of BPPV should be discouraged.

Brandt‐Daroff exercises (Brandt 1980) and canalith repositioning manoeuvres (Epley 1992; Semont 1988) are the main therapies for most patients who seek active treatment for their symptoms. They are purported to act by dispersion of the canal debris from the posterior semicircular canal into the vestibule, where it is inactive. These modalities of treatment all have a sequence of head and/or trunk positioning manoeuvres as a common factor.

In extreme circumstances, patients with frequent episodes of intractable vertigo showing no sign of spontaneous remission, and who have not responded to the Epley manoeuvre, may require or seek surgical treatment. This includes vestibular neurectomy where the singular nerve which selectively supplies the posterior semicircular canal is divided. Although the debris may continue to cause abnormal deflection of the cupula, the resulting sensory signal can no longer reach the brainstem for higher processing. In posterior semicircular canal obliteration surgery the posterior semicircular canal is exposed by drilling away part of the mastoid bone, and then packed firmly to obliterate the endolymphatic channel, thus also effectively removing the ability of the semicircular canal to produce aberrant sensory information.

The Epley manoeuvre

In recent years the Epley manoeuvre (Epley 1992) has become particularly popular. The technique involves a series of four movements of the head and body from sitting to lying, rolling over and back to sitting (Figure 1). (Please see linked video demonstrating how the Epley manoeuvre is performed). The Epley manoeuvre has been the subject of a previous Cochrane review (Hilton 2004) and significantly improves resolution of symptoms and signs of BPPV when compared to control or sham treatment.

1.

Reprinted from Otolaryngology ‐ Head and Neck Surgery, 107(3), Epley JM, The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, 399‐404, Copyright (1992), with permission from the American Academy of Otolaryngology ‐‐ Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, Inc.

Modifications of the Epley manoeuvre

The Epley technique can be and has been modified in clinical practice with the aim of improving patient outcome and hastening patient recovery. As well as variations on the 'classical' Epley manoeuvre, there are a number of additional treatment modalities that have been used in conjunction, including mastoid region oscillation, use of a multi‐axial positioning chair, maintaining an upright posture with limited cervical spine movement after the procedure, and concomitant vestibular rehabilitation exercises.

Mastoid region oscillation

Mastoid region oscillation (vibration), suggested by Epley, is a frequently described and criticised adjunct to treatment. During the repositioning manoeuvre, an electro‐mechanical device is worn on a headband which presses firmly on the skull and causes low‐frequency vibration (Epley 1992; Hain 2000; Li 1995). This is purported to shake the particles so they move out of the semicircular canal and back into the vestibule.

Multi‐axial positioning chair

More recently there has been added interest in a power‐driven, multi‐axial positioning chair combined with ongoing infrared video‐oculography, named Omniax®, which electronically monitors nystagmus while allowing the patient to be manoeuvred 360 degrees. Epley and Nakayama have proposed this advanced technology to be used in tertiary management for complicated cases (Nakayama 2005).

Post‐Epley postural restrictions

Remaining upright and limiting head movement for 24 to 48 hours is commonly advised for patients post‐treatment, with the aim of preventing the debris from going back into the semicircular canals. In order to achieve compliance and keep the head upright, a soft cervical collar has been advocated after the procedure is completed (Lynn 1995). This aims to prevent the reflux of the debris into the semicircular canal by limiting movement. An informal variation of the collar involves a soft towel, using the same principle of limiting movement during sleep. Other home instructions regarding head positioning include sleeping upright or semi‐reclined, usually for two to seven days.

Vestibular rehabilitation

Vestibular rehabilitation exercises have also been used to supplement the Epley manoeuvre in the treatment of BPPV (Chang 2008). These exercises are a group of interventions that aim to improve balance, vertigo symptoms and gaze instability. They include balance training, oculomotor exercises and functional activities.

Why it is important to do this review

There are now many variations of the Epley manoeuvre as it was originally described. There are no reviews which systematically address the potential benefit of any these modifications in clinical practice.

Objectives

To assess whether the various modifications of the Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for posterior canal BPPV enhance its efficacy in clinical practice.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Participants should be adults (age greater than 16 years) who have a clinical diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. The clinical diagnosis must state that the patient had a positive Dix‐Hallpike positional test with clear and classical features of positional nystagmus reflecting involvement of the posterior canal.

Types of interventions

The standard Epley manoeuvre versus comparison manoeuvre.

Comparison interventions sought included but were not limited to:

mastoid region oscillation;

vestibular rehabilitation exercises;

additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre;

post‐treatment instructions.

Comparisons sought were:

standard Epley manoeuvre versus a modification of the standard Epley manoeuvre; and

standard Epley manoeuvre versus standard Epley manoeuvre plus other invention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Persistence of vertigo attacks, assessed subjectively.

Proportion of patients improved by each intervention.

Conversion of a positive Dix‐Hallpike test to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test.

Secondary outcomes

Complications of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted systematic searches for randomised controlled trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions. The date of the search was 15 December 2011.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases from their inception for published, unpublished and ongoing trials: the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 4); PubMed; EMBASE; AMED; CINAHL; LILACS; KoreaMed; IndMed; PakMediNet; CAB Abstracts; Web of Science; BIOSIS Previews; ISRCTN; ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP; Google Scholar and Google.

We modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. Where appropriate, we combined subject strategies with adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by the Cochrane Collaboration for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2, Box 6.4.b. (Handbook 2011)). Search strategies for major databases including CENTRAL are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We scanned the reference lists of identified publications for additional trials and contacted trial authors where necessary. In addition, we searched PubMed, TRIPdatabase, NHS Evidence ‐ ENT & Audiology and Google to retrieve existing systematic reviews relevant to this systematic review, so that we could scan their reference lists for additional trials. We searched for conference abstracts using the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (MPH and WH) scanned the search results to identify trials that appeared broadly to address the subject of the review and scrutinised the full text of these articles for eligibility. Disagreement was resolved by the third author (EZ) or the Cochrane ENT Group editorial base.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (EZ, WH) independently extracted data from the studies using standardised data forms. Where data were missing from the trial reports, we contacted the study authors to request this information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All authors (MPH, WH, EZ) independently assessed the trials for risk of bias according to standard Cochrane methodology under six subject domains (Handbook 2011):

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding;

incomplete outcome data;

selective reporting;

other issues.

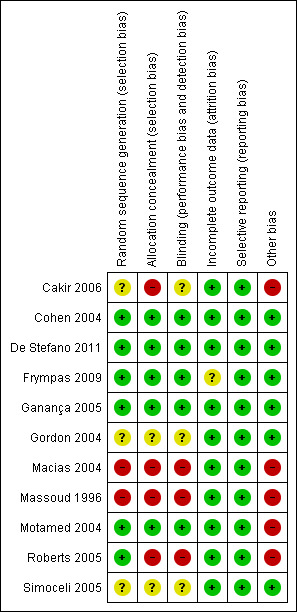

We presented our judgements for each study in 'Risk of bias' tables and a 'Risk of bias' summary figure (Figure 2).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Unit of analysis issues

There were no unit of analysis conflicts or difficulties.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We calculated statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2011)) to assess the comparability of included data. The I2 statistic describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (i.e. chance). An I2 greater than 50% is considered significant and under these circumstances it is unlikely that pooling data for meta‐analysis is appropriate.

Data synthesis

To analyse the data for this comparative effectiveness review we used Review Manager 5. We aimed to use intention‐to‐treat analysis as both arms of the included studies would have received an active intervention. If data from different studies were comparable and of sufficient quality then we combined them to give a summary measure of effect, otherwise data were not combined.

Data for our prespecified outcome measures were dichotomous. We calculated individual and pooled statistics as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We considered meta‐analysis in the absence of clinical or statistical heterogeneity.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We retrieved a total of 622 references from the searches run in August 2010 and December 2011: 323 of these were removed in first‐level screening (i.e. removal of duplicates and clearly irrelevant references), leaving 299 references for further consideration. We excluded 277 on the basis of the abstract. We sought to identify further trials from three review articles that we had identified (Devaiah 2010; Herdman 2000; Lempert 2005), however we found no further eligible studies from screening the references.

The methodological quality of the 22 identified studies from the first search was generally low and we excluded eight of the studies due to concern about a high probability of bias. We excluded another study (Chang 2008) because the outcome measures were not relevant to the review. Two studies were not included since one study referred to a trial that has since been abandoned (Palaniappan 2008) and one was in Korean and is still awaiting classification (Kim 2002). The source of the bias leading to the exclusion in the majority of trials was inadequate sequence generation and allocation concealment. There was no disagreement between the three authors about the inclusion/exclusion of studies.

Included studies

We included 11 studies in the review (Cakir 2006; Cohen 2004; De Stefano 2011; Frympas 2009; Ganança 2005; Gordon 2004; Macias 2004; Massoud 1996; Motamed 2004; Roberts 2005; Simoceli 2005). For a more extensive appraisal of the studies please see the Characteristics of included studies table. These 11 studies looked at different interventions. A total of nine studies used post‐Epley postural restrictions as their modification of the Epley manoeuvre (using a neck brace/head movement restrictions/instructions to sleep upright or propped up on pillows). Two studies assessed the effect of oscillation applied to the mastoid region during the Epley manoeuvre. One study that investigated the effect of post‐Epley postural restrictions also assessed the effect of adding additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre.

Post‐Epley manoeuvre postural restrictions

Nine studies included in the review assessed the benefit of post‐Epley manoeuvre postural restrictions (Cakir 2006; Cohen 2004; De Stefano 2011; Frympas 2009; Ganança 2005; Gordon 2004; Massoud 1996; Roberts 2005; Simoceli 2005).

Design

Four of the studies were assessor‐blinded (Cohen 2004; De Stefano 2011; Frympas 2009; Ganança 2005), in three the descriptions regarding blinding were unclear (Cakir 2006; Gordon 2004; Simoceli 2005) and in two there was no blinding (Massoud 1996; Roberts 2005). Additionally, the studies did lack 'sham' treatments, with no attempt made to blind the patients from their treatment group and thus the studies were at best single‐blinded.

Sample sizes

Sample sizes were small, ranging from 38 to 106 patients in total, with usable published data on a total of 528 patients.

Setting

The majority of the studies were based at large tertiary referral centres in large cities in the USA, Brazil, Greece, Turkey, Italy and Israel.

Participants

In all studies a clinical diagnosis of BPPV was based on clinical history and examination including a positive Dix‐Hallpike test.

Interventions

The periods of follow‐up were generally short, with most trials performing their follow‐up at one week, however two trials reported longer follow‐up periods of up to 20 months (Cakir 2006) and six months (Cohen 2004).

Outcomes

Five of the nine studies had a primary outcome measure of a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative alone (Cakir 2006; Frympas 2009; Ganança 2005; Roberts 2005; Simoceli 2005). De Stefano 2011 used a combination of Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative and the absence of nystagmus on infrared videoscopy. In comparison Massoud 1996 and Gordon 2004 combined the results of a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative with a subjective measure of improvement. The primary outcome measure was defined as patient assessment of the disappearance of the symptoms in Massoud 1996, and being completely free of signs and symptoms on examination in Gordon 2004, with both trials including a Dix‐Hallpike negative test within these measures. As these outcomes were reported together it does introduce a subjective element into what should be a purely objective measure, however no information of either of these outcome components as a single entity was available and thus we accepted comparing their results against those with a single outcome of Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative. For Cohen 2004, the outcome measures were vertigo intensity over time and odds of nystagmus over time, which meant the data provided in the report were not suitable for comparison with other trials in this review. On correspondence, the author provided the raw data including the outcome of a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative, as well as subjective vertigo rating. This enabled comparison of data and inclusion of the results.

Although Frympas 2009 and Ganança 2005 both assessed patients' subjective assessment of improvement of vertigo by means of an ordinal classification system, the categories themselves differed. Frympas 2009 defined the categories as no improvement, little improvement, great improvement and complete improvement, while Ganança 2005 defined the categories as asymptomatic, improved, no different or worse. For the purpose of this review, we combined both of the categories as follows: asymptomatic/complete improvement and all other categories were counted as no improvement/symptomatic. Patients who did not report on this measure were counted as no improvement/symptomatic (two patients in intervention and four in control in Frympas 2009).

Another additional outcome which was reported by two studies was post‐treatment vertigo intensity scale scores. These were measured by Cohen 2004 and Frympas 2009. For Frympas 2009 the vertigo intensity scale was rated from one (no dizziness) to 10 (unbearable dizziness) during the Dix‐Hallpike manoeuvre. For Cohen 2004 it was rated on a similar scale of 1 to 10 (1 (no vertigo) to 10 (extreme vertigo) during the Dix‐Hallpike manoeuvre). Roberts 2005 also reported on patients' subjective rating of vertigo from 0 to 10 (0 nothing, 10 greatest magnitude of vertigo). However, it was reported at three different positions during the Epley manoeuvre (rather than the Dix‐Hallpike manoeuvre). Thus we could compare the data to the Cohen 2004 and Frympas 2009 studies. Furthermore, we felt that because the Epley manoeuvres were performed before the postural restrictions, the assessment of vertigo intensity rating was not an adequate method for comparison between the groups and subsequently we did not report on those results.

Oscillation applied to the mastoid region during the Epley manoeuvre

Two studies assessed the effect of mastoid region oscillation during the Epley manoeuvre.

Design

One of the studies was assessor‐blinded (Motamed 2004) and the other was non‐blinded (Macias 2004). Again the studies lacked 'sham' treatments, with no attempt made to blind the patients from their treatment group.

Sample sizes

Sample sizes were 84 (Motamed 2004) and 102 patients (Macias 2004), with usable published data on a total of 186 patients.

Settings

The studies were based in tertiary referral centres in the UK and the USA.

Participants

Motamed 2004 included patients with traumatic head injury into the study (seven patients in the intervention group and four patients in the control group), whereas this was an exclusion criteria for the other studies discussed.

In both studies a clinical diagnosis of BPPV was based on clinical history and examination including a positive Dix‐Hallpike test.

Interventions

Motamed 2004 used a hand‐held body massager (Aquassager, Pollenex, East Windsor, NJ) and Macias 2004 used a Pollenex Aquassager (model K120, Holmes Corp., Sedalia, MO) in conjunction with the Epley manoeuvre in the intervention group. Follow‐up was much longer in both of these studies compared to the postural restrictions studies, with Macias 2004 reporting an average follow‐up of 9.44 months (ranging from to one week to 19 months) and Motamed 2004 reporting that follow‐up was at four to six weeks.

Outcomes

In the two studies the primary outcome measures varied but both reported on the number of patients that had a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative. In the case of Macias 2004 this was reported as the number of patients with a negative Dix‐Hallpike after one Epley manoeuvre. Based on this we calculated that patients that required more than one Epley manoeuvre were treatment failures. Motamed 2004 reported on a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative, but also the patients had to have been asymptomatic for the previous three weeks.

Augmentation of the Epley manoeuvre

Only one study (Cohen 2004) met the inclusion criteria for this outcome.

Design

Although the study was assessor‐blinded, there was no sham treatment involved.

Sample sizes

The sample size for this study arm was small, with the intervention group containing 24 patients and the control 26 (total 50 patients).

Setting

The study was conducted in the USA.

Participants

In this study a clinical diagnosis of BPPV was based on clinical history and examination including a positive Dix‐Hallpike test.

Interventions

The study included an intervention arm that assessed additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre. These additional steps followed directly after the standard Epley manoeuvre. It comprised the patient rolling 75° around the long axis of the trunk towards the unaffected side, then the head turning 45° towards the unaffected side and the patient's legs being lowered either side of the table and the torso brought upright while the head was held in position (45° towards the unaffected side). Follow‐up sessions were at one week after the tests and then at three and six months.

Outcomes

The Cohen 2004 study did not report on Dix‐Hallpike conversion rates, however on correspondence the author provided the raw data that allowed us to calculate the mean and standard deviation of a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative.

An additional outcome was measured using a post‐treatment vertigo intensity scale of 1 (no vertigo) to 10 (extreme vertigo).

Excluded studies

We excluded 10 studies from the review. Please refer to the Characteristics of excluded studies table for a detailed analysis of study exclusion. We excluded trials due to lack of randomisation or unclear randomisation allocation techniques, failure to blind outcome assessors, large losses to follow‐up, or due to the outcome measures differing from the outcome measures sought for the purposes of this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

Frympas 2009 used a computer‐generated minimisation technique described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies section. The assessing clinicians were blinded to the group allocation although three patients gave clues to their assessor as to which instructions they had been assigned. There is no information as to which group these patients belonged to and what effect this had on the outcome measure. The control group did not receive a sham procedure. Of the 64 patients, three were lost to follow‐up (two from the experimental group, one from the control group), having reported either personal reasons or the flu.

Ganança 2005 used a computer‐generated randomisation technique. The assessor was blind to group allocation. The control group did not receive a sham procedure. All 58 patients completed the trial and there was no selective outcome reporting.

Cakir 2006 was a randomised controlled trial, however the methodology was unclear regarding randomisation technique and blinding. We have contacted the authors for clarification but no response has been received. The control group did not receive a sham procedure. Of the 120 patients in the trial none were lost to follow‐up, however three patients were excluded from the study due to subconsciously performing postural restrictions. Another noteworthy point is that all the patients that required a third Epley manoeuvre in the control group were given postural restrictions, however these patients were not included in this review analysis. Additionally selection bias could be a possibility as they included patients with the symptoms of BPPV but without nystagmus, however as they were assessed separately, again these patients were not included in this review analysis. In total, 106 patients were included in this analysis from the trial (54 in intervention, 52 in control).

De Stefano 2011 used a computer‐generated randomisation technique. The assessor was blind to group allocation. The control group did not receive a sham procedure. All 38 patients completed the trial and there was no selective outcome reporting.

Gordon 2004 was a randomised controlled trial, however there was a lack of clarity regarding the randomisation and blinding methodology. We contacted the authors for clarification but no response has been received. The control group did not receive a sham procedure. Within a total of 125 patients and the groups relevant to this review there were no losses to follow‐up. There was no selective outcome reporting.

Simoceli 2005 was a randomised controlled trial, however it had an unclear randomisation and blinding methodology. We contacted the authors for clarification but no response has been received. The control group did not receive a sham procedure. There were no losses to follow‐up among the total sample of 50 patients. There was no selective outcome reporting.

Massoud 1996 used a sequential method for randomisation, allocating groups based on the day the patients were booked in for appointments (even days versus odd days of the week). This is a large source of potential bias for the study. There was no blinding in the study and this again is another large potential source of bias. The control group did not receive a sham manoeuvre. For the 96 patients in the study there were no losses to follow‐up. All groups were given instructions to avoid sudden head movements, however the intervention group were also asked to sleep upright for two days and then for the five remaining days not to sleep on the affected side. The control were asked to perform a limited number of postural restrictions therefore this may be a confounding factor. However, this topic is discussed a greater length in the Discussion.

Roberts 2005 used a random number table to allocate the random groups, however the authors intervened in the allocation to enable equivalence in certain parameters (such as gender, age, etc.), which resembles the minimisation technique. A potential source of bias was that some patients were excluded from the study even though they were willing to partake, to "avoid compromising the equivalence of the two groups". The trial was non‐blinded. The control group did not receive a sham manoeuvre. There were no losses to follow‐up within the total sample of 42 patients. Additionally all patients, if they had a positive Dix‐Hallpike at one‐week follow‐up, were provided with instructions for post‐manoeuvre restrictions, regardless of group. For the purpose of this review, we included the results from the one‐week follow‐up in the analysis to prevent confounding.

Cohen 2004 used a random number table to generate the groups' random allocation, which the author clarified on contact. The study was single‐blinded. The control group did not receive a sham manoeuvre. There were no losses to follow‐up among the 76 patients. There did not appear to be selective outcome reporting.

Motamed 2004 used a sealed envelope technique for the sequence generation. The study was single‐blinded. The control group did not receive a sham manoeuvre. There were a total of 84 patients of which five were lost to follow‐up. This is considered reasonable and does not confer a risk of bias. Both the control and the intervention groups had postural restrictions which were to avoid rapid head movements, head‐down positions and to sleep at 45 degrees for two days. Although this study was assessing the effect of oscillation to the mastoid region, this could confound the data. This is further examined in the Discussion section.

Macias 2004 used a coin flip as an allocation method for the randomisation process. We perceived this as a high potential source of bias for this review. There was no blinding in this study. The control group did not receive a sham manoeuvre. Of the 102 patients there were none lost to follow‐up. All patients were advised to avoid lying flat for two days. Although this study was assessing the effect of oscillation to the mastoid region, this could confound the data. This is further examined in the Discussion section.

A summary of the review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study is shown in Figure 2.

Effects of interventions

The 11 included trials comprised of a total of 855 patients. Complete data were available for 847 patients (three patients were lost to follow‐up in the Frympas 2009 study and five were lost to follow‐up in the Motamed 2004 study).

Postural restrictions following an Epley manoeuvre

Persistence of vertigo attacks, assessed subjectively

Frympas 2009 presented data for subjective intensity of vertigo during the Dix‐Hallpike test. The mean score was lower in the experimental group, but the difference in the measures was not statistically significant between groups. On correspondence with the author, the data were reported as not normally distributed (i.e. non‐parametric) and thus have not been pooled with other data, however the data have been reported in the other data types section (Analysis 1.4). Cohen 2004 presented the data for subjective intensity rating of vertigo by patients during the Dix‐Hallpike test. Similar to Frympas 2009 the mean score was lower in the experimental group and also the difference in the measures was not statistically significant between groups (Analysis 1.3). Prior to being entered into the RevMan 5 software for analysis, we checked the data for normality using the D'Agostino‐Pearson normality omnibus test (Prism (Graphpad)), which confirmed normal distribution.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Post‐Epley postural restrictions, Outcome 4 Post‐treatment vertigo intensity (1 to 10 scale) ‐ non‐parametric data.

| Post‐treatment vertigo intensity (1 to 10 scale) ‐ non‐parametric data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Experimental | Control | ||||

| Frympas 2009 | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total |

| Frympas 2009 | 1.90 | 1.94 | 29 | 2.86 | 2.80 | 30 |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Post‐Epley postural restrictions, Outcome 3 Post‐treatment vertigo intensity (1 to 10 scale).

Proportion of patients improved by each intervention

The trials Frympas 2009 and Ganança 2005 reported categorical data for symptom improvement which we synthesised to give a dichotomous outcome of 'complete resolution' versus 'partial resolution or no improvement'. The combined data from both trials showed no significant difference between the control group and the postural restriction group (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Post‐Epley postural restrictions, Outcome 2 Subjective patients' assessment of improvement.

Conversion of a positive Dix‐Hallpike test to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test

Frympas 2009 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test within seven days after the Epley manoeuvre. The study reported a greater success rate of conversion to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test in the intervention group, with 27/30 in the experimental group (90.0%) and 23/31 in the control group (74.2%) having a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

Ganança 2005 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test seven days after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 23/28 patients (82.1%) and in the control group 22/30 (73.3%) showed a negative conversion. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

Cakir 2006 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test five days after the Epley manoeuvre. All of the 54 patients in the intervention group (100%) and 46/52 in the control group (88.4%) showed a negative conversion. There was a significant difference between the number of Dix‐Hallpike conversions from positive to negative in the control group compared to the intervention, favouring the intervention (risk ratio (RR) 1.13, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 1.25, P = 0.02).

De Stefano 2011 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test seven days after the Epley manoeuvre in conjunction with infrared videoscopy. In the intervention group 15/18 (83.3%) and 19/20 in the control (95%) showed no signs of recurrence. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

Simoceli 2005 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test between two to four days after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 18/23 (78.3%) and 17/27 in the control (63.0%) showed a negative conversion. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

Roberts 2005 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test seven days after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 20/21 (95.2%) and 19/21 in the control (90.5%) showed a negative conversion. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

Massoud 1996 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test seven days after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 21/23 (91.3%) and 22/23 in the control (95.6%) showed a negative conversion. This was the only trial on the effect of postural restrictions which reported more Dix‐Hallpike conversions from positive to negative in the control group compared to the intervention. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

Gordon 2004 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test seven days after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 21/25 (84.0%) and 40/50 in the control (80.0%) showed a negative conversion. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

Cohen 2004 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test seven days after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 21/26 (80.8%) and in the control 11/26 (42.3%) showed a negative conversion. This was the second trial included in the review which reported a significant difference between the number of Dix‐Hallpike conversions from positive to negative in the control group compared to the intervention, favouring the intervention group (RR 1.91, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.11, P = 0.009).

The overall pooled result for conversion of a positive Dix‐Hallpike test to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test

The combined data from nine trials and 528 patients showed a highly significant difference between the control and the intervention groups, with the intervention (post‐Epley postural restrictions) being more effective than control (Epley alone) (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.22, P = 0.002) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Post‐Epley postural restrictions, Outcome 1 Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Post‐Epley postural restrictions, outcome: 1.1 Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative.

Complications of treatment

Four of the nine studies reported on the adverse effects that patients suffered. Frympas 2009 noted that two patients in the intervention group and one patient in the control group suffered neck stiffness. Additionally, two patients in the control group developed horizontal BPPV. Roberts 2005 also had two patients that suffered horizontal BPPV at follow‐up, however these were in the intervention group. The authors postulated that one patient had horizontal BPPV at initial presentation which was masked by the severity of posterior canal nystagmus, while the other patient had developed horizontal canal migration of otoconia due to lifting his head during the Epley manoeuvre. Gordon 2004 reported that 70% of all patients had transient nausea and 35% reported disequilibrium after the Epley manoeuvre regardless of group allocations, and additionally 40% of all patients in the intervention group complained of discomfort due to wearing the neck collar. De Stefano 2011 recorded that 5/18 (27.8%) of patients in the postural restrictions group reported neck stiffness compared to none in the control group.

Mastoid region oscillation during the Epley manoeuvre

Persistence of vertigo attacks, assessed subjectively

No studies applying this intervention reported on this outcome.

Proportion of patients improved by each intervention

No studies applying this intervention reported on this outcome.

Conversion of a positive Dix‐Hallpike test to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test

Macias 2004 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test between one week and 19 months after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 36/39 (92.3%) and in the control 59/63 (93.7%) showed a negative conversion. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

Motamed 2004 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test between four weeks and six weeks after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 28/42 (66.7%) and in the control 26/42 (61.9%) showed a negative conversion. There was no statistical difference between the groups.

The overall pooled result for conversion of a positive Dix‐Hallpike test to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test

The combined data from two trials and 186 patients did not show a significant difference between the control and the intervention groups (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Mastoid region oscillation, Outcome 1 Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative.

Complications of treatment

No studies measuring this intervention reported on this outcome.

Augmentation of the Epley manoeuvre

Persistence of vertigo attacks, assessed subjectively

Cohen 2004 provided the raw data on request for subjective intensity rating of vertigo by patients during the Dix‐Hallpike test. The mean score was lower in the intervention group but the difference in the measures was not statistically significant between groups. Prior to being entered into the RevMan 5 software for analysis, we checked the data for normality using the D'Agostino‐Pearson normality omnibus test, which confirmed normal distribution (Analysis 3.2)

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Augmented Epley, Outcome 2 Post‐treatment vertigo intensity (1 to 10 scale).

Proportion of patients improved by each intervention

No studies measuring this intervention reported on this outcome.

Conversion of a positive Dix‐Hallpike test to a negative Dix‐Hallpike test

Cohen 2004 performed the Dix‐Hallpike test seven days after the Epley manoeuvre. In the intervention group 16/24 (66.7%) and in the control 11/26 (42.3%) had a Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative. There was no statistical difference between the groups (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Augmented Epley, Outcome 1 Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative.

Complications of treatment

No studies applying this intervention reported any complications.

Other interventions sought

We found no studies of adequate methodological quality that investigated other interventions such as vestibular rehabilitation exercises or post‐treatment instructions. A high‐powered trial (Chang 2008) did investigate vestibular rehabilitation exercises, however the primary outcomes of the study were not those sought for this review.

Discussion

The 21 studies identified by the first search as being trials using modifications of the Epley manoeuvre versus a control in adult posterior canal benign paroxsymal positional vertigo (BPPV) were generally of low methodological quality, particularly in the areas of allocation concealment and blinding of the outcome assessors. Conversion from a positive to negative Dix‐Hallpike test is the only objective marker of any physiological change resulting from treatment and we therefore selected this as the primary outcome measure. Subjective assessment of vertigo by patients was the principal patient‐orientated outcome.

We included 11 studies in the review with a total of 855 patients (Cakir 2006; Cohen 2004; De Stefano 2011; Frympas 2009; Ganança 2005; Gordon 2004; Macias 2004; Massoud 1996; Motamed 2004; Roberts 2005; Simoceli 2005). These addressed three modifications of the Epley manoeuvre: postural restrictions after the Epley manoeuvre, mastoid region oscillation during the Epley manoeuvre and additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre (augmentation of the Epley manoeuvre).

Postural restrictions following an Epley manoeuvre

Nine studies (Cakir 2006; Cohen 2004; De Stefano 2011; Frympas 2009; Ganança 2005; Gordon 2004; Massoud 1996; Roberts 2005; Simoceli 2005) compared the use of postural restrictions in conjunction with the Epley manoeuvre to the Epley manoeuvre alone as a control. Individually, seven of these nine studies did not show a significant difference between groups for either primary or secondary outcome measures. It is noteworthy that two of these studies (Gordon 2004; Massoud 1996) reported on a Dix‐Hallpike negative test combined with a subjective assessment of improvement as an outcome measure. De Stefano 2011 used a combined measure of negative Dix‐Hallpike as well as absence of nystagmus on infrared videoscopy. The data from Cakir 2006 demonstrated a significant difference between the number of Dix‐Hallpike conversions from positive to negative in the control group compared to the intervention. This denoted that the intervention was significantly more efficacious than control (risk ratio (RR) 1.13, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 1.25, P = 0.02). Analysis of the raw data obtained from the author of Cohen 2004 revealed significant differences between the intervention and control based on Dix‐Hallpike test conversion from positive to negative, indicating that postural restrictions in conjunction with the Epley manoeuvre were significantly more effective than control (RR 1.91, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.11, P = 0.009). Overall, considering the primary outcome measure of Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative, when we combined the data from nine studies there was a highly significant difference (P = 0.002). This indicates that postural restrictions in conjunction with the Epley manoeuvre are significantly more effective than the Epley manoeuvre alone (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.22) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 3). It is, however, important to note that this statistically significant effect only highlights a small improvement in treatment efficacy. An Epley manoeuvre alone is effective in just under 80% of patients within this patient group. The additional intervention of postural restrictions has a number needed to treat (NNT) of 10.

In terms of secondary outcomes the combined data were non‐significant. Two studies (Frympas 2009; Ganança 2005) evaluated the proportion of patients improved by each intervention. The combined data from both trials showed no significant difference between the control group and the postural restriction group (Analysis 1.2). Cohen 2004 assessed the persistence of vertigo attacks using a subjective post‐treatment vertigo intensity rating. Although the mean score was lower in the experimental group, the difference in the measures was not statistically significant between groups (Analysis 1.3). Frympas 2009 also assessed subjective vertigo intensity ratings and found no statistical difference between control and intervention. As the data were non‐parametric, it is not possible to pool the data from this study with the Cohen 2004 study. The vertigo intensity ratings also differed in their scales, with Cohen 2004 using a scale from 1 (no intensity) to 10 (severe intensity), and Frympas 2009 using a scale from 0 (no intensity) to 10 (severe intensity). Future studies would benefit from a validated scale that could be used to compare and combine data.

In regard to complications of treatment, three of the nine studies reported on the adverse effects that patients suffered from. Frympas 2009 noted that two patients in the intervention group (postural restrictions) and one patient in the control group suffered with neck stiffness. Additionally, two patients in the control group were diagnosed with horizontal BPPV at follow‐up. Roberts 2005 also had two patients that suffered horizontal BPPV at follow‐up, however these were in the postural restriction group. Gordon 2004 reported that 70% of all patients had transient nausea and 35% reported disequilibrium after the Epley manoeuvre regardless of group allocations; in addition to this 40% of all patients in the intervention group complained of discomfort due to wearing a neck collar.

It is noteworthy that many of the studies looking at postural restrictions differed in their methodology. In regard to randomisation, Frympas 2009 and Roberts 2005 used a minimisation technique, equally distributing pre‐selected prognostic factors such as age and gender between study arms. This has been accepted as an effective means of allocation when the sample size is small and other randomisation techniques might cause skewed variables. (See Characteristics of included studies for a more detailed description of the technique). While most studies only performed the Epley manoeuvre once, Massoud 1996, Cohen 2004 and Cakir 2006 repeated the manoeuvre on two or more occasions. For the purpose of this review, where possible, we used results from the first attempt. Cakir 2006 repeated the Epley manoeuvre in patients that did not improve and reported these separately. Massoud 1996 repeated the Epley manoeuvre and same instructions (either postural restrictions or no instructions) on patients with a positive Dix‐Hallpike test at one‐week follow‐up, re‐evaluating them at two weeks post‐initial treatment. We combined the results, giving an overall success rate, regardless of the number of treatments the patients had received. Cohen 2004, however, performed three Epley manoeuvres with every patient, with a maximum of a five‐minute 'inter‐trial' interval. This may confound the results, where high success was reported, although the results still significantly favour the postural restrictions group compared to control. The authors provided the raw data from the trial, where follow‐up was performed at one week, three months and six months. At each follow‐up the sample size reduced significantly and the only follow‐up which contained the complete initial sample was the first; these are the data we included in the analysis.

The postural advice in most studies generally consisted of two different instructions. First, avoiding lying on the affected ear (for a period of one to five days) and secondly to sleep upright (for 24/48 hours). One study considered one other measure in isolation compared to the others: this was advice not to engage in sport in De Stefano 2011. Instructions regarding sudden head movement were more variable. Some studies advised restricted sudden head movement as part of the postural restrictions (Frympas 2009; Massoud 1996; Simoceli 2005). In Massoud 1996, control and intervention group patients were all instructed to restrict sudden head movements and the experimental intervention was confined to sleeping upright and not lying flat for 48 hours. Our search did not identify any trials which compared the length of postural restrictions as a comparison intervention. Although there is methodological heterogeneity in the precise detail of postural restriction between trials, the direction of effect is comparable and combining data for meta‐analysis is considered reasonable.

Oscillation applied to the mastoid region during the Epley manoeuvre

Two studies (Macias 2004; Motamed 2004) compared the use of mastoid region oscillators during the Epley manoeuvre to the Epley manoeuvre alone as a control. Motamed 2004 used a hand‐held body massager (Aquassager, Pollenex, East Windsor, NJ) and Macias 2004 used a Pollenex Aquassager (model K120, Holmes Corp., Sedalia, MO). Individually these studies did not show a significant difference between groups for either primary or secondary outcome measures. When we combined the study data there was no statistically significant difference (Analysis 2.1). Complication rates were not reported by the studies. All patients in these studies were given advice about postural restriction. The results from the pooled trial data of postural restrictions have shown significant benefit. There are no trial data which independently address the issue of mastoid region oscillation in patients who have not received postural restrictions, but there is no physiological reason to suggest why the effects should be synergistic. Motamed 2004 was the only study in this review that included patients with a history of head trauma (seven patients in the intervention group and four patients in the control group). This represents a slightly different study population but there is no evidence to date which demonstrates a different efficacy of treatment for BPPV dependent on aetiology in any other context. Both studies evaluating the use of oscillators had very long follow‐up periods (four to six weeks in Motamed 2004 and up to 19 months in Massoud 1996) and it is possible that during this time the pathology may have resolved itself.

Additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre

One study (Cohen 2004) had an intervention arm evaluating the use of additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre compared to the Epley manoeuvre alone as a control. This study did not show any statistically significant difference on either primary or secondary measures (Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative and vertigo intensity rating). Complications of treatment were not reported.

Further considerations

Frenzel lenses were used by Frympas 2009, Ganança 2005, Gordon 2004 and Cakir 2006, in comparison to Roberts 2005 who used Synapsys video goggles, Cohen 2004 who used electrooculography, and De Stefano 2011 who used infrared videoscopy in addition to the Dix‐Hallpike test to assess the presence of nystagmus. Massoud 1996, Simoceli 2005, Motamed 2004 and Macias 2004 relied on clinical assessment to determine the severity and direction of nystagmus at diagnosis and assessment. Clinical assessment could have introduced assessor error, especially when concerning patients with a mixed picture or high severity of BPPV.

Conclusion

In conclusion the findings of the review are based on 11 relatively small trials focusing on postural restrictions, mastoid region oscillation and additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre. Some of the studies included were at a high risk of potential bias (see Figure 2). Further research should focus on a robust strategy for randomisation and allocation concealment with a sham manoeuvre in the control group, and examine the range of possible modifications which are currently applied in contemporary clinical practice.

There is evidence to suggest that post‐Epley postural restrictions are more effective than the Epley manoeuvre alone in terms of the Dix‐Hallpike responses in BPPV, although the effect size is small, with a NNT of 10. There is insufficient evidence to either recommend or refute the benefit of associated mastoid region oscillation or additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre for BPPV. Further trials are warranted.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is evidence supporting a statistically significant effect of post‐Epley postural restrictions in comparison to Epley manoeuvre alone. However, it is important to note that this statistically significant effect only highlights a small improvement in treatment efficacy. An Epley manoeuvre alone is effective in just under 80% of patients with typical benign paroxsymal positional vertigo (BPPV). The additional intervention of postural restrictions has a number needed to treat (NNT) of 10. The addition of postural restrictions does not expose the majority of patients to risk of harm, does not pose a major inconvenience, and can be routinely discussed and advised. Specific patients who experience discomfort due to wearing a cervical collar and inconvenience in sleeping upright may be treated with Epley manoeuvre alone and still expect to be cured in most instances.

There was no evidence of a difference between oscillation to the mastoid region during the Epley manoeuvre and the additional steps in the Epley manoeuvre as currently applied in routine clinical practice.

Implications for research.

Further research in this field should comply with the following criteria if possible. Trials should:

be pre‐registered;

be reported in line with the recommendations outlined in the CONSORT statement 2010 (CONSORT 2010);

use a rigorous randomisation technique with a particular emphasis on allocation concealment;

blind the outcome assessors;

use a post‐treatment Dix‐Hallpike test as part of the reported results; and

include longer‐term follow‐up of patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following for providing additional information regarding their studies: André AP, Cohen HS, De Stefano A, Frympas G, Ganança FF, Macias JD, Massoud E, Motamed M, Roberts RA.

We are grateful to both Jenny Bellorini and Martin Burton from the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group for their extensive advice and support throughout the development of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| CENTRAL | Cochrane ENT Trials Register | PubMed | EMBASE (Ovid) |

| #1 VERTIGO single term (MeSH) #2 DIZZINESS single term (MeSH) #3 vertig* OR dizziness OR paroxysmal OR BPPV #4 #1 OR #2 OR #3 #5 PHYSICAL THERAPY MODALITIES explode all trees (MeSH) #6 HEAD MOVEMENTS single term (MeSH) #7 (epley* OR semont* OR canalith* OR otolith* OR particle) AND (position* OR reposition* OR maneuver* OR manoeuvr*) #8 #5 OR #6 OR #7 #9 #4 AND #8 | ((Vertig* OR bppv OR paroxysmal OR dizziness) AND (Epley* OR semont* OR canalith* OR otolith* OR particle) AND (position* OR reposition* OR maneuvr* OR manoeuvr*))) | #1 “VERTIGO” [Mesh] OR vertig* [tiab] OR dizziness [tiab] OR paroxysmal [tiab] OR BPPV [tiab] #2 "Dizziness"[Mesh:NoExp] #3 “PHYSICAL THERAPY MODALITIES” [Mesh] OR “HEAD MOVEMENTS” [Mesh:NoExp] OR ((epley* [tiab] OR semont* [tiab] OR canalith* [tiab] OR otolith* [tiab] OR particle [tiab]) AND (position* [tiab] OR reposition* [tiab] OR maneuver* [tiab] OR manoeuvr* [tiab])) #4 (#1 OR #2) AND #3 | 1 vertigo/ or *dizziness/ 2 (vertig* or dizziness or paroxysmal or BPPV).tw. 3 exp physiotherapy 4 ((Epley* or semont* or canalith* or otolith* or particle) and (position* or reposition* or maneuvr* or manoeuvr*)).tw. 5 1 or 2 6 3 or 4 7 5 AND 6 |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | Web of Science | BIOSIS Previews (Web of Knowledge) | ISRCTN (mRCT) |

| S1 (MH "Vertigo"# OR #MM "Dizziness"#) S2 TX Vertigo* OR bppv OR paroxysmal OR dizziness S3 S1 or S2 S4 (MH "Physical Therapy+") S5 TX ((Epley* OR semont* OR canalith* OR otolith* OR particle) AND (position* OR reposition* OR maneuvr* OR manoeuvr*)) S6 S4 or S5 S7 S3 and S6 | TS=((Vertigo* OR bppv OR paroxysmal OR dizziness) AND ((Epley* OR semont* OR canalith* OR otolith* OR particle) AND (position* OR reposition* OR maneuvr* OR manoeuvr*))) | TS=((Vertigo* OR bppv OR paroxysmal OR dizziness) AND ((Epley* OR semont* OR canalith* OR otolith* OR particle) AND (position* OR reposition* OR maneuvr* OR manoeuvr*))) | Epley OR semont OR canalith OR otolith particle AND (vertigo OR bppv) |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Post‐Epley postural restrictions.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative | 9 | 528 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [1.05, 1.22] |

| 2 Subjective patients' assessment of improvement | 2 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.87, 1.85] |

| 3 Post‐treatment vertigo intensity (1 to 10 scale) | 1 | 52 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.96 [‐2.04, 0.12] |

| 4 Post‐treatment vertigo intensity (1 to 10 scale) ‐ non‐parametric data | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 2. Mastoid region oscillation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative | 2 | 186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.89, 1.17] |

Comparison 3. Augmented Epley.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Dix‐Hallpike conversion from positive to negative | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.93, 2.68] |

| 2 Post‐treatment vertigo intensity (1 to 10 scale) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.81 [‐1.84, 0.22] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cakir 2006.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (non‐blinded) | |

| Participants | 120 patients in total (66 female, 54 male). The control group's mean age was 48 years (range 24 to 82), the intervention group had a mean age of 49 (range 23 to 78) The initial assessment was at 5 days, with follow‐up period ranging from 6 to 20 months 3 patients in the control group were found to be subconsciously performing postural restrictions and were excluded from the study analysis The mean duration of the symptoms of vertigo was 30.1 days (range 1 to 200) in the control group and 28.4 days (range 1 to 300) in the intervention group The inclusion criteria were a positive Dix‐Hallpike test assessed using Frenzel glasses and symptoms of vertigo. Patients with unilateral, bilateral posterior canal BPPV and posterolateral BPPV were included. 8 patients in total had BPPV without nystagmus and were followed up in a separate group. There is no information regarding exclusion criteria |

|

| Interventions | All patients had the standard single Epley manoeuvre performed without premedication The control group had no other instructions or intervention, and were encouraged to perform all kinds of movements The experimental group had post‐manoeuvre instructions to wear a cervical collar for 48 hours, to use 2 to 3 pillows at night for 48 hours and to refrain from turning to the affected ear |

|

| Outcomes | PRIMARY OUTCOMES: Objective: Dix‐Hallpike negative |

|

| Notes | Patients in the control group who on questioning had subconsciously refrained from turning to the affected side during sleep, performed head elevation, avoided sudden head movements or refrained from normal daily activities were excluded (n = 3) All the patients that needed a third Epley manoeuvre in the control group were prescribed postural restrictions (n = 6). This could confound the data 8 patients with vertigo symptoms, but without nystagmus were included in the trial; 3 in the intervention group and 5 in the control ‐ this could introduce the possibility of selection bias |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear (the authors have been contacted) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Unclear (the authors have been contacted) 8 patients with vertigo symptoms, but without nystagmus were included in the trial; 3 in the intervention group and 5 in the control ‐ this could introduce the possibility of selection bias. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear (the authors have been contacted) ‐ assumed non‐blinded as not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No patients were lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | High risk | All the patients that needed a third Epley manoeuvre in the control group were prescribed postural restrictions (n = 6); this could confound the data Additionally no information was provided regarding exclusion criteria |

Cohen 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (single‐blinded) | |

| Participants | 76 patients in total (53 female, 23 male). The mean age was 56 years. The patients were followed up at 1 week after the tests and then at 3 and 6 months The median duration of BPPV symptoms was 3 months and every patient had to have had a history of vertigo for 1 week or more The inclusion criteria were a positive Dix‐Hallpike test and positive eye movement on electroculography Exclusion criteria were any limitations of cervical spine movement and any significant neurological, orthopaedic or otological diseases |

|

| Interventions | The groups were randomly assigned to 3 groups via use of a random number table; the standard Epley manoeuvre (control), the augmented Epley manoeuvre and the postural restriction group All patients received 3 consecutive Epley manoeuvres with a maximum of a 5‐minute interval The control group had no other instructions or intervention The patients in the postural restriction group received a standard Epley manoeuvre and then home instructions to avoid sleeping on the affected side, to sleep with extra pillows, to wrap a towel around the neck at night and to keep the head upright while asleep. The duration of these restrictions is unclear. The augmented Epley included the steps from the standard Epley manoeuvre but also had additional steps. These immediately followed the standard steps and included the patient's trunk rolling 75° in the vertical axis towards the unaffected side, then the head turning 45° towards the unaffected side and the patient's legs being lowered either side of the table and the torso brought upright while the head was held in position (45° towards the unaffected side) Follow‐up was performed at 1 week, 3 months and 6 months post‐treatment Additionally subjective tests were performed in order to ascertain the extent of the vertigo. These used a 10‐point visual analogue scale to measure the severity of vertigo. Balance was also assessed using computerised dynamic posturography. |

|

| Outcomes | PRIMARY OUTCOMES: Objective: Dix‐Hallpike negative Odds of nystagmus over time Subjective: Vertigo intensity over time, including vertigo intensity after the Dix‐Hallpike test. Rated on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 (no vertigo) to 10 (extreme vertigo) Vertigo frequency over time. Rated on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 (no vertigo) to 10 (constant vertigo). Balance was assessed over time using computerised dynamic posturography |

|

| Notes | Raw data from the trial was provided by the author including Dix‐Hallpike results and vertigo intensity scores, allowing inclusion and comparison of the results in this review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random number table (contact with lead author) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Blinded assessors for each group |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Single‐blinded (assessors) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No incomplete data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

De Stefano 2011.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (single‐blinded) | |