Abstract

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) shows treatment benefits among individuals with pain interference; however, effects of Internet-delivered CBT-I for this population are unknown. This secondary analysis used randomized clinical trial data from adults assigned to Internet-delivered CBT-I to compare changes in sleep by pre-intervention pain interference. Participants (N=151) completed the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and sleep diaries (sleep onset latency [SOL]; wake after sleep onset [WASO]) at baseline, post-assessment, six- and twelve-month follow-ups. Linear mixed-effects models showed no differences between pain interference groups (no, some, moderate/severe) for changes from baseline to any follow-up timepoint for ISI (p=.72) or WASO (p=.88). There was a small difference in SOL between those reporting some vs. no or moderate/severe pain interference (p=.04). Predominantly comparable and sustained treatment benefits for both those with and without pain interference suggest that Internet-delivered CBT-I is promising for delivering accessible care to individuals with comorbid pain and insomnia.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Internet, Insomnia, Pain Interference

Insomnia is commonly comorbid with daytime pain interference. Approximately 67 to 88 percent of people with chronic pain endorse sleep complaints (Morin, LeBlanc, Daley, Gregoire, & Mérette, 2006; Smith & Haythornthwaite, 2004). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is the first-line treatment for insomnia (Schutte-Rodin, Broch, Buysse, Dorsey, & Sateia, 2008). Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that stand-alone CBT-I (Pigeon et al., 2012; Tang, Goodchild, & Salkovskis, 2012; Vitiello et al., 2013), as well as hybrid CBT interventions integrating CBT-I and CBT for pain management (Currie, Wilson, Pontefract, & deLaplante, 2000; Edinger, Wohlgemuth, Krystal, & Rice, 2005; Jungquist et al., 2010; Martínez et al., 2014; Miró et al., 2011; Pigeon et al., 2012; Sánchez et al., 2012; Vitiello, Rybarczyk, Korff, & Stepanski, 2009), improve sleep among individuals with pain. However, these studies have tested CBT-I using face-to-face treatment. Moreover, only one study (Vitiello et al., 2009) examined the long-term maintenance of patients’ treatment gains out to a year post-treatment; none examined whether maintenance differed among participants by their level of pain interference. While studies support that CBT-I delivered face-to-face by a trained therapist effectively attenuates insomnia among individuals with pain interference (Koffel, Koffel, & Gehrman, 2015; Tang, 2009), it is not yet known whether these individuals may benefit from a fully automated, self-guided Internet-delivered CBT-I treatment.

Internet-delivered CBT-I has been shown to effectively treat insomnia in the general population (Ritterband et al., 2017), and does so in a highly-accessible, low-cost, and standardized format that may be especially beneficial to individuals with co-occurring disabling symptoms such as pain. Authors have previously demonstrated the benefits of Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi), a fully-automated, self-guided Internet-delivered CBT-I program. In the primary trial, participants receiving SHUTi, compared to those in an Internet-delivered sleep education condition, showed significantly reduced insomnia severity, sleep onset latency, and wake after sleep onset, effects that were maintained through one-year follow-up (Ritterband et al., 2017). It is not yet known, however, whether level of pain interference prior to starting an Internet-delivered CBT-I program such as SHUTi may moderate treatment benefits. It might be assumed that Internet-delivered CBT-I that includes all the same active treatment components of face-to-face CBT-I would be beneficial to people with comorbid pain interference, as these components have demonstrated efficacy among individuals with chronic pain in prior trials (Currie et al., 2000; Edinger et al., 2005; Jungquist et al., 2010; Martínez et al., 2014; Miró et al., 2011; Pigeon et al., 2012; Sánchez et al., 2012; Vitiello et al., 2009). However, if individuals with comorbid insomnia and pain interference report worse sleep outcomes relative to those with insomnia but no pain, it would suggest that treatment modifications (e.g., pain-tailored content or human clinical support) may be warranted.

To address the question regarding whether level of preexisting pain interference modifies treatment efficacy of Internet-delivered CBT-I, this secondary data analysis examines whether pre-treatment pain interference is related to treatment benefits reported by participants randomized to SHUTi (active treatment arm) in a national (U.S.) RCT. For the primary objective of this secondary analysis, the extent to which participants’ sleep outcomes changed as a result of receiving Internet-based CBT-I was compared across participants categorized at pre-treatment by no, some, or moderate/severe pain interference.

METHOD

Participants, Procedure, and Program

This is a secondary data analysis of a national (U.S.) RCT. The purpose of the primary trial was to evaluate the efficacy of SHUTi (Ritterband et al., 2017), an Internet-delivered CBT-I program, compared to Internet-delivered patient education. For the present manuscript, only data from Internet CBT-I intervention participants (i.e., SHUTi condition) are analyzed. Data evaluating differences in response to SHUTi by pain interference has not been previously published.

Methodological details for the RCT (including further details on participants, design, and study procedures and the full CONSORT diagram) have been previously reported (Ritterband et al., 2017); key aspects are reviewed here. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Virginia. Participants were recruited from across the U.S. via a study website from October 2011 through July 2013 (ClinicalTrials.gov registration NCT01438697). Comorbid medical conditions were included unless they were deemed active, unstable, and degenerative (e.g., congestive heart failure or multiple sclerosis) in a manner that could worsen the insomnia. Chronic pain was neither an inclusion nor exclusion criterion. Participants could be taking medications, including for pain or sleep, if the medication regimen had not been changed in the previous 3 months. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to starting study procedures. Participants in the CBT-I group received access to SHUTi for nine weeks. SHUTi consists of six intervention Cores that act as an online equivalent to the weekly sessions typically conducted in face-to-face CBT-I (Morin, 1993). The program is entirely automated and self-guided; technical support was available, but no clinical direction was provided. For a more detailed description of SHUTi, see Thorndike et al., 2008. Participants completed online assessments at baseline prior to randomization (pre-assessment), after the intervention period (i.e., nine weeks from baseline; post-assessment), and at six-month and one-year follow-ups.

Measures

Sleep outcomes.

Self-reported insomnia symptom severity was measured using the seven-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Bastien, Vallières, & Morin, 2001; Morin, 1993). Summed scores range from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating more severe insomnia. The ISI has good sensitivity in detecting clinical cases of insomnia, is sensitive to treatment response, and has been validated for online delivery (Thorndike et al., 2011).

Minutes of sleep onset latency (SOL) and wake after sleep onset (WASO) were obtained from daily sleep diaries (Carney et al., 2012) collected online, prospectively for two weeks at each time point. Difficulty initiating sleep or maintaining sleep are typically defined by 30 minutes or more of SOL or WASO, respectively (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), so fewer minutes of SOL and WASO indicate better sleep. SOL and WASO data were skewed and were therefore log-transformed before analysis, as previously reported (Ritterband et al., 2017).

Pain interference.

Participants were divided into one of three groups according to their baseline response to the SF-12 pain interference item (“During the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work [including both work outside of the home and housework]?”; Ware Jr, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996): (1) No Pain Interference (responded “Not at all” [n=92]); (2) Some Pain Interference (responded “A little bit” [n=29]); and (3) Moderate/Severe Pain Interference (responded “Moderately” [n=20], “Quite a bit” [n=6], or “Extremely” [n=4], total group n=30). This item has demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability (Huo, Guo, Shenkman, & Muller, 2018).

Analysis Plan

Sample characteristics were summarized by pain interference group using descriptive statistics and differences by pain interference group were examined, except where the frequencies per cell violated assumptions for chi-square tests (nobserved/cell<5). The primary research question examined whether change in sleep outcomes (i.e., ISI, SOL, WASO) differed across individuals in the SHUTi condition according to pain interference using three (pain interference group) by four (time point) linear mixed-effects (LME) models for repeated measures with robust standard errors. Time point was modeled as a categorical variable, meaning that findings are interpreted as the difference between baseline sleep outcome score and each of the three follow-up time points, respectively. The interaction effects of pain interference group by time point evaluated whether change in sleep outcomes differed as a function of pain interference. Post-hoc individual contrasts were planned to probe statistically significant interaction effects. Statistical significance was set at p<.05.

RESULTS

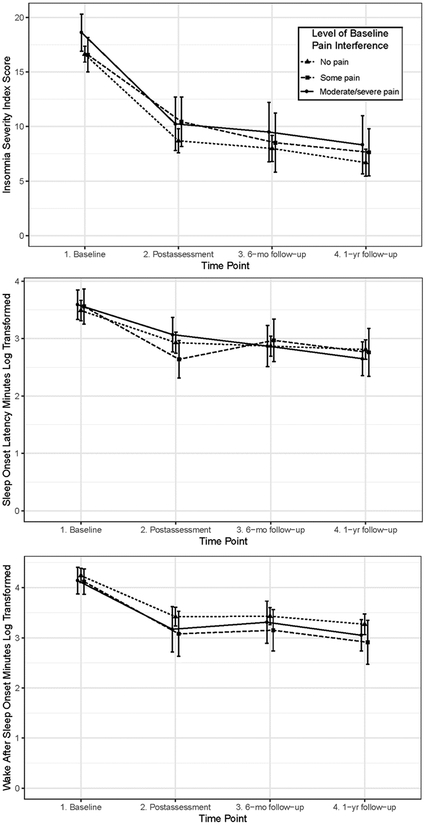

Demographic and clinical characteristics for each pain interference group are listed in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics by pain interference group (ps>.05). Table 2 presents results for the three LME models. There was no overall main effect of pain interference group on ISI scores (p=.27), SOL (p=.86), or WASO (p=.29), meaning that overall change in sleep outcomes did not differ between pain interference groups. All three sleep outcomes significantly decreased from baseline to each of the three follow-up time points (ps<.0001; see Figure 1).

Table 1:

Sample Description

| No Pain Interference (n=92) | Some Pain Interference (n=29) | Moderate/Severe Pain Interference (n=30) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M [SD])‡ | 44.41 (11.51) | 43.07 (11.06) | 42.36 (11.28) |

| Gender (Female)† | 59 (64.1) | 25 (86.2) | 19 (63.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White)‡ | 82 (89.1) | 23 (79.3) | 23 (76.7) |

| Education (≤High school)† | 11 (12.0) | 3 (10.3) | 4 (13.3) |

| Employment (≥Part time)‡ | 69 (75.0) | 23 (79.3) | 21 (70.0) |

| Comorbid health condition (Yes)a‡ | 28 (30.4) | 8 (27.6) | 6 (20.0) |

| Years of sleep difficulties (Med [IQR])‡ | 10 (5.0–15.0) | 10 (4.0–14.5) | 10 (7.1–18.5) |

| Comfort with Internet (Very)† | 84 (91.3) | 26 (89.7) | 25 (83.3) |

| Completed SHUTi (Yes)‡ | 54 (62.8) | 20 (74.1) | 17 (60.7) |

| Sleep Difficulty Variables (M [SD]) | |||

| Baseline | |||

| Insomnia Severity Index* | 16.64 (3.53) | 16.59 (4.31) | 18.63 (4.75) |

| Sleep Onset Latency (log transformed minutes)‡ | 3.49 (0.86) | 3.56 (0.85) | 3.59 (0.72) |

| Wake After Sleep Onset (log transformed minutes)‡ | 4.24 (0.70) | 4.12 (0.70) | 4.14 (0.75) |

| Post-assessment | |||

| Insomnia Severity Index‡ | 8.70 (5.06) | 10.44 (6.00) | 10.25 (6.13) |

| Sleep Onset Latency (log transformed minutes)‡ | 2.93 (0.85) | 2.64 (0.82) | 3.07 (0.73) |

| Wake After Sleep Onset (log transformed minutes)‡ | 3.42 (0.85) | 3.08 (1.11) | 3.17 (1.10) |

| 6-mo Follow-up | |||

| Insomnia Severity Index‡ | 7.99 (5.19) | 8.52 (6.33) | 9.50 (6.52) |

| Sleep Onset Latency (log transformed minutes)‡ | 2.87 (0.75) | 2.97 (0.87) | 2.87 (0.84) |

| Wake After Sleep Onset (log transformed minutes)‡ | 3.43 (0.73) | 3.15 (0.96) | 3.31 (0.99) |

| 1-y Follow-up | |||

| Insomnia Severity Index‡ | 6.96 (5.50) | 7.64 (5.16) | 8.32 (6.82) |

| Sleep Onset Latency (log transformed minutes)‡ | 2.81 (0.73) | 2.76 (1.00) | 2.65 (0.76) |

| Wake After Sleep Onset (log transformed minutes)‡ | 3.27 (0.91) | 2.91 (1.05) | 3.05 (0.79) |

Note.

Chi-square test of independence not run (n<5 in a cell).

Comparison test p>.05.

Comparison test p=.05.

Health conditions self-reported: cancer, diabetes, heart disease including heart attack, high blood pressure, asthma or lung problems, stroke; Test compared individuals reporting “Yes” to one or more conditions versus those who reported “I have not had any of these.”

Table 2:

Linear Mixed Effects Model for Change in Sleep Outcomes among Participants Assigned to SHUTi by Pain Interference Group

| Insomnia Severity Index | Sleep Onset Latency* | Wake After Sleep Onset* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | [95% CI] | p | b | [95% CI] | p | b | [95% CI] | p | |

| 16.64 | [15.92,17.37] | <.0001 | 3.49 | [3.32,3.67] | <.0001 | 4.24 | [4.10,4.39] | <.0001 | |

| Pain Interference Group | F(2, 148)=1.33, p=.27 | F(2, 148)=0.15, p=.86 | F(2, 148)=1.24, p=.29 | ||||||

| No Pain Interference | REF | REF | REF | ||||||

| Some Pain Interference | −0.06 | [−1.77,1.66] | .95 | 0.06 | [−0.29,0.42] | .73 | −0.13 | [−0.42,0.16] | .39 |

| Moderate/Severe Pain Interference | 1.99 | [0.16,3.83] | .03 | 0.16 | [−0.21,0.41] | .53 | −0.11 | [−0.41,0.20] | .49 |

| Time | F(3, 360)=117.05, p<.0001 | F(3, 353)=0.42, p<.0001 | F(3, 353)=46.75, p<.0001 | ||||||

| Baseline | REF | REF | REF | ||||||

| Post-assessment | −7.96 | [−9.04,−6.88] | <.0001 | −0.58 | [−0.75,−0.42] | <.0001 | −0.83 | [−1.03,−0.63] | <.0001 |

| 6-mo Follow-up | −8.44 | [−9.61,−7.27] | <.0001 | −0.64 | [−0.79,−0.49] | <.0001 | −0.79 | [−0.98,−0.60] | <.0001 |

| 1-y Follow-up | −9.39 | [−10.65,−8.13] | <.0001 | −0.69 | [−0.84,−0.55] | <.0001 | −0.94 | [−1.16,−0.72] | <.0001 |

| Pain Interference Group X Time Interaction | F(6, 360)=0.61, p=.72 | F(6, 353)=2.25, p=.04 | F(6, 353)=0.39, p=.88 | ||||||

| Some Pain Interference | |||||||||

| Post-assessment | 1.79 | [−0.38,3.97] | .11 | −0.31 | [−0.67,0.06] | .10 | −0.17 | [−0.59,0.25] | .43 |

| 6-mo Follow-up | 0.91 | [−1.35,3.17] | .42 | 0.03 | [−0.38,0.43] | .90 | −0.07 | [−0.51,0.37] | .76 |

| 1-y Follow-up | 1.00 | [−1.61,3.61] | .46 | −0.13 | [−0.51,0.25] | .51 | −0.19 | [−0.63,0.25] | .39 |

| Moderate/Severe Pain Interference | |||||||||

| Post-assessment | −0.36 | [−2.58,1.86] | .75 | 0.06 | [−0.19,0.30] | .65 | −0.14 | [−0.60,0.31] | .54 |

| 6-mo Follow-up | −0.70 | [−3.12,1.73] | .57 | −0.01 | [−0.31,0.30] | .97 | 0.06 | [−0.37,0.50] | .77 |

| 1-y Follow-up | −0.85 | [−3.44,1.74] | .52 | −0.21 | [−0.48,0.06] | .12 | −0.12 | [−0.50,0.26] | .54 |

Log-transformed scores; Note: F statistics from Type III Tests of Mixed Effects. Using Likelihood Ratio Tests and the AIC information comparisons, the best fitting model for each of the 3 outcomes was chosen starting from a model with random intercept, random slopes (or coefficients) and unstructured correlations to a more restricted model with random intercept only and no random slopes.

Figure 1:

Interaction Plots of Sleep Outcomes among Participants Assigned to SHUTi by Pain Interference Group

The interaction effect between time point and pain interference group was not significant for ISI (p=.72) or WASO (p=.88), meaning that change in ISI and WASO from baseline to follow-up time points were similar regardless of level of pre-treatment pain interference. However, there was a significant interaction between time point and pain interference group for SOL (p=.04). This effect is due to differences between groups from post-assessment to 6-month follow-up: Post-hoc individual contrasts revealed that those in the “some pain interference” group reported a small increase in SOL from post-treatment to six-month follow-up (d=0.16). In contrast, those in the “no pain interference” and “moderate/severe pain interference” groups demonstrated a small decrease in SOL from immediate post−treatment to 6-month follow-up (ds=−0.14, −0.13, respectively; post-hoc contrast ps<.02 [data not shown]).

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of a national (U.S.) trial, findings indicated that individuals assigned to receive Internet-delivered CBT-I (SHUTi) reported lasting improvements in their sleep, regardless of their level of pre-treatment pain interference. Results are consistent with prior studies of CBT-I, delivered alone or in combination with CBT for pain management, demonstrating benefits to individuals with comorbid insomnia and chronic pain (McCurry et al., 2014; Vitiello et al., 2013, 2009). Notably, this is only the second study to examine, and demonstrate, sustained CBT-I treatment benefits through a one-year follow-up among individuals with comorbid insomnia and pain interference (Vitiello et al., 2009). Moreover, this is the first evidence of significant and long-term sleep benefits to individuals with pain interference from a fully-automated, self-guided Internet-delivered CBT-I program.

No long-term differences among groups emerged for self-reported insomnia severity or time awake after initially falling asleep. These findings suggest that, regardless of pre-intervention pain interference, individuals perceived lasting benefits to their sleep from SHUTi. Sustained reductions in sleep disruption from night wakings may be particularly important for individuals with pain, given experimental effects of sleep fragmentation on mechanisms of chronic pain like pain threshold (Lentz, Landis, Rothermel, & Shaver, 1999) and inflammation (Poroyko et al., 2016).

A group difference was found related to sleep onset latency (SOL). Individuals with “some” pain interference at pre-treatment showed a precipitous decline in their SOL over the course of treatment, but then a small rebound in SOL over the six months post-intervention. This pattern contrasts with the continued decline in SOL among those reporting “no pain interference” and “moderate/severe pain interference” at pre-treatment. Importantly, the approximately 10 minute average SOL difference between those in the “some pain interference” versus “no pain interference” and “moderate/severe pain interference” groups at six-month follow-up is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. A graded effect (i.e., outcomes increasingly worse as pain interference worsens) would be expected if level of pain interference was responsible for the differences found. In particular, although we could not evaluate more complex models by gender, it is important to note that there were approximately 34 percent more females endorsing some pain relative to no pain or moderate/severe pain. Women have a higher prevalence of insomnia (Morin et al., 2006) and chronic pain (Bouhassira et al., 2008), as well as a stronger association between insomnia and chronic pain (Skarpsno et al., 2018). As such, further study to replicate this effect is warranted among a larger and more diverse sample to better understand how treatment benefits for sleep initiation difficulties may be best maintained among all users.

Although further study is needed, findings that pre-intervention pain interference did not determine the magnitude or duration of individuals’ overall treatment benefits from SHUTi provides preliminary evidence to suggest that individuals with co-occurring insomnia and pain interference may benefit from Internet-delivered CBT-I that is entirely self-guided. Our findings suggest that standard Internet-delivered CBT-I improves sleep outcomes among individuals with co-occurring insomnia and pain, and as such, pain-specific tailoring may not be necessary to produce positive clinical outcomes. Such findings are promising, given access to traditional clinic-based CBT-I is severely limited by the insufficient number of clinicians specializing in behavioral insomnia treatment (DeAngelis, 2008; Perlis & Smith, 2008). Moreover, individuals with pain interference report transportation and time conflicts as primary barriers to participating in behavioral interventions (Austrian, Kerns, & Reid, 2005). Taken together, findings suggest the significant promise of an Internet-based treatment, accessible at home and on-demand, to deliver care to individuals otherwise unable to readily access high-quality behavioral insomnia treatment.

There are important limitations that should be considered when interpreting findings from this study. The assessment of pain in the current study was limited to a single item assessing pain interference. Characteristics of pain including intensity, quality, and location were not assessed, and it is not known whether participants in this study have diagnosed chronic pain conditions, although it should be noted that single-item pain scales are routinely used to efficiently capture specific facets of respondents’ idiopathic pain experiences (Hawker, Mian, Kendzerska, & French, 2011). In addition, this is a secondary analysis of data from a clinical trial that did not specifically recruit participants based on their premorbid pain interference. This means that our sample size was not set a priori to power these analyses, and that the majority of this sample did not endorse having any pain interference. To minimize bias, we utilized a linear mixed-effects modeling approach, which are preferred for unbalanced designs and do not lose power when instances of missing data are present, unlike ANOVA-based approaches (Pinheiro & Bates, 2000; Quené & Van den Bergh, 2004).

Future studies are warranted to replicate findings that individuals with comorbid insomnia and pain interference demonstrate sustained treatment benefits from a standard, fully-automated Internet-delivered CBT-I approach. For any such future trials, a larger sample with purposeful sampling to achieve balance and diversity with respect to sociodemographic characteristics, pain conditions, and level of pain interference is necessary. A sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial (SMART; Murphy, 2005) may be particularly useful to advance this work by identifying whether participants showing suboptimal treatment outcomes benefit from adjunctive pain-related intervention. Such research could ultimately result in an adaptive Internet-delivered CBT-I intervention that provides the right care to the right individuals at the right time - and nothing more - meaning that all individuals with insomnia receive the most effective and efficient treatment.

Although follow-up study is warranted, this secondary data analysis of a large-scale treatment trial provides novel evidence that adults with insomnia, regardless of their level of pre-existing pain interference, are likely to experience long-lasting treatment benefits from Internet-delivered CBT-I. Widespread dissemination of CBT-I by the Internet holds significant promise for individuals with insomnia and pain in a more accessible, convenient, and cost-effective way.

Funding acknowledgement:

This study was supported by grant R01-MH86758 (PI: Ritterband) from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Shaffer was supported by grant T32-CA009461 (PI: Ostroff) and Cancer Center Support Grant P30-CA008748 (PI: Thompson) from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts: Shaffer, Camacho, Lord, Chow, Palermo, Law, and Ingersoll have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Thorndike and Ritterband report having equity ownership in BeHealth Solutions, LLC, a company that develops and makes available products related to the research reported in this article. Specifically, BeHealth Solutions, LLC, has licensed the Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi) program and the software platform on which it was built from the University of Virginia. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of Virginia in accord with its conflict of interest policy.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

REFERENCES

- Association A. P. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5). [Google Scholar]

- Austrian JS, Kerns RD, & Reid MC (2005). Perceived Barriers to Trying Self-Management Approaches for Chronic Pain in Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(5), 856–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, & Morin CM (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney CE, Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Krystal AD, Lichstein KL, & Morin CM (2012). The consensus sleep diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep, 35(2), 287–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie SR, Wilson KG, Pontefract AJ, & deLaplante L (2000). Cognitive behavioral treatment of insomnia secondary to chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis T (2008). Wake up to a new practice opportunity. Monitor on Psychology, 39(1), 24. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Krystal AD, & Rice JR (2005). Behavioral insomnia therapy for fibromyalgia patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 165(21), 2527–2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, & French M (2011). Measures of adult pain. Arthritis Care & Research, 63(S11), S240–S252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo T, Guo Y, Shenkman E, & Muller K (2018). Assessing the reliability of the short form 12 (SF-12) health survey in adults with mental health conditions: a report from the wellness incentive and navigation (WIN) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungquist CR, O’Brien C, Matteson-Rusby S, Smith MT, Pigeon WR, Xia Y, … Perlis ML (2010). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain. Sleep Medicine, 11(3), 302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffel EA, Koffel JB, & Gehrman PR (2015). A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 19, 6–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz MJ, Landis CA, Rothermel J, & Shaver JL (1999). Effects of selective slow wave sleep disruption on musculoskeletal pain and fatigue in middle aged women. The Journal of Rheumatology, 26(7), 1586–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez MP, Miró E, Sánchez AI, Díaz-Piedra C, Cáliz R, Vlaeyen JW, & Buela-Casal G (2014). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and sleep hygiene in fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(4), 683–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Korff MV, Balderson BH, Baker LD, Rybarczyk BD, & Vitiello MV (2014). Who benefits from CBT for insomnia in primary care? Important patient selection and trial design lessons from longitudinal results of the Lifestyles trial. Sleep, 37(2), 299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miró E, Lupiáñez J, Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Díaz-Piedra C, Guzmán MA, & Buela-Casal G (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia improves attentional function in fibromyalgia syndrome: A pilot, randomized controlled trial. Journal of Health Psychology, 16(5), 770–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM (1993). Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management In Treatment Manuals for Practitioners. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, & Mérette C (2006). Epidemiology of insomnia: Prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Medicine, 7(2), 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, & Smith MT (2008). How can we make CBT-I and other BSM services widely available? Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 4(1), 11–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigeon WR, Moynihan J, Matteson-Rusby S, Jungquist CR, Xia Y, Tu X, & Perlis ML (2012). Comparative effectiveness of CBT interventions for co-morbid chronic pain & insomnia: A pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(11), 685–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poroyko VA, Carreras A, Khalyfa A, Khalyfa AA, Leone V, Peris E, … Hubert N (2016). Chronic sleep disruption alters gut microbiota, induces systemic and adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance in mice. Scientific Reports, 6, 35405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Ingersoll KS, Lord HR, Gonder-Frederick L, Frederick C, … Morin CM (2017). Effect of a web-based cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia intervention with 1-year follow-up: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(1), 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez AI, Díaz-Piedra C, Miró E, Martínez MP, Gálvez R, & Buela-Casal G (2012). Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia on polysomnographic parameters in fibromyalgia patients. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 12(1), 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, & Sateia M (2008). Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. 4, 487–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MT, & Haythornthwaite JA (2004). How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 8(2), 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang NK (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sleep abnormalities of chronic pain patients. Current Rheumatology Reports, 11(6), 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang NK, Goodchild CE, & Salkovskis PM (2012). Hybrid cognitive-behaviour therapy for individuals with insomnia and chronic pain: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(12), 814–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike FP, Saylor DK, Bailey ET, Gonder-Frederick L, Morin CM, & Ritterband LM (2008). Development and perceived utility and impact of an Internet intervention for insomnia. E-Journal of Applied Psychology: Clinical and Social Issues, 4(2), 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Balderson BH, Baker LD, Keefe FJ, … Korff MV (2013). Cognitive‐behavioral treatment for comorbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: The lifestyles randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(6), 947–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello MV, Rybarczyk B, Korff MV, & Stepanski EJ (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves sleep and decreases pain in older adults with co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 5(4), 355–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, & Keller SD (1996). A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]