Abstract

Background

Fetal growth, an important predictor of cardiometabolic diseases in adults, is influenced by maternal and fetal genetic and environmental factors.

Objective

We investigated the association between maternal lipid genetic risk score (GRS) and fetal growth among four US racial/ethnic populations (Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians).

Methods

We extracted genotype data for 2,008 pregnant women recruited in the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singleton cohort with up to 6 standardized ultrasound examinations. GRS was calculated using 240 single nucleotide polymorphisms previously associated with higher total cholesterol (GRSTChol), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (GRSLDLc) and triglycerides (GRSTG), and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (GRSHDLc).

Results

At 40 gestation weeks, a unit increase in GRSTG was associated with 11.4 g higher fetal weight (95% CI, 2.8 to 20.0 g) among normal-weight Whites, 26.3 g (95% CI, 6.0 to 46.6 g) among obese Blacks, and 30.8 g (95% CI, 6.3 to 55.3 g) among obese Hispanics. Higher GRSHDLc was associated with increased fetal weight across 36–40 weeks among normal-weight Whites and across 13–20 weeks among normal-weight Asians, but with decreased fetal weight across 26–40 weeks among normal-weight Hispanics. Higher GRSTChol was suggestively associated with increased fetal weight in males and decreased in females. Associations remained consistent after adjustment for serum lipids.

Conclusion

Associations between fetal weight and maternal lipid GRS appear to vary by maternal race/ethnic group, obesity status and offspring sex. Genetic susceptibility to unfavorable lipid profiles contributes to fetal growth differences even among normal-weight women suggesting a potential future application in predicting aberrant fetal growth.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Keywords: genetic risk score, maternal lipid traits, fetal growth, birth weight

Introduction

Fetal growth is an important predictor of adulthood cardiometabolic disease risk.[1] Several studies have provided evidence for influence of maternal serum lipid levels during pregnancy on fetal growth.[2–5] There is some evidence that genetic factors that influence lipid levels may also influence birth weight. Among 12 maternal genetic loci associated with birth weight in a recent GWAS,[6] L3MBTL3 and EBF1 have been implicated in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc),[7] and GCK in triglyceride[8] levels. Moreover, TCF7L2 gene loci associated with total cholesterol, HDLc, triglycerides[9] and birth weight are highly correlated.[6] Similarly, MTNR1B gene loci associated with the metabolic syndrome[10] and birth weight[6] are strongly correlated. Placental expression of known lipid metabolism genes LPL[11] and maternal apoE gene locus[12] are also associated with birth size. However, the role of maternal lipid trait genetics on longitudinal fetal growth has not been studied.

The relationship between maternal lipid trait genetic factors and fetal growth is likely to be complex,[13, 14] with differences based on maternal race/ethnicity, obesity status, and offspring sex. For example, the genetic contribution to lipid traits has been shown to vary by ancestry[15] and the levels of serum lipids during pregnancy exert different effects on birthweight depending on maternal adiposity status.[16–19] The effect of maternal lipid trait genes may also vary by offspring sex given that evidence for sex differences in the regulation of lipid levels by endogenous estrogens and androgens in utero exist.[20]

Our objective was to investigate the association between maternal genetic susceptibility for higher total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDLc, and lower HDLc and fetal growth among four US race/ethnic populations (Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians) using genetic risk scores based on 279 genetic loci known to be associated with serum lipid levels by genome-wide association studies (GWAS).[15, 21, 22] In addition, we examined whether these associations differed by maternal pre-pregnancy obesity status and offspring sex.

Methods

Study setting and study population

The study was based on the 2,802 participants of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Fetal Growth Studies - Singleton cohort that included pregnant women without past-pregnancy complications, pre-pregnancy hypertension, diabetes, renal/autoimmune disease, psychiatric disorder, cancer, HIV or AIDs, and without a history of cigarette smoking in the past 6 months, use of illicit drugs in the past year or consumption of 1 or more alcoholic drinks per day during enrollment.[23] Women were recruited before 13 weeks gestation (WG) between July 2009 and January 2013 from 12 clinic sites within the US. Gestational age was determined using the date of the last menstrual period and confirmed by ultrasound between 8 WG to 13 WG and 6 days.[24] Women self-reported their race/ethnicity as Non-Hispanic White (White), Non-Hispanic Black (Black), Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific Islander (Asian). Detailed recruitment and inclusion criteria have been reported previously.[24] From the 2,802 pregnant women originally enrolled, we excluded 737 (26.3 %) women with no genetic data, 42 (1.6 %) women with fetal deaths (miscarriage, fetal death or voluntary termination of pregnancy) and 15 (0.5%) women who exited the study. Data from the remaining 2,008 pregnant women (610 White, 613 Black, 552 Hispanic and 233 Asian) were taken forward for analyses.

DNA extraction, genotyping and blood lipid levels

DNA was extracted from stored blood samples collected at enrollment. Genotyping was performed in 2017 using the Infinium Multi-Ethnic Global BeadChip array (Illumina), that has >1.7 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Genotypes were imputed with the Michigan Imputation Server[25] implementing Eagle2[26] for haplotype phasing, followed by Minimac2[27] for imputing non-typed SNPs with 1000 Genomes Phase 3 reference sequence data.[28] Total cholesterol, HDLc, LDLc, and triglyceride levels were measured using stored serum in −80°F freezers isolated from non-fasting blood samples collected at enrollment.[29] Total cholesterol, HDLc and triglycerides were directly measured using the Roche COBAS 6000 chemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). LDLc was calculated using the Friedewald formula.[30]

Exposure assessment

We extracted data on 279 SNPs (107 SNPs associated with total cholesterol, 112 SNPs for HDLc, 84 SNPs for LDLc, and 80 SNPs for triglycerides) known to be associated with blood lipid levels at genome-wide significance thresholds (p ≤ 5×10−8) from 3 published large-scale GWAS.[15, 21, 22] After removing 39 SNPs which were not available across the four race/ethnic groups, we included 95 SNPs in GRS for higher total cholesterol (GRSTChol), 100 SNPs in GRS for lower HDLc (GRSHDLc), 71 SNPs in GRS for higher LDLc (GRSLDLc), and 68 SNPs in GRS for higher triglycerides (GRSTG) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The GRS was constructed by summing the number of alleles of each SNP related to higher total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDLc, and lower HDLc.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was estimated fetal weight. After the first ultrasound that confirmed gestational age, pregnant women underwent 5 standardized ultrasounds at a priori defined gestational ages.[23, 24, 31] Measurement of fetal growth was performed using standardized obstetrical ultrasonography protocols and on identical equipment (Voluson E8; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). All dedicated sonographers underwent an intensive training and evaluation period.[32] The quality control showed that measurements between site sonographers and experts had high correlation (> 0.99) and low coefficient of variation (< 3%).[31] For each ultrasound, fetal weight was estimated from head circumference, abdominal circumference and femur length using the Hadlock formula.[33]

To support our results on fetal weight, we also tested for associations between GRS and birth weight as a secondary outcome. Birth weight was used as a continuous outcome and as a binary outcome using large- and small-for-gestational age (LGA, > 90th and SGA, < 10th percentile by sex and gestational age at delivery, respectively) based on a published US reference.[34]

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were stratified by maternal race/ethnicity to avoid spurious associations or distortions in effect estimates between genetic susceptibility and fetal growth due to allele frequency differences between race/ethnic groups.[35] We generated principal components from multi-dimensional scaling analysis of a set of uncorrelated SNPs for further adjustment in the analysis to account for population admixture.[36] To assess the relevance of the GRS of lipid traits to circulating lipid levels, we evaluated whether GRS was associated with maternal blood lipid levels at enrollment adjusting for maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) and the first five principal components.

We tested for associations between fetal weight and GRSTChol, GRSHDLc, GRSLDLc, and GRSTG at each gestational week from 13 to 40 WG using linear regression analyses. We also tested for associations between birth weight and GRSTChol, GRSHDLc, GRSLDLc, and GRSTG using linear regression analysis and with LGA and SGA compared to appropriate-for-gestational age using logistic regression analysis. All regression analyses were adjusted for maternal age (years, continuous), pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2, continuous), highest level of education (less than high school, high school diploma or GED or equivalent, some college or associate degree, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree or advanced degree), marital status (not married vs. living as married), parity (0, 1, 2, 3 or more), gestational age at delivery (weeks, continuous), offspring sex (male, female), diabetes (none vs. yes), pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases (none vs. gestational hypertension or preeclampsia) and the first five principal components (continuous). Analyses were then stratified by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI status (normal-weight, < 25 kg/m2; overweight, 25 to 30 kg/m2; and obese, ≥ 30 kg/m2) and by offspring sex. For a sensitivity analysis we further adjusted for participating site, mood disorders medication and gestational diabetes medication (insulin or metformin). Finally, maternal serum lipids at enrollment (HDLc, LDLc and triglycerides) were added to the models in further analyses.

A P-Value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Quality control of the genome-wide data and calculation of the principal components were done with PLINK 1.9 (www.coggenomics.org/plink/1.9/).[37] Analyses were performed with STATA 14 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

The average fetal weight was highest among Whites throughout pregnancy, and lowest among Asians until late in pregnancy when the mean fetal weight became lowest among Blacks (P < .001). The mean birth weight ranged from 3216 g (SD: 520 g) among Blacks to 3449 g (SD: 483 g) among Whites (P < .001). The proportion of babies born SGA varied from 5% in Whites to 13% in Blacks. Correspondingly, the proportion of LGA varied from 6% in Blacks to 13% in Whites (P < .001) (Table 1). The median plasma cotinine level was 0.01 ng/mL (5th-95th percentile: 0.00 – 0.52 ng/mL) consistent with no active smoking.[38] The highest GRS varied by maternal race with GRSTChol and GRSHDLc highest among Asians (P < .001), GRSLDLc among Whites (P <.01), and GRSTG among Hispanics (P < .001). Only GRSTG differed by BMI among white women (P <.01, eTable 2 in the Supplement). As expected, GRSTChol, GRSLDLc, GRSTG, and GRSHDLc were associated with the corresponding lipid levels. The correlations between GRS and lipid levels were weaker among Blacks than among other race/ethnic groups (eTables 3–4 in the Supplement).

Table 1:

Description of the study population by race/ethnicity (N=2,008 from the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singleton cohort)

| White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | P Value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, No. | 610 | 613 | 552 | 233 | |||||

| Highest level of education, No. (%) | < .001 | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 7 | (1.1) | 76 | (12.4) | 148 | (26.8) | 18 | (7.7) | |

| High school diploma or GED or equivalent | 37 | (6.1) | 180 | (29.4) | 139 | (25.2) | 31 | (13.3) | |

| College or Associate degree | 117 | (19.2) | 236 | (38.5) | 181 | (32.8) | 44 | (18.9) | |

| Bachelor degree | 250 | (41.0) | 79 | (12.9) | 64 | (11.6) | 76 | (32.6) | |

| Master or Advanced degree | 199 | (32.6) | 42 | (6.9) | 20 | (3.6) | 64 | (27.5) | |

| Parity, No. (%) | < .001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 327 | (53.6) | 284 | (46.3) | 195 | (35.3) | 115 | (49.4) | |

| 1 | 202 | (33.1) | 192 | (31.3) | 206 | (37.3) | 104 | (44.6) | |

| 2 | 62 | (10.2) | 95 | (15.5) | 94 | (17.0) | 13 | (5.6) | |

| 3 or more | 19 | (3.1) | 42 | (6.9) | 57 | (10.3) | 1 | (0.4) | |

| Marital Status, No. (%) | < .001 | ||||||||

| Not married | 43 | (7.0) | 316 | (51.5) | 143 | (25.9) | 14 | (6.0) | |

| Married or living with someone | 567 | (93.0) | 296 | (48.3) | 409 | (74.1) | 219 | (94.0) | |

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Age at enrollment, mean (SD), y | 30.3 | (4.5) | 25.4 | (5.3) | 27.1 | (5.5) | 30.7 | (4.6) | < .001 |

| Pre-pregnancy body-mass index (BMI), No. (%), kg/m2 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Less than 25 | 370 | (60.7) | 288 | (47.0) | 276 | (50.0) | 190 | (81.5) | |

| [25 – 30[ | 135 | (22.1) | 185 | (30.2) | 178 | (32.2) | 42 | (18.0) | |

| 30 or more | 105 | (16.2) | 140 | (22.9) | 98 | (17.7) | 1 | (0.4) | |

| Gestational diabetes, No. (%) | .22 | ||||||||

| None | 609 | (99.8) | 607 | (99.0) | 550 | (99.6) | 232 | (99.6) | |

| Yes | 1 | (0.2) | 6 | (1.0) | 2 | (0.4) | 1 | (0.4) | |

| Pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases, No. (%) | .01 | ||||||||

| None | 587 | (96.2) | 574 | (93.6) | 532 | (96.4) | 230 | (98.7) | |

| Gestational hypertension or Preeclampsia | 23 | (3.8) | 39 | (6.4) | 20 | (3.6) | 3 | (1.3) | |

| Gestational diabetes medication, No. (%) | .53 | ||||||||

| No | 582 | (95.4) | 575 | (93.8) | 521 | (94.4) | 204 | (87.6) | |

| Yes | 1 | (0.2) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0.4) | |

| Missing** | 27 | (4.4) | 37 | (6.0) | 31 | (5.6) | 28 | (12.0) | |

| Mood disorder medication, No. (%) | .09 | ||||||||

| No | 573 | (93.9) | 564 | (92.0) | 519 | (94.0) | 203 | (87.1) | |

| Yes | 10 | (1.6) | 12 | (2.0) | 2 | (0.4) | 2 | (0.9) | |

| Missing** | 27 | (4.4) | 37 | (6.0) | 31 | (5.6) | 28 | (12.0) | |

| GA at delivery, mean (SD), week | 39.3 | (1.5) | 39.1 | (1.8) | 39.3 | (1.5) | 39.3 | (1.2) | .10 |

| Offspring gender, No. (%) | .48 | ||||||||

| Male | 310 | (50.8) | 278 | (45.4) | 261 | (47.3) | 105 | (45.1) | |

| Female | 271 | (44.4) | 292 | (47.6) | 256 | (46.4) | 101 | (43.3) | |

| Missing | 29 | (4.8) | 43 | (7.0) | 35 | (6.3) | 27 | (11.6) | |

| Estimated fetal weight, mean (SD), g | |||||||||

| At 13 weeks and 6 days | 86 | (7.6) | 85 | (7.6) | 84 | (8.1) | 83 | (8.5) | < .001 |

| At 20 weeks | 336 | (30.3) | 328 | (30.6) | 327 | (32.7) | 322 | (33.1) | < .001 |

| At 27 weeks and 6 days | 1180 | (113) | 1129 | (114) | 1140 | (122) | 1115 | (118) | < .001 |

| At 40 weeks | 3775 | (455) | 3478 | (426) | 3595 | (473) | 3494 | (433) | < .001 |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 3449 | (483) | 3216 | (520) | 3346 | (488) | 3323 | (424) | < .001 |

| Birth weight classification, No. (%) | |||||||||

| SGA (< 10th percentile) | 30 | (5.2) | 73 | (12.8) | 48 | (9.3) | 21 | (10.2) | < .001 |

| LGA (> 90th percentile) | 77 | (13.3) | 31 | (5.5) | 41 | (7.9) | 15 | (7.3) | < .001 |

| Serum lipids levels, mean (SD), mg/dl | |||||||||

| Total Cholesterol | 190.6 | (30.6) | 181.9 | (31.8) | 186.9 | (30.7) | 182.7 | (28.2) | < .001 |

| HDL cholesterol | 65.1 | (13.3) | 64.6 | (14.4) | 59.2 | (13.9) | 63.0 | (12.5) | < .001 |

| LDL cholesterol | 102.0 | (26.7) | 96.8 | (28.0) | 100.1 | (25.1) | 91.3 | (24.2) | < .001 |

| Triglycerides | 117.4 | (46.4) | 103.2 | (38.9) | 138.9 | (54.4) | 142.3 | (55.4) | < .001 |

| Genetic Risk Scores, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Total Cholesterol (GRSTChol) | 96.9 | (5.9) | 94.7 | (5.4) | 97.0 | (5.9) | 98.2 | (5.6) | < .001 |

| HDL cholesterol (GRSHDLc) | 93.1 | (6.1) | 94.4 | (5.7) | 92.9 | (6.0) | 98.5 | (5.5) | < .001 |

| LDL cholesterol (GRSLDLc) | 69.8 | (5.0) | 68.9 | (4.5) | 69.4 | (4.8) | 69.7 | (4.5) | .01 |

| Triglycerides (GRSTG) | 67.5 | (5.3) | 71.2 | (4.4) | 72.8 | (5.5) | 72.7 | (5.3) | < .001 |

Abbreviations: GED: General Educational Development; GA: gestational age, SGA: Small-for gestational age; LGA: large-for-gestational age

P Value from chi-squared test or ANOVA test comparing four race/ethnicity groups

No medical records or no medication information

Associations between GRS and fetal weight by gestation week

Results for each gestational week are presented in Figures 1–2 and eFigures 1–4 in the Supplement, and results corresponding to the end of first trimester (13 WG), mid-gestation (20 WG), late second trimester (27 WG) and third trimester (40 WG) of pregnancy are presented in Supplement eTables 5–6. In the overall sample, GRSTG was significantly associated with increased fetal weight among Whites at 39–40 WG (7.4 g, 95% CI, 0.4 to 14.4 g at week 40 per unit increase in GRSTG) (Figure 1 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Associations of GRSTChol, GRSHDLc and GRSLDLc with fetal weight were not significant (eFigures 1–4 in the Supplement).

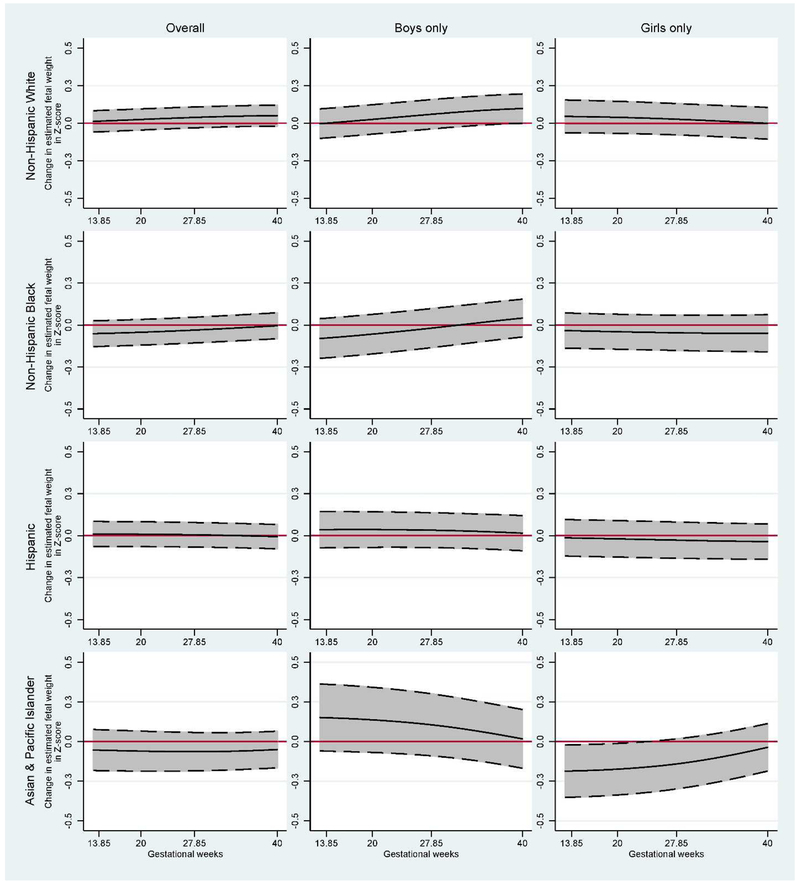

Figure 1:

Estimated fetal weight (EFW) change (in Z-score) for each 5 unit increase in the GRSHDLc and GRSTG stratified by pre-pregnancy BMI (N=2,008 from the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singleton cohort). Middle black solid-lines represent the adjusted change in Z-score; top and bottom dash-lines represent upper and lower 95% confidence interval, respectively; red solid-lines represent the NULL estimates.

Adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, highest level of education, marital status, parity, gestational age at delivery, offspring sex, diabetes, pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases and for the first five genetic principal components.

Figure 2:

Estimated fetal weight change (in Z-score) for each 5 unit increase in the GRSTChol stratified by offspring sex (N=2,008 from the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singleton cohort). Middle black solid-lines represent the adjusted change in Z-score; top and bottom dash-lines represent upper and lower 95% confidence interval, respectively; red solid-lines represent the NULL estimates.

Adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, highest level of education, marital status, parity, gestational age at delivery, offspring sex, diabetes, pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases and for the first five genetic principal components.

In analyses stratified by pre-pregnancy BMI, GRSTG was significantly associated with increased fetal weight across 29–40 WG among normal-weight Whites (11.4 g, 95% CI, 2.8 to 20.0 g at week 40), across 27–40 WG among obese Blacks (26.3 g, 95% CI, 6.1 to 46.6 g at week 40), and across 31–40 WG among obese Hispanics (30.8 g, 95% CI, 6.3 to 55.3 g at week 40). GRSHDLc was significantly associated with increased fetal weight across 36–40 WG among normal-weight Whites and across 13–20 WG among normal-weight Asians, but inversely associated with fetal weight across 26–40 WG among normal-weight Hispanics. GRSLDLc was associated with increased fetal weight throughout pregnancy among obese Whites (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

In analyses stratified by offspring sex, GRSLDLc was significantly associated with increased fetal weight among White women with a female fetus across 28–39 WG (eTable 6 in the Supplement). GRSTChol appeared to be positively associated with fetal weight in males and negatively associated with fetal weight in females (Figure 2). The positive association among males was significant at 40 WG among Whites (8.9 g, 95% CI, 0.1 to 17.8 g) and the inverse association with females was significant across 13–23 WG among Asians. GRSHDLc was significantly associated with increased fetal weight among Asian women with a male fetus across 13–31 WG.

Associations between GRS and weight at birth

GRSTG was positively associated with birth weight among normal-weight Whites and obese Blacks. GRSHDLc was negatively associated with birth weight among obese Hispanics (Table 2). GRSTChol was suggestively associated with higher birth weight among boys and lower birth weight among girls across all race/ethnic groups; however, the associations were not statistically significant (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Table 2:

Birth weight change (in gram) by a unit increase of genetic risk score (GRS) stratified by pre-pregnancy BMI (N=2,008 from the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singleton cohort).

| Overall | Stratified by pre-pregnancy BMI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI < 25 kg/m2 | 25 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2 | BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | ||||||||||

| N | β | (95% CI) | N | β | (95% CI) | N | β | (95% CI) | N | β | (95% CI) | |

| Whites | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 581 | 1.60 | (−3.81 to 7.00) | 350 | 1.87 | (−4.65 to 8.40) | 128 | −0.45 | (−14.17 to 13.28) | 103 | 6.46 | (−7.70 to 20.62) |

| GRSHDLc | 581 | 1.15 | (−3.98 to 6.27) | 350 | 2.68 | (−3.87 to 9.23) | 128 | −0.92 | (−12.52 to 10.68) | 103 | −3.19 | (−16.80 to 10.42) |

| GRSLDLc | 581 | 3.74 | (−2.53 to 10.02) | 350 | 4.21 | (−3.37 to 11.80) | 128 | −3.21 | (−21.19 to 14.77) | 103 | 12.51 | (−2.67 to 27.69) |

| GRSTG | 581 | 5.61 | (−0.35 to 11.56) | 350 | 9.03 | (1.75 to 16.31) | 128 | 2.61 | (−12.11 to 17.34) | 103 | −5.55 | (−21.77 to 10.67) |

| Blacks | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 568 | −1.91 | (−7.75 to 3.92) | 272 | −5.03 | (−13.36 to 3.30) | 157 | −0.52 | (−12.86 to 11.83) | 139 | 3.11 | (−9.78 to 16.01) |

| GRSHDLc | 568 | 2.98 | (−2.48 to 8.44) | 272 | 2.48 | (−5.21 to 10.18) | 157 | −2.21 | (−12.86 to 8.44) | 139 | 8.80 | (−3.88 to 21.47) |

| GRSLDLc | 568 | −3.50 | (−10.62 to 3.62) | 272 | −6.93 | (−17.23 to 3.38) | 157 | 1.29 | (−12.79 to 15.36) | 139 | 2.95 | (−12.91 to 18.81) |

| GRSTG | 568 | 2.58 | (−4.60 to 9.75) | 272 | −1.83 | (−11.64 to 7.99) | 157 | −1.21 | (−16.06 to 13.64) | 139 | 25.59 | (8.07 to 43.10) |

| Hispanics | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 517 | −2.17 | (−8.13 to 3.80) | 260 | −5.41 | (−13.96 to 3.14) | 169 | 4.35 | (−6.56 to 15.27) | 88 | −0.12 | (−17.07 to 16.82) |

| GRSHDLc | 517 | −5.27 | (−11.06 to 0.51) | 260 | −5.81 | (−13.41 to 1.80) | 169 | 1.92 | (−9.77 to 13.61) | 88 | −17.39 | (−34.58 to −0.20) |

| GRSLDLc | 517 | −1.77 | (−9.00 to 5.46) | 260 | −0.72 | (−11.45 to 10.00) | 169 | 4.01 | (−8.66 to 16.68) | 88 | −8.17 | (−28.74 to 12.40) |

| GRSTG | 517 | 3.86 | (−3.18 to 10.91) | 260 | −2.18 | (−11.26 to 6.90) | 169 | 11.72 | (−2.03 to 25.47) | 88 | 22.07 | (−1.08 to 45.22) |

| Asians | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 205 | −5.60 | (−15.07 to 3.86) | 170 | −8.26 | (−18.29 to 1.77) | 34 | 12.12 | (−17.49 to 41.72) | |||

| GRSHDLc | 205 | −3.04 | (−12.83 to 6.75) | 170 | −0.04 | (−10.34 to 10.25) | 34 | −8.65 | (−55.43 to 38.13) | |||

| GRSLDLc | 205 | 4.62 | (−7.22 to 16.45) | 170 | 2.64 | (−10.04 to 15.33) | 34 | 6.68 | (−31.44 to 44.81) | |||

| GRSTG | 205 | −3.97 | (−14.36 to 6.42) | 170 | −4.73 | (−16.35 to 6.89) | 34 | −8.91 | (−40.51 to 22.69) | |||

Adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, highest level of education, marital status, parity, gestational age at delivery, offspring sex, diabetes, pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases and for the first five genetic principal components.

Results for LGA and SGA were in concordance with the fetal and birth weight results. A unit increase in GRSTG was associated with a 10% (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.00) lower risk for SGA among normal-weight Whites, and a 26% (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.98) lower risk for SGA among obese Blacks (eTables 8–9 in the Supplement). GRSTG, GRSTChol and GRSLDLc among Whites were associated with higher risk for having a boy with LGA, lower risk of having a girl who was LGA, and lower risk of having a girl who was SGA, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3:

Genetic risk score (GRS) of lipid traits and risk of large-for-gestational age (LGA) and small-for-gestational age (SGA) stratified by offspring sex (N=2,008 from the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singleton cohort).

| Risk of LGA | Risk of SGA | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys only | Girls only | Boys only | Girls only | |||||||||

| N | OR | (95% CI) | N | OR | (95% CI) | N | OR | (95% CI) | N | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Whites | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 293 | 1.06 | (0.99 to 1.13) | 255 | 0.92 | (0.86 to 0.98) | 225 | 0.96 | (0.88 to 1.05) | 225 | 0.92 | (0.83 to 1.03) |

| GRSHDLc | 293 | 0.99 | (0.93 to 1.05) | 255 | 1.03 | (0.97 to 1.09) | 225 | 1.02 | (0.93 to 1.12) | 225 | 0.99 | (0.90 to 1.09) |

| GRSLDLc | 293 | 1.04 | (0.97 to 1.12) | 255 | 1.00 | (0.92 to 1.08) | 225 | 1.00 | (0.90 to 1.11) | 225 | 0.88 | (0.77 to 1.00) |

| GRSTG | 293 | 1.09 | (1.02 to 1.17) | 255 | 0.99 | (0.92 to 1.06) | 225 | 0.95 | (0.86 to 1.06) | 225 | 0.93 | (0.82 to 1.06) |

| Blacks | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 221 | 1.04 | (0.93 to 1.16) | 224 | 0.94 | (0.82 to 1.06) | 258 | 1.07 | (0.99 to 1.16) | 272 | 0.97 | (0.90 to 1.04) |

| GRSHDLc | 221 | 0.99 | (0.90 to 1.10) | 224 | 1.09 | (0.97 to 1.23) | 258 | 1.00 | (0.93 to 1.07) | 272 | 0.99 | (0.92 to 1.06) |

| GRSLDLc | 221 | 1.05 | (0.92 to 1.20) | 224 | 0.90 | (0.79 to 1.03) | 258 | 1.08 | (0.98 to 1.18) | 272 | 0.99 | (0.91 to 1.08) |

| GRSTG | 221 | 0.96 | (0.85 to 1.10) | 224 | 1.15 | (0.97 to 1.37) | 258 | 0.97 | (0.89 to 1.07) | 272 | 0.95 | (0.87 to 1.04) |

| Hispanics | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 235 | 0.99 | (0.91 to 1.09) | 232 | 1.02 | (0.93 to 1.12) | 208 | 0.98 | (0.91 to 1.06) | 214 | 1.05 | (0.96 to 1.15) |

| GRSHDLc | 235 | 0.98 | (0.90 to 1.07) | 232 | 1.02 | (0.93 to 1.13) | 208 | 1.02 | (0.95 to 1.10) | 214 | 1.02 | (0.95 to 1.11) |

| GRSLDLc | 235 | 0.99 | (0.88 to 1.11) | 232 | 1.03 | (0.91 to 1.16) | 208 | 1.02 | (0.93 to 1.12) | 214 | 1.02 | (0.93 to 1.12) |

| GRSTG | 235 | 1.00 | (0.89 to 1.11) | 232 | 1.02 | (0.90 to 1.15) | 208 | 0.93 | (0.85 to 1.02) | 214 | 1.07 | (0.98 to 1.18) |

| Asians | ||||||||||||

| GRSTChol | 70 | 0.88 | (0.70 to 1.12) | 61 | 1.06 | (0.86 to 1.31) | 70 | 0.89 | (0.69 to 1.13) | 92 | 1.06 | (0.95 to 1.19) |

| GRSHDLc | 70 | 1.41 | (0.93 to 2.14) | 61 | 1.24 | (0.92 to 1.67) | 70 | 1.07 | (0.88 to 1.31) | 92 | 1.02 | (0.90 to 1.16) |

| GRSLDLc | 70 | 1.06 | (0.81 to 1.39) | 61 | 1.25 | (0.93 to 1.67) | 70 | 0.97 | (0.77 to 1.22) | 92 | 1.06 | (0.90 to 1.24) |

| GRSTG | 70 | 0.95 | (0.66 to 1.36) | 61 | 0.95 | (0.79 to 1.15) | 70 | 0.90 | (0.71 to 1.13) | 92 | 1.02 | (0.90 to 1.15) |

Adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, highest level of education, marital status, parity, diabetes, pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases and for the first five genetic principal components

After adjustment for participating site, mood disorders medication and insulin intake during pregnancy, results were similar, only GRSTG was significantly associated with higher birth weight among Whites (eTable 10 in the Supplement).

Analysis adjusted for maternal serum lipid levels

After adjustment for maternal HDLc, LDLc and triglyceride blood levels at enrollment, only the associations of GRSLDLc with higher fetal weight and lower risk of SGA among girls were attenuated. Other results remained significant (eTables 11–13 and eFigures 5–8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this novel investigation of maternal lipid traits genetic risk scores and fetal growth among diverse US women, the effects of lipid GRS were observed to vary by race/ethnic group, maternal obesity status and offspring sex. First, we found a strong positive association between GRSTG and fetal and birth weight among normal-weight Whites and obese Blacks. Further, we found that the associations were not attenuated after adjusting for maternal serum triglyceride levels, which have previously been implicated in higher birth size,[2, 39] suggesting that GRSTG may influence fetal growth beyond the effect due to maternal serum lipid levels in early pregnancy. Second, GRSHDLc was associated with increased fetal weight among normal-weight Whites and Asians but decreased fetal weight among normal-weight and obese Hispanics. Third, GRSLDLc was associated with higher fetal weight and reduced SGA risk among White females. Our observation that the GRSLDLc associations were not significant when adjusted for LDLc levels, suggests that the genetic risk may operate by modulating circulating LDLc, consistent with previous studies that found significant lower LDLc serum levels in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction.[40] Lastly, we observed a tendency for offspring sex-dependent association of GRSTChol with fetal and birth weight resulting in increased weight among males and decreased weight among females.

The possible pathways through which maternal lipid trait genetic risk factors influence fetal growth are not well understood. Lipid trait GRS may impact fetal growth via its influence on maternal serum lipid levels. However, maternal serum lipid levels are also influenced by behaviors such as diet and physical activity.[13] With the exception of LDLc, we observed little difference in effect after adjustment for serum lipids levels, which suggests that these genetic factors may influence fetal growth beyond the contribution of early pregnancy lipid levels. Notably, lipid trait SNPs have been associated with BMI,[41] C-Reactive Protein[42, 43], diabetes,[9] and insulin-like growth factor 1.[44] Effects on fetal growth might also be mediated by the placenta[11] given that trans-placental transport of lipids contributes to the intrauterine environment including oxidation and formation of free fatty acids.[3] Finally, the mechanism could involve shared genes between the mother and the fetus. Since fetal DNA was not available in our study, future studies of fetal lipid genetic risk scores could help understand the independent effects of maternal and fetal genes on fetal growth.

One of the striking findings from our study was that the effect of GRSHDLc on fetal and birth weight varied by race/ethnicity, exhibiting a positive association with weight among normal-weight Whites and Asians and an inverse association among normal-weight and obese Hispanics. Previous studies conducted in Poland,[45] Brazil,[46] and China[39, 47] reported an inverse relationship between plasma HDLc levels and birth weight. Hoffmann et al. reported that HDLc was lower in Hispanic women compared to White women and highlighted that the distribution of lipids explained by GRS varies among ancestry groups.[15] In contrast, we observed that the effect of GRSHDLc on fetal weight remained the same after adjusting for HDLc suggesting that the race/ethnicity differences in the effects of GRSHDLc are not likely to be exclusively mediated by HDLc plasma level in early pregnancy. Variation in fetal growth by maternal race/ethnicity is well known,[24] but the factors that underlie this variation are not well described, particularly with respect to genetic risk differences. We have previously found that the burden of birthweight-reducing genetic variants varies across major population groups,[48] which may partly be due to population differences in risk allele frequencies.[49]

We found significant relationships between maternal GRS for lipid traits and fetal growth among both normal-weight and obese women. A potential explanation of the difference in GRS effect by obesity status could be the metabolic dysregulation[16] or lipid oxidation[50] associated with maternal overweight and obesity, or the differences in fetal growth trajectories between BMI groups.[17]

The associations between GRSTChol and fetal weight varied by offspring sex, where higher GRSTChol was associated with heavier males and lighter females at birth. This effect was significant among male neonates of White mothers and female neonates of Asian mothers. Two prior studies reported increased risk of SGA (<3rd percentile) among Whites and Blacks with higher serum total cholesterol.[12] However, none of the previous studies on total cholesterol and fetal growth have investigated effect modification by offspring sex.[2, 47, 51, 52] Others have reported genetic contributions including X chromosome dosage for sex difference in lipid metabolism and adiposity[53, 54] and sex differences in the effects of SNPs known to be associated with lipids.[15, 21] One study reported a lower correlation of lipid traits among dizygotic opposite-sex twins than dizygotic same-sex twins.[55] Metrustry and colleagues highlighted that the gene NTRK2 known to be associated with LDLc[7] is associated with birth weight among females but not among males.[56] Since male neonates are generally 100 g heavier at birth,[57] the potential pathway could be due to sexual dimorphism in metabolism[56] or differences in endogenous fetal estrogens and androgens[58] which regulate triglycerides and total cholesterol levels.[20]

To our knowledge, this is the first study to test the association between maternal lipid trait genetic risks and fetal growth. Prior studies used maternal serum lipid levels rather than GRS and used birth weight as a proxy for intrauterine fetal growth.[59] However, birth weight does not provide the same information as longitudinal fetal growth and it does not capture the influence on fetal growth trajectories, which we were able to observe. The NICHD Fetal Growth Study has many strengths including its longitudinal design, involvement of race/ethnic diverse populations, and implementation of standardized ultrasound protocols with established quality control. We recognize that our study has limitations. We do not have longitudinal measures of maternal lipid concentrations but were reassured that early lipid concentrations and trajectories of lipids during pregnancy are likely to be comparable within BMI groups.[29] Another limitation is that the GRS was generated using SNPs associated with lipids in predominantly European ancestry population GWAS, which may limit their transferability to other populations.[60]

In conclusion, we provide the first evidence on the association between maternal genetic susceptibility to unfavorable lipid profiles and fetal growth. Even in healthy, non-obese pregnant women, we observed associations between lipid trait genetic risk scores that appear to vary by maternal race/ethnicity and by offspring sex. With the exception of LDLc, these genetic risks remained unchanged after adjustment for early pregnancy circulating lipid levels.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

GRS and fetal weight (FW) associations vary by race/ethnicity, BMI and fetal sex

GRSTG was associated with increased FW in normal-weight Whites and obese Blacks

GRSHDLc increased FW in normal-weight Whites and Asians but decreased in Hispanics

GRSTChol was associated with increased FW in males and decreased in females

Results suggests that the GRSLDLc may operate by modulating circulating LDLc

Acknowledgement:

We thank research teams at all participating clinical centers (which include Christina Care Health Systems, Columbia University, Fountain Valley Hospital, California, Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, New York Hospital, Queens, Northwestern University, University of Alabama at Birmingham, University of California, Irvine, Medical University of South Carolina, Saint Peters University Hospital, Tufts University, and Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island). This work utilized the computational resources of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster (http://hpc.nih.gov).

Funding Sources: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health including American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funding via contract numbers HHSN275200800013C; HHSN275200800002I; HHSN27500006; HHSN275200800003IC; HHSN275200800014C; HHSN275200800012C; HHSN275200800028C; HHSN275201000009C and HHSN27500008. Additional support was obtained from the NIH Office of the Director and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None.

Reference

- 1.Barker D, The intrauterine origins of cardiovascular disease. Acta Paediatrica, 1993. 82: p. 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vrijkotte TG, et al. , Maternal triglyceride levels during early pregnancy are associated with birth weight and postnatal growth. J Pediatr, 2011. 159(5): p. 736–742 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clausen T, et al. , Maternal anthropometric and metabolic factors in the first half of pregnancy and risk of neonatal macrosomia in term pregnancies. A prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol, 2005. 153(6): p. 887–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitajima M, et al. , Maternal serum triglyceride at 24--32 weeks’ gestation and newborn weight in nondiabetic women with positive diabetic screens. Obstet Gynecol, 2001. 97(5 Pt 1): p. 776–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, et al. , Association of maternal serum lipids at late gestation with the risk of neonatal macrosomia in women without diabetes mellitus. Lipids Health Dis, 2018. 17(1): p. 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaumont RN, et al. , Genome-wide association study of offspring birth weight in 86 577 women identifies five novel loci and highlights maternal genetic effects that are independent of fetal genetics. Hum Mol Genet, 2018. 27(4): p. 742–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kathiresan S, et al. , A genome-wide association study for blood lipid phenotypes in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet, 2007. 8 Suppl 1: p. S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabatti C, et al. , Genome-wide association analysis of metabolic traits in a birth cohort from a founder population. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(1): p. 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He L, et al. , Pleiotropic Meta-Analyses of Longitudinal Studies Discover Novel Genetic Variants Associated with Age-Related Diseases. Front Genet, 2016. 7: p. 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraja AT, et al. , A bivariate genome-wide approach to metabolic syndrome: STAMPEED consortium. Diabetes, 2011. 60(4): p. 1329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabano S, et al. , Placental LPL gene expression is increased in severe intrauterine growth-restricted pregnancies. Pediatr Res, 2006. 59(2): p. 250–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs MB, et al. , Maternal apolipoprotein E genotype as a potential risk factor for poor birth outcomes: The Bogalusa Heart Study. J Perinatol, 2016. 36(6): p. 432–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y and Qi L, Diet and lifestyle interventions on lipids: combination with genomics and metabolomics. Clinical Lipidology, 2014. 9(4): p. 417–427. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ordovas JM, Gene-diet interaction and plasma lipid response to dietary intervention. Curr Atheroscler Rep, 2001. 3(3): p. 200–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann TJ, et al. , A large electronic-health-record-based genome-wide study of serum lipids. Nat Genet, 2018. 50(3): p. 401–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahratian A, et al. , Prepregnancy body mass index and gestational age-dependent changes in lipid levels during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol, 2010. 116(1): p. 107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozkurt L, et al. , The impact of preconceptional obesity on trajectories of maternal lipids during gestation. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 29971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirschmugl B, et al. , Maternal obesity modulates intracellular lipid turnover in the human term placenta. Int J Obes (Lond), 2017. 41(2): p. 317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geraghty AA, et al. , Maternal and fetal blood lipid concentrations during pregnancy differ by maternal body mass index: findings from the ROLO study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2017. 17(1): p. 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmisano BT, et al. , Sex differences in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Mol Metab, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teslovich TM, et al. , Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature, 2010. 466(7307): p. 707–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willer CJ, et al. , Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet, 2013. 45(11): p. 1274–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grewal J, et al. , Cohort Profile: NICHD Fetal Growth Studies-Singletons and Twins. Int J Epidemiol, 2018. 47(1): p. 25–25l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buck Louis GM, et al. , Racial/ethnic standards for fetal growth: the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2015. 213(4): p. 449 e1–449 e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das S, et al. , Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet, 2016. 48(10): p. 1284–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loh PR, et al. , Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. Nature Genetics, 2016. 48(11): p. 1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchsberger C, Abecasis GR, and Hinds DA, minimac2: faster genotype imputation. Bioinformatics, 2015. 31(5): p. 782–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genomes Project C, et al. , A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 2015. 526(7571): p. 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao W, et al. , Plasma concentrations of lipids during pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal study. J Diabetes, 2018. 10(6): p. 487–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, and Fredrickson DS, Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem, 1972. 18(6): p. 499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hediger ML, et al. , Ultrasound Quality Assurance for Singletons in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies. J Ultrasound Med, 2016. 35(8): p. 1725–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs KM and D’Alton M, 23: Can sonographer education and image review standardize image acquisition and caliper placement in 2D ultrasounds? Experience from the NICHD Fetal Growth Study. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2012. 206(1): p. S15–S16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadlock FP, et al. , Estimation of fetal weight with the use of head, body, and femur measurements--a prospective study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 1985. 151: p. 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duryea EL, et al. , A revised birth weight reference for the United States. Obstet Gynecol, 2014. 124(1): p. 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lander E and Schork N, Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science, 1994. 265: p. 2037–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price AL, et al. , Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet, 2006. 38(8): p. 904–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang CC, et al. , Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience, 2015. 4: p. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benowitz NL, et al. , Optimal serum cotinine levels for distinguishing cigarette smokers and nonsmokers within different racial/ethnic groups in the United States between 1999 and 2004. Am J Epidemiol, 2009. 169(2): p. 236–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng W, et al. , Changes in Serum Lipid Levels During Pregnancy and Association With Neonatal Outcomes: A Large Cohort Study. Reprod Sci, 2018: p. 1933719117746785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sattar N, et al. , Lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1999. 84(1): p. 128–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shungin D, et al. , New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature, 2015. 518(7538): p. 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dehghan A, et al. , Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation, 2011. 123(7): p. 731–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ligthart S, et al. , Bivariate genome-wide association study identifies novel pleiotropic loci for lipids and inflammation. BMC Genomics, 2016. 17: p. 443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teumer A, et al. , Genomewide meta-analysis identifies loci associated with IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels with impact on age-related traits. Aging Cell, 2016. 15(5): p. 811–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutaj P, Wender-Ozegowska E, and Brazert J, Maternal lipids associated with large-forgestational-age birth weight in women with type 1 diabetes: results from a prospective single-center study. Arch Med Sci, 2017. 13(4): p. 753–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farias DR, et al. , Maternal lipids and leptin concentrations are associated with large-forgestational-age births: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin WY, et al. , Associations between maternal lipid profile and pregnancy complications and perinatal outcomes: a population-based study from China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2016. 16: p. 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tekola-Ayele F, Workalemahu T, and Amare AT, High burden of birthweight-lowering genetic variants in Africans and Asians. BMC Med, 2018. 16(1): p. 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dumitrescu L, et al. , Genetic determinants of lipid traits in diverse populations from the population architecture using genomics and epidemiology (PAGE) study. PLoS Genet, 2011. 7(6): p. e1002138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bugatto F, et al. , Prepregnancy body mass index influences lipid oxidation rate during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2017. 96(2): p. 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toleikyte I, et al. , Pregnancy outcomes in familial hypercholesterolemia: a registry-based study. Circulation, 2011. 124(15): p. 1606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vrijkotte TG, et al. , Maternal lipid profile during early pregnancy and pregnancy complications and outcomes: the ABCD study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2012. 97(11): p. 3917–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zore T, Palafox M, and Reue K, Sex differences in obesity, lipid metabolism, and inflammation-A role for the sex chromosomes? Mol Metab, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Link JC and Reue K, Genetic Basis for Sex Differences in Obesity and Lipid Metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr, 2017. 37: p. 225–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Dongen J, et al. , Heritability of metabolic syndrome traits in a large population-based sample. J Lipid Res, 2013. 54(10): p. 2914–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Metrustry SJ, et al. , Variants close to NTRK2 gene are associated with birth weight in female twins. Twin Res Hum Genet, 2014. 17(4): p. 254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Catalano PM, Drago NM, and Amini SB, Factors affecting fetal growth and body composition. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1995. 172(5): p. 1459–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Zegher F, et al. , Androgens and fetal growth. Horm Res, 1998. 50(4): p. 243–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barbour LA and Hernandez TL, Maternal Non-glycemic Contributors to Fetal Growth in Obesity and Gestational Diabetes: Spotlight on Lipids. Curr Diab Rep, 2018. 18(6): p. 37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin AR, et al. , Human Demographic History Impacts Genetic Risk Prediction across Diverse Populations. Am J Hum Genet, 2017. 100(4): p. 635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.