Abstract

Background

Childhood maltreatment is associated with eating disorders, but types of childhood maltreatment often co-occur.

Objective

To examine associations between childhood maltreatment patterns and eating disorder symptoms in young adulthood.

Participants and Setting

Data came from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (N=14,322).

Method

Latent class analysis was conducted, using childhood physical neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse as model indicators. Logistic regression models adjusted for demographic covariates were conducted to examine associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms.

Results

In this nationally representative sample of U.S. young adults (mean age=21.82 years), 7.3% of participants reported binge eating-related concerns, 3.8% reported compensatory behaviors, and 8.6% reported fasting/skipping meals. Five childhood maltreatment latent classes emerged: “no/low maltreatment” (78.5% of the sample), “physical abuse only” (11.0% of the sample), “multi-type maltreatment” (7.8% of the sample), “physical neglect only” (2.1% of the sample), and “sexual abuse only” (0.6% of the sample). Compared to participants assigned to the “no/low maltreatment” class, participants assigned to the “multi-type maltreatment” class were more likely to report binge eating-related concerns (odds ratio=1.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.52, 2.56) and fasting/skipping meals (OR=1.85; 95% CI: 1.46, 2.34), and participants assigned to the “physical abuse only” class were more likely to report fasting/skipping meals (OR=1.35; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.76).

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that distinct childhood maltreatment profiles are differentially associated with eating disorder symptoms. Individuals exposed to multi-type childhood maltreatment may be at particularly high risk for eating disorders.

Keywords: Feeding and Eating Disorders, Child Abuse, Child Neglect, Young Adult

Introduction

Typical age of onset for eating disorders falls within adolescence and young adulthood (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Swanson, Crow, Le Grange, Swendsen, & Merikangas, 2011), and based on criteria for eating disorders in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), prevalence estimates of any eating disorder among young adults range from 1.2% - 2.9% for males and 5.7% - 15.2% for females (Allen, Byrne, Oddy, & Crosby, 2013; Smink, van Hoeken, Oldehinkel, & Hoek, 2014; Stice, Marti, & Rohde, 2013). Eating disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric disorders and strongly associated with medical complications, psychosocial impairment, and suicidality (Hudson et al., 2007; Mitchell & Crow, 2006; Swanson et al., 2011). Given their early age of onset, prevalence, and burden of disease, eating disorders are of significant public health concern. Even in the absence of meeting full diagnostic criteria, eating disorder symptoms – including cognitions and behaviors – are of concern given that they are associated with poor dietary intake (Larson, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story, 2009; Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, Story, & Perry, 2004), increased depressive symptoms (Ackard, Fulkerson, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2011; Hazzard, Hahn, Bauer, & Sonneville, 2019; Stice & Bearman, 2001), increased risk for full-threshold eating disorders (Fairburn, Cooper, Doll, & Davies, 2005; Stice, Gau, Rohde, & Shaw, 2017; Stice, Marti, & Durant, 2011), and suicidality (Crow, Eisenberg, Story, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2008; Kwan, Gordon, Carter, Minnich, & Grossman, 2017; Smith, Velkoff, Ribeiro, & Franklin, 2019; Veras, Ximenes, De Vasconcelos, & Sougey, 2017).

Childhood maltreatment, which encompasses various forms of childhood abuse and neglect, has been found to be associated with eating disorders (Afifi et al., 2017; Caslini et al., 2016; Molendijk, Hoek, Brewerton, & Elzinga, 2017), as well as with greater psychiatric comorbidity, greater treatment attrition, greater diagnostic crossover, and lower rates of full recovery among eating disorder patients (Castellini et al., 2018). Although there is convincing evidence that childhood maltreatment plays an important role in the development and clinical course of eating disorders, types of childhood maltreatment often co-occur (Higgins & McCabe, 2001), and it is not well understood how distinct childhood maltreatment patterns shape eating disorder risk.

Childhood maltreatment is common. In the United States, a developed country with high income inequality (Lobmayer & Wilkinson, 2000), more than one-third of children are estimated to experience any maltreatment by a caregiver before 18 years of age (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2015; Kim, Wildeman, Jonson-Reid, & Drake, 2017). Among individuals with a history of any childhood maltreatment, prevalence estimates of multi-type childhood maltreatment (i.e., experiencing more than one type of childhood maltreatment) range from 35% in community samples (Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, 2003) to 65% in samples identified through Child Protective Services case records (Kim, Mennen, & Trickett, 2017). Because types of childhood maltreatment often co-occur, examining types of childhood maltreatment in isolation may overestimate the unique associations between each individual type of childhood maltreatment and health outcomes (Armour, Elklit, & Christoffersen, 2014; Pears, Kim, & Fisher, 2008). Illustrating this idea, Afifi et al. (2017) found physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse to be associated with binge eating disorder among women when examining each type of childhood maltreatment in isolation, but only associations for sexual abuse and emotional abuse held when controlling for all types of childhood maltreatment. Additionally, growing evidence suggests that distinct childhood maltreatment profiles (e.g., exposure to physical abuse and sexual abuse versus exposure to physical abuse and physical neglect) have qualitatively different associations with health outcomes (Berzenski & Yates, 2011; Curran, Adamson, Stringer, Rosato, & Leavey, 2016). Thus, taking a person-centered approach (Von Eye & Bergman, 2003) that advances understanding of how specific patterns of childhood maltreatment shape eating disorder risk could help inform interventions to treat and prevent eating disorders.

While preventing childhood maltreatment from occurring in the first place is of utmost importance, current childhood maltreatment prevention efforts have limited reach. Thus, we must also develop ways to mitigate the consequences of childhood maltreatment once it has occurred. Childhood maltreatment is associated with low self-esteem (Greger, Myhre, Klöckner, & Jozefiak, 2017; Ju & Lee, 2018), and low self-esteem has been found to mediate pathways from childhood maltreatment to general psychopathology and well-being (Greger et al., 2017). Low self-esteem is also associated with eating disorder symptoms (Bardone-Cone, Thompson, & Miller, 2018); thus, low self-esteem may be a mediator in the pathway from childhood maltreatment to eating disorder symptoms. Improving self-esteem may be a way to mitigate the consequences of childhood maltreatment once it has occurred, as low self-esteem is modifiable (Haney & Durlak, 1998). Adolescence is a key developmental period for the formation of self-esteem (Robins & Trzesniewski, 2005), and, as such, could be an important developmental period to target for intervention. If self-esteem in adolescence mediates associations between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder symptoms, eating disorders treatment and prevention efforts for individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment could focus on improving self-esteem in adolescence.

Using a person-centered approach and data from a large, nationally representative sample of young adults in the United States, the objectives of this study were to (a) identify distinct childhood maltreatment profiles, (b) examine associations between childhood maltreatment profiles and eating disorder symptoms in young adulthood, and, if such associations exist, (c) assess the extent to which self-esteem in adolescence mediates such associations.

Methods

Participants

This study used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health; Harris, 2009). Systematic sampling methods and implicit stratification were incorporated into the Add Health study design to ensure the sample was representative of U.S. schools with respect to region of country, urbanicity, school size, school type, and ethnicity. Wave I data were collected in 1994–1995 when participants were in grades 7–12, Wave II data were collected in 1996 when participants were in grades 8–12, and Wave III data were collected in 2001–2002 when participants were 18–26 years old (Harris et al., 2009). Data were collected via in-home interviews and recorded on laptop computers. For less sensitive topics, interviewers read the questions aloud and entered participants’ answers. For more sensitive topics, participants entered their own answers in privacy. Of the 15,197 participants interviewed at Wave III, 875 participants were excluded due to missing sampling weights, leaving 14,322 participants available for analyses in the present study. The Add Health protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Harris et al., 2009).

Measures

Childhood maltreatment

Childhood maltreatment was assessed retrospectively at Wave III using Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (Harris et al., 2009), a method that has been shown to elicit more accurate reporting than interviewer-administered assessment for questions of a sensitive nature (Metzger et al., 2000). Participants were asked about the following occurrences prior to sixth grade: “How often had your parents or other adult care-givers slapped, hit, or kicked you?” (physical abuse), “How often had your parents or other adult care-givers not taken care of your basic needs, such as keeping you clean or providing food or clothing?” (physical neglect), and “How often had one of your parents or other adult care-givers touched you in a sexual way, forced you to touch him or her in a sexual way, or forced you to have sexual relations?” (sexual abuse). Possible response options for each question were one time, two times, three to five times, six to ten times, more than ten times, and this has never happened.

Eating disorder symptoms in young adulthood

Eating disorder symptoms were assessed at Wave III via self-report. Participants reporting that they had “eaten so much in a short period that [they] would have been embarrassed if others had seen [them] do it” and/or “been afraid to start eating because [they] thought [they] wouldn’t be able to stop or control [their] eating” in the past seven days were assigned a positive response for the dichotomous variable for binge eating-related concerns. Participants reporting that they “made [themselves] throw up,” “took laxatives,” “took weight-loss pills,” and/or “used diuretics – that is, water pills” in the past seven days in order to lose weight or stay the same weight were assigned a positive response for the dichotomous variable for compensatory behaviors. Participants reporting that they “fasted or skipped meals” in the past seven days in order to lose weight or stay the same weight were assigned a positive response for the dichotomous variable for fasting/skipping meals.

Self-esteem in adolescence

Self-esteem was assessed at Waves I and II with six items modified from or similar to items in the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a measure of global self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965). A five-point agreement scale was used for the following items: “You have a lot of good qualities,” “You have a lot to be proud of,” “You like yourself just the way you are,” “You feel like you are doing everything just about right,” “You feel socially accepted,” and “You feel loved and wanted.” These items have previously been found to represent a unidimensional construct of self-esteem (Shrier, Harris, Sternberg, & Beardslee, 2001). Wave I data were used for participants with complete data at Wave I; Wave II data were used for participants with missing data at Wave I but complete data at Wave II. We averaged responses to yield a continuous variable with possible scores ranging from 1–5, with higher scores indicating lower levels of self-esteem (Cronbach’s α=.84 in this sample).

Demographic covariates

The following variables were included as demographic covariates: age at Wave III (continuous), sex (dichotomous), race/ethnicity (categorical: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or other), highest parental education (categorical: less than high school, high school graduate or equivalent, some college/trade school, or graduated college or above), and percent federal poverty level (FPL) in adolescence (continuous; calculated using parent-reported household income in 1994, participant-reported household size during adolescence, and 1994 federal poverty guidelines).

Statistical analysis

All analyses accounted for the complex sampling design used in Add Health, and all analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 unless otherwise noted.

Descriptive statistics

We computed univariate statistics for childhood maltreatment, eating disorder symptoms, self-esteem, and demographic covariates. We also computed bivariate statistics for these variables by sex.

Latent class analysis

We utilized latent class analysis (LCA) to identify distinct childhood maltreatment profiles. LCA is a person-centered approach (Von Eye & Bergman, 2003) that has facilitated important insights regarding eating disorders classification (Peterson et al., 2011; Swanson et al., 2014) and childhood maltreatment patterns (Brumley, Brumley, & Jaffee, 2019; Debowska, Willmott, Boduszek, & Jones, 2017; Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch, Manly, & Cicchetti, 2019). Accounting for the complex sampling design, we conducted LCA with ordinal categorical childhood maltreatment variables (physical abuse, physical neglect, and sexual abuse) as indicators. Using the six observed levels of ordinal categorical responses for each type of maltreatment resulted in an unwieldy number of latent classes that were difficult to interpret; therefore, in order to identify meaningful latent classes, we collapsed response options for each type of childhood maltreatment to having never occurred, having occurred one or two times, or having occurred three or more times. Minimum Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978) was used to determine which number of classes provided the optimal balance between model fit and parsimony, as BIC has been shown to outperform other information criteria in LCA model selection (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). For comparison, we also reported Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987). After identifying the model providing the optimal balance between model fit and parsimony, each participant was assigned to a latent class based on maximum posterior probability. We conducted LCA with Latent GOLD 5.1. We then computed bivariate descriptive statistics by childhood maltreatment latent classes for eating disorder symptoms, self-esteem, and demographic covariates.

Multiple imputation

Data were missing at the following rates: 25% for percent FPL, 7% for childhood maltreatment latent class membership, 5% for highest parental education, and less than 1% for eating disorder symptoms, self-esteem, age, sex, and race/ethnicity. To preserve sample size, we conducted multiple imputation with the assumption that data were missing at random. We created 20 imputed datasets using the fully conditional specification method in the MI procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2015). In sensitivity analyses, we conducted analyses with only demographic covariates imputed and using complete cases only.

Logistic regression

We ran logistic regression models examining associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms, adjusted for demographic covariates. We ran separate models for binge eating-related concerns, compensatory behaviors, and fasting/skipping meals. Because sex differences in associations between childhood maltreatment and eating disorders have been observed (Afifi et al., 2017), we assessed for effect modification by sex by adding cross-product terms (childhood maltreatment latent class x sex) to the models.

Combining inference from multiply imputed datasets

Results from logistic regression analyses were combined and summarized, using both within-imputation and between-imputation variance to reflect uncertainty due to the missing data (Little & Rubin, 2002).

Mediation analysis

To assess for mediation by self-esteem in adolescence, we ran the logistic regression models described above additionally adjusting for self-esteem in adolescence, and we ran a linear regression model examining associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and self-esteem in adolescence, adjusted for demographic covariates. For observed associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms, we used the results from these models to calculate the proportion mediated by self-esteem in adolescence using the approach described by Vanderweele and Vansteelandt (2010) for mediation analysis with dichotomous outcomes in a counterfactual framework. We obtained 95% confidence intervals via bootstrapping with 1,000 resamples.

Results

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. In this sample of young adults (mean age = 21.82 years), 7.3% of participants reported binge eating-related concerns, 3.8% of participants reported compensatory behaviors, and 8.6% of participants reported fasting/skipping meals. Childhood physical abuse was experienced one or two times by 13.9% of participants and three or more times by 14.5% of participants, childhood physical neglect was experienced one or two times by 6.7% of participants and three or more times by 5.0% of participants, and childhood sexual abuse was experienced one or two times by 2.8% of participants and three or more times by 1.7% of participants.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics, overall and by sex

| Overall | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 14,322) | (N = 6,759) | (N = 7,563) | ||

| Sampled Frequency (Weighted Percent) | P | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 7,728 (67.6) | 3,649 (67.3) | 4,079 (67.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 3,038 (16.0) | 1,323 (15.7) | 1,715 (16.3) | .38 |

| Other | 3,514 (16.4) | 1,761 (17.0) | 1,753 (15.9) | |

| Percent federal poverty level | ||||

| < 100% | 1,783 (16.4) | 818 (16.0) | 965 (16.8) | |

| 100–199% | 2,340 (20.9) | 1,126 (21.1) | 1,214 (20.6) | .63 |

| 200–399% | 4,061 (38.1) | 1,958 (38.7) | 2,103 (37.5) | |

| ≥ 400% | 2,624 (24.7) | 1,257 (24.2) | 1,367 (25.1) | |

| Highest parental education | ||||

| Less than high school | 1,694 (12.0) | 751 (11.8) | 943 (12.2) | |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 3,974 (31.6) | 1,880 (31.5) 4 | 2,094 (31.6) | .23 |

| Some college/trade school | 2,875 (21.4) | 1,327 (20.6) | 1,548 (22.1) | |

| Graduated college or above | 5,083 (35.1) | 2,473 (36.1) | 2,610 (34.0) | |

| Childhood physical abuse | ||||

| 1–2 times | 1,943 (13.9) | 978 (14.8) | 965 (13.0) | .03 |

| 3 or more times | 2,053 (14.5) | 1,020 (15.0) | 1,033 (14.0) | |

| Childhood physical neglect | ||||

| 1–2 times | 882 (6.7) | 527 (8.7) | 355 (4.6) | <.001 |

| 3 or more times | 676 (5.0) | 368 (5.9) | 308 (4.1) | |

| Childhood sexual abuse | ||||

| 1–2 times | 403 (2.8) | 210 (3.4) | 193 (2.3) | <.001 |

| 3 or more times | 242 (1.7) | 69 (1.1) | 173 (2.3) | |

| Binge eating-related concerns | 1,095 (7.3) | 427 (5.9) | 668 (8.8) | <.001 |

| Compensatory behaviors | 591 (3.8) | 118 (1.6) | 473 (6.0) | <.001 |

| Fasting/skipping meals | 1,303 (8.6) | 390 (5.2) | 913 (12.2) | <.001 |

| Mean (Standard Error) | p | |||

| Age (years) | 21.82 (0.12) | 21.91 (0.12) | 21.73 (0.12) | <.001 |

| Self-esteem in adolescence | 1.89 (0.01) | 1.79 (0.01) | 1.98 (0.01) | <.001 |

Higher self-esteem scores indicate lower levels of self-esteem.

Latent class analysis

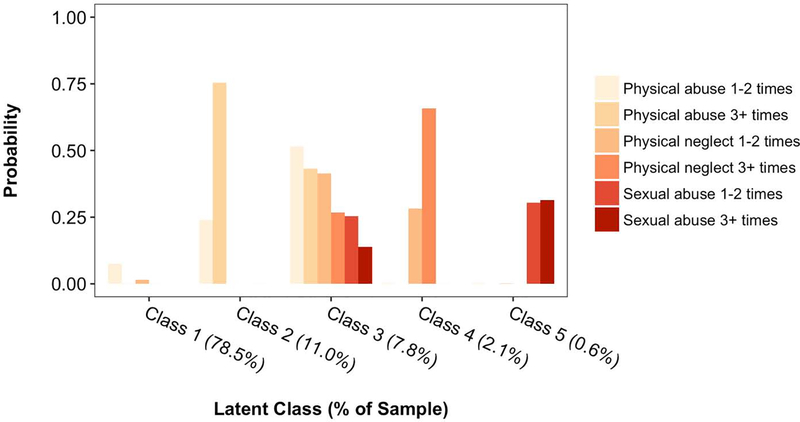

LCA model fit indices are presented in Table 2. Both BIC and AIC were lowest for a five-class model, indicating that this model provided the optimal balance between model fit and parsimony. Probability estimates of each type of childhood maltreatment for each latent class are displayed in Figure 1. Class 1 was characterized by low probability of childhood maltreatment (“no/low maltreatment”) and comprised 78.5% of the sample, Class 2 was characterized by high probability of childhood physical abuse only (“physical abuse only”) and comprised 11.0% of the sample, Class 3 was characterized by high probability of each childhood maltreatment type (“multi-type maltreatment”) and comprised 7.8% of the sample, Class 4 was characterized by high probability of childhood physical neglect only (“physical neglect only”) and comprised 2.1% of the sample, and Class 5 was characterized by high probability of childhood sexual abuse only (“sexual abuse only”) and comprised 0.6% of the sample.

Table 2.

Model fit indices for childhood maltreatment latent class analysis

| BIC | AIC | |

|---|---|---|

| 1-class model | 58,586,069.60 | 58,585,980.57 |

| 2-class model | 56,000,066.97 | 55,999,918.59 |

| 3-class model | 55,522,768.51 | 55,522,560.78 |

| 4-class model | 55,143,193.93 | 55,142,926.84 |

| 5-class model | 55,012,346.82 | 55,012,020.38 |

| 6-class model | 55,013,689.81 | 55,013,304.02 |

BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion. Lower BIC and AIC values indicate better model fit. Models with ≥ 7 classes were not identified. Bold indicates optimal balance between model fit and parsimony.

Figure 1.

Probability estimates of each type of childhood maltreatment for each latent class

Bivariate descriptive statistics by childhood maltreatment latent classes are presented in Table 3. With the exception of compensatory behaviors, all variables examined differed between latent classes (age: p = .01; all other variables: p < .001).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics by childhood maltreatment latent classes.

| “No/Low Maltreatment” Class | “Physical Abuse Only” Class | “Multi-Type Maltreatment” Class | “Physical Neglect Only” Class | “Sexual Abuse Only” Class | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10,322) | (N = 1,499) | (N = 1,085) | (N = 271) | (N = 89) | ||

| Sampled Frequency (Weighted Percent) | P | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4,647 (48.7) | 762 (53.5) | 578 (57.3) | 142 (56.8) | 11 (15.5) | <.001 |

| Female | 5,675 (51.3) | 737 (46.5) | 507 (42.7) | 129 (43.2) | 78 (84.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 5,856 (70.2) | 764 (64.8) | 489 (56.7) | 124 (59.1) | 48 (66.9) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2,142 (15.3) | 285 (14.1) | 263 (21.8) | 70 (19.7) | 20 (18.7) | <.001 |

| Other | 2,293 (14.5) | 446 (21.2) | 331 (21.5) | 77 (21.1) | 20 (14.4) | |

| Percent federal poverty level | ||||||

| < 100% | 1,174 (14.7) | 166 (15.3) | 204 (26.7) | 48 (20.6) | 16 (20.1) | |

| 100–199% | 1,606 (19.6) | 243 (21.1) | 209 (26.5) | 58 (29.5) | 24 (29.2) | <.001 |

| 200–399% | 3,018 (39.6) | 488 (41.2) | 248 (30.5) | 57 (29.4) | 18 (32.1) | |

| ≥ 400% | 2,040 (26.1) | 251 (22.4) | 128 (16.4) | 38 (20.4) | 10 (18.6) | |

| Highest parental education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 1,127 (11.0) | 159 (11.0) | 184 (19.1) | 46 (17.7) | 12 (7.4) | |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 2,791 (30.4) | 382 (30.7) | 336 (35.4) | 101 (44.7) | 34 (49.7) | <.001 |

| Some college/trade school | 2,060 (21.4) | 357 (25.3) | 214 (21.2) | 45 (15.3) | 17 (18.3) | |

| Graduated college or above | 3,893 (37.2) | 541 (32.9) | 267 (24.2) | 64 (22.3) | 20 (24.6) | |

| Binge eating-related concerns | 711 (6.7) | 128 (7.3) | 138 (12.9) | 28 (9.5) | 11 (16.3) | <.001 |

| Compensatory behaviors | 410 (3.9) | 74 (4.5) | 55 (4.1) | 11 (3.1) | 9 (9.3) | .28 |

| Fasting/skipping meals | 873 (8.0) | 148 (10.0) | 141 (13.5) | 27 (8.4) | 8 (7.0) | <.001 |

| Mean (Standard Error) | P | |||||

| Age (years) | 21.80 (0.12) | 22.08 (0.13) | 21.84 (0.15) | 21.56 (0.21) | 21.84 (0.28) | .01 |

| Self-esteem in adolescence | 1.86 (0.01) | 1.97 (0.02) | 1.99 (0.02) | 1.77 (0.05) | 2.05 (0.09) | <.001 |

Higher self-esteem scores indicate lower levels of self-esteem.

Associations between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder symptoms

Associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms are presented in Table 4. After adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, highest parental education, and percent federal poverty level in adolescence, participants assigned to Class 3 (“multi-type maltreatment”) had 1.97 times greater odds of reporting binge eating-related concerns (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.52, 2.56) and 1.85 times greater odds of reporting fasting/skipping meals (95% CI: 1.46, 2.34) than those assigned to Class 1 (“no/low maltreatment”), and participants assigned to Class 2 (“physical abuse only”) had 1.35 times greater odds of reporting fasting/skipping meals (95% CI: 1.04, 1.76) than those assigned to Class 1 (“no/low maltreatment”). No other statistically significant associations were observed.

Table 4.

Associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms in young adulthood

| Binge Eating-Related Concerns | Compensatory Behaviors | Fasting/ Skipping Meals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | |||

| Class 1 (“no/low maltreatment”) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Class 2 (“physical abuse only”) | 1.11 (0.84, 1.45) | 1.14 (0.84, 1.56) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.76)* |

| Class 3 (“multi-type maltreatment”) | 1.97 (1.52, 2.56)*** | 1.12 (0.73, 1.71) | 1.85 (1.46, 2.34)*** |

| Class 4 (“physical neglect only”) | 1.47 (0.85, 2.52) | 0.72 (0.33, 1.58) | 1.09 (0.65, 1.81) |

| Class 5 (“sexual abuse only”) | 2.08 (0.92, 4.70) | 1.59 (0.62, 4.04) | 0.65 (0.25, 1.67) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, highest parental education, and percent federal poverty level in adolescence.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

The proportion of the association between the “multi-type maltreatment” class and binge eating-related concerns mediated by self-esteem in adolescence was 6.9% (95% CI: 6.0%, 8.7%), and the proportion of the association between the “multi-type maltreatment” class and fasting/skipping meals mediated by self-esteem in adolescence was 12.0% (95% CI: 10.9%, 14.7%). The proportion of the association between the “physical abuse only” class and fasting/skipping meals mediated by self-esteem in adolescence was 15.7%, but this proportion was not statistically significant (95% CI: −5.9%, 73.2%).

There was no evidence of effect modification by sex for binge eating-related concerns (cross-product p = .42) or fasting/skipping meals (cross-product p = .94). There was evidence of effect modification by sex for compensatory behaviors (cross-product p < .001); however, sex-stratified results suggested this was an artifact of having zero males reporting compensatory behaviors assigned to the “sexual abuse only” class.

Results were not substantially different in sensitivity analyses using complete cases only and imputing only demographic covariates, with the exception that when imputing only demographic covariates, participants assigned to Class 5 (“sexual abuse only”) were 2.37 times more likely to report binge eating-related concerns (95% CI: 1.04, 5.39) than those assigned to Class 1 (“no/low maltreatment”).

Discussion

The aims of this study were to identify distinct childhood maltreatment classes via latent class analysis based on the occurrence of physical abuse, physical neglect, and sexual abuse in childhood, to examine associations between childhood maltreatment classes and eating disorder symptoms in young adulthood, as well as to assess the extent to which self-esteem in adolescence mediates such associations. We identified five childhood maltreatment classes: “no/low maltreatment,” “physical abuse only,” “multi-type maltreatment,” “physical neglect only,” and “sexual abuse only.” Participants assigned to the “multi-type maltreatment” class were more likely to report binge eating-related concerns and fasting/skipping meals compared to those assigned to the “no/low maltreatment” class, and self-esteem in adolescence mediated statistically significant but modest proportions of these associations. Participants assigned to the “physical abuse only” class were also more likely to report fasting/skipping meals compared to those assigned to the “no/low maltreatment” class. However, we did not observe any other statistically significant associations between single-type childhood maltreatment classes and eating disorder symptoms. These findings highlight the importance of considering the overall childhood maltreatment profile rather than focusing on individual types of childhood maltreatment.

Over 1,000 participants (7.8% of the sample) in this study were assigned to the “multi-type maltreatment” class, supporting previous findings that different types of childhood maltreatment often co-occur (Edwards et al., 2003; Higgins & McCabe, 2001; Kim et al., 2017). Our results suggest that exposure to multiple types of childhood maltreatment may increase risk for eating disorder symptoms, whereas exposure to isolated types of childhood maltreatment generally may not. Comparing across types of eating disorder symptoms, we observed similar associations for the “multi-type maltreatment” class with binge eating-related concerns and fasting/skipping meals, but we did not observe an association for compensatory behaviors. This null result may reflect a true lack of association, or it may reflect heterogeneity in the way we defined compensatory behaviors. Due to small numbers of participants reporting each individual type of compensatory behavior, we collapsed four heterogenous types of compensatory behaviors (vomiting, using laxatives, using weight-loss pills, and using diuretics) into one variable.

With regard to single-type childhood maltreatment classes, although we did not observe statistically significant associations with eating disorder symptoms except between the “physical abuse only” class and fasting/skipping meals, we observed some differences in direction of association across eating disorder symptoms. The most striking difference was for the “sexual abuse only” class. While associations were not statistically significant, estimates suggested that compared to participants assigned to the “no/low maltreatment” class, participants assigned to the “sexual abuse only” class had over twice the odds of reporting binge eating-related concerns but 35% lower odds of reporting fasting/skipping meals. The direction of the estimate for binge eating-related concerns is consistent with previous research linking childhood sexual abuse with binge eating (Van Gerko, Hughes, Hamill, & Waller, 2005; Wonderlich, Wilsnack, Wilsnack, & Harris, 1996), but to our knowledge, no previous studies have found lower dietary restraint or restriction among individuals with a history of childhood sexual abuse.

Our results suggesting that exposure to multiple types of childhood maltreatment may increase risk for eating disorder symptoms cohere with previous findings in the broader mental health literature that individuals with a history of multi-type childhood maltreatment, but not single-type childhood maltreatment, have greater depressive symptoms and suicidality than individuals with no history of childhood maltreatment (Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O’Farrill-Swails, 2005). Multi-type childhood maltreatment may confer greater risk for adverse mental health outcomes than single-type childhood maltreatment not only because of the cumulative effects of the multiple types of maltreatment, but also because multi-type childhood maltreatment may be a marker of a more adverse home environment overall. For instance, exposure to more types of childhood maltreatment has been found to be associated with lower caretaker functioning and greater domestic violence in the home (Kim et al., 2017). However, other studies have found dose-response relationships between the number of types of childhood maltreatment reported and adverse mental health outcomes, such that individuals reporting single-type childhood maltreatment were more likely to have adverse mental health outcomes than their non-maltreated counterparts (Edwards et al., 2003). Thus, single-type childhood maltreatment also has detrimental consequences, but the detrimental consequences may not be as severe or may manifest in different ways. Taking a person-centered approach enables us to gain insight as to how detrimental consequences may manifest differently across unique childhood maltreatment profiles.

Self-esteem in adolescence did not emerge as a salient factor driving the observed associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms. Although it mediated statistically significant proportions of observed associations for the “multi-type maltreatment” class, the proportions were modest, which may be related to the fact that low self-esteem is a somewhat non-specific risk factor for a broad range of adverse mental health outcomes (Mann, Hosman, Schaalma, & de Vries, 2004). The non-specificity of low self-esteem as a risk factor may make it a less potent mediator on the pathway from childhood maltreatment to eating disorder symptoms. Nevertheless, the non-specific nature of self-esteem suggests that self-esteem may be important to consider in transdiagnostic efforts, as interventions targeting self-esteem have been found to not only improve self-esteem, but also reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (Musiat et al., 2014; Tirlea, Truby, & Haines, 2016). Future studies should examine other potential mediators that could be more specific to eating disorder-related outcomes, such as dissociation and impulsivity.

This study had several strengths. We used data from a large, nationally representative sample of young adults in the United States. Using a community sample rather than a clinical sample avoids bias introduced by studying treatment-seeking individuals, and young adulthood is a critical period, as levels of cognitive features of eating disorders such as body dissatisfaction have been found to increase during this period (Slane, Klump, McGue, & Iacono, 2014). Additionally, our sample included males, a group that has been severely underrepresented in research examining associations between childhood maltreatment and eating disorders (Caslini et al., 2016). We did not find evidence for differences by sex, highlighting the importance of including males in this area of research. Further, using LCA allowed us to efficiently address the interrelatedness yet distinct qualities of multiple types of childhood maltreatment, harnessing a person-centered approach to foster better understanding of pathways from childhood maltreatment to eating disorder symptoms.

Despite these strengths, this study also had limitations, which included the retrospective self-report of childhood maltreatment and the use of single-item measures with a seven-day assessment time frame to assess eating disorder symptoms. Another limitation was the narrow range of childhood maltreatment types that were assessed (e.g., emotional abuse and neglect were not assessed). Additionally, residual confounding is a possibility, and latent class assignment does not convey the probabilistic nature of the latent class model. Not accounting for the uncertainty in class assignment can lead to underestimation of standard errors in logistic regression. Despite these limitations, findings from this study offer important contributions to understanding the relationship between childhood maltreatment and eating disorders.

The findings from this study provide evidence for the existence of distinct childhood maltreatment profiles that are differentially associated with eating disorder symptoms. Although the current study focused on eating disorders, which are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality (Hudson et al., 2007; Mitchell & Crow, 2006; Swanson et al., 2011), individuals exposed to multiple types of childhood maltreatment are also at high risk for adverse mental health outcomes across multiple domains, including internalizing (e.g., depression, anxiety) and externalizing disorders (e.g., aggression, delinquency; Debowska et al., 2017). Accurately classifying childhood maltreatment profiles, as we did in the current study, is therefore not only valuable for identifying high-risk subgroups with regard to eating disorders, but also a necessary step toward better informing treatment and prevention for those high-risk subgroups across a wide range of mental health outcomes. More research is needed to better understand how treatment and prevention approaches can best serve those high-risk subgroups. From a treatment perspective, future research could investigate how trauma-informed approaches (Brewerton, 2018; Trottier, Monson, Wonderlich, MacDonald, & Olmsted, 2017) may help effectively treat mental disorders among patients with a history of childhood maltreatment, as well as how the appropriate course of treatment may differ depending on the childhood maltreatment profile. From a prevention perspective, future research could explore how targeted prevention programs for individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment might maximize effectiveness by taking a personalized prevention approach for a range of mental health outcomes, providing tailored feedback based on risk profiling. In addition, ongoing research that uncovers modifiable mediators of the associations between childhood maltreatment and mental disorders and tests the efficacy of trauma-informed treatment approaches and targeted prevention programs are needed to help minimize the long-lasting consequences of childhood maltreatment and reduce the public health burden of mental disorders. Ultimately, however, we need to strengthen strategies to prevent childhood maltreatment – particularly multi-type maltreatment, given its pervasiveness and adverse impact across a wide range of domains – from occurring in the first place.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number T32 MH082761).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial conflicts relevant to this article to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2011). Psychological and behavioral risk profiles as they relate to eating disorder diagnoses and symptomatology among a school-based sample of youth. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(5), 440–446. 10.1002/eat.20846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, Sareen J, Fortier J, Taillieu T, Turner S, Cheung K, & Henriksen CA (2017). Child maltreatment and eating disorders among men and women in adulthood: Results from a nationally representative United States sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(11), 1281–1296. 10.1002/eat.22783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52(3), 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Allen KL, Byrne SM, Oddy WH, & Crosby RD (2013). DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 eating disorders in adolescents: Prevalence, stability, and psychosocial correlates in a population-based sample of male and female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(3), 720–732. 10.1037/a0034004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Feeding and Eating Disorders In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Association; [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, & O’Farrill-Swails L (2005). Single versus multi-type maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 11(4), 29–52. 10.1300/J146v11n04_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Elklit A, & Christoffersen MN (2014). A latent class analysis of childhood maltreatment: Identifying abuse typologies. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 19(1), 23–39. 10.1080/15325024.2012.734205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone-Cone AM, Thompson KA, & Miller AJ (2018). The self and eating disorders. Journal of Personality. 10.1111/jopy.12448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzenski SR, & Yates TM (2011). Classes and consequences of multiple maltreatment: A person-centered analysis. Child Maltreatment, 16(4), 250–261. 10.1177/1077559511428353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD (2018). An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 1–18. 10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brumley LD, Brumley BP, & Jaffee SR (2019). Comparing cumulative index and factor analytic approaches to measuring maltreatment in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2018.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caslini M, Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Dakanalis A, Clerici M, & Carrà G (2016). Disentangling the association between child abuse and eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(1), 79–90. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini G, Lelli L, Cassioli E, Ciampi E, Zamponi F, Campone B, … Ricca V (2018). Different outcomes, psychopathological features, and comorbidities in patients with eating disorders reporting childhood abuse: A 3-year follow-up study. European Eating Disorders Review. 10.1002/erv.2586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow S, Eisenberg ME, Story M, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2008). Are body dissatisfaction, eating disturbance, and body mass index predictors of suicidal behavior in adolescents? A longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 887–892. 10.1037/a0012783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran E, Adamson G, Stringer M, Rosato M, & Leavey G (2016). Severity of mental illness as a result of multiple childhood adversities: US National Epidemiologic Survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(5), 647–657. 10.1007/s00127-016-1198-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debowska A, Willmott D, Boduszek D, & Jones AD (2017). What do we know about child abuse and neglect patterns of co-occurrence? A systematic review of profiling studies and recommendations for future research. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 100–111. 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, & Anda RF (2003). Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1453–1460. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, & Davies BA (2005). Identifying dieters who will develop an eating disorder: a prospective, population-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(12), 2249–2255. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 746–754. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger HK, Myhre AK, Klöckner CA, & Jozefiak T (2017). Childhood maltreatment, psychopathology and well-being: The mediator role of global self-esteem, attachment difficulties and substance use. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 122–133. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney P, & Durlak JA (1998). Changing self-esteem in children and adolescents: A metaanalytical review. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(4), 423–433. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2704_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, & Udry JR (2009). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health: Research Design [WWW document]. Retrieved April 1, 2016, from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design

- Harris Kathleen Mullan. (2009). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), Waves I & II, 1994–1996; Wave III, 2001–2002; Wave IV, 2007–2009 [machine-readable data file and documentation]. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 10.3886/ICPSR27021.v9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazzard VM, Hahn SL, Bauer KW, & Sonneville KR (2019). Binge eating-related concerns and depressive symptoms in young adulthood: Seven-year longitudinal associations and differences by race/ethnicity. Eating Behaviors, 32, 90–94. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, & McCabe MP (2001). Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(6), 547–578. 10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00030-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, & Kessler RC (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju S, & Lee Y (2018). Developmental trajectories and longitudinal mediation effects of self-esteem, peer attachment, child maltreatment and depression on early adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 353–363. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Wildeman C, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B (2017). Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 274–280. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Mennen FE, & Trickett PK (2017). Patterns and correlates of co-occurrence among multiple types of child maltreatment. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 492–502. 10.1111/cfs.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MY, Gordon KH, Carter DL, Minnich AM, & Grossman SD (2017). An examination of the connections between eating disorder symptoms, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide risk among undergraduate students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 47(4), 493–508. 10.1111/sltb.12304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, & Story M (2009). Weight control behaviors and dietary intake among adolescents and young adults: Longitudinal findings from Project EAT. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(11), 1869–1877. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, & Rubin DB (2002). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data (2nd ed). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lobmayer P, & Wilkinson R (2000). Income, inequality and mortality in 14 developed countries. Sociology of Health and Illness, 22(4), 401–414. 10.1111/1467-9566.00211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mann M, Hosman CMH, Schaalma HP, & de Vries NK (2004). Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Education Research, 19(4), 357–372. 10.1093/her/cyg041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Koblin B, Turner C, Navaline H, Valenti F, Holte S, … Seage GR (2000). Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152(2), 99–106. 10.1093/aje/152.2.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, & Crow S (2006). Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(4), 438–443. 10.1097/01.yco.0000228768.79097.3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk ML, Hoek HW, Brewerton TD, & Elzinga BM (2017). Childhood maltreatment and eating disorder pathology: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(8), 1402–1416. 10.1017/S0033291716003561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musiat P, Conrod P, Treasure J, Tylee A, Williams C, & Schmidt U (2014). Targeted prevention of common mental health disorders in university students: Randomised controlled trial of a transdiagnostic trait-focused web-based intervention. PLoS ONE, 9(4), 1–10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0093621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M, & Perry CL (2004). Weight-control behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: Implications for dietary intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 104(6), 913–920. 10.1016/j.jada.2004.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Kim HK, & Fisher PA (2008). Psychosocial and cognitive functioning of children with specific profiles of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(10), 958–971. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Swanson SA, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, … Halmi KA (2011). Examining the stability of DSM-IV and empirically derived eating disorder classification: implications for DSM-5. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(6), 777–783. 10.1037/a0025941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, & Trzesniewski KH (2005). Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2015). The MI Procedure In SAS/STAT® 14.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. 10.1214/aos/1176344136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Harris SK, Sternberg M, & Beardslee WR (2001). Associations of depression, self-esteem, and substance use with sexual risk among adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 33(3), 179–189. 10.1006/pmed.2001.0869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slane JD, Klump KL, McGue M, & Iacono WG (2014). Developmental trajectories of disordered eating from early adolescence to young adulthood: a longitudinal study. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(7), 793–801. 10.1002/eat.22329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smink FRE, van Hoeken D, Oldehinkel AJ, & Hoek HW (2014). Prevalence and severity of DSM-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(6), 610–619. 10.1002/eat.22316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Velkoff EA, Ribeiro JD, & Franklin J (2019). Are eating disorders and related symptoms risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors? A meta-analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(1), 221–239. 10.1111/sltb.12427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, & Bearman SK (2001). Body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: a growth curve analysis. Developmental Psychology, 37(5), 597–607. 10.1037/0012-1649.37.5.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Gau JM, Rohde P, & Shaw H (2017). Risk factors that predict future onset of each DSM-5 eating disorder: Predictive specificity in high-risk adolescent females. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(1), 38 10.1037/abn0000219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, & Durant S (2011). Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: Evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(10), 622–627. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, & Rohde P (2013). Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(2), 445–457. 10.1037/a0030679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, & Merikangas KR (2011). Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 714–723. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SA, Horton NJ, Crosby RD, Micali N, Sonneville KR, Eddy K, & Field AE (2014). A latent class analysis to empirically describe eating disorders through developmental stages. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(7), 762–772. 10.1002/eat.22308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirlea L, Truby H, & Haines TP (2016). Pragmatic, randomized controlled trials of the Girls on the Go! Program to improve self-esteem in girls. American Journal of Health Promotion, 30(4), 231–241. 10.1177/0890117116639572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier K, Monson CM, Wonderlich SA, MacDonald DE, & Olmsted MP (2017). Frontline clinicians’ perspectives on and utilization of trauma-focused therapy with individuals with eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 25(1), 22–36. 10.1080/10640266.2016.1207456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gerko K, Hughes ML, Hamill M, & Waller G (2005). Reported childhood sexual abuse and eating-disordered cognitions and behaviors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 29(4), 375–382. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderweele TJ, & Vansteelandt S (2010). Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(12), 1339–1348. 10.1093/aje/kwq332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veras JL-DA, Ximenes RCC, De Vasconcelos FMN, & Sougey EB (2017). Risk of suicide in adolescents with symptoms of eating disorders and depression. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 6(3). 10.4172/2167-1044.1000274 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von Eye A, & Bergman LR (2003). Research strategies in developmental psychopathology: Dimensional identity and the person-oriented approach. Development and Psychopathology, 15(3), 553–580. 10.1017/S0954579403000294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmingham JM, Handley ED, Rogosch FA, Manly JT, & Cicchetti D (2019). Identifying maltreatment subgroups with patterns of maltreatment subtype and chronicity: A latent class analysis approach. Child Abuse & Neglect, 87, 28–39. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, & Harris TR (1996). Childhood sexual abuse and bulimic behavior in a nationally representative sample. American Journal of Public Health, 86(8), 1082–1086. 10.2105/AJPH.86.8_Pt_1.1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]