Abstract

Genome sequencing projects revealed massive cryptic gene clusters encoding the undiscovered secondary metabolites in Streptomyces. To investigate the metabolic products of silent gene clusters in Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10 (CGMCC 2644), we used site-directed mutagenesis to generate ten mutants with point mutations in the highly conserved region of rpsL (encoding the ribosomal protein S12) or rpoB (encoding the RNA polymerase β-subunit). Among them, L10/RpoB (H437Y) accumulated a dark pigment on a yeast extract-malt extract-glucose (YMG) plate. This was absent in the wild type. After further investigation, a novel angucycline antibiotic named anthrachamycin was isolated and determined using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic techniques. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) were performed to investigate the mechanism underlying the activation effect on the anthrachamycin biosynthetic gene cluster. This work indicated that the rpoB-specific missense H437Y mutation had activated anthrachamycin biosynthesis in S. chattanoogensis L10. This may be helpful in the investigation of the pleiotropic regulation system in Streptomyces.

Keywords: Streptomyces, Cryptic gene cluster, Site-directed mutagenesis, Secondary metabolism

1. Introduction

Natural products, also regarded as secondary metabolites, are valuable and reliable sources for medical development. They are widely used in veterinary medicine, human therapies, agriculture, and other areas (Bérdy, 2005; Chen et al., 2016). It has been reported that over 50% of antibiotics have been produced by Actinomycetes (Demain, 2014). Genome sequencing projects revealed that Streptomyces regularly contains more than 20 putative gene clusters for the biosynthesis of peptides, polyketides, bacteriocins, terpenoids, and other natural products (Staunton and Weissman, 2001; Hopwood, 2006; Moore, 2008; Nett et al., 2009). However, many of these gene clusters are silent, hindering the discovery of new natural products (Chen et al., 2016). In Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10 (CGMCC 2644), only a small number of these products have been isolated, as directed by three metabolic pathways. However, more than 30 putative secondary metabolic gene clusters remain silent (Guo et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015).

Because of urgent clinical need, many approaches have been established to expand chemical diversities and clinical application of bioactive molecules in Streptomyces. Compared to metabolic engineering or classical random approaches for antibiotic production, ribosome engineering represents both a practicable and economical approach to the enhancement of antibiotic production and to the activation of silent gene clusters (Wang et al., 2008). It uses ribosome-targeting drugs to select strains with mutations in RNA polymerase, ribosome proteins, and translation factors (Fu et al., 2014; Ochi, 2017).

A silent gene cluster was activated when a specific rpoB mutation was introduced into S. chattanoogensis L10. A novel angucycline-like antibiotic with a moderate antioxidant capacity was isolated. Angucyclines are important antibiotics produced by Streptomyces sp., and they achieve structural diversity in glycosylation, amino acid incorporation, ring cleavage and epoxidation (Ma et al., 2015; Bao et al., 2018). Angucyclines have been applied as antitumor agents, antioxidants, and in other bioactive fields (Kharel et al., 2012).

The mechanism underlying this distinct activation by the rpoB mutation has also been studied using electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. The results indicated that both the upregulated expression of genes (involved in pleiotropic regulation on antibiotic production) at the transcriptional levels and the AdpAch (AdpA of S. chattanoogensis origin) regulatory effect on the cha gene cluster might be responsible for the activation of anthrachamycin biosynthesis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains and media

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. S. chattanoogensis L10 and its derivatives were grown at 28 °C on yeast extract-malt extract-glucose (YMG) solid medium. Trypticase soy broth was used for extracting genomic DNA (Du et al., 2011). Escherichia coli DH5α and E. coli BL21 (DE3) were used as cloning and expression hosts, respectively. E. coli cells were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) medium with the appropriate concentration of antibiotics for propagating plasmids.

2.2. Construction of the plasmids and mutant strains

All plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 and Table S2, respectively. The site-directed mutagenesis plasmids were constructed following the method of Okamoto-Hosoya et al. (2003), with slight modifications. rpsL and rpoB were amplified with primer pairs F1/R1 and F2/R2, respectively. The resulting DNA fragments were sequenced and cloned into the EcoRI/EcoRV site of pKC1139 (Muth et al., 1989), generating the recombinant plasmids pKC1139-rpsL and pKC1139-rpoB, respectively. These plasmids were used as templates for the following experiments as illustrated in Fig. S1. After the second round of PCR and digestion with EcoRI and HindIII, the fragments were ligated into pKC1139. The obtained plasmids were sequenced, harboring the desired mutation in rpsL or rpoB, to yield the replicating plasmids pKCmu1 to pKCmu10. The pKC1139-based mutational cloning plasmids were introduced into S. chattanoogensis L10 by conjugation according to standard procedures (Mao et al., 2015). The mutant strains were selected after double crossover. The coding regions of rpsL or rpoB in the mutant strains were determined by DNA sequencing analysis, confirming that the wild-type gene was substituted with the mutant allele via homologous recombination.

chaA was knocked out by an in-frame deletion in ZJUY1. Two 1-kb DNA fragments flanking the chaA coding region were amplified with primer pairs F13/R13 and F14/R14, respectively. The resulting DNA fragments were digested with HindIII/XbaI and XbaI/EcoRV, respectively, and then sequenced and ligated into pKC1139, generating pKC1139-ΔchaA. The plasmid was then introduced into ZJUY1 via E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (Mao et al., 2015). The double crossover mutants were screened for apramycin-sensitivity and confirmed by PCR. The chaA mutant was named ZJUY11.

chaI was knocked out using an in-frame deletion in ZJUY1. Two 1-kb DNA fragments flanking the chaI coding region were amplified with the primer pairs F27/R27 and F28/R28, respectively. The resulting DNA fragments were digested with XbaI/HindIII and XbaI/EcoRI, respectively, sequenced and ligated into pKC1139, generating pKC1139-ΔchaI. The plasmid was then introduced into ZJUY1 by conjugation according to standard procedures (Mao et al., 2015). The double crossover mutants were screened for apramycin-sensitivity and confirmed by PCR. The chaI mutant was named ZJUY12.

The coding region of adpAch was amplified with primer pair F15/R15 and sequentially cloned into the EcoRI/HindIII site of pET32a to generate the expression plasmid pET32a-adpAch. The promoter region of chaI was amplified with the primer pair F17/R17 and cloned into a pClone 007 Blunt Simple Vector (Tsingke, Hangzhou, China) to obtain pClone1 for the promoter-probing assay. All the PCR reactions were conducted with KOD Plus-Neo (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan).

2.3. HPLC analysis of anthrachamycin

A 0.5-mL aliquot of the culture was extracted with 0.5 mL of ethyl acetate three times. To compare the metabolic profiles, the crude extracts of different strains were separately filtered and injected into an Agilent 1260 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent, Beijing, China) fitted with an Eclipse Plus XDB-C18 column (5 μm, ø4.6 mm×150 mm) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and ultraviolet (UV) detection at 316 nm. We used chromatography with a linear gradient from 5% to 44% (v/v) acetonitrile over 35 min, with a subsequent isocratic stage of 100% acetonitrile for 5 min. The column was further equilibrated with 5% (v/v) acetonitrile for 5 min.

2.4. Fermentation and isolation of anthrachamycin

S. chattanoogensis L10 and its derivative strains were cultured on YMG solid medium. After incubation for 7 d at 28 °C, spores collected from YMG plates were inoculated into a rotary shaker with 35 mL TNG (15 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L NaCl, 17.5 g/L glucose) medium (Liu et al., 2015) and incubated at 220 r/min and 30 °C for 18 h. The obtained seed culture was added to 35 mL yeast extract-malt extract (YEME) medium to give an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.15. This was fermented at 30 °C in one 250-cm3 flask for 5 d. The culture was harvested at different time points for RNA preparation or metabolic analysis.

For large-scale fermentation, the obtained seed culture was incubated in two 1000-cm3 flasks (each with 4 mL of pre-culture) containing liquid TNG medium (200 mL). The second seed culture was incubated at 220 r/min and 30 °C for 24 h and then transferred into a 15-L stirred tank fermenter with 7.5 L YEME medium. Fermentation was carried out at 250 r/min and 30 °C for 5 d with an air-flow rate of 1 m3/(m3·min).

The fermentation broth was centrifuged at 3500g for 40 min. The resulting mycelial sediment was washed three times with methanol, and the supernatant was extracted with ethyl acetate three times. Both extracts were mixed and evaporated to dryness under vacuum at 40 °C, which afforded 12.3 g of dark solid. The solid was purified by CombiFlash® chromatography with an 8:1 ethyl acetate/methanol mixture as an eluent. The product was purified using a Lumtech semi-preparative HPLC apparatus (column: Agilent XDB-C18, 5 μm, ø9.4 mm×250 mm; eluent: solvent A 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water, solvent B 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile; isocratic gradient: 28% (v/v) acetonitrile; flow rate: 3 mL/min) to yield anthrachamycin. After concentration in vacuo to dryness at 20 °C, a yield of 15.0 mg anthrachamycin was obtained.

2.5. Structure elucidation

High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESI-MS) was recorded using an AB Sciex 5600 QTOF system (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were gained using a Bruker Advance 600 spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Milton, Canada). Anthrachamycin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO-d6) for NMR experiments. The optical rotations were obtained on a PerkinElmer-341 polarimeter (PerkinElmer, Boston, USA). Anthrachamycin: C31H32O15; amorphous red solid; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) and 13C NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) (Table S3); infrared spectroscopy (IR; KBr) ṽmax=3384, 2910, 1624, 1458, 1386, 1078 cm−1; UV/Vis (methanol) λmax=235, 264, 316, 428 nm; (+)-ESI-MS m/z 667.25 [M+Na]+, (−)-ESI-MS m/z 643.05 [M-H]−; (+)-HRESI-MS m/z 667.1641 [M+Na]+, calculated 667.1633.

2.6. ABTS assay

The radical scavenging activity of anthrachamycin was evaluated by the 2,2'-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) radical cation (ABTS•+) assay following the methods of Erel (2004). A total of 200 μL of reagent 1 (0.4 mol/L acetate buffer, pH 5.8), 5 μL of sample (different concentrations of anthrachamycin and ascorbic acid both dissolved in DMSO), and 20 μL of reagent 2 (the ABTS in 30 mmol/L acetate buffer, pH 3.6) were mixed. After 5 min, the decrease in absorbance at 660 nm was monitored. The ABTS•+ radical scavenging activity of anthrachamycin is expressed as mg vitamin C equivalent (VCE)/g lyophilized powder (LP). All reactions were performed in triplicate.

2.7. FRAP assay

The measurement of the ferric reducing capacity of anthrachamycin follows the method of Floegel et al. (2011) and Bao et al. (2016) with modifications. A total of 20 μL of anthrachamycin was mixed with 700 μL of ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) solution. The mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 593 nm. The FRAP values of different concentrations of anthrachamycin were expressed as the known concentrations of mixtures with ferrous ions. All reactions were performed in triplicate.

2.8. RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

RNA samples of S. chattanoogensis strains were isolated from YEME liquid culture. RNA was prepared following the method of Liu et al. (2015) and Wang et al. (2017). Genomic DNA contamination was diminished by RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan). The DNA contamination was confirmed by PCR. RNA was transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) with Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV; RNase H−, TaKaRa). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa). The primer pairs F18/R18, F19/R19, F20/R20, F21/R21, F22/R22, F23/R23, F24/R24, F25/R25, and F26/R26 were used to detect the transcriptional levels of relA, relC, chaA, chaGT1, chaM, chaS, chaI, adpA, and hrdB, respectively. The transcription of hrdB was used as an internal reference. The fold changes of relA, relC, chaA, chaGT1, chaM, chaS, chaI, and adpA expression were quantified as 2−ΔΔCT according to the instruction (TaKaRa). All reactions were performed in triplicate.

2.9. Expression and purification of AdpAch

E. coli BL21 (DE3) carrying pET32a-adpAch was cultured in LB medium at 37 °C to OD600=0.6 and induced with 0.01 mmol/L isopropyl thiogalactoside (IPTG) for further 18 h at 16 °C. Cells were collected and disrupted by ultrasonication in buffer A (pH 8.0, 50 mmol/L Tris, 500 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L imidazole). The supernatant was then obtained by centrifugation (13 000g for 50 min). Soluble His6-TrxA-AdpAch (AdpAch) was purified with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) His Bind resin (Novagen, Wisconsin, USA) chromatography following the manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in buffer B (buffer A plus 250 mmol/L imidazole).

2.10. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The 5' end with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled probes were amplified with primer pair F16/R16 from the corresponding plasmids. These probes were gel-purified and eluted in sterile water. About 400 ng of probes were incubated with proteins at 30 °C for 30 min in buffer (100 mmol/L Na2HPO4 (pH 8.0), 20 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.5), 50 μg/mL sheared sperm DNA, and 5% (v/v) glycerol). Reactions were performed on 5% (0.05 g/mL) acrylamide gels in a 0.5×Tris-borate/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TBE) running buffer and run at 100 V for 1.5 h on ice.

3. Results

3.1. Introduction of mutations into rpsL or rpoB

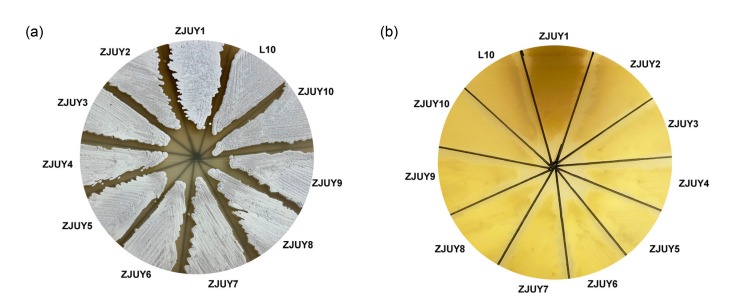

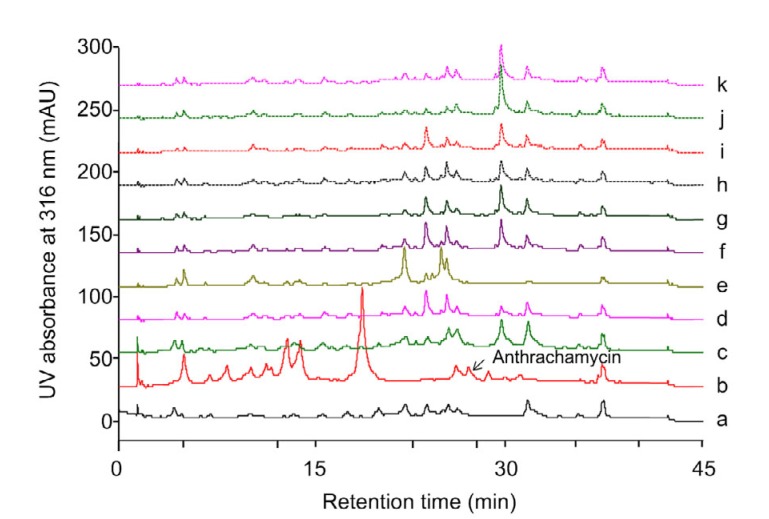

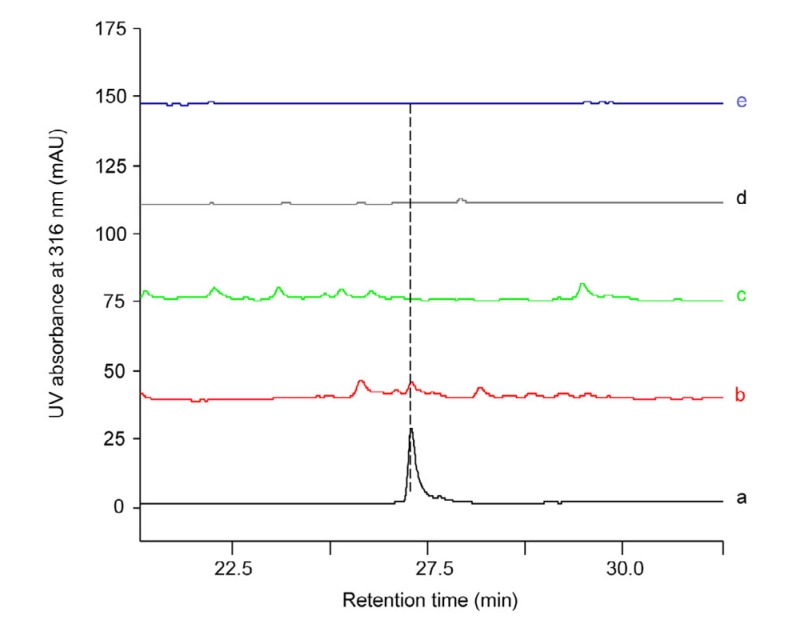

Some specific mutations in rpsL or rpoB may exhibit positive effects on cryptic gene clusters in Streptomyces (Hu et al., 2002; Okamoto-Hosoya et al., 2003; Ochi, 2017). To activate silent gene clusters in S. chattanoogensis L10, we constructed mutant strains ZJUY1 to ZJUY10 by introducing specific point mutations into rpsL or rpoB. Compared to the wild-type strain and other mutants, ZJUY1 accumulated a dark pigment on YMG solid medium (Fig. 1). The HPLC profiles of different strains also indicated that new metabolites were formed in ZJUY1 (Fig. 2). To investigate novel metabolites in ZJUY1 and avoid repetitive research on the compound as in previous studies (Guo et al., 2015), some peaks with novel UV absorptions were prioritized for further investigation.

Fig. 1.

Morphological development of L10 and ZJUY1–ZJUY10

Spores of all strains were patched on the yeast extract-malt extract-glucose (YMG) medium for 7 d. (a) The above side of plate; (b) The reverse side of plate

Fig. 2.

HPLC analysis of the crude extracts of L10 and ZJUY1–ZJUY10

Crude extracts of L10 (a), ZJUY1 (b), ZJUY2 (c), ZJUY3 (d), ZJUY4 (e), ZJUY5 (f), ZJUY6 (g), ZJUY7 (h), ZJUY8 (i), ZJUY9 (j), ZJUY10 (k). The detection wavelength was 316 nm

3.2. Elucidation of anthrachamycin

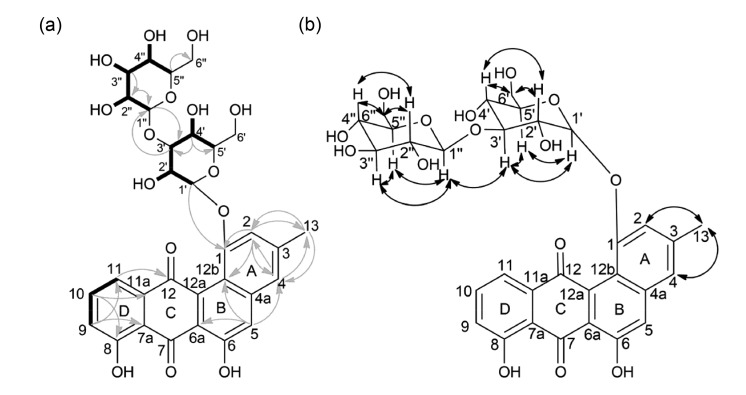

Anthrachamycin was isolated as an amorphous red solid, which displayed a negative specific rotation (−1.60, (c 0.25, DMSO)). HRESI-MS revealed the molecular formula as C31H32O15 (m/z 667.1641 [M+Na]+, calculated 667.1633) with sixteen unsaturation degrees. The IR spectrum of anthrachamycin showed an absorption band at 3384 cm−1 (hydroxyl group). The one-dimensional (1D) and 2D NMR spectra (Table S3 and Fig. S2–Fig. S9) revealed 6 sp2-hybridized methines, 10 sp3-hybridized methines, 2 sp3-hybridized methylenes, 1 sp3-hybridized methyl, and 12 quaternary carbons. The 1H NMR of anthrachamycin revealed two phenolic hydroxyl protons (δH=11.56) and six aromatic protons (δH=7.80, 7.50, 7.46, 7.31, 7.29, 7.01). The heavy mental binding capacity (HMBC) signals C-2/13-H3, C-4/13-H3, C-13/2-H, and C-13/4-H revealed a methyl group attached to C-3 (Fig. 3a). Ring A and ring B were connected by the quaternary carbons δC=139.7 (C-4a) and δC=115.8 (C-12b) with HMBC signals C-4a/H-4, C-12b/H-2, and C-12b/H-5. Ring C showed connectivity with ring B through the HMBC signal C-6a/H-5. The typical carbonyl chemical shifts (δ=191.5 and δ=185.3) indicated the structure of ring C as quinone. The connection between ring C and ring D was highlighted by the HMBC signals C-7a/H-9, C-11a/H-10, and C-12/H-11. Ring D showed a phenolic hydroxyl group and correlated spectroscopy (COSY) signals 9-H/10-H and 10-H/11-H. The HMBC signals in ring D supported the phenolic group at C-8. The gross structure of the aglycone of anthrachamycin was determined by analysis of the NMR data and by comparison with the NMR data of dehydrorabelomycin (Lombó et al., 2009) and amycomycin B (Guo et al., 2012). The 1H NMR of anthrachamycin revealed two distinct signals for anomeric protons at δH=4.92 and δH=4.35 and the 1H-1H coupling constants J (1'-H, 2'-H)=5.9 and J (1''-H, 2''-H)=7.8, which indicated the presence of two β-sugars. Comparison of our findings with the literature (Francis et al., 1998; El-Toumy et al., 2012) indicated the two sugars as glucopyranoses. The HMBC signals C-1/H-1', C-3'/H-1'' and nuclear overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) signal 3'-H/1''-H (Fig. 3b) indicated that a glycosyl moiety was attached to C-1 and that the link is glucose (1→3).

Fig. 3.

2D NMR analysis of anthrachamycin

(a) Selected HMBC (→) and COSY (bond) correlations of anthrachamycin. (b) Selected NOESY correlations of anthrachamycin. NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; HMBC: heavy mental binding capacity; COSY: correlated spectroscopy; NOESY: nuclear overhauser enhancement spectroscopy

Based on the above evidence, anthrachamycin was identified as dehydrorabelomycin-1-O-β-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)-β-glucopyranoside. The structure of anthrachamycin resembles those of amycomycin B (dehydrorabelomycin-11-O-α-rhamnopyranoside) and actinosporin C (dehydrorabelomycin-1-O-α-rhamnopyranose-8-O-α-rhamnopyranoside) (Grkovic et al., 2014), while the glycosylation position and the substituents of sugar moieties of these angucyclines are different. To the best of our knowledge, this work represents the first isolation of anthrachamycin from nature.

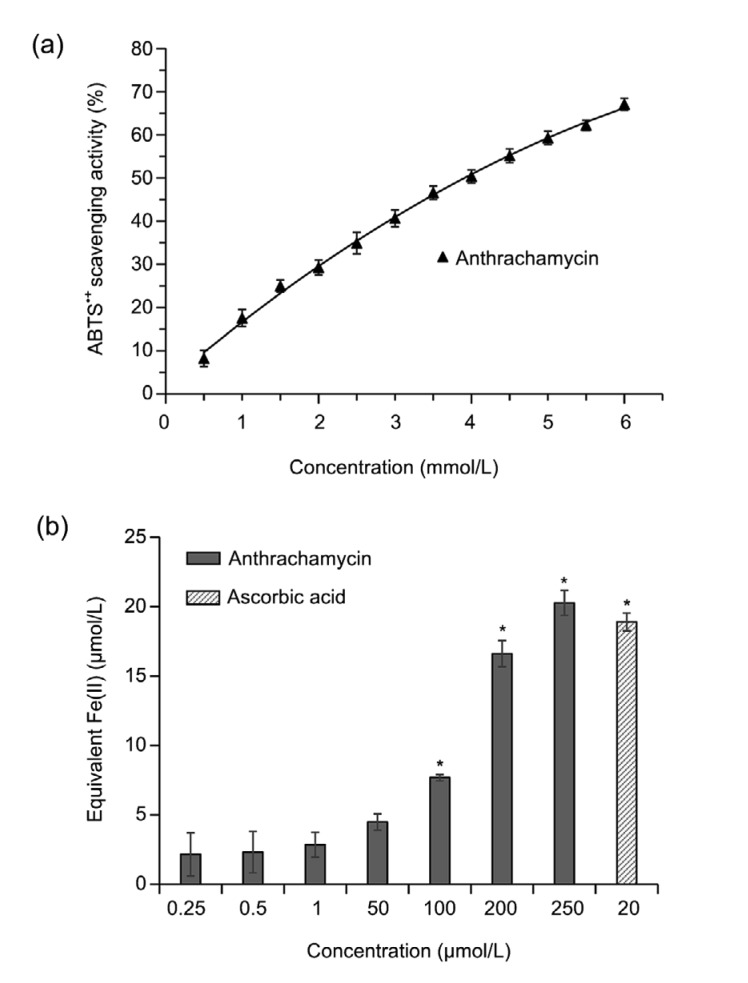

3.3. Antioxidant activity of anthrachamycin

Anthrachamycin exhibited no inhibitory effect against human HepG2 hepatoma or human MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines (data not shown) and no antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, E. coli K12, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 67736, or Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 (data not shown). The antioxidant activity of anthrachamycin was evaluated by ABTS and FRAP assays. In the ABTS assay, the antioxidant activity of anthrachamycin was 67.28 mg VCE/g LP. In the FRAP assay, the antioxidant activity of anthrachamycin was 24.31 mg VCE/g LP. Moreover, anthrachamycin showed a concentration-dependent response in both ABTS (Fig. 4a) and FRAP (Fig. 4b) antioxidant assays. These results indicate that anthrachamycin has a moderate antioxidant capacity, which is similar to the result that the analogue actinosporin C exhibits potent antioxidant activity in the FRAP assay (Grkovic et al., 2014).

Fig. 4.

Antioxidant activity assay of anthrachamycin

(a) Antioxidant capacity of anthrachamycin was measured using 2,2'-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonate) (ABTS) assay. The results are expressed as arithmetic mean±standard deviation (n=3). (b) The ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of cell-free solutions of anthrachamycin was assessed using photometric quantification (* P<0.05, significantly different from control (DMSO)). The results are expressed as arithmetic mean±standard deviation (n=3). Ascorbic acid was used as an antioxidant standard

3.4. A cryptic gene cluster activated in a rpoB mutant strain

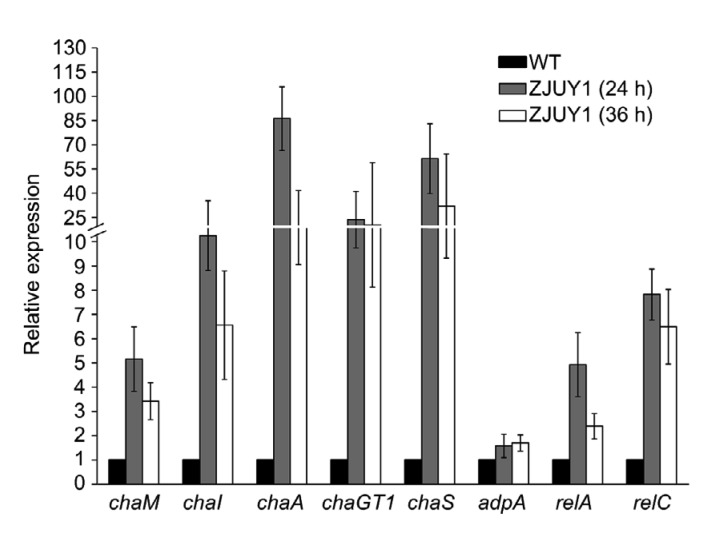

Angucyclines are type II polyketide synthetase (PKS)-engineered natural products (Kharel et al., 2012). Based on the genomic analysis of S. chattanoogensis L10, a landomycin analog PKS gene cluster named cha (Zhou et al., 2015) was assumed to be responsible for the biosynthesis of anthrachamycin. To validate this gene cluster, we constructed a strain of ZJUY11 (ΔchaA/RpoB (H437Y)) by deleting the corresponding PKS α-subunit gene chaA in ZJUY1. HPLC analysis indicated the abolishment of anthrachamycin production in ZJUY11 (Fig. 5). The transcriptional levels of selected genes in cha gene cluster were examined in ZJUY1 and the wild-type strain by qRT-PCR analysis (chaM representing the post-PKS genes; chaI as a pathway-specific regulator; chaA on behalf of the minimal PKS genes; chaGT1 standing for the glycosyltransferase genes; chaS representing the deoxy-hexose genes). At 24 h, the transcript levels of chaM, chaI, chaA, chaGT1, and chaS from ZJUY1 were about 5.2, 13.8, 86.2, 23.7, and 62.3 times that of the wild-type strain, respectively (Fig. 6). At 36 h, the transcript levels of chaM, chaI, chaA, chaGT1, and chaS in ZJUY1 were about 3.4, 6.6, 18.8, 20.4, and 32.1 times that of the wild-type strain, respectively. These results indicated that these genes within the cha gene cluster were highly expressed at the transcriptional levels in ZJUY1 at 24 and 36 h.

Fig. 5.

HPLC analysis of the crude extracts of ZJUY1, L10, ZJUY11, and ZJUY12

(a) Authentic samples of anthrachamycin. (b–e) Crude extracts of ZJUY1 (b), L10 (c), ZJUY11 (d), and ZJUY12 (e). The detection wavelength was 316 nm

Fig. 6.

Transcriptional analysis of chaM, chaI, chaA, chaGT1, chaS, adpA, relA, and relC by qRT-PCR

All RNA samples were isolated from 24 or 36 h in yeast extract-malt extract (YEME) medium. hrdB transcription was monitored and used as internal control. Relative expression was shown as expression ratio (arithmetic mean) of chaM, chaI, chaA, chaGT1, chaS, adpA, relA, or relC to hrdB as measured in three independent experiments. All the standard deviations (SDs) are shown as error bars. WT: wild type

In Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), specific rif mutations can activate the biosynthesis of actinorhodin, indicating that the rif mutation pleiotropically regulates antibiotic biosynthesis (Hu et al., 2002). To investigate the mechanism activating anthrachamycin biosynthesis, we detected the transcript levels of three widely presented genes which may be involved in pleiotropic regulation on secondary metabolism: relA (ppGpp (guanosine 5'-diphosphate 3'-diphosphate) synthetase gene), relC (encoding ribosomal protein L11), and adpA (encoding a pleiotropic regulator AdpA) in ZJUY1 and in the wild-type strain. The transcriptional levels of relA and relC were both increased more than two times at 24 and 36 h in ZJUY1 (Fig. 6) compared to that of the wild-type strain. Moreover, the transcriptional level of adpA was marginally increased during the early stage for secondary metabolism in ZJUY1. Interestingly, the production of landomycin A (a glycosylated angucycline) was enhanced when several heterologous adpA genes were overexpressed in Streptomyces cyanogenus S136 (Yushchuk et al., 2018). Yushchuk et al. (2018) also believed that the positive effect of adpA overexpression on landomycin biosynthesis is mediated by the lanI. Given that anthrachamycin is biosynthesized by enzymes encoded in the cha gene cluster and the transcriptional levels of adpA and chaI were increased at 24 and 36 h for secondary metabolism in ZJUY1, we speculate that AdpAch may be also involved in the regulation of chaI.

3.5. chaI, encoding a putative regulator in cha gene cluster

An in silico analysis of the cha gene cluster revealed that chaI encodes a Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory protein (SARP) (Rebets et al., 2005, 2008). The deduced amino acid sequence of ChaI resembles other angucycline biosynthesis positive regulators, such as LanI (52% identity to ChaI) in S. cyanogenus S136 (Rebets et al., 2003), JadR1 (57% identity to ChaI) in Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230 (Yang et al., 2001), and LndI (56% identity to ChaI) in Streptomyces globisporus 1912 (Rebets et al., 2003). As for LanI and JadR1, ChaI can also be classified as a regulator protein of the OmpR-PhoB subfamily (Fu et al., 2014), with α-helices and β-folds in their C-terminal regions and specific winged helix structures, responsible for DNA binding and productive interaction with RNA polymerase (Makino et al., 1996; Martínez-Hackert and Stock, 1997; Rebets et al., 2003). To investigate the function of ChaI, we deleted the chaI gene in ZJUY1 to obtain ZJUY12 (ΔchaI/RpoB (H437Y)). HPLC analysis indicated the abolishment of the anthrachamycin product in ZJUY12 (Fig. 5), which suggested that chaI may play an essential role in the biosynthesis of anthrachamycin.

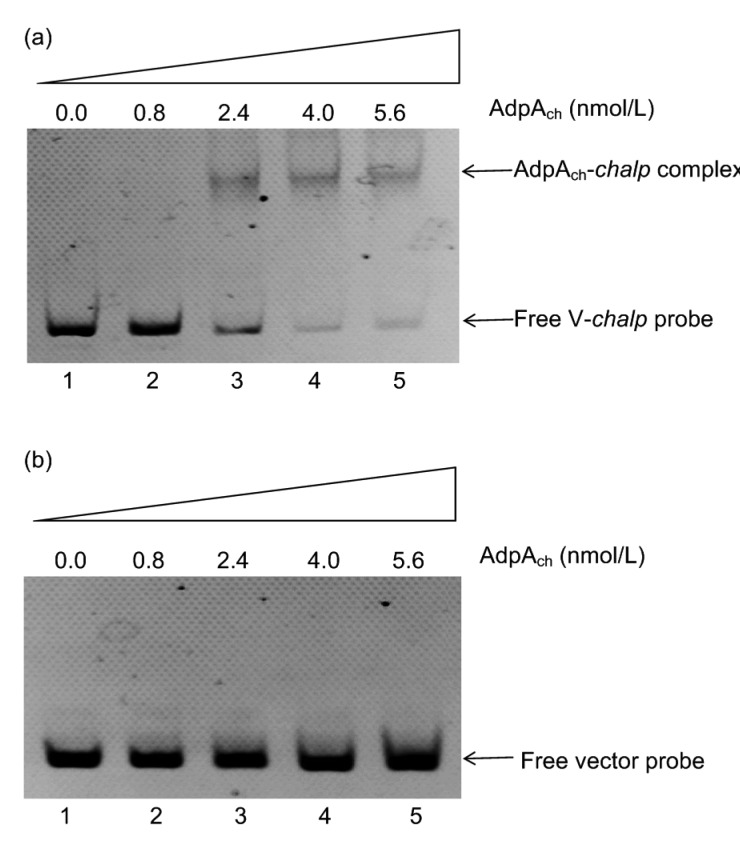

3.6. AdpAch binding to upstream of anthrachamycin biosynthetic gene chaI

In S. cyanogenus S136, the AdpA-mediated boost effect on landomycin A production is dependent on the lanI gene (Yushchuk et al., 2018). To test whether AdpAch directly regulates chaI, EMSA was performed. Based on previous studies on AdpAch in S. chattanoogensis L10 (Yu et al., 2014), we screened the nucleotide sequence of the promoter region of chaI with the consensus sequence 5'-TGGCSNGW WY-3' (where W is A or T, S is G or C, Y is T or C, and N is any nucleotide) using a multiple expectation maximization for motif elicitation (MEME) search. When setting the P-value to a threshold of less than 0.0001, one potential AdpA binding site could be suggested as TGGCGTGAAC. EMSA data showed that His6-TrxA-AdpAch could bind to the promoter region of chaI and form complex bands (Fig. 7a), while no shift bands were observed in the control reaction (Fig. 7b). This confirmed the binding specificity of AdpAch to the chaI promoter (chaIp) and suggested that AdpAch regulates the transcription of chaI by specifically binding to the promoter region of chaI.

Fig. 7.

AdpAch binding to the chaI promoter (chaIp)

The 5-FAM-labeled chaIp (V-chaIp) was used as a probe and the 5-FAM-labeled void vector was a negative control. (a) Lanes 1 to 5, about 4 pmol/L (400 ng) 5-FAM-labeled chaIp (V-chaIp) probes from pClone1 with 0, 0.8, 2.4, 4.0, or 5.6 nmol/L of purified His6-Trx-AdpAch, respectively. (b) Lanes 1 to 5, about 4 pmol/L (400 ng) 5-FAM-labeled void vector from pClone007 Blunt Simple Vector with 0, 0.8, 2.4, 4.0, or 5.6 nmol/L of purified His6-Trx-AdpAch, respectively. FAM: 6-carboxyfluorescein

4. Discussion

Ribosome engineering mainly introduces mutations conferring drug resistance and selects various mutant forms based on colony size, morphology, or pigment formation (Ochi, 2017). Differing from the spontaneous generation of drug-resistant mutations, we used site-directed mutagenesis to directly construct target mutant strains and avoid the isolation of multiple colonies. However, the efficiency of this approach is unpredictable as mutant sites may exhibit different effects on bacterial fitness and the activation of various silent gene clusters (Craney et al., 2013; Tanaka et al., 2013). It has now become feasible to integrate ribosome engineering with other genome mining strategies to improve activation efficiency and activate biosynthetic gene clusters of interest.

The mechanism activating silent genes by rpoB mutations in Streptomyces is not entirely clear but involves the upregulation expression of cryptic genes at the transcriptional levels (Gomez-Escribano and Bibb, 2011; Ochi, 2017).

AdpA, a transcriptional factor of the AraC/XylS-type regulatory protein family, is widely present in Streptomyces genomes and frequently influences the transcription of antibiotic biosynthesis genes both directly and indirectly (Yu et al., 2014; Yushchuk et al., 2018). It has been reported that AdpA positively regulated secondary metabolites biosynthesis by controlling cluster-situated regulators in Streptomyces griseus (Ohnishi et al., 1999), Streptomyces roseosporus (Mao et al., 2015), Streptomyces avermitilis (Komatsu et al., 2010), Streptomyces clavuligerus (López-Garcia et al., 2010), and S. chattanoogensis (Du et al., 2011). In S. griseus, the transcriptional level of adpA was found to be impaired in the early and late growth phases when the Q424K mutation was introduced into RpoB. Conversely, the rsmG mutation (conferring a low-level resistance to streptomycin) enhanced the expression of adpA (Tanaka et al., 2013). Similarly, the transcript level of adpA was marginally increased in ZJUY1. EMSA results suggest that AdpAch regulates the transcription of chaI by specifically binding to the promoter region of chaI. This is consistent with the case that AdpA is involved in landomycin A biosynthetic regulatory network (Yushchuk et al., 2018). Taken together with the results mentioned above, it is possible that the transcriptional level changes in adpA and AdpAch’s regulatory effect on chaI may influence cha cluster expression in ZJUY1.

RelA and RelC are necessary for the biosynthesis of ppGpp, which may participate significantly in the activation of cryptic gene clusters (Hesketh et al., 2001; Inaoka et al., 2004; Ochi, 2017). In S. coelicolor A(3)2 and S. lividans, alteration at His-437 to Tyr or Arg in RpoB circumvented the detrimental effects of antibiotic production resulting from the lack of ppGpp due to relA or relC mutations (Inaoka et al., 2004). In ZJUY1, the transcriptional levels of relA and relC were also remarkably enhanced. Further work is required to determine the molecular basis for the transcriptional level changes of relA and relC in RpoB mutant strains.

The results presented in this study revealed that the activation effect on anthrachamycin biosynthesis by the rpoB mutation is attributed, at least in part, to the transcriptional changes of the genes corresponding to stringent response and pleiotropic regulation (Fig. S10). Transcriptome and proteome analysis will be performed to further investigate the changes in gene expression and protein biosynthesis in ZJUY1. It is possible that some novel secondary metabolites were activated with low yields in ZJUY2–ZJUY10 and further studies are required to enhance the activation efficiency and detect the novel metabolites of silent gene clusters.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a silent gene cluster was activated when we used site-directed mutagenesis to generate an RpoB mutation in S. chattanoogensis L10. After further investigation into the metabolites of L10/RpoB (H437Y), a novel angucycline-like antibiotic named anthrachamycin was isolated. qRT-PCR and EMSA were performed to further investigate the mechanism underlying the activation effect on the anthrachamycin biosynthetic gene cluster. The work presented here will be helpful towards further investigation of the pleiotropic regulation system in Streptomyces.

List of electronic supplementary materials

Strains and plasmids used in this study

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

1H and 13C NMR data of anthrachamycin in DMSO-d6(600 MHz)

Schematic representation of overlapping PCR strategy for introducing mutations into rpsL or rpoB

UV absorption of anthrachamycin

1H NMR spectrum of anthrachamycin

13C NMR spectrum of anthrachamycin

Distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer(DEPT135) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Correlated spectroscopy (COSY) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Nuclear overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Heavy mental binding capacity (HMBC) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Speculated mechanism for activating anthrachamycin biosynthesis

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31520103901 and 3173002)

Contributors: Zi-yue LI, Qing-ting BU, Jue WANG, and Yu LIU performed the experiments. Zi-yue LI and Qing-ting BU wrote the manuscript. Xin-ai CHEN, Xu-ming MAO, and Yong-Quan LI revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Therefore, all authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and security of the data.

Electronic supplementary materials: The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1900344) contains supplementary materials, which are available to authorized users

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Zi-yue LI, Qing-ting BU, Jue WANG, Yu LIU, Xin-ai CHEN, Xu-ming MAO, and Yong-Quan LI declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Bao J, He F, Li YM, et al. Cytotoxic antibiotic angucyclines and actinomycins from the Streptomyces sp. XZHG99T. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2018;71(12):1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/s41429-018-0096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao T, Wang Y, Li YT, et al. Antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of tartary buckwheat rice flavonoids after in vitro digestion. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol) 2016;17(12):941–951. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bérdy J. Bioactive microbial metabolites. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2005;58(1):1–26. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JW, Wu QH, Hawas UW, et al. Genetic regulation and manipulation for natural product discovery. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100(7):2953–2965. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craney A, Ahmed S, Nodwell J. Towards a new science of secondary metabolism. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2013;66(7):387–400. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demain AL. Importance of microbial natural products and the need to revitalize their discovery. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;41(12):185–201. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1325-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du YL, Shen XL, Yu P, et al. Gamma-butyrolactone regulatory system of Streptomyces chattanoogensis links nutrient utilization, metabolism, and development. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(23):8415–8426. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05898-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Toumy SA, El Souda SS, Mohamed TK, et al. Anthraquinone glycosides from Cassia roxburghii and evaluation of its free radical scavenging activity. Carbohydr Res. 2012;360:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erel O. A novel automated direct measurement method for total antioxidant capacity using a new generation, more stable ABTS radical cation. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(4):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Floegel A, Kim DO, Chung SJ, et al. Comparison of ABTS/DPPH assays to measure antioxidant capacity in popular antioxidant-rich US foods. J Food Compos Anal. 2011;24(7):1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2011.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis GW, Aksnes DW, Holt Ø. Assignment of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of anthraquinone glycosides from Rhamnus frangula. Magn Reson Chem. 1998;36(10):769–772. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-458X(1998100)36:10<769::AID-OMR361>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu P, Jamison M, La S, et al. Inducamides A-C, chlorinated alkaloids from an RNA polymerase mutant strain of Streptomyces sp. Org Lett. 2014;16(21):5656–5659. doi: 10.1021/ol502731p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Escribano JP, Bibb MJ. Engineering Streptomyces coelicolor for heterologous expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4(2):207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grkovic T, Abdelmohsen UR, Othman EM, et al. Two new antioxidant actinosporin analogues from the calcium alginate beads culture of sponge-associated Actinokineospora sp. strain EG49. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24(21):5089–5092. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo YY, Li H, Zhou ZX, et al. Identification and biosynthetic characterization of natural aromatic azoxy products from Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10. Org Lett. 2015;17(24):6114–6117. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo ZK, Liu SB, Jiao RH, et al. Angucyclines from an insect-derived actinobacterium Amycolatopsis sp. HCa1 and their cytotoxic activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22(24):7490–7493. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesketh A, Sun J, Bibb M. Induction of ppGpp synthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) grown under conditions of nutritional sufficiency elicits actII-ORF4 transcription and actinorhodin biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39(1):136–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopwood DA. Soil to genomics: the Streptomyces chromosome. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu HF, Zhang Q, Ochi K. Activation of antibiotic biosynthesis by specified mutations in the rpoB gene (encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit) of Streptomyces lividans. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(14):3984–3991. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.14.3984-3991.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inaoka T, Takahashi K, Yada H, et al. RNA polymerase mutation activates the production of a dormant antibiotic 3,3'-neotrehalosadiamine via an autoinduction mechanism in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(5):3885–3892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kharel MK, Pahari P, Shepherd MD, et al. Angucyclines: biosynthesis, mode-of-action, new natural products, and synthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29(2):264–325. doi: 10.1039/c1np00068c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu M, Uchiyama T, Omura S, et al. Genome-minimized Streptomyces host for the heterologous expression of secondary metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(6):2646–2651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914833107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu SP, Yu P, Yuan PH, et al. Sigma factor WhiGch positively regulates natamycin production in Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(6):2715–2726. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lombó F, Abdelfattah MS, Braña AF, et al. Elucidation of oxygenation steps during oviedomycin biosynthesis and generation of derivatives with increased antitumor activity. ChemBioChem. 2009;10(2):296–303. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López-Garcia MT, Santamarta I, Liras P. Morphological differentiation and clavulanic acid formation are affected in a Streptomyces clavuligerus adpA-deleted mutant. Microbiology. 2010;156(8):2354–2365. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.035956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma M, Rateb ME, Teng QH, et al. Angucyclines and angucyclinones from Streptomyces sp. CB01913 featuring C-ring cleavage and expansion. J Nat Prod. 2015;78(10):2471–2480. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makino K, Amemura M, Kawamoto T, et al. DNA binding of PhoB and its interaction with RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1996;259(1):15–26. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao XM, Luo S, Zhou RC, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the daptomycin gene cluster in Streptomyces roseosporus by an autoregulator, AtrA. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(12):7992–8001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.608273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez-Hackert E, Stock AM. The DNA-binding domain of OmpR: crystal structures of a winged helix transcription factor. Structure. 1997;5(1):109–124. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(97)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore BS. Extending the biosynthetic repertoire in ribosomal peptide assembly. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47(49):9386–9388. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muth G, Nußbaumer B, Wohlleben W, et al. A vector system with temperature-sensitive replication for gene disruption and mutational cloning in streptomycetes. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219(3):341–348. doi: 10.1007/bf00259605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nett M, Ikeda H, Moore BS. Genomic basis for natural product biosynthetic diversity in the actinomycetes. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26(11):1362–1384. doi: 10.1039/b817069j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ochi K. Insights into microbial cryptic gene activation and strain improvement: principle, application and technical aspects. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2017;70:25–40. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohnishi Y, Kameyama S, Onaka H, et al. The A-factor regulatory cascade leading to streptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus: identification of a target gene of the A-factor receptor. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34(1):102–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okamoto-Hosoya Y, Okamoto S, Ochi K. Development of antibiotic-overproducing strains by site-directed mutagenesis of the rpsL gene in Streptomyces lividans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(7):4256–4259. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.7.4256-4259.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rebets Y, Ostash B, Luzhetskyy A, et al. Production of landomycins in Streptomyces globisporus 1912 and S. cyanogenus S136 is regulated by genes encoding putative transcriptional activators. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;222(1):149–153. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rebets Y, Ostash B, Luzhetskyy A, et al. DNA-binding activity of LndI protein and temporal expression of the gene that upregulates landomycin E production in Streptomyces globisporus 1912. Microbiology. 2005;151(1):281–290. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rebets Y, Dutko L, Ostash B, et al. Function of lanI in regulation of landomycin A biosynthesis in Streptomyces cyanogenus S136 and cross-complementation studies with Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory proteins encoding genes. Arch Microbiol. 2008;189(2):111–120. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staunton J, Weissman KJ. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18(4):380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka Y, Kasahara K, Hirose Y, et al. Activation and products of the cryptic secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters by rifampin resistance (rpoB) mutations in actinomycetes. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(13):2959–2970. doi: 10.1128/JB.00147-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang GJ, Hosaka T, Ochi K. Dramatic activation of antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor by cumulative drug resistance mutations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(9):2834–2840. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02800-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang TJ, Shan YM, Li H, et al. Multiple transporters are involved in natamycin efflux in Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10. Mol Microbiol. 2017;103(4):713–728. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang KQ, Han L, He JY, et al. A repressor-response regulator gene pair controlling jadomycin B production in Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230. Gene. 2001;279(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu P, Liu SP, Bu QT, et al. WblAch, a pivotal activator of natamycin biosynthesis and morphological differentiation in Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10, is positively regulated by AdpAch. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(22):6879–6887. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01849-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yushchuk O, Ostash I, Vlasiuk I, et al. Heterologous AdpA transcription factors enhance landomycin production in Streptomyces cyanogenus S136 under a broad range of growth conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(19):8419–8428. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou ZX, Xu QQ, Bu QT, et al. Genome mining-directed activation of a silent angucycline biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces chattanoogensis. ChemBioChem. 2015;16(3):496–502. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Strains and plasmids used in this study

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

1H and 13C NMR data of anthrachamycin in DMSO-d6(600 MHz)

Schematic representation of overlapping PCR strategy for introducing mutations into rpsL or rpoB

UV absorption of anthrachamycin

1H NMR spectrum of anthrachamycin

13C NMR spectrum of anthrachamycin

Distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer(DEPT135) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Correlated spectroscopy (COSY) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Nuclear overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Heavy mental binding capacity (HMBC) spectrum of anthrachamycin

Speculated mechanism for activating anthrachamycin biosynthesis