ABSTRACT

Background

To accurately assess micronutrient status, it is necessary to characterize the effects of inflammation and the acute-phase response on nutrient biomarkers.

Objective

Within a norovirus human challenge study, we aimed to model the inflammatory response of C-reactive protein (CRP) and α-1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) by infection status, model kinetics of micronutrient biomarkers by inflammation status, and evaluate associations between inflammation and micronutrient biomarkers from 0 to 35 d post–norovirus exposure.

Methods

Fifty-two healthy adults were enrolled into challenge studies in a hospital setting and followed longitudinally; all were exposed to norovirus, half were infected. Post hoc analysis of inflammatory and nutritional biomarkers was performed. Subjects were stratified by inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure. Smoothed regression models analyzed the kinetics of CRP and AGP by infection status, and nutritional biomarkers by inflammation. Linear mixed-effects models were used to analyze the independent relations between CRP, AGP, and biomarkers for iron, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin B-12, and folate from 0 to 35 d post–norovirus exposure.

Results

Norovirus-infected subjects had median (IQR) peak concentrations for CRP [16.0 (7.9–29.5) mg/L] and AGP [0.9 (0.8–1.2) g/L] on day 3 and day 4 postexposure, respectively. Nutritional biomarkers that differed (P < 0.05) from baseline within the inflamed group were ferritin (elevated day 3), hepcidin (elevated days 2, 3), serum iron (depressed days 2–4), transferrin saturation (depressed days 2–4), and retinol (depressed days 3, 4, and 7). Nutritional biomarker concentrations did not differ over time within the uninflamed group. In mixed models, CRP was associated with ferritin (positive) and serum iron and retinol (negative, P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Using an experimental infectious challenge model in healthy adults, norovirus infection elicited a time-limited inflammatory response associated with altered serum concentrations of certain iron and vitamin A biomarkers, confirming the need to consider adjustments of these biomarkers to account for inflammation when assessing nutritional status. These trials were registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00313404 and NCT00674336.

Keywords: micronutrients, acute-phase response, inflammation, norovirus challenge, kinetics

Introduction

Describing the relation between acute-phase proteins (APPs) and nutritional biomarkers in settings with high infectious disease burden is necessary for accurate assessment of micronutrient status (1). If underlying inflammation is ignored, iron and vitamin A status may be misclassified (2, 3). Within nationally representative surveys of children 6–59 mo old, misclassification ranged from underestimating iron deficiency by a median 25 percentage points (4) to overestimating vitamin A deficiency by a median 16 percentage points (5). Evaluation of nutrition programs or interventions may also be confounded by inflammation, specifically when they are combined with interventions targeted to reduce infection (6–8).

Currently, the only biomarker for which there is a consensus global guideline for adjustment in the context of inflammation is serum ferritin (9). The evidence base for adjusting nutritional biomarkers in the context of inflammation is limited to cross-sectional meta-analyses (10, 11), and a few longitudinal studies of adults undergoing surgery (12) or experiencing severe infections (13). Thus, an accurate assessment of micronutrient status depends on additional evidence quantifying time-varying interactions between nutritional biomarkers and infectious disease burden.

To assess patterns and interactions of inflammatory and nutritional biomarkers in response to an infectious challenge, we leveraged longitudinal data collected from 2 norovirus challenge trials (14, 15). Norovirus is the most common cause of diarrheal disease (16, 17), associated with 18% of diarrheal disease globally (18, 19). Although infections trigger an innate inflammatory response that temporarily alters circulating APPs (1, 11, 20), the kinetics of APPs triggered by exposure to norovirus has not been characterized. Iron and vitamin A biomarkers have been shown to be affected by subclinical levels of inflammation (5, 21–24), which may be better represented by the APP response to norovirus than a more severe infection, such as typhoid (13).

Our goal was to characterize the inflammatory response after a norovirus challenge, and to characterize the time-varying nutritional biomarker fluctuations by inflammatory response status. Our specific objectives were to model the kinetics of C-reactive protein (CRP) and α-1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) stratified by infection status, and to model the kinetics of micronutrient biomarkers [ferritin, hepcidin, serum iron, soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR), transferrin concentration, transferrin saturation, retinol-binding protein (RBP), retinol, 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], vitamin B-12, and folate] stratified by inflammation status. We hypothesized that CRP and AGP concentrations would differ by infection status, and that some micronutrient biomarker concentrations would differ by inflammation status resultant from norovirus exposure [ferritin ↑, hepcidin ↑, serum iron ↓, RBP ↓, retinol ↓, 25(OH)D ↓], whereas others would remain static (sTfR, vitamin B-12, and folate). We further evaluated the independent associations between CRP, AGP, and micronutrient biomarkers from 0 to 35 d postexposure.

Methods

Subjects and ethics

The serum assayed for this study was collected from apparently healthy adults that participated in 1 of 2 independent longitudinal norovirus challenge trials (NCT00313404 and NCT00674336) conducted at a Clinical Research Center in the United States between 2006 and 2009, and outcomes from those trials have been published (14, 15). The trials shared a common design and had similar protocols for specimen collection and participant assessment; however, they had different inoculum doses of 8FIIb Norwalk virus (HuNoV genogroup GI.1, ∼6.5 × 107 genomic equivalent copies per milliliter from 10 mL spiked groundwater or 1 × 104 genomic equivalent copies of virus from infected oysters) (14, 15). In brief, healthy volunteers were challenged with the virus, observed in controlled conditions in a hospital setting for 4 d, and then discharged with instructions to return on days 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 postchallenge. Serum was collected every day during the hospital stay and at each follow-up visit. Serum was stored in −80°C freezers for 7–10 y until they were shipped on dry ice to laboratories for the biomarker assessments of this study. Emory University Institutional Review Board approved both trials.

Of 64 enrolled volunteers, 26 became infected [norovirus was detectable in stool by real-time PCR (RT-PCR)] and among the infected 19 were symptomatic. A subsequent case-control study was conducted to describe the cytokine response patterns from norovirus exposure in 52 of the volunteers (25). We analyzed biomarkers from the same 52 subjects (age-matched, balanced by infection status) that had been sampled for the cytokine study (Supplemental Figure 1). The repeated-visits study design enabled assessing kinetics of CRP, AGP, and selected nutritional biomarkers. The nutritional biomarkers are ordered throughout the article in ascending order of existing evidence pertaining to their relation between nutrient and inflammation (1): iron [ferritin, hepcidin, iron, transferrin (receptor, saturation, and concentration)], vitamin A (RBP and retinol), vitamin D [25(OH)D], folate, and vitamin B-12.

Laboratory methods

Sandwich ELISA was used to measure CRP, AGP, ferritin, sTfR, and RBP at the VitMin laboratory (26). Serum hepcidin was quantified using the Hepcidin-25 (Bioactive) HS ELISA kit (DRG International, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol in a laboratory at Oxford University. Serum iron and transferrin concentrations were quantified using automated assays on an Abbott Architect c16000 automated analyzer (Abbott Laboratories) in the same lab that assessed hepcidin. Serum retinol (200 μL) was measured using HPLC in isocratic mode with 95:5 methanol:water (10 mM ammonium acetate) at 1 mL/min in a laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Serum 25(OH)D was measured using the Immunodiagnostic Systems iSYS chemiluminescent assay in a laboratory at Emory University participating in the vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme. Folate concentrations were measured in serum using the microbiological assay at the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional in Lima, Peru. Serum vitamin B-12 was analyzed using a Cobas e411 (Roche Diagnostics) with a competitive protein binding chemiluminescence immunoassay at the Western Human Nutrition Research Center in Davis, CA. Both the VitMin and Instituto de Investigación Nutricional laboratories participate in the US CDC's external laboratory quality assurance program VITAL-EQA (27).

Variable descriptions

All biomarkers were used as continuous variables in the kinetic modeling. Micronutrient and inflammation cutoffs were applied to define deficiency and to categorize subjects with inflammation due to norovirus exposure. The following cutoffs were applied: ferritin <15 µg/L (9), retinol <0.7 µmol/L (28), 25(OH)D <12 ng/mL (29), serum folate <10 nmol/L (30), vitamin B-12 <150 pmol/L (31), CRP >5 mg/L, and AGP >1 g/L (1). Binary clinical inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure was determined by comparing baseline (day 0, before norovirus exposure) CRP and AGP concentrations with days 1–3 CRP and AGP concentrations. Subjects with inflammatory biomarkers exceeding commonly used thresholds to define inflammation (CRP >5 mg/L or AGP >1 g/L) (1) on day 0 were considered inflamed at baseline. Those inflamed at baseline were excluded from analyses because our objective was to assess the effect of inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure. Clinical inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure was defined as CRP >5 mg/L or AGP >1 g/L at any time 1–3 d postexposure. Subjects were defined as symptomatic if after the norovirus exposure they experienced diarrhea, vomiting, or ≥1 of the following self-reported characteristics: nausea, abdominal cramps, headache, chills, myalgia, or fatigue (32).

Statistical analysis

All data processing and analyses were conducted in R version 3.4.3 (R Core Team) using the “dplyr,” “nlme,” “dunn.test,” and “ggplot2” packages. Baseline characteristics were compared across infection and inflammation status, separately, using χ2 and Kruskal–Wallis tests for categorical and continuous measures, respectively. To characterize the inflammatory response of norovirus infection, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare differences in median APP concentrations at days 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 35 by infection status. If any of the median tests indicated significant differences, then pairwise comparisons between each time point and baseline concentration were compared using Dunn's test with correction for multiple comparisons. To characterize the nutritional biomarker fluctuations by inflammatory response status, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare differences in median concentration of nutritional biomarkers at each time point postinfection, stratified by inflammation status. Similarly, Dunn's test was used to compare differences between baseline and time points that differed between inflamed and uninflamed groups. Concentrations of biomarkers over time were modeled using local regressions (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing) to provide a smoothed visual of temporal trends.

To evaluate the independent associations between APPs and each nutritional biomarker, we constructed time-lagged models of inflammation effects and autocorrelation of the prior measurement of nutritional biomarkers. All nutritional biomarkers were natural log–transformed to model these associations. Linear mixed-effect models were constructed for each nutritional biomarker outcome separately. The temporal effects and autocorrelation were explicitly modeled using time-lagged concentrations, i.e., CRPt−i,where t is the current measurement of a biomarker concentration and i represents a previous measure. Initially, autocorrelation was assessed within subjects using the function “acf” for ≤10 previous measurements. A majority of biomarkers had the strongest correlations within days 1–4; therefore, lagged variables were created and fit up to t − 4. Each model included all time points, and was fit using backwards selection through assessing model fit statistics, i.e., Akaike Information Criterion and log likelihood, coefficients, and SEs.

The full model took the form:

|

(1) |

where Yt is the nutritional biomarker concentration at measurement time t, α is the fixed intercept, θ is the subject random-effect intercept as N(τ2 = 0), and ε is the residual model error as N(σ2 = 0). The acute-phase inflammation biomarkers CRP and AGP are included at time t as CRPt and AGPt. Lags are denoted as subtractions from t, e.g., CRPt−3.

Results

Participant characteristics

One infected subject was dropped owing to incomplete data. The median (IQR) age of study subjects was 25 (21–28) y old, and baseline temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure indicated no evidence of acute illness. Baseline micronutrient deficiencies were absent for retinol (<0.7 µmol/L) and vitamin B-12 (<150 pmol/L). Six percent of subjects had folate deficiency (<10 nmol/L), 14% were at risk of vitamin D deficiency [25(OH)D <12 ng/mL], and 16% had low iron stores (serum ferritin <15 μg/L). Median vitamin B-12 concentration at baseline was significantly higher among subjects that became infected with norovirus than among noninfected subjects (Supplemental Table 1). Baseline nutritional profiles and APP concentrations did not differ between subjects stratified by clinical inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of norovirus challenge subjects, stratified by inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure1

| Uninflamed (n = 24) | Inflamed2 (n = 21) | Inflamed at baseline (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 24.0 (20.8–27.0) | 26.0 (22.0–28.0) | 23.5 (23.0–36.0) |

| Female | 64 | 57 | 33 |

| Inflammation | |||

| CRP, mg/L | 1.0 (0.5–1.5) | 0.6 (0.3–1.8) | 8.0 (5.2–10.2) |

| AGP, g/L | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.6 (0.4–0.7) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) |

| Nutrition | |||

| Ferritin, µg/L | 50.8 (15.4–96.9) | 65.0 (34.1–107.0) | 58.3 (54.3–78.6) |

| Hepcidin, ng/mL | 5.9 (2.0–15.0) | 10.0 (7.6–17.4) | 12.2 (9.6–13.4) |

| Serum iron, µmol/L | 12.4 (10.6–17.8) | 15.2 (12.2–19.1) | 8.5 (8.1–11.9) |

| sTfR, mg/L | 5.1 (4.1–6.7) | 5.0 (4.2–5.6) | 5.0 (4.5–5.4) |

| Transferrin, g/L | 2.7 (2.5–3.3) | 2.7 (2.5–2.9) | 2.9 (2.7–3.2) |

| TSAT, % | 20.0 (16.1–30.7) | 27.6 (21.3–31.7) | 13.5 (12.5–21.6) |

| RBP, µmol/L | 1.7 (1.6–2.0) | 1.9 (1.8–2.2) | 2.2 (1.9–2.4) |

| Retinol, µmol/L | 1.3 (1.0–1.4) | 1.3 (1.2–1.6) | 1.6 (1.1–1.7) |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 20.2 (14.9–27.4) | 20.0 (17.4–23.0) | 22.4 (16.0–24.8) |

| Vitamin B-12, pmol/L | 315.3 (269.9–388.5) | 467.8 (307.9–609.1) | 315.2 (277.6–329.6) |

| Folate, ng/mL | 14.3 (8.6–18.8) | 12.9 (10.2–21.3) | 6.1 (4.4–16.9) |

| Vital signs | |||

| Temp, °C | 36.6 (36.1–36.7) | 36.0 (36.0–36.8) | 36.8 (36.5–37.0) |

| Pulse, bpm | 72 (66–78) | 71 (63–83) | 76 (67–77) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 73 (67–80) | 69 (59–76) | 71 (68–81) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 115 (110–124) | 116 (111–123) | 129 (114–135) |

| Respiration, brpm | 18 (18–18)* | 16 (16–18)* | 18 (18–18) |

n = 51. Values are median (IQR) or %. *Significant at α < 0.05 using either χ2 or Kruskal–Wallis test to compare inflamed and uninflamed subjects for categorical and continuous data, respectively. AGP, α-1-acid glycoprotein; bpm, beats per minute; brpm, breaths per minute; CRP, C-reactive protein; RBP, retinol-binding protein; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; TSAT, transferrin saturation; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

Clinical inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure was defined as CRP >5 mg/L or AGP >1 g/L at any time 1–3 d postexposure, given CRP ≤ 5 mg/L and AGP ≤ 1 g/L on day 0.

Six subjects with inflammatory biomarkers above thresholds commonly used to define inflammation at baseline (4 with elevated CRP, 2 with elevated AGP) were excluded from all analyses beyond the descriptive statistics. Clinical inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure did not correlate perfectly with norovirus infection, defined by norovirus detectable in stool by RT-PCR. The majority of subjects that demonstrated clinical inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure were infected with norovirus (n = 20 of 21, or 95%; Table 2). However, of the 24 noninflamed subjects, 3 people were norovirus infected (detectable in stool by RT-PCR), although they were asymptomatic.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of subject classifications for inflamed, norovirus infected, and symptomatic within a norovirus human challenge study1

| Inflamed | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Yes | No | Total |

| Norovirus infected and symptomatic | 16 | 0 | 16 |

| Norovirus infected and asymptomatic | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Norovirus uninfected and symptomatic | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Norovirus uninfected and asymptomatic | 1 | 19 | 20 |

| Total | 21 | 24 | 45 |

Inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure was defined as CRP >5 mg/L or AGP >1 g/L at any time 1–3 d postexposure, given CRP ≤5 mg/L and AGP ≤1 g/L on day 0. Six subjects were excluded based on CRP >5 mg/L or AGP >1 g/L on day 0. Norovirus infection was defined as norovirus detectable in stool by real-time PCR. Symptomatic was defined as diarrhea, vomiting, or ≥1 of the following self-reported characteristics: nausea, abdominal cramps, headache, chills, myalgia, or fatigue. AGP, α-1-acid glycoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

APP response to norovirus infection

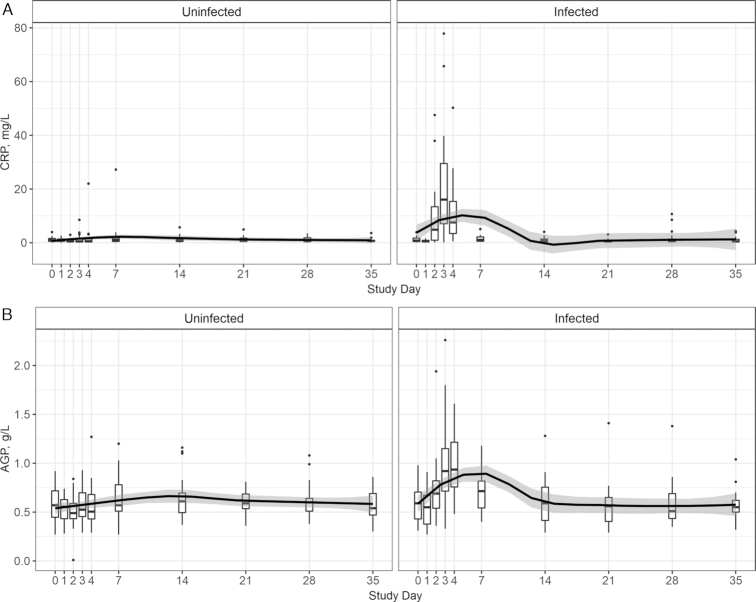

The inflammatory response of CRP and AGP serum concentrations was modeled by norovirus infection status. There were similarities between CRP and AGP peak concentrations as well as normalization time among norovirus-infected individuals (Figure 1). CRP peaked with a median (IQR) concentration of 16.0 (7.9–29.5) mg/L at day 3, and AGP peaked at 0.9 (0.8–1.2) g/L at day 4 for the infected group. At day 3, both APPs were significantly different from the uninfected group (CRP: χ2K–W = 21.5, P < 0.01; AGP: χ2K–W = 4.6, P < 0.01). CRP and AGP medians of the infected group were indistinguishable from the uninfected group by day 7 (χ2K–W = 1.5, P = 0.21; χ2K–W = 1.0, P = 0.30). Within the uninfected group, neither CRP nor AGP concentrations deviated from baseline (χ2K–W = 6.9, P = 0.64; χ2K–W = 11.3, P = 0.24) over the study course (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Baseline (day 0) to day 35 postexposure CRP (A) and AGP (B) measurements plotted using box and whiskers, displaying median and IQR (box range) with whiskers representing 1.5 × the 25% and 75% quartile and outliers depicted by dots (n = 45 subjects with repeated measures). Pairwise differences between baseline and other days within infection grouping tested using Dunn's test. Box plot locally estimated scatterplot smoothing fit with 95% prediction interval in black and gray banding. AGP, α-1-acid glycoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Nutritional biomarker responses to inflammation caused by norovirus exposure

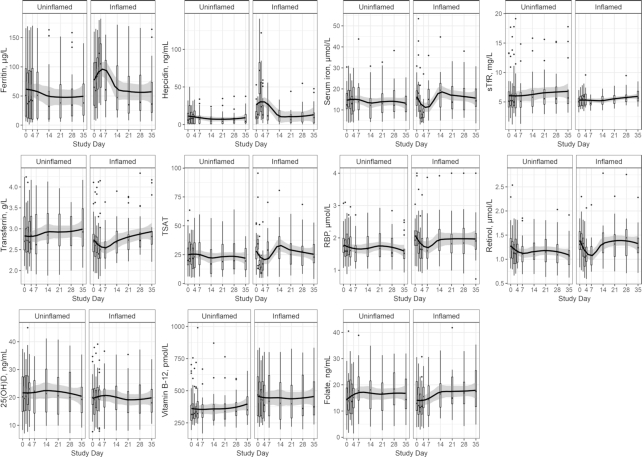

The kinetics of micronutrient biomarkers [ferritin, hepcidin, serum iron, sTfR, transferrin concentration, transferrin saturation, RBP, retinol, 25(OH)D, folate, and vitamin B-12] were stratified by clinical inflammation resulting from norovirus exposure. Concentrations of the following nutrient biomarkers differed significantly compared with baseline concentrations among subjects that experienced inflammation from norovirus exposure: ferritin (elevated day 3, P < 0.05), hepcidin (elevated days 2–3, P < 0.01), serum iron (depressed days 2–4, P < 0.01), transferrin saturation (depressed days 2–4, day 2 P < 0.05, day 3–4 P < 0.01), and retinol (depressed days 3, 4, and 7, P < 0.05; Figure 2). Although fluctuations in concentrations of the remaining nutritional biomarkers can be observed visually, there were no time points that differed in statistical significance from baseline concentration for sTfR, transferrin concentration, RBP, 25(OH)D, folate, or vitamin B-12 among the inflamed group (Figure 2). Among the uninflamed group, regardless of infection status, no nutritional biomarkers had concentrations that were statistically significantly different from baseline.

FIGURE 2.

Baseline (day 0) to day 35 postexposure nutritional biomarker measurements plotted using box and whiskers, displaying median and IQR (box range) with whiskers representing 1.5 × the 25% and 75% quartile and outliers depicted by dots (n = 45 subjects with repeated measures). Pairwise differences between baseline and other days within infection grouping tested using Dunn's test. Box plot locally estimated scatterplot smoothing fit with 95% prediction interval in black and grey banding. RBP, retinol-binding protein; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; TSAT, transferrin saturation; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

Independent effects of inflammation on nutritional biomarkers

Based on the most conservative models, adjusting for lagged inflammation effects and autocorrelation of the prior measurement of nutritional biomarkers for all subjects across time (Yt−1), ferritint, serum iront, sTfRt, retinolt, RBPt, and vitamin B-12t were independently associated with CRPt or AGPt (Table 3). The iron biomarkers ferritint (β: 0.11; 95% CI: 0.06, 0.15) and serum iront (β: −0.10; 95% CI: −0.19, −0.01) were significantly associated with CRPt. sTfRt was significantly positively associated with AGPt (0.10; 95% CI: 0.08, 0.13) and negatively associated with CRPt (β: −0.06; 95% CI: −0.08, −0.03). The vitamin A biomarkers retinolt (β: −0.05; 95% CI: −0.07, −0.04) and RBPt (β: −0.07; 95% CI: −0.09, −0.05) were significantly negatively associated with CRPt. RBPt was also significantly positively associated with AGPt (β: 0.04; 95% CI: 0.02, 0.06). Vitamin B-12t was significantly positively and negatively associated, respectively, with AGPt (β: 0.03; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.05) and CRPt (β: −0.02; 95% CI: −0.04, −0.003) (Table 3). The coefficients for the lagged inflammation effects are included in Supplemental Table 2.

TABLE 3.

Time t β (95% CI) estimates of associations between inflammatory markers and nutritional biomarkers, accounting for measurements at all times and the lagged effects of inflammation1

| Yt | CRPt | AGPt | Yt− 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferritin | 0.11 (0.06, 0.15)* | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) | 0.91 (0.865, 0.95)* |

| Hepcidin | 0.09 (−0.13, 0.30) | 0.06 (−0.09, 0.21) | 0.54 (0.43, 0.64)* |

| Serum iron | −0.10 (−0.19, −0.01)* | — | 0.24 (0.12, 0.35)* |

| sTfR | −0.06 (−0.08, −0.03)* | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13)* | 0.15 (0.05, 0.25)* |

| Transferrin | −0.001 (−0.02, 0.02) | — | 0.89 (0.83, 0.95)* |

| TSAT | −0.08 (−0.17, 0.02) | — | 0.225 (0.105, 0.34)* |

| RBP | −0.07 (−0.09, −0.05)* | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06)* | 0.29 (0.19, 0.385)* |

| Retinol | −0.05 (−0.07, −0.04)* | — | 0.26 (0.16, 0.36)* |

| 25(OH)D | — | 0.03 (0.00, 0.05) | 0.18 (0.07, 0.30)* |

| Vitamin B-12 | −0.02 (−0.04, −0.003)* | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05)* | 0.84 (0.79, 0.89)* |

| Folate | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.485 (0.40, 0.57)* |

Modeling ln(Yt) = α + θ + CRPt + CRPt−1 + CRPt−2 + CRPt−3 + CRPt−4 + AGPt + AGPt−1 + AGPt−2 + AGPt−3 + AGPt−4 + ln(Yt−1) + ε; where Yt is the nutritional biomarker concentration at measurement time t, α is the fixed intercept, θ is the subject random-effect intercept as N(τ2 = 0), and ε is the residual model error as N(σ2 = 0). The inflammation biomarkers CRP and AGP are included at time t as CRPt and AGPt as well as lagged terms up to t − 4. Values are standardized β (95% CI) for CRPt and AGPt. Models adjusted for subject and temporal effects using mixed effects. CRPt−1, CRPt−2, and AGPt−4 were not included in any final models. *Significant at α < 0.05; n = 45 subjects at 10 time points. Supplemental Table 2 presents β (95% CI) estimates for the lagged inflammation variables. AGP, α-1-acid glycoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein; RBP, retinol-binding protein; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; TSAT, transferrin saturation; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; —, term was not included in the final model.

Discussion

Using an experimental infectious challenge model, we have demonstrated a clear causative, time-limited relation between acute inflammation and perturbations in micronutrient biomarkers of iron and vitamin A status, confirming the need to consider adjustments of these biomarkers to account for inflammation when assessing nutritional status. Norovirus induced an inflammatory response (demonstrated by elevations in CRP and AGP) 3–4 d after exposure, which caused elevations in serum ferritin and hepcidin, and reductions in serum iron and retinol, concentrations. These perturbations were supported by the independent positive association between ferritin and CRP, and the independent negative associations between serum iron, retinol, and CRP in linear mixed models. No nutritional biomarker perturbations were observed over the 35-d study duration among uninflamed subjects, further supporting that the concentration changes seen among the inflamed group were likely artificial and not reflecting true nutrition status alterations.

Inflammatory protein response to norovirus infection

CRP has been described as the “first line of innate host defense” for decades (33–36). Although animal models have characterized CRP kinetics (37), there are limited studies in humans. Furthermore, most investigations have modeled CRP kinetics under extreme conditions, such as surgeries (12, 38). As evident from recent meta-analyses, nutritional biomarkers are affected by even low levels of inflammation in both high and low infection burden settings (5, 21–24), raising the question of APP patterns during common, self-limiting infections. In our trial, norovirus infection triggered an acute-phase response as indicated by median peak concentrations of 16.0 mg CRP/L at day 3 postexposure, >3 times the usual CRP cutoff (5 mg/L). However, the median peak concentration of AGP (0.9 g/L) at day 4 was lower than the traditionally used cutoff of AGP of 1 g/L. In a controlled typhoid experiment among apparently healthy adults, CRP peaked 2 d after diagnosis, with a median concentration >100 mg/L (13). Two to 3 d after elective orthopedic surgery, CRP reached a maximum concentration, ranging from 48 to 140 mg/L (38). CRP has demonstrated increases >1000-fold post–inflammatory stimuli (39). Evidence of AGP kinetics during infection or in response to tissue injury is limited, compared with CRP. However, there has been a general recognition that AGP rises more slowly than CRP and stays elevated for a longer period of time (40), although this pattern was not observed in this study.

Nutritional biomarker responses to inflammation caused by norovirus exposure

Although the kinetics we observed for CRP and AGP in response to norovirus infection were distinct from typical thresholds used to describe the acute-phase response (10, 22, 41, 42), the iron and vitamin A responses to inflammation were as hypothesized. Marked reductions in circulating iron (serum iron and transferrin saturation) (43–45) were likely caused by the observed induction of the hormonal iron regulator, hepcidin, and the iron storage protein ferritin also increased. The hepcidin concentration peaked (day 2 postexposure) before the ferritin peak (day 3 postexposure). Similar to other APPs, hepcidin is upregulated during the innate response to infection via the IL6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway (46, 47). An increase in hepcidin concentrations after pathogen exposure has been likewise demonstrated in other human infection challenge studies, including typhoid (13) and malaria (48, 49). The vitamin A biomarkers, RBP and retinol, demonstrated similar responses to inflammation: retinol concentrations were statistically lower than baseline on days 3, 4, and 7 post–exposure to norovirus, and RBP followed a similar pattern that was observed visually, but was not statistically significant, possibly owing to small sample size or a modest inflammatory response. This depression of vitamin A biomarkers coinciding with elevated inflammatory proteins has been demonstrated in numerous studies (50–52). Concentrations of sTfR, transferrin, 25(OH)D, folate, and vitamin B-12 did not differ over time within the inflamed group. Among the uninflamed group, none of the nutritional biomarker concentrations differed over time, indicating that the nutritional biomarker perturbations seen among the inflamed group were likely artificial and not reflecting true nutrition status alterations.

The lower vitamin B-12 concentrations at baseline that appeared protective of norovirus infection may have a genetic explanation, such as a single nucleotide polymorphism. Although secretor-positive adults were enrolled into these challenge studies (32), genetic variants of fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) have been associated with lower vitamin B-12 status (53, 54). Homozygous FUT2 nonsecretor genotype is characterized as resistant to norovirus infection (55, 56).

Independent effects of inflammation on nutritional biomarkers

The independent associations of ferritin, serum iron, and retinol with CRP at time t support the causal framework that inflammation affects iron and vitamin A metabolism. However, the combination of assessing CRP and AGP simultaneously adds complexity to this analysis and interpretation. For example, sTfR, RBP, and vitamin B-12 all had significant direct associations with CRP and significant inverse associations with AGP at time t, possibly due to distinct roles of the APPs that result in nutrient sequestration that varies across time. As demonstrated by Wessells et al. (57), accounting for the temporal effects of inflammation resulted in more subtle corrections for inflammation than cross-section–based techniques. Having access to repeated measures on individuals within surveys to estimate the effects of inflammation on micronutrient biomarkers may be rare, but additional analysis of existing cohort data sets that contain nutrition and inflammation biomarkers would help elucidate these complex interactions.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is one of the first to assess dynamic changes in inflammation and micronutrient biomarkers after an experimental enteric viral challenge. We quantified the kinetics of APPs given norovirus infection, and the subsequent effects of inflammation on nutrient biomarkers, providing clear indication that nutrient biomarkers fluctuate during relatively mild infections among adults. The strengths of this analysis were the repeated-measures design and the controlled norovirus challenge with serum samples utilized at 10 time points. A limitation of this analysis was that results from adults cannot be directly transferred to children. The population group of highest concern for nutritional status misclassification and norovirus infections are children <5 y of age; however, our challenge studies were performed on apparently healthy adults. The immune system maturation likely influences the inflammation and nutritional biomarker kinetic response to norovirus exposure. Therefore, patterns might be more pronounced in children. Another limitation was the small sample size. In some cases such as RBP, changes in nutritional biomarker concentrations seemed apparent graphically, yet the studies were likely underpowered and did not reach statistical significance. The inflammation lag terms in the linear mixed model may have been easier to interpret within a larger sample as well.

Conclusions

The confounding effects of inflammation on micronutrient biomarkers have been identified as a critical research gap (1), and efforts to adjust nutrition biomarkers for inflammation have been limited to cross-sectional data (11, 22, 42, 58). This study demonstrates that some people exposed to norovirus do not experience virus in their stools or elevated APPs. Inflammation from norovirus affects the measurement concentrations of some iron and vitamin A biomarkers, and therefore should be interpreted accordingly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We recognize input from Dr Christine Clewes, PhD, independent consultant on the interpretation of results.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—AMW, JSL, BAL, PSS, and RCF-A: conceptualized this research; AMW and CNL: had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; VT, RDW, SAT, AEA, AM, S-RP, SS-F, KW, and LA: all assisted in laboratory analysis and interpretation of the results; DT: provided insights on the interpretation of the results; and all authors: read the manuscript and provided intellectual content. None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study.

Notes

Supported by a Robert W Woodruff Health Sciences Center Fund, Inc. synergy award (to AMW, PSS, and BAL); the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, USDA, under awards 2011-68003-30395 (NoroCORE, Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant) (to JSL) and 2015-67017-23080 (to JSL); and the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity at the US CDC.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations used: AGP, α-1-acid glycoprotein; APP, acute-phase protein; CRP, C-reactive protein; FUT2, fucosyltransferase 2; RBP, retinol-binding protein; RT-PCR, real-time PCR; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

References

- 1. Raiten DJ, Sakr Ashour FA, Ross AC, Meydani SN, Dawson HD, Stephensen CB, Brabin BJ, Suchdev PS, van Ommen B; INSPIRE Consultative Group. Inflammation and Nutritional Science for Programs/Policies and Interpretation of Research Evidence (INSPIRE). J Nutr. 2015;145(5):1039S–108S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown KH, Lanata CF, Yuen ML, Peerson JM, Butron B, Lönnerdal B. Potential magnitude of the misclassification of a population's trace element status due to infection: example from a survey of young Peruvian children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58(4):549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diana A, Haszard JJ, Purnamasari DM, Nurulazmi I, Luftimas DE, Rahmania S, Nugraha GI, Erhardt J, Gibson RS, Houghton L. Iron, zinc, vitamin A and selenium status in a cohort of Indonesian infants after adjusting for inflammation using several different approaches. Br J Nutr. 2017;118(10):830–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Suchdev PS, Williams AM, Mei Z, Flores-Ayala R, Pasricha SR, Rogers LM, Namaste SM. Assessment of iron status in settings of inflammation: challenges and potential approaches. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 6):1626S–33S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Larson LM, Namaste SM, Williams AM, Engle-Stone R, Addo OY, Suchdev PS, Wirth JP, Temple V, Serdula M, Northrop-Clewes CA. Adjusting retinol-binding protein concentrations for inflammation: Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 1):390S–401S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dangour AD, Watson L, Cumming O, Boisson S, Che Y, Velleman Y, Cavill S, Allen E, Uauy R. Interventions to improve water quality and supply, sanitation and hygiene practices, and their effects on the nutritional status of children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD009382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cichon B, Fabiansen C, Iuel-Brockdorf AS, Yaméogo CW, Ritz C, Christensen VB, Filteau S, Briend A, Michaelsen KF, Friis H. Impact of food supplements on hemoglobin, iron status, and inflammation in children with moderate acute malnutrition: a 2 × 2 × 3 factorial randomized trial in Burkina Faso. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(2):278–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stewart CP, Dewey KG, Lin A, Pickering AJ, Byrd KA, Jannat K, Ali S, Rao G, Dentz HN, Kiprotich M et al.. Effects of lipid-based nutrient supplements and infant and young child feeding counseling with or without improved water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) on anemia and micronutrient status: results from 2 cluster-randomized trials in Kenya and Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(1):148–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO. Serum ferritin concentrations for the assessment of iron status and iron deficiency in populations. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thurnham DI, Northrop-Clewes CA, Knowles J. The use of adjustment factors to address the impact of inflammation on vitamin A and iron status in humans. J Nutr. 2015;145(5):1137S–43S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Suchdev PS, Namaste SM, Aaron GJ, Raiten DJ, Brown KH, Flores-Ayala R; BRINDA Working Group. Overview of the Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(2):349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Louw JA, Werbeck A, Louw ME, Kotze TJ, Cooper R, Labadarios D. Blood vitamin concentrations during the acute-phase response. Crit Care Med. 1992;20(7):934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Darton TC, Blohmke CJ, Giannoulatou E, Waddington CS, Jones C, Sturges P, Webster C, Drakesmith H, Pollard AJ, Armitage AE. Rapidly escalating hepcidin and associated serum iron starvation are features of the acute response to typhoid infection in humans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(9):e0004029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leon JS, Kingsley DH, Montes JS, Richards GP, Lyon GM, Abdulhafid GM, Seitz SR, Fernandez ML, Teunis PF, Flick GJ et al.. Randomized, double-blinded clinical trial for human norovirus inactivation in oysters by high hydrostatic pressure processing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(15):5476–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seitz SR, Leon JS, Schwab KJ, Lyon GM, Dowd M, McDaniels M, Abdulhafid G, Fernandez ML, Lindesmith LC, Baric RS et al.. Norovirus infectivity in humans and persistence in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(19):6884–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Platts-Mills JA, Babji S, Bodhidatta L, Gratz J, Haque R, Havt A, McCormick BJ, McGrath M, Olortegui MP, Samie A et al.. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(9):e564–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirk MD, Pires SM, Black RE, Caipo M, Crump JA, Devleesschauwer B, Döpfer D, Fazil A, Fischer-Walker CL, Hald T et al.. World Health Organization estimates of the global and regional disease burden of 22 foodborne bacterial, protozoal, and viral diseases, 2010: a data synthesis. PLoS Med. 2015;12(12):e1001921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lopman BA, Steele D, Kirkwood CD, Parashar UD. The vast and varied global burden of norovirus: prospects for prevention and control. PLoS Med. 2016;13(4):e1001999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahmed SM, Hall AJ, Robinson AE, Verhoef L, Premkumar P, Parashar UD, Koopmans M, Lopman BA. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):725–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wieringa FT, Dijkhuizen MA, West CE, Northrop-Clewes CA, Muhilal. Estimation of the effect of the acute phase response on indicators of micronutrient status in Indonesian infants. J Nutr. 2002;132(10):3061–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Namaste SM, Rohner F, Huang J, Bhushan NL, Flores-Ayala R, Kupka R, Mei Z, Rawat R, Williams AM, Raiten DJ et al.. Adjusting ferritin concentrations for inflammation: Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 1):359S–71S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thurnham DI, McCabe LD, Haldar S, Wieringa FT, Northrop-Clewes CA, McCabe GP. Adjusting plasma ferritin concentrations to remove the effects of subclinical inflammation in the assessment of iron deficiency: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):546–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thurnham DI, McCabe GP, Northrop-Clewes CA, Nestel P. Effects of subclinical infection on plasma retinol concentrations and assessment of prevalence of vitamin A deficiency: meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;362(9401):2052–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rohner F, Namaste SM, Larson LM, Addo OY, Mei Z, Suchdev PS, Williams AM, Sakr Ashour FA, Rawat R, Raiten DJ et al.. Adjusting soluble transferrin receptor concentrations for inflammation: Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 1):372S–82S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Newman KL, Moe CL, Kirby AE, Flanders WD, Parkos CA, Leon JS. Human norovirus infection and the acute serum cytokine response. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;182(2):195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erhardt JG, Estes JE, Pfeiffer CM, Biesalski HK, Craft NE. Combined measurement of ferritin, soluble transferrin receptor, retinol binding protein, and C-reactive protein by an inexpensive, sensitive, and simple sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique. J Nutr. 2004;134(11):3127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haynes B, Schleicher R, Jain R, Pfeiffer C. The CC VITAL-EQA program, external quality assurance for serum retinol, 2003–2006. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;390(1–2):90–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. WHO. Serum retinol concentrations for determining the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. WHO. Serum and red blood cell folate concentrations for assessing folate status in populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Benoist B. Conclusions of a WHO Technical Consultation on folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Newman KL, Moe CL, Kirby AE, Flanders WD, Parkos CA, Leon JS. Norovirus in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals: cytokines and viral shedding. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;184(3):347–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Volanakis JE. Human C-reactive protein: expression, structure, and function. Mol Immunol. 2001;38(2–3):189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pepys MB. C-reactive protein fifty years on. Lancet. 1981;317(8221):653–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gewurz H. Biology of C-reactive protein and the acute phase response. Hosp Pract (Hosp Ed). 1982;17(6):67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gewurz H, Mold C, Siegel J, Fiedel B. C-reactive protein and the acute phase response. Adv Intern Med. 1982;27:345–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Torzewski M, Waqar AB, Fan J. Animal models of C-reactive protein. Mediators Inflamm. 2014:683598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Larsson S, Thelander U, Friberg S. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels after elective orthopedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Slaats J, Ten Oever J, van de Veerdonk FL, Netea MG. IL-1β/IL-6/CRP and IL-18/ferritin: distinct inflammatory programs in infections. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(12):e1005973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thurnham DI. Interactions between nutrition and immune function: using inflammation biomarkers to interpret micronutrient status. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thurnham DI, Northrop-Clewes CA. Inflammation and biomarkers of micronutrient status. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19(6):458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thurnham DI. Correcting nutritional biomarkers for the influence of inflammation. Br J Nutr. 2017;118(10):761–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ganz T. Iron and infection. Int J Hematol. 2018;107(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ross AC. Impact of chronic and acute inflammation on extra- and intracellular iron homeostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 6):1581S–7S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prentice AM, Ghattas H, Cox SE. Host-pathogen interactions: can micronutrients tip the balance?. J Nutr. 2007;137(5):1334–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nemeth E, Valore EV, Territo M, Schiller G, Lichtenstein A, Ganz T. Hepcidin, a putative mediator of anemia of inflammation, is a type II acute-phase protein. Blood. 2003;101(7):2461–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood. 2006;108(9):3204–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. de Mast Q, van Dongen-Lases EC, Swinkels DW, Nieman AE, Roestenberg M, Druilhe P, Arens TA, Luty AJ, Hermsen CC, Sauerwein RW et al.. Mild increases in serum hepcidin and interleukin-6 concentrations impair iron incorporation in haemoglobin during an experimental human malaria infection. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(5):657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Spottiswoode N, Armitage AE, Williams AR, Fyfe AJ, Biswas S, Hodgson SH, Llewellyn D, Choudhary P, Draper SJ, Duffy PE et al.. Role of activins in hepcidin regulation during malaria. Infect Immun. 2017;85(12):e00191–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Galloway P, McMillan DC, Sattar N. Effect of the inflammatory response on trace element and vitamin status. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000;37(Pt 3):289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Larson LM, Addo OY, Sandalinas F, Faigao K, Kupka R, Flores-Ayala R, Suchdev PS. Accounting for the influence of inflammation on retinol-binding protein in a population survey of Liberian preschool-age children. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(2):e12298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Larson LM, Guo J, Williams AM, Young MF, Ismaily S, Addo OY, Thurnham D, Tanumihardjo SA, Suchdev PS, Northrop-Clewes CA. Approaches to assess vitamin A status in settings of inflammation: Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):E1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hazra A, Kraft P, Selhub J, Giovannucci EL, Thomas G, Hoover RN, Chanock SJ, Hunter DJ. Common variants of FUT2 are associated with plasma vitamin B12 levels. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1160–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Allin KH, Friedrich N, Pietzner M, Grarup N, Thuesen BH, Linneberg A, Pisinger C, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Sandholt CH. Genetic determinants of serum vitamin B12 and their relation to body mass index. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(2):125–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD, Cannon JL, Zheng DP, Vinje J, Baric RS. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med. 2008;5(2):e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Larsson MM, Rydell GE, Grahn A, Rodríguez-Díaz J, Åkerlind B, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Larson G, Svensson L. Antibody prevalence and titer to norovirus (genogroup II) correlate with secretor (FUT2) but not with ABO phenotype or Lewis (FUT3) genotype. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(10):1422–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wessells KR, Peerson JM, Brown KH. Within-individual differences in plasma ferritin, retinol-binding protein, and zinc concentrations in relation to inflammation observed during a short-term longitudinal study are similar to between-individual differences observed cross-sectionally. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1484–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Namaste SML, Aaron GJ, Varadhan R, Peerson JM, Suchdev PS. Methodological approach for the Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 1):333S–47S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.