Abstract

Introduction:

Using a prospective longitudinal design across six years, the current study investigated whether adolescents’ experiences of peer rejection across middle school increased their risk of maladaptive (aggressive and unsupportive) behaviors in high school romantic relationships. Additionally, friendship quality following the transition to high school was examined as a potential protective factor.

Methods:

The sample consisted of 1,987 ethnically diverse youth (54% female; Mage=17.10) who were romantically involved at eleventh grade. Peer rejection (based on peer nominations) was assessed at four time points across three years in middle school. Students reported on their friendship quality in ninth grade and their aggressive (e.g., shouting; hitting) and supportive (e.g., listening; helping) behaviors towards a romantic partner in eleventh grade.

Results:

Results demonstrated that adolescents who were increasingly rejected by peers during middle school were more likely to behave aggressively towards their romantic partners in high school. Friendship quality at the beginning of high school moderated prospective links from rejection to support, such that escalating middle school peer rejection predicted less supportive romantic behaviors only among youth with low-quality friendships at ninth grade. These patterns were documented over and above the effects of sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and students’ aggressive behavior at the beginning of middle school.

Conclusions:

Together, the findings suggest that 1) increasing peer rejection during middle school may spiral into later romantic relationship dysfunction and 2) supportive friendships across a critical school transition can interrupt links between peer and romantic problems.

Keywords: peer rejection, romantic relationships, dating aggression, friendship quality, adolescence, longitudinal

Establishing healthy romantic relationships is considered a key developmental task of adolescence (Collins & van Dulmen, 2006; Furman, 2002), with the majority of teens reporting at least one romantic relationship by age 15 (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003). Although early relationships provide opportunities for adolescents to experience companionship, intimacy, and support that offer preparation for healthy romantic bonds in adulthood, they can also present unique developmental challenges. In particular, adolescents’ inexperience communicating with a romantic partner or managing the intense emotions of a romantic relationship can precipitate problematic interpersonal functioning. Indeed, up to 35% of adolescents exhibit aggression towards their dating partners (Haynie et al., 2013), and many young people feel ill-equipped to navigate romantic conflicts and foster caring intimate relationships (Weissbourd, Anderson, Cashin, & McIntyre, 2017). Because aggression and hostility in teenagers’ romantic relationships are concerning developmental precursors to adult intimate partner violence (Exner-Cortens, Eckenrode, & Rothman, 2013), adolescence may provide a unique window of opportunity to identify risk and protective factors for romantic dysfunction.

Developmentally, peer relationships provide a central context for the progression of adolescents’ romantic relationships (Furman, 1999) and meaningfully shape their romantic experiences in both negative and positive ways (Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000; van de Bongardt, Yu, Deković, & Meeus, 2015). Whereas repeated exposure to peer stressors, such as chronic rejection, is likely to amplify maladaptive romantic behaviors (Garthe, Sullivan, & McDaniel, 2016), access to positive peer relationships (e.g., high quality friendships) may serve a vital function in preparing adolescents for healthy intimate relationships (Linder & Collins, 2005). Despite increased empirical interest in identifying peer relationship predictors of romantic outcomes, the scarcity of prospective longitudinal studies limits our understanding of developmental pathways from one relational context to the other. Capitalizing on six years of longitudinal data, the current study investigates whether adolescents’ experiences of peer rejection in middle school predict their aggressive and (un)supportive behaviors toward their romantic partners in high school, over and above baseline aggression. We also examine ninth grade friendship quality as a moderator of these links to determine if having close, caring friends at a critical turning point—the high school transition—can protect against the negative legacy of middle school peer rejection.

Peer Rejection as a Risk Factor

Across the transition to adolescence, peer rejection emerges as a common and consequential form of negative treatment (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990). At a time when the need for peer approval is heightened (Brown, 1990), the experience of being disliked or avoided by peers can take a toll on adolescents’ social-emotional adjustment (Juvonen, 2013). Although rejection may function as a marker of youth’s pre-existing behavioral problems (e.g., aggression), the experience of peer rejection independently contributes to future maladjustment over and above other individual risk factors (Zimmer-Gembeck, 2016).

Being disliked by peers impairs adolescents’ ability to successfully navigate other interpersonal relationships. Because positive peer interactions offer opportunities to acquire important interpersonal competencies (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Ladd, 1999), adolescents who are shunned by peers lack access to a key context for practicing social skills (Juvonen, 2013). Indeed, compared to their well-liked peers, rejected youth are less sociable (Bierman & Montminy, 1993; Newcomb, Bukowski, & Pattee, 1993) and exhibit more interpersonal problem-solving difficulties (Dodge et al., 2003). Additionally, when peers repeatedly communicate messages of rejection, adolescents come to anxiously anticipate social rejection in the future (Downey, Bonica, & Rincón, 1999) and exhibit other social-information processing deficits (e.g., hostile attributions; approval of aggression; Crick & Dodge, 1994; Pettit, Lansford, Malone, Dodge, & Bates, 2010) that may contribute to further relationship difficulties (Zimmer-Gembeck, 2016). Adolescents who expect rejection, for example, are more likely to behave aggressively (e.g., in response to possible threats; Zimmer-Gembeck, Nesdale, Webb, Khatibi, & Downey, 2016), which in turn exacerbates peer disliking (Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003). Thus, by depriving adolescents of opportunities to develop social skills and priming them to expect mistreatment, peer rejection—particularly when unrelenting—may interfere with adolescents’ ability to successfully navigate romantic relationships.

Recognizing the relevance of the peer context for adolescents’ romantic relationship functioning, a number of studies consider peer risk factors for romantic dysfunction, especially dating aggression. For example, one recent meta-analysis pooling results from nine studies found that adolescent peer mistreatment (i.e., victimization, rejection) was significantly associated with romantic aggression (Garthe et al., 2016). However, most of the studies were cross-sectional and relied on self-reports, raising questions about longitudinal pathways from adolescents’ reputational (e.g., rejected) status to aggressive romantic behavior.

Additionally, although some studies have investigated links between peer stressors and aggression with romantic partners, less is known about how peer difficulties contribute to adolescents’ supportive romantic behaviors, or lack thereof. Understanding antecedents of adaptive romantic patterns is important inasmuch as developing the capacity to support a romantic partner is essential for intimate relationship success in adulthood (Allen, Narr, Kansky, & Szwedo, 2019). Youth repeatedly rejected across middle school may enter romantic relationships lacking practice in critical interpersonal and emotional skills, including self-regulation (McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Hilt, 2009) and problem-solving strategies (Crick & Dodge, 1994), that limit their capacity to effectively comfort and validate a romantic partner. For example, past research demonstrates that rejected youth are less likely to behave prosocially (e.g., help others; van Rijsewijk et al., 2006) and exhibit decreased social competence over time (Di Giunta et al., 2018). And yet, to our knowledge, the prospective effects of peer rejection on romantic competence—and specifically support provision—have yet to be directly investigated.

Friendship Quality as a Protective Factor

Although being disliked by peers appears to increase adolescents’ risk for problems in romantic relationships, not all rejected youth go on to exhibit partner-directed aggression or struggle with providing romantic support. A question that follows is whether the negative effects of peer rejection can be mitigated if adolescents have an opportunity to practice relationship skills in the context of close friendships. For example, there is some evidence that merely having friends during adolescence is important for romantic functioning in adulthood, such that peer rejection predicts worse romantic relationship quality for youth without friends but not youth with friends (Marion, Laursen, Zettergren, & Bergman, 2013). Beyond presence or absence of friends, the quality of these relationships also appear to matter, with some evidence indicating that perceiving trust and security within friendships can counteract the maladaptive sequalae of rejection. In the peer context, high quality friendships protect youth from escalating cycles of victimization and behavioral problems (Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 1999), and adolescents who spend more time with friends exhibit dampened sensitivity to social rejection (Masten, Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman, & Eisenberger, 2012). Romantically, adolescents who successfully form and maintain strong close friendships also experience greater romantic satisfaction into adulthood (Allen et al., 2019), whereas those with less friend support exhibit greater dating aggression perpetration (Richards & Branch, 2012). High-quality friendships are likely to provide a context for practicing supportive behaviors, such as listening and validating, that are then critical in the romantic domain (Ashley & Foshee, 2005).

High quality friendships may offer particularly important social-emotional provisions for previously rejected youth during school transitions (Aikins, Bierman, & Parker, 2005). Transitioning to a new social environment creates uncertainty about one’s social standing and fitting in and, as such, may reinforce negative expectations of others’ dislike and maltreatment. For youth who enter a new high school together with former classmates, it may also be challenging to shake a negative social reputation from middle school (Benner, Boyle, & Bakhtiari, 2017). However, as far as we know, no studies have examined whether the quality of adolescents’ friendships modifies links between negative peer experiences and romantic outcomes across middle and high school.

The Present Study

To shed light on peer-related risk and protective factors for adolescents’ romantic relationship functioning, the current study had two main aims. The first goal was to examine adolescents’ middle school experiences of peer rejection as precursors to their aggression perpetration and lack of support in a romantic relationship at eleventh grade over and above baseline aggression. We examine romantic relationships at eleventh grade because past research documents elevated rates of dating aggression among 15- to 18- year-olds compared to younger age groups (Taylor & Mumford, 2016). Recognizing that adolescents’ aggressive behavior at the start of middle school may set in motion subsequent escalations in peer rejection (Coie et al., 1990; Kornienko et al., 2019) and romantic difficulties (Ellis & Wolfe, 2015; Ha et al., 2019), and may also account for continued aggressive behaviors, we control for students’ aggressive behavior as rated by teachers during sixth grade. We hypothesized that adolescents who experienced increasing rejection across middle school would exhibit more aggression and less support in their eleventh-grade romantic relationships, even after accounting for baseline levels of aggression in middle school.

The second aim of the study was to examine whether perceived average friendship quality (i.e., across all friends) following the high school transition moderates the link between middle school peer rejection and maladaptive behaviors within a romantic relationship in high school. We hypothesized that having high-quality friendships in ninth grade buffers associations between escalating peer rejection and aggression as well as lack of support, insofar as these positive peer relationships should provide relationship skill practice. We tested our main aims by capitalizing on six waves of longitudinal, multi-reporter (i.e., student, peer, teacher) data drawn from a large sample of ethnically diverse youth in urban middle and high schools, focusing on adolescents reporting romantic relationship involvement during eleventh grade. Although not a central goal of the study, we also explore potential sex differences in links between rejection and romantic outcomes and control for differences in romantic aggression and support across adolescent sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

Method

Participants

Data for this study came from a large, longitudinal study of adolescents initially recruited from 26 urban public middle schools in California (N=5,991; 52% female). We used data collected from three consecutive cohorts of students at four time points across middle school (fall of sixth, spring of sixth, seventh, eighth grades) and two time points in high school (spring of ninth and eleventh grades). These data were collected between 2009 and 2017. As with most longitudinal studies, not all participants were retained at each wave of data collection. At the end of middle school (i.e., spring of eighth grade), 79% of the original sample was retained. Across the high school transition, a 76% participation rate was maintained from eighth to ninth grade (n=3578), and 79% from eighth to eleventh grade (n=3696). Attrition analyses indicated that relative to those without eleventh grade data, students who participated at eleventh grade were more likely to be girls [χ2(1)=22.94, p<.001] and have parents with lower levels of education [t(5522)=2.51, p=.012]. Additionally, African American students were less likely to participate at eleventh grade [χ2(5)=67.61, p<.001]. There were no differences between students with and without eleventh grade data in terms of ninth grade friendship quality [t(3409)=1.89, p= 0.059], as well as peer rejection at the beginning of middle school [t(5990)=−1.49, p= 0.137] and across middle school [t(5990)=1.33, p=.184].

Given our interest in aggression and support within romantic relationships, the analytic sample only includes participants who reported romantic involvement (past 12 months or present) at eleventh grade (n=1987; 54% female; 36% Latino/a, 21% White, 10% Asian, 11% African American, 15% Multiethnic or Biracial, and 7% from other ethnic groups). We used a broad definition of any type of self-reported romantic involvement (in a steady, committed relationship; dating someone but can see other people; “talking” to someone) currently or within the past year to capture a range of romantic experiences characteristic of high school-aged youth, rather than focusing exclusively on serious, monogamous relationships (see Furman & Collins, 2008). Rates of romantic involvement in the current sample (54%) are comparable to those documented among national samples of similarly aged youth (e.g., Carver et al., 2003). Among youth who participated at eleventh grade, chi-square and independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare the analytic sample (i.e., romantically involved) to those reporting no romantic involvement. While there were no sex differences in romantic involvement [χ2(1)=0.16, p=.686], romantically involved students had parents with lower levels of education [t(3438)=4.19, p<.035]. Ethnic differences also emerged [χ2(5)=129.43, p<.001], such that Asian students and those from other ethnic groups (i.e., not one of the four major pan-ethnic categories) were least likely to be romantically involved. In addition, compared to those not romantically involved, students who were romantically involved at eleventh grade had higher quality friendships at ninth grade [t(2735.20)=−4.60, p< 0.001] but were more rejected at the beginning of middle school [t(3694)=−3.00, p= 0.003].

Procedure

Prior to data collection, all students and families received informed consent and informational letters. Only students who turned in signed parental consent and provided written assent participated. Parent consent rates during middle school recruitment averaged 81.4%. Students completed paper questionnaires (read aloud in each classroom by trained researchers) in middle school and electronic questionnaires in high school. Instructions for completing the high school survey were audio taped and all students worked at their own pace. Students received $5 in the fall and spring of sixth grade, $10 in seventh and eighth grade, and $20 in ninth and eleventh grade. Completion of the surveys took about 45 minutes to one hour.

Measures

Time-Varying Variables.

Peer rejection was assessed at four time points in middle school (fall of sixth, and spring of sixth, seventh and eighth grades).

Peer Rejection.

Using an unlimited nomination procedure, students wrote down the names of grademates (same- or other- sex) whom they “do not like to hang out with.” For each participant, the number of nominations received was totaled, with higher numbers indicating a stronger peer rejection reputation. Typical of rejection nominations, the means were low (ranging from 0.89 – 1.18 across four waves) and standard deviations high (ranging from 1.59 – 2.19 across four waves).1 As a result, the peer rejection variable is overdispersed (i.e., standard deviation is larger than the mean) with a large positive skew. To accommodate the low modal score and long tail, we modeled growth of peer rejection using a negative binomial distribution (see analytic plan; Gazelle, Faldowski, & Peter, 2015).

Time-Invariant Variables.

Two indicators were used to assess romantic relationship functioning at eleventh grade: aggression and support. Additionally, friendship quality, demographic characteristics and teacher-rated aggression were assessed for each student.

Romantic Aggression Perpetration.

At spring of eleventh grade, participants responded to 11 items adapted from the Iowa Youth and Families Project (Conger, 2010). As shown in Table 1, students indicated the frequency with which they have perpetrated physical (e.g., “How often do/did you hit, push, grab or shove him/her?”) and psychological (e.g., “How often do/did you boss him/her around a lot?”) aggression when dating, talking or doing things with their romantic partner. Response options were given on a 7-point scale (1=always – 7=never). Items were reverse coded with higher values indicating greater romantic aggression perpetration and averaged into a composite score (α=.88; M=1.83; SD=0.86).

Table 1.

Percentage of sample reporting to each romantic perpetration and support item, broken down by sex.

| When you and your partner are (were) dating and spend (spent) time talking or doing things together, how often do (did) you… | Never (Girls/Boys) | Almost never (Girls/Boys) | Not too often (Girls/Boys) | About half of the time (Girls/Boys) | Fairly often (Girls/Boys) | Almost always (Girls/Boys) | Always (Girls/Boys) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romantic Perpetration | |||||||

| 1. Get angry at him/her | 29 / 37% | 22 / 26% | 25 / 24% | 9 / 5% | 10 / 6% | 2 / 1% | 3 / 1% |

| 2. Criticize him/her or his/her ideas | 47 / 38% | 27 / 25% | 15 / 18% | 6 / 9% | 3 / 6% | 1 / 3% | 1 / 1% |

| 3. Ignore him/her when he/she tries to talk to you | 56 / 52% | 23 / 25% | 14 / 14% | 4 / 4% | 2 / 3% | 0 / 1% | 1 / 1% |

| 4. Give him/her a lecture about how he/she should behave | 55 / 49% | 18 / 19% | 11 / 14% | 6 / 8% | 5 / 5% | 2 / 3% | 3 / 2% |

| 5. Boss him/her around a lot | 68 / 63% | 16 / 19% | 8 / 10% | 3 / 4% | 3 / 2% | 1 / 1% | 1 / 1% |

| 6. Hit, push, grab or shove him/her | 83 / 78% | 10 / 12% | 4 / 6% | 1 / 3% | 1 / 1% | 1 / 0% | 0 / 0% |

| 7. Not listen to him/her or pay attention to him/her | 74 / 64% | 15 / 19% | 6 / 9% | 2 / 4% | 1 / 2% | 1 / 1% | 1 / 1% |

| 8. Insult, swear at him/her, or call him/her bad names | 75 / 70% | 15 / 16% | 6 / 8% | 2 / 3% | 1 / 2% | 1 / 1% | 0 / 0% |

| 9. Tell him/her that you are right and he/she is wrong about things | 53 / 44% | 18 / 21% | 12 / 12% | 7 / 10% | 5 / 6% | 2 / 4% | 3 / 3% |

| 10. Threaten to hurt him/her by hitting him/her with your fist or an object | 89 / 81% | 7 / 11% | 2 / 5% | 1 / 2% | 1 / 1% | 0 / 0% | 0 / 0% |

| 11. When you are together, you spend more time on your phone than with him/her | 56 / 57% | 25 / 21% | 10 / 10% | 4 / 6% | 2 / 1% | 1 / 3% | 2 / 2% |

| Romantic Support | |||||||

| 1. Ask him/her for their opinion about an important matter | 4 / 7% | 3 / 4% | 9 / 12% | 9 / 14% | 23 / 22% | 21 / 19% | 31 / 22% |

| 2. Listen carefully to his/her point of view | 2 / 5% | 0 / 1% | 3 / 4% | 6 / 7% | 15 / 19% | 26 / 26% | 48 / 38% |

| 3. Let him/her know you really care about them | 2 / 5% | 2 / 3% | 5 / 5% | 5 / 9% | 13 / 17% | 19 / 22% | 54 / 39% |

| 4. Act supportive and understanding toward him/her | 4 / 8% | 1 / 3% | 2 / 3% | 5 / 6% | 8 / 13% | 24 / 26% | 56 / 41% |

| 5. Tell him/her you love them | 23 / 21% | 5 / 6% | 5 / 7% | 4 / 7% | 6 / 9% | 12 / 14% | 45 / 36% |

Romantic Support Provision.

Five items adapted from the Iowa Youth and Families Project (Conger, 2010) were used to assess supportive behaviors within romantic relationships (see Table 1). Students indicated how often they engage in specific behaviors with their romantic partner, such as listening, expressing affection, and acting supportive and understanding (e.g., “How often do/did you let him/her know you really care about them?”), on a 7-point scale (1=always – 7=never). Items were reverse coded with higher values reflecting greater romantic support and averaged into a composite score (α=.81; M=5.46; SD=1.37).

Friendship Quality.

At the spring of ninth grade, using an unlimited peer nomination procedure, students were asked to list the names of their good (same- or other-sex) friends in their grade at school. Friendship quality was assessed with two items capturing emotional security and support (i.e., “This friend helps me feel better when I’m upset;” “This friend sticks up for me/has my back), adapted from widely used measures in childhood and adolescence (see Furman, 1996). Responses to the two items (r=.64) on the 3-point scale (1=no/hardly ever – 3=yes/almost all the time) were averaged for each friend and then across all nominated friends, with higher values indicating higher friendship quality (M=2.69, SD=0.35).

Covariates.

Prior research documents differences in romantic outcomes (e.g., aggression) as a function of adolescent sex (Wincentak, Connolly, & Card, 2016), ethnicity (Eaton et al., 2012), and socioeconomic status (Foshee et al., 2008). Therefore, in the main analyses we controlled for self-reported sex (1=girl, 0=boy), ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Ethnicity was represented by five dummy variables (African American, Asian, White, Multiethnic, Other), using Latino students (the largest ethnic group in the sample) as the reference group. Parent education (1=elementary/junior high school to 6=graduate degree) was used as a proxy for student socioeconomic status. Additionally, in light of documented associations between peer rejection and aggressive/antisocial behavior (Coie et al., 1990; Ha et al., 2019; Kornienko et al., 2019), we accounted for teacher-rated aggression at the end of the first year in middle school (spring of sixth grade), when teachers have had opportunity to get to know students’ behavior well. Teachers who had daily classroom contact with students rated each student’s frequency of aggressive behavior (i.e., starts fights, mean to others) using two items adapted from the Interpersonal Competence Scale (ICS-T; Cairns, Leung, Gest, & Cairns, 1995), which were rated on a 7-point scale (1=always – 7=never), reverse coded and averaged into a composite score (r=.76; M=1.78; SD=1.11).

Analytic Plan

Latent growth curve models (LGCM) were conducted in Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2018) using a structural equation modeling framework. LGCM is an ideal approach to account for individual variations in peer rejection and its effect on romantic outcomes given that individual growth is estimated separately for each adolescent. The LGCM approach can be applied to non-normal distributions, including count variables (Asparouhov & Muthen, 2014). Because peer rejection was a significantly overdispersed count variable, we used a negative binomial function and a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR). Negative binomial models are designed to handle dependent variables with distributions incorporating many zero values and large positive skews (Gazelle et al., 2015).2 Missing data were handled with full information maximum likelihood estimation (Enders, 2010).

To test whether dating behaviors can be predicted by earlier middle school peer rejection experiences, as an initial step we use an unconditional negative binomial LGCM to estimate latent intercept (i.e., peer rejection at the beginning of middle school) and slope (i.e., rate of change in peer rejection across middle school) parameters. Time points were fixed incrementally to reflect the data assessment schedule (i.e., fall of sixth grade=0, spring of sixth grade=.5, spring of seventh grade=1.5, spring of eighth grade=2.5). Next, a series of conditional LGCMs tested the associations between peer rejection and dating behaviors (i.e., romantic aggression perpetration and support provision). First, we examined the main effects of middle school peer rejection intercept and slope, while controlling for sex, ethnicity, SES, teacher-rated aggression and friendship quality. Second, to test whether the effect of peer rejection varied as a function of the quality of students’ ninth-grade friendships, interaction terms between the latent peer rejection constructs and friendship quality were created using the XWITH command in Mplus and tested one at a time with all lower-order terms in the models. Statistically significant interactions were decomposed to compare the effects of peer rejection for students with low (−1 SD), average, and high (+1 SD) quality friendships. For conditional LGCMs, multiple group analyses were also used to examine sex differences among the observed associations.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Item-level frequencies of eleventh-grade aggressive and supportive romantic behaviors are reported by sex in Table 1. Frequencies of aggression perpetration toward romantic partners ranged from 15% - 67% and frequencies of support ranged from 78% - 97%. The two outcomes were uncorrelated (r=−.02), suggesting that within romantic relationships aggression and support are independent constructs, rather than simply inverse of one another.

Unconditional LGCM

Results from the unconditional LGCM indicated a non-significant slope of peer rejection (b=−.024, p=.423) and significant variance around the slope [var(b)=.042, p=.006]. The non-significant slope indicates that, in the sample as a whole, there was no significant change in peer rejection across middle school. However, the significant variance indicates that there are individual differences in the patterns of longitudinal change in peer rejection between adolescents. That is, although the average peer rejection trajectory for the sample appeared relatively stable, there were significant differences in patterns of change in peer rejection across individuals from sixth to eighth grade.

Peer Rejection Trajectories Predicting Romantic Functioning

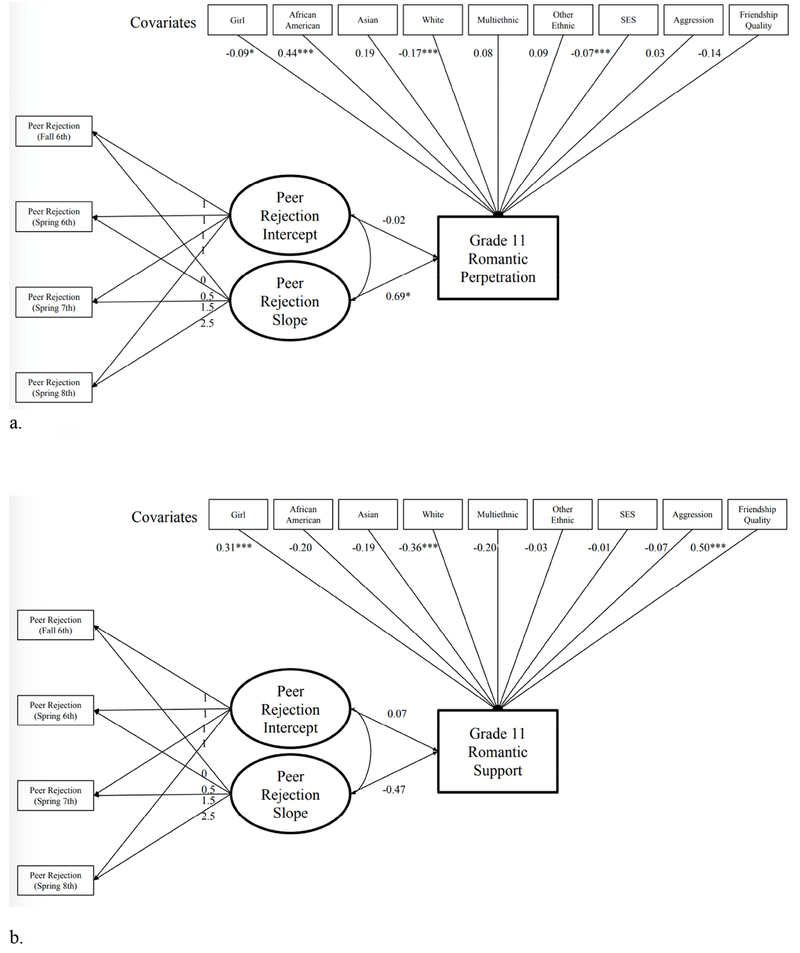

To explore how these individual differences in peer rejection are related to romantic aggression and support at eleventh grade, conditional LGCMs including between-person effects were estimated. First, we examined how the intercept and slope of peer rejection predicted romantic aggression and support, while controlling for sex, ethnicity, SES, teacher-rated aggression and friendship quality (see Figures 1a and 1b). Girls reported lower levels of aggression perpetration and higher levels of support in their romantic relationships, relative to boys (see also Table 1). Additionally, African American students reported higher levels of aggression perpetration compared to Latinos, while White students reported lower levels of perpetration and support than Latinos. Lower socioeconomic status was associated with greater aggression perpetration. Finally, students with lower quality ninth-grade friendships reported engaging in fewer supportive romantic behaviors.

Figure 1.

Conditional LGCM of middle school peer rejection predicting eleventh grade romantic perpetration and support. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

a. Unstandardized effect estimates of peer rejection and covariates predicting romantic perpetration.

b. Unstandardized effect estimates of peer rejection and covariates predicting romantic support.

Peer rejection at the beginning of middle school (i.e., intercept) was unrelated to both aggression perpetration (b=−0.02, p=.477) and support (b=0.07, p=.088). However, as expected, change in peer rejection across middle school (i.e., slope) was positively related to romantic aggression. Students who experienced steeper increases in peer rejection from sixth to eighth grade reported higher levels of aggression perpetration toward their romantic partner at eleventh grade (b=0.69, p=.050). In contrast, changes in peer rejection were unrelated to romantic support (b=−0.47, p=.365).

Multiple group analysis was conducted to examine potential sex differences in the association between the peer rejection slope and romantic aggression perpetration. A Wald chi-square test revealed that the effect for boys and the effect for girls were not significantly different from each other (χ2(1)=0.94, p=.331), although inspection of sex-specific parameters for the association suggested that the effect was driven by boys (b=1.34, p=.021) more so than girls (b=0.61, p=217).

Friendship Quality as a Moderator

To examine whether the associations between middle school peer rejection and dating behaviors vary as a function of the quality of students’ friendships, we tested two latent interactions: Peer Rejection Intercept X Friendship Quality and Peer Rejection Slope X Friendship Quality (see Table 2). When predicting romantic aggression, neither the effect of baseline rejection (b=0.07, p=.339), nor change in rejection across middle school (b=−0.60, p=.720), varied as a function of friendship quality.

Table 2.

Interactive effects of middle school peer rejection and ninth grade friendship quality on eleventh grade romantic support.

| Predictors | b | (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Girl | 0.302** | (.09) |

| African American | −0.116 | (.12) |

| Asian | −0.212 | (.14) |

| White | −0.362** | (.11) |

| Multiethnic | −0.181 | (.15) |

| Other Ethnic | 0.036 | (.11) |

| SES | −0.007 | (.03) |

| Teacher-Rated Aggression | −0.054 | (.04) |

| Friendship Quality | 0.608*** | (.16) |

| Peer Rejection Intercept | 0.064 | (.05) |

| Peer Rejection Slope | −0.402 | (.42) |

| Peer Rejection Slope X Friendship Quality | 2.217* | (1.08) |

Note. Sex reference group=Boy; Ethnicity reference group=Latino. The peer rejection intercept X friendship quality interaction was non-significant and therefore removed from the model.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05

When predicting romantic support, one significant interaction emerged. Although the peer rejection intercept did not interact significantly with friendship quality (b=−0.01, p=.924), there was a significant interaction between changes in peer rejection across middle school and the ninth-grade friendship quality (b=2.22, p=.041). Among students with low friendship quality following the transition to high school, increases in peer rejection across middle school were related to lower levels of romantic support at eleventh grade (b=−1.16, p=.037). However, for students with average (b=−0.40, p=.340) and high (b=0.35, p=.533) quality friendships, increases in peer rejection across middle school were not related to their level of supportive behavior in romantic relationships at eleventh grade. Multiple group analysis revealed no significant sex differences in the moderating role of friendship quality, χ2(1)=0.79, p=.373. Thus, good quality friendships during the transition to high school moderated the association between increased peer rejection in middle school and supportive (but not aggressive) behaviors within subsequent romantic relationships.

Discussion

Learning how to form successful romantic relationships is a central task of adolescence. Capitalizing on six years of longitudinal data and multiple reporting sources, the present study demonstrates the ways in which earlier social experiences predict behaviors within romantic relationships at eleventh grade, implicating escalating peer rejection in middle school as a precursor of problematic romantic functioning in high school. Students who became increasingly disliked by their peers across middle school were more likely to then behave aggressively in their high school romantic relationships, regardless of friendship quality. However, high quality friendships at the high school transition, a time of uncertainty, protected rejected youth from engaging in unsupportive behaviors within romantic relationships. Our findings offer insights about continuities across relationship contexts (peers and romantic partners) and the power of close friendships to disrupt negative developmental pathways.

Longitudinal analyses demonstrated that, consistent with our hypotheses, adolescents who became increasingly disliked by peers across middle school reported greater aggression perpetration in their eleventh-grade romantic relationships. Although past research has begun to explore continuities between adolescents’ negative peer and romantic experiences, such as dating aggression, the current study offered a novel contribution by also considering when and how peer stressors contribute to adolescents’ supportiveness in romantic contexts. In addition to documenting that adolescents’ negative peer experiences heighten their aggressive romantic behaviors, we found evidence that adolescents’ escalating rejection experiences limited their supportive romantic behaviors, at least in the absence of high-quality friendships. When peer-rejected youth did not feel supported by their friends during the first year of high school, they were less likely to display supportive behaviors within a romantic relationship. But, when adolescents perceived their ninth-grade friends to be trustworthy and caring, increases in their own middle school rejection did not predict lower levels of romantic support provision.

As suggested by research examining the role of friendships at the transition to middle school (e.g., Aikins et al., 2005), the high school transition may offer a “fresh start” for previously rejected youth. High-quality friendships in high school may then compensate for rejection from the peer group during middle school or help socially vulnerable youth more effectively navigate a new, and oftentimes challenging, school environment. From this view, good friends may serve a “social skills enhancing” function for rejected youth, and interpersonal competencies (e.g., warmth, support) acquired in the friendship context are later applied in romantic contexts (Collins & Sroufe, 1999). A question that follows is when and why some peer-rejected youth are able to develop high-quality friendships in high school. One alternative explanation for our findings is that adolescents who are able to make close, strong friendships in high school despite a history of peer rejection represent a particularly resilient or skilled group who will also exhibit a greater capacity for sympathy and support in their romantic relationships. Although we cannot disentangle influence versus selection effects here, it will be a promising avenue for future research linking peer and romantic competencies.

Inconsistent with our hypotheses, high quality friendships did not buffer associations between increasing peer rejection and romantic aggression perpetration. A closer look at the characteristics of adolescents’ ninth grade friends could potentially shed light on this finding. Although the large size of our sample and wide distribution of students across many high schools prohibited us from capturing detailed information about friendship networks, past research suggests that peer rejected youth often affiliate with antisocial peers who themselves engage in romantic aggression perpetration (Arriaga & Foshee, 2004; Foshee, McNaughton Reyes, & Ennett, 2010). Some of the peer rejected youth in our study may have developed supportive friendships with deviant peers; in turn, despite socially and emotionally benefiting from a close, caring friendship, they may also learn to accept and even model coercive behaviors in their own romantic relationships. Notably, romantic aggression and support were not correlated with one another, suggesting that peer rejection maps onto two distinct forms of relationship dysfunction in unique ways.

Although an investigation of underlying mechanisms was beyond the scope of our study, here we briefly outline several possible explanations for the current results that should be directly tested in future research. From a social-information processing perspective (Crick & Dodge, 1994), targets of peer mistreatment develop maladaptive expectations for future social encounters (e.g., hypervigilance to threat cues), which make aggressive responses more accessible and desirable. Adolescents entering romantic relationships after years of peer mistreatment may react quickly and maladaptively (i.e., aggressively; Dodge & Pettit, 2003) to any possible threat of rejection (e.g., romantic spat) or exclusion (Will, Crone, van Lier, & Güroğlu, 2016). It is also possible that selection effects are at play, wherein rejected youth gravitate towards partners that may themselves be reactive or aggressive, although prior research suggests greater similarity among adolescent partners on “visible” features (e.g., attractiveness) compared to reputational characteristics (e.g., aggression or victimization; Simon, Aikins, & Prinstein, 2008). Further research that investigates the dynamic interplay between patterns of aggression and rejection across relationship contexts (e.g., Ha et al., 2019; Ha et al., 2016) will be important in disentangling these complex patterns.

Descriptively, the current study also sheds light on dating aggression prevalence rates among an ethnically diverse school sample of romantically involved youth. Over half of the sample reported having criticized and gotten angry with their romantic partner, while about one fifth said they have perpetrated physical aggression. The relatively high overall perpetration rate mirrors rates reported in other research with similar high school samples (e.g., O’Leary, Smith Slep, Avery-Leaf, & Cascardi, 2008). Although the average rates of romantic aggression perpetration were quite high, it is encouraging to see even higher rates of romantic support reported among romantically involved adolescents. Almost all youth reported engaging in some (often multiple) forms of support towards their romantic partners, such as listening carefully to a partner’s point of view and showing a partner they care. Examination of demographic differences in romantic outcomes highlighted higher rates of aggression perpetration among boys than girls, but higher rates of support provision among girls than boys, mirroring past research on gendered interpersonal support processes (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Prevalence rates for aggression also varied across ethnicity and SES, consistent with prior research (e.g., Eaton et al., 2012; Foshee et al., 2008): Latino and African American youth and students from lower SES families reporting higher rates of romantic aggression perpetration. Together these findings highlight the importance of offering widely accessible school-based health programs for youth, not only to provide basic “sex ed” but also to help develop adolescents’ positive relationship skills (Adler-Baeder, Kerpelman, Schramm, Higginbotham, & Paulk, 2007).

The current study had several limitations. First, although we incorporated multiple reporting sources (self, peer, teacher) across measures to minimize the possibility of shared method variance, adolescents’ self-reports of dating aggression perpetration may yield underestimates of these behaviors. Studies that recruit and collect data from adolescent couples would circumvent issues of self-report biases by evaluating perpetration from the partner’s (i.e., target’s) point of view (e.g., Rogers, Ha, Updegraff, & Iida, 2018). Also relating to measurement issues, friendship quality was based off of only two self-report items and averaged across all nominated friends to capture overall friendship quality (i.e., students were not asked to identify a “best friend”). Despite the measure capturing two essential components of adolescents’ friendships (relational support and security), it would be important to replicate the current results using a multidimensional scale that taps into other important friendship features, such as intimate disclosure, which may meaningfully contribute to the way youth navigate their romantic experiences. The current findings may also be better understood if more information was available about the social experiences of friends. For example, if a rejected adolescent primarily affiliates with other rejected youth, this may undermine opportunities for positive “relationship practice”. Additionally, because we did not distinguish between “best friendships” and other friendships nor could we track the identity of participants’ friends across our many (100+) participating high schools, we do not capture mutuality of friendships or the potential variability in quality across adolescents’ different friendships. Finally, given that we did not specifically consider the role of sexual orientation in our analyses, it will be critical for future research to investigate whether the current findings generalize across heterosexual and sexual minority youth and to better understand shared (or unique) predictors of romantic outcomes (e.g., aggression, support) within same-sex youth couples.

Nevertheless, this study contributes to our understanding of developmental connections between peer and romantic domains. By focusing on both aggressive and supportive relationship outcomes, we highlight that peer mistreatment not only heightens adolescents’ risk for displaying problematic partner-directed behaviors, but also reduces the likelihood of youth displaying constructive partner-directed behaviors if they lack close, caring friends across the high school transition. Additionally, the findings underscore the value of considering peer experiences as they unfold over time—peer rejection was uniquely consequential for romantic functioning when adolescents’ negative reputation grew and solidified across the middle school years. When thinking about the development and implementation of school-based sexual and relationship education programs, it will be critical to recognize that every adolescent brings a unique social history into their romantic relationships. Starting these programs early with an emphasis on how to foster caring and supportive friendships could have downstream benefits for adolescents’ romantic functioning.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr. Sandra Graham and the members of the UCLA Diversity Project for their contributions to collection of the data, as well as all school personnel and participants for their cooperation. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Grant 1R01HD059882-01A2) and the National Science Foundatrion (No. 0921306). The first author (HS) was also supported by a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (NSF SPRF 1714304).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Across middle school, the percent of students receiving zero rejection nominations at any given wave ranged from 50 to 56%.

Because count models do not yield traditional fit indices (e.g., root mean square error of approximation, RMSEA), no model fit indices are reported.

References

- Adler-Baeder F, Kerpelman JL, Schramm DG, Higginbotham B, & Paulk A (2007). The impact of relationship education on adolescents of diverse backgrounds. Family Relations, 56, 291–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00460.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aikins JW, Bierman KL, & Parker JG (2005). Navigating the transition to junior high school: The influence of pre-transition friendship and self-system characteristics. Social Development, 14, 42–60. doi: 10.im/j.1467-9507.2005.00290.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Narr RK, Kansky J, & Szwedo DE (2019). Adolescent peer relationship qualities as predictors of long-term romantic life satisfaction. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, & Foshee VA (2004). Adolescent dating violence: do adolescents follow in their friends’, or their parents’, footsteps? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 162–184. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley OS, & Foshee VA (2005). Adolescent help-seeking for dating violence: prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and sources of help. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36, 25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, & Leary MR (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Boyle AE, & Bakhtiari F (2017). Understanding students’ transition to high school: Demographic variation and the role of supportive relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 2129–2142. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0716-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, & Montminy HP (1993). Developmental issues in social-skills assessment and intervention with children and adolescents. Behavior Modification, 17, 229–254. doi: 10.1177/01454455930173002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Jones SE, Kann L, & McManus T (2003). Variation in school health policies and programs by demographic characteristics of US schools. Journal of School Health, 73, 143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B (1990). Peer groups In Feldman S & Elliott G (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 171–196). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R, Leung M, Gest S, & Cairns B (1995). A brief method for assessing social development: Structure, reliability, stability, and developmental validity of the interpersonal competence scale. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 33, 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, & Udry JR (2003). National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships In Florsheim P (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 23–56). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, & Kupersmidt JB (1990). Peer group behavior and social status In Asher SR & Coie JD (Eds.), Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. Peer rejection in childhood (pp. 17–59). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & Sroufe LA (1999). Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction In Furman W, Brown BB, & Feiring C (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 125–147). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & van Dulmen MHM (2006). “The course of true love(s)… ”: Origins and pathways in the development of romantic relationships In Crouter AC & Booth A (Eds.), The Penn State University family issues symposia series. Romance and sex in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Risks and opportunities (pp. 63–86). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Furman W, & Konarski R (2000). The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger R (2010). Iowa Youth and Families Project, 1989-2000. doi: 10.7919/DVN/PTVNNC [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1994). A review and reformulation of social-information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giunta L, Pastorelli C, Thartori E, Bombi AS, Baumgartner E, Fabes RA Enders CK (2018). Trajectories of Italian children’s peer rejection: Associations with aggression, prosocial behavior, physical attractiveness, and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 1021–1035. doi: 10.1007/s10802-017-0373-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, & Price JM (2003). Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development, 74, 374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Pettit GS (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Bonica C, & Rincón C (1999). Rejection sensitivity and adolescent romantic relationships In Furman W, Brown BB, & Feiring C (Eds.), Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 148–174). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint K, Hawkins J, et al. (2012). Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 61, 1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, & Wolfe DA (2015). Bullying predicts reported dating violence and observed qualities in adolescent dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30, 3043–3064. doi: 10.1177/0886260514554428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, & Rothman E (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics, 131, 71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Reyes HL, Ennett ST, Suchindran C, Bauman KE, et al. (2008). What accounts for demographic differences in trajectories of adolescent dating violence? An examination of intrapersonal and contextual mediators. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42, 596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, & Ennett ST (2010). Examination of sex and race differences in longitudinal predictors of the initiation of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19, 492–516. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.495032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W (1996). The measurement of friendship perceptions: Conceptual and methodological issues In Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, & Hartup WW (Eds.), The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence (pp. 41–65). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W (1999). The role of peer relationships in adolescent romantic relationships In Collins WA & Laursen B (Eds.), Minnesota Symposium on Child Development: Vol 29. Relationships as developmental contexts (pp. 133–154). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W (2002). The emerging field of adolescent romantic relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 177–180. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W & Collins WA (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships and experiences In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. (pp.341–360). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garthe RC, Sullivan TN, & McDaniel MA (2016). A meta-analytic review of peer risk factors and adolescent dating violence. Psychology of Violence, 7, 45–57. doi: 10.1037/vio0000040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Faldowski RA, & Peter D (2015). Using peer sociometrics and behavioral nominations with young children In Saracho ON (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in early childhood education: Review of research methodologies (Vol. 1, pp. 27–70). Charlotte, NC: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Otten R, McGill S, & Dishion TJ (2019). The family and peer origins of coercion within adult romantic relationships: A longitudinal multimethod study across relationships contexts. Developmental Psychology, 55, 207–215. doi: 10.1037/dev0000630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Kim H, Christopher C, Caruthers A, & Dishion TJ (2016). Predicting sexual coercion in early adulthood: The transaction among maltreatment, gang affiliation, and adolescent socialization of coercive relationship norms. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 707–720. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Farhat T, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Barbieri B, & Iannotti RJ (2013). Dating violence perpetration and victimization among U.S. adolescents: prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Boivin M, Vitaro F, & Bukowski WM (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35 (1), 94–101. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J (2013). Peer rejection among children and adolescents: Adolescents, reactions, and maladaptive pathways In DeWall CN (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of social exclusion (pp. 101–110). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kornienko O, Ha T, & Dishion TJ (2019). Dynamic pathways between rejection and antisocial behavior in peer networks: Update and test of confluence model. Development and Psychopathology, 1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW (1999). Peer relationships and social competence during early and middle childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JR, & Collins WA (2005). Parent and peer predictors of physical aggression and conflict management in romantic relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 252–262. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion D, Laursen B, Zettergren P, & Bergman LR (2013). Predicting life satisfaction during middle adulthood from peer relationships during mid-adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1299–1307. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9969-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, & Eisenberger NI (2012). Time spent with friends in adolescence relates to less neural sensitivity to later peer rejection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7, 106–114. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hilt LM (2009). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2018). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bukowski WM, & Pattee L (1993). Children’s peer relations: a meta-analytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 99–128. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Smith Slep AM, Avery-Leaf S, & Cascardi M (2008). Gender differences in dating aggression among multiethnic high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42, 473–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JP, Parra GR, & Bennett SA (2010). Predicting violence in romantic relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood: A critical review of the mechanisms by which familial and peer influences operate. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Lansford JE, Malone PS, Dodge KA, & Bates JE (2010). Domain specificity in relationship history, social-information processing, and violent behavior in early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 190–200. doi: 10.1037/a0017991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, & Cillessen AHN (2003). Forms and functions of adolescent peer aggression associated with high levels of peer status. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 310–342. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards TN, & Branch KA (2012). The relationship between social support and adolescent dating violence: a comparison across genders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 1540–1561. doi: 10.1177/0886260511425796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AA, Ha T, Updegraff KA, & Iida M (2018). Adolescents’ daily romantic experiences and negative mood: a dyadic, intensive longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 1517–1530. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0797-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Rudolph KD (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon VA, Aikins JW, & Prinstein MJ (2008). Romantic partner selection and socialization during early adolescence. Child Development, 79, 1676–1692. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BG, & Mumford EA (2016). A national descriptive portrait of adolescent relationship abuse: Results from the National Survey on Teen Relationships and Intimate Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31, 963–988. doi: 10.1177/0886260514564070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Bongardt D, Yu R, Deković M, & Meeus WHJ (2015). Romantic relationships and sexuality in adolescence and young adulthood: The role of parents, peers, and partners. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 497–515. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2015.1068689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijseijk L, Dijkstra JK, Pattiselanno K, Steglich C, & Veenstra R (2016). Who helps whom? Investigating the development of adolescent prosocial relationships. Developmental Psychology, 52, 894–908. doi: 10.1037/dev0000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbourd R, Anderson T, Cashin A, & McIntyre J (2017). The talk: How adults can promote young people’s healthy relationships and prevent misogyny and sexual harassment Making Caring Common Project: Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://mcc.gse.harvard.edu/thetalk. [Google Scholar]

- Will GJ, Crone EA, van Lier PAC, & Güroğlu B (2016). Neural correlates of retaliatory and prosocial reactions to social exclusion: Associations with chronic peer rejection. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincentak K, Connolly J, & Card N (2016). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychology of Violence, 7, 224–241. doi: 10.1037/a0040194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2016). Peer rejection, victimization, and relational self-system processes in adolescence: Toward a transactional model of stress, coping, and developing sensitivities. Child Development Perspectives. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Nesdale D, Webb HJ, Khatibi M, & Downey G (2016). A longitudinal rejection sensitivity model of depression and aggression: Unique roles of anxiety, anger, blame, withdrawal, and retribution. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 1291–1307. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0127-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]