Abstract

Global change and biotic stress, such as tropospheric contamination and virus infection, can individually modify the quality of host plants, thereby altering the palatability of the plant for herbivorous insects. The bottom-up effects of elevated O3 and tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) infection on tomato plants and the associated performance of Bemisia tabaci Mediterranean (MED) were determined in open-top chambers. Elevated O3 decreased eight amino acid levels and increased the salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) content and the gene expression of pathogenesis-related protein (PR1) and proteinase inhibitor (PI1) in both wild-type (CM) and JA defense-deficient tomato genotype (spr2). TYLCV infection and the combination of elevated O3 and TYLCV infection increased eight amino acids levels, SA content and PR1 expression, and decreased JA content and PI1 expression in both tomato genotypes. In uninfected tomato, elevated O3 increased developmental time and decreased fecundity by 6.1 and 18.8% in the CM, respectively, and by 6.8 and 18.9% in the spr2, respectively. In TYLCV-infected tomato, elevated O3 decreased developmental time and increased fecundity by 4.6 and 14.2%, respectively, in the CM and by 4.3 and 16.8%, respectively, in the spr2. These results showed that the interactive effects of elevated O3 and TYLCV infection partially increased the amino acid content and weakened the JA-dependent defense, resulting in increased population fitness of MED on tomato plants. This study suggests that whiteflies would be more successful at TYLCV-infected plants than at uninfected plants in elevated O3 levels.

Keywords: Bemisia tabaci Mediterranean, elevated O3, tomato yellow leaf curl virus, jasmonic acid, tomato

The growth-limiting resources such as physical and chemical qualities of plant tissues could be reallocated by the changes of environmental stress (Agrell et al. 2005, Cui et al. 2012). Generally, the phloem-feeding insects (e.g., whitefly) could be affected by plant physiology associated with nutrition and resistance (Zhang et al. 2013). Widespread studies have shown that phytohormones such as jasmonic acid (JA) play an important role in the external stress response and in the maintenance of the balance between defense and growth, which may mediate the cascading effects of biotic and abiotic stress on herbivorous insects and their natural enemies along the food chain (Zhang et al. 2012, Cui et al. 2016). Systemic JA signaling can effectively transmit wounding-associated signals from the site of local attack to potentially vulnerable systemic regions during priming defense (Conrath et al. 2006, Thines et al. 2007). Priming defense is a physiological process in which plants prepare to respond more quickly or more actively to climate change and biotic stress (Frost et al. 2008). This process extensively affects and modifies insect and plant interactions in response to environmental stress, pathogenic infection, and insect occurrence (Sun et al. 2013, 2017).

The global atmospheric concentration of ozone (O3) has risen by 0.5–2.5% per year from 10 nl/liter in the 1900s to 40 nl/liter today (Blande et al. 2010, Yuan et al. 2016), and is predicted to reach 75 nl/liter by 2050 (Ainsworth et al. 2012, IPCC 2014). O3 is by far the most phytotoxic air pollutant and is a strong oxidant (Overmyer et al. 2009). After entering the plant stomata, O3 is broken down in the apoplast to form reactive oxygen species (ROS), which in turn trigger an active oxidative burst within the plant, affecting substances such as carbohydrates and proteins and altering lipid oxidation (Yang et al. 2017, Zhang et al. 2017, Cui et al. 2018). O3 reacts primarily with the plasma membrane, causing alterations in lipoxygenase activities and increasing the production of linoleic acid, a precursor of JA biosynthesis (Rao et al. 2000, Wasternack and Hause 2013). Elevated O3 levels trigger JA biosynthesis, resulting in alteration of insect occurrence via priming defense (Bilgin et al. 2008, Guo et al. 2017). However, few studies have examined the effects of O3-induced peroxidation in defense priming, especially on phloem-sucking insects.

In addition to abiotic stress, viral infection can shape whitefly–virus–plant associations. Begomoviruses are the most harmful group of plant viruses in tropical and warm temperate regions of the world, and outbreaks of whiteflies in many regions are often accompanied by tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), which is one of the most destructive monopartite begomoviruses and has spread worldwide (Bilgin et al. 2008, Guo et al. 2017). TYLCV reportedly increases the fitness of the vector Mediterranean (MED) whitefly via suppression of the JA defense pathway (Sun et al. 2017). Furthermore, the pathogenicity factor ßC1 promotes the repressive role of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 (AS1) in the regulation of JA signaling, which benefits vector whitefly performance and geminivirus spread (Yang et al. 2008). Viral infection reduced the expression of the basic helix–loop–helix zipper transcription factor MYC2 (downstream gene of JA pathway) via priming defense and suppressed the synthesis and release of terpenoid such as β-myrcene, which is favorable for whitefly preference and feeding (Dombrecht et al. 2007, Li et al. 2014). However, the interactive effects of viral infection and elevated O3 levels on plant-whitefly interactions are largely unknown.

The whitefly, Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), is an invasive agricultural pest worldwide, damaging plants by directly ingesting phloem sap and more seriously by transmitting plant viruses (Stansley and Naranjo 2010). Bemisia tabaci MED has recently invaded and spread in China and has caused enormous agricultural loss due to feeding and as a vector of TYLCV (Chu et al. 2010, Rao et al. 2011). Previous studies have shown that TYLCV infection tends to repress the JA-related resistance of tomato plants, whereas O3 could activate the JA signaling pathway via the lipoxygenase biosynthetic pathway (Wasternack and Hause 2013, Sun et al. 2017). However, the mechanism by which the interaction of viral infection and elevated O3 levels affect JA signaling and the subsequent influence of B. tabaci MED remains unclear. Moreover, once the JA pathway is impaired, it is unclear whether the effect of priming defense can be transmitted and what the response of the MED whitefly is. We proposed a hypothesis that the antagonistic effect of elevated O3 on virus infection will increase the fitness of whitefly MED via induced nutritional substance and defense pathways of CM and spr2 tomato plants. Our specific aims were to determine the effects of elevated O3 levels and TYLCV infection in combination on 1) the nitrogenous nutritional quality of plant in terms of amino acid content of plant leaves, induced defense pathways and related gene expression in two tomato genotypes that differed with respect to the JA-dependent defense pathway and on 2) the performance of B. tabaci MED fed on the two tomato genotypes.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Procedures

A split–split plot design was used with O3 and block (a pair of ambient and elevated open-top chambers [OTCs]) as the main effects, TYLCV as the subplot effect, and tomato genotypes as the sub-subplot effect. The model was as follows:

where O is the O3 treatment (i = 2), B is the block (j = 3), V is the TYLCV treatment (k = 2), and T is the tomato genotype (l = 2). Xijklm represents the error because of the small-scale differences between samples and variability within blocks (ANOVA, SAS Institute). Totally, there were eight treatments in the present experiment. The whitefly MED developmental time, fecundity, and tomato physiology (amino acids, jasmonic acid [JA], salicylic acid [SA], and their related gene expressions) were determined to examine the differences among treatments.

Open-Top Chambers

The experiment was conducted in six hexagonal OTCs, each 2.2 m in height and 2 m in diameter, at the Observation Station for Global Change Biology, Institute of Zoology of the Chinese Academy of Science, in Xiaotangshan County, Beijing, China (40°11′N, 116°24′E). In the elevated O3 treatment, O3 was generated from ambient air by an O3 generator (3S-A15, Tonglin Technology, Beijing, China). A detailed description of the O3 generation system and transfer process was provided by Cui et al. (2014). The actual daily O3 concentration (within 10 h from 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.) averaged 37.3 nl/liter in the ambient chambers and 72.2 nl/liter in the elevated chambers. The ozone concentration range was 35–39 nl/liter in the ambient chambers and 69–75 nl/liter in the elevated chambers. O3 concentrations were monitored within OTCs (AQL-200, Aeroqual) hourly. The O3 treatment was applied for 4 wk. We measured the air temperature and humidity throughout the experiment in the ambient chambers (27.8 ± 1.8°C, 59.8 ± 11.3% RH) and in the elevated chambers (28.3 ± 2.5°C, 59.3 ± 13.1% RH).

Whitefly and Host Plants

The B. tabaci MED population was reared on cotton in climate-controlled rooms (27 ± 1°C, 70 ± 10% RH, and 14:10 [L:D] light cycle). The biotype was determined by assessing amplified fragment-length polymorphism markers (Zhang et al. 2005).

Seeds of the following two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) cultivars were used: Lycopersicon esculentum cv. Castlemart (CM) and suppressor of prosystemin-mediated responses 2 (spr2; jasmonate-deficient mutant tomato plant). The spr2 mutant tomato decreases chloroplast w3 fatty acid desaturase content, which impairs the synthesis of JA (Li et al. 2003). Two-week-old seedlings were transferred to plastic pots (14 cm diameter, 12 cm height) containing sterilized loamy soil.

TYLCV Cloning and Inoculation

We infected 64 tomato plants with TYLCV via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated inoculation at the second–third true-leaf stage. The infectious clone (pBINPLUS-SH2-1.4A) of TYLCV-Israel [CN: SH2] was constructed into the A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 as described previously (Zhou et al. 2009). The TYLCV clone was cultured in LB culture medium with kanamycin (50 µg/ml) and rifampicin (50 µg/ml) at 28°C (250 rpm) for 24 h (OD600 = 1.5), after which, 0.5 ml of the culture was injected three times into the phloem (approximately 1 mm in depth) of the tomato stem for inoculation (Huang et al. 2012, Su et al. 2016). Viral infection of the test plants was confirmed by characteristic leaf curl symptoms and by PCR as previously described (Ghanim et al. 2007). Inoculated plants were subjected to further experimental treatments at the sixth–seventh true-leaf stage (approximately 30 d after agroinoculation of the virus) and moved to ventilated cages (1.0 m long, 1.0 m wide, 1.8 m high, 80 mesh) in the OTCs. Two ventilated cages were placed in each of the six OTCs. Infected plants in each cage were inoculated with TYLCV, whereas control plants were mock-inoculated using LB culture medium. The TYLCV infection treatment was applied for 58 d.

Amino Acid Analysis

Free amino acids were extracted and quantified from the harvested leaves according to Guo et al. (2016). The amino acids in each sample were analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with precolumn derivatization using o-phthaldialdehyde and 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl. Amino acids were quantified using the AA-S-17 (Agilent) reference amino acid mixture supplemented with asparagine, glutamine, and tryptophan (Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). Standard solutions were prepared from a stock solution by dilution with 0.1 M HCl. Analyses were performed using an Agilent 1100 HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA); a reverse-phase Agilent Zorbax Eclipse AAA C18 column (5 µm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm) and fluorescence detector were used for chromatographic separation. Amino acid concentrations were quantified by comparison of sample peak areas to standard curves of 20 reference amino acids.

SA and JA Measurements and Quantitative PCR Analysis

Approximately 0.2-g fresh leaf tissue was extracted for quantification of SA and JA levels as described previously (Guo et al. 2016).

Following procedures described by Cui et al. (2017), a sample of fresh leaves from each plant was removed and stored at −78°C for real-time PCR. Each treatment combination was repeated for three biological replicates, and each biological replicate contained three technical replicates. Total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's protocol and was quantified using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific). After RNA extraction, 1 µg of RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa) with gDNA Eraser according to the manufacturer's protocol. The quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to analyze differences in expression. Gene-specific primers for the two genes (pathogenesis-related protein [PR1] and proteinase inhibitor gene [PI1]) were designed and used for PCR. The 25-µl reactions contained 10.5 µl of ddH2O, 12.5 µl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Tiangen, Beijing, China), 1 µl of cDNA template, and 0.5 µl of each primer. Specific primers for the target genes were designed based on the tomato EST sequences using PRIMER5 software (Supp Table 1 [online only]). The qPCR program included an initial denaturation step for 15 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 15 s at 95°C, annealing for 30 s at 60°C, and extension for 32 s at 72°C. For melting curve analysis, an automatic dissociation step cycle was added. Reactions were performed in an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with data collection at stage 2, step 3 in each cycle of the PCR. The melting curves were used to determine the specificity of the PCR products. A standard curve was derived from serial dilutions to quantify the copy numbers of target mRNAs. The relative level of the target gene was standardized by comparing the copy numbers of the target mRNA with copy numbers of β-actin (a housekeeping gene), which remained constant under different treatment conditions. The β-actin mRNAs of the control were examined in every PCR plate to eliminate any systematic error. Relative quantification was performed using the 2−∆∆Ct method.

Developmental Time and Fecundity of B. tabaci

To assess the impact of O3, TYLCV, and tomato genotype on B. tabaci MED developmental time, four tomato plants of uniform size were randomly selected within each OTC. And three pairs of whitefly adults were placed in a clip cage (3.5 cm diameter, 1.5 cm height) attached to the tomato leaf per tomato plant. The adults were removed after 24 h of infestation, and total 45 eggs were left. The developmental status of the offspring B. tabaci was recorded using a microscope daily until adult eclosion every day. The bioassay of developmental time was conducted from the egg stage until adult eclosion (about 25 d).

To assess the impact of O3, TYLCV, and tomato genotype on B. tabaci MED fecundity, tomato plants of uniform size were randomly selected within each OTC. Twenty pairs of newly emerged B. tabaci MED adults were transferred to clip cage (3.5 cm diameter, 1.5 cm height) attached to the tomato leaves, respectively. If a male died, another healthy male was immediately added. The fecundity of each individual whitefly was recorded daily. The bioassay of whitefly fecundity was persistently conducted until female died (about 40 d).

Statistical Analyses

A split–split plot design and statistical model were used in the experiment. The main effects of O3, TYLCV, and tomato genotype on plant and MED performance (amino acids content, SA and related gene, JA and related gene, developmental time and fecundity of B. tabaci) were tested. Differences among means were determined using Tukey's test at P < 0.05. Pearson's correlations were calculated to analyze the relationships between the B. tabaci performance and biochemical indices of tomato plants. All raw data sets meet the assumptions of Gaussian distribution and homoscedasticity with no transformation.

Results

The Effect of Elevated O3 Levels on Tomato Biochemical Properties, MED Developmental Time, and Fecundity

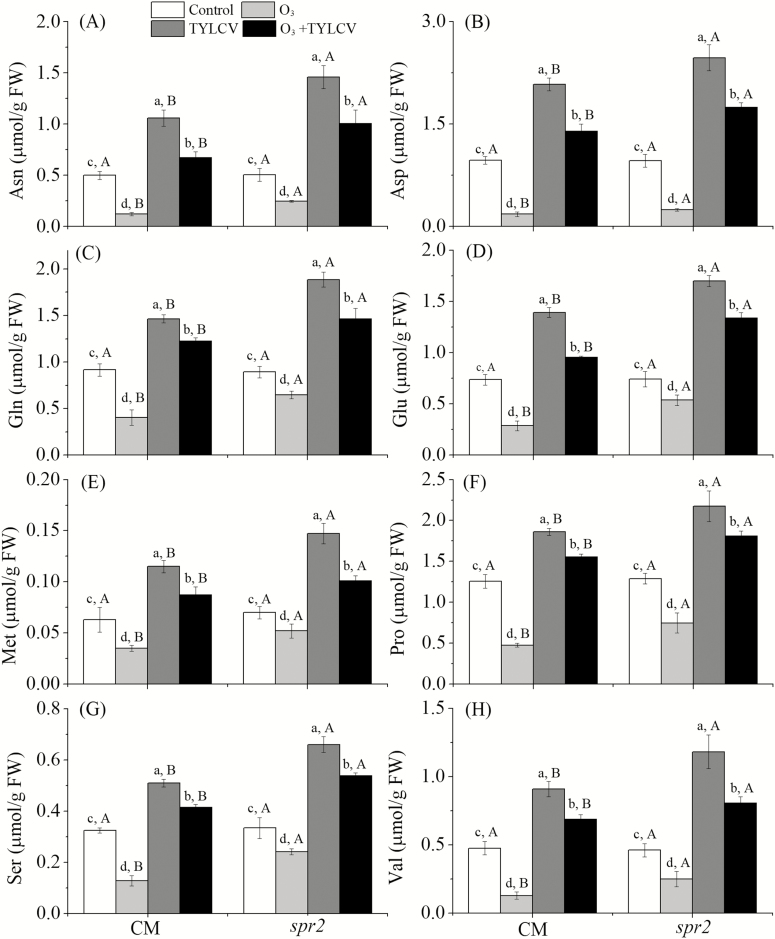

To determine amino acids content in tomato plants, three replicates of tomato sampling were analyzed. Elevated O3 levels decreased the concentrations of Ala, Arg, Cys, Gly, Ile, Leu, Lys, Phe, and Trp (Supp Table 2 [online only], Supp Fig. 1 [online only]). Elevated O3 concentrations significantly decreased the levels of Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Met, Pro, Ser, and Val from a range of 44.4–81.4% in the CM plant and from a range of 25.7–74.4% in the spr2 plant (Table 1, Fig. 1A–H).

Table 1.

Effects of O3 level, TYLCV infection, and plant genotype on tomato amino acid content

| Factor | Asn | Asp | Gln | Glu | Met | Pro | Ser | Val |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TYLCV | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Tomato genotype | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| O3 × TYLCV | 0.118 | 0.543 | 0.400 | 0.105 | 0.031 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.714 |

| O3× Genotype | 0.650 | 0.834 | 0.469 | 0.001 | 0.443 | 0.264 | 0.046 | 0.817 |

| TYLCV × Genotype | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.129 | 0.102 | 0.001 | 0.012 |

| O3× TYLCV × Genotype | 0.158 | 0.480 | 0.001 | 0.068 | 0.035 | 0.065 | 0.002 | 0.011 |

P values from ANOVA are shown. Asn (asparagine); Asp (aspartic acid); Gln (glutamine); Glu (glutamic acid); Met (methionine); Pro (proline); Ser (serine); Val (valine).

Fig. 1.

Concentrations of (A) asparagine (Asn), (B) aspartic acid (Asp), (C) glutamine (Gln), (D) glutamic acid (Glu), (E) methionine (Met), (F) proline (Pro), (G) serine (Ser), and (H) valine (Val) in the two tomato genotypes (CM, spr2) grown under ambient and elevated O3 levels with and without TYLCV infection after 4 wk. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments in the same tomato plant, and different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two tomato genotypes within the same treatment (Tukey's test: P < 0.05).

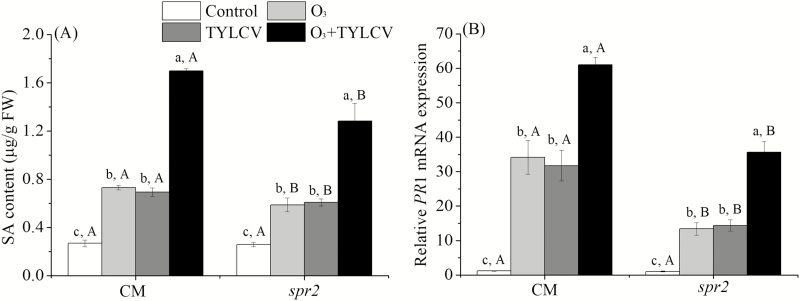

To determine SA content and related gene PR1 in tomato plants, three replicates of tomato sampling were analyzed. Elevated O3 levels increased SA content and the relative expression of PR1 mRNA by 1.7- and 28.4-fold, respectively, in the CM genotype and by 1.3- and 12.3-fold, respectively, in the spr2 genotype (Table 2, Fig. 2A and B).

Table 2.

Effects of O3 level, TYLCV infection, and plant genotype on Bemisia tabaci MED developmental time and fecundity and biochemical properties of tomato

| Factor | SA | JA | PR1 | PI1 | Developmental time | Fecundity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TYLCV | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Tomato genotype | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| O3 × TYLCV | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.272 | <0.001 | 0.406 | <0.001 |

| O3 × genotype | <0.001 | 0.875 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.663 | 0.816 |

| TYLCV × genotype | 0.003 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.406 | 0.098 |

| O3 × TYLCV × genotype | 0.058 | 0.209 | 0.015 | 0.030 | 0.452 | 0.245 |

P values from ANOVA are shown. SA (salicylic acid), JA (jasmonic acid); PR1 (pathogenesis-related protein); PI1 (proteinase inhibitor).

Fig. 2.

Concentrations of (A) salicylic acid (SA) and relative expression of gene encoding (B) pathogenesis-related protein (PR1) in the two tomato genotypes (CM, spr2) grown under ambient and elevated O3 levels with and without TYLCV infection after 4 wk. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments in the same tomato plant, and different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two tomato genotypes within the same treatment (Tukey's test: P < 0.05).

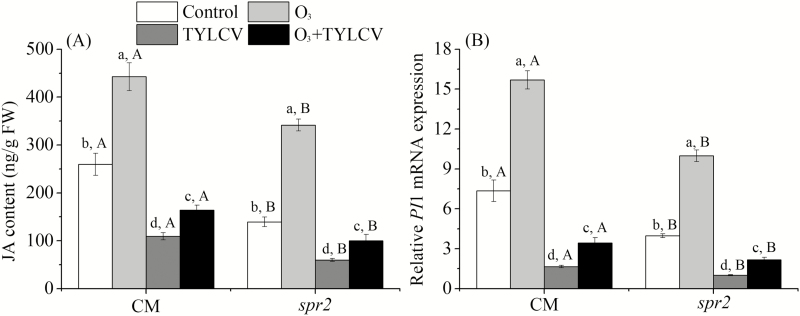

To determine JA content and related gene PI1 in tomato plants, three replicates of tomato sampling were analyzed. Elevated O3 concentration increased JA content and the relative expression of PI1 mRNA by 70.5% and 1.1-fold, respectively, in the CM plant and by 1.4- and 1.5-fold, respectively, in the spr2 plant (Table 2, Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 3.

Concentrations of (A) jasmonic acid (JA) and relative expression of gene encoding (B) proteinase inhibitor (PI1) in the two tomato genotypes (CM, spr2) grown under ambient and elevated O3 levels with and without TYLCV infection after 4 wk. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments in the same tomato plant, and different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two tomato genotypes within the same treatment (Tukey's test: P < 0.05).

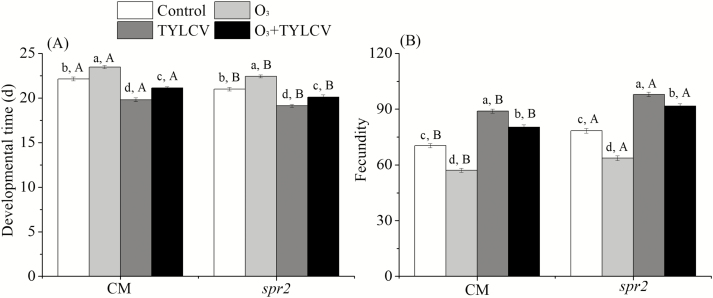

To determine the developmental time of whitefly MED, 45 replicates of eggs were observed. Elevated O3 concentration significantly increased the developmental time by 6.1% in the CM genotype and by 6.8% in the spr2 plant (Table 2, Fig. 4A). Twenty pairs of emerged whiteflies MED were observed to analyze the fecundity. Elevated O3 concentration significantly decreased the fecundity by 18.8% in the CM genotype and by 18.9% in the spr2 plant (Table 2, Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Developmental time (A) and fecundity (B) of Bemisia tabaci MED reared on two tomato genotypes (Wt, spr2) grown under ambient and elevated O3 levels with and without TYLCV infection. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the four treatments in the same tomato plant, and different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two tomato genotypes within the same treatment (Tukey's test: P < 0.05).

The Effect of TYLCV Infection on Tomato Biochemical Properties, MED Developmental Time, and Fecundity

TYLCV infection decreased the concentrations of Ala, Arg, Cys, Gly, Ile, Leu, Lys, Phe, and Trp (Supp Table 2 [online only], Supp Fig. 1 [online only]). When the plants were infected with TYLCV, elevated O3 levels increased the levels of Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Met, Pro, Ser, and Val from a range of 23.9–44.6%, in the CM plant and from a range of 40.4–99.2%, in the spr2 plant (Fig. 1A–H). Regardless of O3 concentration, TYLCV infection significantly increased the levels of Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Met, Pro, Ser, and Val in both genotypes (Fig. 1A–H).

When the plants were infected with TYLCV, elevated O3 levels increased the SA content and the relative expression of PR1 mRNA by 5.3- and 51.7-fold, respectively, in the CM genotype and by 3.9- and 34.4-fold, respectively, in the spr2 genotype, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). The SA content and gene expression of PR1 were highest with the O3 + TYLCV infection treatment for both genotypes (Fig. 2A and B).

When the plants were infected with TYLCV, elevated O3 concentration decreased the JA content and the relative expression of PI1 mRNA by 36.7 and 53.2%, respectively, in the CM genotype and by 28.2 and 45.3%, respectively, in the spr2 genotype (Fig. 3A and B). Regardless of O3 concentration, TYLCV infection significantly decreased the JA content and the relative expression of PI1 mRNA in both genotypes (Fig. 3A and B).

When the plants were infected with TYLCV, elevated O3 levels decreased the developmental time by 4.6% in the CM genotype and by 4.3%, respectively, in the spr2 plant (Fig. 4A). When the plants were infected with TYLCV, elevated O3 concentration increased the fecundity by 14.2% in the CM genotype and by 16.8% in the spr2 plant (Fig. 4B). Regardless of O3 concentration, TYLCV infection significantly decreased the B. tabaci developmental time and increased fecundity in both genotypes (Fig. 4A and B).

The Effect of Tomato Genotypes on Tomato Biochemical Properties, MED Developmental Time, and Fecundity

The levels of Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Met, Pro, Ser, and Val were lower in the CM plants than in the spr2 plants under elevated O3 concentration, TYLCV infection, and the combined treatment (Fig. 1A–H). CM plants exhibited higher SA content and relative expression of PR1 mRNA than spr2 plants under elevated O3 concentrations, TYLCV infection, and the combined treatment (Fig. 2A and B). The JA content and the relative expression of PI1 mRNA were higher in the CM plants than in the spr2 plants under the four treatments (Fig. 3A and B). The B. tabaci developmental time was longer, and the fecundity was lower in the CM plants than in the spr2 plants under the four treatments (Fig. 4A and B).

Correlations Between the Performance of B. tabaci and Biochemical Indices of Tomato

The rate of development and the fecundity of MED were positively correlated with amino acid content, including the levels of Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Met, Pro, Ser, and Val, and negatively correlated with JA content and relative PI1 mRNA expression (Table 3). There was no significant correlation between whitefly developmental time and fecundity and SA content, relative PR1 mRNA expression, and partial amino acid levels (including Ala, Arg, Cys, Gly, His, Ile, Leu, Lys, Phe, Thr, Try, Tyr; Supp Table 3 [online only]).

Table 3.

Pearson correlations between Bemisia tabaci MED developmental time and fecundity and biochemical properties of tomato leaves

| Tomato constituents | Developmental time | Fecundity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| JA | 0.965 | <0.001 | −0.966 | <0.001 |

| PI1 | 0.948 | <0.001 | −0.943 | <0.001 |

| Asn | −0.961 | <0.001 | 0.968 | <0.001 |

| Asp | −0.959 | <0.001 | 0.969 | <0.001 |

| Gln | −0.963 | <0.001 | 0.976 | <0.001 |

| Glu | −0.971 | <0.001 | 0.975 | <0.001 |

| Met | −0.965 | <0.001 | 0.961 | <0.001 |

| Pro | −0.971 | <0.001 | 0.984 | <0.001 |

| Ser | −0.973 | <0.001 | 0.984 | <0.001 |

| Val | −0.960 | <0.001 | 0.967 | <0.001 |

JA (jasmonic acid); PI1 (proteinase inhibitor); Asn, (asparagine); Asp (aspartic acid); Gln (glutamine); Glu (glutamic acid); Met (methionine); Pro (proline); Ser (serine); Val (valine).

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that the interactive effects of elevated O3 levels and viral infection can enhance the population fitness of whitefly fed on tomato plants in terms of developmental time and fecundity. The altered insect performance was due to the O3-induced responses of tomato plants being differentially influenced by TYLCV infection. Elevated O3 levels without viral infection decreased the amino acid content, increased the JA content and gene expression levels of PI1 in both tomato genotypes, and decreased the performance of MED fed on the two tomato plants. In contrast, viral infection under elevated O3 levels increased the amino acid content, decreased the JA content and the gene expression levels of PI1, and increased the performance of MED fed on the two tomato plants. Furthermore, the performance of MED was in association with spr2 plants was better than that with CM plants, suggesting that the difference in the JA signaling pathway between the plant genotypes had a significant effect on the performance of the whitefly MED. MED performance was positively correlated with amino acid content and negatively correlated with JA content and relative PI1 mRNA expression, suggesting that the interactive effects of elevated O3 levels and viral infection enhanced the performance of the MED vector insects via bottom-up effects of the host plants.

Previous studies showed that elevated O3 levels could decrease nutritional content and increase levels of defensive-related substances in plant tissues (Ye et al. 2012, Cui et al. 2012). Excessive production of ROS can disrupt plant metabolism and thus leading to irreversible injury to plasma membrane and nutrients (Apel and Hirt 2004). Furthermore, ROS leads to activation of defense signaling pathways and the accumulation of secondary metabolites in response to elevated O3 concentration (Simon et al. 2010, Ye et al. 2012). For example, elevated O3 levels significantly decreased the total amino acid content of tobacco plants (Ye et al. 2012). Elevated O3 levels induced the accumulation of both JA and SA and upregulated the expression of the associated marker genes (Pazarlar et al. 2017). Similarly, in our study, elevated O3 levels significantly decreased the amino acid content and increased the JA and SA levels and related defensive gene expression in both CM and spr2 tomato plants. Among herbivorous insects, the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae, exhibited lower population growth rates when exposed to elevated O3 levels than when exposed to ambient O3 (Menendez et al. 2010). Relatively few eggs and larvae of the leaf beetle, Agelastica coerulea, were found when these insects were fed O3-exposed plants (Inoue et al. 2016). It was suggested that increased O3 levels are disadvantageous to the performance of both phloem-sucking insects and chewing insects. Likewise, the MED whitefly negatively affected by elevated O3 levels, which is consistent with the increased developmental duration and decreased fecundity. Previous studies also showed that secondary metabolism can negatively affect the performance of piercing-sucking insects (Walling 2000, Yan et al. 2018). For example, total phenolics and condensed tannins decreased whitefly population densities, growth rate, and delayed developmental time (Mansour et al. 1997, Bialczyk et al. 1999). We assumed that whitefly could be more vulnerable to total phenolics and condensed tannins because elevated O3 could accumulate these secondary metabolites in plant tissue (Cui et al. 2012).

Plant viruses could indirectly alter the behavior and performance of the insect vectors through the host plant mutualistically or antagonistically (Liu et al. 2013). Viral infection can change the primary and secondary compounds as well as resistance-related substances produced by the host plant, which in turn could differentially affect the performance of B. tabaci MED and MEAM1 (Shi et al. 2014, Sun et al. 2017). In our study, we also found that TYLCV infection significantly increased MED fecundity and shortened the developmental time. TYLCV can be transmitted by B. tabaci in a persistent and circulative manner (Ghanim 2014). Persistent and circulative viruses can increase nutritional assimilation. Viral infection of tobacco with tomato yellow leaf curl China virus (TYLCCNV) improves the amino acid content, and the vector performs better on virus-infected tomato than on uninfected controls (Wang et al. 2012). Our results also showed that TYLCV infection led to an unequal increase in the amino acid content of tomato plants. The interactions between pathogenicity factor ßC1 and MYC2 can suppress terpenoid synthesis and release via repressing the JA signaling pathway (Luan et al. 2013, Bingham et al. 2014). JA-induced defenses in plants were shown to confer resistance to whitefly (Su et al. 2016). In our study, TYLCV infection significantly suppressed the JA content and the expression of related defensive genes. Further research showed that the combination of elevated O3 levels and TYLCV infection shortened the developmental time of MED and increased the fecundity in the two tomato plants compared with the control plants. The results showed that the increased population growth of MED on TYLCV-infected tomato plants promotes diffusion and spread of the MED vectors, which carry the virus to new place under elevated O3 levels. This finding suggests that the virus offsets the adverse effects of elevated O3 levels on vector performance. In other words, the vector or virus may manipulate the host plant for its own benefit under elevated O3 levels.

The JA defense-enhanced tomato genotype 35S exhibits a stronger JA signal and greater resistance than the wild-type plant, whereas JA-deficient mutants exhibit reduced resistance against insects (Zarate et al. 2007, Wei et al. 2011). For example, JA-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana accelerate silverleaf whitefly nymphal development compared to wild-type plants (Zarate et al. 2007). The whitefly egg counts improved on JA-deficient tomato plants than on wild-type tomato plants (Sun et al. 2017). In our results, the MED whitefly exhibited lower fecundity and longer developmental time in association with CM plants than with spr2 plants regardless of O3 levels and viral infection, indicating that diminished JA-dependent defenses were responsible for improved performance. This study suggests that whiteflies would be more successful at infesting TYLCV-infected plants than at infesting uninfected plants in environments with elevated O3 levels. It suggests that the environmental carrying capacity with respect to whiteflies will gradually increase with the increasing O3 concentration and viral infection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at Environmental Entomology online.

Supplementary Table S1. Sequences of primers used for real-time quantitative PCR.

Supplementary Table S2. Effects of O3 level, TYLCV infection, and plant genotype on amino acid content in tomato. P values from ANOVA are shown.

Supplementary Table S3. Pearson correlations between B. tabaci developmental time and fecundity and biochemical properties of tomato leaves.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Concentrations of (A) alanine (Ala), (B) arginine (Arg), (C) cysteine (Cys), (D) glycine (Gly), (E) histidine (His), (F) isoleucine (Ile), (G) leucine (Leu), (H) lysine (Lys), (I) phenylalanine (Phe), (J) threonine (Thr), (K) tryptophan (Trp), and (L) tyrosine (Tyr) in the two tomato genotypes (CM, spr2) grown under ambient and elevated O3 levels with and without TYLCV infection after 4 weeks.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31601637), the Beijing Key Laboratory for Pest Control and Sustainable Cultivation of Vegetables and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-IVFCAAS). We thank Prof. Chuanyou Li (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Science) for providing the two tomato genotypes, and we thank Prof. Xueping Zhou (Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for providing the infectious clone of TYLCV. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References Cited

- Agrell J., Kopper B., McDonald E. P., and Lindroth R. L.. . 2005. CO2 and O3 effects on host plant preferences of the forest tent caterpillar (Malacosoma disstria). Global Change Biol. 11: 588–599. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth E. A., Yendrek C. R., Sitch S., Collins W. J., and Emberson L. D.. . 2012. The effects of tropospheric ozone on net primary productivity and implications for climate change. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63: 637–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel K., and Hirt H.. . 2004. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55: 373–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialczyk J., Lechowski Z., and Libik A.. . 1999. The protective action of tannins against glasshouse whitefly in tomato seedlings. J. Agric. Sci. 133: 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin D. D., Aldea M., O'Neill B. F., Benitez M., Li M., Clough S. J., and DeLucia E. H.. . 2008. Elevated ozone alters soybean-virus interaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21: 1297–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham G., Alptekin S., Delogu G., Gurkan O., and Moores G.. . 2014. Synergistic manipulations of plant and insect defences. Pest Manag. Sci. 70: 566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blande J. D., Holopainen J. K., and Li T.. . 2010. Air pollution impedes plant-to-plant communication by volatiles. Ecol. Lett. 13: 1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D., Wan F. H., Zhang Y. J., and Brown J. K.. . 2010. Change in the biotype composition of Bemisia tabaci in Shandong Province of China from 2005 to 2008. Environ. Entomol. 39: 1028–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U., Beckers G. J. M., Flors V., Garcia-Agustin P., Jakab G., Mauch F., Newman M. A., Pieterse C. M. J., Poinssot B., Pozo M. J., . et al. 2006. Priming: getting ready for battle. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19: 1062–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H. Y., Sun Y. C., Su J. W., Ren Q., Li C. Y., and Ge F.. . 2012. Elevated O3 reduces the fitness of Bemisia tabaci via enhancement of the SA-dependent defense of the tomato plant. Arthropod-Plant Int. 6: 425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Cui H. Y., Su J. W., Wei J. N., Hu Y. J., and Ge F.. . 2014. Elevated O3 enhances the attraction of whitefly-infested tomato plants to Encarsia formosa. Sci. Rep. 4: 5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H. Y., Sun Y. C., Chen F. J., Zhang Y. J., and Ge F.. . 2016. Elevated O3 and TYLCV infection reduce the suitability of tomato as a host for the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17: 1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H., Guo L., Wang S., Xie W., Jiao X., Wu Q., and Zhang Y.. . 2017. The ability to manipulate plant glucosinolates and nutrients explains the better performance of Bemisia tabaci Middle East-Asia Minor 1 than Mediterranean on cabbage plants. Ecol. Evol. 7: 6141–6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui F., Wu H., Safronov O., Zhang P., Kumar R., Kollist H., Salojärvi J., Panstruga R., and Overmyer K.. . 2018. Arabidopsis MLO2 is a negative regulator of sensitivity to extracellular reactive oxygen species. Plant Cell Environ. 41: 782–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrecht B., Xue G. P., Sprague S. J., Kirkegaard J. A., Ross J. J., Reid J. B., Fitt G. P., Sewelam N., Schenk P. M., Manners J. M., . et al. 2007. MYC2 differentially modulates diverse jasmonate-dependent functions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2225–2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost C. J., Mescher M. C., Carlson J. E., and De Moraes C. M.. . 2008. Plant defense priming against herbivores: getting ready for a different battle. Plant Physiol. 146: 818–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanim M. 2014. A review of the mechanisms and components that determine the transmission efficiency of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (Geminiviridae; Begomovirus) by its whitefly vector. Virus Res. 186: 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanim M., Sobol I., Ghanim M., and Czosnek H.. . 2007. Horizontal transmission of begomoviruses between Bemisia tabaci biotypes. Arthropod-Plant Int. 1: 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Sun Y., Peng X., Wang Q., Harris M., and Ge F.. . 2016. Up-regulation of abscisic acid signaling pathway facilitates aphid xylem absorption and osmoregulation under drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 67: 681–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. G., Wan S. F., and Ge F.. . 2017. Effect of elevated CO2 and O3 on phytohormone-mediated plant resistance to vector insects and insect-borne plant viruses. Sci. China Life Sci. 60: 816–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Ren Q., Sun Y., Ye L., Cao H., and Ge F.. . 2012. Lower incidence and severity of tomato virus in elevated CO2 is accompanied by modulated plant induced defence in tomato. Plant Biol. (Stuttg) 14: 905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue W. A., Vanderstock T., Sakikawa M., Nakamura H., Saito M., Shibuya 2016. The interaction between insects and deciduous broadleaved trees under different O3 concentrations and soil fertilities. Boreal For Res. 64: 30. [Google Scholar]

- (IPCC) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. Climate change 2014: synthesis report, pp. 151 InPachauri R., and Meyer L. (eds.), Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Liu G., Xu C., Lee G., Bauer P., Ganal M., and Howe G. A.. . 2003. The tomato suppressor of prosystemin-mediated responses2 gene encodes a fatty acid desaturase required for the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid and the production of a systemic wound signal for defense gene expression. Plant Cell 15: 646–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Weldegergis B. T., Li J., Jung C., Qu J., Sun Y., Qian H., Tee C., van Loon J. J., Dicke M., . et al. 2014. Virulence factors of geminivirus interact with MYC2 to subvert plant resistance and promote vector performance. Plant Cell 26: 4991–5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Preisser E. L., Chu D., Pan H., Xie W., Wang S., Wu Q., Zhou X., and Zhang Y.. . 2013. Multiple forms of vector manipulation by a plant-infecting virus: Bemisia tabaci and tomato yellow leaf curl virus. J. Virol. 87: 4929–4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan J. B., Yao D. M., Zhang T., Walling L. L., Yang M., Wang Y. J., and Liu S. S.. . 2013. Suppression of terpenoid synthesis in plants by a virus promotes its mutualism with vectors. Ecol. Lett. 16: 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour M. H., Zohdy N. M., El-Gengaihi S. E., Amr A. E. 1997. The relationship between tannins concentration in some cotton varieties and susceptibility to piercing sucking insects. J. Appl. Entomol. 121: 321–325. [Google Scholar]

- Menendez A. I., Romero A. M., Folcia A. M., and Martinez-Ghersaet M. A.. . 2010. Aphid and episodic O3 injury in arugula plants (Eruca sativa Mill) grown in open-top field chambers. Agric. Ecosys. Environ. 135: 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Overmyer K., Wrzaczek M., and Kangasjärvi J.. . 2009. Reactive oxygen species in ozone toxicity, pp. 191–207. InRio L. A., and Puppo A. (eds.), Reactive oxygen species in plant signaling. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Pazarlar S., Cetinkaya N., Bor M., and Ozdemir F.. . 2017. Ozone triggers different defence mechanisms against powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis DC. Speer f. sp. tritici) in susceptible and resistant wheat genotypes. Funct. Plant Biol. 44: 1016–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M. V., Lee H., Creelman R. A., Mullet J. E., and Davis K. R.. . 2000. Jasmonic acid signaling modulates ozone-induced hypersensitive cell death. Plant Cell 12: 1633–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Q., Luo C., Zhang H., Guo X., and Devine G. J.. . 2011. Distribution and dynamics of Bemisia tabaci invasive biotypes in central China. Bull. Entomol. Res. 101: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Pan H., Xie W., Jiao X., Fang Y., Chen G., Yang X., Wu Q., Wang L. S., and Zhang Y.. . 2014. Three-way interactions between the tomato plant, tomato yellow leaf curl virus, and Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) facilitate virus spread. J. Econ. Entomol. 107: 920–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C., Langlois-Meurinne M., Bellvert F., Garmier M., Didierlaurent L., Massoud K., Chaouch S., Marie A., Bodo B., Kauffmann S., . et al. 2010. The differential spatial distribution of secondary metabolites in Arabidopsis leaves reacting hypersensitively to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato is dependent on the oxidative burst. J. Exp. Bot. 61: 3355–3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansley P. A., and Naranjo S. E.. . 2010. Bemisia: bionomics and management of a global pest. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Su Q., Mescher M. C., Wang S., Chen G., Xie W., Wu Q., Wang W., and Zhang Y.. . 2016. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus differentially influences plant defence responses to a vector and a non-vector herbivore. Plant. Cell Environ. 39: 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Guo H., Zhu-Salzman K., and Ge F.. . 2013. Elevated CO2 increases the abundance of the peach aphid on Arabidopsis by reducing jasmonic acid defenses. Plant Sci. 210: 128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. C., Pan L. L., Ying F. Z., Li P., Wang X. W., and Liu S. S.. . 2017. Jasmonic acid-related resistance in tomato mediates interactions between whitefly and whitefly-transmitted virus. Sci. Rep. 7: 566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thines B., Katsir L., Melotto M., Niu Y., Mandaokar A., Liu G., Nomura K., He S. Y., Howe G. A., and Browse J.. . 2007. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCFCOI1 complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 448: 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walling L. L. 2000. The myriad plant responses to herbivores. J. Plant Growth Reg. 19: 195–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Bing X. L., Li M., Ye G. Y., and Liu S. S.. . 2012. Infection of tobacco plants by a begomovirus improves nutritional assimilation by a whitefly. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 144: 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C., and Hause B.. . 2013. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 111: 1021–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Wang L., Zhao J., Li C., Ge F., and Kang L.. . 2011. Ecological trade-offs between jasmonic acid-dependent direct and indirect plant defences in tritrophic interactions. New Phytol. 189: 557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Guo H., Yuan E., Sun Y., and Ge F.. . 2018. Elevated CO2 and O3 alter the feeding efficiency of Acyrthosiphon pisum and Aphis craccivora via changes in foliar secondary metabolites. Sci. Rep. 8: 9964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Y., Iwasaki M., Machida C., Machida Y., Zhou X., and Chua N. H.. . 2008. betaC1, the pathogenicity factor of TYLCCNV, interacts with AS1 to alter leaf development and suppress selective jasmonic acid responses. Genes Dev. 22: 2564–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N., Wang X., Zheng F., and Chen Y.. . 2017. The response of marigold (Tagetes erecta Linn.) to ozone: impacts on plant growth and leaf physiology. Ecotoxicology 26: 151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L., Fu X., and Ge F.. . 2012. Enhanced sensitivity to higher ozone in a pathogen-resistant tobacco cultivar. J. Exp. Bot. 63: 1341–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X., Calatayud V., Gao F., Fares S., Paoletti E., Tian Y., and Feng Z.. . 2016. Interaction of drought and ozone exposure on isoprene emission from extensively cultivated poplar. Plant. Cell Environ. 39: 2276–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate S. I., Kempema L. A., and Walling L. L.. . 2007. Silverleaf whitefly induces salicylic acid defenses and suppresses effectual jasmonic acid defenses. Plant Physiol. 143: 866–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. P., Zhang Y. J., Zhang W. J., Wu Q. J., Xu B. Y., and Chu D.. . 2005. Analysis of genetic diversity among different geographical populations and determination of biotypes of Bemisia tabaci in China. J. Appl. Entomol. 129: 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Luan J. B., Qi J. F., Huang C. J., Li M., Zhou X. P., and Liu S. S.. . 2012. Begomovirus-whitefly mutualism is achieved through repression of plant defences by a virus pathogenicity factor. Mol. Ecol. 21: 1294–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. J., Broekgaarden C., Zheng S. J., Snoeren T. A., van Loon J. J., Gols R., and Dicke M.. . 2013. Jasmonate and ethylene signaling mediate whitefly-induced interference with indirect plant defense in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 197: 1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Xu B., Wu T., Wen M. X., Fan L. X., Feng Z. Z., and Paoletti E.. . 2017. Transcriptomic analysis of Pak Choi under acute ozone exposure revealed regulatory mechanism against ozone stress. BMC Plant Biol. 17: 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. P., Zhang H., and Gong H. R.. . 2009. Molecular characterization and pathogenicity of tomato yellow leaf curl virus in China. Virus Genes 39: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.