Abstract

Lung is one of the most common sites to which almost all other primary tumors metastasize. The major challenges in the chemotherapy of lung metastases include the low drug concentration found in the tumors and high systemic toxicity upon systemic administration. In this study, we combine local lung delivery and the use of nanocarrier-based systems for improving pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of the therapeutics to fight lung metastases. We investigate the impact of the conjugation of doxorubicin (DOX) to carboxyl-terminated poly(amidoamine) dendrimers (PAMAM) through a bond that allows for intracellular-triggered release, and the effect of pulmonary delivery of the dendrimer–DOX conjugate in decreasing tumor burden in a lung metastasis model. The results show a dramatic increase in efficacy of DOX treatment of the melanoma (B16-F10) lung metastasis mouse model upon pulmonary administration of the drug, as indicated by decreased tumor burden (lung weight) and increased survival rates of the animals (male C57BL/6) when compared to iv delivery. Conjugation of DOX further increased the therapeutic efficacy upon lung delivery as indicated by the smaller number of nodules observed in the lungs when compared to free DOX. These results are in agreement with the biodistribution characteristics of the DOX upon pulmonary delivery, which showed a longer lung accumulation/retention compared to iv administration. The distribution of DOX to the heart tissue is also significantly decreased upon pulmonary administration, and further decreased upon conjugation. The results show, therefore, that pulmonary administration of DOX combined to conjugation to PAMAM dendrimer through an intracellular labile bond is a potential strategy to enhance the therapeutic efficacy and decrease systemic toxicity of DOX.

Keywords: Polyamidoamine dendrimer, doxorubicin, pulmonary delivery, lung cancer, controlled intracellular release, cardiac toxicity

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the second most common cause of death for both men and women in the United States, second only to heart diseases.1 Among the many malignant tumors, lung cancers are the leading cause of death. More patients die from lung cancers than breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers combined.2 Although curative surgery is the first choice in the clinic for treating primary lung tumors, chemotherapy plays a vital role in inhibiting tumor growth after surgery, partly due to the high rates of recurrence.3,4 Additionally, the lungs are the most common site for metastasis for almost all other primary tumors.5 Metastatic tumors are also associated with more than 90% of cancer-related deaths.6 The development of new strategies that can help improve chemotherapeutic outcomes during the treatment of lung metastasis may have, therefore, a significant societal impact.

One of the major challenges limiting the success of systemically administered chemotherapeutics in the treatment of lung metastases is the low concentration of anticancer agents in the lung tissue and lung tumor.7–9 Upon systemic administration, such as intravenous injection (iv), only a few percent of the total dose (TD) (<ca. 4%) actually reaches the tumor site.9 Because of typical systemic toxicity of anticancer therapeutics, increasing the overall administered dose so as to reach therapeutic local concentration of chemotherapeutics is usually not a viable strategy.10 The study of the effectiveness of new chemotherapeutic strategies that consider local lung delivery is, therefore, also of great potential relevance as these strategies promote local drug concentration while decreasing systemic exposure.

Doxorubicin (DOX) is one of the most effective anticancer therapeutics available in the clinic today11 and has been widely used alone or in combination to treat a variety of cancers including lung cancers.12–14 DOX induces the apoptosis of cancer cells by intercalating itself to DNA double helix and thus inhibiting the progression of enzyme topoisomerase II. Other mechanisms include the production of high level reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cellular membrane disruption.15 The applicability of DOX is to some extent limited, however, due to its toxicity to the cardiac tissue.16 The accumulation of DOX in the heart results in increased oxidative stress, downregulated protein function, decreased cardiac gene expression, and upregulated apoptosis of cardiomyocytes, which may eventually lead to lethal cardiomyopathy.17

There are, therefore, tremendous opportunities in the development of strategies that will enhance the local concentration of DOX in the lung tissue, while maximizing its intracellular delivery to lung tumor cells, and at the same time minimizing the systemic concentration of free DOX. Pulmonary administration of a nanocarrier-based DOX delivery system is uniquely suited in this aspect and has been evaluated in vivo in the treatment of lung cancers, including DOX-loaded lactose particles,18 DOX-loaded poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) nanoparticles,19 acid-sensitive dendritic polylysine–DOX (PLL–DOX) conjugates,20 and acid-sensitive poly-(ethylene imine)–DOX (PEI–DOX) conjugates.21 These delivery systems administered via pulmonary route show the potential to reduce lung metastasis burden and also reduce lung and systemic toxicity. Dendrimers are particularly interesting drug carriers as they are highly monodispersed (predictable pharmacokinetics/biodistribution) and can be easily functionalized with therapeutic agents through linkages that allow for temporal and spatial control of drug release, in a similar fashion as hyperbranched polymers. Dendrimers can also be modified with various ligands to control their interaction with the physiological environment and can also promote their cellular internalization.22–24 Commercially available poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers have been widely used as drug delivery nanocarriers.22 However, PAMAM–doxorubicin (PAMAM–DOX) delivery systems have not been evaluated in the treatment of lung metastasis upon pulmonary administration. The morphology, size, chemistry, and surface chemistry of nanomaterials greatly affect how they interact with the physiological environment and are thus expected to behave differently—as for example PEGylated vs non-PEGylated dendrimers,25–27 or an amine-terminated hyperbranched polymer vs a carboxyl-terminated PAMAM.28–30 The effect of route of administration (pulmonary vs systemic route) and conjugation (free or conjugated) on the cardiac accumulation of DOX conjugated to PAMAM dendrimers has not been evaluated either.

Based on the challenges and opportunities discussed earlier, the goal of this study was to investigate the effect of the conjugation of DOX to dendrimer and effect of the local administration of the carrier system to the lung tissue on the efficacy of DOX in reducing the metastatic lung tumor burden. We conjugated DOX to carboxyl-terminated, generation 4, poly(amidoamine) dendrimer (G4COOH) nanocarriers through an intracellular triggered (pH-responsive) drug release linker. Carboxyl-terminated dendrimer was chosen as it has been shown to have lower toxicity compared to its amine-terminated counterpart.24 Yet, using the conjugation strategy for DOX shown here, we are able to retain a positive charge to the overall system so as to enhance cellular uptake.14 We evaluated the impact of pH on the release kinetics of the conjugates, both at extracellular physiological pH (7.4) and at intracellular pH (lysosomal, 4.5). The ability of the conjugates to gain access and kill B16-F10 mouse melanoma cells was also investigated using flow cytometry and MTT assay. A mouse model of lung metastasis (from melanoma B16-F10 cells) was established, and the efficacy of the G4COOH–DOX conjugates in reducing the metastatic lung tumor burden and improving the rate of survival was investigated. The effect of conjugation was assessed by comparing the results of the studies above to free DOX, while the impact of the local lung delivery was determined by comparing the effectiveness of the conjugates and free DOX delivered via pharyngeal aspiration (locally, pulmonary delivery) and intravenous injection (iv). The potential of the conjugation of DOX to G4COOH and the pulmonary delivery route are also discussed in terms of the tissue distribution of the carriers, particularly to the lungs (target) and the cardiac tissue (to be avoided).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials.

Generation 4 succinamic acid surface poly(amidoamine) dendrimer (G4COOH, 64 surface COOH groups) was purchased from Dendritech, Inc. (Midland, MI, USA). Doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX; research grade; purity >99%) was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). Citric acid monohydrate, sodium citrate dihydrate, N-methylmorpholine (NMM), and isobutyl chloroformate (IBCF) were purchased from VWR Internationals (Radnor, PA, USA). tert-Butyl carbamate (TBC), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), triethylamine (TEA), 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,5-DHB), and 4% paraformaldehyde PBS solution were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 1×), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), penicillin (10,000 U/mL)–streptomycin (10,000 μg/mL), Trypan Blue solution (0.4%), and trypsin–EDTA solution (0.25% trypsin and 0.53 mM EDTA) were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals (Flowery Branch, GA, USA). Deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA, USA). Ultrapure deionized water (DI H2O, Ω = 18.0–18.2) was sourced from a Barnstead NANOpure DIamond System (D11911), equipment from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). All anhydrous organic solvents including dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), dimethylformamide (DMF), dichloromethane (DCM), and methanol (MeOH) were bought from VWR Internationals (Radnor, PA, USA). SpectraPor dialysis membrane (MWCO = 3 kDa) was purchased from Spectrum Laboratories, Inc. (Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA). Amicon Ultra 15 centrifugal filter device (MWCO = 10 kDa) was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Thin layer chromatography (TLC) silica gel 60 F254 plastic sheet was purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). All reagents were used as received unless otherwise noted.

2.2. Cell Culture.

Mouse melanoma cell line (B16-F10), passage 5 to 10, was kindly gifted by Dr. Haipeng Liu, Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science at Wayne State University. B16-F10 cells were seeded in a Corning 75 cm2 U-shaped canted neck cell culture flask (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA, USA) and cultured with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin (100 U/mL)–streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (Pen-Strep). The cells were grown in a Thermo Scientific CO2 incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The medium was exchanged every 2 days, and the cells were split as they reached ca. 70–80% confluence.

2.3. Animals for in vivo Experiments.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wayne State University. Male C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks, 20–22 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). The mice were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle, allowed food and water ad libitum, and acclimatized for 1 week prior to the experiments.

2.4. Synthesis and Characterization of Dendrimer–DOX Conjugates with an Acid-Labile Bond (G4COOH–nDOX).

The synthetic route of the G4COOH–nDOX conjugate is shown in Figure 1. The hydrazide groups were introduced to G4COOH dendrimer through TBC, followed by removal of Boc protecting groups. The DOX was then conjugated to the hydrazide-modified dendrimer, forming acid-sensitive hydrazone bonds between DOX and dendrimer. All the intermediates and final products in the reaction were characterized with proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) for chemical composition and mass-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) for molecular weight. The hydrodynamic diameter (HD) and zeta potential (ζ) of the intermediates and final products were measured with light scattering (LS). The methods can be found in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of the generation 4, carboxyl-terminated PAMAM dendrimer (G4COOH) conjugated with acid-labile DOX (G4COOH–nDOX).

G4COOH (78.3 mg, 3.80 μmol) was mixed with NMM (117.98 μL, 1.07 mmol) and IBCF (133.64 μL, 1.02 mmol) in 8 mL of DMSO/DMF (v/v, 10/90). The system was cooled to 0 °C in ice–water slurry and kept stirring for 5 min, and then TBC (32.1 mg, 0.243 mmol) was added to the above mixture.31 The reaction was further stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, and stirring was continued at room temperature for 48 h. The organic solvent was completely removed under reduced pressure. The obtained Boc-protected G4COOH-hydrazide (G4COOH-mTBC) was redissolved in 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution with the pH value being adjusted to around 10. The filtered G4COOH-mTBC was purified with centrifugal filtration (MWCO = 10 kDa), and the product collected in the filter was lyophilized for 24 h. 1H NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ 9.52 (s,32.30H, -NHBoc in TBC), 8.67 (s, 29.58H, -NHCO- in TBC), 7.89–7.70 (m, 156.84H, -NHCO- in G4COOH), 3.06 (m, 372.38H, -CONHCH2- (He) in G4COOH), 2.63–2.56 (m, 328.45H, -NCH2- (Hd) and -COCH2CH2CO (Hjr3) in G4COOH), 2.41 (m, 126.38H, -CH2N- (Hb,c) in G4COOH), 2.29 (m, 150.53H, -CH2CH2CONHNH- (succinic methylene, Hjr2) in G4COOH), 2.18 (m, 248.00H, -CH2CO-(Ha) in G4COOH), 1.36 (m, 305.54H, -(CH3)3 in TBC). MALDI-TOF m/z (Da): 20531.79.

The resulting G4COOH-mTBC (84.34 mg, 4.10 μmol) was dissolved in 5 mL of TFA/DCM (80/20, v/v) and stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. The TFA was immediately removed under reduced pressure. The obtained hydrazide-modified G4COOH dendrimer (G4COOH-mHyd) was treated with 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (pH 10) and then purified with centrifugal filtration (MWCO = 10 kDa). The conjugate collected in the filter was lyophilized for 24 h. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 9.02 (s, 19.06H, NH2NHCO- in hydrazide), 8.03 (m, 175.56H, -NHCO- in G4COOH), 3.05 (m, 258.24H, -CONHCH2- (He) in G4COOH), 2.620 (m, 188.96H, -NCH2- (Hd) and -COCH2CH2CO- (Hjr3) in G4COOH), 2.41 (m, 87.18H, CH2N- (Hb,c) in G4COOH), 2.23 (m, 151.22H, -CH2CONHNH2 (succinic methylene (Hjr2) in G4COOH), 2.18 (m, 248.00H, -CH2CO- (Ha) in G4COOH). MALDI-TOF m/z (Da): 17780.33.

DOX (20 mg, 34.48 μmol) was dissolved in 40 mL of anhydrous MeOH with a trace amount of TFA as catalyst (1.32 μL, 17.32 μmol). The G4COOH-mHyd (18.67 mg, 1.05 μmol) was added to the above organic mixture, and the reaction was monitored with TLC until the reaction was completed. The MeOH was completely removed under reduced pressure. The product was purified with centrifugal filtration (MWCO = 10 kDa) and the solution was monitored for ending of centrifugal process. The product (G4COOH–nDOX) was lyophilized for 24 h. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 9.02 (s, 20.41H, NH2NHCO- in hydrazide), 8.05 (m, 167.13H, -NHCO- and Ar-H in G4COOH and DOX), 5.26 (s, 11.99H, -CH- in DOX), 4.89 (d, 12.72H, -CH- in DOX), 4.17 (s, 11.02H, -CH- in DOX), 3.94 (s, 35.23H, -OCH3 in DOX), 3.05 (m, 255.54H, -CONHCH2- (He) in G4COOH), 2.620 (m, 217.26H, -NCH2-(Hd) and -COCH2CH2CO- (Hjr3) in G4COOH), 2.41 (m, 109.82H, CH2N- (Hb,c) in G4COOH), 2.29 (m, 152.93H, -CH2CONHNH2 (succinic methylene (Hjr1, jr2) in G4COOH), 2.18 (m, 248.00H, -CH2CO- (Ha) in G4COOH), 1.86 and 1.65 (d, 23.96H, -CH2- in DOX), 1.12 (s, 36.10H, -CH3 in DOX). MALDI-TOF m/z (Da): 23860.59.

2.5. In vitro Release of DOX from the G4COOH–nDOX Conjugate.

In vitro release of DOX was determined at both pH 7.4 and 4.5, representing extracellular/physiological pH and lysosomal pH, respectively.32 2.0 mL of PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) or citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5) containing free DOX or G4COOH–12DOX conjugate (both with 1 μmol of DOX or equivalent) was added to a dialysis bag (MWCO = 3 kDa), and the dialysis bag was immersed in 30 mL of the same medium as inside the bag. The In vitro release was performed by gently shaking the system at 37.0 ± 0.2 °C, in darkness and under sink conditions. A 0.1 mL buffer solution from outside the dialysis bag was sampled at predetermined time points, and the absorption of DOX was determined using a Biotek Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc. Winooski, VA, USA), at 490 nm, and the amount of DOX was calculated with respect to an established calibration curve. These experiments were run in triplicate. The samples were returned to outside buffer after each measurement. The cumulative release of DOX from the conjugate was plotted as a function of time.

2.6. Cell Kill (In vitro) of the G4COOH–nDOX Conjugate.

The ability of the G4COOH–12DOX conjugate to kill B16-F10 melanoma cells was assessed using the MTT assay. The results benchmarked against free DOX as control. Briefly, sample-laden DMEM (no phenol red) was sterilized through 0.22 μm syringe filter (VWR Internationals). A 0.1 mL PBS containing 10,000 B16-F10 cells were seeded in each well of tissue culture treated 96-well plate (VWR Internationals) 24 h ahead of the experiment. The DMEM in each well was replaced with a 100 μL of the sample-laden DMEM (10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, no phenol red). The medium was removed after 48 h, and the cells were washed twice with 100 μL PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4). A 100 μL fresh DMEM (no phenol red) and 10 μL MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) were added to each well. After 4 h incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, 75 μL medium was removed and 60 μL DMSO was then added. The cells were allowed to sit in the incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) for another 2 h. Finally, the absorbance of each well was recorded at 570 nm. The cell viability of B16-F10 cells was plotted as a function of free- or dendrimer-conjugated DOX concentration (n = 8 per concentration). A calibration curve correlating absorbance at 570 nm with B16-F10 cell counts was prepared with the same protocol to determine cell death/proliferation. The calibration curve takes into account any potential solution turbidity.

2.7. Cellular internalization of the G4COOH–nDOX conjugate by B16-F10 cells.

A 0.5 mL PBS containing 3 × 105 B16-F10 cells was seeded each well in Costar 24-well cell culture plate (Corning Life Science, Tewksbury, MA, USA) 24 h prior to the experiment. A 0.5 mL sterile Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, 1X, pH 7.4) containing free DOX or G4COOH–12DOX (1 μM DOX or equivalent concentration of conjugated DOX) was added to each well and then incubated with cells for different times (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h; n = 3 per time point). The cellular internalization was terminated at each time point by washing the cells with cold HBSS (1×, pH 7.4). The cells were detached with 0.2 mL of trypsin–EDTA and were then pelleted by centrifugation at 350g. The extracellular fluorescence of DOX was quenched with 0.2% Trypan Blue solution for 5 min in darkness, and the cells were washed twice with cold HBSS cells.8,25 The collected cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL of cold HBSS and immediately analyzed for DOX fluorescence with BD LSR II Analyzer with excitation/emission = 488/590 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). At least 10,000 events were counted for statistical significance. Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was plotted as a function of time to evaluate the cellular internalization of free DOX and dendrimer conjugates. We also calculated the initial rate of internalization, which is a slope obtained by the linear fitting of the dots (MFI, time) at 0, 0.5, and 1 h. The unit of initial rate of internalization is absorbance unit/hour (AU h−1).

2.8. Efficacy of Free and Dendrimer-Conjugated DOX in Treating Lung Metastasis.

200 μL of PBS containing 2 × 105 B16-F10 cells was injected into each mouse through tail vein to develop the lung metastasis model. At 5, 7, and 9 days post tumor implantation (DPI5, DPI7 and DPI9), 50 μL of PBS containing free DOX or G4COOH–nDOX (1 mg of DOX/kg body weight per dose) was administered to each mouse via either pharyngeal aspiration (p.a. = lung delivery)33,34 or iv injection (via tail vein), which served as the control in terms of route of administration. The mice were deeply anesthetized with 2.5% v/v isoflurance/oxygen and then placed on a slant board in a supine position, and the nose was then gently pinched with tweezers. The tongue was gently extended, and 50 μL of sample-laden PBS was gradually dripped in the pharynx region with a Hamilton900 series syringe (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA). The tongue was returned after a few breaths. The mice were gently returned to the cage and monitored during a few minutes for recovery. The mice were observed daily for behavior (i.e., diet, drinking, and motion) and body weight. The mice were euthanized at DPI17 (=8 days after last dosing) or prior if necessary. The criteria for a terminal point before DPI17 include weight loss of 20% or more, obvious signs of illness in addition to the tumor, inability to move freely or significant quivering, and inability to eat/drink properly. The number of nodules in the lungs of each mouse were carefully counted (the lung metastases at late stages are characterized by large patches of nodules, so it is inappropriate/unlikely to count nodule number exactly at that phase). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were drawn by plotting survival rate as a function of DPI. The lungs of each mouse were also weighed out to evaluate tumor burden. These combined parameters are used to evaluate antitumor efficacy of free DOX and DOX-conjugated dendrimer conjugates. The cohorts with tumors but having only PBS administered iv or p.a. were used as positive controls. A total of 6 mice per cohort were employed for statistical analysis.

2.9. Systemic Distribution of DOX.

Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane/O2 (2.5% v/v). Blood was collected by cardiac puncture, and principal organs were then excised for quantifying systemic distribution of total DOX, free or in conjugate form. The lungs, heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, stomach, brain, thymus, axillary lymph nodes (ALN), brachial lymph nodes (BLN), cervical lymph nodes (CLN), and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) were excised. The tissues were homogenized in 3 mL of Triton X-100 (0.5% by weight) in PBS (0.5 M, pH 7.4) with a D1000 Hand-held Homogenizer (Thermo Scientific), and DOX was extracted into PBS at 37 °C for a period of 72 h in darkness. For liver, 5 mL of solution was needed instead. The homogenate was pelleted by centrifugation (22000g, 4 °C, 10 min), and 200 μL of the supernatant was taken to measure DOX fluorescence using Biotek Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (excitation/emission = 480 ± 20/595 ± 20 nm). The amount of DOX in each tissue was determined with respect to an established calibration curve, which was measured by spiking a predetermined amount of DOX into corresponding tissue. The determination was performed in triplicate. The same analysis was also performed in the PBS group (p.a. and iv), which served as controls.

2.10. Statistical Analysis.

GraphPad Prism 5 software was used for data analysis. The comparison between two systems was performed by Student’s t test, while that among multiple systems was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with either Dunnett’s test or Tukey’s post hoc test. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered to be statistically different, and the p-values were categorized as *p < 0.05, **p <0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Dendrimer–DOX Conjugates (G4COOH–nDOX).

PAMAM dendrimers have been widely used as drug delivery nanocarriers in cancer chemotherapy due to highly controlled size, low toxicity, nonimmunogenicity, and multiple functionalizable surface groups.24,35 Hydrazone bonds have been recognized as one of the most promising acid-labile spacers in covalently bonding DOX to polymer due to its high sensitivity to mild acidity (pH < ca. 5) and relatively straightforward chemistry.31,36 Hydrazone and its derivatives are relatively stable at neutral but undergo rapid hydrolysis at mildly acidic conditions of the lysosomes.37 In this study, DOX was conjugated to G4COOH via hydrazone bonds. G4COOH was first modified on the surface with Boc-protected hydrazide. The successful modification of –COOH groups was evidenced by two peak shifts of –NHNH2 in TBC: 7.83 ppm (–NH–) to 9.52 ppm (–NHBoc) and 3.89 ppm (–NH2) to 8.67 ppm (–NHCO– adjacent to G4COOH). The protective Boc groups were subsequently removed to give rise to hydrazide groups (–NHNH2), which was evidenced by the shift of the –NHCO– (adjacent to G4COOH) peak from 8.67 to 9.02 ppm and disappearance of the peak at 9.52 ppm.38,39 The resulting –NH2 groups of hydrazides were further reacted with carbonyl group of DOX, leading to the formation of the hydrazone bonds, which are cleavable at mild acidic conditions (pH ≤ 5; e.g., intracellular lysosomal pH), but stable at near neutral conditions (e.g., extracellular physiological pH). Detailed 1H NMR and MALDI spectra of dendrimer–DOX conjugates and important intermediates are shown in Figure S1. DOX payload and molecular weight of dendrimer conjugate are quantified and summarized in Table 1. Approximately 12 DOX molecules are attached to each dendrimer according to 1H NMR spectra, which was in agreement with MALDI results (see calculation in Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Molecular Weight (MW), Number of Conjugated Doxorubicin (DOX) (n), Hydrodynamic Diameter (HD), and Zeta Potential (ζ) of Generation 4, Carboxyl-Terminated PAMAM Dendrimer (G4COOH) Conjugatea

| DOX content (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| conjugates | MW | 1H NMR | MALDI | HD ± sd (nm) | ζ ± sd (mV) |

| G4COOH | 17104 | 0 | 0 | 4.7 ± 1.8 | −6.6 ± 4.1 |

| G4COOH-30Hyd | 17780 | 0 | 0 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | −0.5 ± 2.6 |

| G4COOH–12DOX | 23861 | 12.2 | 11.5 | 9.7 ± 3.5 | +13.8 ± 7.0 |

DOX was conjugated through an acid-labile hydrazone linker. Results obtained by 1H NMR, MALDI, and light scattering (LS) at 25 °C; sd = standard deviation.

Size, surface charge, and surface chemistry are some of the primary parameters to be considered in the design of drug delivery systems as they strongly affect the interaction with the physiological environment, including the biodistribution and PK of the conjugates.40,41 It can be seen that the hydrodynamic diameter (HD) of the dendrimer slightly decreased upon surface modification with hydrazides (4.7 to 3.6 nm), whereas an obvious increase is observed upon DOX conjugation (4.7 to9.7 nm). It is also observed that the ζ increased from a negative value of −6.6 ± 4.0 mV for bare G4COOH to a moderately high positive charge of +13.8 ± 7.0 mV upon DOX conjugation. The remaining hydrazides (ca. 18) on surface and primary amines of DOX (ca. 12) are protonated at physiological pH (7.2–7.4), which can offset the negative charges from the remaining terminal carboxyl groups. Therefore, the overall surface potential of dendrimer–DOX conjugate turns out to be positive, which may be beneficial in terms of enhancing cellular internalization in the pulmonary epithelia.41

3.2. Sustained In vitro Release of DOX from the Acid-Labile G4COOH–12DOX Conjugates.

The release of DOX from the dendrimer–DOX conjugates was determined at two pH values: mild acidic (i.e., lysosomal pH 5–4.5) and physiological (i.e., pH 7.4–7.2) conditions.31,42 The results are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

In vitro release profiles of DOX from acid-labile G4COOH–12DOX at lysosomal pH = 4.5 and physiological pH = 7.4, both at 37 °C. Results represent mean ± standard deviation (n = 3 per group). The diffusion of free DOX out of dialysis membrane (MWCO = 3000 Da) at both pH values is used as control.

As shown in Figure 2, the release of DOX from G4COOH was shown to be dependent on pH. A negligible (<4%) amount of DOX was released at pH 7.4, while in an acidic medium over 80% DOX was released from the conjugate at 48 h. In contrast, free DOX diffused out of dialysis membrane at a fairly rapid rate (over 90% release at approximately 7 h) for both pH values. Based on the release profile of free DOX, approximately ca. 7–10% of DOX cannot be recovered (7% at pH 7.4 and 9% at pH 4.5), likely due to interactions of DOX with the dialysis bag and photobleaching. Similar losses can be expected for the conjugates, indicating a recovery of over 86% from the “viable” DOX.

The acid-labile dendrimer–DOX conjugate demonstrates high stability at extracellular physiological pH, while a sustained DOX release at pH similar to that in acidic compartment. The high sensitivity of the dendrimer–DOX conjugates merely to acidic conditions is of great relevance as it can be expected to translate to a decrease in the concentration of free DOX in plasma by promoting intracellular release of DOX: spatial control. The decreased DOX concentration in plasma mitigates the acute and chronic cardiac toxicity of DOX, which is a major limitation in its long-term use, as well as its application in certain patient populations.43,44 In lung tumor chemotherapy, only a few percent of the total dose of DOX is known to reach tumor lesion upon systemic administration.9 The incidence of fatal myelosuppression (decreased bone marrow activity) and cardiomyopathy is significantly increased when the cumulative dose of DOX is over a certain limit (e.g., 400–550 mg/m2 of body surface area).45 Therefore, spatially controlled DOX release—intracellular release—has the potential to reduce the access of free DOX to systemic circulation and bone marrow.

3.3. Cell Kill of B16-F10 Melanoma Cells Lines by the G4COOH–12DOX Conjugates.

The cytotoxicity of free DOX and G4COOH–12DOX against B16-F10 cells was assessed by MTT assay. As shown in Figure 3, the dendrimer carrier (G4COOH-30Hyd) was not toxic against B16-F10 cells at concentrations below ca. 30 μM (cell viability: 91.5 ± 5.7%) after 48 h incubation. Its high IC50 (109.90 μM) may be ascribed to the neutral charge of hydrazide-modified dendrimer (see Table 1). The amines in hydrazide groups are neutralized by almost equivalent carboxyl groups on dendrimer surface, thus resulting in the apparent neutral surface charge. The G4COOH–12DOX conjugate (IC50 = 5.85 μM) was slightly less toxic (2.3-fold less potent) than free DOX against B16-F10 melanoma cells at 48 h incubation. It is noted that each dendrimer molecule carries ca. 12 drug molecules. When the concentration of DOX is 5.85 μM, the dendrimer is only 0.50 μM. Below 1 μM (G4COOH-30Hyd concentration), no toxicity is expected from dendrimer carrier, thus potentially indicating a strong safety profile for the chosen carrier. The difference in toxicity can be mainly ascribed to (i) the sustained release of conjugated DOX (see discussion in section 3.2), not all DOX is in free form at 48 h;14 (ii) differing extent of cellular uptake (see discussion in section 3.4); and (iii) differing subcellular trafficking pathways of free and conjugated DOX. Our recent work showed that, upon cellular internalization, DOX that is released from acid-labile dendrimer–DOX conjugates moves to the nuclei at a slower pace and also to a relatively lesser extent than free DOX: more than 80% intracellular DOX was colocalized with nuclei in free DOX group, while only 60–70% intracellular DOX was colocalized with nuclei in conjugated DOX group at 96 h.14 However, as incubation was extended to longer times (144 h: DOX-containing medium was removed after 72 h, and fresh medium was used for another 72 h), the cytotoxicity of dendrimer–DOX conjugate is similar to that of free DOX, indicating similar levels of nuclear targeting.14 Free DOX can directly diffuse through cellular membrane and reach the nucleus,46 while the trafficking of conjugated DOX to nucleus is more complex. That is, dendrimer-bound DOX is internalized through endocytic pathways, followed by DOX release from dendrimers upon the cleavage of hydrazone in acidic compartments.14 The diffusion of released DOX out of lysosome is a time-consuming process as the internal membrane of lysosomes is permeable to the base form DOX.47 Mild acidity in lysosomes protonates a substantial majority of DOX ([DOX + H]+), which then needs to be converted to free base for outflow. The forward conversion of cationic DOX to free base (both forms are at equilibrium) is driven by DOX efflux from lysosomes.47

Figure 3.

Cell kill of acid-labile G4COOH–12DOX as determined by MTT assay after 48 h incubation with B16-F10 melanoma cells. Free DOX and G4COOH-30Hyd are used as controls; note here that the figure inset represents concentration of dendrimer while the main figure represents concentration of DOX. Results represent mean ± standard deviation (n = 8 per group). IC50 was calculated on the basis of nonlinear regression Log(inhibitor) vs response (variable slope) with G4COOH-12Hyd being 109.90 μM (of dendrimer), G4COOH–12DOX being 5.85 μM (of DOX equivalent), and free DOX being 2.50 μM. Statistical analysis is calculated with respect to free DOX by Student’s test.

It is also important to note that the therapeutic efficacy in vivo depends on the ability of the payload to reach the tumor site first and foremost (before it can be internalized), and nanocarrier systems are expected to perform better than the free therapeutic.8,48 Therefore, while In vitro studies may show slightly less ability of the conjugated system to kill cancer cells, the expectation is that the nanocarrier conjugates will outperform the free drug in vivo.

3.4. Enhanced Cellular Internalization of DOX by Its Conjugation to Dendrimer Conjugate.

The cellular internalization of free DOX and G4COOH–12DOX conjugate by B16-F10 cells was investigated as a function of time by flow cytometry. The kinetics were evaluated by a plot of median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DOX internalized within the cells as a function of time, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Cellular internalization of the acid-labile G4COOH–12DOX in B16-F10 melanoma cells as a function of time, as determined by flow cytometry. Results denote mean ± standard deviation (n = 3 per group). Statistical significance is calculated with respect to free DOX by Student’s t test. The rates of internalization of G4COOH–12DOX (conjugated DOX) and free DOX are 268.7 AU h−1 (R2 = 0.963) and 35.7 AU h−1 (R2 = 0.981), respectively. The rate is calculated by linear fitting of 3 initial time points.

It is observed that the rate and extent of internalization of DOX were enhanced upon the conjugation to dendrimer nanocarriers. The conjugated DOX had an initial rate of internalization of 268.7 AU h−1, which was approximately 7.5-fold greater than that of free DOX (35.7 AU h−1). The overall extent of internalization of conjugated DOX was significantly different from that of free DOX, at least within the time frame of the experiment: 5 h. However, the difference narrowed down over time. The overall uptake of G4COOH–12DOX was 7.8, 4.1, and 2.5 times as high as that of free DOX at 0.5, 2, and 5 h incubation, respectively.

Earlier works show that DOX internalizes into cells by passive diffusion, and that the internalization is determined by the concentration gradient and hydrophobicity of DOX.46,49 Dendrimers are internalized via various endocytic pathways including macropinocytosis,50 receptor-mediated endocytosis,28,50,51 and nonspecific, adsorptive endocytosis.51–53 The preferred endocytic pathways are dictated by size, shape, and surface chemistry. The significantly enhanced rate and extent of internalization of G4COOH–12DOX by B16-F10 cells can be attributed at least in part to its positively charged surface upon DOX attachment. G4COOH–12DOX conjugate with a ζ of +13.8 mV is readily adsorbed on negative plasma membrane and quickly saturates the membrane,52 which results in rapid internalization and uptake plateau (found at 1.5–2 h incubation). The nonspecific, adsorptive endocytosis is faster and less energy-dependent than other endocytic pathways due to its electrostatic nature.28

The apparent paradox between weaker In vitro potency and enhanced uptake of the conjugates, which has been also observed for other polymer–DOX systems conjugated through acid-labile bonds,8,54 could be interpreted in the following way: (1) incubation time has a stronger effect on cell kill of acid-labile conjugates than free DOX due to sustained release from the conjugates. The ability of dendrimer–DOX conjugates to kill cancer cells In vitro is very close to that of free DOX as incubation is prolonged14 (MTT assay is conducted at 48 h compared to the uptake kinetics over 5 h discussed here); (2) to a lesser extent, dendrimers are likely to disrupt endosomes and lysosomes due to the protonation of tertiary amines as their concentration in acidic compartments increases.55 The disruption of acidic compartments lead to a failure to release DOX from dendrimer conjugates,8,31 resulting in an underestimation of cell kill of the dendrimer–DOX conjugate by MTT assay when the concentration of conjugate is relatively high; (3) dendrimer conjugates are internalized through various endocytic pathways, including those whose vesicles do not evolve into acidic compartments.56–58 For instance, caveolae-mediated endocytosis internalizes substances into nonacidic caveosomes,59 where DOX will have a lesser chance to be released from dendrimers.

In summary, the cellular uptake of DOX is significantly enhanced upon its conjugation to the dendrimer nanocarriers discussed here. This is relevant as greater intracellular concentration of DOX may be achieved while also minimizing plasma concentration, which in turn is expected to mitigate systemic adverse effects, especially to the cardiac tissue.

3.5. Effect of the G4COOH–12DOX Conjugates in Treating Lung Metastasis.

We investigated the impact of conjugation and route of delivery (p.a. and iv) on the efficacy of DOX in reducing the metastatic lung tumor burden. The pharyngeal aspiration (p.a.) technique is used for pulmonary delivery as it is less invasive (causes less trauma in the respiratory tract than compared to alternative routes),33 and yet can also efficiently deliver the payload to the lungs.33,60 Additionally, p.a. tends to result in a peripheral lung distribution of the delivered substances,60 while intratracheal instillation results in central lung distribution.60,61 As shown in Figure 5, the development of numerous black nodules in the lungs showed that neither free nor conjugated DOX suppressed the proliferation of lung tumors when administered iv; note, however, that the intensity of tumor nodules appears to be slightly less in the case of G4COOH–12DOX compared to the free DOX group. Because the density of nodules is so high, it is hard to clearly count them, and thus only a qualitative assessment can be achieved by visually inspecting the lung tissue upon iv treatment.

Figure 5.

Images of lungs collected from C57BL/6 mice bearing lung metastases (n = 6 per group). PBS, free DOX, or G4COOH–12DOX is administered through the iv or p.a. route; iv = intravenous injection; p.a. = pharyngeal aspiration (pulmonary route). The lungs excised from nondisease mice are used as negative control (top row). “+” in “Mets” column denotes mice bearing lung tumors from metastatic melanoma, and negative control represents the mice without lung metastases and no treatment.

In contrast, only a small number of lung nodules were observed in the treatment groups where DOX was administered via pulmonary route, revealing that either free or conjugated DOX delivered directly to the lungs significantly inhibits the growth of metastatic tumor in the lungs, and it is thus a superior route of administration when compared to iv. Additionally, the number of lung nodules in the G4COOH–12DOX p.a. group was significantly smaller than that of the free DOX p.a. group (6.8 ± 0.5 versus 10.3 ± 1.0; p = 0.0063), demonstrating that conjugation further enhances treatment efficacy. A significant reduction in the number of lung nodules has been also reported in previous work in which lung metastasis bearing mice were treated with PEI–DOX21 and PEGylated PLL–DOX conjugates.20 While those represent different polymers and disease models, they serve as benchmarks to our work.

While the counting of lung nodules can be employed to qualitatively evaluate tumor burden, it is somewhat limited as it is difficult to delineate single nodules, especially when nodules are numerous and are of different sizes, and to spot deeper lung tumors such as intralobular nodules. Therefore, other methods should be employed to further assess the effectiveness of therapeutics in reducing tumor burden. We selected the overall weight of lungs as a complementary parameter to nodule counts. The results are summarized in Figure 6 as a function of delivery route and conjugation. The lung weights of two positive control groups—PBS iv (213 ± 24 mg, p = 0.0098) and PBS p.a. (201 ± 30 mg, p = 0.0177)—were significantly greater than those of healthy mice (142 ± 11 mg). Among all treatment groups, neither DOX iv nor G4COOH–12DOX iv significantly altered overall lung weights (DOX, 202 ± 22 mg, and G4COOH–12DOX, 195 ± 26 mg) compared to their positive group (PBS iv). In contrast, the tumor-bearing mice treated with either DOX p.a. (159 ± 18 mg, p = 0.0336) or G4COOH–12DOX p.a. (152 ± 15 mg, p = 0.0259) had significantly reduced lung weights compared to positive group (PBS p.a.). We also observed that the groups treated with the same therapeutics but via different routes showed significant difference in lung tumor burden. That is, DOX group, iv:p.a. = (202 ± 22 mg):(159 ± 18 mg) (p = 0.0415); and G4COOH–12DOX group, iv:p.a. = (194 ± 26 mg):(152 ± 14 mg) (p = 0.0489). It is noted that the three widely recognized methods in the literature19,21,62,63 (i.e., the images of representative lungs, nodule counts, and lung weights) are all qualitative assessments in terms of lung tumor burden, but they are consistent among the groups and can thus be used to assess treatment efficacy.

Figure 6.

Weight of lungs excised from healthy C57BL/6 mice (negative control group; n = 3 per group) and tumor metastasis bearing mice treated with different therapies (n = 6 per group) at 17 days post implantation (DPI17). DPI17 (= 8 days after last dosing. Results represent mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis is performed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test; p.a. = pharyngeal aspiration; iv = intravenous injection; NC = negative control.

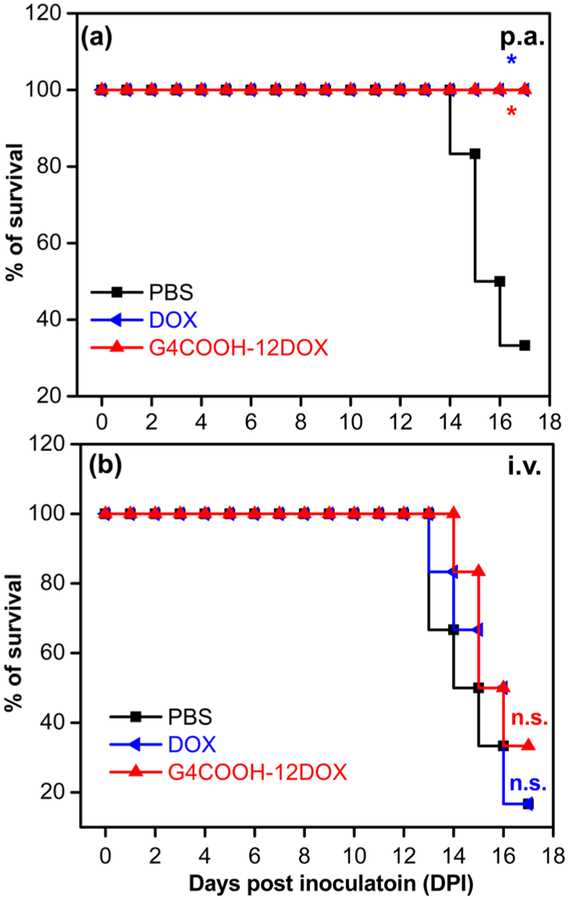

Significant body weight loss (>20%) and abnormal daily behavior of mice are key criteria to determine end point of experiment. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Figure 7) showed that 100% of mice treated with either DOX p.a. or G4COOH–12DOX p.a. were alive and exhibited no significant weight loss or obvious abnormal behavior at the terminal point, which represents a significant improvement in treatment (p =0.0185 for both groups) compared to the no treatment group (PBS p.a.), with only two mice alive (33.3% survival rate) at the terminal point. Three out of six mice showed over 20% weight loss and four mice showed obvious quivering and difficulty in motion before terminal point. In contrast, the treatments via the iv route were ineffective: neither DOX iv (survival rate,16.7%; >20% weight loss, 4/6 mice; quivering/motional problem, 5/6 mice) nor G4COOH–12DOX iv group (survival rate, 33.3%; >20% weight loss, 3/6 mice; quivering/motional problem, 4/6 mice) showed significant difference with respect to their positive control group (PBS iv: survival rate, 16.7%; >20% weight loss, 5/6 mice; quivering/motional problem, 5/6 mice).

Figure 7.

Survival rate of mice bearing lung metastases over 17 days, as plotted on a Kaplan–Meier survival curve. The survival rate of each group is analyzed using Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (*p < 0.05) with respect to the positive control of the same administration route (PBS); n.s. = not significant.

Lung metastasis inhibition is a key factor in chemotherapy. However, the potential lung toxicity associated with pulmonary delivery of DOX cannot be overlooked.20 The change in body weight of the mice is informative in the assessment of systemic and local toxicity. As shown in Figure S2a, there is no obvious decrease in the body weight of mice in group treated with DOX p.a. over the observation period. Furthermore, the body weight of the mouse group slightly increased as a function of DPI as DOX is conjugated to dendrimer. The unchanged body weights indicate the low/no lung toxicity associated with locally delivered DOX solution and conjugated DOX formulations. This may be due to the relatively low dose used in this work, which was yet very effective as discussed earlier.

In summary, the results discussed above show that lung metastatic tumors can be significantly inhibited by pulmonary delivered DOX, thus leading to an improved survival rate. The results also show that metastatic lung tumor burden is further relieved upon conjugation of DOX to dendrimer nanocarriers.

3.6. Impact of Administration Route and DOX Conjugation on Systemic Biodistribution.

Our In vitro results show that conjugation of DOX to dendrimer nanocarriers enhances the cellular uptake of DOX, while promoting intracellular release, demonstrating the potential to reduce systemic toxicity of DOX. However, the in vivo fate and distribution of DOX (free or in conjugate form) are much more complex as they are impacted by several factors, including various in vivo barriers which vary in different routes of administration. Therefore, we investigated the distribution of systemically and locally (lung) delivered DOX (free or in conjugate form) in major organs. The systemic distribution results are summarized in Figure S3 and Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Systemic distribution of DOX and G4COOH–12DOX delivered via (a) p.a. and (b) iv. Mice bearing lung metastases were euthanized at 17 days post implantation (DPI17) or terminal point prior to DPI17 (= 8 days after last dosing). Results represent mean ± standard deviation (n = 6 per group). The groups of same administration (p.a. or iv) are analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. % of TD = % of total dosage; p.a. = pharyngeal aspiration; iv = intravenous injection.

The results show that the DOX tissue distribution is strongly impacted by the route of administration and conjugation. As shown in Figure S3, the amount of DOX in the lungs at DPI17 (8 days after last dosing) followed the sequence G4COOH–12DOX p.a. (26.8 ± 5.0% of total dose (TD)) > DOX p.a. (9.8 ± 4.3% of TD) ≫ G4COOH–12DOX iv (1.1 ± 0.4% of TD) ≈ DOX iv (0.5 ± 0.1% of TD). The fact that DOX in conjugate form is resident in the lungs at a greater concentration after dosing suggests that, upon further optimization of dosages (concentration and number), there is the potential to decrease either total dosage or the number of dosages. For comparison, it is worth noting that previous studies have shown that a large amount of DOX-loaded PLGA nanoparticles remained in the lungs 1 week after inhalation, and a detectable amount of DOX was still found up to 14 days post treatment.19 Similarly, PEI-conjugated DOX could be still clearly seen 7 days after i.t. administration.21 Pulmonary delivered PEGylated dendritic PLL with similar hydrodynamic diameter (9.9 nm) was also able to achieve long retention in the lungs of normal rat model (ca. 40% of total dose 7 days after administration).64 One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test showed that the amount of DOX in the lungs of G4COOH–12DOX p.a. group was significantly greater with respect to that of all other groups: DOX p.a. group (p = 0.0194), G4COOH–12DOX iv (p < 0.001), and DOX iv (p < 0.001). Additionally, the amount of DOX in the lungs of DOX p.a. group was also much greater than that of G4COOH–12DOX iv (p = 0.0038) and DOX iv group (p =0.0050). However, no statistical difference was found between DOX iv and G4COOH–12DOX iv group.

Our recent results demonstrate that the fate of PAMAM dendrimer nanocarriers administered to the lungs is greatly impacted by their surface charge: positively charged PAMAM dendrimers tend to reside locally (lungs) for longer, while neutral dendrimers tend to more effectively translocate into systemic circulation.25 The HD of G4COOH–12DOX is ca. 10 nm, which is larger than the fenestration of the endothelial lining of vascular vessels (4–5 nm).65 Compared to small molecule drugs, reverse diffusion of dendrimer conjugates into vascular vessels for clearance is thus reduced.65 In the meantime, the drainage of dendrimer conjugates from interstitial fluid/space through the lymphatic system is also much attenuated in tumor tissues due to a lack of effective lymphatic drainage (enhanced permeability and retention effect in solid tumors).48,66 These conditions thus likely lead to a preferred retention of dendrimer-bound DOX in the lungs compared to free DOX.

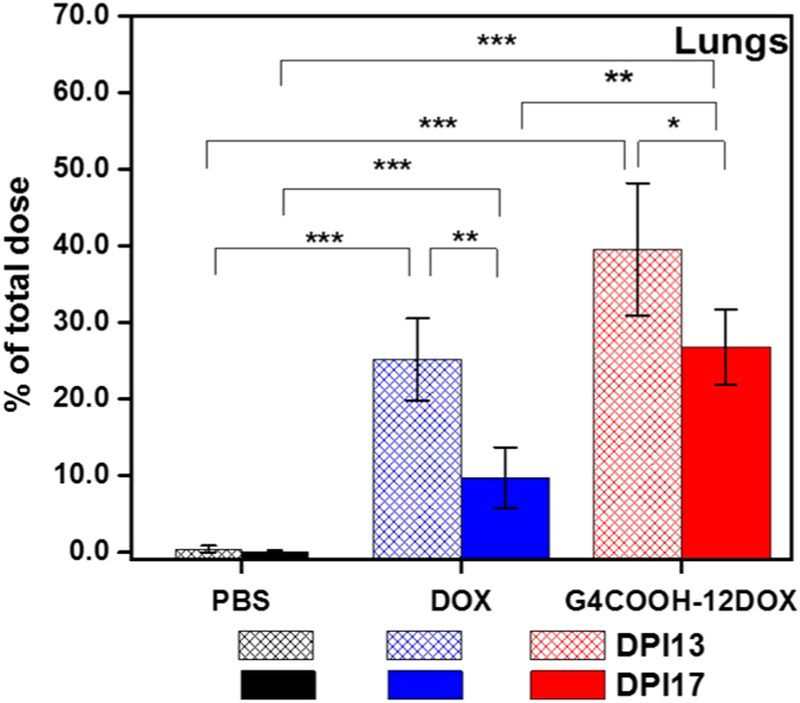

Due to the enhanced local concentration of drug upon pulmonary administration, we investigated the temporal effect on pulmonary retention of locally delivered DOX and G4COOH–12DOX. We compared the content of DOX in the lungs at DPI13 (4 days after last dosing) and DPI17 (8 days after last dosing). The results are summarized in Figure 9. At DPI13, the amount of DOX in the lungs was 39.1 ± 8.5% of total dose (TD) for G4COOH–12DOX p.a. and 25.2 ± 5.3% of TD for free DOX p.a. (p = 0.0765 with respect to G4COOH–12DOX p.a. at DPI13). At DPI17, the % of TD decreased for both free and conjugated DOX. However, the elimination of free DOX from the lung tissue was much more substantial, decreasing at almost twice the rate when compared to conjugated DOX, being at 26.8 ± 5.0% of TD for G4COOH–12DOX p.a. and 9.8 ± 4.0% TD for free DOX p.a. (p = 0.0089 with respect to G4COOH–12DOX p.a.) at DPI17. Therefore, a higher DOX retention and a much greater p value at DPI13 demonstrates that conjugation to the dendrimer nanocarriers slows down the elimination of DOX from the lungs. The processes responsible for dendrimer–DOX and DOX clearance in the lungs may include mucociliary escalator, pulmonary alveolar macrophage phagocytosis, translocation to systemic circulation, and draining to lymphatics.67–70

Figure 9.

Temporal effect on accumulation of DOX (free/conjugated form) in the lungs. Therapeutics were given through pharyngeal aspiration. The mice were euthanized at DPI13 (n = 3 per group; DPI13 = 4 days after last dosing) and DPI17 (n = 6 per group; DPI17 = 8 days after last dosing). Statistical analysis is performed in 2 different ways: (i) all groups at DPI13 or DPI17 are analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; (ii) the same therapy groups (e.g., DOX p.a.) at DPI13 and DPI17 are analyzed with Student’s t test. Results represent mean ± standard deviation; DPI = days post implantation.

Interestingly, the groups treated with either DOX p.a. or G4COOH–12DOX p.a. showed lower cardiac accumulation of DOX compared to the distribution upon iv administration as can be seen in Figure S4 and Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Temporal effect on accumulation of DOX (free/conjugated form) in the heart. Therapeutics were administered through pharyngeal aspiration. The mice were euthanized at DPI13 (n = 3 per group; DPI13 = 4 days after last dosing) and DPI17 (n = 6 per group; DPI17 = 8 days after last dosing). Statistical analysis is performed exactly as in Figure 9. DPI = days post implantation.

No statistical difference was found between the two p.a. groups. It was also noticeable that intravenous injection of free DOX was the system that resulted in the greatest accumulation of DOX in the cardiac tissue at terminal point compared to all other groups: Figure S4. Considering the limited accumulation of DOX in heart upon pulmonary administration, the cardiac content of locally delivered DOX as a function of time (sampled at DPI13 and DPI17) was further investigated. As shown in Figure 10, we observed that, at DPI13 (= 4 days after last dosing), the cardiac content of DOX in the groups (p.a.) treated with either DOX or G4COOH–12DOX was statistically greater than that of the no treatment group, whereas they decreased slightly at DPI17 (= 8 days after last dosing) and only the DOX p.a. group showed significant difference with respect to the no treatment group at that terminal point. Comparing with the iv injection route, however, the cardiac accumulation of DOX (even in the DOX p.a. group) was still much less at DPI17.

The results show that the distribution of DOX to the heart tissue can be mitigated upon pulmonary delivery, and further upon conjugation to dendrimers. This is of great relevance as major adverse effects, including lethal cardiomyopathy, are known to limit the applicability of DOX in the treatment of a variety of cancers including lung metastasis.71 It is also worth noting that the sum of the DOX concentration in the cardiac tissue delivered both iv and p.a., when conjugated, is less than that seen for free DOX delivered iv, thus indicating the potential of the combined iv and p.a. administration of the conjugate which may be useful in terms of overall treatment of patients with both lung and systemic metastases. When cancers metastasize, one cannot predict whether the tumor has metastasized to the lung tissue alone or other tissues as well; usually the latter is commonly observed. For example, lung, bone, and brain are major metastatic organs for breast and prostate cancers.72 Therefore, systemic administration of chemotherapeutics may be necessary from a clinical perspective, even if at that time only lung metastasis has been detected. However, one cannot as effectively treat lung metastasis with DOX systemically due to the poor distribution of DOX to the lungs. The combination of iv and pulmonary administered DOX or dendrimer–DOX conjugate is, therefore, of potential relevance as they may accomplish the inhibition of both systemic metastasis and organ-specific metastasis (i.e., lung metastasis), and at the same time reduce cardiac toxicity compared to iv administration alone.

Besides the ability to modulate the distribution of DOX in the lungs and heart, the results shown here demonstrate that the route of elimination of DOX is also impacted by the choice of delivery route and conjugation. As shown in Figure 8a,b, higher concentration/percentage dosage of DOX was found in spleen and liver upon conjugation to dendrimers independent of routes of administration. The clearance of polymeric delivery systems from plasma is dictated mainly by surface charge and particle size.41 Positively charged nanocarriers (i.e., G4COOH–12DOX in our case) can be cleared and processed by mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), whose targets are opsonized by plasma proteins and subsequently captured by phagocytes.73,74 Phagocytes, such as macrophages, mainly reside in or migrate to bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver, and spleen.75 It is also reported that dendrimer nanocarriers are cleared by glomerular filtration in kidneys.76 In this work, small amounts of DOX in the case of G4COOH–12DOX conjugate (iv, 0.84 ± 0.37% of TD; and p.a., 0.60 ± 0.29% of TD) were found in kidneys at DPI17 (8 days after last dosing). This may be to some extent due to the fact that the time for observing renal accumulation of DOX is too long. Previous research has shown that PAMAM dendrimers can be detected in urine 2 h after iv injection.77 On the other hand, it is also possible that the renal pathway may not play a vital role in clearing these dendrimer–DOX conjugates. Renal glomeruli have round pores of approximately 6 nm diameter. Therefore, the nanocarriers with diameter <6 nm are rapidly to be cleared by glomerular filtration. The hydrodynamic diameter of G4COOH–12DOX (9.7 ± 3.5 nm) is greater than the size threshold for glomerular filtration.41,74 Additionally, nanocarrier-biomolecule coronas are instantaneously formed when nanocarriers are exposed to physiological fluids, since plasma proteins are readily adsorbed on positively charged nanocarriers,78,79 leading to much greater physiological diameters than as light scattering measured.74

4. CONCLUSION

In this work, we show that pulmonary administration of DOX combined with conjugation to G4COOH through a pH sensitive bond is a potential strategy to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of DOX in the treatment of an in vivo model of lung metastasis established by injecting mouse melanoma B16-F10 cells in the tail vain of male C57BL/6 mice. The results show that the tumor burden is significantly decreased upon pulmonary administration and further decreased upon conjugation. Pulmonary administration of DOX (free and conjugated forms) also significantly improved the survival rate of diseased animals, which had a significantly higher percentage of the therapeutic dose residing in the lungs at the terminal point compared to the iv treatment groups. Biodistribution in the lung tissue further improved upon conjugation of DOX to dendrimer when delivered directly into the lungs with 27% of the drug residing in the lungs at the terminal point when conjugated, compared to only 10% of the free DOX. At the same time, the accumulation of DOX in the heart tissue significantly decreased upon conjugation and lung delivery (no statistical difference compared to negative control), indicating that this combination may result in not only enhanced therapeutic efficacy as shown here but also a potential decrease in systemic toxicity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF-CBET Grant No. 0933144; NSF-DMR Grant No. 1508363) and the NanoIncubator at WSU. We would also like to thank Microscopy, Imaging and Cytometry Resources Core (MICR) for help with the confocal microscopy. The MICR is supported, in part, by NIH Center Grant P30CA022453 to the Karmanos Cancer Institute and the Perinatology Research Branch of the National Institutes of Child Health and Development, both at WSU.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- PAMAM

poly(amidoamine)

- G4COOH

generation 4 carboxyl-terminated PAMAM dendrimer

- DOX

doxorubicin

- G4COOH–12DOX

G4COOH dendrimer with 12 DOX conjugated onto the surface

- NMM

N-methylmorpholine

- IBCF

isobutyl chloroformate

- TFA

trifluoroaetic acid

- DCM

dichloromethane

- TEA

triethylamine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DMSO-d6

deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- 2,5-DHB

2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid

- MWCO

molecular weight cutoff

- DI water

deionized water

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- Pen-Strep

penicillin–streptomycin

- HBSS

Hanks balanced salt solution

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- 1H NMR

proton nuclear magnetic resonance

- MALDI-TOF

mass-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight

- LS

light scattering

- MW

molecular weight

- HD

hydrodynamic diameter

- MFI

median fluorescence intensity

- iv

intravenous injection

- p.a.

pharyngeal aspiration

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- TD

total dose

- sd

standard deviation

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00126.

Characterization of G4COOH–12DOX, mouse body weights vs DPI, and accumulations of DOX in lungs and heart tissue (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Kochanek KD; Murphy SL; Xu J; Arias E Mortality in the United States, 2013; Centers for Disease Control and Prevetion: 2014; p 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Siegel R; Naishadham D; Jemal A Cancer statistics, 2013. Ca-Cancer J. Clin 2013, 63 (1), 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Wada H; Hitomi S; Teramatsu T Adjuvant chemotherapy after complete resection in non-small-cell lung cancer. West Japan Study Group for Lung Cancer Surgery. J. Clin. Oncol 1996, 14 (4), 1048–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Albain KS; Swann RS; Rusch VW; Turrisi AT; Shepherd FA; Smith C; Chen Y; Livingston RB; Feins RH; Gandara DR Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009, 374 (9687), 379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gupta GP; Massagué J Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell 2006, 127 (4), 679–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Nguyen DX; Bos PD; Massagué J Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9(4), 274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Garbuzenko OB; Saad M; Pozharov VP; Reuhl KR; Mainelis G; Minko T Inhibition of lung tumor growth by complex pulmonary delivery of drugs with oligonucleotides as suppressors of cellular resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107 (23), 10737–10742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zhu S; Hong M; Tang G; Qian L; Lin J; Jiang Y; Pei Y Partly PEGylated polyamidoamine dendrimer for tumor-selective targeting of doxorubicin: the effects of PEGylation degree and drug conjugation style. Biomaterials 2010, 31 (6), 1360–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cheng C; Haouala A; Krueger T; Mithieux F; Perentes JY; Peters S; Decosterd LA; Ris H-B Drug uptake in a rodent sarcoma model after intravenous injection or isolated lung perfusion of free/liposomal doxorubicin. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg 2009, 8(6), 635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Broxterman HJ; Versantvoort CH; Linn SC Multidrug resistance in lung cancer In Lung Cancer; Springer: 1995; pp 193–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Blum RH; Carter SK Adriamycin: a new anticancer drug with significant clinical activity. Ann. Intern. Med 1974, 80 (2), 249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Koukourakis M; Koukouraki S; Giatromanolaki A; Archimandritis S; Skarlatos J; Beroukas K; Bizakis J; Retalis G; Karkavitsas N; Helidonis E Liposomal doxorubicin and conventionally fractionated radiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer and head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 1999, 17 (11), 3512–3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Otterson GA; Villalona-Calero MA; Hicks W; Pan X; Ellerton JA; Gettinger SN; Murren JR Phase I/II Study of inhaled doxorubicin combined with platinum-based therapy for advanced non–small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 2010, 16 (8), 2466–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zhong Q; da Rocha SRP Poly(amidoamine) dendrimer–doxorubicin conjugates: In vitro characteristics and pseudosolution formulation in pressurized metered-dose inhalers. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2016, 13 (3), 1058–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Thorn CF; Oshiro C; Marsh S; Hernandez-Boussard T; McLeod H; Klein TE; Altman RB Doxorubicin pathways: pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 2011, 21 (7), 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hagane K; Akera T; Berlin J Doxorubicin: mechanism of cardiodepressant actions in guinea pigs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1988, 246 (2), 655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chatterjee K; Zhang J; Honbo N; Karliner JS Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 2010, 115 (2), 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Roa WH; Azarmi S; Al-Hallak MK; Finlay WH; Magliocco AM; Löbenberg R Inhalable nanoparticles, a noninvasive approach to treat lung cancer in a mouse model. J. Controlled Release 2011, 150 (1), 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kim I; Byeon HJ; Kim TH; Lee ES; Oh KT; Shin BS; Lee KC; Youn YS Doxorubicin-loaded highly porous large PLGA microparticles as a sustained-release inhalation system for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer. Biomaterials 2012, 33 (22), 5574–5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kaminskas LM; McLeod VM; Ryan GM; Kelly BD; Haynes JM; Williamson M; Thienthong N; Owen DJ; Porter CJ Pulmonary administration of a doxorubicin-conjugated dendrimer enhances drug exposure to lung metastases and improves cancer therapy. J. Controlled Release 2014, 183, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Xu C; Wang P; Zhang J; Tian H; Park K; Chen X Pulmonary codelivery of doxorubicin and siRNA by pH-sensitive nanoparticles for therapy of metastatic lung cancer. Small 2015, 11(34), 4321–4333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Menjoge AR; Kannan RM; Tomalia DA Dendrimer-based drug and imaging conjugates: design considerations for nanomedical applications. Drug Discovery Today 2010, 15 (5), 171–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tomalia DA; Naylor AM; Goddard WA Starburst dendrimers: molecular-level control of size, shape, surface chemistry, topology, and flexibility from atoms to macroscopic matter. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1990, 29 (2), 138–175. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Duncan R; Izzo L Dendrimer biocompatibility and toxicity. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2005, 57 (15), 2215–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bharatwaj B; Mohammad AK; Dimovski R; Cassio FL; Bazito RC; Conti D; Fu Q; Reineke J; da Rocha SR Dendrimer nanocarriers for transport modulation across models of the pulmonary epithelium. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, 12 (3), 826–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zhong Q; Merkel OM; Reineke JJ; da Rocha SRP Effect of the Route of Administration and PEGylation of Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers on Their Systemic and Lung Cellular Biodistribution. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2016, 13, 1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bielski ER; Zhong Q; Brown M; da Rocha SRP Effect of the Conjugation Density of Triphenylphosphonium Cation on the Mitochondrial Targeting of Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, 12 (8), 3043–3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kitchens KM; Foraker AB; Kolhatkar RB; Swaan PW; Ghandehari H Endocytosis and interaction of poly (amidoamine) dendrimers with Caco-2 cells. Pharm. Res 2007, 24 (11), 2138–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dobrovolskaia MA; Patri AK; Simak J; Hall JB; Semberova J; De Paoli Lacerda SH; McNeil SE Nanoparticle size and surface charge determine effects of PAMAM dendrimers on human platelets In vitro. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9 (3), 382–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cheng Y; Xu T The effect of dendrimers on the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic behaviors of non-covalently or covalently attached drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2008, 43 (11), 2291–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lai P-S; Lou P-J; Peng C-L; Pai C-L; Yen W-N; Huang M-Y; Young T-H; Shieh M-J Doxorubicin delivery by polyamidoamine dendrimer conjugation and photochemical internalization for cancer therapy. J. Controlled Release 2007, 122 (1), 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ganta S; Devalapally H; Shahiwala A; Amiji M A review of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. J. Controlled Release 2008, 126 (3), 187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Rao G; Tinkle S; Weissman D; Antonini J; Kashon M; Salmen R; Battelli L; Willard P; Hubbs A; Hoover M Efficacy of a technique for exposing the mouse lung to particles aspirated from the pharynx. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A 2003, 66 (15–16), 1441–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mohammad AK; Amayreh LK; Mazzara JM; Reineke JJ Rapid lymph accumulation of polystyrene nanoparticles following pulmonary administration. Pharm. Res 2013, 30 (2), 424–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Medina SH; El-Sayed ME Dendrimers as carriers for delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Chem. Rev 2009, 109 (7), 3141–3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Etrych T; Jelínková M; Říhová B; Ulbrich K New HPMA copolymers containing doxorubicin bound via pH-sensitive linkage: synthesis and preliminary In vitro and in vivo biological properties. J. Controlled Release 2001, 73 (1), 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wu AM; Senter PD Arming antibodies: prospects and challenges for immunoconjugates. Nat. Biotechnol 2005, 23 (9), 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lu C; Zhong W Synthesis of propargyl-terminated heterobifunctional poly (ethylene glycol). Polymers 2010, 2 (4), 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- (39).King HD; Yurgaitis D; Willner D; Firestone RA; Yang MB; Lasch SJ; Hellström KE; Trail PA Monoclonal antibody conjugates of doxorubicin prepared with branched linkers: A novel method for increasing the potency of doxorubicin immunoconjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999, 10 (2), 279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kaminskas LM; Boyd BJ; Porter CJ Dendrimer pharmacokinetics: the effect of size, structure and surface characteristics on ADME properties. Nanomedicine 2011, 6 (6), 1063–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Albanese A; Tang PS; Chan WC The effect of nanoparticle size, shape, and surface chemistry on biological systems. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2012, 14, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Rıhová B; Etrych T; Pechar M; Jelınková M; Štastný M; Hovorka O; Kovář M; Ulbrich K Doxorubicin bound to a HPMA copolymer carrier through hydrazone bond is effective also in a cancer cell line with a limited content of lysosomes. J. Controlled Release 2001, 74 (1), 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Tokudome T; Mizushige K; Noma T; Manabe K; Murakami K; Tsuji T; Nozaki S; Tomohiro A; Matsuo H Prevention of doxorubicin (adriamycin)-induced cardiomyopathy by simultaneous administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor assessed by acoustic densitometry. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol 2000, 36 (3), 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Cardinale D; Colombo A; Sandri MT; Lamantia G; Colombo N; Civelli M; Martinelli G; Veglia F; Fiorentini C; Cipolla CM Prevention of high-dose chemotherapy–induced cardiotoxicity in high-risk patients by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Circulation 2006, 114 (23), 2474–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Vejpongsa P; Yeh ET Prevention of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: challenges and opportunities. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2014, 64 (9), 938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Speelmans G; Staffhorst RW; de Kruijff B; de Wolf FA Transport studies of doxorubicin in model membranes indicate a difference in passive diffusion across and binding at the outer and inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. Biochemistry 1994, 33 (46), 13761–13768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).De Duve C; De Barsy T; Poole B; Trouet A; Tulkens P; Van Hoof F Lysosomotropic agents. Biochem. Pharmacol 1974, 23(18), 2495–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Malik N; Evagorou EG; Duncan R Dendrimer-platinate: a novel approach to cancer chemotherapy. Anti-Cancer Drugs 1999, 10(8), 767–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Frezard F; Garnier-Suillerot A DNA-containing liposomes as a model for the study of cell membrane permeation by anthracycline derivatives. Biochemistry 1991, 30 (20), 5038–5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Albertazzi L; Serresi M; Albanese A; Beltram F Dendrimer internalization and intracellular trafficking in living cells. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2010, 7 (3), 680–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Kitchens KM; Kolhatkar RB; Swaan PW; Ghandehari H Endocytosis inhibitors prevent poly (amidoamine) dendrimer internalization and permeability across Caco-2 cells. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2008, 5 (2), 364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Seib FP; Jones AT; Duncan R Comparison of the endocytic properties of linear and branched PEIs, and cationic PAMAM dendrimers in B16f10 melanoma cells. J. Controlled Release 2007, 117 (3), 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Sahay G; Alakhova DY; Kabanov AV Endocytosis of nanomedicines. J. Controlled Release 2010, 145 (3), 182–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Minko T; Kopečková P; Pozharov V; Kopecek J HPMA copolymer bound adriamycin overcomes MDR1 gene encoded resistance in a human ovarian carcinoma cell line. J. Controlled Release 1998, 54 (2), 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Dufes C; Uchegbu IF; Schätzlein AG Dendrimers in gene delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2005, 57 (15), 2177–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hillaireau H; Couvreur P Nanocarriers’ entry into the cell: relevance to drug delivery. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66 (17), 2873–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Perumal OP; Inapagolla R; Kannan S; Kannan RM The effect of surface functionality on cellular trafficking of dendrimers. Biomaterials 2008, 29 (24), 3469–3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Goldberg DS; Ghandehari H; Swaan PW Cellular entry of G3. 5 poly (amido amine) dendrimers by clathrin-and dynamin-dependent endocytosis promotes tight junctional opening in intestinal epithelia. Pharm. Res 2010, 27 (8), 1547–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Alfonso A; Payne GS; Donaldson J; Segev N Trafficking Inside Cells: Pathways, Mechanisms and Regulation; Springer Science & Business Media: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lakatos HF; Burgess HA; Thatcher TH; Redonnet MR; Hernady E; Williams JP; Sime PJ Oropharyngeal aspiration of a silica suspension produces a superior model of silicosis in the mouse when compared to intratracheal instillation. Exp. Lung Res 2006, 32(5), 181–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Driscoll KE; Costa DL; Hatch G; Henderson R; Oberdorster G; Salem H; Schlesinger RB Intratracheal instillation as an exposure technique for the evaluation of respiratory tract toxicity: uses and limitations. Toxicol. Sci 2000, 55 (1), 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Xu Z; Ramishetti S; Tseng Y-C; Guo S; Wang Y; Huang L Multifunctional nanoparticles co-delivering Trp2 peptide and CpG adjuvant induce potent cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response against melanoma and its lung metastasis. J. Controlled Release 2013, 172 (1), 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Hu Y-L; Huang B; Zhang T-Y; Miao P-H; Tang G-P; Tabata Y; Gao J-Q Mesenchymal stem cells as a novel carrier for targeted delivery of gene in cancer therapy based on nonviral transfection. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9 (9), 2698–2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Ryan GM; Kaminskas LM; Kelly BD; Owen DJ; McIntosh MP; Porter CJ Pulmonary administration of PEGylated polylysine dendrimers: absorption from the lung versus retention within the lung is highly size-dependent. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10(8), 2986–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Liu H; Irvine DJ Guiding principles in the design of molecular bioconjugates for vaccine applications. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Prabhakar U; Maeda H; Jain RK; Sevick-Muraca EM; Zamboni W; Farokhzad OC; Barry ST; Gabizon A; Grodzinski P; Blakey DC Challenges and key considerations of the enhanced permeability and retention effect for nanomedicine drug delivery in oncology. Cancer Res. 2013, 73 (8), 2412–2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Semmler-Behnke M; Takenaka S; Fertsch S; Wenk A; Seitz J; Mayer P; Oberdörster G; Kreyling WG Efficient elimination of inhaled nanoparticles from the alveolar region: evidence for interstitial uptake and subsequent reentrainment onto airways epithelium. Environ. Health Perspect 2007, 115, 728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Harmsen AG; Muggenburg BA; Snipes MB; Bice DE The role of macrophages in particle translocation from lungs to lymph nodes. Science 1985, 230 (4731), 1277–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Lai SK; Wang Y-Y; Hanes J Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2009, 61 (2), 158–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Choi HS; Ashitate Y; Lee JH; Kim SH; Matsui A; Insin N; Bawendi MG; Semmler-Behnke M; Frangioni JV; Tsuda A Rapid translocation of nanoparticles from the lung airspaces to the body. Nat. Biotechnol 2010, 28 (12), 1300–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Singal PK; Iliskovic N Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy.N. Engl. J. Med 1998, 339 (13), 900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Chambers AF; Groom AC; MacDonald IC Metastasis: dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2 (8), 563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Xiao K; Li Y; Luo J; Lee JS; Xiao W; Gonik AM; Agarwal R; Lam KS The effect of surface charge on in vivo biodistribution of PEG-oligocholic acid based micellar nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (13), 3435–3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Kobayashi H; Watanabe R; Choyke PL Improving conventional enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) Effects; what is the appropriate target? Theranostics 2014, 4 (1), 81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Owens DE III; Peppas NA Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm 2006, 307 (1), 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Venditto VJ; Regino CAS; Brechbiel MW PAMAM dendrimer based macromolecules as improved contrast agents. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2005, 2 (4), 302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Nigavekar SS; Sung LY; Llanes M; El-Jawahri A; Lawrence TS; Becker CW; Balogh L; Khan MK 3H dendrimer nanoparticle organ/tumor distribution. Pharm. Res 2004, 21 (3), 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Pearson RM; Juettner VV; Hong S Biomolecular corona on nanoparticles: a survey of recent literature and its implications in targeted drug delivery. Front. Chem 2014, DOI: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Åkesson A; Cárdenas M; Elia G; Monopoli MP; Dawson KA The protein corona of dendrimers: PAMAM binds and activates complement proteins in human plasma in a generation dependent manner. RSC Adv. 2012, 2 (30), 11245–11248. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.