Abstract

Background:

Although it has been suggested that individuals of low socioeconomic status and those with Medicaid or no insurance may be more likely to have their peripheral artery disease treated by leg amputation rather than by limb-saving revascularization, it is not clear if this disparity occurs consistently on a national basis, and if it does so in a linear fashion, such that poorer individuals are at progressively greater risk for amputation.

Objective:

We undertook this study to determine if lower median household income and Medicaid/no insurance status are associated with a higher risk for amputation, and if this occurs in a progressively linear fashion.

Methods:

The National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample Database was queried to identify patients who were admitted with a diagnosis of critical limb ischemia from 2005 to 2014 and underwent either a major amputation or a revascularization procedure during that admission. Patients were stratified according to their insurance status and their median household income into four income quartiles. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine the effect of income and insurance status on the odds of undergoing amputation vs leg revascularization.

Results:

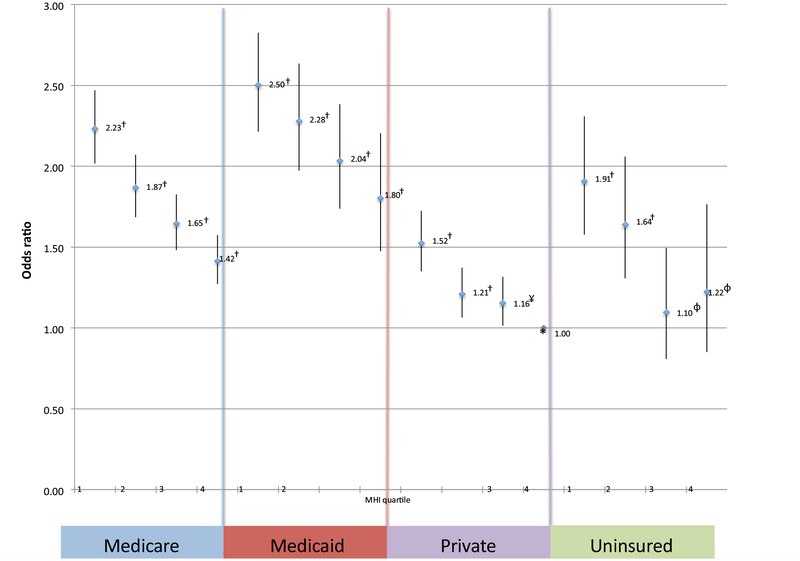

Across the different insurance types, there was a significant decrease in the odds ratios for amputation as one progressed from one MHI quartile to a higher one: namely, Medicare (2.23, 1.87, 1.65, and 1.42 for the first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles); Medicaid (2.50, 2.28, 2.04, and 1.80 for the first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles); private insurance (1.52, 1.21, 1.16, and 1.00 for the first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles), and uninsured (1.91, 1.64, 1.10, and 1.22, for the first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles).

Conclusions:

Lower MHI, Medicaid insurance, and uninsured status are associated with a greater likelihood of amputation and a lower likelihood of undergoing limb-saving revascularization. These disparities are exacerbated in stepwise fashion, such that lower income quartiles are at progressively greater risk for amputation.

Keywords: Peripheral artery disease, Amputation, Disparities, Revascularization

Significant disparities, such as differing prevalence, treatment, and overall outcomes, in the management of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) persist in the United States.1 Although most patients with PAD are not at a significant risk for limb loss, a small percentage of patients with PAD, namely, those presenting with critical limb ischemia, are at particularly high risk for major lower extremity amputation.2 For patients in this group, prompt revascularization is indicated for the purposes of limb salvage. Unfortunately, low socioeconomic status (SES)—as defined by low income and lack of private insurance—has been associated with a lesser likelihood of undergoing limb-salvage revascularization, and a greater likelihood of undergoing a major lower extremity amputation.3 A potential mechanism for this disparity is decreased access to care for those with low income.4 Remarkably, low-income patients, when they undergo revascularization procedures, are less likely to have successful outcomes, even when these procedures are performed at high-volume centers with overall excellent outcomes.5 It seems, therefore, that low income may not only decrease the likelihood of undergoing limb-salvage revascularization, but also increase the likelihood that a patient will undergo a major amputation, even if revascularization is undertaken. Indeed, a biology of poverty has been described, indicating a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and heart disease in individuals of low income and low educational attainment. Accordingly, it may well be that a biology of poverty is having an effect in these patients, leading to significantly more complex PAD. Although insurance type—specifically Medicaid—has also been associated with a higher likelihood of limb loss in patients presenting with limb ischemia, it is possible that Medicaid is simply a surrogate for low income.3

An association between low SES and overall cardiovascular disease has been relatively well-established.6,7 Although the association between low SES and specifically PAD was previously reported as inconsistent,8,9 Pande and Creager have, more recently, demonstrated this specific association for PAD more convincingly using a nationally representative sample of US adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.10 Although an increased prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and underuse of cardiovascular medications have also been described in the low SES population, these factors do not adequately explain the increased prevalence of PAD in individuals with low SES.11

In a national study, using data from the NIS Database, low income and racial/ethnic minority (particularly Black and Native American) patients presenting with limb ischemia were significantly more likely to undergo amputation vs revascularization.3 Although the risk factor of low SES, in this study, persisted even after controlling for insurance status, it remains possible that low SES could have led to inadequate insurance status months to years before admission, potentially leading to the undertreatment of vascular risk factors and predisposing these patients to a major amputation. The potentially confounding factor of insurance status, therefore, cannot be adequately excluded from this study. Indeed, the fact that Medicaid insurance was associated with a higher risk of amputation vs revascularization in this study may lend support to this theory. Hence, it remains unclear whether the higher risk of amputation is primarily related to insurance status or whether low SES, per se, leads to a greater likelihood for a major amputation vs a revascularization procedure. Moreover, the manner by which low income specifically relates to the likelihood of amputation has not been described. Thus, it is not clear whether poorer individuals are at greater risk for amputation in a progressively linear fashion. We, therefore, undertook this study to determine whether patient income and insurance status are associated with a progressively greater likelihood of amputation vs revascularization for patients presenting with limb ischemia.

METHODS

A query of the NIS database was performed to identify all patients who were admitted with a diagnosis of critical limb ischemia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, codes 440.22, 440.23, and 440.24) from 2005 to 2014. The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient care database in the United States, containing data on more than 7 million hospital stays.12 Those patients presenting with limb ischemia who also underwent either a revascularization procedure (percutaneous or open) or a major amputation (above-the-knee or below-the-knee amputation) were selected as the study sample. Patients who underwent both revascularization and a major amputation during the same hospitalization were excluded. This group was excluded to ensure the mutual exclusivity of the groups and allow a proper comparison of outcomes between the patient population in the revascularization group vs the amputation group. We believe that this exclusion prevents certain specific groups of patients from being included and potentially serving as problematic confounders. These groups include (1) patients who were incorrectly selected for revascularization, (2) patients properly selected for revascularization but failed owing to technical procedural errors, and (3) patients properly selected for revascularization but failed owing to some other patient factor, such as unreconstructible vascular disease identified at the time of angiography performed during an attempted endovascular limb-salvage procedure. Patients with acute limb ischemia were also excluded, because this factor is recognized as a separate and distinct disease entity from the focus of this article, which is chronic limb ischemia. Demographic data, comorbid conditions, and postoperative complications were recorded. Cardiac comorbidity was defined as the presence of congestive heart failure or coronary artery disease. Pulmonary comorbidity was defined as the presence of an existing pulmonary diagnosis. Renal comorbidity was defined as dialysis-dependent end-stage renal failure, and diabetes mellitus was defined as a diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 insulin-dependent or none insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. These patients were then stratified by median household income (MHI) and insurance status (ie, Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, and uninsured). MHI was classified by NIS predetermined quartile: 0 to 25th percentile (first quartile), 26th to 50th percentile (second quartile), 51st to 75th percentile (third quartile), or 76th to 100th percentile (fourth quartile) according in accordance with the residential zip code for each patient. Ranges vary slightly each year, in line with fluctuations in reported income. We used as reference point the values from 2010. Quartile cutoff points were defined in 2010 dollars to be $1 to $40,999 (first quartile), $41,000 to $50,999 (second quartile), $51,000 to $66,999 (third quartile), and $67,000 or greater (fourth quartile). Statistical analyses were done using the Student t-test to compare the differences among the groups and their means, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine the effect of income and insurance status on the odds of undergoing amputation vs leg revascularization while controlling for multiple factors, including race/ethnicity, age, smoking status, and underlying comorbidities. Given the nature of the study, using an administrative database with deindentified patient information, informed consent was waived.

RESULTS

The 10-year NIS query identified 162,249 patients presenting with critical limb ischemia who underwent either an open revascularization procedure (30%), an endovascular revascularization procedure (43.4%), or a major amputation (26.6%) during the same hospitalization (Table I). This was a primarily white (55%), male (57%) population with an average age of 69.9 years (Table II). Of these presenting patients, 34% lived in a zip code corresponding with the national MHI quartile 1, 27% in quartile 2, 22% in quartile 3, and 17% in quartile 4. Twenty-seven percent of patients with critical limb ischemia underwent a major amputation during their admission and 73% underwent a revascularization procedure. There were significant differences between the demographics of the two groups—for example, for revascularization vs amputation, blacks were over-represented in the amputation group, comprising a full 26% of patients undergoing amputation but only 15% of the patients undergoing revascularization. Table III shows significant differences in presenting comorbidities. Patients in the amputation group were more likely to present with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (62% vs 55%; P < .001), whereas patients in the revascularization group were more likely to be active smokers (15% vs 9.5%; P = < .001). Across the different insurance types, there was a statistically significant decrease in the odds ratios for amputation as one progressed from one household MHI quartile to another: namely, Medicare (2.23 [95% confidence interval [CI], 2.02–2.47; P < .001], 1.87 [95% CI, 1.69–2.07; P < .001], 1.65 [95% CI, 1.48–1.83; P < .001], and 1.42 [95% CI, 1.27–1.57; P < .001] for first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles, respectively), Medicaid (2.50 [95% CI, 2.21–2.83; P < .001], 2.28 [95% CI, 1.97–2.63; P < .001], 2.04 [95% CI, 1.74–2.38; P < .001], and 1.80 [95% CI, 1.47–2.21; P < .001] for the first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles, respecitively); private insurance (1.52 [95% CI, 1.35–1.72; P < .001], 1.21 [95% CI, 1.06–1.37; P < .001], 1.16 [95% CI, 1.01–1.32; P = .003], and 1.00 [reference] for the first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles, respectively), and uninsured (1.91 [95% CI, 1.58–2.31; P < .001], 1.64 [95% CI, 1.31–2.06; P < .001], 1.10 [95% CI, 0.81–1.50; P = .547], and 1.22 [95% CI, 0.85–1.76; P = .277] for the first, second, third, and fourth MHI quartiles, respectively; Fig 1). As compared with patients with private insurance in the highest MHI quartile, Medicaid (2.50), Medicare (2.23), and uninsured patients (1.91) at the lowest quartiles were two to three times more likely to undergo a major leg amputation.

Table I.

Treatment given to patients presenting with critical limb ischemia (N = 162,266)

| Procedure type | Percent |

|---|---|

| Open revascularization | 30.0 |

| Endovascular revascularization | 43.4 |

| Amputation | 26.6 |

Table II.

Patient demographics

| Variable | Overall (N = 162,266) | Revascularization (n = 119,089) | Amputation (n = 43,177) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 57.3 | 56.8 | 58.7 | <.001 |

| Female | 42.7 | 43.2 | 41.3 | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 55.1 | 58.3 | 46.2 | <.001 |

| Black | 18.1 | 15.4 | 25.6 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 8.3 | 8.0 | 9.3 | <.001 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | <.001 |

| Native American | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | <.001 |

| Unknown | 16.6 | 16.5 | 16.9 | <.001 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 75.3 | 74.1 | 78.6 | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 7.9 | 7.6 | 8.7 | <.001 |

| Private | 14.7 | 16.0 | 10.9 | <.001 |

| Uninsured | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.8 | <.001 |

| MHI | ||||

| $1–40,999 | 33.9 | 32.2 | 38.7 | <.001 |

| $41,000–50,999 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 27.2 | <.001 |

| $51,000–66,999 | 21.9 | 22.6 | 19.8 | <.001 |

| ≥$67,000 | 17.4 | 18.5 | 14.3 | <.001 |

| Median length of stay, days | 9.9 | 8.8 | 12.8 | <.001 |

| Mean age, years | 69.9 | 69.7 | 70.5 | <.001 |

Table III.

Preoperative comorbidities

| Comorbidity | Overall (N = 162,266) | Revascularization (n = 119,089) | Amputation (n = 43,177) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 56.9 | 55 | 62 | <.001 |

| Cardiac | 33.4 | 32.1 | 36.8 | <.001 |

| Respiratory | 17.3 | 17.7 | 16.3 | <.001 |

| Renal | 63 | 60.7 | 69.4 | <.001 |

| Smoking | 13.5 | 15 | 9.5 | <.001 |

Values are percentages.

Fig 1.

Odds ratio for undergoing an amputation. Likelihood of undergoing amputation based on insurance status and median household income (MHI) quartile. *Reference (private insurance fourth MHI quartile); †P < .001; ¥P = .003; φNot statistically significant.

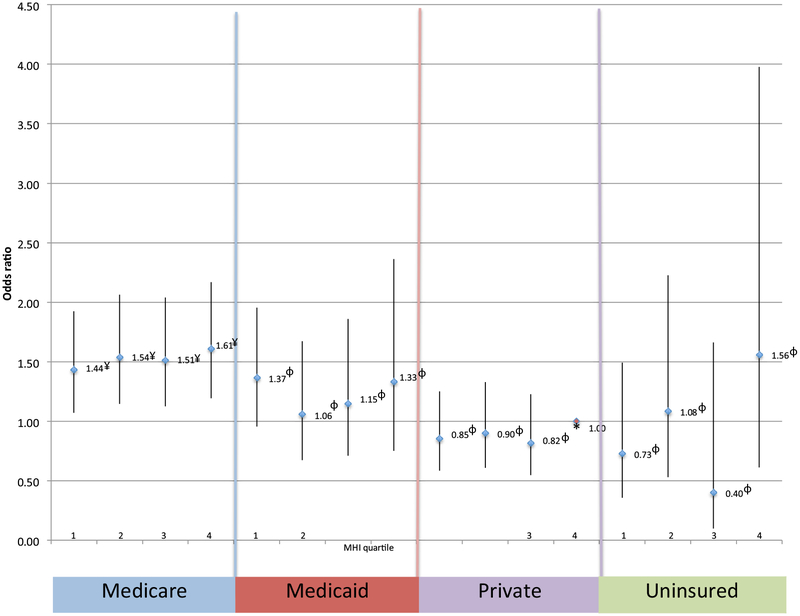

In terms of postoperative mortality, these disparities were more subtle. Among patients with Medicaid, private insurance, or uninsured, there was no significant increase in the likelihood of mortality across all MHI quartiles when compared with patients with private insurance in the highest MHI quartile (Fig 2). Although patients with Medicare demonstrated a significant increase in the likelihood of mortality (1.44 [95% CI, 1.07–1.92; P = .015], 1.54 [95% CI, 1.14–2.06; P = .004], 1.51 [95% CI, 1.12–2.04; P = .006], and 1.61 [95% CI, 1.19–2.17; P = .002]) when compared with privately insured patients in the highest MHI quartile, there was no significant difference in the mortality across the MHI quartiles for these patients. Postoperative outcomes were worse in the amputation group, with this group having a higher mortality rate (5.2% vs 2.0%; P = < .001), and worse postoperative morbidity when compared with the revascularization group (Table IV).

Fig 2.

Mortality after revascularization or amputation. Likelihood of mortality after revascularization or amputation based on insurance status and median household income (MHI) quartile. *Reference (private insurance fourth MHI quartile); ¥P < .05; φNot statistically significant.

Table IV.

Postoperative complications

| Overall (N = 162,266) | Revascularization (n = 119,089) | Amputation (n = 43,177) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No complications | 85 | 83.7 | 88.6 | <.001 |

| Complications | ||||

| Hemorrhage/hematoma | 3.3 | 3.9 | 1.4 | <.001 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.0 | <.001 |

| Wound infection | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.5 | <.001 |

| Cardiac complications | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | .816 |

| Respiratory complications | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | <.001 |

| Mortality | 2.9 | 2.0 | 5.2 | <.001 |

Values are percentages.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that, for patients presenting to a hospital with critical limb ischemia, low income as well as Medicaid and uninsured status are associated with significantly higher odds of receiving a leg amputation as opposed to revascularization. This finding is consistent with those by Henry et al.3 The unambiguous finding in the current study is the demonstration that this association occurs in a spectacularly linear fashion, with the disparity becoming progressively worse as one moves from one income quartile to a lower one. Disconcertingly, along with all of the other struggles that individuals at the lowest income levels routinely live with, they are also most likely to lose a leg and least likely to be revascularized after they present to a hospital with limb ischemia.

What remains unclear is whether this is a selection bias on account of their insurance status; or if poverty itself creates a type of aggressive form of limb ischemia, which is less amenable to arterial reconstruction; or whether this is primarily a function of delayed presentation, as has been reported previously.13,14 Indeed, several potential mechanisms have been postulated to explain this link between SES and PAD. First, inflammation, which is closely linked to vascular disease, has been implicated. This factor is suggested by the finding of higher inflammatory biomarkers in individuals of lower income and lower education.15,16 Second, psychological stress, which is known to have a deleterious impact on cardiovascular disease, has been reported to negatively impact the quality of life in patients with PAD.17,18 A third potential mechanism is the relatively new concept of allostatic load burden. Allostatic load refers to the cumulative effect of chronic wear and tear, leading to a biologic response pattern in which elements of the physiologic system-namely, the immune system, the sympathetic nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis-remain at heightened levels of activation.19,20

Whereas a potential mediating mechanism between PAD and SES is yet to be clearly elucidated, there is some evidence to suggest that low SES leads to worse outcomes in patients with PAD.11,21 Two European studies in nations where there is universal healthcare have also indicated worse outcomes in patients with low SES: a national study from Finland reported an increased risk of amputation in a diabetic population in patients of low SES, and a Dutch study showed worse survival after open surgery for PAD in patients of low SES.22 Although the Finnish population is clearly not adequately representative of the diverse population in the United States, this current study answers this question in a fairly definitive fashion.23

It was noteworthy to observe that the likelihood of amputation for patients with Medicare, although higher than private insurance, was significantly lower compared with Medicaid. This finding may suggest that, although Medicare may be associated with a lower likelihood of amputation as compared with Medicaid in the management of PAD, it may not necessarily be as beneficial as private insurance. If this observation is, in fact, accurate, then this finding portends certain interesting policy discussions around the argument for Medicare for all. Although insurance status correlated with the likelihood of amputation vs revascularization, a study of this nature is unable to determine causality, merely association. It is important to emphasize that this study was unable to evaluate patient behavior such as delayed presentation, which could have predisposed patients to amputation rather than revascularization.

In terms of mortality, our analysis did not parallel the findings seen in the amputation group. Patients with a lower SES did not have significantly worse outcomes in terms of mortality. It is gratifying that this clear correlation between amputation and SES was not also identified for mortality. However, we are unable to make any meaningful postulates regarding this finding.

There are several limitations associated with this study. The first major limitation is an inability to review any potential preoperative angiograms to determine how these patients for amputation vs revascularization were actually selected. This information may help to determine whether the greater selection of amputation for the lower SES patients is a factor of more severe disease or, perhaps, an as yet unexplained discriminatory factor. Given that our multivariate regression model controlled for diabetes mellitus, a greater severity of disease in the lower SES population may be a less likely explanation. Second, the actual state of the foot was not clearly delineated. It may well be that individuals of lower SES present to the hospital too late—with a foot that is already beyond salvage—leaving amputation as the more likely option. The nature of this study does not allow for the examination of either of these two critical factors. Third, using zip codes as a proxy for income assumes that all individuals living in a particular zip code necessarily belong to that zip code’s income bracket. Although this process may be very common, this assumption is not likely to be universally accurate. Although using household level income would provide us with a better index for SES, the lack of readily available and accurate individual data sources for a large population, such as the one used in a national inpatient database, makes zip code income quartiles the best proxy for neighborhood SES in large population studies. Furthermore, given that the NIS is an exclusive inpatient database, we are unable to comment on any potential outpatient revascularization efforts that may have been undertaken. In an effort to limit this inadequacy, we excluded patients presenting with chronic limb ischemia who did not undergo any procedures during their admission, so that presumably only those who required a relatively prompt procedure were included. This approach, in itself, could have introduced bias one way or another. Because the NIS databases do not allow us to determine whether any patients in the amputation groups had prior revascularization, we are not able to quantify how many patients in our amputation group might have undergone a revascularization procedure at some point in their lives. Other limitations include the ubiquitous drawbacks of large database studies, including potential errors in coding and sampling errors.24 One further limitation to note is that our large study population led to a significant statistical power that demonstrated statistically significant differences for small changes, such as in the preoperative comorbidities of our patient population; the actual clinical differences may be, essentially, inconsequential. Despite these limitations, we suspect that the very large sample size and the multivariate logistic regression methods used would likely help to significantly mitigate many of these limitations and produce some very meaningful results.

CONCLUSIONS

Lower SES, specifically, lower MHI, Medicaid insurance, and uninsured status, is associated with a higher likelihood of amputation and a lower likelihood of limb-saving revascularization. These disparities are exacerbated in stepwise fashion such that lower income quartiles are at a progressively higher risk of amputation. Future studies should examine the exact reasons for this disparity.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS.

Type of Research: Retrospective analysis of the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample database

Key Findings: Across insurance types, there was a statistically significant decrease in the risk of amputation as household income increased across the quartiles: namely, Medicare (2.23, 1.87, 1.65, and 1.42); Medicaid (2.50, 2.28, 2.04, and 1.80); private insurance (1.52, 1.21, 1.16, and 1.00; and uninsured (1.91, 1.64, 1.10, and 1.22).

Take Home Message: Lower socioeconomic status is associated with a greater likelihood of amputation and a lesser likelihood of limb-saving revascularization. These disparities are exacerbated in stepwise fashion such that lower income quartiles are at progressively greater risk for amputation.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number G12MD007597. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nguyen LL, Henry AJ. Disparities in vascular surgery: is it biology or environment? J Vasc Surg 2010;51:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg 2007;45: 65–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry AJ, Hevelone ND, Belkin M, Nguyen LL. Socioeconomic and hospital-related predictors of amputation for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2011;53:330–9.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soden PA, Zettervall SL, Deery SE, Hughes K, Stoner MC, Goodney PP, et al. Black patients present with more severe vascular disease and a greater burden of risk factors than white patients at time of major vascular intervention. J Vasc Surg 2017;67:549–56.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regenbogen SE, Gawande AA, Lipsitz SR, Greenberg CC, Jha AK. Do differences in hospital and surgeon quality explain racial disparities in lower-extremity vascular amputations? Ann Surg 2009;250:424–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation 1993;88: 1973–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karlamangla AS, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular risk in the United States, 2001–2006. Ann Epidemiol 2010;20: 617–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooks RN, Simonsick EM, Miles T, Newman A, Kritchevsky SB, Schulz R, et al. The association of race and socioeconomic status with cardiovascular disease indicators among older adults in the health, aging, and body composition study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57: S247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowkes FG, Housley E, Cawood EH, Macintyre CC, Ruckley CV, Prescott RJ. Edinburgh Artery Study: prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol 1991;20: 384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, Creager MA. Secondary prevention and mortality in peripheral artery disease: National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, 1999 to 2004. Circulation 2011;124:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subherwal S, Patel MR, Tang F, Smolderen KG, Jones WS, Tsai TT, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in the use of cardioprotective medications among patients with peripheral artery disease: an analysis of the American College of Cardiology’s NCDR PINNACLE Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.HCUP NIS Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wachtel MS. Family poverty accounts for differences in lower-extremity amputation rates of minorities 50 years old or more with diabetes. J Natl Med Assoc 2005;97: 334–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrissey NJ, Giacovelli J, Egorova N, Gelijns A, Moskowitz A, McKinsey J, et al. Disparities in the treatment and outcomes of vascular disease in Hispanic patients. J Vasc Surg 2007;46: 971–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamirani YS, Pandey S, Rivera JJ, Ndumle C, Budoff MJ, Blumenthal RS, et al. Markers of inflammation and coronary artery calcification: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis 2008;201:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalinowski L, Dobrucki IT, Malinski T. Race-specific differences in endothelial function: predisposition of African Americans to vascular diseases. Circulation 2004;109: 2511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aquarius AE, De Vries J, Henegouwen DPVB, Hamming JF. Clinical indicators and psychosocial aspects in peripheral arterial disease. Arch Surg 2006;141:161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stauber S, Guera V, Barth J, Schmid JP, Saner H, Znoj H, et al. Psychosocial outcome in cardiovascular rehabilitation of peripheral artery disease and coronary artery disease patients. Vasc Med 2013;18:257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duru OK, Harawa NT, Kermah D, Norris KC. Allostatic load burden and racial disparities in mortality. J Natl Med Assoc 2012;104:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson KM, Reiber G, Kohler T, Boyko EJ. Peripheral arterial disease in a multiethnic national sample: the role of conventional risk factors and allostatic load. Ethn Dis 2007;17: 669–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson HJ, Nightingale P, Pathak R, Jayatunga AP. The influence of socio-economic deprivation on rates of major lower limb amputation secondary to peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010;40:76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ultee KH, Bastos Gonçalves F, Hoeks SE, Rouwet EV, Boersma E, Stolker RJ. Low socioeconomic status is an independent risk factor for survival after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair and open surgery for peripheral artery disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015;50: 615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venermo M, Manderbacka K, Ikonen T, Keskimäki I, Winell K, Sund R. Amputations and socioeconomic position among persons with diabetes mellitus, a population-based register study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen LL, Barshes NR. Analysis of large databases in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:768–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]