Abstract

The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology. For additional information, and a full list of learning objectives for all three competencies, see http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289517715040.1

Keywords: pathology competencies, organ system pathology, nervous system—central, neuromuscular disorders, mitochondrial disorders, mitochondrial inheritance, mitochondrial myopathy

Primary Objective

Objective NSC4.2: Mitochondrial Disorders. Describe the etiology, pathogenesis, and clinical features of 2 types of mitochondrial diseases affecting muscle and explain why it may be important to obtain fresh frozen muscle to aid diagnosis.

Competency 2: Organ System Pathology; Topic NSC: Nervous System—Central Nervous System; Learning Goal 4: Neuromuscular Disorders.

Secondary Objectives

Objective GM1.6: Nonclassical Inheritance. Describe the pathophysiologic mechanisms that result in disorders of a nonclassical inheritance and mitochondrial inheritance and give clinical examples of each.

Competency 1: Disease Mechanisms and Processes; Topic GM: Genetic Mechanisms; Learning Goal 1: Genetic Mechanisms of Developmental and Functional Abnormalities.

Patient Presentation

A 38-year-old woman with no known medical issues presents to her primary care physician complaining of double vision. She first noted vision difficulties 2 months ago, when she started experiencing problems reading at night. She also feels generally weak, has fatigued easily with physical activity ever since childhood, and reports trips and falls that have increased in frequency over the past few years. A prior physician had started her on pyridostigmine with little improvement in eye symptoms after 6 weeks of treatment. Her 67-year-old mother also endorses vision problems, frequent falls, and easy fatigability.

Diagnostic Findings, Part I

On physical examination, the patient has bilateral eyelid ptosis, severely restricted extraocular movements in all directions, and mild weakness of proximal upper and lower extremities (movement possible against some resistance by the examiner; grade 4 of 5). The remainder of her neurological examination is unremarkable.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part I

What Is the Differential Diagnosis Based on Clinical Findings? What Diagnostic Tests Should Be Ordered?

This patient’s clinical syndrome (symmetric bilateral ptosis accompanied by progressive ophthalmoparesis) is known as progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO). The most common cause of PEO is an underlying mitochondrial disorder, but PEO can also be a sign of oculopharyngeal dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, and Graves’ disease. There are no sensory symptoms, arguing against peripheral nerve or spinal root involvement; however, electrodiagnostic testing (electromyography and nerve conduction studies) should be performed to help differentiate a primary myopathic process from a motor neuron disorder or a neuromuscular junction disorder. Additional laboratory tests are warranted to rule out rheumatologic disorders and endocrine abnormalities and to further rule in a primary muscle disorder. Electrocardiogram should be performed to evaluate for possible cardiac involvement.

Diagnostic Findings, Part II

Serum creatinine kinase was 432 U/L (normal level: 22-198 U/L). Rheumatologic workup showed lack of any autoantibodies, including acetylcholine receptor antibodies. The blood lactate concentration was normal and there were no abnormalities in the thyroid hormone levels. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and spinal cord revealed no significant abnormalities. Electrocardiogram was normal. Repetitive nerve stimulation studies did not show a decremental response, while electromyography results were consistent with a myopathic process without membrane instability.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part II

What Is the Differential Diagnosis Based on the Initial Diagnostic Findings? What Should Be the Next Step in the Diagnostic Workup?

The presence of objective extremity weakness is more consistent with a neuromuscular disease than Graves’ disease, which is further ruled out by normal thyroid hormone levels. Myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune neuromuscular junction disorder, is also unlikely, given the lack of decremental response on nerve conduction studies, the lack of antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies, and the lack of response to pyridostigmine. The elevated creatinine kinase level and the abnormal electromyography results both support a primary muscle disease. Genetic testing could be performed to rule out oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy; however, given that a mitochondrial disorder is the main differential diagnosis, the next recommended diagnostic step is to perform a muscle biopsy (which can differentiate between these 2 forms of myopathy and is generally needed for a definitive diagnosis of a mitochondrial disorder).

Diagnostic Findings, Part III

A muscle biopsy was performed and sent fresh to a specialized neuromuscular pathology laboratory to ensure appropriate tissue processing, which includes rapid freezing of a well-oriented portion of the specimen at ultracold temperatures (for cryosection histology and enzyme histochemistry), glutaraldehyde fixation of another portion (for electron microscopy), and snap freezing of the remaining tissue (for possible biochemical and molecular genetic studies).

Questions/Discussion Points, Part III

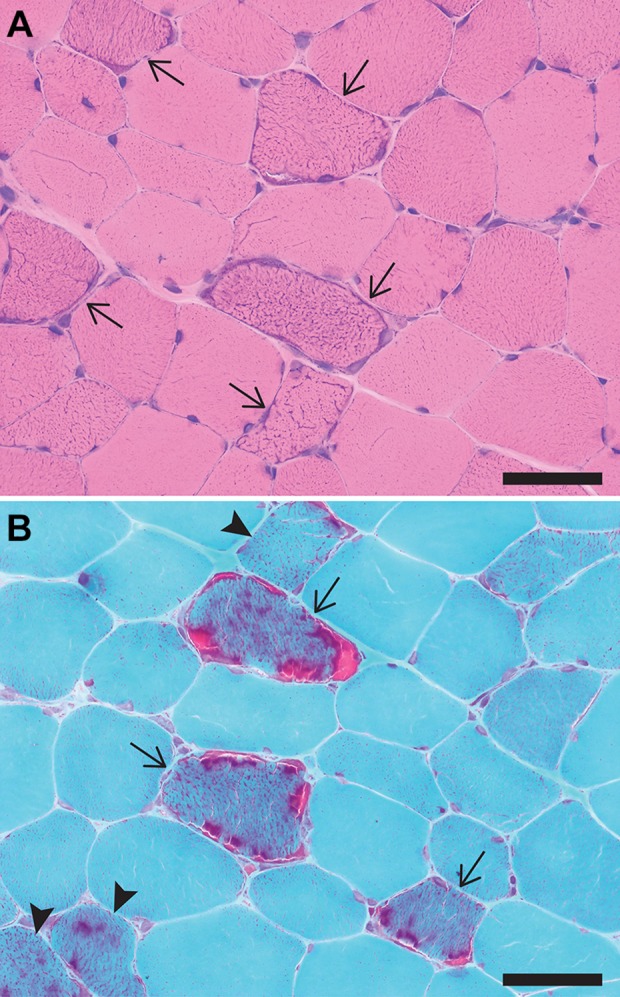

Routine Histologic Stains Performed on the Frozen Tissue Are Shown in Figure 1. What Abnormalities Are Present?

Figure 1.

A, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained cryosection showing fibers with an increase in subsarcolemmal and intersarcomeric blue staining (arrows) that are randomly distributed among muscle fibers with normal appearance. Note also the absence of chronic myopathic features (such as significant fiber size variation, endomysial fibrosis, and fiber splitting) that would be expected in a muscular dystrophy. B, Gomori trichrome-stained cryosection showing fibers with a marked increase in subsarcolemmal and intersarcomeric red staining (ragged red fibers; arrows) as well as fibers with a milder but abnormal increase in red staining (arrowheads). Scale bars: 100 µm.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained cryosections (Figure 1A) show randomly distributed muscle fibers with an increase in subsarcolemmal and intersarcomeric blue staining, which reflects mitochondrial hyperplasia. On cryosections stained with modified Gomori trichrome (Figure 1B), the abnormal fibers show prominent subsarcolemmal and intersarcomeric red staining (the so-called “ragged-red fibers”; arrows). A lesser degree of mitochondrial hyperplasia is seen in a few other fibers, which show an increase in sarcoplasmic red staining but do not have a fully developed ragged-red appearance (arrowheads). Mitochondrial hyperplasia seen on these stains is due to an increase in mitochondrial biogenesis, an attempt of the affected muscle fiber to compensate for the inadequate production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by dysfunctional mitochondria.

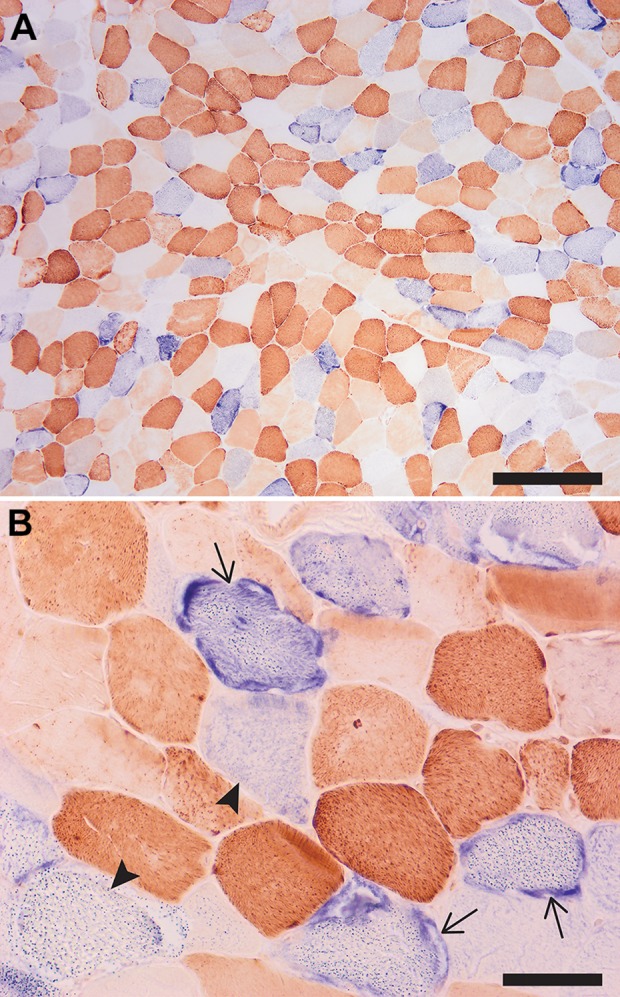

Additional workup routinely performed on the frozen muscle tissue includes oxidative enzyme stains; one of these additional stains (combined cytochrome C oxidase/succinate dehydrogenase [COX/SDH] enzyme histochemistry) is shown in Figure 2. What abnormalities are present?

Figure 2.

Low (A) and high (B) magnifications of a cryosection sequentially stained with COX (brown) and SDH (blue) enzyme histochemistry. The fibers with abnormal mitochondria are staining either dark blue (COX-negative fibers with mitochondrial hyperplasia, which correspond to ragged red fibers; arrows) or light blue (COX-negative fibers without mitochondrial hyperplasia; arrowheads), while fibers depleted of mitochondria lack both COX and SDH activity and appear white/optically clear. Note the mosaic pattern of affected and unaffected fibers; in a normal muscle, only dark brown (type 1) and light brown (type 2) fibers would be seen. Scale bars: (A) 500 µm and (B) 100 µm. COX indicates cytochrome C oxidase; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase.

A dual COX/SDH stain is performed to determine whether mitochondrial abnormalities seen on H&E and trichrome stains are due to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) or nuclear DNA alterations.2 The COX stain (brown) depends on the enzymatic activity of the respiratory chain complex IV, which is composed of subunits that are encoded by both mtDNA and nuclear DNA. Mutations in mtDNA often (although not always) impair synthesis of the mtDNA-encoded complex IV subunits; as a result, complex IV activity is attenuated or absent, and the affected fibers show either partial or complete lack of brown staining (the so-called “COX-negative fibers”). In contrast, SDH staining (blue) depends on the enzymatic activity of the respiratory chain complex II, the subunits of which are encoded entirely by nuclear DNA; as a result, this complex retains normal activity even when mtDNA mutations are present. Because these and other oxidative stains depend on the enzymatic activity of muscle fibers, they cannot be performed on fixed tissue.

In normal muscle, the brown chromogen (the result of COX activity) obscures the blue chromogen (the result of SDH activity), so no blue-appearing fibers are seen. The presence of a large number of blue (COX-negative, SDH-positive) muscle fibers is a diagnostic feature of mitochondrial myopathy caused by mtDNA mutations. (Note that because sporadic mtDNA mutations accumulate with age, a small number of COX-negative fibers can be seen in normal muscles of older individuals.) A mosaic pattern of normal and affected fibers seen in Figure 2 reflects mitochondrial heteroplasmy (variable mutation burden in different fibers) and is the expected finding in a mitochondrial disorder that is due to mtDNA mutations. In contrast, mutations in nuclear genes affect all mitochondria equally; on the dual COX/SDH stain, this type of defect either would result in no abnormalities or would manifest as a global deficiency of COX and/or SDH staining, depending on the mutation.

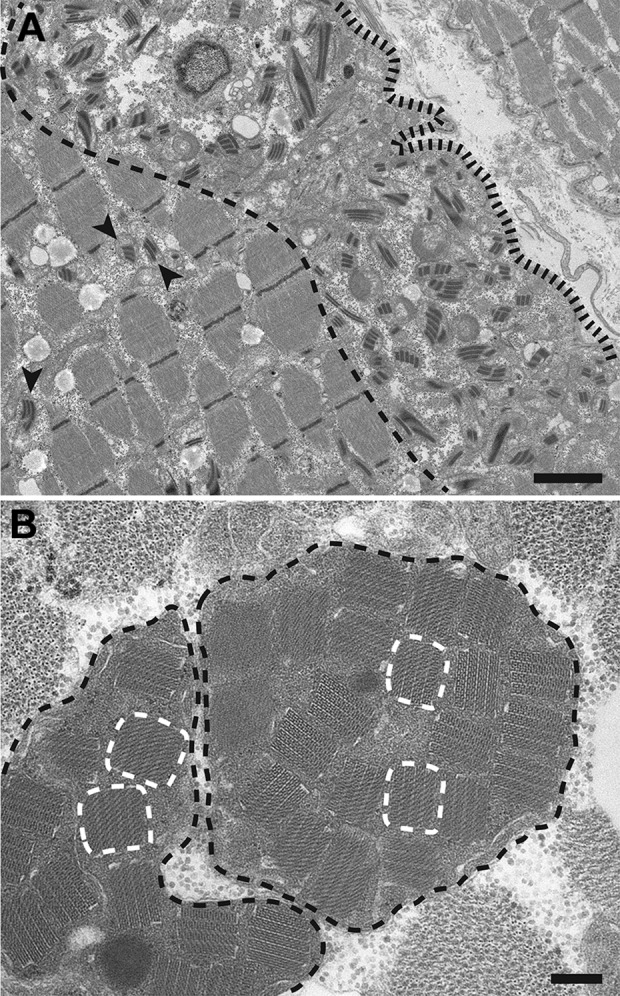

The Biopsy Is Further Evaluated by Electron Microscopy; Ultrastructural Findings Are Shown in Figure 3. What Mitochondrial Abnormalities Are Present?

Figure 3.

A, Low magnification electron micrograph from a longitudinal muscle section showing a subsarcolemmal collection of abnormal mitochondria, which demonstrate a significant variation in the size and shape and contain “railway track”-like crystalline inclusions. (The subsarcolemmal zone is found between the sarcolemma [delineated by a black fence-like line] and the edge of the myofibrillar apparatus [delineated by a black dashed line]). The abnormal mitochondria are mostly found within this subsarcolemmal area, but can also be seen between the myofibrils (arrowheads). B, High-magnification electron micrograph from a muscle cross section shows 2 giant mitochondria (outlined by the black dashed lines) that are distended by crystalline inclusions with a “parking lot” appearance, a few of which are delineated by the white dashed lines. Scale bars: (A) 2 µm and (B) 0.2 µm.

Ultrastructural evaluation shows mitochondrial hyperplasia, which is most prominent in the subsarcolemmal areas. In addition, abnormal mitochondria show marked variation in their size and shape (Figure 3A). Finally, many mitochondria contain crystalline inclusions, which have a “railway track” (Figure 3A) or a “parking lot” (Figure 3B) appearance and are mainly composed of mitochondrial creatine kinase.3 Although formation of these crystalline inclusions can be induced by creatine depletion or ischemia in experimental animals, their presence in human muscle biopsies is pathognomonic for a mitochondrial myopathy.4,5

What Is the Histopathologic Diagnosis?

Taken together, the findings of marked mitochondrial hyperplasia (ragged-red fibers), abnormal respiratory chain activity (COX-negative, SDH-positive fibers), and abnormal mitochondria with crystalline inclusions on electron microscopy are diagnostic of a mitochondrial myopathy.

What Is the Integrated Clinicopathologic Diagnosis?

Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia

The final diagnosis of a mitochondrial disorder requires integration of history and physical examination findings with histopathologic, biochemical, and genetic testing results. Although PEO can be (and often is) a component of a larger mitochondrial disorder syndrome, no extramuscular symptoms were present in this case, so the patient was diagnosed with an isolated chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO).6

Mitochondrial disorders comprise a clinically and biochemically heterogeneous group of diseases that are due to dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which consists of 5 large enzyme complexes and is critical for the production of adequate supply of ATP. Each cell contains multiple mitochondria; more metabolically active cells may have thousands. Each mitochondrion contains multiple copies of a 16.6-kb circular mtDNA, which is composed of 37 genes encoding 13 oxidative phosphorylation machinery proteins, 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and 2 ribosomal RNAs; the remaining approximately 1500 mitochondrial proteins (respiratory chain complex subunits, respiratory chain complex assembly factors, and mtDNA maintenance proteins) are encoded by nuclear DNA.7 As a result, alterations in either mitochondrial or nuclear DNA can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction. Since a single mitochondrion contains approximately 10 copies of the mitochondrial genome, and each cell contains many mitochondria, both mutant and wild-type mtDNA can coexist in a single cell. The proportion of functional and dysfunctional mitochondria differs among different cells and tissues; the degree of this heteroplasmy usually affects the severity of the disease phenotype (patients with more cells that have a larger proportion of dysfunctional to functional mitochondria usually have worse symptoms).

The prevalence of mitochondrial disorders has been reported at 1 in 10 000.8 They have variable clinical presentations with regard to age of onset, organ system involvement, severity of symptoms, and prognosis. Organ systems with high metabolic activity tend to be more affected; skeletal muscle involvement is particularly common and most often presents as PEO (as in this case), most likely because extraocular muscles have particularly high-energy requirements and contain more mitochondria than other skeletal muscles. Other common symptoms of mitochondrial dysfunction include sensorineural hearing loss, short stature, cardiomyopathy with conduction deficits, peripheral neuropathy (including optic neuropathy), encephalopathy with or without seizures, and diabetes; less commonly, there is gastrointestinal dysmotility, liver failure, pancytopenia, and pancreatic failure.9

What Is the Most Likely Genetic Abnormality Present in This Case? Should Any Additional Testing Be Considered?

Some mitochondrial disorders are caused by point mutations in mtDNA, most commonly in 1 of 22 tRNAs (mutations of which affect synthesis of multiple respiratory chain subunits). Other mitochondrial disorders are caused by small or large mtDNA deletions. Mutations in nuclear genes that are required for mtDNA replication and maintenance, such as mitochondrial polymerase γ (POLG), can lead to mtDNA depletion and/or multiple mtDNA deletions. Given the mosaic pattern of normal and abnormal fibers in the patient’s muscle biopsy, the underlying mutation (or mutations) is more likely to be present in her mtDNA rather than in her nuclear DNA. However, several different mtDNA abnormalities can cause CPEO; therefore, additional molecular genetic testing will be required to identify the specific underlying genetic abnormality.

Although specific genetic alterations have been associated with some syndromic presentations, the genotype–phenotype relationship in mitochondrial disorders is complex (a single mutation can cause several different clinical syndromes, while each syndrome can be caused by different genetic alterations). One example is that of MELAS, a multi-organ disease with features of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes. The m.3243A>G point mutation in the mtDNA gene MT-TL1 (which encodes a specific mitochondrial tRNA) is found in 80% of individuals with MELAS; however, this mutation can also cause CPEO or maternally inherited diabetes and deafness, while MELAS can also be caused by other mtDNA mutations.9,10 Myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers, another common mitochondrial disorder syndrome, is also most often caused by tRNA point mutations.9 In contrast, CPEO (the most common clinical manifestation of mitochondrial cytopathy) can be caused by mtDNA point mutations, single or multiple mtDNA deletions, and mutations in nuclear genes that lead to impaired mtDNA maintenance or nucleotide metabolism.6

Diagnostic histologic findings of a mitochondrial cytopathy develop over time and are often absent in children with mitochondrial disease. If an alteration in nuclear DNA is suspected, blood samples may be used for DNA sequencing tests. However, if an alteration in mtDNA is suspected, a muscle or other tissue sample is required and can be used to sequence both mtDNA and nuclear DNA. Multiple techniques varying in cost and coverage can be used to confirm the presence of genetic alterations (multigene panels, exome sequencing, mtDNA sequencing).7 Even in patients with histopathologically diagnosed mitochondrial disorders (as in this case), identification of specific genetic alterations aids disease management and helps guide genetic counseling for patients and their families. Another diagnostic option is to analyze electron transport chain function by testing biochemical activity of individual respiratory chain complexes on fresh or frozen muscle homogenates; fixed tissue or tissue lacking mitochondria will not show positive electron transport chain activity.7 Because of heteroplasmy/tissue mosaicism associated with mtDNA mutations, these biochemical tests are generally more informative in pediatric patients who are more likely to harbor inherited mutations that affect mitochondria globally.

What Is the Most Likely Inheritance Pattern in This Case?

Inheritance patterns for mitochondrial myopathies differ depending on the causative genetic alteration.11 Autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive inheritance can occur in cases of altered nuclear DNA. A germline mutation, inherited from either or both parents, would be present in the nuclear DNA of all cells in the offspring. In the case of mitochondrial inheritance, dysfunctional mtDNA would only be passed from mother to offspring. Mitochondria in the oocyte provide the original pool of mtDNA for the offspring; if some of these mitochondria contain altered mtDNA, a mitochondrial disorder will be maternally inherited. Depending on how mitochondria are subdivided in subsequent cellular divisions, there may be variable distribution of functional and dysfunctional mitochondria in different tissues and cell lines. Finally, sporadic mutations in either nuclear DNA or mtDNA can result in sporadic, uninherited mitochondrial diseases. In our case, the patient’s biopsy findings suggest an mtDNA disorder and her mother exhibits similar symptoms, so maternal inheritance is likely; however, autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive inheritance of a mutation in an mtDNA-maintenance gene is also possible. Thus, molecular genetic evaluation will be necessary for proper genetic counseling and family planning.

Teaching Points

Mitochondrial cytopathies are disorders of oxidative phosphorylation and are caused by genetic alterations in either nuclear DNA or mtDNA that ultimately lead to dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (which is responsible for the bulk of energy production in a cell). Although mitochondrial disorders can affect multiple organ systems throughout the body, the clinical consequences of the resulting metabolic deficiency are typically most harmful for energetically demanding postmitotic tissues (such as skeletal muscle, brain, and myocardium).

Patients with mitochondrial disorders almost always present with muscle weakness, but additional findings are common and include sensorineural hearing loss, short stature, cardiomyopathy, peripheral neuropathy, encephalopathy, and diabetes. Diagnostic workup should be targeted at excluding other neurogenic, autoimmune/rheumatologic, and metabolic disease processes.

Depending on the nature of the causative mutation, inheritance of mitochondrial disorders can be maternal, autosomal dominant, or autosomal recessive. In addition, mitochondrial disorders can arise sporadically through acquired/somatic mutations of mtDNA.

Depending on how mitochondria segregate during cell division, the proportion of functional to dysfunctional mitochondria can vary between individual cells and tissues; this variation in the cellular mutation burden (heteroplasmy) is most prominent when the underlying disease cause is an mtDNA mutation.

Histologic features of mitochondrial myopathy are ragged-red fibers and COX-negative, SDH-positive fibers that are interspersed among normal-appearing fibers in a mosaic pattern. The biopsied muscle tissue can be also be used to identify the underlying mtDNA alterations, which are detectable even in samples that lack classic histologic findings.

Fresh or frozen tissue muscle is needed to perform enzyme histochemistry and functional assays of mitochondrial enzyme activity and is the optimal tissue for molecular genetic studies of mtDNA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The article processing fee for this article was funded by an Open Access Award given by the Society of ‘67, which supports the mission of the Association of Pathology Chairs to produce the next generation of outstanding investigators and educational scholars in the field of pathology. This award helps to promote the publication of high-quality original scholarship in Academic Pathology by authors at an early stage of academic development.

ORCID iDs: Calixto-Hope G. Lucas  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8347-9592

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8347-9592

Marta Margeta  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6889-2488

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6889-2488

References

- 1. Knollmann-Ritschel BEC, Regula DP, Borowitz MJ, Conran R, Prystowsky MB. Pathology competencies for medical education and educational cases. Acad Pathol. 2017;4 doi:10.1177/2374289517715040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Milone M, Wong LJ. Diagnosis of mitochondrial myopathies. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stadhouders AM, Jap PH, Winkler HP, Eppenberger HM, Wallimann T. Mitochondrial creatine kinase: a major constituent of pathological inclusions seen in mitochondrial myopathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5089–5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O’Gorman E, Fuchs KH, Tittmann P, Gross H, Wallimann T. Crystalline mitochondrial inclusion bodies isolated from creatine depleted rat soleus muscle. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1403–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vincent AE, Ng YS, White K, et al. The spectrum of mitochondrial ultrastructural defects in mitochondrial myopathy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mcclelland C, Manousakis G, Lee MS. Progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:53 doi:10.1007/s11910-016-0652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahmed ST, Craven L, Russell OM, Turnbull DM, Vincent AE. Diagnosis and treatment of mitochondrial myopathies. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:943–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schaefer AM, Mcfarland R, Blakely EL, et al. Prevalence of mitochondrial DNA disease in adults. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pfeffer G, Chinnery PF. Diagnosis and treatment of mitochondrial myopathies. Ann Med. 2013;45:4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Hattab AW, Adesina AM, Jones J, Scaglia F. MELAS syndrome: clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116:4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alston CL, Rocha MC, Lax NZ, Turnbull DM, Taylor RW. The genetics and pathology of mitochondrial disease. J Pathol. 2017;241:236–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]