Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine associations between perceived neighborhood food environments and food purchasing at small and non-traditional food stores. Intercept interviews of 661 customers were conducted in 105 small and non-traditional food stores. We captured (1) customer perceptions of the neighborhood food environment, (2) associations between customer perceptions and store-level characteristics, and (3) customers’ perceptions and shopping behaviors. Findings suggest that customers with more favorable perceptions of the neighborhood food environment were more likely to purchase fruits and vegetables, despite no significant association between perceptions of the neighborhood and objectively measured store characteristics.

Keywords: Food Environment, Perceptions, Purchasing, Shopping Behaviors, Fruit, Vegetables, Small Food Stores, Non-Traditional Stores

Introduction

Fruits and vegetables (F&V) are essential components of a healthy diet. A diet rich in F&V has been associated with lower blood pressure,1,2 reduced heart disease,3–6 and cancer risk.7 Access to supermarkets and large grocers has been linked to greater consumption of F&V as well as overall healthier diets.8–13 However, small food retailers (e.g., corner stores) are also a common food source for many people in the U.S., especially those persons living in urban and low-income neighborhoods.14–17 Research on the use of small food stores has increased in recent years with customers reporting visits to these stores as often as every day or multiple times per week.18–24 Likewise, non-traditional food retailers, such as gas-marts, pharmacies, and dollar stores, have also been recognized as a common food sources in the urban food environment.25–27 In particular, pharmacies and dollar stores have increased in the market share of food retailers,28,29 and in many geographic regions of the US, these stores can be located in low-income neighborhoods or food deserts.30 Although, the inclusion of these non-traditional stores in food environment research is limited, recent research efforts in Minneapolis-St. Paul have demonstrated that nearly 85% of pharmacies and 92% of dollar stores sell some type of fruit and vegetables, and 23% of pharmacies sell fresh fruits and vegetables.27

Unfortunately, food purchases at small and non-traditional food stores have been associated with energy-dense and poor quality food choices,23,31–33 and purchasing food from small stores has been linked to increased obesity risk and other poor health outcomes.34–36 Less healthy products, such as sugar-sweetened beverages and snacks, are typically featured in these stores via advertisements, favorable product placement, and price promotions.37–40 However, many efforts are now underway to improve small food store purchases across the U.S. through policies and programs addressing both the kind of food that is stocked and how it is marketed.16,26,41,42 Evaluations of such efforts have demonstrated successful improvement in various features of the store environment, including availability, visibility, affordability, and promotion of healthy foods.43

Beyond store features and marketing, a number of studies have demonstrated that residents’ with favorable perceptions of the neighborhood retail food environment may have healthier diets.8,44–48 For example, those who report more healthful food quality, selection, and affordability in their own neighborhood report higher F&V intake.9,49,50 Indeed, residents’ perceptions of the food environment may be even more relevant to dietary behaviors than objective food environment features because they account for constraints in access and other cognitive processes relevant to behavior.8 In a recent study of a new supermarket opening in a food desert, Dubowitz and colleagues found significant improvements in overall dietary quality among residents who lived near the new store; however, the mechanisms of this impact appeared not to be related to use of the new supermarket per se, but instead may be linked to improved perceptions of the neighborhood food environment and neighborhood satisfaction.51

Research on food environment perceptions generally has been limited to the neighborhood in which the resident lives; little is known about whether the food environment around a particular store is related to the healthfulness of customers’ purchasing behavior. The neighborhood around a given food store, or simply an individual’s perception of that neighborhood, might encourage more or less healthful purchases. For instance, some food shoppers travel to neighborhoods outside their own in order to do their grocery shopping based on factors such as convenience, price, and perceived quality of the store.52,53 Additionally, many studies have argued that food shopping is complex and it cannot be assumed that any one single factor determines where people shop.54 Based on these facts, it is reasonable to hypothesize that if a store’s environment is perceived as healthful, it may draw people who intend to purchase F&Vs. As yet, perceptions of the environment around the food store where people shop have not been fully explored.

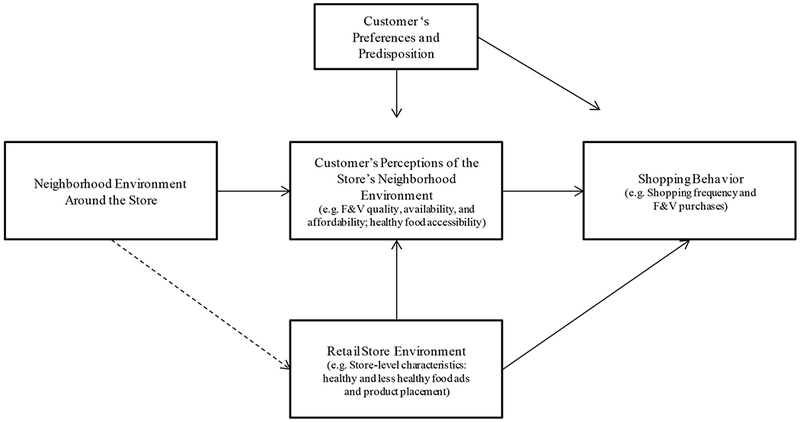

The purpose of this paper was to examine customers’ perceptions of the neighborhood food environment surrounding small and non-traditional food stores and their food purchasing behaviors. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model of the hypothesized relationships between these constructs. We proposed that customers’ perceptions of the store’s neighborhood environment can be influenced by the overall neighborhood environment surrounding the store, a customer’s preferences and predisposition, as well as the characteristics of the retail store itself. Additionally, a customer’s shopping behavior may be influenced by their perception of the store’s neighborhood food environment, their own personal preferences and predisposition, as well as the store’s characteristics. In this study, we examined two of these relationships.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

First, we tested the association between store-level characteristics (e.g., healthy and less healthy food advertisements and product placement) and customer perceptions of the neighborhood environment. We hypothesized that customers’ perception of the neighborhood food environment around the store would be healthier (e.g., higher agreement of availability, affordability, quality and/or ease of obtaining F&V in that neighborhood) if the store marketing features were healthier. Secondly, we examined the associations between customer perceptions and their shopping behaviors (e.g., shopping frequency and purchases of F&V). We hypothesized that customers who perceived the neighborhood food environment around the store to be healthier would shop more frequently at the store and purchase more F&Vs, while customers who perceived the neighborhood food environment to be less healthy around the store would shop less frequently at the store and purchase fewer F&Vs. Understanding the role of customer perceptions could provide insight into how future interventions and initiatives could be tailored to improve food purchases at small food stores.

Methods

This study was based on baseline (pre-policy) data collected through a larger research effort to evaluate the Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance,55 a local policy requiring licensed grocery stores to stock minimum amounts and varieties of specific foods, including F&V, whole grains, and low-fat dairy. The evaluation included stores in Minneapolis, Minnesota and St. Paul, Minnesota as comparable controls. Data were collected between July and November 2014 (pre-policy), recruiting participants as they exited food stores. All eligible stores were determined from a list of licensed grocers provided by the Minneapolis Health Department and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota approved this study.

Stores were excluded if the licensing address was invalid and/or it was not expected to stock a wide variety of foods, including those consisting of ≤ 100ft2 of retail space and those located in the downtown commercial districts. In addition, stores participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which includes specific program requirements regarding stocking healthy, staple foods were also excluded from our sample. Further details on store eligibility are published elsewhere.33

Out of 255 eligible stores, 180 were randomly selected to participate. Customers exiting these stores were successfully recruited to participate in intercept interviews at 106 of these stores (63 in Minneapolis and 43 in St. Paul). Of the 74 stores where customer intercept interviews were not completed, 20 were identified as ineligible upon visiting the store (e.g., due to new participation in WIC), 32 refused to participate, and in the remaining 22 stores, no participants were successfully recruited. Data on each store, including store type, were collected during a separate visit to assess a range of store characteristics. All stores could be categorized as a corner store, gas-mart, pharmacy, dollar store, or general retailer based on store characteristics via in-person store audits. For instance, a store was classified as a pharmacy if prescriptions could be filled at the retailer. Large retail pharmacy vendors included “Walgreens” and “CVS.” Dollar stores were defined as any retailer providing discount home and food goods, but were not primarily a food retailer or gas-mart. Examples of dollar stores were “Dollar Tree” and “Family Dollar.” Gas-marts were distinguished from corner stores, by the present of gas pumps. In analyses, we excluded the one large general retailer based on its size and lack of similarity to the other store types; our final sample of stores where customer intercepts were conducted was 105. For a subset of our analyses that also utilized observational store-level data, our analytic sample including 99 stores where both customer intercept surveys and store assessment data were collected.

Measures

Customer Intercepts

In teams of two, data collectors visited stores and obtained permission from an employee to recruit customers exiting the store. Data collectors attempted recruitment for 30 minutes; if at least one survey was completed, they stayed an additional 15-30 minutes. Eligible participants were English-speakers who were ≥18 years old and who made a food or beverage purchase at the store. Data collectors recorded participants’ food and beverage purchases (quantity, size, product name, and price paid) and administered a brief survey. In total, 661 participants were recruited. The process detailing recruitment is further described elsewhere.56 The participation rate was 35%. Many stores in this sample were used for more than food shopping, so not every customer made a food/beverage purchase; recruitment data suggest that 41% of customers exiting the store made no food or beverage purchases.56

Customer Characteristics and Shopping Behavior

Data on participant demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment), were obtained from the intercept survey. Shopping behavior was characterized as the frequency with which each participant shopped at the store (e.g., at least once a day, 1-6 times a week, and once a week or less).

Perceived Neighborhood Food Environment

Perceived F&V availability within the neighborhood of the store was measured using three questions. Participants were asked the extent to which they agree with the following: (1) “The fresh fruits and/or vegetables in this neighborhood are of high quality,” (2) “A large selection of fresh fruit and/or vegetables is available in this neighborhood,” and (3) “Fruits and vegetables are affordable at the stores in this neighborhood.” Survey responses were: “strongly disagree” (1), “disagree” (2), “neither agree nor disagree (neutral)” (3), “agree” (4), and “strongly agree” (5); (“don’t know” was a response option coded to missing). For analysis purposes, responses were scaled to range from 0 to 4, with a score 0 indicating the lowest perception and a score of 4 indicating the highest. For ease of interpretation, each question was dichotomized into “Do not agree’ (≤2) and ‘Agree’ (≥3) categories.57 A summary score for overall fruit and vegetable perceptions was also created by adding the three perception variables.48,58,59 Summary scores ranged from 0 to 12, with 0 indicating strong disagreement that F&V were high quality, available, and affordable in the neighborhood. This score was also dichotomized into ‘high agreement’ (≥9) (where individuals ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ with all three survey items) versus ‘low agreement’ (≤8).

To assess overall perception of healthy food in the neighborhood, participants were also asked if they agreed with the following: “It is easy to find healthy foods in this neighborhood.” These questions used the same 5-point Likert scale, as described above.

Fruit and Vegetable Purchases

Using the intercept survey, each participant was queried on whether they “have ever bought fresh fruits and vegetables at the current store?” (Yes/no). In addition, data on food/beverage purchases at the time of the interview were entered by trained study staff into Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR), a nutrient analysis program. To characterize food/beverage purchases, the categories available in NDSR were collapsed into 24 mutually exclusive categories (17 food categories, 7 beverage categories). A comprehensive description of these categories has been described elsewhere.33 Only the F&V categories were utilized in this paper. For each participant purchase, the total number of servings of each fruit/vegetable category was calculated. If the total servings for all F&V combined was ≥ 1 (e.g., ≥1/2 cup), the participant was categorized as having purchased a serving or more of F&V.

Store Characteristics

Store assessments were also conducted for each store. We measured the amount (in pounds) and number of varieties of F&V in each store. Amount was a continuous measure of the total pounds of fresh and/or plain frozen (with no sugar added) F&V. Due to a skewed distribution we created a 4-level categorical measure for analysis (none, 1-18, 19-50, and >50). We also measured the total varieties of fresh, frozen and canned F&V. This measure only included canned fruit packed in 100% juice, and plain canned vegetables with nothing added except salt. This was also a skewed measure which we categorized into three levels (0-5, 6-12, and >12).

In addition, the presence of advertisements for healthy and less healthy foods and beverages were recorded. Data were collected based on a retail scoring system, which has demonstrated good inter-rater and test-retest reliability.56 Our study team modified the tool focusing on the presence (≥ 1) of exterior and interior healthy and unhealthy food advertisements and product placement within stores.38 Healthy foods included F&V, whole grains, beans, nuts and seeds, non-fat/low fat milk products, lean meat, poultry, fish, and black coffee. These include minimal or no added fat, sugars, or sweeteners. Less healthy food included high calorie, low nutrient foods and beverages including alcoholic beverages, soft drinks and other sweetened beverages including diet drinks, sweet desserts and highly sugared cereals, chips and other salty snacks, most solid fats, fried foods, and other foods with high amounts of sugar, fat, and/or sodium. To assess product placement (e.g., impulse buys), research staff recorded: 1) if fresh produce (fruits and vegetables) could be seen from the front entrance; 2) the presence of less healthy food items within reach of the cash register including gumball machines, candy, soda, chips, and other food/beverage items (e.g., energy drinks, beef jerky, cookies, donuts, ice cream, and pastries); and 3) the presence of healthy food items within reach of the cash register including trail mix/granola (no added sugar), bagged nuts/seeds (no added sugar), fresh fruit, bottled water, 100% fruit juice, and other food/beverage items (as specified).

Finally, a neighborhood socioeconomic status variable was measured as the percent of families in each store’s census tract living on <185% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Specifically, each store’s address was geocoded within ArcGIS 10.3 (Esri, Redlands, CA), and the corresponding percent of households meeting the poverty criteria was assigned using 2013 American Community Survey (ACS) data.60 In addition, the reported cross streets of each customer’s home and the store’s address were used to determine how far away customers lived from the store.

Statistical Analysis

The primary unit of analysis was the customer purchase and intercept event. Of the 661 eligible customers, descriptive statistics, percentages or mean (SD), for all measures including customers’ demographic characteristics, shopping behaviors, and perceptions of the neighborhood food environment were performed. Store-level characteristics including F&V availability and the presence of healthy and unhealthy ads and products are also described. For all measures, we calculated descriptive statistics across the full sample and by each of the store types where customers made purchases. For comparisons by store type, either Chi-square tests (for categorical variables where all cells had expected frequency ≥5), Fisher exact tests (for categorical variables if some cells had expected frequency <5), or analyses of variance, ANOVA (for means), were performed.

Neighborhood food environment perception measures were analyzed relative to store-level characteristics using generalized linear models. For these models, data was restricted to the 99 stores and 594 customer intercepts where data was collected on both customer perceptions (from customer intercepts) and store characteristics (from store assessments). All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, employment, and store type and neighborhood-level poverty as fixed effects and store ID as random effect due to nesting of individuals within stores. The adjusted least square means (lsmeans) were compared to account for any within group differences.

Logistic regression was used to assess the bivariate and multivariate associations between all three dependent shopping behavior variables (shopping frequency, ever purchasing F&V, and the purchase of at least one serving of F&V at the time of intercept) and the independent perceptions variables, including perceived quality, availability, and affordability of F&V (three individual variables and one summary variable) and perceived ease of finding healthy foods. Models included age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, employment, and store type and neighborhood-level poverty as fixed effects and store ID as random effect due to nesting of individuals within stores. For all analyses, a p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant and all analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Participant characteristics including demographics and shopping behaviors are presented in Table 1 for the overall sample and by store type. On average, participants were 40 years of age and majority were male (57%) across all store types. Forty-seven percent of participants were non-Hispanic White, 36% non-Hispanic Black; small percentages of shoppers were Hispanic, non-Hispanic Native American/Alaska Native, Asian, multi-racial, or other (3-4% each). Nearly two-thirds of participants (63%) had at least some college education. Using geographic methods, we determined that 50% of participants lived within less than a mile away from the store. The overall mean distance was 3.3 miles for all stores.

Table 1.

Customer-, store- and neighborhood-level characteristics for customer intercepts at all stores and at each of four store type: mean (sd) or percentage

| All stores | Corner/small grocery stores | Food/Gas marts | Dollar stores | Pharmacies | p1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer-level Characteristics | n=661 | n=194 | n=268 | n=67 | n=132 | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | 40 (15) | 38 (13) | 40 (15) | 44 (15) | 42 (17) | .01 |

| BMI | 28 (6) | 28 (6) | 28 (7) | 28 (7) | 28 (7) | .65 |

| Gender: male | 57 | 55 | 64 | 48 | 48 | .009 |

| Race/ethnicity | <.0001 | |||||

| Hispanic | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| Non-Hispanic | ||||||

| White alone | 47 | 37 | 51 | 27 | 63 | |

| Black alone | 36 | 44 | 30 | 50 | 29 | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native alone | 4 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 1 | |

| Asian alone | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Other race alone | 4 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 | |

| Multi-racial | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Education | <.0001 | |||||

| High school diploma or less | 38 | 41 | 39 | 52 | 21 | |

| Some college | 37 | 32 | 34 | 37 | 49 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 26 | 27 | 27 | 10 | 30 | |

| Employment | .002 | |||||

| Employed | 64 | 60 | 71 | 51 | 60 | |

| Unemployed/disability | 26 | 33 | 19 | 31 | 25 | |

| Other (student, retired) | 11 | 7 | 10 | 18 | 15 | |

| Distance from home to store (miles) | 3.3 (6.2) | 1.9 (4.5) | 4.2 (5.8) | 3.2 (10.3) | 3.4 (6.2) | .003 |

| Shopping Behaviors | ||||||

| Shopping frequency | <.0001 | |||||

| At least once a day | 29 | 39 | 30 | 33 | 11 | |

| 1-6 times a week | 44 | 37 | 45 | 47 | 50 | |

| Less than once a week | 27 | 24 | 26 | 20 | 39 | |

| Ever purchased fruit and vegetables at store | 33 | 44 | 41 | 12 | 13 | <.0001 |

| Purchased at least one serving of fruit and/or vegetables at time of intercept | 8 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 8 | .66 |

| Perceptions of Neighborhood Food Environment | ||||||

| Fresh fruit and vegetables | ||||||

| …are of high quality | ||||||

| Agree, 3-4 | 69 | 72 | 69 | 64 | 68 | .67 |

| ..large selection | ||||||

| Agree, 3-4 | 64 | 63 | 62 | 62 | 69 | .52 |

| …are affordable | ||||||

| Agree, 3-4 | 67 | 69 | 69 | 61 | 62 | .33 |

| Fresh fruit/vegetables summary | ||||||

| High Agreement (9-12) | 38 | 35 | 36 | 41 | 43 | .45 |

| Easy to find healthy food | ||||||

| Agree, 3-4 | 70 | 67 | 71 | 68 | 72 | .70 |

| Store- and Neighborhood-level Characteristics | n=99 | n=39 | n=31 | n=8 | n=21 | |

| Fruit and Vegetable Availability in Store | ||||||

| Pounds (fresh and frozen) | <.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 28 | 10 | 3 | 63 | 86 | |

| 1-18 | 23 | 26 | 39 | 13 | 0 | |

| 19-50 | 22 | 15 | 52 | 0 | 0 | |

| >50 | 26 | 49 | 6 | 25 | 14 | |

| Varieties (fresh, frozen and canned) | <.0001 | |||||

| 0-5 | 27 | 13 | 39 | 0 | 48 | |

| 6-12 | 35 | 18 | 52 | 50 | 38 | |

| >12 | 37 | 69 | 10 | 50 | 14 | |

| Ads and Product Placement in Store | ||||||

| Healthy ads on exterior | 39 | 21 | 61 | 38 | 43 | .005 |

| Healthy ads on interior | 22 | 18 | 40 | 0 | 14 | .04 |

| Unhealthy ads on exterior | 46 | 31 | 94 | 25 | 14 | <.0001 |

| Unhealthy ads on interior | 63 | 49 | 87 | 88 | 48 | .002 |

| Fruits/vegetables visible from entrance | 35 | 49 | 48 | 0 | 5 | .0004 |

| Healthy impulse items at checkout | 63 | 67 | 61 | 38 | 67 | .46 |

| Unhealthy impulse items at checkout | 97 | 95 | 97 | 100 | 100 | .84 |

| Percent of Households in Neighborhood: 185% Below Poverty | 35 (22) | 36 (21) | 34 (23) | 39 (20) | 35 (24) | .97 |

Comparisons of differences across stores types: ANOVA test for means; Chi square test for percentages except Fishers exact test for some due to some cells having expected frequencies <5; (bold if p≤.05)

BMI=body mass index

Twenty-nine percent of participants reported shopping at the store of intercept at least once per day for any reason (ranging from 11% at pharmacies to 38% at corner stores). An additional 44% reported shopping there at least once per week (ranging from 38% in corner stores to 50% at pharmacies). Thirty-three percent of participants reported ever purchasing a fruit or vegetable at the store across all store types. A greater proportion of participants from corner/small grocery stores (43%) and food/gas marts (41%) reported ever purchasing a fruit or vegetable at that store compared to those from dollar stores (12%) and pharmacies (13%). However, there were no significant differences in the proportion of participants across store types that purchased at least one serving of fruit or vegetables at the time of the intercept survey. Only 8% of participants purchased at least one serving of fruits/vegetables at the time of the intercept.

Many participants reported favorable perceptions of the food environment, specifically agreeing that (1) the fresh F&V in the neighborhood of the store were of high quality (69%), (2) a large selection of fresh F&V was available in the neighborhood (64%), and (3) F&V were affordable at the stores in the neighborhood (67%). In addition, 70% of participants perceived that it was easy to find healthy foods in the neighborhood across all store types. There were no statistically significant differences by store type for any of the items individually or summed.

Store-level characteristics are also presented in Table 1. Across all stores, 28% did not have any fresh or frozen fruit or vegetables. Only 3% of food/gas-marts had no fresh or frozen fruit or vegetables, versus 63% of dollar stores and 86% of pharmacies. Most stores had some variety in fresh, frozen, or canned fruits and vegetables with 72% of stores possessing 6 or more varieties. Almost half (46%) of stores had unhealthy exterior food advertising and promotion, with 39% having healthy exterior advertisements. A higher percent of food-gas marts had both healthy and less healthy advertisements compared to other store types. The proportion of dollar stores and pharmacies with fruits and vegetables visible from the entrance was lower than that of corner stores or gas-marts.

Table 2 shows the adjusted associations between store-level characteristics and perceptions of the neighborhood environment. Only the presence of unhealthy interior food and beverage advertisements was significantly associated with perceptions of the neighborhood fruit and vegetable environment (p-value = 0.003). Thus, in stores where unhealthy interior advertisements were located, customers were less likely to broadly perceive the neighborhood as being healthy (i.e., in terms of quality, availability, and affordability of F&V). There were no other significant associations observed.

Table 2.

Associations between perceptions of neighborhood food environment and store characteristics (n=594)

| High agreement that fruits and vegetables are high quality, availability, and affordable | Agreement that it is easy to find healthy food | |

|---|---|---|

| Means (adjusted)1 | Means (adjusted)1 | |

| Fruit and vegetable availability | ||

| Pounds (fresh and frozen) | p=.08 (3df) | p=.42 (3df) |

| 0 | .31 | .67 |

| 1-18 | .36 | .69 |

| 19-50 | .33 | .71 |

| >50 | .48 | .79 |

| Varieties (fresh, frozen and canned) | p=.24 (2df) | p=.54 (2df) |

| 0-5 | .37 | .72 |

| 6-12 | .32 | .68 |

| >12 | .42 | .75 |

| Ads and product placement | ||

| Healthy ads on exterior | p=.46 | p=.95 |

| Yes | .35 | .72 |

| No | .39 | .72 |

| Healthy ads on interior | p=.68 | p=.38 |

| Yes | .35 | .76 |

| No | .38 | .71 |

| Unhealthy ads on exterior | p=.47 | p=.97 |

| Yes | .35 | .72 |

| No | .39 | .72 |

| Unhealthy ads on interior | p=.003 | p=.72 |

| Yes | .32 | .71 |

| No | .46 | .73 |

| Fruits/vegetables visible from entrance | p=.90 | p=.65 |

| Yes | .37 | .70 |

| No | .37 | .73 |

| Healthy impulse items at checkout | p=.86 | p=.65 |

| Yes | .37 | .73 |

| No | .36 | .70 |

| Unhealthy impulse items at checkout | p=.17 | p=.94 |

| Yes | .36 | .72 |

| No | .58 | .70 |

Regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, education, employment, store type and neighborhood-level poverty as fixed effects and store ID as random effect due to nesting of individuals within stores (bold if p≤.05)

df=degrees of freedom

Finally, the relationship between customers’ perceptions of the neighborhood food environment and shopping behaviors are presented in Table 3. When adjusting for covariates, participants who agreed that F&V were high quality, available, and affordable in the store’s neighborhood were more likely to report ever purchasing F&V there (OR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 – 2.6) and had twice the odds of having purchased at least one serving of F&V at the time of intercept (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 – 4.1) compared to participants who did not agree that F&V in the neighborhood were high in quality, availability, and affordability (i.e., “low agreement”). Compared to participants who reported it hard to find healthy foods in the neighborhood, participants who perceived it easy to find healthy foods were also more likely to report ever purchasing fruit and/or vegetables at the store (OR = 1.6, 95% CI 1.0 - 2.4).

Table 3.

Relationship between perceptions of neighborhood food environment and shopping behaviors1

| Shopping frequency | Ever purchased fruit/vegetables at store | Purchased at least one serving of fruit/vegetables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-6/wk vs. <1/wk | ≥1/day vs. <1/wk | Yes vs. No | Yes vs. No | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Agreement that fruits and vegetables are high quality, availability, and affordable (score 0-12) | ||||

| Low Agreement, 0-8 | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| High Agreement, 9-12 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.4) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.6) | 2.2 (1.1, 4.1) |

| Fresh fruit/vegetables are of high quality (0-4) | ||||

| Do not agree, 0-2 | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Agree, 3-4 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.3) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.6) | 2.0 (0.9, 4.9) |

| Large selection of fresh fruit/vegetables (0-4) | ||||

| Do not agree, 0-2 | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Agree, 3-4 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.4) |

| Fruit/vegetables are affordable (0-4) | ||||

| Do not agree, 0-2 | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Agree, 3-4 | 1.2 (0.8, 2.0) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.4) | 1.8 (1.1, 2.7) | 2.6 (1.2, 5.8) |

| Easy to find healthy food | ||||

| Do not agree, 0-2 | ref | ref | ref | Ref |

| Agree, 3-4 | 1.5 (0.9, 2.3) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.8) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.4) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.4) |

Regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, education, employment, store type and neighborhood-level poverty (bold if p≤.05)

OR= odds ratio; CI= confidence interval

Discussion

Our findings support previous findings that customer perceptions of the food environment are associated with food purchasing behaviors.61 Specifically, we found that participants who agreed that fruits and vegetables were available, of high quality, and affordable in the neighborhood where they shopped were also more likely to have purchased a fruit and vegetable from a small or non-traditional food store in that neighborhood. However surprising, healthy store features were, by and large, unrelated to a person’s perceptions of the food environment around the store. Previous research examining perceptions of the food environment have predominantly centered on customer perceptions of their own neighborhood and consumption of fruits and vegetables,8 rather than perceptions of the neighborhood where the store is located. In this study, we were able to examine this relationship as it relates to small and non-traditional food stores and fruit and vegetable purchases.

Our findings address how customer perceptions potentially influence shopping behaviors. For example, if a customer does not have a positive perception of a neighborhood in which a given store is located, then that customer may not seek out healthy food there. This unwillingness to purchase healthy food may be reflected in poor demand, which has been cited as barrier in food environment interventions.62–64 A sustainable supply-demand loop depends on customers having a positive perception of the food environment they encounter.62 In addition, recent findings by Dubowitz et al. have demonstrated that the introduction of a supermarket alone in a community did not improve use of that store and food purchasing behavior; however participants’ perceptions and neighborhood satisfaction may have encouraged changes in shopping behavior.65 Additionally, Cummins et al. examined the impact of a new grocery store observing a positive impact on perceptions of food availability; however it did not lead to increased fruit and vegetable intake.66 These findings support the need to examine the relationship between food environments, customer perceptions, and health behaviors more closely.67

As mentioned earlier, we found no significant relationship between store features (advertisements and product placement) and customer’s perceptions of the neighborhood. This is contrary to our initial hypothesis and counterintuitive to the notion that customer’s perceptions of the neighborhood food environment would be significantly associated with retailer advertising and other store features. However, our results are in line with other published findings that have found that objective aspects of the food environment are often unrelated to consumer perceptions of their food environment44,49 and consistent with another study from the same sample of small and non-traditional food stores, in which store marketing features were largely unrelated to the healthfulness of customer purchases.68 These finding points to the idea that shopping behaviors are complex and a lot of different factors can drive individuals’ shopping decisions and not all factors are related or created equal. Other factors such as neighborhood cleanliness, traffic volume, or safety, all could have influenced a person’s perception of the food environment rather than the store’s actual features.69 In addition, a person’s own bias e.g. preferences and predisposition could also influence how they ultimately perceive their environment.

The lack of relevance of store marketing features to customer psychosocial and behavioral outcomes could be due to several factors. The abundance of food advertising and marketing (much of it for unhealthy products) may result in saturation among customers, so that healthy marketing is overwhelmed by less healthy marketing. Alternatively, it is possible that these small and non-traditional stores -- which tend to be limited in the healthfulness of their offerings, as well as their advertising and promotions – simply may not be representative of the neighborhoods in which they are located. Customers may expect these stores to be unhealthy, even when they have a favorable perception of the neighborhood in which they are located. Within a more healthful neighborhood food environment, customers were more likely to buy fruits and vegetables at the small store. Our results indicate that there may be some discordance between small and non-traditional food store features and the surrounding food environment. More work is needed to examine this effect in future corner store interventions.

Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Our findings should be considered within the context of the study’s limitations. First, data collection was limited to small and non-traditional food stores, excluding large grocery stores and WIC retailers. Secondly, although most participants reported frequently shopping at the store where they were intercepted (at least once per week or more) and 50% lived less than one mile away from the store, they may not have been completely familiar with the surrounding neighborhood they were asked to rate. Third, we did not capture the purpose of each customer’s shopping trip. However, in previous analyses of our sample, it was reported that 75% of customer’s shopped at the store because it was close to their destination.70 Fourth, our customer response rate was 35%. It is possible that participants who consented to participate may have had different kinds of purchases than those who did not consent to participate (and/or different perceptions of the neighborhood environment), but it is difficult to hypothesize the directionality of this potential bias. Also, our analysis does not include perception of the individual store, only perception of the overall food environment. It is possible that customers could have perceived the store differently than the surrounding neighborhood. Lastly, our analysis does not account for customers’ food preferences, predispositions, or awareness/knowledge of the benefits of consuming F&Vs, which could be an unmeasured confounder, affecting both perceptions and behavior.

Strengths of our study include a large sample of objectively assessed F&V purchases, directly observed by trained data collectors at the time of the customer intercept. In addition, data were collected from a wide range of small and non-traditional stores, which have not been included in many studies in the past. We also collected data on perceptions of the neighborhood environment around these stores (rather than the participants’ homes, which has been the focus of previous work in this area).

Implications on Research

Researchers studying food environments have acknowledged that we need a deeper understanding of how people access food, moving beyond basic measures of availability or proximity to supermarkets and/or specific food items. Aspects of the environment including the type of food venue visited, food marketing, and how people perceive their environment can influence food shopping behaviors and interactions within the environment. Moreover, food environments are dynamic and multidimensional spaces that mean different things to different people. And when considering a social-ecological approach, which characterizes the relationship between people and their environments, there are many forces that can shape human behavior.54 In the area of food shopping, the physical environment has received a lot of attention, however, other factors including a person’s perceptions, preferences, and social constructs can play a role and warrant consideration. In this study, we have examined how customers’ perceptions were related to their purchasing of fruits and vegetables. In future research, it may be important to consider customers’ awareness and perceptions of the food environment if the objective of an intervention, for instance, is to improve fruit and vegetable purchasing in a designated community. Hence, perceptions of the surrounding community food environment might contribute to a store’s success in selling healthy food. These perceptions may also be independent of the store’s features, which were not associated with customers’ perceptions of the neighborhood food environment in our study. Despite less healthful marketing features at a store, customers’ environmental cues may be derived from other factors, such as neighborhood aesthetics, perceived safety, and/or socio-economic status of residents.

Conclusions

Findings suggest there may be an association between how individuals perceive the availability of F&V in the environment and their F&V purchasing behaviors at small and non-traditional food stores like corner stores, gas-marts, dollar stores, and pharmacies. Findings also support previous studies indicating that certain neighborhoods draw people who seek out healthy food based on perceived access to fruits and vegetables. Future small store interventions might need to take into account the surrounding features of the food environment, because customers’ perceptions of the neighborhood may be a primer of whether or not they purchase healthy food there.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Minneapolis Health Department for their support and expertise working with local small food stores. We would also like to acknowledge the large data acquisition and data management team, most especially Stacey Moe, William Baker, and Pamela Carr-Manthe. Finally, we thank the participants of this study.

Financial Support:

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (M.N.L. grant number R01DK104348) and the Global Obesity Prevention Center (GOPC) at Johns Hopkins, which is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (M.N.L, grant number U54HD070725). Support for Dr. Caspi was provided by the National Cancer Institute, Cancer Related Health Disparities Education and Career Development Program (grant number R25CA163184). NIH grant UL1TR000114 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) supported data management. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Funding agencies had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Timothy L. Barnes, Email: timothy.barnes@childensmn.org, tlbarnes@umn.edu.

Kathleen Lenk, Email: lenk@umn.edu.

Caitlin E. Caspi, Email: cecaspi@umn.edu.

Darin J. Erickson, Email: erick232@umn.edu.

Melissa N. Laska, Email: mnlaska@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336(16):1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borgi L, Muraki I, Satija A, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Forman JP. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and the Incidence of Hypertension in Three Prospective Cohort Studies. Hypertension 2016;67(2):288–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96(21):1577–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He FJ, Nowson CA, MacGregor GA. Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet 2006;367(9507):320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014;349:g4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition December 2015. 2015; Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. 2015.

- 7.Key TJ. Fruit and vegetables and cancer risk. Br J Cancer 2011;104(1):6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place 2012;18(5):1172–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspi CE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Adamkiewicz G, Sorensen G. The relationship between diet and perceived and objective access to supermarkets among low-income housing residents. SocSciMed 2012;75(7):1254–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morland K, Wing S, Diez RA. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. AmJPublic Health 2002;92(11):1761–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose D, Richards R. Food store access and household fruit and vegetable use among participants in the US Food Stamp Program. Public Health Nutr 2004;7(8):1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenk SN, Lachance LL, Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Kannan S, Ridella W. Neighborhood retail food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in a multiethnic urban population. AmJHealth Promot 2009;23(4):255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Kaufman JS, Jones SJ. Proximity of supermarkets is positively associated with diet quality index for pregnancy. PrevMed 2004;39(5):869–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodor JN, Rice JC, Farley TA, Swalm CM, Rose D. The association between obesity and urban food environments. JUrban Health 2010;87(5):771–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Angelo H, Suratkar S, Song HJ, Stauffer E, Gittelsohn J. Access to food source and food source use are associated with healthy and unhealthy food-purchasing behaviours among low-income African-American adults in Baltimore City. Public Health Nutr 2011;14(9):1632–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. PrevChronicDis 2012;9:E59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell LM, Slater S, Mirtcheva D, Bao Y, Chaloupka FJ. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. PrevMed 2007;44(3):189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lent MR, Vander Veur S, Mallya G, et al. Corner store purchases made by adults, adolescents and children: items, nutritional characteristics and amount spent. Public Health Nutr 2015;18(9):1706–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiszko K, Cantor J, Abrams C, et al. Corner Store Purchases in a Low-Income Urban Community in NYC. J Community Health 2015;40(6):1084–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitts SB, Bringolf KR, Lawton KK, et al. Formative evaluation for a healthy corner store initiative in Pitt County, North Carolina: assessing the rural food environment, part 1. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruff RR, Akhund A, Adjoian T. Small Convenience Stores and the Local Food Environment: An Analysis of Resident Shopping Behavior Using Multilevel Modeling. AmJHealth Promot 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borradaile KE, Sherman S, Vander Veur SS, et al. Snacking in children: the role of urban corner stores. Pediatrics 2009;124(5):1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dannefer R, Williams DA, Baronberg S, Silver L. Healthy bodegas: increasing and promoting healthy foods at corner stores in New York City. Am J Public Health 2012;102(10):e27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern D, Ng SW, Popkin BM. The Nutrient Content of U.S. Household Food Purchases by Store Type. Am J Prev Med 2016;50(2):180–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adjoian T, Dannefer R, Sacks R, Van Wye G. Comparing sugary drinks in the food retail environment in six NYC neighborhoods. J Community Health 2014;39(2):327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laska MN, Caspi CE, Pelletier JE, Friebur R, Harnack LJ. Lack of Healthy Food in Small-Size to Mid-Size Retailers Participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, 2014. PrevChronicDis 2015;12:E135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caspi CE, Pelletier JE, Harnack L, Erickson DJ, Laska MN. Differences in healthy food supply and stocking practices between small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Public Health Nutr 2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gantner LA, Olson CM, Frongillo EA, Wells NM. Prevalence of Nontraditional Food Stores and Distance to Healthy Foods in a Rural Food Environment. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 2011;6:279–293. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez SW. The US Food Marketing System: Recent Developments, 1997-2006. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture Economic Research ServiceEconomic Research Report Number 42 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Racine EF, Batada A, Solomon CA, Story M. Availability of Foods and Beverages in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Authorized Dollar Stores in a Region of North Carolina. J Acad Nutr Diet 2016;116(10):1613–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lent MR, Vander Veur SS, McCoy TA, et al. A randomized controlled study of a healthy corner store initiative on the purchases of urban, low-income youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22(12):2494–2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laska MN, Borradaile KE, Tester J, Foster GD, Gittelsohn J. Healthy food availability in small urban food stores: a comparison of four US cities. Public Health Nutr 2010;13(7):1031–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caspi CE, Lenk K, Pelletier JE, et al. Food and beverage purchases in corner stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Public Health Nutr 2016:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morland KB, Evenson KR. Obesity prevalence and the local food environment. Health Place 2009;15(2):491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morland K, ez Roux AV, Wing S. Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. AmJPrevMed 2006;30(4):333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wall MM, Larson NI, Forsyth A, et al. Patterns of obesogenic neighborhood features and adolescent weight: a comparison of statistical approaches. AmJPrevMed 2012;42(5):e65–e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almy J, Wootan M. Temptation At Checkout, The Food Industry’s Sneaky Strategy for Selling More. Center for Science in the Public Interest 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes TL, Pelletier JE, Erickson DJ, Caspi CE, Harnack LJ, Laska MN. Healthfulness of Foods Advertised in Small and Nontraditional Urban Stores in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2016;13:E153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebauer H, Laska MN. Convenience stores surrounding urban schools: an assessment of healthy food availability, advertising, and product placement. JUrban Health 2011;88(4):616–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barker D, Quinn C, Rimkus L, Mineart C, Zenk S, Chaloupka F. Availability of Healthy Food Products at Check-ou Nationwide, 2010–2012. A BTG Research Brief. Chicago, IL: Bridging the Gap Program, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langellier BA, Garza JR, Prelip ML, Glik D, Brookmeyer R, Ortega AN. Corner Store Inventories, Purchases, and Strategies for Intervention: A Review of the Literature. CalifJ Health Promot 2013;11(3):1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paek HJ, Oh HJ, Jung Y, et al. Assessment of a healthy corner store program (FIT Store) in low-income, urban, and ethnically diverse neighborhoods in Michigan. Fam Community Health 2014;37(1):86–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laska MN, Pelletier JE. Minimum Stocking Levels and Marketing Strategies of Healthful Foods for Small Retail Food Stores. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams LK, Thornton L, Ball K, Crawford D. Is the objective food environment associated with perceptions of the food environment? Public Health Nutr 2011:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inglis V, Ball K, Crawford D. Socioeconomic variations in women’s diets: what is the role of perceptions of the local food environment? JEpidemiolCommunity Health 2008;62(3):191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blitstein JL, Snider J, Evans WD. Perceptions of the food shopping environment are associated with greater consumption of fruits and vegetables. Public Health Nutr 2012;15(6):1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnes TL, Bell BA, Freedman DA, Colabianchi N, Liese AD. Do people really know what food retailers exist in their neighborhood? Examining GIS-based and perceived presence of retail food outlets in an eight-county region of South Carolina. SpatSpatiotemporalEpidemiol 2015;13:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnes TL, Freedman DA, Bell BA, Colabianchi N, Liese AD. Geographic measures of retail food outlets and perceived availability of healthy foods in neighbourhoods. Public Health Nutr 2015:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gustafson AA, Sharkey J, Samuel-Hodge CD, et al. Perceived and objective measures of the food store environment and the association with weight and diet among low-income women in North Carolina. PublicHealthNutr 2011:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams L, Ball K, Crawford D. Why do some socioeconomically disadvantaged women eat better than others? An investigation of the personal, social and environmental correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption. Appetite 2010;55(3):441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dubowitz T, Zenk SN, Ghosh-Dastidar B, et al. Healthy food access for urban food desert residents: examination of the food environment, food purchasing practices, diet and BMI. Public Health Nutr 2015;18(12):2220–2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DiSantis KI, Hillier A, Holaday R, Kumanyika S. Why do you shop there? A mixed methods study mapping household food shopping patterns onto weekly routines of black women. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cannuscio CC, Tappe K, Hillier A, Buttenheim A, Karpyn A, Glanz K. Urban food environments and residents’ shopping behaviors. Am J PrevMed 2013;45(5):606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cannuscio CC, Hillier A, Karpyn A, Glanz K. The social dynamics of healthy food shopping and store choice in an urban environment. Soc Sci Med 2014;122:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.SFO. Minneapolis Staples Foods Ordinance. 2015.

- 56.Pelletier JE, Caspi CE, Schreiber LR, Erickson DJ, Harnack L, Laska MN. Successful customer intercept interview recruitment outside small and midsize urban food retailers. BMC Public Health 2016;16(1):1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams LK, Thornton L, Crawford D, Ball K. Perceived quality and availability of fruit and vegetables are associated with perceptions of fruit and vegetable affordability among socio-economically disadvantaged women. Public Health Nutr 2012;15(7):1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore LV, ez Roux AV, Brines S. Comparing Perception-Based and Geographic Information System (GIS)-based characterizations of the local food environment. JUrbanHealth 2008;85(2):206–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moore LV, ez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR Jr. Associations of the local food environment with diet quality--a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. AmJEpidemiol 2008;167(8):917–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.United States Census Bureau. 2009-2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Data Profiles. 2013; https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2013/. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- 61.Graham DJ, Pelletier JE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lust K, Laska MN. Perceived social-ecological factors associated with fruit and vegetable purchasing, preparation, and consumption among young adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113(10):1366–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gittelsohn J, Laska MN, Karpyn A, Klingler K, Ayala GX. Lessons learned from small store programs to increase healthy food access. Am J Health Behav 2014;38(2):307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andreyeva T, Middleton AE, Long MW, Luedicke J, Schwartz MB. Food retailer practices, attitudes and beliefs about the supply of healthy foods. Public Health Nutr 2011;14(6):1024–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ayala GX, Laska MN, Zenk SN, et al. Stocking characteristics and perceived increases in sales among small food store managers/owners associated with the introduction of new food products approved by the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Public Health Nutr 2012;15(9):1771–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubowitz T, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Cohen DA, et al. Diet And Perceptions Change With Supermarket Introduction In A Food Desert, But Not Because Of Supermarket Use. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1858–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cummins S, Flint E, Matthews SA. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(2):283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Green SH, Glanz K. Development of the Perceived Nutrition Environment Measures Survey. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(1):50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caspi C, Lenk K, Pelletier J, et al. Association between store food environment and customer purchases in small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jilcott SB, Laraia BA, Evenson KR, Ammerman AS. Perceptions of the community food environment and related influences on food choice among midlife women residing in rural and urban areas: a qualitative analysis. Women Health 2009;49(2-3):164–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lenk KM, Caspi CE, Harnack L, Laska MN. Customer Characteristics and Shopping Patterns Associated with Healthy and Unhealthy Purchases at Small and Non-traditional Food Stores. J Community Health 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]