Abstract

Objectives

The diagnosis and treatment of acute leukaemia (AL) affect physical, psychosocial and existential functioning. Long-lasting treatment periods with impaired immune system, hygienic and social restrictions challenge patient well-being and rehabilitation as compared with other individuals with cancer. This study elucidates how AL patients, treated with curative intent in an outpatient setting, assess their physical, psychosocial and existential capability during and following treatment, and furthermore reports on the health initiatives offered to support their rehabilitation.

Design, setting, participants and interventions

We conducted qualitative, semi-structured individual interviews with 16 AL patients, 6 months after end of treatment in the patients’ homes. This was the final interview, in a line of three, carried out as part of a larger qualitative study.

Results

The data were analysed thematically through an inductive ongoing process consisting of four steps. The final step, selective coding, resulted in the three categories: physical activity, mental well-being and social activity. None of the patients were satisfied with their physical capability at the time of interview and experienced substantial impairment of functional capabilities. All patients struggled with anxiety and expressed a need for continuous progress in treatment and well-being to feel safe. It took an unexpected large effort to regain a meaningful social life, and patients still had to prioritise activities.

Conclusions

AL patients suffered physically, psychologically and existentially throughout their illness trajectory. Rehabilitation initiatives deriving from the healthcare system and municipalities held room for improvement. Future programmes should pay attention to the contextual changes of treatment of this patient group and individuals’ changing needs and motivation of physical exercise.

Keywords: rehabilitation, acute leukemia, everyday life, qualitative study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A relatively small number of participants may challenge generalisation to the wider population of individuals with haematological cancer.

The patients showed a high degree of self-preservation instinct during the illness trajectory, which may indicate a selection bias.

The theoretical framework of rehabilitation may strengthen the possibility of analytical generalisation.

Introduction

Patients with acute leukaemia (AL) undergo extraordinary long periods of intensive treatment with high susceptibility to sudden and dramatic changes in their health condition and prognosis.1 Impairment of the immune system necessitates substantial hygienic and social restrictions. However, during the last decade, a paradigm shift in the treatment of these severely immune insufficient patients has occurred. The patients who were formerly isolated at the hospital during their highly intensive treatment are now managed in the outpatient setting (OPS) while concurrently living at home. Rehabilitation needs of the patients and rehabilitation offers by the healthcare system are challenged by these organisational changes. However, little clinical or research attention has been paid to rehabilitation and survivorship care for this specific group of immune insufficient individuals with haematological cancer managed in an OPS.

In this paper, the concept of rehabilitation refers to specific initiatives and efforts by health professionals but is also an analytical concept for describing the process in which the patients reframe a sense of self.2

The existing knowledge underlines beneficial effects of rehabilitation to individuals with cancer. From a few studies, we know that physical exercise is feasible and safe for AL inpatients, even those with critical cytopenia. Beneficial effects on physical performance, fatigue and quality of life have been shown.3–9 As an example, supervised exercise and health counselling intervention for patients with AL during outpatient management showed physical, functional, psychosocial and symptom benefits.8 Patients undergoing allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) due to haematological malignancies have also shown significant benefit from exercise interventions without reports of negative effects.9

Health-related quality of life of individuals with haematological cancer is lowered mainly due to reduced role functioning, insomnia and fatigue.10 11 Unmet needs of rehabilitation are strongly associated with impaired quality of life for individuals with cancer in general.12 Psychological counselling, physical rehabilitation, sexual and financial support and practical help have been found to be important, but needs vary with age, sex and cancer diagnosis.13 14

Summing up, the existing knowledge underlines the beneficial effects of rehabilitation to patients with AL. However, the rapid changes of treatment setting, patient population and lack of knowledge of existing evidence may leave patients with unmet needs and functional impairment. Knowledge about patients’ experiences and expectations from the very special context of outpatient management may have the potential to improve well-being of an increasing and still older group of intensively treated patients.

Based on patient interviews, this paper elucidates how patients with AL treated with curative aim assess their physical, psychosocial and existential capability during and following treatment and health initiatives supporting their rehabilitation.

Material and methods

Design

The material derives from individual, semi-structured interviews with 16 patients, 6 months after end of treatment. This type of interview was deemed suitable to access and explore patient experience in an open manner to allow for patients to add their own perspectives to the interviewer’s agenda. These interviews were the third and final interview, conducted as part of a larger qualitative study with the overall aim of exploring the OPS as a context of intensive cancer treatment.15 16 We combined participant observation in the OPS), individual patient interviews, and group or individual interviews with their relatives. Patients were consecutively invited by and gave consent to the first author, LØJ, who conducted the interviews. LØJ presented herself as a PhD student and young medical doctor with previous experience in the department.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted based on a thematic interview guide.15 The first topic was ‘impact on everyday life practices’ where rehabilitation issues were addressed by questions such as ‘Try to describe your present physical capability and how you reached that level’. The question was repeated for psychosocial and existential well-being. There was 1 main question to each topic, and depending on the patient’s answers, 3–18 additional questions to cover the topic sufficiently. The second topic, ‘the home’, explored daily life at home and the roles of the family, whereas the third topic ‘hygiene’ addressed the impact of intense hygiene requirements.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the research design.

Participants and interviews

Participants were Danish speaking patients with AL intensively treated with a curative aim. All were managed in the OPS, ‘the Home Unit’ at the Department of Haematology, Odense University Hospital (OUH) and subsequently followed in the outpatient clinic at OUH or at the National University Hospital, Copenhagen or at Aarhus University Hospital if allogenically transplanted.15

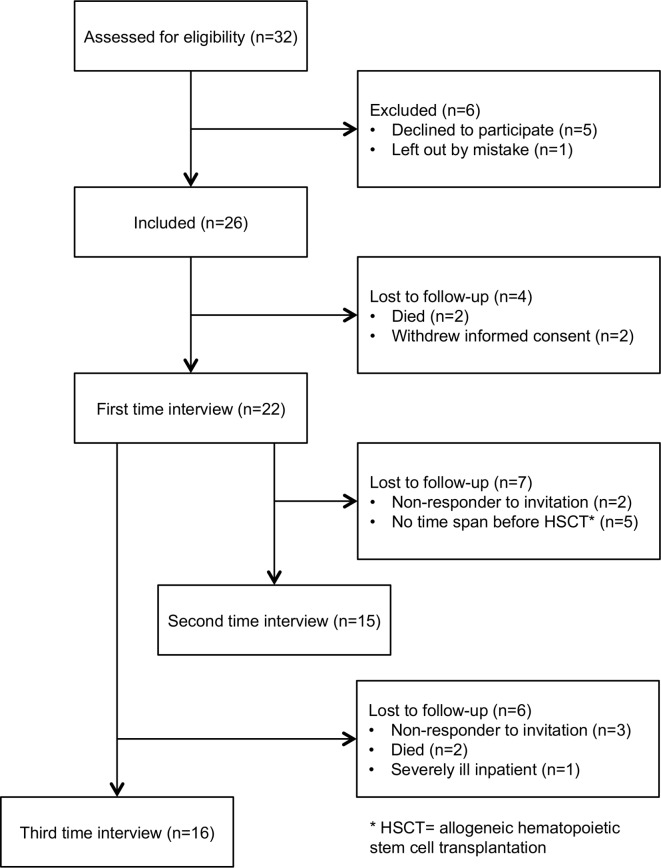

Twenty-six patients were included from May 2013 to August 2014, and out of this group, 16 took part in this third interview, 6 months after end of treatment (figure 1). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics.

Figure 1.

Enrolment of patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants (n=16)

| Sample characteristics, third interview | Description |

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (56%) |

| Female | 7 (44%) |

| Age (years) | Mean 55.1; range up to 75) |

| <60 | 8 (50%) |

| ≥60 | 8 (50%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or common-law relationship | 13 (81%) |

| Single/divorced | 3 (19%) |

| Education | |

| Unskilled workers | 2 (12%) |

| Skilled workers | 10 (63%) |

| Further education | 4 (25%) |

| Diagnosis* | |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) | 11 (69%) (3 relapse) |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia in myeloid blast crisis (CML) | 1 (6%) |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) | 1 (6%) |

| Refractory anaemia with excess blasts (RAEB) | 1 (6%) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) | 2 (13%) |

| Time from diagnosis to third interview (weeks) | Mean 51.9; range 40–72 |

| Treatment status | |

| Outpatient Clinic follow-up, Odense University Hospital | 3 (19%) |

| Allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, National University Hospital, Copenhagen or Aarhus University Hospital | 10 (62%) |

| Second line therapy, Odense University Hospital | 3 (19%) |

The CML, CMML and RAEB special leukaemia diagnoses, which are chronic diseases, but often turn into acute leukaemia after a short time. Therefore, they received treatment equivalent to acute leukaemia patients’ regiments and were handled identically to them.

The interviews were conducted in the patients’ home and lasted from 40 to 115 min (mean 68 min). With permission, all interviews were digitally recorded.

Context for rehabilitation

Rehabilitation has previously been understood as a practice related to the post-treatment life of patients, but the facilities and practices of the hospital during inpatient and outpatient management may be considered a context of rehabilitation of patients with AL. In addition, non-hospital settings may be part of the rehabilitation.

The course of treatment for newly diagnosed patients with AL who are candidates for curative intended chemotherapy contains both inpatient and outpatient periods. The latter where the patients, during periods with severe haematological cytopenia, stay at home and appear at follow-up visits every second day.15

The OPS was situated next to the haematological department, OUH, where all the patients could use the fitness facilities located there. A physiotherapist was present twice a week to instruct the patients.

Before receiving the transplant, patients were instructed in some simple exercises by a physiotherapist. Furthermore, all patients had an exercise-bike in their bedroom during periods of isolation at the hospital.

In addition to physical exercise, patients could, at any time, ask for a referral for individual advice by a physiotherapist, a psychologist, a chaplain or a medical social worker at the department. Furthermore, psychologists from The Danish Cancer Society were available to patients and relatives in facilities at the hospital.

In Denmark, the overall responsibility of rehabilitation is located at the local municipality level (98 municipalities/5.6 million inhabitants). Due to different demographics, staff and geography of the municipalities, patients meet different offers and knowledge about their disease.17

Theoretical framework and analysis

The study was based on the WHO definition of rehabilitation,18 but simultaneously acknowledged that rehabilitation formed an analytical approach to the physical, psychosocial and existential challenges facing the patients with AL, and was not a structural or organisational intervention as such. This paper aims to study the configuration of rehabilitation needs as experienced by patients with AL and to draw attention to possible contextual factors that should be taken into account in future programmes. To further support our analytical exploration, the theoretical framework included International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) pointing out the dynamic interaction of health condition, body function and structure, activity, participation, and personal as well as environmental factors.19

The data were analysed thematically through an inductive ongoing process of four steps inspired by Miles et al.20 Step 1: the interviews were transcribed by a secretary and read several times by LØJ to gain an overall understanding of the material. Step 2: specific paragraphs were identified as the content and context related to each other and the study aim. Step 3: descriptive codes were produced and assigned. Step 4: through selective coding the text was condensed into categories. The group of authors discussed the contents and interpretation of data throughout the process.

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from all individual study participants. The study was approved by The Regional Scientific Ethical Committees for Southern Denmark (S-20122000 86), the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. no. 2008-58-0035) and the Department of Haematology, OUH. The first author had no professional medical interaction with the participants during the study period. We carefully recognise that participation in research while undergoing treatment for a serious illness puts strain on patients.

Results

Patients did not use the word ‘rehabilitation’ about the process of regaining physical, mental and social functioning. Rehabilitation was therefore an analytical condensation of the AL patients’ assessments of their capability and experiences of supportive initiatives. Subcategories of physical activity, mental well-being and social activity were constructed and will be described separately in the following, although strongly interrelated as conceptualised by WHO and in the ICF-model.19 Existential reflections and challenges emerged during interviews.

Reorganisation of the everyday life practices was a first step for many of the patients. This process began when being discharged from hospital the first time and continued after end of treatment. They described how they had lacked the energy to participate in a full day’s programme, and for example had escalated activities from twice a week to every second day and from one to 5 hours. Their pace was still slow through all activities, and a nap in the afternoon was often needed. They preferred projects without a deadline. Limited house-keeping tasks, such as cutting the grass or vacuuming the house which would have posed no problem prior to the onset of illness were now ‘physically demanding’. This challenged them substantially and greatly impacted their daily lives and psychosocial well-being. They had expected this during treatment, but 6 months after end of treatment, the patients had expected to be ‘back to normal’.

Physical activity

Nearly all patients reported that they went for walks, but the intensity, the distance and how often varied between patients and times during the illness trajectory. Some patients with neuropathy in the feet could only walk brief distances, whereas others walked for 1½ hour. The simple exercises, including the use of elastic exercise bands, as instructed at OUH were used by many patients.

I’ve only made those exercises and I feel a little – guilty about it because they said, You should just (walk) half an hour round the neighbourhood. [] I’m a little afraid to fall. The energy level is also crucial. But now for example to day I would be able to do it. I would be able to walk half an hour. But then tomorrow maybe I’m just as limp as a dishrag. (Patient 10)

Referral from the hospital to the municipality for rehabilitation services was not systematic. The service offered by the municipalities comprised group training with other types of patients, 1 hour twice a week for six to twelve weeks. All the participants of this study experienced being the only patient with AL/HSCT. By the end of the course of training many were told that they performed too well to continue in the group. The patients described a lack of enthusiasm and competences by the healthcare professionals in the municipalities.

After concluding chemotherapy, a handful of patients exercised more intensively in a fitness centre; did bike rides of 50 kilometers, swims of 1000 metres or three to four kilometres of running. They wanted to regain their usual physical strength and fitness but also aimed to be prepared if the AL relapsed.

So I was active. [] But I also think I had constantly in my mind – if it – my leukaemia comes back, I’ll fucking be in good shape, right. (Patient 18)

None of the patients were satisfied with their physical status 6 months after the end of treatment or with being less capable than expected. In hindsight they reflected that it had been too easy to ‘escape’ the physiotherapist during hospitalisation. They did not remember having been encouraged to be physically active when referred to the OPS. In the first interviews15 the patients described how they prioritised socialising with fellow patients in the OPS to the detriment of physical training. Still, they did not participate in organised training but were more active through all the unnoticed activities at home, such as doing the laundry, the dishes or walking the stairs.15 However, activities that were part of their everyday life were not perceived by patients as exercise.

The outcome of training programme offered by the municipality was experienced by the patients as low, and they often performed too well to continue the programme. Being evaluated in this way seemed counterproductive to their motivation to continue training and produced dissatisfaction with their own physical capability at the time of the last interview. The lack of physical capability still prevented the patients from engaging in everyday life activities as they used to and wanted to.

Mental well-being

The treatment and the physical capability strongly influenced the mental well-being of the patients. When not feeling better or when physical symptoms caused uncertainty the patients felt challenged.

But I think psychologically or mentally we are pretty strong. That’s not a problem. That I can recognise clearly. The only time I got a knock, was when the one kidney stopped working. There I thought damn, what is brewing now. (Patient 19)

Anxiety was always present but seldom shown, patients reported. Small things like a spot on the skin initiated a flow of thoughts: graft versus host disease – AL relapse – death. One way to avoid these thoughts was to be occupied with practical tasks and another way was to talk to family members or friends. All patients used these coping strategies to a varying extent, and furthermore they talked to fellow-patients, when meeting in the OPS.

AL had challenged their invulnerability and sense of self, which was usually shaped by work or social activities. Therefore, many patients raised the existential question: ‘Who am I – besides being a leukaemia patient?’

Principally you are a lot because of you training and the background you have and what you do. (Patient 23)

Patients had perceived that being cured was the end of the illness trajectory. The stepwise prolongation experienced by everyone was psychologically draining. Furthermore, it was hard never to be given a ‘cured-date’. As an alternative some patients made their own goals for when to view themselves as cured.

Your status gets chronic. I have actually not spotted exactly what you get, but I have certainly been told that I do not get a fit-for-duty certificate. So I just had, in a different way, to define to myself when I’m recovered. And I am when I run my next half marathon. (Patient 25)

Few patients had consulted a psychologist during the illness trajectory. The majority experienced no need to, especially not in the beginning when survival and physical issues had priority. Later, it was a barrier to seek counselling knowing they would have to describe their illness trajectory once again.

Mental well-being was influenced by flow in treatment and physical capability. Most patients addressed the mental challenges by talking to family and friends, which was also reflected by the fact that few patients had contacted a psychologist.

Social activity

As previously described the social life of patients suffered while being inpatients, while outpatient management allowed for more time spent together with fellow patients. This type of community became an important and highly valued part of their social life.15

The difference between friends and acquaintances became more apparent as time went by. Losing contact with persons previously counted as friends was a mental strain. As the trajectory proceeded patients wanted the conversation to turn away from illness and treatment on to everyday things and the future.

When we get together with friends, then there is a lot of talk about my illness. And that’s fair enough, so now let’s talk about it and then move on. I also need some input, from the outside. (Patient 25)

The treatment precautions during periods with severe haematological neutropenia meant that patients only saw a few people at a time and that nearly all social activity took place at home or at the hospital. Returning to a more regular social life after end of treatment was overwhelming and unexpectedly demanding.

I have also begun to go and watch a football match and stuff even though that it’s not my interest at all. But it is to learn to get along in those large gatherings. That was enormously difficult I think. All that noise I had to get used to. It is difficult when you have been just inside the house without anything. (Patient 18)

Six months after end of treatment the energy level of patients was still impaired. Patients thus had to choose for themselves what to participate in, and social activities were in competition with practical tasks, physical activity and work.

The patients described how it was unexpectedly demanding to regain a meaningful social life. None of the patients experienced or expected that social life had the attention of professional intervention.

Discussion

Six months after the end of treatment patients with AL were dissatisfied with their physical, psychological and social capability. The rehabilitation support during all phases of treatment including HSCT and the following phase of recovery were experienced as non-existing, minimal or inadequate.

Our results from the interviews conducted during earlier treatment phases showed that maintaining everyday life was highly prioritised by patients as well as spouses.15 16 In line with that, patients reported that they did not exercise as much as they wanted to. In contrast with the evidence, a long haematological tradition of avoiding physical training during periods of cytopenia may still be in practice.8 21 Patients did not recall professionals’ attention to physical activity during the course of treatment. At the same time they describe having refused the physiotherapist’s training offer and prioritised the social engagement while at the OPS.15 Less contact with healthcare professionals during outpatient management may be another important barrier. Our third interview thereby adds that the patients’ attitude towards training changed substantially from having no motivation to feeling highly motivated after end of treatment. According to the patients the municipalities did not offer training courses matching these needs – at that time. Some patients were informed that they were performing too well to participate. Perhaps because they did not suffer from any specific disability but were very generally weakened. The termination of the training course contrasted their own perception of lacking physical capabilities to participate in everyday activities. Individual needs assessment based on the ICF-model including ‘activity’ and ‘participation’ could assist future patients and responsible practitioners to better understand patients’ functional level and motivation.19

It is relevant to consider that there is a difference between the patients’ attitudes and concrete actions regarding physical training during treatment. In the late modern society, patients are expected to take individual responsibility for their own health and health behaviour – such as physical exercise, healthy food and so on.22 It may be experienced as stigmatising to the patients not to satisfy such expectations. This could, as a context for blaming the healthcare system for a lack of attention, be moving the responsibility away from the self and to the system.22 23

In line with the dynamic of the ICF-model the treatment and the physical capability strongly influenced the mental well-being of the patients and vice versa.19 Few patients called for easier access to psychologists but the majority found no need since they experienced support from family, friends and other healthcare professionals. This is in line with a questionnaire study among 132 mixed haematological and oncological patients.24 Internationally, systematic needs assessment has been recommended as part of routine cancer care to uncover substantial needs for professional support that would otherwise not be addressed.18 However, none of the patients in our study have had such a consultation. Another explanation to the sparse demand for psychological support may be that the weakest patients declined to participate in the study, had left, or that demanding existential problems surface later.

The patients had to prioritise caring for themselves even though it sometimes caused emotional limbo, as described in a previous focus group interview study of mixed individuals with cancer.25 Social reintegration unexpectedly required an effort, and they had to challenge themselves step-by-step. None seemed to expect professional help and no one stated that they should have been warned of the social challenges. This gives the impression that the patients made no connection between their social life and the possibility of professional support, e.g. as part of rehabilitation in line with the definition18 and ICF-model.19

Strength and limitations

The study design with a relatively small number of participants limits generalisation to the wider population of individuals with haematological cancer. The majority of patients received a HSCT as the final treatment entity, and we were not able to differentiate our analysis in this regard. The patients showed a high degree of self-preservation instinct during the illness trajectory, which may indicate a selection bias. However, the theoretical framework of rehabilitation may strengthen the possibility of analytical generalisation. Using the dynamic ICF-model as basis of the data analysis, the focus was on physical, psychological and social functioning of the body, activity and participation together with health-related and environmental factors. In a rehabilitation perspective of this specific group of individuals with cancer, 6 months after intensive treatment seems a short time. Additional data after 1 year or longer may show other aspects and perspectives on for example, late mental or existential problems that cause other needs for rehabilitation.

Perspectives

This study has several implications for future patients. The patients wanted the rehabilitation process to begin shortly after the start of treatment. This is in line with all rehabilitation recommendations18 19 and highlights the need for focus on maintaining instead of catching up lost capabilities.

The need for continuous motivation by healthcare professionals was underlined. Patients’ understanding of and focus on the importance of physical activity for future performance are important, especially on days with exhausting symptoms or bad mood. Even minor everyday activities like the change of linen counter loss of muscle and impaired physical capability.8 Simple exercises could be introduced shortly after the start of treatment and be supervised through treatment including the OPS. Perhaps it is possible to couple these with social engagement with fellow patients. This may support continuity and activities across different hospitals, home and municipality initiatives improving well-being and quality of life among patients.

Psychological counselling may support some patients, but healthcare professionals should be aware of patient barriers rising from the need to ‘tell their story’ once more.

A review of the evidence for the treatment-initiated precautions can lead to improved patients’ participation in role functioning, family and social life. Furthermore this study suggests timely preparation of patient and family members for them to understand that regaining a normal social life after end of treatment will be another demanding phase.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study contribute to our understanding of how outpatients with AL treated with curative intension, including HSCT, experience rehabilitation up to 6 months after end of treatment.

None of the patients were satisfied with their physical capability 6 months after end of treatment. They managed to be physically active through daily tasks and had not experienced being offered an exercise programme matching their needs at the end of treatment when their motivation for being physically active arose. Psychologically the patients struggled with anxiety with regards to infections or relapse, and their perceived needs for progress in the treatment and in everyday functioning to feel well. Talking to family and friends was experienced as a good way of addressing psychological challenges. The precautions stipulated by the hospitals restricted social life and it unexpectedly demanded an effort by the patients to regain a meaningful social life.

Room for improvement of rehabilitation initiatives, from both the healthcare system and the municipalities, has been identified. Regular needs assessment should be used to understand changes in health and motivation during the illness trajectory. Healthcare professionals should remember that 6 months after end of treatment is too early to expect full recovery of many everyday basic skills. For the benefit of the patients, information about the rehabilitation process can be given up front, but must be addressed continuously.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the patients who participated in the study for their valuable contributions during a difficult period of their lives.

Footnotes

Contributors: LØJ participated in the design of the study, carried out the interviews, analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. LF participated in the design of the study and in the discussion of the analysis and the results. She also critically revised the manuscript. CM participated in the discussion of the analysis and the results. He also critically revised the manuscript. MH participated in the design of the study and in the discussion of the analysis and the results. She also critically revised the manuscript. DH participated in the design of the study and in the discussion of the analysis and the results. She also critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the University of Southern Denmark, DKK 400.000, the Region of Southern Denmark, DKK 500.000, The Danish Cancer Society, DKK 465.000, the Anders Hasselbalch Foundation, DKK 20.000, the Family Hede Nielsen Foundation, DKK 25.000 and the joint research pool between National University Hospital and Odense University Hospital supporting the highly specialised functions, DKK 40.000. The National Research Center of Cancer Rehabilitation, University of Southern Denmark is partly funded by the Danish Cancer Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Walter RB, Taylor LR, Gardner KM, et al. Outpatient management following intensive induction or salvage chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2013;11:571–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Messinger SD. Getting past the accident: explosive devices, limb loss, and refashioning a life in a military medical center. Med Anthropol Q 2010;24:281–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elter T, Stipanov M, Heuser E, et al. Is physical exercise possible in patients with critical cytopenia undergoing intensive chemotherapy for acute leukaemia or aggressive lymphoma? Int J Hematol 2009;90:199–204. 10.1007/s12185-009-0376-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dimeo F, Schwartz S, Fietz T, et al. Effects of endurance training on the physical performance of patients with hematological malignancies during chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer 2003;11:623–8. 10.1007/s00520-003-0512-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Battaglini CL, Hackney AC, Garcia R, et al. The effects of an exercise program in leukemia patients. Integr Cancer Ther 2009;8:130–8. 10.1177/1534735409334266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alibhai SMH, O’Neill S, Fisher-Schlombs K, et al. A clinical trial of supervised exercise for adult inpatients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) undergoing induction chemotherapy. Leuk Res 2012;36:1255–61. 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alibhai SMH, Durbano S, Breunis H, et al. A phase II exercise randomized controlled trial for patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing induction chemotherapy. Leuk Res 2015:S0145-2126(15)30365-9 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jarden M, Adamsen L, Kjeldsen L, et al. The emerging role of exercise and health counseling in patients with acute leukemia undergoing chemotherapy during outpatient management. Leuk Res 2013;37:155–61. 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiskemann J, Huber G. Physical exercise as adjuvant therapy for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:321–9. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnsen AT, Tholstrup D, Petersen MA, et al. Health related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of haematological patients. Eur J Haematol 2009;83:139–48. 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01250.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Høybye Mterp, Dalton Soksbjerg, Christensen J, et al. Research in Danish cancer rehabilitation: social characteristics and late effects of cancer among participants in the FOCARE research project. Acta Oncol 2008;47:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hansen DG, Larsen PV, Holm LV, et al. Association between unmet needs and quality of life of cancer patients: a population-based study. Acta Oncol 2013;52:391–9. 10.3109/0284186X.2012.742204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Veloso AG, Sperling C, Holm LV, et al. Unmet needs in cancer rehabilitation during the early cancer trajectory – a nationwide patient survey. Acta Oncol 2013;52:372–81. 10.3109/0284186X.2012.745648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holm LV, Hansen DG, Johansen C, et al. Participation in cancer rehabilitation and unmet needs: a population-based cohort study. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2913–24. 10.1007/s00520-012-1420-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jepsen Lene Østergaard, Høybye MT, Hansen DG, et al. Outpatient management of intensively treated acute leukemia patients-the patients' perspective. Support Care Cancer 2016;24 10.1007/s00520-015-3012-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jepsen Lene Østergaard, Friis LS, Hansen DG, et al. Living with outpatient management as spouse to intensively treated acute leukemia patients. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216821 10.1371/journal.pone.0216821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kristiansen M, Adamsen L, Brinkmann FK, et al. Need for strengthened focus on cancer rehabilitation in Danish municipalities. Dan Med J 2015;62:A5045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization Rehabilitation 2015.

- 19. World Health Organization International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) 2001.

- 20. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Midtgaard J, Baadsgaard MT, Møller T, et al. Self-Reported physical activity behaviour; exercise motivation and information among Danish adult cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2009;13:116–21. 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lupton D. Consumerism, reflexivity and the medical encounter. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:373–81. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00353-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parsons T. The social system. Reprinted EDN. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Plass A, Koch U. Participation of oncological outpatients in psychosocial support. Psychooncology 2001;10:511–20. 10.1002/pon.543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mikkelsen TH, Søndergaard J, Jensen AB, et al. Cancer rehabilitation: psychosocial rehabilitation needs after discharge from hospital? Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:216–21. 10.1080/02813430802295610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.