Abstract

Objective

To identify the key diagnostic features and causes of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in Japanese patients.

Design

Multicentre prospective study.

Setting

Sixteen hospitals affiliated with the Japanese Society of Hospital General Medicine, covering the East and West regions of Japan.

Participants

Patient aged ≥20 years diagnosed with classic FUO (axillary temperature≥38.0°C at least twice within a 3-week period, cause unknown after three outpatient visits or 3 days of hospitalisation). A total of 141 cases met the criteria and were recruited from January 2016 to December 2017.

Intervention

Japanese standard diagnostic examinations.

Outcome measures

Data collected include usual biochemical blood tests, inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C reactive (CRP) protein level, procalcitonin level), imaging results, autopsy findings (if performed) and final diagnosis.

Results

The most frequent age group was 65–79 years old (mean: 58.6±9.1 years). The most frequent cause of FUO was non-infectious inflammatory disease. After a 6-month follow-up period, 21.3% of cases remained undiagnosed. The types of diseases causing FUO were significantly correlated with age and prognosis. Between patients with and without a final diagnosis, there was no difference in CRP level between patients with and without a final diagnosis (p=0.121). A significant difference in diagnosis of a causative disease was found between patients who did or did not receive an ESR test (p=0.041). Of the 35 patients with an abnormal ESR value, 28 (80%) had causative disease identified.

Conclusions

Age may be a key factor in the differential diagnosis of FUO; the ESR test may be of value in the FUO evaluation process. These results may provide clinicians with insight into the management of FUO to allow adequate treatment according to the cause of the disease.

Keywords: fever of unknown origin, elderly, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, prospective studies, aging population, Japan

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest multicentre prospective study of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in Japanese hospitals.

The locations of the hospitals involved are geographically dispersed across the country, covering the eastern and western regions of Japan, representing the largest FUO data in Japan.

Key diagnostic features and the causes of FUO were analysed with respect to patients’ medical histories, physical examination findings, standard blood tests and imaging examinations.

Despite this being the largest data sample collected from Japanese hospitals, the sample size is still small; caution should be taken when generalising the results.

Introduction

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) has many possible causes which can vary depending on region and time period.1–3 FUO was first described in the medical literature in 19304 and defined in 1961.5 Since then, a significantly changing spectrum of diseases causing FUO has been reported.6–12 The causes of FUO have now been classified as infections, non-infectious inflammatory diseases (NIID), malignancies, other conditions and unknown.1 3 The proportion of different causative diseases of FUO has changed over time,13 with fewer cases of FUO caused by infections and neoplasms over the past 40–50 years.14 NIID is now the most common cause of FUO in adults,1 15 while infectious diseases are most common in children.16 17 In recent studies from Europe and the USA, the percentage of patients with unknown FUO varied from 7% to 53%.9 Geographic factors may partly contribute to the proportion of FUO cases attributable to different causes.

Recent advances in immunohistopathology and modern imaging make the diagnosis of FUO easier, but definitive diagnosis is often difficult and cannot be achieved in up to 50% of cases.2 3 18 Most previous studies of FUO have focused on its aetiology and prevalence,3 outcomes or the diagnostic value of such tools as inflammatory markers19 20 or positron emission tomography (PET).21–24 However, limited studies have assessed the clinical utility of standard inflammatory markers, even though their use is now widespread.1 The final diagnosis of FUO varies with age;18 25 the most difficult to diagnose cases of FUO have no signs, with the causes remaining unknown.2 Thus, FUO requires a specific diagnostic approach.

The medical evaluation of elderly patients requires a different perspective from that needed for younger patients.18 26 Japan has a high proportion of elderly citizens. People aged 65 and older now constitute fully a quarter of the total population.27 Recently, the first nationwide multicentre retrospective study of FUO in Japan was conducted, reporting the related diagnostic workup and identified diseases to consider when evaluating FUO.1 3 However, the aetiology of FUO, its subjective symptoms and the usefulness of diagnostic tools and techniques in diagnosing FUO in the elderly had not been investigated in detail. The purpose of the multicentre prospective study is thus to update the current understanding of FUO with the addition of more patients in geographically dispersed Japanese hospitals. We aimed to identify the key symptoms and signs, diagnostic features and causes of FUO with respect to patient medical history, physical examination findings, standard blood tests and imaging examinations.

Patients and methods

Patients

This prospective study assessed patients aged ≥20 years with classic FUO from 16 hospitals (encompassing the eastern and western regions of Japan) affiliated with the Japanese Society of Hospital General Medicine, between January 2016 and December 2017. Classic FUO was diagnosed based on the definition used in Naito et al1 in patients meeting all of the following criteria: (1) fever≥38.0°C at least twice within a 3-week period; (2) unknown aetiology of fever after three outpatient visits or 3 days of hospitalisation and (3) no diagnosis of immunodeficiency or confirmed HIV infection prior to fever onset.

The following data from patients were collected during a 6-month follow-up period and recorded on standardised case report forms: patient characteristics (sex, age, comorbidities, medical history and symptoms); physical examination; blood tests (blood count, general biochemical tests, inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C reactive protein (CRP) level, procalcitonin level); results of blood culture if performed; results of imaging studies and endoscopy if performed; results of cytology, histology and genetic testing or autopsy findings if performed and final diagnosis, day of diagnosis and follow-up diagnosis outcome. In addition to analysing the frequency of different causative diseases and outcomes of FUO cases, we evaluated the association between the presence or absence of examination for diagnostic evaluation, the number of days to diagnosis and the clinical follow-up results of inflammatory markers and other imaging tests.

Final diagnoses of the cause of FUO were classified into: infections, NIID, malignancies, other conditions and unknown. Unknown was defined as having no definitive diagnosis after 6 months of clinical investigation.

Statistical analysis

The authors developed cross-tables to present the number of patients and the percentage of those with a final diagnosis of FUO according to symptoms, diagnostic evaluation and time intervals. We performed χ² test to compare the differences between different classes of final diagnosis and all listed factors. We constructed logistic regression models to examine the likelihood of an unknown final diagnosis. All statistic assessments were two-sided and evaluated at the 0.05 level of significance. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Patient and public involvement statement

No patients or public were involved in the design and conduct of this study. Outcome measures were not affected by patient’s experience or preferences.

Results

Patient characteristics

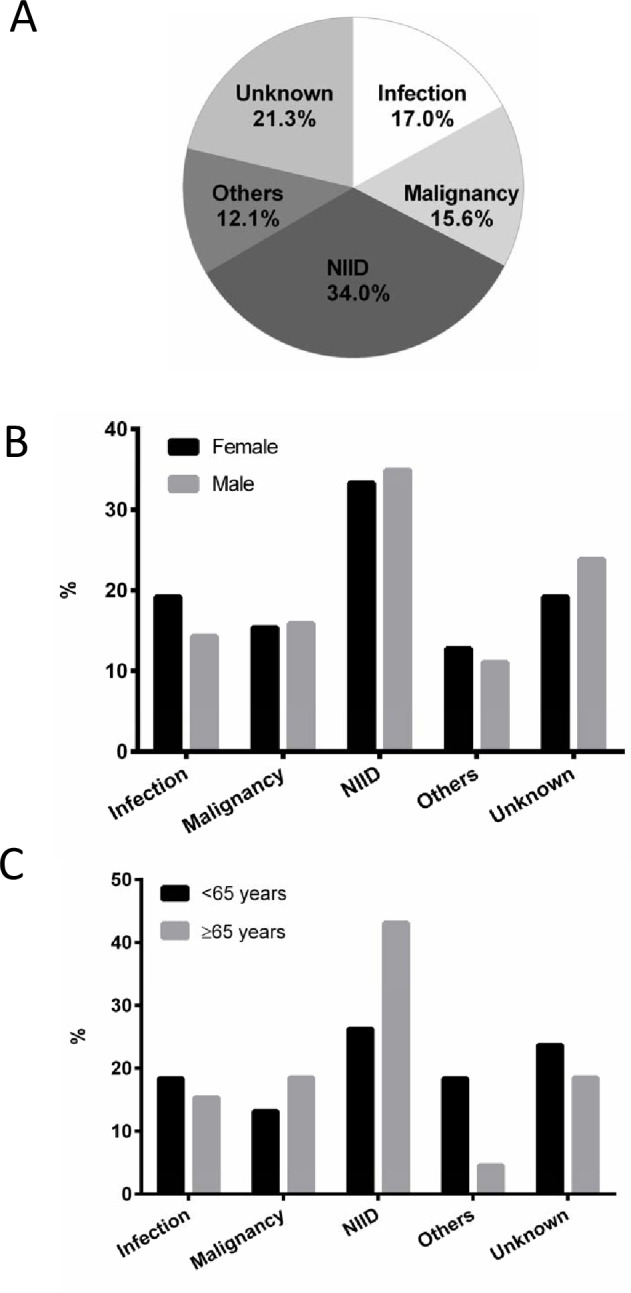

A total of 141 patients who met the criteria of FUO were prospectively recruited from 16 hospitals, including 78 females (55.3%) and 63 males (44.7%), with a median age of 62 years (range: 22–94 years; IQR: 42–74 years). The largest age group was those 65–79 years (n=47). Infections (n=24; 17.0%) and NIID (n=48; 34.0%) constituted the most common known causes of fever in our patient population (figure 1A). Infectious diseases included viral infection (n=5), infective endocarditis (n=4) and tuberculosis (n=2). The most common NIID were adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) (n=7), polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) (n=6), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (n=6) and rheumatoid arthritis (n=4). Twenty-two patients (15.6%) were diagnosed with malignant neoplasm, of whom 11 had malignant lymphoma. Seventeen patients (12.1%) were diagnosed with other causes, such as histiocytic necrotising lymphadenitis (n=3) and subacute thyroiditis (n=2). The cause in 21.3% (n=30) of cases remained unknown (table 1). Of all patients with FUO, more than 50% of those with infections, malignancy, NIID and other causes required <100 days from the time of fever onset to the final diagnosis. NIID required the shortest time to be diagnosed (median 70.0 days, IQR: 54.5–107.5 days) (online supplementary table S1).

Figure 1.

Final diagnosis of FUO. The distribution of final diagnosis of FUO by causative disease (A), sex (B) and age group (<65 years or older) (C). FUO, fever of unknown origin; NIID, non-infectious inflammatory disease.

Table 1.

Description of final diagnosis of fever of unknown origin

| Final diagnosis | N (%) |

| Infectious disease | 24 (17.0%) |

| Viral infection | 5 |

| Infective endocarditis | 4 |

| Tuberculosis | 2 |

| Malignancy | 22 (15.6%) |

| Malignant lymphoma | 11 |

| Non-infectious inflammatory disease | 48 (34.0%) |

| Adult-onset Still disease | 7 |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 6 |

| ANCA-associated vasculitis | 6 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 |

| Others | 17 (12.1%) |

| Histiocytic necrotising lymphadenitis | 3 |

| Subacute thyroiditis | 2 |

| Unknown | 30 (21.3%) |

ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

bmjopen-2019-032059supp001.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)

Figure 1B,C show the distribution of the final diagnosis of FUO by sex and age. The final diagnosis of FUO had no significant correlation with sex (figure 1B; χ2=1.0, df=4, p=0.916) but there was a significant correlation with age (figure 1C; χ2=9.7, df=4, p=0.046). NIIDs constituted the major cause among patients aged ≥65 years (43.1%) and those <65 years (26.3%). A lower percentage of patients aged ≥65 years (4.6%) were diagnosed with other causative diseases compared with those aged <65 years (18.4%).

Symptoms and signs

The comorbidities and symptoms in patients with FUO by final diagnosis are presented in table 2. Comorbidities included chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia. A much higher percentage of patients with comorbidities were diagnosed with malignant neoplasm than those without (19.3% vs 9.6%). The major cause of FUO in patients without comorbidities was NIID (40.4%). Higher percentages of patients with respiratory (33.3%) and gastrointestinal (23.8%) symptoms were diagnosed with infectious diseases. Furthermore, the cause of FUO was NIID in most patients with symptoms of arthralgia (61.4%) or muscle pain (63.2%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with fever of unknown origin by types of final diagnosis

| Variables* | Final diagnosis | ||||||

| Total | Infection† | Malignancy† | NIID† | Other† | Unknown† | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 88 | 16 (18.2%) | 17 (19.3%) | 26 (29.5%) | 10 (11.4%) | 19 (21.6%) |

| No | 52 | 8 (15.4%) | 5 (9.6%) | 21 (40.4%) | 7 (13.5%) | 11 (21.2%) | |

| Subjective symptoms | |||||||

| Headache | Yes | 23 | 3 (13.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 9 (39.1%) | 4 (17.4%) | 6 (26.1%) |

| No | 116 | 20 (17.2%) | 21 (18.1%) | 39 (33.6%) | 12 (10.3%) | 24 (20.7%) | |

| Chest pain | Yes | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| No | 136 | 22 (16.2%) | 22 (16.2%) | 46 (33.8%) | 17 (12.5%) | 29 (21.3%) | |

| Respiratory symptoms | Yes | 24 | 8 (33.3%) | 5 (20.8%) | 2 (8.3%) | 4 (16.7%) | 5 (20.7%) |

| No | 116 | 16 (13.8%) | 17 (14.7%) | 46 (39.7%) | 13 (11.2%) | 24 (21.6%) | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | Yes | 21 | 5 (23.8%) | 4 (19.0%) | 3 (14.3%) | 2 (9.5%) | 7 (33.3%) |

| No | 119 | 19 (16.0%) | 18 (15.1%) | 44 (37.0%) | 15 (12.6%) | 23 (19.3%) | |

| Stomach ache | Yes | 14 | 2 (14.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (14.3%) |

| No | 125 | 21 (16.8%) | 19 (15.2%) | 42 (33.6%) | 15 (12.0%) | 28 (22.4%) | |

| Arthralgia | Yes | 44 | 5 (11.4%) | 2 (4.5%) | 27 (61.4%) | 4 (9.2%) | 6 (13.6%) |

| No | 95 | 18 (18.9%) | 20 (21.1%) | 21 (22.1%) | 12 (12.6%) | 24 (25.3%) | |

| Muscle pain | Yes | 19 | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (63.2%) | 1 (5.3%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| No | 119 | 21 (17.6%) | 21 (17.6%) | 36 (30.3%) | 15 (12.6%) | 26 (21.8%) | |

| Lymph node enlargement | Yes | 15 | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| No | 125 | 21 (16.8%) | 19 (15.2%) | 45 (36.0%) | 12 (9.6%) | 28 (22.4%) | |

| Rash | Yes | 32 | 2 (6.3%) | 6 (18.8%) | 13 (40.6%) | 5 (15.6%) | 6 (18.8%) |

| No | 109 | 22 (20.2%) | 16 (14.7%) | 35 (32.1%) | 12 (11.0%) | 24 (22.0%) | |

| Diagnostic evaluation | |||||||

| WBC‡ | Yes | 141 | 24 (17.0%) | 22 (15.6%) | 48 (34.0%) | 17 (12.1%) | 30 (21.3%) |

| CRP‡ | Yes | 141 | 24 (15.6%) | 22 (15.6%) | 48 (34.0%) | 17 (12.1%) | 30 (21.3%) |

| ESR | Yes | 115 | 14 (12.2%) | 20 (17.4%) | 40 (34.8%) | 12 (10.4%) | 29 (25.2%) |

| No | 26 | 10 (38.5%) | 2 (7.7%) | 8 (30.8%) | 5 (19.2%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

| Procalcitonin | Yes | 54 | 8 (14.8%) | 7 (13.0%) | 20 (37.0%) | 6 (11.1%) | 13 (24.1%) |

| No | 87 | 16 (18.4%) | 15 (17.2%) | 28 (32.2%) | 11 (12.6%) | 17 (19.5%) | |

| Blood culture | Yes | 125 | 23 (18.4%) | 18 (14.4%) | 42 (33.6%) | 13 (10.4%) | 29 (23.2%) |

| No | 16 | 1 (6.3%) | 4 (25.0%) | 6 (37.5%) | 4 (25.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | |

| Autopsy | Yes | 6 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| No | 133 | 22 (16.5%) | 20 (15.0%) | 46 (34.6%) | 17 (12.8%) | 28 (21.1%) | |

| PET | Yes | 44 | 4 (9.1%) | 10 (22.7%) | 16 (36.4%) | 3 (6.8%) | 11 (25.0%) |

| No | 97 | 20 (20.6%) | 12 (12.4%) | 32 (33.0%) | 14 (14.4%) | 19 (19.6%) | |

| Ga scintigraphy | Yes | 40 | 2 (5.0%) | 8 (20.0%) | 16 (40.0%) | 3 (7.5%) | 11 (27.5%) |

| No | 101 | 22 (21.8%) | 14 (13.9%) | 32 (31.7%) | 14 (13.9%) | 19 (18.8%) | |

*Missing data would not be reported.

†Percentage was calculated as number of patients who performed examination divided by total patients for each condition.

‡WBC and CRP were performed on all patients.

CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Ga, gallium; NIID, non-infectious inflammatory disease; PET, positron emission tomography; WBC, white blood cells count.

Biochemical and imaging results

White blood cells (WBC) and CRP were examined in all patients, while 81.6% of patients were tested for ESR and 88.7% for blood culture (online supplementary figure S1). Only 38.3% of patients had procalcitonin tests. One in four or five patients underwent imaging scans (28.4% for gallium scintigraphy and 31.2% for PET). Autopsy was performed in only 4.3% of patients. Patients who underwent an ESR test had a greater likelihood of being diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm (17.4%) or unknown cause (25.2%) compared with those without an ESR test. Patients who had undergone an imaging examination had a relatively greater likelihood of being diagnosed with malignancy or NIID compared with those without imaging examinations (table 2).

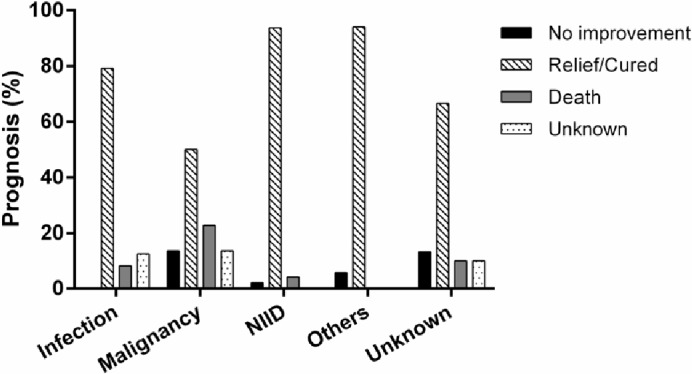

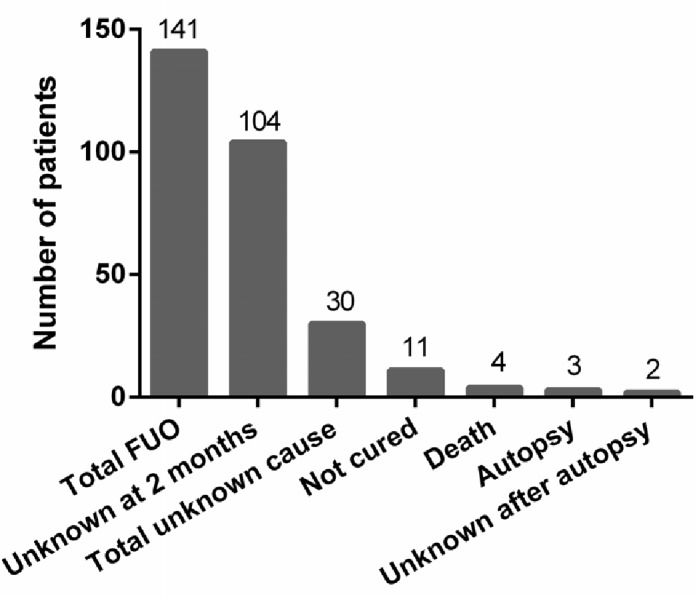

There was a significant association between the aetiology of FUO and the prognosis of patients (figure 2; χ2=27.6, df=12, p=0.006). Most patients with FUO with different causative diseases generally were cured or experienced relief. However, patients with malignancy or unknown causes had higher mortality rates (22.7% and 12.9%, respectively) (figure 2). Among all 141 patients, the cause of fever was not identified in 104 patients at 2 months (figure 3). At the end of the follow-up period, the cause of FUO remained unknown in 30 patients and 11 patients were not cured or had no symptom relief. Four deaths occurred among these patients. Pathological autopsy was performed on a small proportion of those who died (n=3); two cases remained unknown after autopsy (figure 3).

Figure 2.

The distribution of final diagnosis of FUO by prognostic outcomes. There was an association between type of causative disease and prognosis (χ2=27.6, df=12, p=0.006). FUO, fever of unknown origin; NIID, non-infectious inflammatory disease.

Figure 3.

Time course and prognostic outcomes for patients with FUO. FUO, fever of unknown origin.

Tests were performed for diagnostic evaluation and abnormal readings were defined as in Naito et al:1 WBC: 4000–8000; CRP: 0.3; ESR >100 mm/hour and procalcitonin ≥0.25 ng/mL. Most patients with unknown cause of FUO had abnormal WBC and CRP levels (WBC: 56.7%; CRP: 73.3%, respectively), while a smaller percentage of patients had abnormal ESR and procalcitonin levels (ESR: 24.1%; procalcitonin: 23.1%). Table 3 shows the association of patient demographics, clinical characteristics and diagnostic examinations for patients with known and unknown causes of FUO. There was a significant association between having undergone ESR examination and unknown final diagnosis of FUO (OR=8.43, 95% CI 1.09 to 65.00, p=0.041). Furthermore, 80% (28 of 35) of patients with an abnormal ESR value had a final diagnosis. No other variables differed significantly between the groups with known and unknown cause of FUO (all p>0.05) (table 3).

Table 3.

The association of patient demographics, clinical characteristics and diagnostic evaluation between patients with known and unknown causes of FUO

| Variables | Known cause* | Unknown cause* | OR (95% CI) | P value† | |

| Age group | ≥65 years | 53 (81.5%) | 12 (18.5%) | 0.73 (0.32 to 1.66) | 0.451 |

| <65 years | 58 (76.3%) | 18 (23.7%) | 1.00 | ||

| Sex | Male | 48 (76.2%) | 15 (23.8%) | 1.31 (0.59 to 2.95) | 0.510 |

| Female | 63 (80.8%) | 15 (19.2%) | 1.00 | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 69 (78.4%) | 19 (21.6%) | 1.03 (0.44 to 2.37) | 0.951 |

| No | 41 (78.8%) | 11 (21.2%) | 1.00 | ||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Headache | Yes | 17 (73.9%) | 6 (26.1%) | 1.35 (0.48 to 3.80) | 0.566 |

| No | 92 (79.3%) | 24 (20.7%) | 1.00 | ||

| Chest pain | Yes | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1.85 (0.16 to 20.07) | 0.622 |

| No | 107 (78.7%) | 29 (21.3%) | 1.00 | ||

| Respiratory symptoms | Yes | 19 (79.2%) | 5 (20.8%) | 1.01 (0.34 to 2.98) | 0.987 |

| No | 92 (79.3%) | 24 (20.7%) | 1.00 | ||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | Yes | 14 (66.7%) | 7 (33.3%) | 2.09 (0.76 to 5.76) | 0.155 |

| No | 96 (80.7%) | 23 (19.3%) | 1.00 | ||

| Stomach ache | Yes | 12 (85.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.58 (0.12 to 2.73) | 0.489 |

| No | 97 (77.6%) | 28 (22.4%) | 1.00 | ||

| Arthralgia | Yes | 38 (86.4%) | 6 (13.6%) | 0.47 (0.18 to 1.24) | 0.127 |

| No | 71 (74.7%) | 24 (25.3%) | 1.00 | ||

| Muscle pain | Yes | 15 (78.9%) | 4 (21.1%) | 0.95 (0.29 to 3.12) | 0.938 |

| No | 93 (78.2%) | 26 (21.8%) | 1.00 | ||

| Lymph node enlargement | Yes | 13 (86.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.53 (0.11 to 2.50) | 0.425 |

| No | 97 (77.6%) | 28 (22.4%) | 1.00 | ||

| Rash | Yes | 26 (81.3%) | 6 (18.8%) | 0.82 (0.30 to 2.21) | 0.692 |

| No | 85 (78.0%) | 24 (22.0%) | 1.00 | ||

| Ancillary findings | |||||

| WBC | Yes | 111 (78.7%) | 30 (21.3%) | NA | NA |

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| CRP | Yes | 111 (78.7%) | 30 (21.3%) | NA | NA |

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| ESR | Yes | 86 (74.8%) | 29 (25.2%) | 8.43 (1.09 to 65.00) | 0.041 |

| No | 25 (96.2%) | 1 (3.8%) | 1.00 | ||

| Procalcitonin | Yes | 41 (75.9%) | 13 (24.1%) | 1.31 (0.58 to 2.96) | 0.523 |

| No | 70 (80.5%) | 17 (19.5%) | 1.00 | ||

| Blood culture | Yes | 96 (76.8%) | 29 (23.2%) | 4.53 (0.57 to 35.78) | 0.152 |

| No | 15 (93.8%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1.00 | ||

| Autopsy | Yes | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1.88 (0.33 to 10.77) | 0.481 |

| No | 105 (78.9%) | 28 (21.1%) | 1.00 | ||

| PET | Yes | 33 (75.0%) | 11 (25.0%) | 1.37 (0.59 to 3.19) | 0.468 |

| No | 78 (80.4%) | 19 (19.6%) | 1.00 | ||

| Ga scintigraphy | Yes | 29 (72.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | 1.64 (0.70 to 3.85) | 0.258 |

| No | 82 (81.2%) | 19 (18.8%) | 1.00 |

Stomach ache is different from gastrointestinal symptoms, which include vomiting and diarrhoea.

*Percentage was calculated as the number of patients who received an examination divided by the total patients for each condition.

†χ² tests were performed.

CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Ga, gallium; PET, positron emission tomography; WBC, white blood cell count.

Discussion

This prospective multicentre study represents the largest report of FUO data in Japanese patients to date. Of these 141 patients with FUO recruited from 16 hospitals, the most frequent age group was 65–79 years old, with the most frequent cause being NIID. There was a significant correlation between the final diagnosis of FUO and the age of patients (≥65 and<65 years), but not with sex. While most studies have identified NIID as the most common cause of FUO in Japan,1 15 28 29 our 2013 study found similar rates of NIID as a cause of FUO in participants ≥65 and <65 years.3 The different selection strategies of the age groups and the ageing of the Japanese population may contribute to the differences in these findings between studies. In Japan, adults age ≥65 accounted for 26.7% of the 127.11 million population in 2016,27 30 and will increase to 40% in 2050, according to a new analysis.31 In this study, 46.1% of patients were ≥65 years, an increase since 2013 (42.1%).3 Moreover, this trend should also be considered in Western countries, where ageing of the population is also expected.31 A diagnosis of NIID, which occurs significantly more often in elderly patients,1 consequently must be considered first for an FUO, particularly in patients ≥65 years. Of interest, AOSD was the most frequent NIID cause of FUO in this population. Several factors may explain this seemingly high proportion (5%). One possible justification could be that these patients may have AOSD susceptibility genes. Susceptibility of AOSD in the Japanese population depends on the genotype combinations of the HLD DRB1 and DQB1 alleles, and predisposing risk has been found associated with the haplotype DRB1*15:01-DQB1*06:02 in Japanese patients with AOSD.32 However, genotyping results were not available for this study.

Difference in causative disease between populations could be influenced by factors such as geographic location, zoonotic characteristics and the economic and medical organisation of the local healthcare system. Infectious disease was the leading cause of FUO in South-East Europe, as reported by Baymakova et al in 2016.33 Infection was the second most common causes of fever in our patient population. Our previous study in 2013 demonstrated that PMR and HIV should be considered as causes of FUO.3 However, HIV was not found in this study, possibly due to the efficiency of HIV testing in Japan. The frequency of unknown cause in our study was comparable to that found previously in 2013.3

The availability of new diagnostic techniques, including CT, PET imaging, improved culture techniques and advanced serological assays, has changed both the spectrum of diseases causing FUO and the time to reveal the final diagnosis. In a previous study, the cause of FUO diagnosed after ≥100 days was malignancy.3 In this study, more than 50% of patients with FUO with infections, malignancy, NIID and other causes had a final diagnosis within 100 days of fever onset. Similarly, in a series of patients with FUO studied in Europe and USA, 30%–50% were of unknown cause after a follow-up of ≥100 days.6 9 34

In the present study, we evaluated key symptoms and signs in patients with FUO to determine which were diagnostically useful. We found that comorbidities were the main symptoms and signs in FUO caused by malignant neoplasms. Patients with infectious diseases often had respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, while those with NIID often had arthralgia or muscle pain. Although the various symptoms/signs were not directly related to the final diagnosis of FUO,14 their presence might help improve the differential diagnosis in patients with FUO.

A systemic review from 2003 reported that the prevalence of FUO was 1.5%–3% in all hospitalised patients, and mortality in these patients was 12%–35%.35 We found that the aetiology of FUO was significantly associated with prognosis; patients with FUO diagnosed with malignancy or unknown causes had higher mortality rates. A Danish study also found that patients with FUO with malignancy had poor prognosis.36 Little is known about the prognosis of patients with FUO of unknown cause. In our study, 4 of 30 (13.3%) patients with FUO of unknown cause died during within 6 months; the cause of FUO remained unknown after autopsy in two of these patients. In patients with FUO of unknown cause, Dutch studies showed mortality rates of 2.0%–4.0%6 36 and other western-European studies reported mortality rates of 2.0%–19.0%.7 10 37–39 The variances among studies may be due to differences in patient selection, study design or healthcare systems.

Since there is no standard diagnostic approach in FUO, classic test features are difficult to apply in FUO studies. Of all positive biochemical tests, only 1.7% contributed indirectly to diagnosis in a Turkey FUO study.13 Despite advances in diagnostic tests and techniques, a significant proportion of all cases remains undiagnosed.40 Our previous study found that 14.9% of patients with FUO had an ESR >100 mm/hour, including 5 with FUO of unknown cause.1 In the current study, 35 of 115 patients (30.4%) had an abnormal ESR test result; in these, the cause of FUO was identified in 80% of patients. In addition, there was a significant association between known cause and ancillary ESR test, but not with other variables such as procalcitonin or PET. Therefore, the current study demonstrated the usefulness of ESR in evaluating FUO. However, further investigation is required. We speculate that future FUO research may be leaving the twilight zone as diagnostic microcellular research technologies emerge from the laboratory to point-of-care rapid diagnostic kits. We await further advances in diagnostic artificial intelligence to expose FUO cause in more cases.41 42

The present study has the following limitations. First, despite this being the largest data sample ever collected from geographically dispersed Japanese hospitals, the sample size is still small; caution should be taken when generalising our results. Also, we did not establish uniformity of the diagnostic criterion used in this study, which may have resulted in overdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of specific disease categories. Uncertainty of diagnosis was not addressed. Finally, our follow-up database was not designed to include records of spontaneous fever remission.43

In conclusion, evaluating and determining the cause of a fever is complex. The availability of new diagnostic techniques (including CT and PET imaging), improved culture techniques and recent advances in serological assays have all changed both the spectrum of diseases causing FUO and the time needed to reach a final diagnosis. Our study identified age and ESR as potentially important factors useful in assisting clinicians navigate the paths to diagnosing FUO. These advances, together with future development of multimicrobial and cancer cell detection tools, may allow faster determination of the causes of FUO and further improve the prognosis of patients with FUO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Convergence CT Japan K.K for conducting statistical analysis, data interpretation and reviewing this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge support from Tatsuo Ishizuka, Kenji Kanazawa, Nobuki Nanki, Megumi Higaki and Koichi Mashiba for valuable administrative and research assistance throughout this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: TN and ST. Acquisition of data: TI, TS, HM, SY, JT, KA, KY, HO, SS, MK, SO, HA, HK and MT. Analysis and interpretation of data: TN, NI, KA and MT. Drafting of the manuscript: TN and MT. Critical revision of the manuscript: NI, ST and JH. Final approval of the manuscript: TN, TS, SY, HA, HK and JH.

Funding: This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, Japan Project Number: 16K09257.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Research Ethics Committee of Juntendo University School of Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Naito T, Torikai K, Mizooka M, et al. Relationships between causes of fever of unknown origin and inflammatory markers: a multicenter collaborative retrospective study. Intern Med 2015;54:1989–94. 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cunha BA, Lortholary O, Cunha CB. Fever of unknown origin: a clinical approach. Am J Med 2015;128:1138 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naito T, Mizooka M, Mitsumoto F, et al. Diagnostic workup for fever of unknown origin: a multicenter collaborative retrospective study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003971 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alt HL, Barker MH. Fever of unknown origin. JAMA 1930;94:1457–61. 10.1001/jama.1930.02710450001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petersdorf RG, Beeson PB. Fever of unexplained origin: report on 100 cases. Medicine 1961;40:1–30. 10.1097/00005792-196102000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Kleijn EMHA, Vandenbroucke JP, van der Meer JWM. Fever of unknown origin (FUO): I. A prospective multicenter study of 167 patients with FUO, using fixed epidemiologic entry criteria. Medicine 1997;76:392–400. 10.1097/00005792-199711000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zenone T. Fever of unknown origin in adults: evaluation of 144 cases in a non-university Hospital. Scand J Infect Dis 2006;38:632–8. 10.1080/00365540600606564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller RF, Hingorami AD, Foley NM. Pyrexia of undetermined origin in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS. Int J STD AIDS 1996;7:170–5. 10.1258/0956462961917564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bleeker-Rovers CP, Vos FJ, de Kleijn EMHA, et al. A prospective multicenter study on fever of unknown origin: the yield of a structured diagnostic protocol. Medicine 2007;86:26–38. 10.1097/MD.0b013e31802fe858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knockaert DC, Vanderschueren S, Blockmans D. Fever of unknown origin in adults: 40 years on. J Intern Med 2003;253:263–75. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01120.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Durack DT, Street AC. Fever of unknown origin--reexamined and redefined. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis 1991;11:35–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baymakova M, Popov GT, Andonova R, et al. Fever of unknown origin and Q-fever: a case series in a Bulgarian Hospital. Caspian J Intern Med 2019;10:102–6. 10.22088/cjim.10.1.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kucukardali Y, Oncul O, Cavuslu S, et al. The spectrum of diseases causing fever of unknown origin in Turkey: a multicenter study. Int J Infect Dis 2008;12:71–9. 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balink H, Verberne HJ, Bennink RJ, et al. A rationale for the use of F18-FDG PET/CT in fever and inflammation of unknown origin. Int J Mol Imaging 2012;2012:1–12. 10.1155/2012/165080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takeda R, Mizooka M, Kobayashi T, et al. Key diagnostic features of fever of unknown origin: medical history and physical findings. J Gen Fam Med 2017;18:131–4. 10.1002/jgf2.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim Y-S, Kim K-R, Kang J-M, et al. Etiology and clinical characteristics of fever of unknown origin in children: a 15-year experience in a single center. Korean J Pediatr 2017;60:77–85. 10.3345/kjp.2017.60.3.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cho C-Y, Lai C-C, Lee M-L, et al. Clinical analysis of fever of unknown origin in children: a 10-year experience in a Northern Taiwan medical center. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2017;50:40–5. 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tal S, Guller V, Gurevich A. Fever of unknown origin in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 2007;23:649–68. 10.1016/j.cger.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK, et al. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:206–17. 10.1086/421997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kubota K, Nakamoto Y, Tamaki N, et al. FDG-PET for the diagnosis of fever of unknown origin: a Japanese multi-center study. Ann Nucl Med 2011;25:355–64. 10.1007/s12149-011-0470-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kouijzer IJE, Bleeker-Rovers CP, Oyen WJG. FDG-PET in fever of unknown origin. Semin Nucl Med 2013;43:333–9. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kouijzer IJE, Mulders-Manders CM, Bleeker-Rovers CP, et al. Fever of unknown origin: the value of FDG-PET/CT. Semin Nucl Med 2018;48:100–7. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takeuchi M, Dahabreh IJ, Nihashi T, et al. Nuclear imaging for classic fever of unknown origin: meta-analysis. J Nucl Med 2016;57:1913–9. 10.2967/jnumed.116.174391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bleeker-Rovers CP. Positron emission tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose in fever of unknown origin and infectious and non-infectious inflammatory diseases. Netherlands: Radboud University Nijmegen, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Unger M, Karanikas G, Kerschbaumer A, et al. Fever of unknown origin (FUO) revised. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2016;128:796–801. 10.1007/s00508-016-1083-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knockaert DC, Vanneste LJ, Bobbaers HJ. Fever of unknown origin in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:1187–92. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sudo K, Kobayashi J, Noda S, et al. Japan's healthcare policy for the elderly through the concepts of self-help (Ji-jo), mutual aid (Go-jo), social solidarity care (Kyo-jo), and governmental care (Ko-jo). Biosci Trends 2018;12:7–11. 10.5582/bst.2017.01271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iikuni Y, Okada J, Kondo H, et al. Current fever of unknown origin 1982-1992. Intern Med 1994;33:67–73. 10.2169/internalmedicine.33.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shoji S, Imamura A, Imai Y, et al. Fever of unknown origin: a review of 80 patients from the Shin'etsu area of Japan from 1986-1992. Intern Med 1994;33:74–6. 10.2169/internalmedicine.33.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren J, Ma R, Zhang Z-B, et al. Effects of microRNA-330 on vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques formation and vascular endothelial cell proliferation through the Wnt signaling pathway in acute coronary syndrome. J Cell Biochem 2018;119:4514–27. 10.1002/jcb.26584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He W, Goodkind D, Kowal P. U.S. census bureau, International population reports, P95/16-1, an aging world: 2015. Washington, DC: Government Publishing Office, 2016: 1–165. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fujita Y, Furukawa H, Asano T, et al. HLA-DQB1 DPB1 alleles in Japanese patients with adult-onset still's disease. Mod Rheumatol 2019;29:843–7. 10.1080/14397595.2018.1514999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baymakova M, Dikov I, Popov GT. Fever of unknown origin in a Bulgarian hospital: evaluation of 54 cases for a four year-period. J Clin Anal Med 2016;7:70–5. 10.4328/JCAM.3897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hersch EC, Oh RC. Prolonged febrile illness and fever of unknown origin in adults. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mourad O, Palda V, Detsky AS. A comprehensive evidence-based approach to fever of unknown origin. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:545–51. 10.1001/archinte.163.5.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mulders-Manders CM, Engwerda C, Simon A, et al. Long-term prognosis, treatment, and outcome of patients with fever of unknown origin in whom no diagnosis was made despite extensive investigation. Medicine 2018;97:e11241 10.1097/MD.0000000000011241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pedersen TI, Roed C, Knudsen LS, et al. Fever of unknown origin: a retrospective study of 52 cases with evaluation of the diagnostic utility of FDG-PET/CT. Scand J Infect Dis 2012;44:18–23. 10.3109/00365548.2011.603741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Robine A, Hot A, Maucort-Boulch D, et al. Fever of unknown origin in the 2000s: evaluation of 103 cases over eleven years. Presse Med 2014;43:e233–40. 10.1016/j.lpm.2014.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vanderschueren S, Del Biondo E, Ruttens D, et al. Inflammation of unknown origin versus fever of unknown origin: two of a kind. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:415–8. 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Horowitz HW. Fever of unknown origin or fever of too many origins? N Engl J Med 2013;368:197–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1212725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dave VP, Ngo TA, Pernestig A-K, et al. MicroRNA amplification and detection technologies: opportunities and challenges for point of care diagnostics. Lab Invest 2019;99:452–69. 10.1038/s41374-018-0143-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liang H, Tsui BY, Ni H, et al. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat Med 2019;25:433–8. 10.1038/s41591-018-0335-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takeuchi M, Nihashi T, Gafter-Gvili A, et al. Association of 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT results with spontaneous remission in classic fever of unknown origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018;97:e12909 10.1097/MD.0000000000012909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032059supp001.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)