Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the characteristics of patients diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy in Spain, and to revise data on disease management and use of resources in both public and private healthcare centres.

Design

A retrospective multicentre database analysis.

Setting

870 admission records registered between 1997 and 2015 with a diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy were extracted from a Spanish claims database that includes hospital inpatient and outpatient admissions from 313 public and 192 private hospitals in Spain.

Results

Admission files corresponded to 705 patients; 61.99% were males and 38.01% females. Average patient age was 37 years. Disease comorbidities registered during the admission consistently included hypertension, scoliosis and respiratory failures, all associated with the standard disease course. Regarding disease management at the hospital level, patients were mostly admitted through scheduled appointments (58.16%), followed by emergency admissions (41.72%), and into neurology services in 17% of the cases. Mean hospitalisation time was 10.45 days and in-hospital mortality reached 5.29%. The overall direct medical costs of spinal muscular atrophy were €291 525, excluding medication. The average annual cost per admission was €6274, with large variations likely to reflect disease complexity and that increases with length of stay.

Conclusions

The rarity of the disease difficulties the study of demographics and management; yet, an analysis of patient characteristics provides necessary information that can be used by governments to establish more efficient healthcare protocols. This study reflects the impact that individual needs and disease severity can have in disease burden calculations. Forthcoming decision-making policies should take into account medical costs and its variability, as well as pharmaceutical expenses and indirect costs. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the use of healthcare resources of patients with spinal muscular atrophy in Spain.

Keywords: spinal muscular atrophy, direct medical costs, retrospective multicentre study, claims database analysis, Spain

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The application of a retrospective study covering 18 years allows obtaining a clear view of disease status in the country.

The inclusion of inpatient and outpatient care data provides a consistent basis for the analysis of medical costs in specialised care settings.

A higher specificity of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) codes would permit an improved analysis.

The calculation of direct medical costs excludes pharmaceutical expenses, unknown due to their exclusion from patient records.

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare, hereditary and recessive neuromuscular disorder caused by the degeneration of the alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord.1 The term SMA makes reference to a group of genetic disorders characterised by mild to severe muscle atrophy and weakness.

SMA has generally been divided into four to five types based on patients’ motor function and disease age of onset. Type I, also called Werdnig-Hoffmann syndrome, is diagnosed at birth or in the first 6 months of life, and causes severe development limitations that generally lead to patients’ death before 2 years of age. Type II has its onset between 7 and 18 months of age, before the child is able to walk. Type III (Kugelberg-Welander syndrome) can be divided in two subtypes; type IIIa is diagnosed in children of 2–3 years of age, who will have orthopaedic issues; and type IIIb has its onset between 3 years of age and late adolescence, and patients generally have a normal motor development.2 3

A fourth type of SMA has been later described to refer to SMA with an adult onset, in people that are able to walk. Type 0 has been used to refer to the disease in children in the first weeks of their life.2 4

Recent research has allowed identifying and describing most genetic variants associated with SMA, all mutations in the survival of motor neurons (SMN1) gene, but disease pathogenesis is still not fully understood. Data on disease occurrence and epidemiology are also scarce for some regions of the planet. Also, the relative rarity of the disease can lead to major miscalculations in disease prevalence and incidence rates.5

SMA has been estimated to affect 1 in 6000–10 000 children.6 In addition, 1 in 40 individuals are estimated to be carriers of the recessive mutation.

Several studies in countries like Iceland, Sweden, the UK, Germany, Italy and Canada show an irregular distribution of SMA patients around the world depending on the region and population characteristics.7 SMA incidence in these countries ranged from 6 per 100 000 people in Canada to 13.7 per 100 000 people in Iceland.

In terms of costs, the economic impact of attending SMA patients and their care has only been partially evaluated. A previous study in Spain based on questionnaires filled by caregivers showed the high costs that these assume in terms of healthcare and indirect costs associated with the disease, and a posterior similar study in Australia confirmed that the burden for families is extremely high8 9; nevertheless, the costs it has for healthcare systems have not been evaluated in the country.

Thus, the objective of this study was to analyse SMA patient characteristics and number of diagnoses between 1997 and 2015 in Spain, and to revise data on disease management and these patients’ use of resources in both public and private healthcare centres.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted based on data from the Spanish claims database Minimum Basic Data Set (Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos (CMBD)),10 a database administered by the Spanish Ministry of Health that compiles records from 313 public and 192 private hospitals representative of the Spanish population.

All admission files registered between 1997 and 2015 in which SMA was listed as the principal diagnosis (admission motive) were identified and extracted via the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) codes 335.0, 335.10, 335.11, 335.19 and 335.21 corresponding to patients with Werdnig-Hoffmann, Kugelberg-Welander, any progressive SMA, unspecified SMA and other SMA types.

Each admission file contained patient general information (sex, age and region of residence), admission details (type of admission, length of stay and destination after discharge), secondary diagnoses and procedures performed during the admission (codified using ICD9-CM and ICD9, Procedure Classification System (ICD9-PCS) codes) and the hospitalisation cost that included treatment (examination, medication and surgery) and costs associated to medical staff, equipment and resources. Such cost was given as a total value based on the tariffs of medical procedures determined by the Spanish Ministry of Health for the year when the admission took place. The years 1997 and 1998 were excluded from the analysis of secondary care costs to ensure data consistency after the detection of codification errors.

The complete admission data were used to analyse disease management. For the analysis of patient demographics and comorbidities, only the first admission per patient during the study period (1997–2015) was considered.

Records were extracted after the re-coding of health centres and medical history identifiers to maintain anonymity in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data presentation is mainly descriptive. All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel Professional Plus 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the research or the study design. Results will not be disseminated to patients included in the database.

Results

Patient characteristics

Altogether, 870 inpatient and outpatient admissions were identified in the CMBD database, which corresponded to single and repeated admissions of 705 patients with SMA.

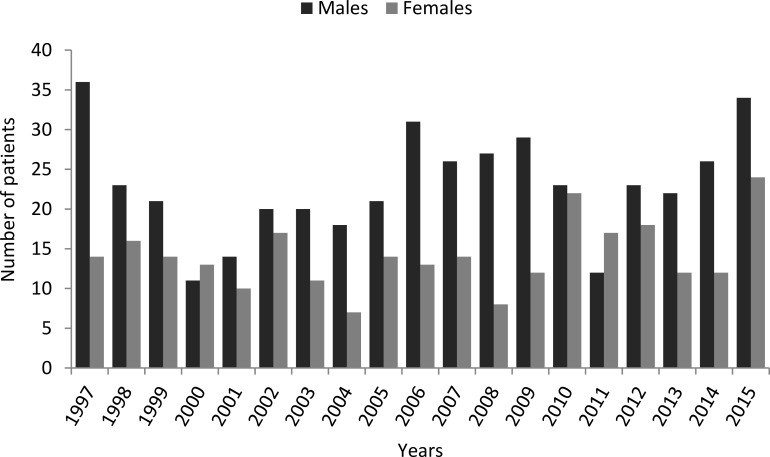

The 61.99% of the 705 patients included in the study were males, while 38.01% were females, with relatively large variations in these proportions over the years (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of male and female patients per year.

When considering solely data recovered from the first admission per patient during the study period, mean patient age was 37 years, with virtually no differences among sexes. To minimise errors, any changes in patients’ mean age at first admission over the study period were measured. Nonetheless, patients’ average age did not exhibit large variations over the years, with a SD of only 5.87 years (data not shown).

Each file included data of secondary diagnoses registered during the admission, used to analyse comorbidities. The most repeated comorbidities in patients with SMA were: hypertension (14.89%), scoliosis (10.21%), chronic respiratory failure (6.38%), diabetes mellitus (5.96%), tobacco use disorders (5.96%) and acute respiratory failure (5.25%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Comorbidities in SMA patients

| Disease description (ICD9-CM code) | Number of patients | % of patients |

| Unspecified essential hypertension (401.9) | 105 | 14.89 |

| Scoliosis associated with other conditions (737.43) | 72 | 10.21 |

| Chronic respiratory failure (518.83) | 45 | 6.38 |

| Diabetes mellitus type I-II (250) | 42 | 5.96 |

| Tobacco use disorders (305.1) | 42 | 5.96 |

| Acute respiratory failure (518.81) | 37 | 5.25 |

ICD9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

Use of healthcare resources

Regarding hospitalisation events, scheduled admissions were predominant (58.16%), followed by emergency admissions (41.72%) (table 2).

Table 2.

Type of admissions, readmissions and discharge of SMA patients

| Origin of admission | Number of admissions | % of admissions |

| Scheduled | 506 | 58.16 |

| Emergency | 363 | 41.72 |

| Others | 1 | 0.12 |

| Destination after discharge | ||

| Home | 796 | 91.50 |

| Death | 46 | 5.29 |

| Other hospitals | 17 | 1.95 |

| Voluntary | 3 | 0.34 |

| Transfer to a social health centre | 2 | 0.23 |

| Others | 6 | 0.69 |

| Readmissions | 99 | 11.38 |

SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

The average hospitalisation time was 10.45 days. Patients were discharged mostly to their residence (91.50%), although 5.29% died during the hospitalisation event. In addition, 11.38% of the patients were readmitted within the following 30 days after discharge.

Neurology admitted 17.70% of the patients, paediatrics 9.08%, traumatology 6.21%, pneumology 5.40%, internal medicine 3.79% and the rest of admissions were into other services or unregistered (table 3). The most repeated procedures performed during the admission were also analysed. Common procedures were related to neuromuscular tests, medical imaging and ventilation or oxygenation (table 3).

Table 3.

Services that attended SMA patients and procedures performed on admission

| Number of patients | % of patients | |

| Service | ||

| Neurology | 154 | 17.70 |

| Paediatrics | 79 | 9.08 |

| Traumatology and orthopaedics | 54 | 6.21 |

| Pneumology | 47 | 5.40 |

| Internal medicine | 33 | 3.79 |

| Procedure ( ICD9-PCS code ) | ||

| Electromyography (93.08) | 182 | 20.92 |

| MRI scan of the brain and brainstem (88.91) | 104 | 11.95 |

| MRI scan of the spinal canal (88.93) | 103 | 11.84 |

| Lumbar puncture (03.31) | 99 | 11.38 |

| Routine chest radiography (87.44) | 74 | 8.51 |

| Microscopic examination of the blood (90.59) | 74 | 8.51 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation (93.90) | 71 | 8.16 |

| Electrocardiogram (89.52) | 67 | 7.70 |

| Arterial blood gas test (89.65) | 57 | 6.55 |

| Other oxygenation procedures (93.96) | 52 | 5.98 |

ICD9-PCS, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Procedure Classification System; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

As for medical costs related to the use of resources, the average annual cost of the disease at the hospital level was €291 525, excluding pharmaceutical expenses. The cost per hospitalisation was on average €6274, ranging from €2569 to €112 067 (table 4). The cost per admission appeared increased in the year 2012 due to the high costs registered in one admission of a patient with Kugelberg-Welander (reaching €112 067); this could reflect the impact in terms of cost that is derived from the most severe cases. The analysis of admission costs per SMA type showed major expenses related to Kugelberg-Welander, averaging €9415, and mean costs per admission of €5770, €5751, €5286 and €5379 in patients with Werdnig-Hoffmann, progressive SMA, other SMA types and unspecified SMA, respectively.

Table 4.

Mean and range of costs per hospital admission per year (1999–2015)

| Year | Mean (SD) | Range | Admissions |

| 1999 | €4196 (€1437) | €2709–€9566 | 39 |

| 2000 | €4051 (€809) | €2709–€7072 | 33 |

| 2001 | €5724 (€7292) | €3023–€40 619 | 25 |

| 2002 | €5437 (€6116) | €3003–€41 395 | 39 |

| 2003 | €4672 (€1275) | €3305–€9282 | 36 |

| 2004 | €7153 (€11 308) | €3400–€47 560 | 29 |

| 2005 | €4584 (€2132) | €2569–€12 589 | 37 |

| 2006 | €4876 (€3402) | €2876–€15 622 | 50 |

| 2007 | €7243 (€7908) | €2997–€55 979 | 55 |

| 2008 | €8048 (€7542) | €3303–€47 907 | 47 |

| 2009 | €5223 (€3323) | €3329–€15 182 | 46 |

| 2010 | €5493 (€3530) | €3541–€21 308 | 57 |

| 2011 | €8981 (€14 145) | €3626–€81 742 | 39 |

| 2012 | €10 088 (€18 472) | €3502–€112 067 | 53 |

| 2013 | €6890 (€9266) | €4129–€69 361 | 51 |

| 2014 | €6644 (€4764) | €3454–€24 947 | 53 |

| 2015 | €7358 (€8098) | €3759–€52 764 | 81 |

Finally, the impact of the length of stay in hospitalisation costs was evaluated. Outpatient admissions displayed a mean cost of €5603 per visit, while inpatient care admissions displayed increasing costs that augmented alongside the length of stay (table 5). Yet, wide variability appeared linked to individual patient needs.

Table 5.

Mean cost per admission per length of stay

| Days | Mean | Range |

| Outpatient care | €5603 | €3400–€8014 |

| Inpatient care | ||

| 1–10 | €5276 | €2569–€81 742 |

| 11–30 | €7858 | €2876–€52 764 |

| 31–60 | €12 369 | €2997–€69 361 |

| >60 | €32 692 | €4061–€112 067 |

The vast majority of patients were financed by the Spanish social security system (94.61%), 1.84% were financed by local corporations, 1.28% by mutual healthcare and the rest were private or unknown.

Discussion

Patient characteristics

The understanding of SMA molecular basis has increased dramatically in the past years; however, patient characteristics, disease occurrence and managing have not been analysed in many countries. Regional disease demographics provide interesting information that can be used by regional governments to establish more efficient healthcare protocols and to develop research that satisfies the population needs. In addition, an irregular geographical distribution of SMA has been previously observed depending on the region and population characteristics,7 thus the interest of understanding any variations that may occur in Spain.

This study sheds light into the current status of SMA in the country via the analysis of medical records from 1997 to 2015. The inclusion of 18 years of records allows a more consistent analysis of a condition with, otherwise, few diagnosed cases. Overall, 705 patients were identified with a diagnosis of SMA in the database, with a proportion 60 to 40 male/female, which is seemingly not explained by the described genetic basis of SMA. Previous studies including data from the USA found proportions of female patients of 54.8% and 56.9% for total SMA and SMA-I, respectively.11 12 However, ICD-9 codes used to identify SMA include variations of the disease as progressive muscular atrophy (Aran-Duchenne disease), known to be more common in males than in females with a ratio of 3:1.13 Patients’ age, on the other hand, is equal in both sexes and relatively high (37 years), although this age registered at first admission cannot be translated to age of diagnosis given the inclusion in the study of patients diagnosed before 1997. In general terms, age of first diagnosis has been estimated around 7.5±6.4 years12; yet, it is highly variable among the distinct SMA types.4 In addition, when diagnosis is based on pre-natal screening, it is considered pre-symptomatic and registered earlier in life.14

Nevertheless, the importance of the typical clinical manifestations of SMA is clear, and its disease comorbidities have been vastly described, including conditions as scoliosis and respiratory failures, commonly diagnosed in this study among SMA patients.15 In fact, previous data suggest that scoliosis is present in virtually all type II and type IIIa SMA patients, and it appears progressively in patients with type IIIb SMA.3 16 Scoliosis can have severe effects in patients’ respiratory capacities, with consequences that justify the prevalence of respiratory failure among these patients.3 This validates the importance to tackle orthopaedic manifestations of SMA in early phases of the disease. On the other hand, the high presence of hypertension among these patients must be evaluated considering the significantly high presence of hypertensive adults in the country, which was 42.6% in 2016.17

Use of healthcare resources

The analysis of this admission-based database provides data on patients’ use of resources and an approximation to current disease management at the hospital level. Overall, patients’ hospitalisation data show a high prevalence of scheduled admissions, although the importance of emergency consultations is not minor as they reach 41.72% of total files. Most patients were admitted into neurology services, followed by paediatrics. Research arguments the need to establish a multidisciplinary approach to the disease, where all physicians involved are coordinated and aware of the disease course which could facilitate patient treatment and improve patients’ prognosis18; this would be especially relevant for the care of paediatric patients.

The average hospitalisation time, of ten days, is similar to findings in previous studies and has been mostly associated with managing respiratory complications,19 as many patients require persistent mechanical ventilation. This implicates that enormous changes in costs may appear derived from differences in disease severity, since prolonged hospitalisations account for larger medical costs. This can be observed in the disaggregated analysis of annual costs, where individual expenses reached figures distant from the total average. Thus, variations on admission costs over the years are not explained by an increase in patient or hospitalisation number and are extremely dependent on small oscillations in diagnosis-related groups that determine procedures costs and on individual patients requiring more specialised procedures, probably due to an increased degree of severity of the disease.

The annual cost of SMA at the hospital level in Spain, of €291 525, is not comparable to medical costs of €600 million that were estimated in the whole USA in 2010. However, it is a figure likely to increase once pharmaceutical expenses and other medical costs are considered. The annual cost per admission, of €6274, is not distant to that in children with SMA in the USA, where it ranged from around €5200 to €44 400, increasing with the presence of other complex chronic conditions.11 At a smaller scale, another study based on the US military healthcare system data estimated a cost of €42 300 per year,13 while in Germany the mean annual cost per patient was around €70 600.20 These figures were obtained considering a wider range of factors such as pharmaceutical treatment, travel expenses, informal care and other indirect costs that must be considered in Spain for upcoming resource allocation decisions.

The quantification of the cost that SMA represents for the healthcare system in terms of use of resources is vital for resource allocation and decision-making. Evidence-informed decision-making based on real-world data such as that extracted from the CMBD database has been vital to improve healthcare systems, as it has been outlined by the WHO.21 Disease burden evaluations have been used with this aim in multiple occasions in regions with distinct healthcare system frameworks.22–24 Herein, the impact of this study is limited by several factors including the lack of pharmaceutical data and the low specificity of ICD9-CM codes that impede an analysis per SMA type. Further research will be required in the country using the mentioned variables.

Conclusions

The rarity of SMA has limited the number of studies analysing the portion of population that is affected and how the disease is managed, including the medical costs associated with it. The analysis of 18 years of medical records allows a clearer analysis of patient characteristics and disease burden. Medical costs increase with length of stay and vary greatly with individual patient characteristics. This study highlights the importance of understanding patient characteristics and physicians’ management of the disease to establish more efficient protocols, including a multidisciplinary approach that involves neurologists, paediatric neurologists, orthopaedics and all physicians responsible for these patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JD contributed to the investigation by interpreting the economic situation of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in Spain and was a major contributor in the intellectual content revision. AM analysed SMA current situation in Spain, analysed and interpreted the statistical data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Data were anonymised prior to extraction and thus ethics committee approval and patient consent were not required for this study (law 14/2007, 3 July, of biomedical research, Spain).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1. Vaidya S, Boes S. Measuring quality of life in children with spinal muscular atrophy: a systematic literature review. Qual Life Res 2018;27:3087–94. 10.1007/s11136-018-1945-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spinal dystrophy association. Available: https://www.mda.org [Accessed 15 Feb 2019].

- 3. Haaker G, Fujak A. Proximal spinal muscular atrophy: current orthopedic perspective. Appl Clin Genet 2013;6:113–20. 10.2147/TACG.S53615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Russman BS. Spinal muscular atrophy: clinical classification and disease heterogeneity. J Child Neurol 2007;22:946–51. 10.1177/0883073807305673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Auvin S, Irwin J, Abi-Aad P, et al. The problem of rarity: estimation of prevalence in rare disease. Value Health 2018;21:501–7. 10.1016/j.jval.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kolb SJ, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy: a timely review. Arch Neurol 2011;68:979–84. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verhaart IEC, Robertson A, Wilson IJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q-linked spinal muscular atrophy - a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:124 10.1186/s13023-017-0671-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. López-Bastida J, Peña-Longobardo LM, Aranda-Reneo I, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in Spain. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:141 10.1186/s13023-017-0695-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farrar MA, Carey KA, Paguinto S-G, et al. Financial, opportunity and psychosocial costs of spinal muscular atrophy: an exploratory qualitative analysis of Australian carer perspectives. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020907 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Certificates of Discharge of the National Health System Register Claims database minimum basic data set (CMBD). Available: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/cmbdAnteriores.htm [Accessed 8 Oct 2018].

- 11. Cardenas J, Menier M, Heitzer MD, et al. High healthcare resource use in hospitalized patients with a diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (Sma1): retrospective analysis of the kids' inpatient database (kid). Pharmacoecon Open 2019;3:205–13. 10.1007/s41669-018-0093-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Armstrong EP, Malone DC, Yeh W-S, et al. The economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy. J Med Econ 2016;19:822–6. 10.1080/13696998.2016.1198355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liewluck T, Saperstein DS. Progressive muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin 2015;33:761–73. 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belter L, Cook SF, Crawford TO, et al. An overview of the cure SMA membership database: highlights of key demographic and clinical characteristics of SMA members. J Neuromuscul Dis 2018;5:167–76. 10.3233/JND-170292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mesfin A, Sponseller PD, Leet AI. Spinal muscular atrophy: manifestations and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:393–401. 10.5435/JAAOS-20-06-393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Catteruccia M, Colia G, Bonetti A, et al. Scoliosis is an inescapable comorbidity in SMA type II. A single center experience. Neuromuscul Disord 2017;27:S134–249. 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.06.153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Menéndez E, Delgado E, Fernández-Vega F, et al. Prevalence, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in Spain. Results of the Di@bet.es Study. Rev Esp Cardiol 2016;69:572–8. 10.1016/j.rec.2015.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord 2018;28:103–15. 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teynor M, Hou Q, Zhou J, et al. Healthcare resource use in patients with diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in Optum™ U.S. claims database (P4.158). Neurology 2017;88. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klug C, Schreiber-Katz O, Thiele S, et al. Disease burden of spinal muscular atrophy in Germany. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11:58 10.1186/s13023-016-0424-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Banta HD, European Advisory Committee on Health Research, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe . Considerations in defining evidence for public health: the European Advisory Committee on health research World Health organization regional office for Europe. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2003;19:559–72. 10.1017/s0266462303000515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spiers JA, Lo E, Hofmeyer A, et al. Nurse leaders' perceptions of influence of organizational restructuring on evidence-informed decision-making. Nurs Leadersh 2016;29:64–81. 10.12927/cjnl.2016.24805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morgan RL, Kelley L, Guyatt GH, et al. Decision-Making frameworks and considerations for informing coverage decisions for healthcare interventions: a critical interpretive synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;94:143–50. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pantoja T, Barreto J, Panisset U. Improving public health and health systems through evidence informed policy in the Americas. BMJ 2018;362 10.1136/bmj.k2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.