Abstract

Objective

Between 1998 and 2009 reported exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates in South African infants, aged 0–6 months, ranged from 6.2% to 25.7%. In 2011, the National Minister of Health shifted policy to promote ‘exclusive’ breast feeding for all women in South Africa irrespective of HIV status (Tshwane Declaration of Support for Breastfeeding in South Africa). This analysis examines early EBF prior to and through implementation of the declaration.

Setting

Data from the three South Africa national, cross-sectional, facility-based surveys, conducted in 2010, 2011–12 and 2012–13, were analysed. Primary health facilities (n=580) were randomly selected after a stratified multistage probability proportional-to-size sampling to provide valid national and provincial estimates.

Participants

A national sample of all infants attending their 6 weeks vaccination at selected facilities. The number of caregiver-infant pairs enrolled were 10 182, 10 106 and 9120 in 2010, 2011–12, and 2012–13, respectively.

Primary outcome measure

Exclusive breast feeding as measured using structured 24 hours recall plus prior 7 days (8 days inclusive prior to day interview) and WHO definition.

Results

The adjusted OR comparing EBF prevalence in 2011–12 and 2012–13 with 2010 were 2.08 and 5.51, respectively. Mothers with generally higher socioeconomic status, HIV-positive, unplanned pregnancy, primipara, postcaesarean delivery, resided in certain provinces and women who did not receive breastfeeding counselling had significantly lower odds of EBF.

Conclusion

With what seemed to be an intransigently low EBF rate since 1998, South Africa saw an increase in early EBF for infants aged 4–8 weeks from 2010 to 2013, coinciding with a major national breastfeeding policy change. These increases were seen across all provinces and subgroups, suggesting a population-wide effect, rather than an increase in certain subgroups or locations. While these increases in EBF were significant, the 59.1% prevalence is still below desired levels of early EBF. Further improvements in EBF programmes are needed.

Keywords: breast feeding, national feeding policy, south africa, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The data were from a nationally representative survey of infants presenting at primary facilities for immunisation services which provides robust national estimates.

Infants who did not come for immunisation or had already died by 4–8 weeks of age or attended a private hospital/clinic for care were not included in the sample suggesting a possible selection bias.

The study used structured validated questionnaires and WHO recommended infant feeding definitions.

Caregivers may have not accurately reported infant feeding practices due to recall bias.

The comparison to the Tshwane Declaration of Support for Breastfeeding in South Africa policy change is ecologic, therefore no causal inference can be confirmed.

Introduction

South Africa is reported to have one of the lowest exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates in Africa. National and regional studies conducted between 1998 and 2009 reported EBF rates in South African infants, aged 0–6 months ranging from 6.2% to 25.7% (table 1).1–7 Although questions, settings and methods varied across these studies, all found that the EBF rate in South Africa remained consistently low in the 1990s through 2009.

Table 1.

South African exclusive breast feeding (EBF) rates (%) 1998–2009

| Study | Time period | Location | Recall period | 1998 | 2003 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

| DHS1 2 | 0–3 months | National | 24 hours | 10.4 (n=312) |

11.2* (n=55) |

|||

| DHS1 2 | 0–5 months | National | 24 hours | 7.0 (n=505) |

8.3 (n=194) |

|||

| Good start 13 4 | 7 weeks | KZN, EC, WC | 24 hours | HIV+: 13.6 (n=493) HIV−: 12.2 (n=181) |

||||

| Good start 13 4 | 3 months | KZN, EC, WC | 24 hours | HIV+: 7.2 (n=487) HIV−: 2.8 (n=178) |

||||

| PROMISE-EBF5 | 3 months | KZN, WC | 24 hours | 6.2 (n=485) |

||||

| HSRC6 | 0–6 months | National | Unknown | 25.7 (n=508) |

||||

| Good start 27 | 3 months | KZN—Durban | 24 hours | 14.9 (n=1693) |

*Data for infants <2 months.

DHS, Demographic Health Survey; EC, Eastern Cape province; HIV+, HIV positive; HIV−, HIV negative; HSRC, Human Sciences Research Council; KZN, KwaZulu-Natal province; WC, Western Cape province.

Reasons for these low EBF rates have been examined across various settings. The South African HIV epidemic has no doubt been a contributing factor for avoiding breast feeding or early breastfeeding cessation; however, low EBF rates predate the increased focus on HIV since 2000.2 The use of formula by health service providers to treat malnutrition and for babies of mothers living with HIV, has been cited as providing mixed messages to communities about the benefits of breast feeding compared with formula milk, and about EBF.8 Cultural norms for early mixed feeding, urbanisation, stigma in HIV-positive mothers and mothers returning to work have all been cited as challenges to EBF.9–11 Consequently, EBF messaging was not consistently supported by frontline health workers, programme managers or policy makers at the height of the HIV epidemic, between 2001 and 2011.

In 2011, the National Minister of Health held a consultation on breast feeding, which lead to a clear shift in national policy to promote EBF for all women in South Africa irrespective of HIV status, through the release of the Tshwane Declaration of Support for Breastfeeding in South Africa (Tshwane Declaration).12 13 By September 2012, free formula milk for mothers living with HIV was withdrawn from the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) programme and EBF messaging for front line workers was emphasised as a policy priority.13

This analysis uses data from the three national South Africa National PMTCT surveys conducted to measure early PMTCT effectiveness14–16 and aims to examine early EBF rates at 4–8 weeks post partum, in 2010 prior to the Tshwane Declaration, in 2011–12 during the policy transition period and 2012–13 after complete implementation of the Tshwane Declaration.

Methods

Data from three national, cross-sectional, facility-based surveys, South African PMTCT Evaluations (SAPMTCTEs), conducted in 2010, 2011–12 and 2012-1314–16 were analysed. These surveys aimed to capture a national sample of all infants attending their 6 weeks vaccination, regardless of HIV status. Known and unknown HIV-exposed and HIV-unexposed infants, as well as PMTCT participants and non-participants were included in these three surveys, such that the sample used for this infant feeding analysis represents a nationally representative sample of HIV-exposed and HIV-unexposed infants.

These surveys were conducted in public primary healthcare (PHC) and community health centres (CHC) offering immunisation services in all nine provinces. This methodology was chosen as uptake of 6 weeks immunisation in South Africa was >99%, according to the 2007 District Health Information System (DHIS). Stratified multistage probability sampling proportional to size, followed by random sampling of facilities and consecutive or systematic sampling of participants (caregivers with infants aged 4–8 weeks receiving their first diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus immunisation) was conducted. The methods for the 2011–12 and 2012–2013 surveys were the same as described in 2010.14–16 The sampling frame and selected facilities were identical between 2011–12 and 2012–13, except for four clinic replacements due to shifting of services or clinic closure for maintenance.

Immunisation data from the 2007 DHIS were used to quantify the number of children that could be expected within PHC/CHC facilities over a period of time. These were then stratified by size. Sample size was calculated so that valid national and provincial level estimates of MTCT could be ascertained. In the first stage, facilities (primary sampling units) were randomly sampled proportional to size within each stratum. This resulted in 34–79 facilities per province, 580 in total. In the second-stage, caregiver/infant pairs were consecutively or randomly selected from facilities (depending on facility size). The desired sample size was 12 200 infants aged 4–8 weeks, per survey to produce national and provincial estimates. Hospitals and mobile clinics, very sick infants or infants aged <4 weeks or >8 weeks were excluded.

Maternal/caregiver interviews were conducted and infant dried blood spots (iDBS) were drawn after receiving consent from caregivers for study participation. Data were collected using low cost cellular telephones and interview data were uploaded into a web-based database console, in real-time. Interviews gathered data on maternal sociodemographics, antenatal and postnatal care, mother’s reported HIV status and PMTCT services. Infant feeding information was collected using structured recall documenting whether the infants received a particular food or fluid during the past 24 hours and the 7 days prior (8 days inclusive prior to day of interview). Exclusive breast feeding was defined as giving the infant no other food or drink (not even water) except breast milk (including milk expressed or from a wet nurse), but allowed the infant to receive prescribed medicines.17

This analysis includes all infants for which there was consent and a valid questionnaire, with or without an iDBS and regardless of HIV exposure or HIV infection status. Analysis was weighted for sample realisation and at provincial level proportional to the live birth distribution of South Africa. The main outcome variable of interest gathered from the three surveys was the proportion of infants exclusively breast fed at 4–8 weeks post partum. We conducted logistic regression to examine if these factors were associated with EBF: maternal—age, education, marital status, parity, employment and HIV status; household—type, water source, fuel for cooking and toilet; food insecurity; planned pregnancy, antenatal care—initiation (trimester) and attendance (4+ visits); delivery mode and receipt of breastfeeding counselling: (asked as “During pregnancy did you ever discuss with anyone at the clinic what the best way for you to feed your baby”); child—sex and age in weeks.

The analytic dataset included 3 years (2010–2013) of data from the three consecutive cross-sectional nationally representative SAPMTCTEs. We used survey statistics in STATA SE, V.15 for the calculation of the SEs of the survey estimates to account for the stratification, sample weights and the multistage design.

Survey statistics were used to report two-way table descriptive statistics, which included proportions and 95% CIs. Univariate logistic regressions (survey) were run on the binary EBF outcome at 4–8 weeks controlling for year. The first multiple logistic regression model which included 19 possible categorical predictors (including year) were examined based on known predictors of EBF from the literature. Predictors were retained if at least one category was significant at 5% level, which resulted in a final multiple regression model with 15 categorical predictors. Interaction effects between year and other predictor variables were also examined; from this only the interaction effect of antenatal breastfeeding counselling receipt and year was retained in the final model. All results were reported as ORs with 95% CIs (significance at 5% level).

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the design of this study.

Results

The number of caregiver-infant pairs enrolled in 2010, 2011–12, and 2012–13 were 10 182, 10 106 and 9120, respectively. National EBF rates at 4–8 weeks of age were 22.9% (95% CI 21.5 to 24.3) in 2010, 35.7% (95% CI 33.9 to 37.6) in 2011–12 and 59.1% (95% CI 57.4 to 60.7) in 2012–13, p≤0.001. All nine provinces showed similar statistically significant increasing EBF trends between 2010 and 2012–13. (Table 2).

Table 2.

South African and provincial EBF rates at 6 (4–8) weeks post partum 2010, 2011-2012 and 2012-2013

| 2010 n=10 182 |

2011–12 n=10 106 |

2012–13 n=9120 |

|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Eastern Cape | 15.5 (12.0 to 19.8) | 24.8 (21.0 to 29.1) | 53.8 (49.0 to 58.5) |

| Free State | 16.1 (14.1 to 18.2) | 33.3 (30.5 to 36.3) | 53.3 (48.7 to 57.9) |

| Gauteng | 23.2 (20.2 to 26.5) | 36.4 (31.6 to 41.6) | 65 (61.2 to 68.6) |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 33.7 (30.2 to 37.4) | 46.6 (43.0 to 50.2) | 60.4 (55.9 to 64.6) |

| Limpopo | 19.5 (16.1 to 23.4) | 21.3 (18.0 to 24.9) | 47.9 (43.0 to 52.8) |

| Mpumalanga | 15.9 (13.1 to 19.2) | 47.3 (41.2 to 53.5) | 65 (61.7 to 68.2) |

| Northern Cape | 22.1 (18.8 to 25.8) | 30.9 (26.6 to 35.4) | 61.7 (57.4 to 65.9) |

| Northwest | 24.3 (20.7 to 28.2) | 30.4 (26.8 to 34.2) | 65.4 (60.6 to 69.8) |

| Western Cape | 17.9(15.3 to 20.8) | 36 (31.2 to 41.1) | 54.9 (49.8 to 59.8) |

| South Africa* | 22.9(21.5 to 24.3) | 35.7 (33.9 to 37.6) | 59.1 (57.4 to 60.7) |

*Trends for year, adjusting for province significant, p<0.001.

EBF, exclusive breast feeding.

The crude OR for EBF comparing 2011–12 and 2012–13 with 2010 was 1.88 (95% CI 1.70 to 2.07) and 4.87 (95% CI 4.40 to 5.38), respectively (table 3). The OR comparing EBF in 2010 to the subsequent time period (2011–12 or 2012–2013) is adjusted just for the individual variable listed, such as maternal marital status (all categories, details of variable categories can be found in table 4)). In this univariate analysis (table 3), the EBF by year ORs did not change by >10% for any of the examined variables, suggesting that these increases were seen across all regions and population sub-groups.

Table 3.

Covariates influence on EBF increase, 2010 compared with 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 (univariate logistic regression analysis)*

| Variable | 2011–2012 OR for EBF (compared with 2010) |

2012–13 OR for EBF (compared with 2010) |

| EBF OR (crude) | 1.88 (95% CI 1.70 to 2.07) | 4.87 (95% CI 4.40 to 5.38) |

| EBF OR adjusted for each individual variable in univariate analysis | ||

| Maternal HIV status | 1.87 | 4.93 |

| Maternal age | 1.88 | 4.86 |

| Maternal education | 1.89 | 4.92 |

| Maternal marital status | 1.88 | 4.87 |

| House type | 1.88 | 4.90 |

| Water source | 1.88 | 4.87 |

| Toilet type | 1.87 | 4.86 |

| Fuel source | 1.88 | 4.87 |

| Food insecurity | 1.85 | 4.87 |

| Infant gender | 1.88 | 4.87 |

| Infant age | 1.85 | 4.77 |

| Antenatal breastfeeding counselling | 1.94 | 4.80 |

The OR in this table are the OR for EBF adjusted for the individual variable, eg, infant gender or infant age as categorised in table 4. We are not comparing OR of EBF by maternal HIV status (eg, positive or negative), we are comparing the crude OR for EBF by year with the OR for EBF by year adjusted for maternal HIV status to examine for potential confounding by maternal HIV status. This OR is then compared with the crude OR to see if the effect estimate (OR of EBF by year) changes by ±10% suggesting potential confounding of OR by year due to the third variable (eg, variables listed in the first column). Note for 2011–2012 compared with 2010 an adjusted OR of <1.69 or >2.07 would reflect a >10% difference in OR; while for 2012–13 an adjusted OR of <4.38 or >5.36 would reflect a >10% difference in OR. None of the univariate adjusted estimates for EBF by year are outside of these ranges suggesting confounding of the OR by year is unlikely due to the individual covariate analysed. Total observations: 29 981.

EBF, exclusive breast feeding.

Table 4.

Full adjusted multivariate logistic regression model for predictors of EBF at 4–8 weeks post partum, 2010–2013

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI* |

| Year (ref: 2010) | ||

| 2011–12 | 2.08 | 1.87 to 2.32 |

| 2012–13 | 5.51 | 4.94 to 6.15 |

| Province (ref: EC) | ||

| FS | 1.22 | 0.99 to 1.50 |

| GP | 1.70 | 1.38 to 2.09 |

| KZN | 2.15 | 1.76 to 2.64 |

| LP | 0.97 | 0.77 to 1.22 |

| MP | 1.63 | 1.31 to 2.03 |

| NC | 1.33 | 1.07 to 1.66 |

| NW | 1.49 | 1.21 to 1.84 |

| WC | 1.30 | 1.03 to 1.64 |

| Mother age, years (ref: <20 years) | ||

| 20–34 | 1.07 | 0.99 to 1.61 |

| 35–50 | 1.12 | 1.01 to 1.25 |

| Mother education (ref: no education) | ||

| Grade 1–7 | 1.00 | 0.83 to 1.21 |

| Grade 8–12 | 0.86 | 0.72 to 1.03 |

| Tertiary | 0.62 | 0.50 to 0.77 |

| Parity (ref: primipara) | ||

| Multipara | 1.16 | 1.09 to 1.23 |

| Mother employment (ref: employed) | ||

| Other income | 1.53 | 1.42 to 1.65 |

| No income | 1.53 | 1.02 to 2.31 |

| HIV status (ref: negative) | ||

| Positive | 0.66 | 0.61 to 0.71 |

| Do not know | 0.74 | 0.56 to 0.99 |

| House type (ref: brick) | ||

| Informal/Wood | 1.09 | 1.00 to 1.19 |

| Traditional/Mud | 1.20 | 1.01 to 1.42 |

| Water source (ref: piped in house/yard) | ||

| Not piped in house/yard | 0.84 | 0.75 to 0.93 |

| Toilet (ref: indoor flush) | ||

| Pit latrine | 1.19 | 1.07 to 1.32 |

| Portable | 0.89 | 0.59 to 1.33 |

| Other | 1.55 | 0.80 to 3.02 |

| None | 1.03 | 0.82 to 1.29 |

| Fuel for cooking (ref: electricity) | ||

| Wood/Coal | 0.85 | 0.74 to 0.98 |

| Other | 0.96 | 0.57 to 1.62 |

| Food insecurity (ref: yes) | ||

| No | 1.13 | 1.04 to 1.23 |

| Do not know | 1.65 | 1.20 to 2.25 |

| Planned pregnancy (ref: yes) | ||

| No | 0.93 | 0.88 to 0.99 |

| Delivery mode (ref: vaginal) | ||

| Caesarean | 0.84 | 0.78 to 0.90 |

| Infant age, weeks (ref: 4 weeks) | ||

| 5 | 0.82 | 0.66 to 1.02 |

| 6 | 0.92 | 0.75 to 1.24 |

| 7 | 0.86 | 0.71 to 1.05 |

| 8 | 0.69 | 0.55 to 0.86 |

| Antenatal breastfeeding counselling (ref: yes) | ||

| No | 0.74 | 0.63 to 0.88 |

| Antenatal breastfeeding counselling by year (ref: yes in 2010)† | ||

| No ANC counselling in 2011–12 | 0.62 | 0.49 to 0.80 |

| No ANC counselling in 2012–2013 | 0.66 | 0.52 to 0.84 |

*Bold indicate 95% CI does not cross null (1.0); total observations: 29 288.

†This measures the multiplicative interaction of ANC breastfeeding counselling by year, hence the referent is a combination of having ANC breastfeeding counselling compared with the combination of no ANC breastfeeding counselling in each subsequent year.

ANC, antenatal care; EBF, exclusive breast feeding.

In the full logistic model including all variables (data not shown), the EBF by year estimates did not change by >10% suggesting again no confounding due to examined covariates. However, in the final logistic model, including an interaction term for year and counselling (table 4), the annual EBF differences did change by just over 10% (2.08 in 2011–2012 and 5.51 in 2012–2013), suggesting a potential confounding effect.

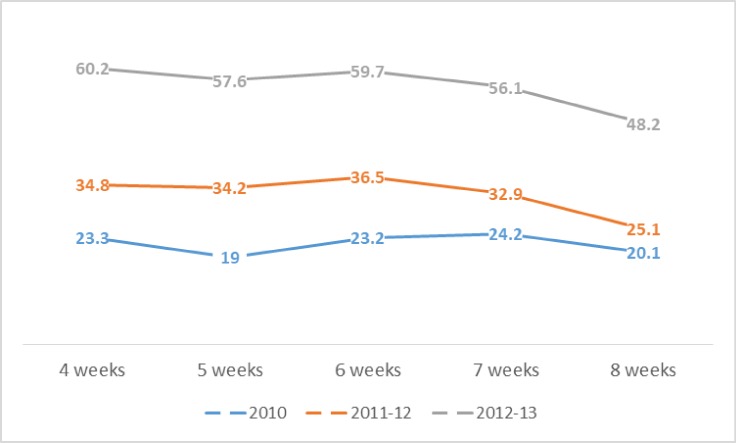

In the full multivariable model (table 4), mothers with younger age, mothers who were HIV-positive, had an unplanned pregnancy, primipara, had a caesarean delivery and who did not receive breastfeeding counselling had lower odds of EBF. Socioeconomic status influence showed mixed results with mothers with tertiary education, formal brick housing, indoor flush toilet and employed mothers having lower odds of EBF, while piped water in the house or yard and electricity as fuel source had higher odds. EBF showed significant decline by the eighth week of age (table 4, figure 1).

Figure 1.

Exclusive breastfeeding rates by infant age in weeks by year, 2010–2013.

Discussion

Exclusive breastfeeding rates

This study suggests that EBF in South Africa at national level and across all nine provinces increased significantly between 2010 and 2012–13. Similar increases in EBF have been recorded in local studies in KwaZulu-Natal18 and Gauteng.19 While, the KwaZulu-Natal study was in the context of an improved EBF counselling programme, it is consistent with improved programme efforts post-Tshwane.

The South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES)20 data do not suggest an increase. The SANHANES rate reported for 2012 was 12.7% for infants <2 months of age, this is relatively similar to the 2003 South African Demographic and Health Survey (SADHS) of 11.2%.2 Possible differences between our study and the SANHANES is in the way data were collected. We used an 8-day feeding recall in this study; however, SANHANES had no specified time period for the collection of their feeding information (mix of ‘from birth’ and ‘current’ questions).

The most recent SADHS in 2016 also showed an increase in EBF to 32% for infants <6 months, with EBF at 44% at 0–1 month and 28.2% at 2–3 months (similar time frames as this study).21 SADHS used a 24 hours recall and used the same definition of EBF as used in the SAPMTCTE. It should be noted that a major difference in SADHS and our survey is that one is a household survey and one facility based. Additionally, SADHS included only 115 infants aged <1 month. This is a very small sample size, and results from SADHS should be interpreted with caution. Our use of 8-day recall and large sample sizes suggest potentially robust estimates.22 23 Nevertheless, many studies use longer periods of measurement such as 0–6 months, such that our estimates of early EBF at 4–8 weeks would be expected to be higher. However, while the SAPMTCE EBF rates are higher than SADHS, the relative increase in EBF across years (1998, 2003–2016), and rapidly decreasing EBF by age in the first few months of the infant’s life in SADHS are similar to the SAPMTCTE data.

Changes in national and provincial programmes after Tshwane Declaration

Our data and analytic framework are different from other studies as we measured EBF immediately before, during and immediately after a major national infant feeding policy shift. Our results suggest that this policy shift may be responsible in part for the rapid increases seen in EBF that we found, which are also confirmed by the latest SADHS.

Our time series is an ecologic comparison, measured in the context of a national policy change in 2011, thus causal inference is difficult to establish. However, the policy did lead to major rapid changes in many aspects of infant feeding guidance and programmes across South Africa. For example, after adoption of the Tshwane Declaration of Support for Breastfeeding in South Africa, which committed to and declared ‘South Africa as a country that actively promotes, protects and supports EBF as a public health intervention to optimise child survival, regardless of the mother’s HIV status’.12 Guidelines on Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) were revised and the issuing of free infant formula was stopped in a phased out process from 1 April 2012 with full withdrawal by September 2012. From April 2012, no new mothers with newborns were to be issued with free infant formula.13 South Africa enforced into law the Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes.24 Letters were sent to provincial Heads of Health requesting that the ‘The Tshwane Declaration of Support for Breastfeeding in South Africa’12 and the ‘Policy Directive for the Implementation of the Declaration on Support of Exclusive Breastfeeding and Revised Guidelines on Infant and Young Child Feeding for Women with HIV’13 be brought to the attention of all health facilities for implementation.

Following this national guidance, all provinces developed revised infant and young child feeding policies and implementation plans for 2012–2013. A review of these policies conducted by the study team found the following common components: IYCF policy consistent with the national policy (eg, promotion of EBF for all children under 6 months of age), withdrawal of free formula from the PMTCT programme (eg, no new formula as of 1 April 2012 with all free formula withdrawn by end of 2012), training programmes for health workers and facility managers, implementation and strengthening of the Mother Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (MBFHI), implementation of Kangaroo Mother Care, implementation of mother’s milk banks and a variety of communication strategies, such as outdoor advertising (eg, billboards), radio programming, print advertising, Information, Education and Counselling (IEC) materials, community outreach activities and training of community health workers in breastfeeding promotion and support.

In addition to formal national and provincial communication plans, and in particular due to the withdrawal of free formula from the PTMCT programme, the Tshwane Declaration saw national and local media attention to the new policy and the evidence to support EBF in South Africa through reports in most major newspapers, radio and television news and online health news sites.25 The media coverage may have increased awareness about the benefits of EBF. Other extended effects also found in the policy review include the resurgence in the MBFHI as the number of MBHFI accredited hospitals increased from 178 in 2005 to 382 in 2014–2015.

The variety of implementation strategies included in the provincial plans noted above are consistent with recent meta-analyses of health system strategies to increase EBF. A 2015 meta-analysis26 found the following interventions to significantly increase EBF: baby friendly (health facility) support, counselling in health facilities, training of health workers, counselling and support in communities (individual or in groups) and integrated mass media and counselling. Another meta-analysis reported in 201627 concurred with the 201526 findings and also found that using a combination of approaches showed an even higher impact on EBF. These findings suggest that the implementation of IYCF in South Africa post the Tshwane Declaration, which used many of these proven strategies primarily as a combination of approaches, further strengthens our argument that changes in national policy which were then implemented at all levels is one plausible contributor for the rapid increase in EBF found between 2010 and 2012–2013.

Groups at risk for lower EBF

Our results show that the similar increases in EBF were found across all subgroups of mothers (table 3), however results do indicate some groups were still at risk for lower odds of EBF rates (table 4). Our data suggest that generally higher socioeconomic status and employed mothers were less likely to EBF. This inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and EBF is commonly seen in low-income and middle-income countries.28 However, this finding was not consistent across all proxy measures for socioeconomic status as those mothers without electricity and piped water were less likely to EBF, which is a concern as lack of electricity and piped water have been found to be substantial risk factors for mortality when the infant is formula feeding.8

We also found younger mothers to have lower EBF. Findings on young maternal age and association with EBF in Africa have seen mixed results.29–31 Primiparas were also seen to have lower EBF, which is consistent with the finding on younger mothers. However, again results in the literature were mixed. A study in Tanzania31 found no difference in EBF across parity groups, while studies in Nigeria30 and Ethiopia28 found an opposite result of higher EBF in lower parity mothers. These mixed results across age and parity may reflect local social and cultural norms across countries. For South Africa targeting interventions to younger first-time mothers might help to further increase EBF. Unintended pregnancy also was associated with lower EBF. The literature is sparse on this potential association, one study in Ghana32 describes shorter breastfeeding duration for mothers with unintended pregnancy and in a qualitative study in Kenya33 respondents cited unintended pregnancy as a factor which influenced their infant feeding. Further study is needed on the relation between unintended pregnancy and EBF.

Consistent with the literature we also saw a drop in EBF in the older infant age group at 8 weeks across all years of the study.21 31 This is consistent with the literature and other South African studies. This drop of in EBF prior to age 6 months remains an ongoing concern.

Particularly encouraging is that the strongest predictor of higher EBF was antenatal breastfeeding counselling both individually and in interaction across years, which is consistent with recent meta-analyses,26 27 suggesting that programme managers should assure ongoing antenatal breastfeeding counselling across all facilities and communities.

Limitations

Limitations of the source cross-sectional survey must be recognised. The data were primary facility-based using infants presenting for immunisation services. Infants who did not come for immunisation or had already died by 4–8 weeks of age or attended private hospital/clinic for care were not included in the sample suggesting a possible selection bias. Mothers may have not accurately reported infant feeding practices due to recall bias. Also, this analysis only examines early (4–8 weeks) EBF, rates and factors influencing breast feeding can vary based on the age of the infant. Comparison to the Tshwane policy change is an ecologic analysis, and as such it is difficult to perfectly estimate the average causal effect of this single policy change as other factors may be operational.

Public health implications

With what seemed to be an intransigently low EBF rate since 1998, South Africa saw a remarkable increase in early EBF (4–8 weeks) from 2010 to 2013 coinciding with a major national infant feeding policy change. These increases were seen across all provinces and subgroups, suggesting a population wide effect, not just an increase in certain subgroups or locations.

While these increases in EBF were significant, and a huge step towards changing the tide of poor infant feeding in South Africa, the 59.1% prevalence is still below desired levels of early EBF suggesting that much remains to be done to further improve infant feeding practices. The results of this study suggest several predictors of EBF which could guide future programmatic interventions to further improve EBF rates, such as greater attention to vulnerable groups, such as young women and first time mothers, and assuring antenatal breastfeeding counselling with a combination of approaches as suggested in recent meta-analyses.26 27

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DJ and AG were principal investigators for the three national surveys used for this analysis. SS and CL analysed the data. TD and SB were co-investigators and members of the steering committee for the three national surveys used in this analysis. DJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and is corresponding author. All authors had access to study data, contributed to writing and editing the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This manuscript has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of (1U2GPS001137-01 thru 04) and UNICEF. DJ and TD were also supported by the South African National Research Foundation.

Disclaimer: The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC or UNICEF.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the South African Medical Research Council (EC09-002) and was reviewed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (IRB identifier: FWA00002753 Cooperative agreement number: U2G/PS001137·0 1) according to the human research protection procedures. All mothers/caregivers signed informed consent prior to study participation. Laboratory results were returned to mothers through routine services. At all visits, mother and infants not in routine care were referred to routine services. No personal identifiers were included in the interview and laboratory study databases.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Department of Health, Medical Research Council, OrcMacro South Africa demographic and health survey 1998. Pretoria: Department of Health, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health, Medical Research Council, OrcMacro South Africa demographic and health survey 2003. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colvin M, Chopra M, Doherty T, et al. . Single-Dose nevirapine regimen in the South African national prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme is effective in reducing early transmission of HIV-1. Bulletin of WHO 2007;85:466–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goga AE, Doherty T, Jackson DJ, et al. . Infant feeding practices at routine PMTCT sites, South Africa: results of a prospective observational study amongst HIV exposed and unexposed infants - birth to 9 months. Int Breastfeed J 2012;7:4 10.1186/1746-4358-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tylleskär T, Jackson D, Meda N, et al. . Exclusive breastfeeding promotion by peer counsellors in sub-Saharan Africa (PROMISE-EBF): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:420–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60738-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shisana O, Simbayi LC, et al. , Dinh TH and SABSSM III Implementation Team . South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2008: the health of our children. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tomlinson M, Doherty T, Ijumba P, et al. . Goodstart: a cluster randomised effectiveness trial of an integrated, community-based package for maternal and newborn care, with prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a South African township. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:256–66. 10.1111/tmi.12257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doherty T, Sanders D, Goga A, et al. . Implications of the new who guidelines on HIV and infant feeding for child survival in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:62–7. 10.2471/BLT.10.079798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lazarus R, Struthers H, Violari A. Promoting safe infant feeding practices - the importance of structural, social and contextual factors in Southern Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18037 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ijumba P, Doherty T, Jackson D, et al. . Social circumstances that drive early introduction of formula milk: an exploratory qualitative study in a peri-urban South African community. Matern Child Nutr 2014;10 10.1111/mcn.12012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agunbiade OM, Ogunleye OV. Constraints to exclusive breastfeeding practice among breastfeeding mothers in Southwest Nigeria: implications for scaling up. Int Breastfeed J 2012;7:5 10.1186/1746-4358-7-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. South African National Department of Health (NDoH) The Tshwane Declaration of support for breastfeeding in South Africa. S Afr J Clin Nutr 2011;24. [Google Scholar]

- 13. South African National Department of Health (NDoH) Policy directive for the implementation of the South African Declaration on support of exclusive breastfeeding and revised guidelines on infant and young child feeding. Pretoria: NDOH, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goga AE, Dinh T-H, Jackson DJ, et al. . First population-level effectiveness evaluation of a national programme to prevent HIV transmission from mother to child, South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:240–8. 10.1136/jech-2014-204535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goga AE, Dinh T-H, Jackson DJ, et al. . Population-Level effectiveness of PMTCT option A on early mother-to-child (MTCT) transmission of HIV in South Africa: implications for eliminating MTCT. J Glob Health 2016;6:020405 10.7189/jogh.06.020405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goga AE, Jackson DJ, Singh M. Lombard C for the SAPMTCTE Study Group. early (4-8 weeks postpartum) population-level effectiveness of who PMTCT option a, South Africa, 2012-2013. Available: http://www.mrc.ac.za/sites/default/files/files/2016-07-12/SAPMTCTEReport2012.pdf

- 17.Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. Part I: Definitions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henriques S. South Africa improves exclusive breastfeeding monitoring using nuclear technique. IAEA Bulletin 2015;56:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Siziba L, Jerling J, Hanekom S, et al. . Low rates of exclusive breastfeeding are still evident in four South African provinces. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015;28:170–9. 10.1080/16070658.2015.11734557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shisana O, Labadarios D, et al. , SANHANES-1 Team . South African National health and nutrition examination survey (SANHANES-1. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South Africa Medical Research Council (SAMRC) and ICF . South Africa demographic and health survey 2016: key indicators, Pretoria, South Africa and Rockville Maryland USA: NDoH, STATs SA, SAMRC, and ICF, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fenta EH, Yirgu R, Shikur B, et al. . A single 24 h recall overestimates exclusive breastfeeding practices among infants aged less than six months in rural Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J 2017;12:36 10.1186/s13006-017-0126-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aarts C, Kylberg E, Hörnell A, et al. . How exclusive is exclusive breastfeeding? A comparison of data since birth with current status data. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:1041–6. 10.1093/ije/29.6.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. UNICEF and WHO welcome South Africa’s new regulations on infant foods. Pretoria: UNICEF/WHO Afro. Available: https://www.afro.who.int/news/unicef-and-who-welcome-south-africas-new-regulations-infant-foods [Accessed 21 May 2019].

- 25. Give baby the best – Breastmilk. Saturday Star/IOL news. Available: https://www.iol.co.za/saturday-star/give-baby-the-best-breast-milk-1136703 [Accessed 13 Sep 2011].

- 26. Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Sankar MJ, et al. . Interventions to improve breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:114–34. 10.1111/apa.13127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, et al. . Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016;387:491–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. . Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016;387:475–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mekuria G, Edris M. Exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in Debre Markos, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J 2015;10:1 10.1186/s13006-014-0027-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uchendu UO, Ikefuna AN, Emodi IJ. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding among mothers seen at University of Nigeria teaching Hospital, Enugu. South African journal of child health 2009;3:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maonga AR, Mahande MJ, Damian DJ, et al. . Factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding among women in Muheza district Tanga northeastern Tanzania: a mixed method community based study. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:77–87. 10.1007/s10995-015-1805-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chinebuah B, Pérez-Escamilla R. Unplanned pregnancies are associated with less likelihood of prolonged breast-feeding among primiparous women in Ghana. J Nutr 2001;131:1247–9. 10.1093/jn/131.4.1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kimani-Murage EW, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, et al. . Factors affecting actualisation of the who breastfeeding recommendations in urban poor settings in Kenya. Matern Child Nutr 2015;11:314–32. 10.1111/mcn.12161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.