Abstract

Introduction

Choosing Wisely, an international effort to reduce low value care worldwide, considers communication between clinicians and patients during routine clinical encounters a key mechanism for change. In Australia, Choosing Wisely has developed a 5 Questions resource to facilitate better conversations. The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of the Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions resource and a video designed to prepare patients for question-asking and participation in shared decision-making on (a) self-efficacy to ask questions and participate in shared decision-making, (b) intention to participate in shared decision-making and (c) a range of secondary outcomes. The secondary aim of this study is to determine whether participants’ health literacy modifies the effects of the interventions.

Methods and analysis

We will use 2×2×2 between-subjects factorial design (preparation video: yes, no × Choosing Wisely 5 Questions resource: yes, no × health literacy: adequate, inadequate). Participants will be recruited by an online market research company, presented with a hypothetical non-specific low back pain scenario, and randomised to study groups stratified by health literacy. Quantitative primary and secondary outcome data will be analysed as intention-to-treat using appropriate regression models (ie, linear regression for continuous outcomes, logistic regression for dichotomous categorical outcomes).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number: 2018/965). The results from this work will be disseminated through peer-reviewed international journals, conferences and updates with collaborating public health bodies. Resources developed for this study will be made available to patients and clinicians following trial completion.

Trial registration number

This trial has been registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (trial number: 376477) and the stage is Pre-results.

Keywords: patient participation, decision making, shared decision making, health literacy, question prompt list, medical overuse

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to assess the relative impact of the Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions resource, both alone and in combination with an additional video intervention designed to support and build patients’ confidence to ask questions compared with no intervention, and explore whether health literacy modifies the impact of interventions.

We will randomly allocate participants, conceal allocation, blind study statisticians and aim to recruit 1432 participants to achieve at least 80% power.

The main limitation of this study is reduced ecological validity and the limited generalisability of the findings due to (a) online recruitment and use of ‘healthy volunteers’, (b) the use of a hypothetical scenario and (c) delivering the interventions in a way that diverges from how they would be/are delivered in the real world.

However, this design allows us to achieve a high response and follow-up rate with adequate representation of people with limited health literacy in a factorial design requiring a large sample.

The measure of health literacy used in this study focuses on functional health literacy, but enables automatic scoring and categorisation of participants in an online setting.

Unnecessary and potentially harmful services account for a significant proportion of total health expenditure.1 The need to eliminate unnecessary medical care, decrease waste and reduce overdiagnosis has received increasing attention from health systems in the past decade. One initiative that has gained momentum worldwide is Choosing Wisely.2 Launched in April 2012 by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation, the Choosing Wisely campaign has now been adapted and implemented in more than 20 countries worldwide. The campaign seeks to encourage clinicians and patients to talk about medical tests and procedures that may be unnecessary, and in some instances, can cause harm.2 While acknowledging that it is often challenging to have conversations about unnecessary tests and treatments, leaders of the campaign consider communication between clinicians and patients during routine clinical encounters a key mechanism for change.2

As part of the original Choosing Wisely campaign, Consumer Reports (an independent non-profit product-testing organisation) partnered with the ABIM Foundation and developed five questions for patients to ask healthcare providers to support better conversations about unnecessary tests, medications and procedures.3 The questions are publically available and have been promoted for use nationally and internationally. The five questions were adopted by Choosing Wisely Australia (with some minor phrasing changes; see box 1) and have been disseminated in several forms and languages, including as a one-page downloadable resource, ‘5 Questions to Ask Your Doctor’ (hereafter referred to as the 5 Questions Resource), that lists the questions and provides additional guidance in their rationale and use (see online supplementary appendix A). Annual evaluation surveys conducted by Choosing Wisely Australia suggested that, in 2015 and 2016, 8% of healthcare consumers were aware of the 5 Questions Resource and, in 2017, it was the organisation’s most commonly downloaded material (4).

bmjopen-2019-033126supp001.pdf (64.5KB, pdf)

Box 1. The choosing Wisely Australia 5 questions.

Do I really need this test, treatment or procedure?*

What are the risks?

Are there simpler, safer options?

What happens if I don't do anything?

What are the costs?†

NPS Medicinewise Ltd. Reproduced with permission. Visit www.choosingwisely.org.au.

* Original Consumer Reports question: Do I really need this test or procedure?

† Original Consumer Reports question: How much does it cost?

The 5 Questions Resource has been promoted for its ‘potential to facilitate better conversations between healthcare providers and consumers’.4 However, it has yet to be formally evaluated, and the precise expected mechanism of action for its effect on the use of low value care has not been investigated. Notwithstanding, question prompt lists of this kind are typically regarded as a strategy for facilitating shared decision-making5 and thus, improved shared decision-making is an obvious potential mediator of the hypothesised effect of the 5 Questions resource on the use of care.

Despite its potential, focus testing by Choosing Wisely Australia suggested that the 5 Questions Resource alone may not be sufficient for enabling patient question-asking as people may continue to feel that they do not have permission to ask questions.4 In response to this, Choosing Wisely Australia has developed accompanying resources (eg, posters featuring local hospital staff,4 a video illustrating how to have conversations with health professionals)6 that address some potential barriers to the impact of the 5 Questions Resource (eg, the social unacceptability of active participation, patient concerns about healthcare providers’ reactions and possible retribution). However, other elements proposed as critical for preparing patients in advance of exposure to a shared decision-making intervention (eg, explaining that there are two experts in the encounter (healthcare provider and patient), challenging attitudes that there are universally right and wrong decisions)7 8 remain unaddressed by these resources. An intervention that addresses all elements considered critical for patient preparation may enhance the impact of the 5 Questions resource and may also, on its own, be beneficial.7 8

The impact of the 5 Questions resource may also depend on patients’ health literacy9 that is, ‘the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health’.10 Adults with lower health literacy have worse health outcomes (eg, increased hospital admissions and readmissions11 poorer chronic disease outcomes12 and increased mortality13), and importantly ask fewer questions when seeing healthcare providers.14 Previous research shows that interventions that are tailored to an individuals’ health literacy level can support more effective communication and potentially reduce health inequalities for people with lower health literacy.15–17 However, intervention developers often fail to tailor the design of their interventions to adults with lower health literacy and rarely evaluate their impact in this group.

Objectives

Our overall objective of this study is to better understand the potential of the Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions Resource and a newly developed shared decision-making preparation video for facilitating shared decision-making and reducing the use of unnecessary tests, medications and procedures. As this study represents the world’s first evaluation of both interventions, we intend to deliver them online to a community sample using hypothetical vignettes. Participants are asked to imagine being in a specific clinical scenario and proximal cognitive-affective outcomes are assessed following randomisation to different interventions. We consider demonstrating evidence of impact in cognitive and affective outcomes an important first step before embarking on evaluation in the healthcare setting. Our primary aim is to assess the impact of the interventions on participants’ (a) self-efficacy to ask questions and participate in shared decision-making, (b) intention to participate in shared decision-making and (c) a range of secondary outcomes. Our secondary aim is to determine whether health literacy modifies the impact of the interventions.

Methods

The study methods have been informed by an unpublished pilot study of the intervention (n=164), which included a qualitative interview study with a subset of health consumers (n=25) to refine the interventions and outcome measures. Data collection is planned to start in November 2019 and finish in December 2019.

Study design and setting

We will use 2×2×2 between-subjects factorial design (preparation video: yes, no × Choosing Wisely 5 Questions Resource: yes, no × health literacy: adequate, inadequate). This design will enable us to assess the relative impact of different interventions, both alone and in combination compared with no intervention. This design will also allow us to explore whether health literacy modifies the impact of these interventions.

This study will be conducted online using the Qualtrics survey platform. Randomisation will be undertaken via an automated function in the survey platform using an equal allocation ratio and stratification by participant health literacy (adequate, inadequate), yielding four trial arms in each health literacy subgroup: (a) preparation video alone, (b) 5 Questions Resource alone, (c) preparation video and 5 Questions Resource and (d) no intervention. Participants will not be blinded to their assigned intervention.

Participants, recruitment and consent

To be eligible to take part, potential participants must be aged 18 years or older; be an Australian citizen or permanent resident and possess sufficient self-assessed English language skills to complete questionnaires in English.

Participants will be identified, pre-screened for eligibility and invited to consider participation by Dynata, a market research company with a database of 600 000 people willing to be involved in online research. Dynata uses a points system whereby points are earned for completion of surveys which can be redeemed for items such as gift vouchers, donations to charities or cash. If participants agree and are interested in being part of the study, they will be directed to an online survey hosted in Qualtrics. The first page of the survey will display the downloadable Participant Information Statement (see online supplementary appendix B). In line with the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, 2007 (updated 2018), we have received ethical approval to regard completion of the questionnaire as an indication of consent. Participants are also required to select ‘Yes, I would like to participate’ to enter the survey.

bmjopen-2019-033126supp002.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

During the study, all participants will be presented with a hypothetical healthcare scenario that asks them to imagine being in a situation where they have non-specific low back pain and stable pain/symptoms (see box 2). Non-specific low back pain describes pain between the inferior border of the twelfth rib and lower gluteal folds that is not caused by a serious or specific underlying pathology.18 Back pain was the eighth most frequently managed problem Australian general practice in 201519 and non-specific low back pain accounts for approximately 90% of low back pain cases.20 Routine imaging for non-specific low back pain has been shown to have more harms than benefits, and furthermore many medical treatments provide little-to-no benefit over placebo.21 22

Box 2. Hypothetical back pain scenario.

‘You have had lower back pain for about one month; it has not improved or become worse. You did not have an accident to cause the pain; it just began and has not gone away.

You go to your doctor to get advice on what is causing it and what can help with the pain.

The doctor recommends that you have a scan to help figure out what is causing the pain, and gives you a prescription for some medicine’.

Interventions

Preparation video

We developed a short video (3 min) intended to prepare patients for question-asking and shared decision-making. Our rationale for this choice of intervention included that multimedia formats can be a successful tool in engaging and educating patients with low health literacy and encouraging or modifying patient behaviour23–25 and that videos featuring real people have been found to be more effective than those which only provide graphically presented information with voice overs.23 The video script (online supplementary appendix C) was developed through an iterative process and was intended to integrate the recommendations for effective preparation as outlined by Joseph-Williams and colleagues.8 The transcript was developed with reference to the Listenability Style Guide which outlines principles to make spoken discourse more comprehensible and ease the cognitive burden of listening (eg, repetition of ideas; simple and common idioms; vivid analogies; use of questions to focus the listener’s attention).26 The readability level of the script was also checked and adjusted until a grade five readability level was achieved.

bmjopen-2019-033126supp003.pdf (140.8KB, pdf)

Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions Resource

The Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions Resource is a one-page document co-branded by Choosing Wisely Australia and NPS Medicinewise that lists the Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions (see box 1) and provides additional guidance in their rationale and use (see online supplementary appendix A). This resource has a readability score of 9.4.

Implementation of interventions

The interventions will be displayed to participants within the survey platform. To ensure intervention exposure, a timer has been added to the pages displaying the video (3 min) and 5 Questions Resource (1 min), preventing participants from progressing to the next survey page until the specified time has elapsed. In the preparation video and 5 Questions Resource arm, the video will be presented before the 5 Questions resource. Participants will not be prevented from exposure to any other care or interventions prior to or during the study.

Data collection

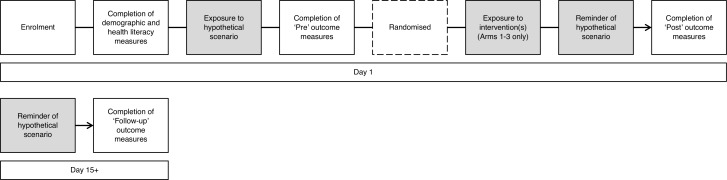

Study data will be collected via surveys administered immediately before (‘Pre’), immediately after (‘Post’) and 2 weeks after (‘Follow-up’) exposure to the relevant intervention(s) (see figure 1). All outcomes will be assessed by participant self-report with the exception of ‘Indicator of proactive intervention use’ (see Outcomes and Measures).

Figure 1.

Time schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments.

Outcomes and measures

Primary and secondary outcomes for the study, as well as measurement instruments and analysis metrics, are shown in table 1. Outcomes and measures were refined following a pilot study (n=164). Unpublished pilot data are available from the authors on request.

Table 1.

Outcomes and measurement

| Outcome | Measure | Pre | Post | Follow-up | |

| Primary | Self-efficacy to ask questions | Single item adapted from Bandura’s self-efficacy theory.36 Participants are asked to rate their degree of confidence to ask questions of their healthcare provider by recording a number from 0 (cannot do at all) to 100 (highly certain can do). | x | x | x |

| Self-efficacy to be involved in healthcare decision-making | Single item adapted from Bandura’s self-efficacy theory.36 Participants are asked to rate their degree of confidence to be involved in decisions with their healthcare provider by recording a number from 0 (cannot do at all) to 100 (highly certain can do). | x | x | x | |

| Self-efficacy to ask questions and be involved in healthcare decision-making | Composite measure based on two individual items (see above). | x | x | x | |

| Intention to engage in shared decision-making | Validated, three-item scale (Cronbach alpha=0.8;31) measuring participants’ (a) likelihood of engaging in shared decision-making, from very unlikely (−3) to very likely (+3), (b) odds of engaging in shared decision-making, from very weak (−3) to very strong (+3) and (c) agreement with the statement ‘I intend to engage in shared decision-making', from total disagreement (−3) to total agreement (+3). Total scores will be rescaled on a scale of 0–6 and the sum of the items divided by three to derive the total score of intention. | x | x | x | |

| Secondary | Intention to follow the treatment plan recommended by the doctor without further questioning | A single item on a 10-point scale, adapted from previous research,37 assessing hypothetical intention to follow the treatment plan recommended by the doctor without further questioning: ‘Which best describes your intention to follow the treatment plan recommended by the doctor without asking further questions?’ (1 = ‘Definitely will not’ to 10 = ‘Definitely will’). | x | x | x |

| Knowledge of patients’ rights in regards to shared decision-making | Four questions adapted from Halaway et al38 and applied to the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights (second edition).39 Participants were asked to indicate ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Unsure’ to show whether they think the following are patient rights: (a) ask questions and be involved in open and honest communication; (b) make choices with your healthcare provider; (c) include the people that you want in planning and decision-making; (d) get clear information about your condition, including the possible benefits and risks of different tests and treatments. A foil question will be included to detect if participants are arbitrarily selecting ‘yes’ to all questions. Scores are dichotomised into (a) all questions correct, or (b) not all questions correct. | x | x | ||

| Attitude toward shared decision-making | Three-item scale adapted from Dormandy et al,40 assessing participants’ perceptions of shared decision-making as beneficial/not beneficial, worthwhile/not worthwhile and important/unimportant. Each item has seven response options, forming a scale from 3 to 21. Scores will be recoded such that higher scores indicate more positive attitudes towards shared decision-making. Participants responding with the highest possible score on all three questions will be classified as having positive attitudes. | x | |||

| Preparedness for shared decision-making (Arms 1-3 only) | Modified, eight-item version of the PrepDM.41 The PrepDM scale was developed to assess a participants’ perception of how useful a decision support intervention is in preparing them to communicate with their practitioner at a consultation visit and to make a health decision. Items are scored on a Likert scale 1–5, from ‘Not at all’ (1) to ‘A great deal’ (5), with higher scores indicating higher perceived level of preparation for decision-making. Items will be summed and the total score divided by 8.41 | x | |||

| Acceptability (Arms 1–3 only) | Adapted from Shepherd et al,42 participants are asked to rate if they would (a) recommend the (intervention) to others and (b) use the (intervention) again on a four-point scale from 1 (Definitely not) to 4 (Yes, definitely).42 Recommendations are dichotomised into would recommend (3 and 4) and would not recommend (1 and 2). | x | |||

| Indicator of proactive intervention use (Arms 1–3 only) | We will assess the proportion of participants who click on a link to their intervention. | x | x | ||

| Healthcare questions | Participants will be asked to write down five questions that they would ask the doctor given the hypothetical healthcare scenario. The content of individual responses will be analysed via content analysis using inductive and deductive approaches (see below). The mean number of questions that map onto the Choosing Wisely 5 Questions will be calculated. | x | x |

PrepDM, Preparation for Decision Making Scale.

Demographic and health data collection

In addition to the primary and secondary outcomes, participants will be asked to report their age, gender, Australian state of residence, language spoken at home, education status, employment status, private health insurance status and confidence in filling out medical forms.27 Participants will also be asked to indicate who is usually involved in healthcare decision-making related to their health, and about their experience and perceived knowledge of low back pain. Health literacy will be assessed by the Newest Vital Sign (NVS),28 with participants categorised as inadequate (score 0–3 on NVS) or adequate literacy (score 4–6 on NVS). The NVS has been used in other online studies,29 and is an objective, performance-based measure of health literacy skills. We will also administer a single-item measure of self-reported health literacy for the purposes of describing the sample.

Analysis

Quantitative data analysis

The study statistician will be blinded to the intervention allocation of participants and their level of health literacy until after completion of analyses; a research assistant who has no other involvement in the trial will remove all group identifiers prior to analysis. Quantitative primary and secondary outcome data will be analysed as intention-to-treat using appropriate regression models (ie, linear regression for continuous outcomes, logistic regression for dichotomous categorical outcomes). Dichotomous variables representing the study factors (preparation video: provided, not provided; Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions resource: provided, not provided; health literacy: adequate, inadequate) and their interactions will be included in models as between-subjects fixed effects, controlling for pre-intervention values (where available). Outcome data collected during the immediate post- and follow-up survey will be analysed in separate models. Any significant interactions will be followed-up by subgroup analyses based on potentially relevant demographic variables.

Missing data

The use of an online survey platform minimises the risk of missing data; participants are required to provide responses to each question before moving on to subsequent items. As such, data are only missing in cases where participants discontinue prior to providing responses for outcome measures. Participants who discontinue the study before completion of the (immediate) post-intervention survey will be excluded from all analyses. Multiple imputation will be used30 to impute occasional cases of missing data (eg, some outcome measures incomplete) or for missing responses for participants who complete the initial (pre- and post-) surveys, but do not return to complete the 2-week follow-up survey. If multiple imputation of missing data is utilised, sensitivity analyses will be performed comparing the outcome from complete case with imputed analyses.

Sample size

Sample size estimates were derived based on the primary outcome of intention score, with the estimates of effect based on previously published values31 and refined considering pilot data. For each stratified analysis arm (ie, inadequate health literacy, adequate health literacy), a sample of n=162 subjects per intervention group is expected to provide approximately 80% power to detect a small main effect (effect size of 0.10 or greater) of the Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions resource; and over 80% power to detect small main effects (effect sizes 0.20 or larger) of the preparation video intervention, and their interaction, at a p-value of 0.05 in primary analyses. As such, we aim to recruit a total sample size of n=1432 (ie, 716 with inadequate health literacy and 716 with adequate health literacy; with n=179 participants randomly allocated to each intervention group [preparation video alone, Choosing Wisely Australia 5 Questions resource alone, both Choosing Wisely questions and preparation intervention, and control]). This will allow for a drop-out of approximately 10% of participants who discontinue the study before completing the (immediate) post-intervention survey measures.

Qualitative data analysis

Assessment of healthcare questions deemed by participants as important to ask in their hypothetical scenario will be analysed via content analysis.32 Coding will first be done deductively based on concepts embodied in the Choosing Wisely Australia 5 questions.33 Two double-blind coders will review all data and code any questions that fit broadly into 1 of 5 categories: Do I really need this test, treatment or procedure? What are the risks? Are there simpler, safer options? What happens if I don’t do anything? What are the costs?34 35 Any discrepancies will be resolved through discussion between coders. Remaining responses will be coded inductively with categories derived from the data.34 Inductive codes will be collected to form coding sheets and categories freely generated and grouped through the abstraction process.34 The coding scheme will be revised over an iterative process of discussion and revision to ensure all themes are captured. Based on our previous work, data will be presented in the form of frequencies expressed as percentages and actual numbers of key categories. We will also report category names, definitions and data examples.

Data storage and management

After enrolment, a unique identifier will be assigned to each study participant. Any participant identifiers will be removed before the data are archived for storage. Data will be downloaded as spreadsheets and stored on password protected computers which are encrypted per university policy. Listed investigators will have access to the final study data set.

Patient involvement

A consumer was involved in the study design. The consumer helped select outcomes and outcome measures, develop and refine the intervention, and will inform the interpretation of the analysis and dissemination of findings. Our study protocol was also presented to a Choosing Wisely Australia Board Meeting, with specific feedback sought from the two consumer board members.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @ErinCvejic, @M_C_Tracy, @zadro_josh

Contributors: Authorship decisions adhered to International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommendations. DM, KM and JKS conceived the original idea for this trial, and this was further developed by EH-fC, RET, EC, MT, JZ and RL. DM and JKS wrote the first draft of this protocol manuscript, and this was edited by all other authors. EC provided valuable input regarding trial design and analytical considerations, and performed the sample size calculations for the trial. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; help@nhmrc.gov.au) Program Grant (APP1113532). NPS MedicineWise gave permission for investigators’ use of the Question Prompt List leaflet without charge. EC was supported by a Sydney Medical School Summer Research Scholarship and KM was supported by an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship (1121110). Neither the NHMRC nor Sydney Medical School had any role in the design of this study. They will not have a future role in the conduct or write-up of the study or in the decision to submit the findings for publication. A representative of Choosing Wisely Australia (RL) contributed to the design of this study and will have a future role in the conduct and write-up of the study. NPS MedicineWise will not have a role in the decision to submit the study findings for publication.

Competing interests: RL is an employee of NPS MedicineWise which facilitates Choosing Wisely Australia. The University of Sydney owns intellectual property on the video and DM, MT, KM and RET are contributors to the intellectual property.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA 2012;307:1513–6. 10.1001/jama.2012.362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levinson W, Kallewaard M, Bhatia RS, et al. 'Choosing wisely': a growing international campaign. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:167–74. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ansley D. 5 questions you need to ask your doctor. consumer reports, 2016. Available: https://www.consumerreports.org/doctors/questions-to-ask-your-doctor/ [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 4. Choosing wisely Australia 2017 report: join the conversation, 2017. Available: http://www.choosingwisely.org.au/getmedia/042fedfe-6bdd-4a76-ae20-682f051eb791/Choosing-Wisely-in-Australia-2017-Report.aspx [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 5. Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision-making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choosing Wisely Australia Starting a choosing wisely conversation, 2019. Available: http://www.choosingwisely.org.au/resources/consumers/conversation-starter-kit [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 7. Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G. Power imbalance prevents shared decision making. BMJ 2014;348 10.1136/bmj.g3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:291–309. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jessup RL, Buchbinder R. What if I cannot choose wisely? Addressing suboptimal health literacy in our patients to reduce over-diagnosis and overtreatment. Intern Med J 2018;48:1154–7. 10.1111/imj.14025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot 1986;1:113–27. 10.1093/heapro/1.1.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mitchell S, Sadikova E, Jack B, et al. And 30-day postdischarge Hospital utilization. J Health Commun 2012;17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schillinger D, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 2002;288:475–82. 10.1001/jama.288.4.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:97–107. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, et al. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns 2004;52:315–23. 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Durand M-A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e94670 10.1371/journal.pone.0094670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muscat DM, Shepherd HL, Morony S, et al. Can adults with low literacy understand shared decision making questions? A qualitative investigation. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1796–802. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muscat DM, Morony S, Shepherd HL, et al. Development and field testing of a consumer shared decision-making training program for adults with low literacy. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1180–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brunner F, Weiser S, Schmid A, et al. Non-specific low back pain : Boos N, Aebi M, Spinal disorders: fundamentals of diagnosis and treatment. Heidelberg, Berlin: Springer Berlin, 2008: 585–601. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2014-2015. Sydney, Australia: University of Sydney, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, et al. Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:3072–80. 10.1002/art.24853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Öberg B, et al. Low back pain: a call for action. The Lancet 2018;391:2384–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30488-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. The Lancet 2018;391:2368–83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abu Abed M, Himmel W, Vormfelde S, et al. Video-Assisted patient education to modify behavior: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2014;97:16–22. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hart TL, Blacker S, Panjwani A, et al. Development of multimedia informational tools for breast cancer patients with low levels of health literacy. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:370–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lopez‐Olivo MA, Ingleshwar A, Volk RJ, et al. Development and pilot testing of multimedia patient education tools for patients with knee osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:213–20. 10.1002/acr.23271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rubin DL, Guide LS. In: Worthington dl, Bodie Gd, EDS. The Sourcebook of listening research: methodology and measures. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc 2017:361–71. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large Va outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:561–6. 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiss BD, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. The Annals of Family Medicine 2005;3:514–22. 10.1370/afm.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ayre J, Bonner C, Cvejic E, et al. Randomized trial of planning tools to reduce unhealthy snacking: implications for health literacy. PLoS One 2019;14:e0209863 10.1371/journal.pone.0209863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Couët N, Labrecque M, Robitaille H, et al. The impact of DECISION+2 on patient intention to engage in shared decision making: secondary analysis of a multicentre clustered randomized trial. Health Expect 2015;18:2629–37. 10.1111/hex.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Choosing Wisely Australia Choosing wisely Australia. An initiative of NPS medicine wise, 2016. Available: www.choosingwisely.org.au [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 34. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N, et al. Qualitative research in health care. analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales : Pajares F, Urdan TC, Self-Efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, Conn: Information Age Pub, Inc, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fisher A, Bonner C, Biankin AV, et al. Factors influencing intention to undergo whole genome screening in future healthcare: a single-blind parallel-group randomised trial. Prev Med 2012;55:514–20. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Halawany HS, AlTowiher OS, AlManea JT, et al. Awareness, availability and perception of implementation of patients’ rights in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Dent Res 2016;7:132–7. 10.1016/j.sjdr.2016.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Australian Commission on safety and quality in healthcare. Australian charter of healthcare rights (second edition), 2019. Available: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/australian-charter-healthcare-rights-second-edition-a4-accessible [Accessed 12 Sep 2019].

- 40. Dormandy E, Michie S, Hooper R, et al. Informed choice in antenatal Down syndrome screening: a cluster-randomised trial of combined versus separate visit testing. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:56–64. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Graham ID, O’Connor AM. Preparation for decision making scale. University of Ottowa, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shepherd HL, Barratt A, Jones A, et al. Can consumers learn to ask three questions to improve shared decision making? A feasibility study of the ASK (AskShareKnow) Patient-Clinician Communication Model ® intervention in a primary health-care setting. Health Expect 2016;19:1160–8. 10.1111/hex.12409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033126supp001.pdf (64.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033126supp002.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033126supp003.pdf (140.8KB, pdf)