Abstract

Objective

Although China has made remarkable progress in strengthening its primary healthcare system, lack of well-performed primary health workforce is still the bottleneck of deepening the reform. The objective of this review is to understand the current profile of Chinese primary care workers (PCWs) and their motivating factors of performance and propose targeted policy suggestions on improving their work performance.

Design

Systematic review.

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed and MEDLINE was conducted to identify articles published from January 1, 2000, to June 2, 2018. Quality assessment and data extraction for the studies closely relevant to performance of PCWs in China were conducted by two reviewers independently. A preliminary framework containing different levels of factors influencing PCWs’ motivation based on existence, growth and relatedness (ERG) theory guided the synthesis analysis. In addition, we used a random-effects model to pool individual studies on job satisfaction and estimate the overall job satisfaction of PCWs.

Results

A total of 36 articles were included; 16 (23 882 participants) in the meta-analysis. Regarding the individual level of motivation, 3 overarching themes and 12 subthemes were developed. The subthemes of financial incentives, career advancement and work itself were frequently mentioned and have more influences on PCWs’ performance. Moreover, the healthcare system reform policies have inevitable and complex impacts on different levels of human needs, and then influences on the motivation and performance of PCWs. Meta-analysis showed that the overall job satisfaction score among PCWs was 3.30, just reaching a satisfied rating and varied in different regions.

Conclusions

This study suggests low work satisfaction among PCWs in China, with financial incentives and career advancement being two most important motivating factors. Efforts to improve the work performance in PCWs should give priority to these motivating factors and systematically take into account the health policy’s impacts on performance of PCWs.

Keywords: primary healthcare, primary care worker, performance, motivation, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A myriad of potentially eligible articles were screened and included using a comprehensive search strategy.

Reliability of the study selection, data extraction and quality assessment was ensured by involving two independent reviewers.

This review contributes to the current literature as it included studies that adopted qualitative, quantitative or mix methods to present a comprehensive overview of the motivating factors on performance of China’s primary care workers.

This study benefited from summarising all the motivating factors on performance of China’s primary care workers in a systematical way, namely, at both an individual level and a health system level.

Chinese articles were not included in this review.

Introduction

In China, the primary healthcare (PHC) services that include public health services and basic medical health services are provided by community health centres (CHCs) and their affiliated community health stations (CHSs) in the urban areas and by township health centres (THCs) and their affiliated village clinics (VCs) in the rural areas. These four types of PHC institutions constitute the essential part of China’s three-tertiary healthcare delivery network. Administered by CHCs and THCs respectively, CHSs and VCs function as the satellite sites of their superior institutions. As is central to China’s health system reform initiated in 2009,1 the strengthening of the primary healthcare has been hindered by the grave challenges concerning the structure of China’s healthcare delivery system, in particular, the low-performance of PHC delivery system.2 From 2010 to 2016, China’s primary care workers (PCWs) have experienced a rise in their number from 3.3 million to 3.7 million, but a decrease in their proportion in health workers, from 40.0% to 33.0%. This trend is mirrored by the utilisation of health services during the same period of time: PHC institutions’ proportion has dropped from 61.9% (3.6 billion visits) to 55.1% (4.4 billion visits) in terms of the outpatient visits and from 27.9% (39.5 million hospitalisations) to 18.3% (41.7 million hospitalisations) in terms of the inpatient visits.3 Against this backdrop, the strengthening of primary health system will remain as the focus of health system reform in the near future, which can be seen from the fact that the Outline of Healthy China 2030 Plan, the government’s blueprint for health system development, has underscored the importance of primary health care.4

Health workforce shortage is one of the major obstacles to strengthen China’s primary healthcare services.5 To make matters worse, the primary health workforce is confronted with serious challenges such as low education level, lack of qualifications, ageing, high turnover and poor working performance.6 Of all the determinants of PCWs’ performance, work motivation, defined as an individual's degree of willingness to exert and maintain an effort towards organisational goals,7 plays a crucial role in changing the behaviour of health providers. It has been demonstrated that work motivation can influence job satisfaction, hence influencing job performance.8 9 There has been an expanding body of studies exploring the motivating factors for PCWs through qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods, but the study sites and methodological quality of these studies varied. Synthesising these motivating factors in different areas of China could help identify the most important motivating factors and appreciate the overall job satisfaction level of PCWs in China. In addition, synthesising the motivating factors for PCWs and analysing the complexity pathway between motivating factors and performance hold general and applicable implications for improving the motivation and performance of China’s PCWs. In light of this, this review aims to synthesise and analyse the motivating factors for PCWs and provide evidence-based policy implication on how to improve the performance of China’s PCWs.

Methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We searched the PubMed and MEDLINE on June 2, 2018, to identify relevant studies using Medical Subject Headings terms in conjunction with free-text words including all the possible synonyms, alternative terms and spellings6 to increase sensitivity to any potentially eligible literature. All the search terms were provided in the online supplementary appendix 1. Search results were exported to EndNote X7 to be organised and duplicate records were removed in the first place. Then two authors exported the citations to Microsoft Excel and conducted the literature screening and selection independently. Divergent judgements were settled through discussion. We searched for and included articles about the motivating factors on performance of the PCWs who work in four types of China’s PHC institutions: rural THCs, rural VCs, urban CHCs and urban CHSs. In this study, motivation in the work context is defined as an individual’s degree of willingness to exert and maintain an effort towards organisational or system goals,10 and the degree of job satisfaction, work stress and turnover intention seen as possible reflections of motivation which may influence work performance. Therefore, all the studies that explored the level of work motivation, job satisfaction, work stress, turnover intention and the influencing factors of these motivation expressions were included. We also searched for relevant studies found in the references of the included articles and other sources. The included studies adopted either observational or experimental design, and presented primary quantitative or qualitative data. All the included articles were in English language and published between 2000 and 2018. Studies were excluded if they did not address the motivating factors for PCWs, or if the participants were not PCWs or did not work in the four types of PHC institutions mentioned above.

bmjopen-2018-028619supp001.pdf (335.4KB, pdf)

Assessment of risk of bias

Methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using Hoy’s risk of bias tool which is adapted from the one developed by Leboeuf-Yde and Lauritsen.11 Based on a total score, studies are put into three categories: low risk of bias (8 to 10), moderate risk of bias (5 to 7) and high risk of bias (0 to 4).

Data extraction and synthesis

Extracted data included study design, year or years of study, settings, participants, sample sizes, measurement of motivation, objective, key motivation conclusions and motivating factors. Data extraction and analysis were guided by Alderfer's existence, growth and relatedness (ERG) theory, which proposes three core human needs in organisational settings: existence (the desire for material things), relatedness (the desire for cordial interpersonal relations) and growth (the desire for opportunities to be creative and to develop one’s skills).12 A thematic synthesis approach was adopted for data analysis to capture the evidence illustrating PCWs’ motivation. Motivating factors extracted from the included articles were grouped into four themes: (1) factors concerning the existence needs, including payment, fringe benefits and physical working conditions; (2) factors concerning the relatedness needs, which are concerned with social environment and relationship; (3) factors concerning the growth needs, referring to career or self-development and management environment; (4) factors concerning the health policy context and organisational context that could influence one or more needs categories mentioned above (online supplementary appendix 2). The first three themes of motivating factors represented, at an individual level, three different dimensions of human needs in PHC institutions based on the existence, growth and relatedness (ERG) framework and the last theme was singled out because different health policies had complex impacts on the performance by influencing more than one dimension of human needs at a macro level. First, authors aggregated data into motivating factors and extracted all original motivating factors in each article to put them into one of the four themes. Then we identified correlations between the different factors, refined them through discussion and synthesised similar factors into a higher level theme.

As job satisfaction was positively associated with job performance13 and nearly half of the selected articles studied job satisfaction with quantitative measurement, we resorted to meta-analysis to synthesise the 16 articles that provide data of PCWs’ job satisfactions. We unified the measurement of overall job satisfaction by transforming different calculations into a 5-point rating scale and pooled the study-specific estimates using a random effects meta-analysis model to obtain an overall summary of the job satisfaction scores across studies.14 We analysed the data using Stata V.14.0 for Windows.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in this study.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design; data collection, analysis and interpretation; writing of the report and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

Characteristics of reviewed studies

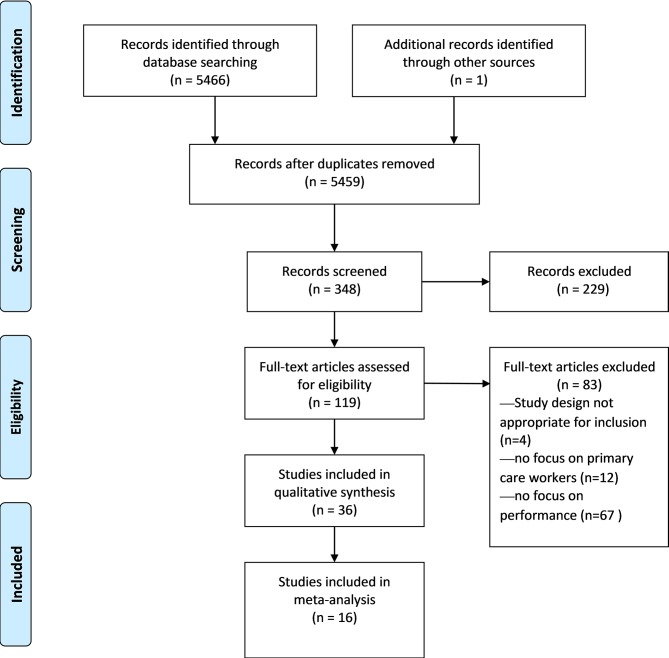

We first screened 5466 titles and abstracts, and then retrieved and screened the full-texts of 348 potential relevant studies to evaluate their eligibility (figure 1). After the full text screening, 119 studies relevant to the human resources of PHC in China were included for us to appreciate the current status of PCWs. To obtain sufficient information related to the motivation of PCWs, one additional article from reference search was also identified and included after applying the eligibility criteria. Finally, of the 119 studies, 83 articles that did not contain specific motivating factors were excluded; 36 articles that were closely relevant to PCWs’ motivation for were selected for data extraction and synthesis. A list of the basic characteristics of the included articles can be found in online supplementary appendix 3. Twenty-five quantitative, seven qualitative and four mixed methods primary studies were included, covering at least 27 provinces of China. All of the 36 articles were cross-sectional studies, with 17 studies taking place in rural China, 11 in urban China and 8 in both China’s urban and rural areas. Of the 17 studies concerning rural areas, 8 articles only included village doctors in village clinics as participants, 5 articles only studied health workers in THCs and 4 articles were concerned with rural PCWs in both village clinics and THCs. The 11 studies that were concerned with urban areas addressed urban PCWs in community health centres/stations. Eight articles studied all types of PCWs in different kinds of rural and urban PHC institutions. As for the risk of bias, more than half of the included studies presented a low risk of bias, with the total score ranging from 6 points to 10 points (in online supplementary appendix 3). Included studies analysed the motivation of PCWs from different perspectives: some measured job satisfaction15–30; some explored the motivating factors’ influence on attrition and retention18 22 31–35; some studied the impact of some policies or interventions on the motivating factors for health workers.31 36–46

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram.

Motivating factors for PCWs

Factors concerning existence needs

Financial incentives, workload and the work conditions related to a person's physical needs such as food, clothing and shelter were clustered into factors concerning existence needs. In this review, we found that work conditions, payment and the mandatory workload were considered as significant factors of PCWs’ satisfaction15 19 20 22 23 25 30 47 and turnover intention.18 22 Twenty-six out of the 36 articles reported financial incentives (table 1) and found that the financial incentives such as income and fringe benefits were significantly associated with job satisfaction15 17 30 and difficulties in PCW recruitment.32 34 35 Moreover, financial incentives and working conditions were the top two motivating factors for PCWs to improve performance.21 33

Table 1.

Motivating factors for primary care workers

| Motivating factor | Definition | Motivation to stay | Motivation to join/leave | Number of selected studies reporting the factors |

| Existence | ||||

| Financial incentives | Basic salary, bonus, benefits (insurances, vacation, etc.) | 22 | 5 | 26 |

| Workload | Hours of work, the amount of work done, flexibility in scheduling | 12 | 1 | 13 |

| Work conditions | Work environment, job stability, job security | 14 | 2 | 15 |

| Relatedness | ||||

| Living environment | Geographical location and socioeconomic level of workplace | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Recognition in society | Patients’ respect, workplace violence, social status | 11 | 2 | 13 |

| Work itself | Nature of work (interest, meaningfulness, enjoyment), job fullfilment, job achievement, work enthusiasm | 17 | 1 | 17 |

| Working relationships | Relationships with coworkers/subordinates/nurses, communication | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Growth | ||||

| Career advancement | Opportunities for professional development | 17 | 3 | 19 |

| Training | Support for training and education, opportunity to learn new skills and new knowledge | 11 | 2 | 13 |

| Rewards | Recognition, appreciation, contingent rewards, | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Management | Supervision (level of competence, fairness, interest in subordinates), relationship with superior | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Autonomy | Opportunities to do work by making decisions on their own. opportunity to utilise your professional skills and talents | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| System and policy | ||||

| The healthcare reform policies | Putting organisational policies into practice eg, NEMS, NBPHSP and TVHSIM |

18 | 1 | 18 |

Another line of inquiry explored the impact of different health system reform policies on motivating factors. For example, in a qualitative study, administrators and front line healthcare workers in PHC institutions mentioned that the increased income after the 2009 health system reforms did not fully reflect the increased workload, and those who worked the most were not necessarily rewarded the most, constituting a demotivating factor for some health workers.37

Factors concerning relatedness needs

Relatedness needs refer to a person's interpersonal needs in his personal and professional settings and in this review, factors concerning relatedness needs were deemed as person’s relationships with the living environment, the society, the coworkers and the nature of work.

Seventeen studies reported work itself and 11 studies reported work relationships (table 1). Compared with factors concerning existence needs, the PCWs were more satisfied with the nature of work and work relationships.20 25 30 This finding indicated that most workers got along well with their colleagues and believed that their jobs were to be of value, which can act as a motivating factor in case of poor physical environment.

Thirteen of the selected studies reported recognition from society including being understood by society and physician-patient relationships (table 1). Satisfaction with social status and relationship with patients was significantly associated with job satisfaction.15 30 In terms of patients’ respect, there seemed to be an urban-rural difference, with the rural PCWs being slightly more satisfied than their urban counterparts.23 However, few rural PCWs expressed satisfaction with their current relationships and indicated that the patients could not understand the doctor’s work.47 In addition, the growing workplace violence negatively affected the PCWs’ job performance and quality of life48 and emerged as a major contributor to doctors’ low morale in recent years.16

Six studies reported living environment as a factor concerning relatedness needs (table 1) and showed that compared with urban areas, rural areas had greater needs to improve the living environment.21 33 In addition, young health workers’ weakening sense of belonging and responsibility to their hometown has made it more difficult to recruit young health workers born in local areas.32

Factors concerning growth need factors

Career advancement, training, rewards, management and autonomy relating to a person's needs of personal development were considered as factors concerning growth needs in this review.

Nineteen out of the 36 articles reported the factor of career advancement (table 1), which was considered as the one of top three contributors to satisfaction.15 16 19 20 22 23 29 The gap between the expected and actual professional development was one of the main sources of job dissatisfaction.17 Limited opportunities for job promotion was another factor contributing to the low levels of work passion19 and turnover intentions of village doctors.18 22 The main causes might be that few positions and opportunities were available for the health professionals in PHC institutions to get higher professional titles on the regular payroll, especially compared with the opportunities that their counterparts in higher level health institutions can enjoy.

Training was mentioned as a motivating factor by 13 out of the 36 articles (table 1). Learning and training were significantly associated with work passion,19 job satisfaction15 29 and turnover intention.22 Along with career advancement, training was also considered as one of the most important motivating factors for PCWs to improve performance.21 However, training arrangements were inadequate34 49 50 to address the fragmented needs of China’s PCWs. Health workers preferred more training time for practice-focused training (on-site guidance from senior doctors and further clinical education) over knowledge-focused training, and favoured such training contents as clinical skills, preventive healthcare and medication knowledge education.49 As a result, although training was reported as an effective incentive in recruitment, it failed to act as an effective motivating factor to attract young doctors to rural areas in China.34

Among the selected studies, the number of studies that reported the motivating factors of rewards, management and autonomy stood at 9, 9 and 14, respectively (table 1). According to most of the selected articles, PCWs were relatively satisfied with the decision-making ability of their superiors, the contingent rewards and the opportunities to do work by making decisions on their own and to utilise their professional skills and talents.15 22

System and policy factors

Motivation was not only influenced by the motivating factors at the individual level, but also by the health sector reforms and specific incentive schemes that target workers.7 Theoretically, any health sector reform would directly influence the motivating factors that the health workers feel or that affect the structure of health organisations, thus in turn affecting the work rewards of the health workers. Eighteen out of the 36 articles reported macro-level factors (table 1), namely, the health system and policy factors such as National Essential Medicines System (NEMS), National Basic Public Health Service Program (NBPHSP) and Township and Village Health Services Integration Management (TVHSIM) (online supplementary appendix 4). The gap between the intended and actual consequences of the policies was one of the main determinants of job satisfaction.17 The comprehensive reform of PHC in Anhui has changed PCWs’ compensation structure and improved their income and work efficiency, but dampened their work enthusiasm because of the poorly designed performance-based evaluation system.37 Different economic status and health reform processes may lead to different consequences. Take the comprehensive reform of PHC in Shandong as an example, PCWs there on the one hand complained about increased trivialities at work, heavier workload, blurry job description, unsatisfactory income and a lack of professional development, but on the other hand were satisfied with the relationships with the community and low work pressure.41

The NEMS included a new National Essential Drugs List to ensure free access to safe and effective medication for the patients, and introduced a series of polices on drug production, pricing and distribution in the hope of promoting the rational use of medications by reducing the reliance on drug sales and profit seeking behaviours. To be more specific, only drugs on the list were allowed to be prescribed in VCs and price mark-ups were forbidden. The impacts of the NEMS varied by region, professional practice and income level.42 In one survey, most PCWs perceived no change in their income and reported a high level of satisfaction towards NEMS.45 However, according to another in-depth interview with village doctors,36 the introduction of the essential drug list for PHC institution dramatically reduced their medical income as most areas had limited government subsidies to supplement their incomes. At the same time, they also complained that they had lost patients’ trust and work enthusiasm as the classes and total amount of essential medicines were not enough to meet daily treatment needs.42 45

The NBPHSP starting from 2009 provided a package of basic public health services for all residents, with a focus on the management of non-communicable disease. To motivate PCWs to provide preventive health services, the government grants subsidies based on the number of covered residents. At the beginning of this reform, due to the broad scope of basic public health services and limited financial incentives, providers felt that they were under great stress due to the competing demands for their time and complained about the heavy workload, insufficient remuneration, staff shortage, lack of formal professional identity and ineffective performance appraisal. In addition, providers had to deal with the distrust and disrespect from some residents,40 46 especially those public health workers who were dismissed as having lower levels of knowledge and skill than specialists.39 Providers with more subsidies, training opportunities and integrated management had better performance in service provision.44

The TVHSIM required THCs, the upper-level health institutions, to direct and supervise VCs in their routine work and their work in medicine, personnel management, financing and the upgrade and maintenance of facilities, resulting in mixed impacts on village doctors. On the one hand, most village doctors felt more respected under this integrated management because they were more recognised as health workers in a formal health system rather than private drug salesmen. On the other hand, they were not allowed to perform agricultural or any other side activity for extra money,26 36 which negatively affected their financial conditions.

Job satisfaction for PCWs

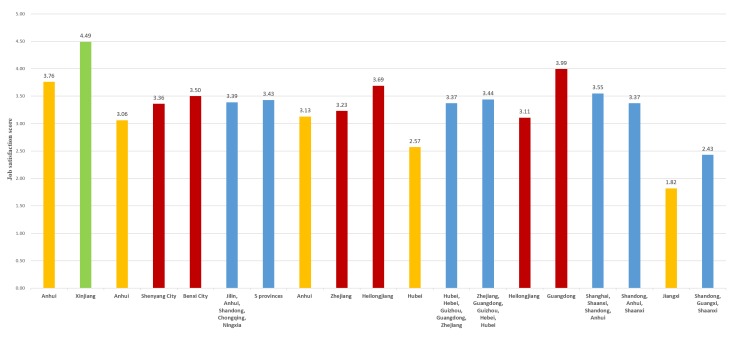

The performance of healthcare delivery system is critically dependent on workers’ motivation which is directly mediated by workers’ willingness.7 As an important indicator to measure workers’ willingness to exert efforts, satisfaction is highly relevant for the sustainable development of PHC in China. Sixteen included articles assessed job satisfaction as an important dimension reflecting providers’ motivation (see online supplementary appendix 5). A total of 19 investigation samples were extracted from these 16 articles with cross-sectional study design, representing more than half of the provinces in China. In particular, two articles24 25 provided data of two provinces/cities and one article20 represented data of 2 years. The overall job satisfaction score ranged from 1.82 to 4.49 and also varied from region to region (figure 2). To be more specific, for most samples drawn from more than three provinces, the satisfaction scores levelled off between 3.37 and 3.55, but the samples from the middle area samples scored lower than those from the eastern area. Besides, the score of Xinjiang, the representative of the western areas, was the highest among the included samples.

Figure 2.

Job satisfaction score among primary care workers across different regions in China.

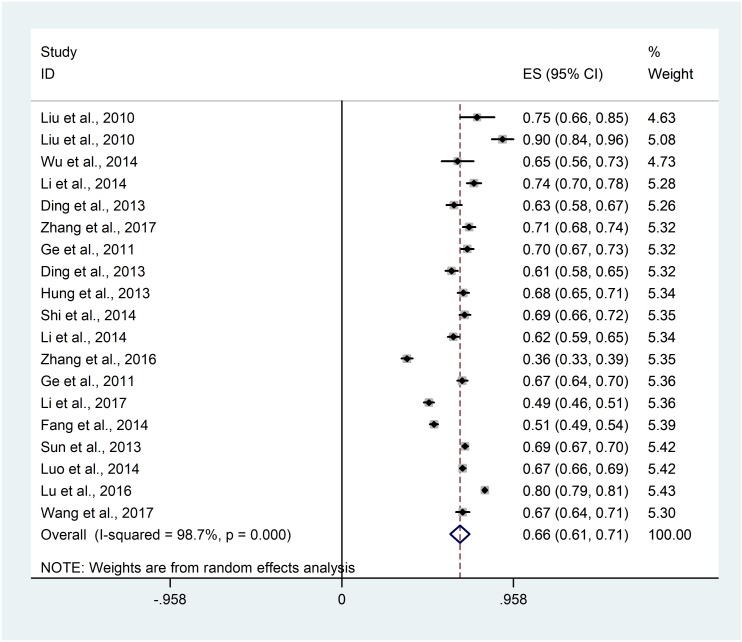

Meta-analysis was approached by combining results weighted by sample size and showed that the overall job satisfaction score among PCWs was 3.30, equivalent 0.66 ((95% CI 0.61 to 0.71); I²=98.7%; p<0.001; figure 3), just reaching a level indicating satisfaction. But the overall satisfaction mean of rural health workers was lower than that of the urban health workers (table 2).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the job satisfaction score among primary care workers

Table 2.

Means of overall job satisfaction score among primary care workers

| Study | No. of included studies | Mean |

| All included studies | 19 | 3.30 |

| Studies in urban areas | 9 | 3.35 |

| Studies in rural areas | 7 | 3.06 |

NBPHSP, National Basic Public Health Service Program; NEMS, National Essential Medicines System; TVHSIM, Township and Village Health Services Integration Management.

Discussion

Financial incentives and career advancement were the top two motivating factors for PCWs in China

In the included articles, the balance between remuneration and workload was most frequently mentioned as a critical motivating factor on PCW’s performance. In spite of Chinese government’s considerable investments in recent years to improve the income of the health workers in PHC institutions, the gap between the actual and expected income continued to widen due to increasing urbanisation and ever growing living costs. According to some doctors in THCs, the performance-based salary means that 30% to 40% of the salary was based on their workload, quality of service and patients' satisfaction, but due to the limit of overall revenue and revenue structure, the well-performing health workers can only be rewarded by reducing the income of their co-workers with poor performance. This payment method did not work well in reality as to motivate health workers. How to improve the income level of health workers in primary health delivery system will remain a crucial but tricky issue in the near future. Besides, as shown in our analysis in figure 2, financial incentives were no longer the sole means to promote motivation, improve job satisfaction and enhance work performance. Other factors, in particular, professional development, work characteristics and training, have been equally, if not more, important for China’s PCWs. More specifically, the lack of chances for professional title promotion and limited career development opportunities were important reasons that lead to turnover intention. This finding is in line with other internationally published studies and underscores the importance of the non-financial as well as the financial incentives.7 51 The ERG framework implies that the fulfilment of human needs plays an important role in PCWs’ motivation, but each individual prioritises the existence needs, relatedness needs and growth needs differently. In this review, we found that the PCWs in China are confronted with barriers in fulfilling all of the three levels of human needs. Income security has increased, but still far lower than the expected level; the residents’ recognition of and cooperation with the PCWs have played a negative role in influencing the motivation and behaviours of health workers; career promotion system and training arrangements did not meet their growths need neither. Policymakers must realise that a health worker has multiple needs to be met simultaneously. In addition, motivation improvement should be prioritised in a way that suits local institutional environments and personal preference. A sole focus on one type of need at a time cannot effectively motivate PCWs.52

The overall job satisfaction score among PCWs was still low, especially in rural areas

As the predictor of job satisfaction, the overall job satisfaction score reflects PCWs’ emotional status and to what extent their human needs are satisfied. PCWs’ performance can be considerably improved by identifying the motivating factors so as to increase their work satisfaction. The most prominent factor causing the general dissatisfaction of PCWs, especially the PCWs in rural areas, was the financial rewards from work. In 2014, the annual income of 84.06% village doctors was less than 30 000 RMB, much lower than the average income (56 394 RMB) of the doctors in Jiangxi province’s higher level health institutions, and nearly half of the village doctors thought that they earned less than other people in the local area.15 In addition, as discussed above, the health system reform policies also had indirect and negative impacts on PCWs’ income level and further reduced their job satisfactions. These findings hold significant implications for policymakers and PHC institution managers who make efforts to improve workers’ job satisfaction.17 28 Another finding of the synthesis was the significant differences of satisfaction scores among eastern, western and middle regions of China. There is no doubt that imbalance exist among these regions at all levels. As for the satisfactions of PCWs, provinces in the eastern region, with more developed economy and better health facilities, scored higher than provinces in the middle region and lower than provinces in the western region. Considering western China are remote areas with less economic development, the higher job satisfaction of PCWs may be explained by the lower expectations of PCWs, more government subsidies and other central government supports that target remote western areas. In light of this, the government should take into account the imbalanced development of China’s different areas, especially China’s middle area where the economic development and resources are limited and the central government’s subsidies are also absent.

The health system reform and some specific policies have inevitable and indirect impacts on PCWs

In 2009, China launched a landmark healthcare reform which aims at providing affordable and equitable basic healthcare for all by 2020.5 As strengthening the primary health system is central to the health system reform, several policies have directly targeted PHC institutions or PCWs. As a result, the satisfaction of pay and contingent rewards have improved slightly, which may be attributed to the fact that PCWs’ basic wages are guaranteed by government finance.20 However, despite of the progress China has made in enhancing the primary health system, new problems and unintended consequences of related reform have surfaced. For example, the brain drain of experienced health workers and the loss of patients from THCs to county hospitals have incurred a great cost.6 31 As for the health system reforms, three policies and their respective impacts on health workers’ motivation were most studied in the literature.

Since its introduction in 2009,36 the NEMS has exerted a lasting impact on PCWs’ income structure. The essential drug list removed the incentives for over-prescribing, resulting in a drop in income and a loss of autonomy31 because government subsidies for public health workers were not enough to compensate the decline in PHC institutions’ revenue from drug prescriptions. Along with the problems in drug supply procurement, unintended consequences on health workers’ motivation and related behaviours also emerged: THCs has suffered a brain drain of experienced health workers who have flowed to county hospitals because their prescriptions have been restricted due to a limited supply of medicines and they have lost many patients as a result. In conclusion, policymakers should consider how to reduce the policy’s adverse effects on the motivation of PCWs, including how to appropriately remunerate health workers, ensure enough clinical autonomy and supply the drugs in a timely, transparent and accountable manner.

At the beginning of the NBPHSP, the PCWs responsible for basic public health services held negative attitudes toward the sustainable provision of these services because it was accompanied by a heavier workload and insufficient subsidy to compensate their efforts.38 40 44 46 To motivate PCWs, the government has increased the subsidies from 15 RMB per person in 2009 to 50 RMB in 2017. However, the combination of heavy workload, rigid performance assessment procedure and lack of professional knowledge remained unchanged, resulting in a negative effect on PCWs’ job satisfaction and performance. We suggest that the evaluation of PCWs’ performance be shifted from being fault-finding oriented to being support-providing oriented, such as improving the ability of public health providers or strengthening the teamwork between clinical doctors and the public health workers in order to enhance the overall delivery of these public health services.

After the implementation of TVHSIM, the village doctors who had been previously self-employed and not integrated into the formal health delivery system, were managed in the same way as THC staffs and experienced a transformation of their income structure as government subsidy has become an increasing source of income. They were motivated not only by the more stable financial subsidy from government, but also by the good reputation and respect from local residents as health providers with formal status. However, their income and fringe benefits still lagged behind the regular employees in THCs, which remained an demotivating factor for village doctors.34 A well-rounded social insurance model for village doctors is urgently needed.43

The rationale for using ERG theory to guide the analysis lies in the fact that this needs-based theory generally encompasses work motivation, provides a useful conceptualisation of what PCWs care about (motivating factors) and explains their performance in organisations. The findings of this review suggest that PCWs can be encouraged to perform well by positive motivations responding to satisfying ERG needs, but it should be interpreted with caution because of several limitations. First, this review only focuses on the motivating factors of PCWs’ work performance, therefore, other relevant articles on motivating factors influencing the attraction of PCWs were excluded by the search strategy. Second, all the included studies analysed PCWs’ motivation from the perspective of problems and critics, which could lead to some bias because few positive thoughts on PCW’s current motivation status have been reported. Third, factors related to personal sociodemographic characteristics and mental state were not analysed as motivating factors. They were only exacted from the original article and presented as influencing factors, as shown in the online supplementary appendix 3.

Conclusions

Low motivation is at the crux of promoting the work performance of China’s on-service PCWs. Policymakers should take into account all level of human needs that influence PCWs’ motivation and start from the local reality to set priorities to ensure of PCWs’ appropriate remuneration and career development opportunities. Just as illustrated by the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health, efforts should be made to improve deployment strategies, working conditions, reward systems, continuous professional development opportunities and career pathways by adopting and implementing evidence-based health workforce policies that are tailored to the local context so as to make the best possible use of limited resources and enhance both capacity and motivation for improved performance.52 We also suggest that countries undergoing health system reform should consider the views of different stakeholders and analyse the potential side effects of some specific policies on health providers who are not directly targeted in order to benefit both providers and demanders.15

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Xi Li from National Clinical Research Center of Cardiovascular Diseases, State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, for their support and technical advice on the inclusion criteria.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors proposed the hypothesis and idea for the systematic review and take responsibility for all aspects of it. QM, BY and HL discussed and contributed to the conceptualisation of this review and the development of review protocol. BY applied the inclusion criteria. HL and DW extracted the data. HL was a major contributor to the draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This review was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71403008) and Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available from the authors.

References

- 1. State Council of the People’s Republic of China Guanyu shenhua yiyao weisheng tizhi gaige de yijian (opinions on deepening health system reform) 2009. (in Chinese).

- 2. Huang J, Shi L, Chen Y. Staff retention after the privatization of township-village health centers: a case study from the Haimen city of East China. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:136 10.1186/1472-6963-13-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China 2016 China health and family planning statistical yearbook (in Chinese). Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Publishing House, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. CPC Central Committee, State Council The plan for “Healthy China 2030” (in Chinese), 2016. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm

- 5. Yip WC-M, Hsiao WC, Chen W, et al. Early appraisal of China's huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet 2012;379:833–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li X, Lu J, Hu S, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet 2017;390:2584–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:1255–66. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dolea C, Adams O. Motivation of health care workers-review of theories and empirical evidence. Cahiers de sociologie et de demographie medicales 2005;45:135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fisher CD. Why do lay people believe that satisfaction and performance are correlated? possible sources of a commonsense theory. J Organ Behav 2003;24:753–77. 10.1002/job.219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bennett S, Franco L. Health worker motivation and health sector reform. Bethesda, Maryland: Abt Associates, Partnerships for Health Reform, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guterman SS, Alderfer CP. Existence, relatedness, and growth: human needs in organizational settings. Contemp Sociol 1974;3:511 10.2307/2063565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, et al. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol Bull 2001;127:376–407. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang M, Yang R, Wang W, et al. Job satisfaction of urban community health workers after the 2009 healthcare reform in China: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:14–21. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X, Fang P. Job satisfaction of village doctors during the new healthcare reforms in China. Aust Health Rev 2016;40:225–33. 10.1071/AH15205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu D, Wang Y, Lam KF, et al. Health system reforms, violence against doctors and job satisfaction in the medical profession: a cross-sectional survey in Zhejiang Province, eastern China. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006431 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li L, Zhang Z, Sun Z, et al. Relationships between actual and desired workplace characteristics and job satisfaction for community health workers in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:180 10.1186/s12875-014-0180-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fang P, Liu X, Huang L, et al. Factors that influence the turnover intention of Chinese village doctors based on the investigation results of Xiangyang City in Hubei Province. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:84 10.1186/s12939-014-0084-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luo Z, Bai X, Min R, et al. Factors influencing the work passion of Chinese community health service workers: an investigation in five provinces. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:77 10.1186/1471-2296-15-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ding H, Sun X, Chang W-wei, et al. A comparison of job satisfaction of community health workers before and after local comprehensive medical care reform: a typical field investigation in central China. PLoS One 2013;8:e73438 10.1371/journal.pone.0073438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hung L-M, Shi L, Wang H, et al. Chinese primary care providers and motivating factors on performance. Fam Pract 2013;30:576–86. 10.1093/fampra/cmt026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun Y, Luo Z, Fang P. Factors influencing the turnover intention of Chinese community health service workers based on the investigation results of five provinces. J Community Health 2013;38:1058–66. 10.1007/s10900-013-9714-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shi L, Song K, Rane S, et al. Factors associated with job satisfaction by Chinese primary care providers. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2014;15:46–57. 10.1017/S1463423612000692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ge C, Fu J, Chang Y, et al. Factors associated with job satisfaction among Chinese community health workers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:884 10.1186/1471-2458-11-884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu JA, Wang Q, Lu ZX. Job satisfaction and its modeling among township health center employees: a quantitative study in poor rural China. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:115 10.1186/1472-6963-10-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li T, Lei T, Sun F, et al. Determinants of village doctors' job satisfaction under China's health sector reform: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:64 10.1186/s12939-017-0560-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li L, Hu H, Zhou H, et al. Work stress, work motivation and their effects on job satisfaction in community health workers: a cross-sectional survey in China 2014;4:e004897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang M, Yan F, Wang W, et al. Is the effect of person-organisation fit on turnover intention mediated by job satisfaction? A survey of community health workers in China. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013872 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang H, Tang C, Zhao S, et al. Job satisfaction among health-care staff in township health centers in rural China: results from a latent class analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1101 10.3390/ijerph14101101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu Y, Hu X-M, Huang X-L, et al. Job satisfaction and associated factors among healthcare staff: a cross-sectional study in Guangdong Province, China. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011388 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou XD, Li L, Hesketh T. Health system reform in rural China: voices of healthworkers and service-users. Soc Sci Med 2014;117:134–41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen M, Lu J, Hao C, et al. Developing challenges in the urbanisation of village doctors in economically developed regions: a survey of 844 village doctors in Changzhou, China. Aust J Rural Health 2015;7 10.1111/ajr.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meng Q, Yuan J, Jing L, et al. Mobility of primary health care workers in China. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:24 10.1186/1478-4491-7-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang J, Su J, Zuo H, et al. What interventions do rural doctors think will increase recruitment in rural areas: a survey of 2778 health workers in Beijing. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:40 10.1186/1478-4491-11-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Song K, Scott A, Sivey P, et al. Improving Chinese primary care providers' recruitment and retention: a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:68–77. 10.1093/heapol/czt098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang S, Zhang W, Zhou H, et al. How China's new health reform influences village doctors' income structure: evidence from a qualitative study in six counties in China. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:26 10.1186/s12960-015-0019-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu Q, Tian X, Tian J, et al. Evaluation of the effects of comprehensive reform on primary healthcare institutions in Anhui Province. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:268 10.1186/1472-6963-14-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ding Y, Smith HJ, Fei Y, et al. Factors influencing the provision of public health services by village doctors in Hubei and Jiangxi provinces, China. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:64–9. 10.2471/BLT.12.109447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao Y, Cui S, Yang J, et al. Basic public health services delivered in an urban community: a qualitative study. Public Health 2011;125:37–45. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhou H, Zhang W, Zhang S, et al. Health providers' perspectives on delivering public health services under the contract service policy in rural China: evidence from Xinjian County. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:75 10.1186/s12913-015-0739-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang M, Wang W, Millar R, et al. Coping and compromise: a qualitative study of how primary health care providers respond to health reform in China. Hum Resour Health 2017;15:50 10.1186/s12960-017-0226-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang T, Liu C, Ren J, et al. Perceived impacts of the National essential medicines system: a cross-sectional survey of health workers in urban community health services in China. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014621 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Feng D, Zhang L, Xiang Y-X, et al. Satisfaction of village doctors with the township and village health services integration policy in the Western minority-inhabited areas of China. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2017;37:11–19. 10.1007/s11596-017-1687-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li T, Lei T, Xie Z, et al. Determinants of basic public health services provision by village doctors in China: using non-communicable diseases management as an example. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;16:42 10.1186/s12913-016-1276-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Song Y, Bian Y, Li L. Current perspectives on China’s national essential medicine system: primary care provider and patient views. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;16:30 10.1186/s12913-016-1283-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li X, Cochran C, Lu J, et al. Understanding the shortage of village doctors in China and solutions under the policy of basic public health service equalization: evidence from Changzhou. Int J Health Plann Manage 2015;30:E42–55. 10.1002/hpm.2258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen Q, Yang L, Feng Q, et al. Job satisfaction analysis in rural China: a qualitative study of doctors in a township Hospital. Scientifica 2017;2017:1–6. 10.1155/2017/1964087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin W-Q, Wu J, Yuan L-X, et al. Workplace violence and job performance among community healthcare workers in China: the mediator role of quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:14872–86. 10.3390/ijerph121114872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li X, Liu J, Huang J, et al. An analysis of the current educational status and future training needs of China's rural doctors in 2011. Postgrad Med J 2013;89:202–8. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mo Y, Hu G, Yi Y, et al. Unmet needs in health training among nurses in rural Chinese township health centers: a cross-sectional hospital-based study. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2017;14:22 10.3352/jeehp.2017.14.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Henderson LN, Tulloch J. Incentives for retaining and motivating health workers in Pacific and Asian countries. Hum Resour Health 2008;6:18 10.1186/1478-4491-6-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. World Health Organization Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030, 2016. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/global_strategyHRH.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028619supp001.pdf (335.4KB, pdf)