Abstract

Objective

As the discipline of nursing has advanced, research capacity in nursing has become increasingly important to the discipline’s development. However, research capacity in nursing is still commonly used as a buzzword, without a consistent and clear definition. The purpose of this study is to clarify the concept of research capacity in nursing by identifying its conceptual components in the relevant nursing literature using the Pragmatic Utility method.

Design

A Pragmatic Utility concept analysis based on a scoping review.

Data sources

Academic literature retrieved from PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT).

Eligibility criteria

Qualitative studies, quantitative studies, mixed method studies or literature reviews focusing on research capacity in nursing published in English between 2009 and 2019.

Results

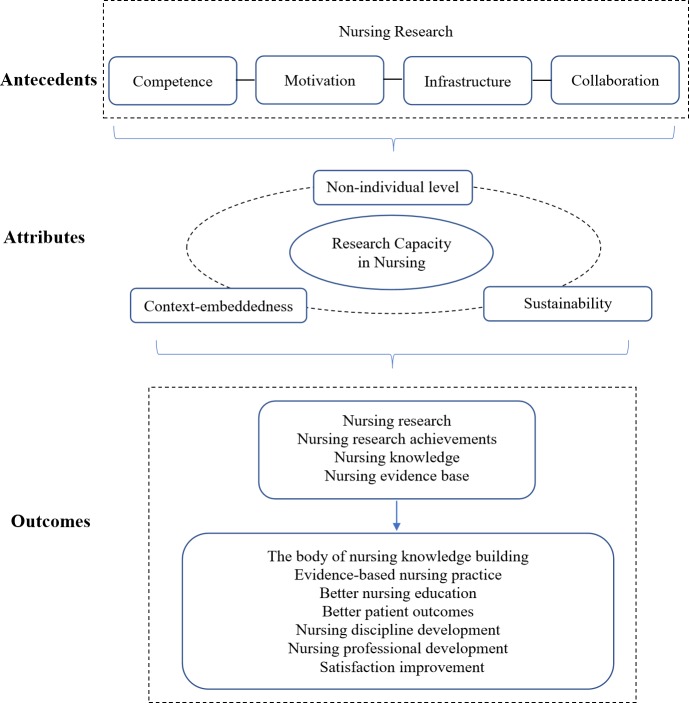

Competence, motivation, infrastructure and collaboration for nursing research are the antecedents of research capacity in nursing. The attributes of research capacity in nursing are ‘non-individual level’, ‘context-embeddedness’ and ‘sustainability’. The direct outcome of research capacity in nursing is nursing research. The allied concepts identified are nursing research competency, nursing research capability and evidence-based practice capacity in nursing.

Conclusions

Research capacity in nursing is the ability to conduct nursing research activities in a sustainable manner in a specific context, and it is normally used at a non-individual level. Research capacity in nursing is critical for the development of the nursing discipline, and for positive nurse, patient and healthcare system outcomes. More studies are needed to further explore the allied concepts of research capacity in nursing, and to better understand relationships among these allied concepts.

Keywords: research capacity, nursing, concept analysis, scoping review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of Pragmatic Utility concept analysis method based on relevant literature collected through a scoping review contributed to a rigorous and comprehensive concept analysis.

The data extraction was conducted by two researchers independently and the results were checked by the third researcher.

Literature published before 2009 and outside the six databases were not included in this study.

Only studies published in English were included.

Introduction

Research capacity has received a great deal of international attention in the nursing discipline.1 2 One reason for this attention is that nursing has gradually become an independent scientific discipline which requires its own body of knowledge. Furthermore, with evidence-based practice spreading worldwide, nurses, as healthcare professionals, are responsible for delivering high-quality care based on the best available evidence.3 The bodies of knowledge for nursing as a scientific discipline and for credible evidence for evidence-based nursing practice should be based on high-quality nursing research studies. Such studies can only be conducted if excellent research capacity exists in the nursing discipline.4

In the past three decades, many countries and organisations have made concerted efforts to develop and improve research capacity in the discipline of nursing.5 However, these policy-level supports provided by countries and organisations are insufficient for significantly improving the limited research capacity in nursing6 7; interventions to strengthen research capacity in nursing must be informed by scientific research. Therefore, more studies focusing on how to improve nursing research capacity are needed in order to provide evidence for policymakers, as well as to develop and refine interventions for improving research capacity in nursing.3 5 However, before evidence-based interventions can be developed to improve research capacity in nursing, researchers and policymakers must have a clear and common understanding of what is meant by ‘research capacity in nursing’. Based on our review of the literature, there is not an established understanding of this concept.

A concept analysis of research capacity in nursing can produce a rigorous definition and understanding of the concept, which will allow for more relevant high-quality studies to be conducted.8 In addition to the concept analysis’s potential contributions to future studies on research capacity in nursing, this concept analysis could also help nurses, nurse managers and nurse leaders to better understand research capacity in nursing.8 Nursing is not only a scientific or theoretical discipline; it is also a profession whose practice should be based on evidence. Nurses, as the end-users of the evidence in their practice, are increasingly expected to participate in nursing-related research activities, to bridge the gap between nursing research and nursing practice and to improve the quality of the nursing care they provide to their patients.3 5 In order to facilitate the participation of more nurses in nursing research — and thus to help improve research capacity and evidence-based practice in clinical practice settings — there is an urgent need for nurses, nurse managers and leaders and healthcare policymakers to first have a better understanding of research capacity in nursing.

A concept analysis involves analysing the literature relevant to the concept, to form a better understanding of the concept’s meaning and the contexts in which it is used.8 After a broad search and review of the literature, no clear definition or specific conceptual dimensions (antecedents, attributes and outcomes) of research capacity in nursing were found (in fact, no clear definition and concept analyses of research capacity in any health-related discipline were found).9 Based on Morse’s process and criteria for concept maturity evaluation,10 research capacity in nursing is recognised as a partially mature concept. Partially mature concepts are those concepts having multiple or problematic definitions, ambiguous meanings and confusion with use. These concepts are often used inconsistently in practice and research.11 For partially mature concepts, the Pragmatic Utility concept analysis method is considered to be appropriate for developing the concept further.8 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to further develop the concept of research capacity in nursing by conducting a Pragmatic Utility concept analysis based on relevant literature.

Method

Pragmatic Utility is a meta-synthesis technique used to synthesise literature and advance the development of partially mature concepts by using the literature as the data source.8 The strengths of the Pragmatic Utility method include its use of extensive data sources, its well-articulated criteria and procedures for concept evaluation and concept analysis, and its inclusion of intellectual processes of critical appraisal for asking analytical questions (ie, the questions that researchers spontaneously ask themselves as they are reading the literature, to reveal the information needed for concept analysis) and synthesising the results.12 These traits of the Pragmatic Utility method may help it to overcome some of the limitations (eg, insufficient data sources, the use of dictionary definitions and invented cases and less emphasis on a clear definition of the concept and its boundaries with other concepts) of other concept analysis methods, such as Wilsonian-derived methods and Rodgers’ evolutionary method.8 12

In Pragmatic Utility, researchers examine and appraise the definition, antecedents, attributes, outcomes and use of a partially mature concept in the literature by asking analytical questions and answering those questions.8 Analytical questions play an important role in Pragmatic Utility. The identification of analytical questions occurs through the researchers’ interpretative readings, deep understanding and critical appraisal of the literature. For instance, these are the spontaneous questions that researchers have as they are reading, where they recognise aspects of the concept which they do not quite understand, or aspects which the researchers recognise have inconsistencies across the literature analysed thus far. Such questions can guide researchers towards extracting ever more relevant data from the literature, and sorting these data further according to the responses the researchers developed for the analytical questions they first asked.11

The antecedents, attributes, boundaries and outcomes of the concept can be identified and a definition can be developed through the methodical process of asking and answering analytical questions. Additionally, allied concepts may be found during the concept analysis process.8 Antecedents are the conditions that always precede and give rise to the concept. Attributes are the key characteristics of the concept.8 Boundaries, which are normally formed by the antecedents and attributes of a concept, are the invisible lines between the concept and other concepts; they delineate what the concept is and what it is not.13 Outcomes are the results or consequences of the concept. Allied concepts are those concepts that ‘closely resemble one another, and may even share some attributes, but are different and separate concepts in their own right’.8 Allied concepts can help to further clarify the boundaries of concepts and provide implications for further studies (eg, a concept comparison of allied concepts).

The data source for a Pragmatic Utility concept analysis is the literature related to the concept. Ideally, a larger sample of the relevant literature may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the concept. However, the Pragmatic Utility concept analysis method does not provide a detailed description of the procedures for retrieving relevant literature.8 The scoping review method is ‘an ideal tool to determine the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a given topic and give clear indication of the volume of literature and studies available as well as an overview (broad or detailed) of its focus’.14 The scoping review method offers a rigorous and replicable literature search process for collecting rich sources of secondary data.14 Considering the systematic literature search method used by scoping reviews can provide a large sample of papers for conducting a concept analysis, we used the literature search method of scoping review to retrieve all relevant literature for our study.15 A scoping review of the nursing literature on research capacity in nursing can also help to explore all the contexts in which the concept is used.

The researchers in our research group were three graduate students experienced in conducting nursing research and literature reviews, as well as three professors in nursing. The following steps were followed to conduct a Pragmatic Utility concept analysis based on a scoping review8 11 16: (1) ‘Clarify the study purpose’, (2) ‘Search literature broadly and select appropriate literature’, (3) ‘Get inside the literature’, (4) ‘Read the literature interpretively and identify analytical questions’, (5) ‘Record responses on a data collection sheet’, (6) ‘Synthesise the results’.

Clarify the study purpose. The clarification of this study’s purpose was the first step of the concept analysis and the premise of the literature search. The purpose of this study was to conduct a concept analysis for research capacity in nursing.

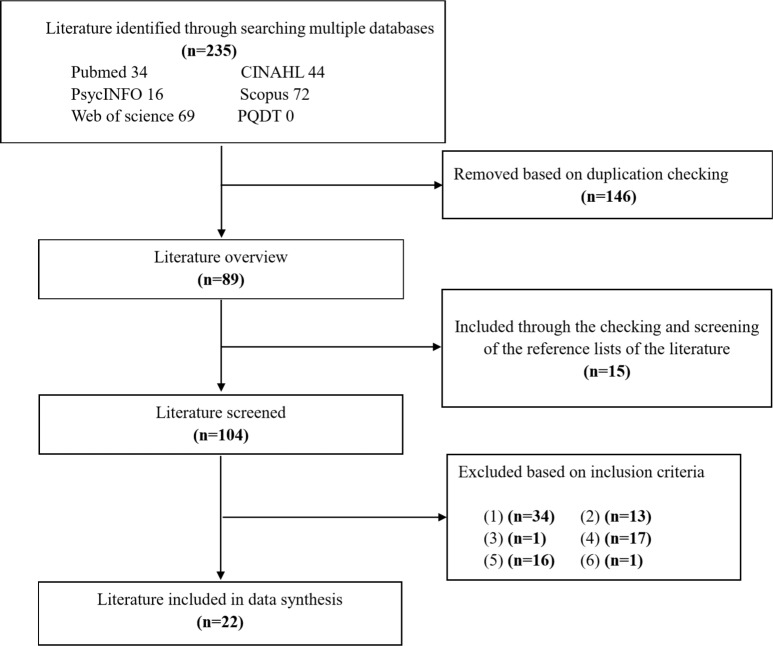

Search literature broadly and select appropriate literature. Based on the purpose of this study, we used ‘research capacity’ AND ‘nursing OR nurse*’ as keywords in the literature search (a search strategy example is shown in figure 1). Databases searched included the PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT). After removing the duplicates, a total of 89 records remained in the EndNote library, which was the literature management software used in this study. The additional 15 papers, which were identified as relevant literature through the checking and screening of the reference lists of the 89 articles, were then imported into the EndNote library, as well. Appropriate articles for the concept analysis were then screened for based on the following inclusion criteria for the literature selection: (1) published between 2009 and 2019 (to explore the most current use of the concept), (2) access to the full-text, (3) published in English, (4) the topic is research capacity in nursing, (5) the articles were qualitative studies, quantitative studies, mixed method studies or literature reviews and (6) not from the same research programme as another study already included in the analysis. Two researchers were responsible for screening the literature selection. Finally, 22 articles were included as the data source for the concept analysis. The flowchart of the literature selection process for the concept analysis is shown in figure 1.

Get inside the literature. Two researchers read the selected literature in detail to extract explicit information showing the antecedents, attributes, outcomes, definition and allied concepts of the concept and to get a preliminary understanding of the included literature.8 The tracking system table developed by Weaver was used as a tool for documenting details gathered through the readings relating to the concept’s definition, antecedents, attributes, outcomes and allied concepts.11 The data extraction was conducted by two researchers independently using the tracking system table, and the final results were checked and combined by the third researcher. The tracking system table provided a method to manage the copious data and to help make the research process transparent. We extracted a small part of this tracking system table as an example, shown in the online supplementary appendix 1. The complete tracking system table can be acquired from the corresponding author on request.

Read the literature interpretatively and identify analytical questions. After the previous step of ‘get inside the literature’, three researchers further read the literature interpretatively to extract implicit information showing the anatomy of the concept (these data were sorted and then added into the tracking system table), and simultaneously, to read the literature critically in order to identify analytical questions. Then, we held a meeting to discuss, debate and determine the final analytical questions that required further exploration. The final analytical questions identified are shown in the ‘Analytical questions’ column in table 1.

Record responses on a data collection sheet. Based on the existing data in the tracking system table, two researchers further extracted additional data needed for answering analytical questions from the literature and then responded to the analytical questions based on all the data extracted. A matrix (the first two columns of table 1) on a data collection sheet was used to organise the responses to the analytical questions. For example, the fifth analytical question was ‘What factors are demanded for or could directly influence nursing research capacity?’ All related data in included literature which could answer this question were extracted and used to answer the analytical question, and the answers were recorded as ‘responses from literature’ in the data collection sheet. The answers were summarised and shown in the ‘Responses from literature’ column in table 1.

Synthesise the results. In a research group meeting, researchers used each set of responses in the matrix (the ‘Responses from literature’ column in table 1) to recognise commonalities and differences for summarising implicit and explicit conceptual components of the concept. This step was a process of comparing, contrasting and synthesising the data extracted from the literature. The conceptual components extracted are shown in the ‘Conceptual components’ column in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and selection process. Note 1 - Example: search strategy in PubMed: (research capacity[Title]) AND (nursing[Title/Abstract] OR nurse*[Title/Abstract]). Note 2 - Inclusion criteria of literature selection were: (1) published between 2009 and 2019 (to explore the most current use of the concept), (2) access to the full-text, (3) published in English, (4) the topic is research capacity in nursing, (5) the articles were qualitative studies, quantitative studies, mixed method studies or literature reviews and (6) not from the same research programme as another study already included in the analysis. Note 3 - CINAHL,Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; PQDT, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Table 1.

Analytical questions, responses from literature and conceptual components of research capacity in nursing

| Analytical questions | Responses from literature | Conceptual components |

| Definition | ||

| 1. Is nursing research capacity a kind of competence? | 1. No | |

| 2. Is nursing research capacity a kind of ability? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Is motivation a part of nursing research capacity? | 3. No (except Torres et al) | Ability |

| 4. Does nursing research capacity completely include evidence-based nursing practice capacity? | 4. No, but related | Nursing research activities |

| Antecedents | ||

| 5. What factors are demanded for or could directly influence nursing research capacity? | 5. Nursing research (1) Knowledge, skills, experience (2) Motivation, passion, awareness, incentives, encouragement, interest, attitude, value (3) Infrastructure, time, funding, education, academic support, mentorship, supervision, material supports, resources, research culture, management, policy (4) Collaboration, partnership, linkage, networks, teamwork, community, multidisciplinary, interprofessional |

Nursing research competence motivation infrastructure collaboration |

| Attributes | ||

| 6. On what level(s) is nursing research capacity used on? | 6. Group level, organisational/Institutional level, regional level, national level, international level, discipline level | Non-individual level |

| 7. Is nursing research capacity reinforced internally or externally? | 7. Both (internal, external, contextualise, context, local, settings, suitable, tailored) |

Context-embeddedness |

| 8. Does nursing research capacity focus on present ability or ability over the long-term? | 8. Ability over long-term (long-term, sustainability, sustainable, continuity) |

Sustainability |

| Outcomes | ||

| 9. How is nursing research capacity manifested? | 9. Nursing publications, nursing conference presentations and posters, projects, grants, funding | Nursing research achievements |

| 10. What are the consequences of nursing research capacity? | 10. Nursing research, knowledge building, evidence base development, evidence-based practice, maturity of nursing as a scientific discipline, improvement of the quality of nursing care, high-quality outcomes in nursing academic and clinical arenas, improved attitudes toward nursing research, better patient care, better patient outcomes, enhance quality and patient safety, professional growth, improvement in nurses’ satisfaction, decrease in nursing turnover, cost saving | Nursing research Nursing knowledge, nursing evidence base The body of nursing knowledge building, evidence-based nursing practice Better nursing education, better patient outcomes Nursing discipline development, nursing professional development, satisfaction improvement |

The following articles provided data sources for concept analysis: Akerjordet et al 2012,27 Begley et al 2014,20 Corchon et al 2011,22 Crozier et al 2012,18 Edwards et al 2009,29 Fullam et al 2018,1 Goeppinger et al 2009,21 Gullick and West 2016,25 Hauck et al 2015,35 Jamerson and Vermeersch 2012,31 Kulage and Larson 2018,2 Landeen et al 2017,17 Lee and Metcalf 2009,28 Lode et al 2015,5 Martínez 2012,23 McAllister and Brien 2017,32 McKee et al 2017,7 Moore et al 2012,24 O'Byrne and Smith 2011,3 Renwick et al 2017,33 Torres et al 2017,19 Wilkes et al 2013.26

bmjopen-2019-032356supp001.pdf (42.1KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

No patients or members of the public were involved.

Findings

A total of 22 articles met the inclusion criteria and provided the rich data source for our Pragmatic Utility concept analysis. The antecedents of research capacity in nursing were identified as competence, motivation, infrastructure and collaboration for nursing research. The attributes of research capacity in nursing were identified as ‘non-individual level’, ‘context-embeddedness’ and ‘sustainability’. The direct outcome of the concept of research capacity in nursing was nursing research. The allied concepts identified were nursing research competency, nursing research capability and evidence-based practice capacity in nursing. The findings are shown in table 1. A proposed conceptual framework of research capacity in nursing is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual components of research capacity in nursing.

The contextual use of research capacity in nursing

In the literature, research capacity in nursing was used both in clinical nursing contexts (eg, in the context of hospitals, clinical institutions, clinical nurse settings, etc),1 5 17 18 and academic nursing contexts (eg, higher education, universities, departments of nursing, research institutes, etc).2 19–21

Anatomy of research capacity in nursing

Antecedents

Competence

Individual competence (knowledge, skills and experience) for nursing research is a premise of the ability to conduct nursing research activities.22 Educational programmes, training, mentorship, academic-clinical collaborations, journal clubs, seminars, workshops, academic meetings, experiential learning opportunities and research facilitators were all approaches found in the literature for improving or providing the research competence of individual nurses towards achieving research capacity in nursing.1 7 17 19

Motivation

Motivation — which is the individual and contextual willingness, interest in and desire for nursing research — is a precondition for gaining research capacity.5 7 23 Studies revealed different strategies for enhancing motivation, such as ensuring that the research was relevant to practitioners by asking research questions that emanate from practice, disseminating research evidence and incorporating research into practice to help nurses realise the contributions of nursing research to their practice.3 7 24

Another factor that stimulates motivation centres around building a cultural environment that appreciates the value of nursing research.25–27 Building a culture that values nursing research and is then committed to its development requires commitment at different levels – that is, at the individual, group, organisational/institutional and national/societal levels.3 17 19 28 29 Commitment also requires: a clear understanding of what nursing research is, transparent role expectations and requirements of nurse researchers and the creation of opportunities of career pathways of nurses who are research-active.3 A strong research culture also requires encouragement and support from peers,1 as well as a system that rewards research productivity and outputs.7 24

Infrastructure

Infrastructure was defined as the structures and processes that were set up to enable the smooth and effective running of nursing research activities.30 It includes academic support, material support, management support and research culture. Individual research competence requires opportunities for long-term improvement. Therefore, academic support (eg, supervision, mentorship, expert consultation, educational opportunities and partnership with experienced nursing researchers) is indispensable as a form of infrastructure for nursing research activities.1 3 7 Material support (eg, time, human resources, equipment, information, funding, library resources and software for nursing research) is another necessary part of the infrastructure for nursing research activities.5 19 22 Management support includes adequate organisational structure to enable nursing research capacity, supervision, steering groups, research facilitators and coordinators for the management and organisation of nursing research.7 19 25 27 A research culture (which, as noted above, can promote motivation for nursing research) is another form of infrastructure that supports nursing research activities.5 26 31

Collaboration

Research is the activity of many people who are engaged in a collaborative process in order to generate knowledge. Therefore, collaboration is a precondition for research capacity in nursing. Academic-clinical collaboration, novice-expert collaboration, multisite collaboration, interprofessional collaboration and multidisciplinary collaboration were different forms of collaboration found in the literature on research capacity in nursing.1 3 5 7 18 22 24

Attributes

Non-individual level

Compared with nursing research competence — which mainly refers to the knowledge, skills and experience required for an individual to conduct nursing research activities — research capacity in nursing is a concept that uses a relatively macro perspective.32 In the literature, research capacity in nursing is commonly a term used at the group level (clinical nurses, nursing academics),7 20 organisational/institutional level (unit, hospital, department/school, university),2 18 32 regional level,1 national level, international level24 and discipline level.5 23 An individual nurse’s ability to conduct research is not typically referred to as the nurse’s ‘research capacity’, but rather as the nurse’s ‘research competence’.

Context-embeddedness

Research capacity in nursing is embedded in a specific context. It emphasises the ability to act ‘in a specific context’, rather than the competence (knowledge, skills and experience) possessed by individuals, which generally are less influenced by the context. The context could be a unit, hospital, department/school, university, region, nation or even the international community.7 Many researchers have pointed out that the consideration of contextual factors is crucial for nursing research capacity building.5 17 19 33 There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach for improving nursing research capacity, which is closely related to and influenced by context.7 The importance of the construction of a strong research culture in order to build nursing research capacity also supports the assertion that nursing research capacity is context-embedded.5

Sustainability

As nursing research is a long-lasting and never-ending process requiring continuity and sustainability, research capacity in nursing emphasises the ability to conduct research activities ‘in a sustained manner’.34 Therefore, research capacity in nursing requires a setting that could sustainably support the conduction of research activities and research capacity improvement.17 25 The characteristic of sustainability was embodied in almost all intervention studies on research capacity building.

Boundaries

Boundaries differentiating what is and what is not research capacity in nursing are formed invisibly, based on the antecedents and attributes of the concept.13 Research capacity in nursing would not exist if there were no antecedents of competence, motivation, infrastructure and collaboration for nursing research. The usage of research capacity in nursing also implied certain attributes. Research capacity in nursing was normally used in discussions of nursing at the non-individual level and in a specific context. Finally, references to this concept frequently implied that the research capacity in nursing was sustainable.

Outcomes

The direct outcome of research capacity in nursing is nursing research for research achievements (eg, publications, conference presentations and posters, projects/grants/funding)2 20–22 25 28 35 which build nursing knowledge for the nursing discipline and the evidence base for nursing practice.5 19 24 26 27 35 Furthermore, the body of knowledge building and evidence-based practice can provide better nursing education and patient outcomes,3 5 7 24 27–29 31 33 which lead to nursing discipline development and improved satisfaction for various stakeholders (ie, nurses, patients, organisation and the nation/society).3 5 22 25 27 28 31

Definition

Based on our critical analysis of the concept in the relevant literature, the following definition of research capacity in nursing was developed. Research capacity in nursing is the ability to conduct nursing research activities in a sustainable manner in a specific context, and it is normally used at a non-individual level. It is critical for the development of the nursing discipline, as well as for positive patient, nurse and healthcare system outcomes.

Allied concepts

Several allied concepts of research capacity in nursing were found during the concept analysis: nursing research competency, nursing research capability and evidence-based practice capacity in nursing. Nursing research competency and nursing research capability were both not used consistently with the same meaning in the literature. They were used ambiguously in most articles without a clear definition.18 19 22 24 Evidence-based practice capacity focused more on the ability to ‘use evidence in practice’ in a specific context.36 However, no concept analyses were found for these allied concepts.

Discussion

This study was conducted to clarify the concept of research capacity in nursing by identifying its conceptual components using the Pragmatic Utility method based on a scoping review. During the broad literature search in this study, we identified some studies which focused specifically on research capacity in clinical nursing settings.1 5 17 18 This suggests that nursing research is no longer merely the ‘default’ responsibility for nursing academics in academic nursing settings (eg, departments/schools of nursing, universities, nursing research institutions), but has also become integrated into the role expectations and requirements for clinical nurses. The research engagement of clinical nurses who are the end-users of nursing evidence is imperative in reducing the gap between research and clinical practice in order to promote evidence-based practice, which contributes to positive nurse, patient, organisational and even national/societal outcomes.21 Nursing academics also play a necessary role in clinical nursing research as they are crucial for improving research rigour. Therefore, the collaboration of clinical nurses and nursing academics is important for high-quality nursing studies that are directly relevant to nursing practice. This is also consistent with one antecedent of research capacity in nursing: collaboration.

As antecedents are the conditions that always precede and give rise to the concept, to effectively attain or improve research capacity in nursing, it is necessary to simultaneously provide and promote its antecedents.8 The evidence from intervention studies on nursing research capacity building corroborates this conclusion.1 7 22 24 25 Policymakers and nurse managers should propose and implement policies and strategies which promote competence, motivation, infrastructure and collaboration for nursing research, to provide the necessary conditions for cultivating research capacity in nursing. By promoting these antecedents, policymakers and nurse managers can facilitate the improvement of research capacity in nursing. However, if these antecedents are ignored, they may act as barriers to the improvement of research capacity in nursing. For instance, a lack of appropriate research infrastructure (eg, funding, material support) is a barrier to improving research capacity in nursing.

Research capacity in nursing is commonly used at a non-individual level (one of the attributes we noted), suggesting that it is a concept used more with a macro perspective.32 However, because of the lack of a consistent definition of research capacity in nursing, a few researchers used research capacity in reference to research knowledge, skill and interest/attitude on the individual level.37 38 In those few cases, using the term ‘research competence and attitude’ might have been more suitable, based on the findings of this study which found that generally, research capacity in nursing was used at a non-individual level.

This concept analysis recognised ‘context-embeddedness’ and ‘sustainability’ as the other two attributes of research capacity in nursing. Therefore, in interventions for improving research capacity in nursing, an understanding of the local context as well as a plan for sustainability should be all included. It is suggested that rigorous interventions for improving nursing research capacity will be complex, multilevel and long-term processes.5 7 20 23 These rigorous requirements may point to a reason for the paucity of intervention studies on research capacity building: this kind of intervention is impossible to implement without an excellent research group with adequate funding, the sustained support of various levels of related social/managerial groups and an understanding of the specific context being targeted by the intervention. In this context, smaller, more feasible studies focusing on improving just one or several antecedents of nursing research capacity should also be encouraged to progressively add to the foundational knowledge of research capacity building.

Another important reason for the limitations of intervention studies is a lack of appropriate measurement instruments for research capacity in nursing.3 This concept analysis could provide a foundation for further studies on the development of instruments measuring research capacity in nursing. These instruments could be used to measure nursing research capacity at a certain point of time, to monitor variation tendencies of nursing research capacity which could show the effectiveness of an intervention and to provide evidence to refine the intervention. Furthermore, such instruments could provide a baseline assessment of research capacity. Baseline assessments can help to develop specific and pertinent intervention plans for research capacity improvement, according to the specific baseline condition and needs within a specific context.19

Nursing research competency, nursing research capability and evidence-based practice capacity in nursing were allied concepts identified during this concept analysis. However, there are no consistent definitions or concept analyses of these concepts. Additionally, the differences and relationships between these allied concepts and nursing research capacity are not entirely clear. Further studies (eg, concept analysis, concept comparison) could be considered to explore the nature of these allied concepts, and to identify differences and relationships between these concepts.

Limitations

There are two main limitations of this study. First, our study only included literature written in English. Therefore, language-specific nuances in the concept may be missed, which could have deepened our understanding of this concept. Second, literature published before 2009 and outside the six databases were not included in this study. These restrictions may have led to the omission of some relevant studies that could have revealed the earlier development of the concept. Our rationale for including literature after 2009 in this concept analysis was that we found a study which pointed out that the concept of research capacity had not been well defined before 2009,9 and our purpose was to develop a definition and provide a better understanding of the meaning of the concept for present-day policymaking and research programming rather than to provide the whole development history of the concept.

Conclusions and implications

This concept analysis used the Pragmatic Utility method based on a scoping review to further develop the partially mature concept of research capacity in nursing. Through this concept analysis, we have defined research capacity in nursing as the ability to conduct nursing research activities in a sustainable manner in a specific context, normally at the non-individual level. This in-depth concept analysis contributes to theory development related to research capacity in nursing. The clearer definition and deeper understanding of research capacity in nursing could encourage policymakers, managers, nursing philosophers and researchers to consistently and effectively use the concept in documents, nursing literature and academic and policy communications. The analysis of antecedents and attributes encourages policymakers, nurse managers and researchers to further consider strategies on multiple levels to promote nursing research competence, motivation, infrastructure and collaboration, in order to build research capacity in nursing. This concept analysis also provides a foundation for the development of instruments measuring for research capacity in nursing, which could improve the methodological rigour of studies and promote the comparability, transferability and evidence synthesis of related study results. Such instruments would also positively influence nursing management because they could be used to evaluate the nursing research capacity of specific nursing groups (not of individuals). These developments would contribute further to nursing research capacity building, leading to the progressive development of the nursing discipline and positive patient, nurse and healthcare system outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Dr Laurie Gottlieb who provided support for critical reviews and editing of this paper, as well as to Miss Chuyi Zhou and Dr Dan Liu who provided supports as research group members.

Footnotes

Twitter: @QirongChen1, @AimeeRCastro

Contributors: Author contributions - Study design: QC, ST; Data collection: QC, AC; Data analysis: QC, MS, ST; Study supervision: ST, MS; Manuscript writing: QC, AC; Critical revisions for important intellectual content: ST, MS, AC.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Fullam J, Cusack E, Nugent LE. Research excellence across clinical healthcare: a novel research capacity building programme for nurses and midwives in a large Irish region. Journal of Research in Nursing 2018;23:692–706. 10.1177/1744987118806543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kulage KM, Larson EL. Intramural pilot funding and internal grant reviews increase research capacity at a school of nursing. Nurs Outlook 2018;66:11–17. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Byrne L, Smith S. Models to enhance research capacity and capability in clinical nurses: a narrative review. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:1365–71. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9th ed Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lode K, Sørensen EE, Salmela S, et al. Clinical Nurses’ Research Capacity Building in Practice—A Systematic Review. Open J Nurs 2015;05:664–77. 10.4236/ojn.2015.57070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Segrott J, McIvor M, Green B. Challenges and strategies in developing nursing research capacity: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2006;43:637–51. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKee G, Codd M, Dempsey O, et al. Describing the implementation of an innovative intervention and evaluating its effectiveness in increasing research capacity of advanced clinical nurses: using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Nurs 2017;16:21 10.1186/s12912-017-0214-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morse JM. Analyzing and conceptualizing the theoretical foundations of nursing. Springer Publishing Company, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corchön S. The development, implementation and evaluation of a strategy to enhance nursing research in clinical nursing [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Sheffield, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morse JM, Mitcham C, Hupcey JE, et al. Criteria for concept evaluation. J Adv Nurs 1996;24:385–90. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.18022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weaver K, Morse JM. Pragmatic utility: using analytical questions to explore the concept of ethical sensitivity. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2006;20:191–214. 10.1891/rtnp.20.3.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weaver K, Mitcham C. Nursing concept analysis in North America: state of the art. Nurs Philos 2008;9:180–94. 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2008.00359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weaver K, Morse J, Mitcham C. Ethical sensitivity in professional practice: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:607–18. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hawkins SF, Morse J. The praxis of courage as a foundation for care. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014;46:263–70. 10.1111/jnu.12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landeen J, Kirkpatrick H, Doyle W. The hope research community of practice: building advanced practice nurses' research capacity. Can J Nurs Res 2017;49:127–-36. 10.1177/0844562117716851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crozier K, Moore J, Kite K. Innovations and action research to develop research skills for nursing and midwifery practice: the innovations in nursing and midwifery practice project study. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:1716–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Torres GCS, Estrada MG, Sumile EFR, et al. Assessment of research capacity among nursing faculty in a clinical intensive university in the Philippines. Nurs Forum 2017;52:244–53. 10.1111/nuf.12192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Begley C, McCarron M, Huntley-Moore S, et al. Successful research capacity building in academic nursing and midwifery in Ireland: an exemplar. Nurse Educ Today 2014;34:754–60. 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goeppinger J, Miles MS, Weaver W, et al. Building nursing research capacity to address health disparities: engaging minority baccalaureate and master's students. Nurs Outlook 2009;57:158–65. 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corchon S, Portillo MC, Watson R, et al. Nursing research capacity building in a Spanish Hospital: an intervention study. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:2479–89. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martínez N. Developing nursing capacity for health systems and services research in Cuba, 2008-2011. MEDICC Rev 2012;14:12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moore J, Crozier K, Kite K. An action research approach for developing research and innovation in nursing and midwifery practice: building research capacity in one NHS Foundation trust. Nurse Educ Today 2012;32:39–45. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gullick JG, West SH. Building research capacity and productivity among advanced practice nurses: an evaluation of the community of practice model. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:605–19. 10.1111/jan.12850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilkes L, Cummings J, McKay N. Developing a culture to facilitate research capacity building for clinical nurse consultants in generalist paediatric practice. Nurs Res Pract 2013;2013:1–8. 10.1155/2013/709025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Akerjordet K, Lode K, Severinsson E. Clinical nurses' attitudes towards research, management and organisational resources in a university hospital: Part 1. J Nurs Manag 2012a;20:814–23. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01477.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee G, Metcalf S. Building research capacity: through a hospital-based clinical school of nursing. Nurse Educ Today 2009;29:350–6. 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edwards N, Webber J, Mill J, et al. Building capacity for nurse-led research. Int Nurs Rev 2009;56:88–94. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00683.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooke J. A framework to evaluate research capacity building in health care. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:44 10.1186/1471-2296-6-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jamerson PA, Vermeersch P. The role of the nurse research facilitator in building research capacity in the clinical setting. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration 2012;42:21–7. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31823c180e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McAllister M, Brien DL. 'Pre-Run, Re-Run': an innovative research capacity building exercise. Nurse Educ Pract 2017;27:144–50. 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Renwick L, Irmansyah, Keliat BA, et al. Implementing an innovative intervention to increase research capacity for enhancing early psychosis care in Indonesia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2017;24:671–80. 10.1111/jpm.12417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Condell SL, Begley C. Capacity building: a concept analysis of the term applied to research. Int J Nurs Pract 2007;13:268–75. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2007.00637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hauck YL, Lewis L, Bayes S, et al. Research capacity building in midwifery: case study of an Australian graduate midwifery research intern programme. Women Birth 2015;28:259–63. 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Duffy JR, Culp S, Sand-Jecklin K, et al. Nurses' research capacity, use of evidence, and research productivity in acute care: year 1 findings from a partnership study. J Nurs Adm 2016;46:12–17. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tveit B, Solum EM, Simango M. Building research capacity in Malawian nursing education—A key to development and change. J Nurs Educ Pract 2015;5:1 10.5430/jnep.v5n10p1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ekeroma AJ, Kenealy T, Shulruf B, et al. Building capacity for research and audit: outcomes of a training workshop for Pacific physicians and nurses. J Educ Train Stud 2015;3:179–92. 10.11114/jets.v3i4.774 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032356supp001.pdf (42.1KB, pdf)