Abstract

Objectives

This research project aims at estimating the prevalence of cigarette smoking relapse and determining its predictors among adult former smokers in the USA.

Setting

This research analysed secondary data retrieved from the Tobacco Use Supplement-Current Population Survey 2010–2011 cohort in the USA.

Participants

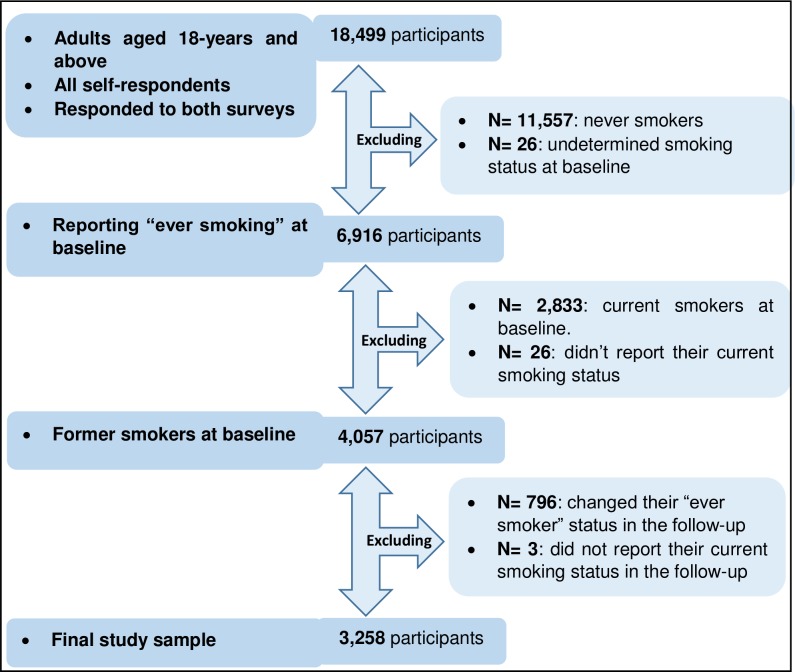

Out of 18 499 participants who responded to the survey in 2010 and 2011, the analysis included a total sample size of 3258 ever smokers, who were living in the USA and reported quitting smoking in 2010. The survey’s respondents who never smoked or reported current smoking in 2010 were excluded from the study sample.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Smoking relapse was defined as picking up smoking in 2011 after reporting smoking abstinence in 2010. The prevalence of relapse over the 12-month follow-up period was estimated among different subgroups. Multivariable logistic regression models were applied to determine factors associated with relapse.

Results

A total of 184 former smokers reported smoking relapse by 2011 (weighted prevalence 6.8%; 95% CI 5.7% to 8.1%). Prevalence and odds of relapse were higher among young people compared with elders. Former smokers living in smoke-free homes (SFHs) had 60% lower odds of relapse compared with those living in homes that allowed smoking inside (adjusted OR 0.40; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.64). Regarding race/ethnicity, only Hispanics showed significantly higher odds of relapse compared with Whites (non-Hispanics). Odds of relapse were higher among never married, widowed, divorced and separated individuals, compared with the married group. Continuous smoking cessation for 6 months or more significantly decreased odds of relapse.

Conclusions

Wider health determinants, such as race and age, but also living in SFHs showed significant associations with smoking relapse, which could inform the development of more targeted programmes to support those smokers who successfully quit, although further longitudinal studies are required to confirm our findings.

Keywords: public health, smoking, prevention and control

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The data were retrieved from a longitudinal study, which is suitable for studying smoking relapse as a behaviour that develops over time after cessation.

We used data from the most recent longitudinal survey of the Tobacco Use Supplement-Current Population Survey (2010–2011) which is relatively old.

Results should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small sample size in some subgroups.

Some factors found to be associated with relapse in earlier studies were not available in the data set to be included in the regression models.

Due to the inconsistent definitions of smoking relapse in the literature, sensitivity analyses were conducted using different cut-off points for the duration of smoking cessation.

Introduction

The WHO estimates that there are 1.1 billion current smokers worldwide.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 37.8 million adults were active smokers in the USA in 2016, representing more than 15.5% of the total US population.2 Annually, smoking leads to 480 000 deaths in the USA,3 and its related hazards cost approximately 1% of the country’s gross domestic product.4 5

The prevalence of smoking is determined by the proportion of the non-smoking population that initiates smoking, and the proportion of smokers who die or quit. Most tobacco control programmes aim to reduce smoking prevalence by preventing smoking initiation and promoting cessation; however, long-term cessation remains challenging. Although research on smoking cessation is abundant, most studies have explored factors associated with quit intentions and overall determinants of smoking abstinence,6–8 with only a few focusing on ‘relapsing’; that is, restarting smoking after a temporarily successful cessation attempt.

Despite variations in the definitions used in the literature, smoking relapse essentially means picking up smoking after a period of abstinence.9 In past research, relapse rates within the first year of abstinence ranged from 60% to 90%, while 2 years of continuous cessation indicated a likelihood of 80% to maintain long-term abstinence.10 In this study, we use cigarette smoking to define relapse, as it is the most common method of tobacco use in the USA and globally (>90%).9 Thus, ‘smoking’ refers to ‘cigarette smoking’.

Although relapse has rarely been the specific focus of smoking cessation research, it is reasonable to assume that at least some of the factors found to be associated with smoking cessation overall also play a role in the process of relapse. Previous studies have reported a link between genetic factors and smoking behaviours.11 Other personal characteristics have been highlighted in relevant studies, including age,12 sex,13 race/ethnicity14 and nicotine dependence.15 Researchers have previously shown that knowledge and perceptions of smoking hazards influence individual intentions and motivations to quit or relapse.16 17 Recent studies indicated the influence of community factors and support given to smokers on their determination and willingness to quit.18 19 There is also evidence with regard to the impact of living in a smoke-free home (SFH),20 using non-cigarette tobacco products (NCTP)21–23 and seeking specialist advice for quitting on smoking behaviours.24 Additionally, research showed that smokers newly diagnosed with chronic diseases, such as obstructive lung diseases, were more likely to quit smoking.25 26

Nevertheless, there is a scarcity of studies assessing determinants of smoking relapse in particular, which remains an under-researched area. To fill this gap, this study aimed to measure the prevalence of cigarette smoking relapse among adult former smokers in the USA and to determine predictors of relapse using a nationally representative longitudinal sample.

Methods

Data source

We conducted a secondary analysis of longitudinal data retrieved from the Tobacco Use Supplement-Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS). This survey has been conducted every 3–4 years in the USA since 1992. It collects a broad range of data about the US population with topics varying from year to year. For this study, we used a longitudinal sample of the survey; the cohort baseline data were collected in May 2010 and the follow-up survey was conducted in May 2011. It focused on the population’s smoking behaviours and cessation attitudes. No other data were recorded between these two time points.27 28

Selection of TUS-CPS respondents is designed to yield representative estimates for the USA overall, as well as the 50 states and Washington, DC.29 30 Since 2006, the survey has targeted US adults aged 18 years and above.28 29 The cohort of 2010–2011 was the most recent longitudinal sample of the survey that assessed the outcome of interest, smoking relapse. Data were collected by telephone or in-person interviews.29 In this particular cohort, 64% of participants completed the survey through telephone interviews and 36% through in-person interviews.27 29 Approximately 20% of the data were recorded by proxy, while the rest was self-reported.29 For this research project, we only used data collected from self-respondents.

The analysis sample comprised individuals who reported being former smokers at baseline (May 2010 survey wave). Their smoking status was self-reported again after 1 year (May 2011). Relapse was defined as a failure to maintain smoking cessation between the two time points of data collection in the TUS-CPS surveys. Those who didn’t report their smoking status in either wave or provided inconsistent data regarding having ever smoked between the two waves were excluded from the analysis. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the final study sample was 3258, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrates the steps of selecting the study sample based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Measures

Cigarette smoking relapse status is the principal outcome of this study. Participants were asked to report their smoking status in 2010 and 2011: ‘Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days or not at all?’ Responses were categorised into a dichotomous variable (yes (every day or some days) and no (not at all)). Those who responded ‘not at all’ in 2010, but ‘every day’ or ‘some days’ in 2011 were considered to have relapsed. Daily and non-daily smokers were grouped together as it has been shown that even very low cigarette consumption is associated with significant health risks.31

Sociodemographic variables included age (18–24, 25–39, 40–65 and ≥65 years); sex (male and female); race/ethnicity (Hispanics, White non-Hispanics, Black non-Hispanics and other non-Hispanics); education level, determined by the highest accomplished level (<high school, high school, some college, defined as partially completed college education, and college or higher); and finally, socioeconomic status, reflected by annual family income (US$<20k, 20–49k, 50–99k and ≥100k). Categorising these variables was based on previously published reports and studies using the TUS-CPS surveys.32

This study used 6 months of continuous smoking abstinence as a cut-off point for defining sustained cessation (ie, former smokers), guided by previous relevant studies.33 The participants were asked in 2010 to answer: ‘About how long has it been since you completely quit smoking cigarettes?’.34 Answers equal to or higher than 26 weeks or 180 days were counted as 6 months or longer. Participants who responded ‘don’t know’ or refused to answer were excluded from the analysis (n=28).

In 2010, the participants were asked: ‘Which statement best describes the rules about smoking inside your home? No one is allowed to smoke anywhere inside your home; smoking is allowed in some places or sometimes inside your home; or smoking is permitted anywhere inside your home’.34 Those who stated that no one is allowed to smoke anywhere inside their home were classified as living in an SFH. All other respondents were classified as living in a non-SFH.

Use of four NCTPs was investigated in this study as factors potentially associated with cigarette smoking relapse: cigar, regular pipes, water pipes and smokeless tobacco. Participants were asked: ‘Have you ever used any of the following even one time? (The four investigated NCTP were mentioned in separate questions)’. A composite variable was created considering the use of any NCTP. Those who reported ever use of any of those products were classified as ‘ever users’. Those ‘ever users’ were also asked: ‘Do you NOW use a ‘NCTP’ every day, some days or not at all?’. The answers used to classify them into current and former users.34

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of smoking relapse was estimated among the whole cohort and within each subgroup. Logistic regression models were fitted to investigate unadjusted and adjusted associations between smoking relapse and a set of factors. The dependent variable of all logistic regression models was smoking relapse status. Factors identified as potentially relevant in the existing literature were considered for inclusion in the models. The final specification of the models was decided based on an iterative approach using the Akaike information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion. The significance level was set at 0.05. The official weights provided in the original data sets were used to account for the complexity of the TUS-CPS design. The analysis was performed using Stata V.13.1. Missing observations and those with inconsistent ever smoking status in the follow-up survey were excluded from the analysis.

Due to the varied definitions of smoking relapse in the literature, sensitivity analyses were conducted using different cut-off points for the duration of smoking cessation. Binary variables using 1 and 3 months as cut-off points were included into two separate models. Additionally, a separate model was fitted using four distinct periods of smoking cessation: less than 1 month, 1–3 months, 3–6 months, and 6 months or more. Reporting 30 days of abstinence was counted as 1 month; 13 weeks or 90 days was counted as 3 months; and 26 weeks or 180 days was counted as 6 months.

Patient and public involvement

It was not applicable to directly involve the public in this research project as it was a secondary data analysis. Consents were deemed unnecessary for this study under national regulations.

Results

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, only 3258 of the 18 499 participants who answered both TUS-CPS surveys in 2010 and 2011 were included in the final analysis. We excluded 55 participants from the analysis due to missing observations.

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the final study population based on their self-reported answers in the baseline survey. Prevalence estimates were 2.6%, 0.7%, 0.04% and 2.5% for ever-use of cigars, regular pipes, water pipes and smokeless tobacco products, respectively. Former users of any NCTP accounted for 37.2% among all participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the baseline former smokers’ cohort, based on the self-reported answers in the TUS-CPS 2010 survey, in the USA (n=3258)

| N* | Weighted (%)† | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1639 | 57.3 |

| Female | 1619 | 42.7 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 65+ | 1078 | 31.5 |

| 40–64 | 1672 | 48.3 |

| 25–39 | 472 | 17.3 |

| 18–24 | 36 | 2.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White (non-Hispanics) | 2859 | 83.9 |

| Black (non-Hispanics) | 172 | 6.0% |

| Other (non-Hispanics) | 101 | 3.6 |

| Hispanics | 126 | 6.6 |

| Annual family income (US$) | ||

| <20k | 494 | 15.6 |

| 20–49k | 1110 | 34.8 |

| 50–99k | 1073 | 32.4 |

| 100k+ | 581 | 17.3 |

| Education level | ||

| <High school | 356 | 11.8 |

| High school | 977 | 29.4 |

| Some college‡ | 1574 | 48.1 |

| College+§ | 351 | 10.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1872 | 57.7 |

| Widowed | 402 | 11.3 |

| Divorced | 576 | 16.3 |

| Separated | 48 | 1.9 |

| Never married | 360 | 12.7 |

| Non-cigarette tobacco products (NCTP) use | ||

| Never user | 1920 | 57.2 |

| Current user | 159 | 5.6 |

| Former user | 1144 | 37.2 |

| Smoking cessation period, months | ||

| <6 | 127 | 4.8 |

| ≥6 | 3103 | 95.2 |

| Living in smoke-free home (SFH) | ||

| Non-SFH | 463 | 14.6 |

| SFH | 2738 | 85.4 |

| Smoke-free workplace | ||

| Indoor smoking allowed | 175 | 6.3 |

| Indoor smoke-free | 950 | 31.9 |

| Outdoor | 125 | 4.7 |

| Undetermined | 208 | 6.6 |

| Not employed | 1530 | 50.5 |

| Total | 3258 | 100 |

Counts and percentages in this table include only completed answers in each variable, excluding missing observations; 28 were missed in smoking cessation period, 57 in SFH and 270 in smoke-free workplace.

*Number of participants.

†Using official weights to ensure the sample is representative of the source population.

‡Partially completed college education.

§Completed a college education or higher.

TUS-CPS, Tobacco Use Supplement-Current Population Survey.

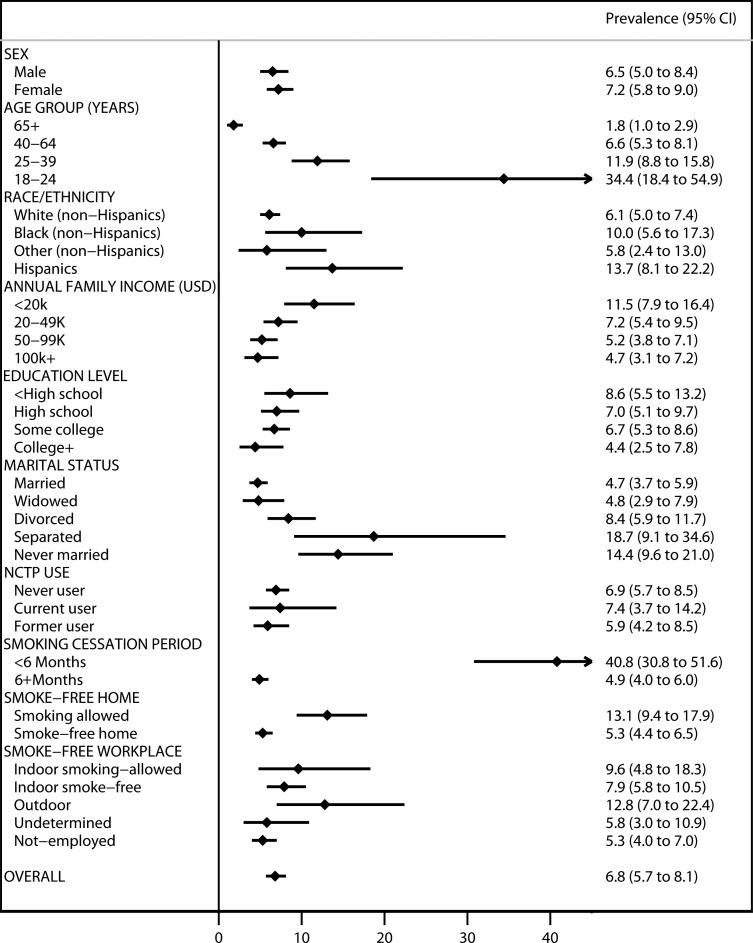

Figure 2 shows weighted prevalence of relapse among different subgroups. Out of 3258 former smokers in 2010, a total of 184 reported smoking relapse by May 2011. They represented 6.8% (95% CI 5.7% to 8.1%) of the cohort. The prevalence of smoking relapse was lower than 20% in all subgroups, except among people aged 18–24 years (34.4%; 95% CI 18.4% to 54.9%) and among those who reported smoking abstinence for less than 6 months prior to the baseline survey (40.8%; 95% CI 30.8% to 51.6%).

Figure 2.

Weighted prevalence of smoking relapse former smokers in the TUS-CPS 2010–2011 cohort surveys in the USA (n=3258). Weighted prevalence has incorporated official weights to ensure that the sample is representative of the source population. College+, completed a college education or higher; NCTP, non-cigarette tobacco products; OVERALL, overall prevalence of relapse among all participants; Some college, partially completed college education; TUS-CPS, Tobacco Use Supplement-Current Population Survey.

Table 2 presents the results of the unadjusted and final adjusted multivariable logistic regression models exploring associations of smoking relapse with individual and environmental factors among the study population. Despite the limited number of Hispanic participants, they were more likely to relapse compared with White non-Hispanics (adjusted OR (aOR) 2.05; 95% CI 1.03 to 4.08). The likelihood of relapse was also significantly associated with age. After adjusting for all the other variables, the youngest age group (18–24 years) still had the highest odds of relapse among all subgroups (aOR compared with the oldest group: 15.75; 95% CI 4.23 to 58.42). Sex showed no significant association with smoking relapse, although there is some suggestion that males were less likely to relapse.

Table 2.

Predictors of smoking relapse among the US adult former smokers, data extracted from the TUS-CPS 2010–2011 cohort surveys (n=3182)

| Independent variables | Unadjusted OR (lower and upper limits of 95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (lower and upper limits of 95% CI) |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 65+ (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 40–64 | 3.95 (2.23 to 6.99) | 4.28 (2.19 to 8.37) |

| 25–39 | 7.56 (4.05 to 14.10) | 8.09 (3.72 to 17.62) |

| 18–24 | 29.40 (10.89 to 79.37) | 15.75 (4.25 to 58.42) |

| Sex | ||

| Female (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 0.89 (0.62 to 1.28) | 0.91 (0.61 to 1.37) |

| Smoking cessation period, months | ||

| <6 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥6 | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.12) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.23) |

| Living in SFH | ||

| Non-SFH (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| SFH | 0.37 (0.25 to 0.58) | 0.40 (0.25 to 0.64) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Widowed | 1.03 (0.58 to 1.86) | 2.77 (1.31 to 5.84) |

| Divorced | 1.86 (1.18 to 2.92) | 2.34 (1.42 to 3.85) |

| Separated | 4.67 (1.96 to 11.18) | 4.16 (1.65 to 10.52) |

| Never married | 3.42 (2.03 to 5.79) | 1.48 (0.82 to 2.67) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White (non-Hispanics) (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Black (non-Hispanics) | 1.72 (0.88 to 3.36) | 0.94 (0.44 to 2.02) |

| Other (non-Hispanics) | 0.94 (0.38 to 2.36) | 0.81 (0.30 to 2.19) |

| Hispanics | 2.45 (1.31 to 4.57) | 2.05 (1.03 to 4.08) |

Smoking relapse is the only outcome. The ORs in this table are all weighted. Adjusted OR is adjusted for all variables in the table. AIC value: 1134.57 and BIC value: 1219.49.

AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion; ref, reference group; SFH, smoke-free home; TUS-CPS, Tobacco Use Supplement-Current Population Survey.

Widowed and divorced former smokers had 2.77 (95% CI 1.31 to 5.84) and 2.34 (95% CI 1.41 to 3.85) times the odds of relapse compared with the married group, respectively. Separated individuals had approximately four times the odds of relapse compared with married respondents (aOR 4.16; 95% CI 1.65 to 10.52). Living in a home where smoking inside was prohibited reduced the odds of relapse by 60% compared with living in homes where smoking was allowed (aOR 0.40; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.64).

Additionally, the adjusted model showed that smoking cessation for 6 months or more was a robust predictor of not relapsing, even after adjusting for the other variables. Those who reported smoking abstinence for more than 6 months had 87% lower odds of relapse compared with the group who had quit smoking for less than 6 months at the time of the 2010 survey (aOR 0.13; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.23).

The sensitivity analyses using different cut-off points for the cessation period prior to the baseline survey (online supplementary tables S1-S3) consistently showed that longer periods of prior abstinence were strongly associated with lower odds of relapse.

bmjopen-2019-031676supp001.pdf (73KB, pdf)

Discussion

Our analysis estimated the overall prevalence of smoking relapse among US former smokers between 2010 and 2011 at 6.8%, although this figure varied widely among population subgroups. Five factors had significant associations with relapse: duration of smoking cessation; living in SFHs; marital status; age and race/ethnicity.

The estimated prevalence of relapse in this study was consistent with a previous meta-analysis reporting relapse after 1 year of smoking abstinence which reported this figure to be between 5% and 17%.35 A study comparing US and UK former smokers found that adults living in the USA were more likely to relapse in less than 28 days of abstinence.36 Americans are slightly younger in age and more ethnically and racially diverse,37 which based on the findings of our study may explain some of these differences.

We found a significant association between duration of smoking cessation and relapse, which shows that the longer it’s been since quitting, the easier it gets to remain quit. This highlights that quitters may require extra support during the critical early days after stopping. This association could be primarily explained by the addictive characteristics of nicotine, the effect of which is attenuated following a relatively short period of abstinence.38 Moreover, psychosocial, financial and cultural factors increase the risk of relapse particularly during the first 6 months of quitting.33 Another study found that 3 months of continuous abstinence is the critical period after which the likelihood of successful quitting increases, which is consistent with our main and sensitivity analyses.39 However, the cessation periods calculated in this study only refer to the time prior to the first data collection point. We did not have data on the length of the abstinence period between the baseline survey and the exact time of relapse; hence, the actual period of abstinence may differ from what we used in our analyses, although we have no reason to believe that this may have introduced systematic error in our analysis.

Living in an SFH decreased the odds of relapse for former smokers by 60%. Previous studies have reported a 40% reduction in odds of relapse among similar groups.20 A previous cohort study showed that members of households banning smoking had a 12% higher likelihood to successfully quit smoking.20 The impact of SFH on smoking behaviours is consistent among disadvantaged populations, such as low-income smokers,40 highlighting the influence of the immediate social and physical environment on smoking behaviours. Along the same lines, having a partner who is a former or current smoker may affect quitting decisions of the spouse.41 Losing a partner may demotivate quitters from successfully maintaining smoking cessation.16 17 33 Additionally, being separated, divorced or widowed might drive a general feeling of insecurity and anxiety,42 43 which could explain the higher rates of relapse found among these subgroups in our analysis.

We also found that young adults were the most likely to relapse among all subgroups. Young adults have more opportunities to smoke in groups during parties, festivals and celebrations44 and are more vulnerable to peer pressure which makes them more susceptible to smoking relapse after cessation.45 Younger smokers may also underestimate the health consequences of smoking, which may weaken their determination to quit.17 Older individuals in our sample were also more likely to have quit many years earlier, which, as highlighted before, is a robust predictor of sustained abstinence.

Hispanics had higher odds of relapse compared with non-Hispanic groups. Hispanics in the USA are more likely to be affected by health inequalities due to health insurance challenges, economic burden and cultural sensitivity.46 47 These disparities are manifested in and may be compounded by their lower success in quitting compared with Whites, which perpetuates social and health inequality in the USA.

This study sheds light on smoking relapse and provides an insight into its predictors in a representative sample of the adult US population. Using a longitudinal design allowed us to explore smoking relapse over the course of 12 months. However, the tobacco products environment has changed considerably since 2011; therefore, our findings may not fully reflect the current conditions in the USA.

The questions of TUS-CPS were not originally designed to study smoking relapse as an outcome; for example, the exact time point of relapse was not reported which may have led to inaccurate estimates for some individuals; it is unclear whether any such inaccuracies may have followed a pattern that could influence the results. The scope of the study was also not broad enough to investigate some factors shown to have significant associations with smoking relapse in previous studies, such as genetic factors11 and perceptions regarding smoking hazards.16 17

Relying only on self-reported data and the relatively high frequency of inconsistent reporting of ever smoker status between the two waves of the survey may have introduced selection bias which would have an impact on the representativeness of the study sample. Moreover, although the original sample size of TUS-CPS was large, our analytical sample was smaller; hence, findings in certain subgroups, such as the Hispanics, should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, the overall sample was originally weighted in the main data set to be representative of the national population.

Our analysis contributes to the limited literature on the epidemiology of smoking relapse at the population level. Further studies could explore the magnitude of the problem among high-risk groups and in other populations, as well as more factors associated with relapse. Our findings can also inform tobacco control policies and specific interventions targeting those recent quitters who are at the highest risk of relapse, especially among vulnerable groups.

Conclusion

Smoking prevalence is a function of multiple parameters, such as initiation, cessation and relapse. Of these parameters, smoking relapse has been the least investigated. The prevalence of relapse within a 1 year period was estimated at 6.8% in this study. We found that age, race/ethnicity, marital status, duration of smoking cessation and living in SFHs were associated with smoking relapse among adults in the USA, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to reduce relapse and increase long-term success of quit attempts. Further research purposefully designed to monitor and investigate relapse should be directed to explore determinants of relapse among different populations, and at various points in time following cessation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The first author, AA, conducted the data analysis, reported results and wrote the first draft of the study manuscript. The second and third authors, ITA and SO, helped in cleaning the data and guided the analysis from their previous experience in analysing data from the used survey. The fourth author, FTF, with the first author proposed the research question and provided support for designing and coordinating the research project, in addition to contributing in writing the final manuscript of the study. All the authors significantly contributed to the research project and agreed on its all aspects.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was deemed unnecessary for this study under national regulations.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Global action on patient safety for achieving effective universal health coverage. 71th World health assembly World Health organization, 2018. [Accessed 22 May 2018].

- 2. Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1225–32. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Warren GW, Alberg AJ, Kraft AS, et al. The 2014 Surgeon General’s report: ‘The health consequences of smoking–50 years of progress’: a paradigm shift in cancer care. Cancer 2014;120:1914–6. 10.1002/cncr.28695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ekpu VU, Brown AK. The economic impact of smoking and of reducing smoking prevalence: review of evidence. Tob Use Insights 2015;8:1–35. 10.4137/TUI.S15628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Smoking-Attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses – United States, 2000–2004: centers for disease control and prevention. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5745a3.htm [Accessed 5 Jul 2018].

- 6. Chezhian C, Murthy S, Prasad S, et al. Exploring factors that influence smoking initiation and cessation among current smokers. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9:LC08–12. 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12047.5917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cantrell J, Bennett M, Mowery P, et al. Patterns in first and daily cigarette initiation among youth and young adults from 2002 to 2015. PLoS One 2018;13:e0200827 10.1371/journal.pone.0200827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reyes-Guzman CM, Pfeiffer RM, Lubin J, et al. Determinants of light and intermittent smoking in the United States: results from three pooled National health surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:228–39. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arizona Department of Health Services Smoking relapse: what to do if you start smoking again: ash line website, 2017. Available: https://ashline.org/es/smoking-relapse-what-to-do-if-you-start-smoking-again/

- 10. Krall EA, Garvey AJ, Garcia RI. Smoking relapse after 2 years of abstinence: findings from the Va normative aging study. Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4:95–100. 10.1080/14622200110098428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lerman CE, Schnoll RA, Munafò MR. Genetics and smoking cessation improving outcomes in smokers at risk. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:S398–405. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, et al. Quitting Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;65:1457–64. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McKee SA, Maciejewski PK, Falba T, et al. Sex differences in the effects of stressful life events on changes in smoking status. Addiction 2003;98:847–55. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sakuma K-LK, Felicitas-Perkins JQ, Blanco L, et al. Tobacco use disparities by racial/ethnic groups: California compared to the United States. Prev Med 2016;91:224–32. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, et al. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction 2011;106:2110–21. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borland R, Yong H-H, Balmford J, et al. Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: findings from the International tobacco control four country project. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12(Suppl):S4–11. 10.1093/ntr/ntq050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. El-Khoury Lesueur F, Bolze C, Melchior M. Factors associated with successful vs. unsuccessful smoking cessation: data from a nationally representative study. Addict Behav 2018;80:110–5. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. ARotS G. Social, environmental, cognitive, and genetic influences on the use of tobacco among youth, 2012. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99236/

- 19. Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychol Bull 1995;117:67–86. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hyland A, Higbee C, Travers MJ, et al. Smoke-Free homes and smoking cessation and relapse in a longitudinal population of adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:614–8. 10.1093/ntr/ntp022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Connor RJ. Non-cigarette tobacco products: what have we learnt and where are we headed? Tob Control 2012;21:181–90. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cornacchione Ross J, Noar SM, Sutfin EL. Systematic review of health communication for Non-Cigarette tobacco products. Health Commun 2019;34:361–9. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1407274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhuang Y-L, Cummins SE, Sun JY, et al. Long-term e-cigarette use and smoking cessation: a longitudinal study with us population. Tob Control 2016;25:i90–5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Song F, Maskrey V, Blyth A, et al. Differences in longer-term smoking abstinence after treatment by specialist or Nonspecialist advisors: secondary analysis of data from a relapse prevention trial. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1061–6. 10.1093/ntr/ntv148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danielsen SE, Løchen M-L, Medbø A, et al. A new diagnosis of asthma or COPD is linked to smoking cessation - the Tromsø study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:1453–8. 10.2147/COPD.S108046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patel K, Schlundt D, Larson C, et al. Chronic illness and smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:933–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntp088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naitonal Cancer Institute DoCCPS What is the TUS-CPS? 2018. Available: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/tus-cps/

- 28. National Cancer Institute Tobacco use supplement, 2018. Available: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/tus-cps/TUS-CPS_fact_sheet.pdf?file=/studies/tus-cps/TUS-CPS_fact_sheet.pdf

- 29. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Tobacco use supplement-current population survey, 2012. Available: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-source/tobacco-use-supplement-current-population-survey [Accessed 28 Jul 2018].

- 30. Wang Y, Sung H-Y, Yao T, et al. Factors associated with short-term transitions of non-daily smokers: socio-demographic characteristics and other tobacco product use. Addiction 2017;112:864–72. 10.1111/add.13700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hackshaw A, Morris JK, Boniface S, et al. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ 2018;360 10.1136/bmj.j5855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Cancer Institute-Division of Cancer Control & Populaiton Sciences Reports & Publications Using the TUS-CPS, 2018. Available: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/tus-cps/publications.html [Accessed 16 Jul 2018].

- 33. Yong H-H, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Do predictors of smoking relapse change as a function of duration of abstinence? findings from the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Australia. Addiction 2018;113:1295–304. 10.1111/add.14182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Cancer Institute - Tobacco Control Research Branch 2010-2011 tobacco use supplement to the current population survey, 2013. Available: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/tus-cps/surveys/tuscps_english_2010.pdf [Accessed 12 Jul 2018].

- 35. Hughes JR, Peters EN, Naud S. Relapse to smoking after 1 year of abstinence: A meta-analysis. Addict Behav 2008;33:1516–20. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gibson JE, Murray RL, Borland R, et al. The impact of the United Kingdom's national smoking cessation strategy on quit attempts and use of cessation services: findings from the International tobacco control four country survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12(Suppl):S64–71. 10.1093/ntr/ntq119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tunstall RK. Americans and Britons: key population data from the last three U.S. and U.K. Censuses. Brookings Website: Brookings Inc, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Georgiadou C, Lavdaniti M, Psychogiou M, et al. Factors affecting the decision to quit smoking of the participants of a hospital-based smoking cessation program in Greece. J Caring Sci 2015;4:1–11. 10.5681/jcs.2015.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burke MV, Hays JT, Ebbert JO. Varenicline for smoking cessation: a narrative review of efficacy, adverse effects, use in at-risk populations, and adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:435–41. 10.2147/PPA.S83469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vijayaraghavan M, Messer K, White MM, et al. The effectiveness of cigarette price and smoke-free homes on low-income smokers in the United States. Am J Public Health 2013;103:2276–83. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takagi D, Kondo N, Takada M, et al. Differences in spousal influence on smoking cessation by gender and education among Japanese couples. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1184 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rodriguez LM, DiBello AM, Øverup CS, et al. The price of distrust: trust, anxious attachment, jealousy, and partner abuse. Partner Abuse 2015;6:298–319. 10.1891/1946-6560.6.3.298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee for the Study of Health Consequences of the Stress of Bereavement Reactions to Particular Types of Bereavement : Osterweis M, Solomon F, Green M, Bereavement: reactions, consequences, and care. Washington, DC, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health Social, environmental, cognitive, and genetic influences on the use of tobacco among youth, 2012. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99236/

- 45. Collins SE, Witkiewitz K, Kirouac M, et al. Preventing relapse following smoking cessation. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2010;4:421–8. 10.1007/s12170-010-0124-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E. Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiol Rev 2009;31:99–112. 10.1093/epirev/mxp008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG, et al. Hispanic health in the USA: a scoping review of the literature. Public Health Rev 2016;37 10.1186/s40985-016-0043-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031676supp001.pdf (73KB, pdf)