Abstract

Objectives

Women with high body mass index (BMI) have increased risk for symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and postpartum. In this prespecified secondary analysis from the exercise training in pregnancy trial, our aim was to examine effects of supervised exercise during pregnancy on psychological well-being in late pregnancy and postpartum among women with a prepregnancy BMI ≥28 kg/m2.

Design

Single-centre, parallel group, randomised controlled trial.

Setting

University Hospital, Norway.

Participants

Ninety-one women (age 31.2±4.1 years, BMI 34.5±4.2 kg/m2), 46 in the exercise group, 45 in the control group, were included in the trial.

Intervention

The exercise group was offered 3 weekly supervised exercise sessions (35 min of moderate intensity walking/running and 25 min of resistance training), until delivery.

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

Primary analyses were based on intention to treat, with secondary perprotocol analyses. To assess psychological well-being, we used the ‘Psychological General Well-Being Index’ (PGWBI) at inclusion (gestational week 12–18), late pregnancy (gestational week 34–37) and 3 months postpartum. We assessed postpartum depression using the ‘Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale’ (EPDS).

Results

Numbers completed data collection: late pregnancy 72 (exercise 38, control 36), postpartum 70 (exercise 36, control 34). In the exercise group, 50% adhered to the exercise protocol. Baseline PGWBI for all women was 76.4±12.6. Late pregnancy PGWBI; exercise 76.6 (95% CI 72.2 to 81.0), control 74.0 (95% CI 69.4 to 78.5) (p=0.42). Postpartum PGWBI; exercise 85.4 (95% CI 81.9 to 88.8), control 84.6 (95% CI 80.8 to 88.4) (with no between-group difference, p=0.77). There was no between-group difference in EPDS; exercise 2.96 (95% CI 1.7 to 4.2), control 3.48 (95% CI 2.3 to 4.7) (p=0.55).

Conclusions

We found no effect of supervised exercise during pregnancy on psychological well-being among women with high BMI. Our findings may be hampered by low adherence to the exercise protocol.

Trial registration number

Keywords: maternal health, mental health, depression, anxiety, pregnancy complications

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was a randomised controlled trial.

The exercise programme was supervised.

The trial assessed psychological well-being at multiple time points; in early pregnancy, late pregnancy and 3 months postpartum.

The trial was limited by a lower number of participants than originally planned.

The trial was limited by relatively low adherence to the exercise intervention.

Introduction

About 20% of pregnant women report reduced psychological well-being and symptoms of depression and anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum.1–3 The prevalence of reduced psychological well-being among pregnant women who are overweight and obese is found to be even higher; about 30%.1 2 4–8 For the purpose of this paper, psychological well-being is defined as ‘people’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives; happiness, absence of negative emotions (eg, depression, anxiety), satisfaction with life, and positive functioning’.9 Postnatal depression can be defined as ‘a type of clinical depression that occurs after childbirth’.10 Reduced psychological well-being may develop early in pregnancy and symptoms of anxiety and depression in pregnancy or postpartum are associated with increased risk for complications, for example, hypertension, preterm birth, infant small for gestational age, lower rates of breastfeeding and impaired mother–newborn interaction.11–15 These complications adds to other well-documented maternal and foetal risks for women with obesity; such as gestational diabetes, maternal hypertension, pre-eclampsia and infants born large for gestational age.16–21 Therefore, it is important to find strategies to prevent poor psychological well-being during pregnancy and the postpartum period for women with obesity.

Regular physical activity and/or supervised exercise training is beneficial for psychological well-being,22–24 and contributes to reduced depressive symptoms among previously inactive individuals.24 Pregnant women are, equal to the general population, advised to perform regular exercise and be physically active,25 but the frequency and intensity of exercise and physical activity tend to decline during pregnancy, especially among overweight and obese women.26 Observational studies show that maternal exercise and physical activity are positively associated with better psychological well-being and reduced risk for postnatal depression.27 28 However, results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the effect of exercise training on psychological well-being diverge.29–31

In the exercise training in pregnancy (ETIP) trial, we determined the effect of offering supervised exercise training during pregnancy on maternal and foetal outcomes among 91 women with overweight or obesity, where gestational weight gain was our primary outcome measure.32–35 In this prespecified,35 secondary analysis of the ETIP trial, we aimed to determine the effect of exercise training on self-perceived psychological well-being in late pregnancy and 3 months postpartum, and the effect of ETIP on the risk for postnatal depression.

Methods

Trial design

The ETIP trial was a single-centre, parallel-group RCT where we determined the effects of offering overweight and obese women supervised exercise training during pregnancy compared with standard maternal care only. The trial was undertaken at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Norway. We started inclusion of participants in September 2010, with the last assessments in November 2015. The ETIP trial protocol and detailed description of the methods have been published elsewhere.32 35 The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK-midt 2010/1522) and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. The ETIP trial was submitted to clinical trials 6 September 2010 with the Study Start Date set to September 2010 (Please see attached PRS Review Comments). Clinical trials responded with a comment that they wanted us to respond to, and therefore did not release the trial immediately. Due to a delay at our faculty’s administration, the response to the comment was not submitted until November 2010.

Participants

We included women with prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) ≥28 kg/m2, ≥18 years, in gestational week 12–18, and carrying a singleton live fetus at an 11-week to 14-week ultrasound scan. Categorisation of overweight and obesity was based on the WHO classification system.36 Prepregnancy BMI was self-reported. Participants had to attend assessments and exercise classes at St. Olavs Hospital. Our exclusion criteria were: high risk of preterm birth, diseases that could interfere with participation, habitual exercise training at baseline (defined as exercising twice or more weekly in the period before inclusion). The women received written information and signed informed consent on behalf of themselves and their offspring before inclusion. We recruited participants through invitations sent along with notices for routine ultrasound scan appointments, information sent to general practitioners, and through Google advertisements. At the last study visit, the women received infant food worth 500 Norwegian kroner.

Intervention

All participants, regardless of group allocation, received maternity and postpartum care according to the Norwegian Standard Maternity Care for pregnant women, which is offered to all (free of charge).37

Women in the exercise group were offered supervised exercise sessions at St. Olavs Hospital three times weekly from inclusion until delivery. The exercise programme was in accordance with the recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists25 38 39 and from the Norwegian Directorate of Health for physical activity during pregnancy.40 The exercise sessions were supervised by a physical therapist and consisted of 35 min of treadmill walking at ~80% of maximal aerobic capacity (corresponding to Borg scale 12–15)35 followed by 25 min of resistance training, including pelvic floor muscle training. In addition to the supervised programme, we asked the women to exercise at home for 50 min at least once weekly, and to do daily pelvic floor muscle exercises. For a full description of the exercise intervention, see previous reports (see online supplementary file 1).32 35 Adherence to the exercise programme was registered in a training diary. Women in the control group were not discouraged from physical activity or exercise.

bmjopen-2018-028252supp001.pdf (270.1KB, pdf)

Outcomes

Sociodemographic data were collected by self-reported questionnaires at baseline assessments. Information regarding the participants’ psychological well-being and risk of postnatal depression was assessed by self-reported questionnaires, completed at the hospital while they underwent a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test at baseline, late pregnancy and 3 months postpartum, with trial researchers available to clarify questions if needed.

Psychological well-being was assessed by the ‘Psychological General Well-Being Index’ (PGWBI) questionnaire (PGWBI 1984 Harold J. Dupuy, Mapi Research Trust)41 42 at baseline (gestational week 12–18), in late pregnancy (gestational week 34–37) and 3 months postpartum. PGWBI measures self-perceived psychological health and general well-being during the last week, and intends to assess health-related quality of life or, said otherwise, to reflect a sense of well-being or distress that includes positive and negative intrapersonal affective or emotional states.35 PGWBI consists of 22 items with 6-point self-response scales that range from 0 (=most negative option) to 5 (=most positive option). The questionnaire includes six non-overlapping dimensions: anxiety (five items), depressed mood (three items), positive well-being (four items), self-control (three items), general health (three items) and vitality (four items).35 38 Each dimension is summed and the total (maximum=110) forms the overall PGWBI. The anxiety dimension assesses whether the subjects are bothered by nervousness, were generally tense, anxious, worried or upset, and/or under stress strain or pressure. Depressed-mood assesses if the participants are depressed, hopeless or downhearted and ‘blue’. Positive well-being indicates the general spirit, cheerfulness, or happiness and satisfaction with personal life. The self-control dimension intends to measure whether the subjects feel emotionally stable, in firm control, or afraid of losing control. The general health dimension assesses if the subjects are bothered with pain, disorder or illness and whether they are healthy enough ‘to do things’. Finally, the vitality dimension contains items that assess the participants’ energy, whether they feel active, vigorous, or sluggish, tired and worn out.35

The PGWBI questionnaire is a generic questionnaire frequently used in clinical trials across many conditions, and translated to several languages.43–46 The PGWBI has been found suitable for subjects 14–90 years and is a highly preferred self-administered inventory.35 The internal consistency reliability is high, with Cronbach’s alpha correlations between 0.90 and 0.94.35 Similar correlations (Cronbach’s alpha >0.90) have been shown for tests done in Sweden,43 with culture and language similar to the Norwegian,44 and recently used by Gustafsson and colleges in a clinical trial among Norwegian pregnant women.29 The present Norwegian version of the questionnaire was translated by a standard forward–backward method at St. Olavs Hospital, the university Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, in February 2002.47

To measure the prevalence of symptoms of postnatal depression, the participants also completed the ‘Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale’ (EPDS) questionnaire.48 The EPDS questionnaire is a non-generic self-rating scale, which measures the presence of depressive symptoms during the postpartum period, indicating how the mother has felt during the last week.48 49 The EPDS questionnaire contains 10 questions. All questions contain four response alternatives where the women are asked to ‘please underline the answer which comes closest to how you have felt in the past 7 days’.48 We estimated total score of the 10 items using a scoring system from 0 to 3, with 0 representing the most negative option, and 3 the most positive option. Based on validations of the questionnaire,48 we used a cut-off score of 10–12 as indication of minor depression and ≥13 as indication of major depression. The EPDS questionnaire is developed and commonly used for measurement of depressive symptoms in the postpartum period, but is also used and validated for the pregnancy period.48 The questionnaire is translated to Norwegian and valid to detect postpartum depression in a Norwegian population.50 51

Additionally, the participants reported their self-perceived general health status at baseline and in late pregnancy as either ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘either good or bad’, ‘quite bad’ or ‘bad’. This question is taken from the SF 36 Short Form Health Survey. This survey is translated to Norwegian and tested for reliability and validity in a Norwegian population.

Sample size

The sample size calculation for the ETIP trial was based on difference between groups in the primary outcome; gestational weight gain from baseline assessments to delivery (see online supplementary file 1).32 35 Based on previous studies, a mean change of 6 kg was assumed as clinically relevant.52 53 A two-sided, independent samples t-test with 5% level of significance, SD of 10, and a power of 0.90 defined our target study population of 59 in each group. We estimated the dropout rate in the trial to be 15 %, and on basis of these estimations aimed to include 150 women. We have not performed a separate power calculation for the secondary analyses reported in this paper.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was performed after baseline assessments using a computer random number generator, developed and administrated at the Unit for Applied Clinical Research, NTNU. The personnel who provided the participants with questionnaires regarding psychological well-being in late pregnancy and postpartum were not blinded for group allocation. Further details about randomisation and blinding in the ETIP trial are published elsewhere.32

Statistical methods

We confirmed baseline data normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests and visual inspection of plots and histograms. Comparisons between groups at baseline were analysed by independent samples t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests. We analysed between-group differences in the effect of exercise training on psychological well-being (assessed by PGWBI) in late pregnancy and postpartum, and between-group difference in ‘Self-perceived general health status’ in late pregnancy by general linear model analysis of covariance. Changes within-groups from baseline to late pregnancy and from late pregnancy to postpartum were also analysed by general linear model analysis of covariance. Baseline values of each outcome were set as covariates in late pregnancy analyses, and late pregnancy values were set as covariates in postpartum analyses. We analysed differences between groups in EPDS using an independent samples t-test. We assessed differences in baseline PGWBI between the participants who exercised per protocol and the non-adherent participants in the exercise group by independent samples t-tests. Due to the randomisation model, we assumed no systematic differences between groups at baseline. We based our primary analyses on the ‘intention to treat’ principle and additionally performed ‘per protocol’ analyses, according to prespecified cut-off values for adherence to the exercise programme (see online supplementary file 1).35 No adjustment for multiple testing have been undertaken.

We used IBM SPSS Statistics V.23 and considered p values <0.05 as statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

No patients involved.

Results

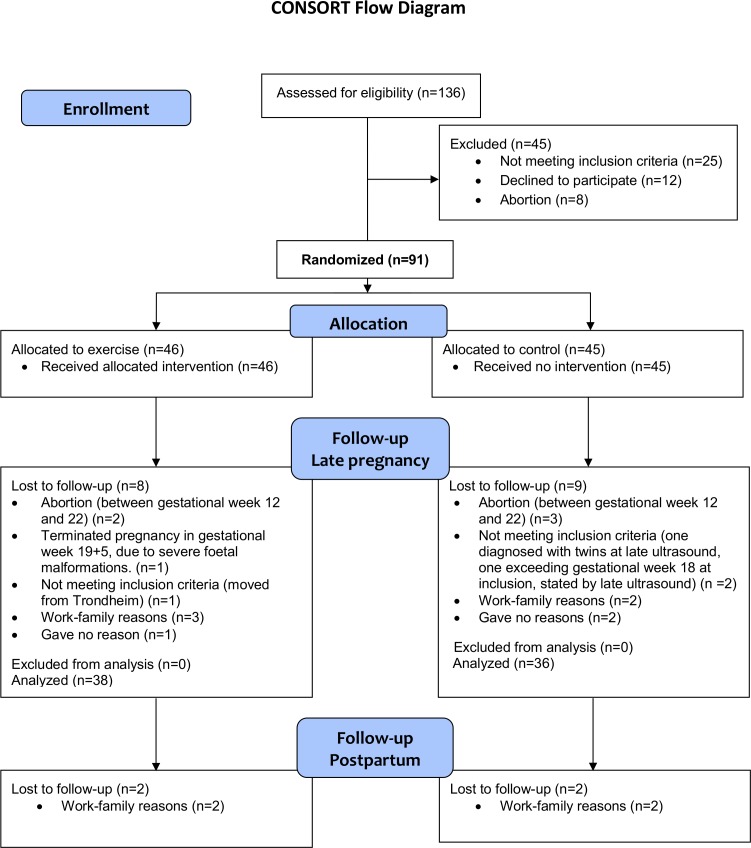

We assessed 136 women for eligibility and included 91 women, with 46 in the exercise group and 45 in the control group. Figure 1 shows the participant flow in the ETIP trial. The exercise group exercised 31.7±15.3 (range 0–53) sessions at the hospital and 19.2±16.5 (range 0–72) sessions at home, giving a weekly average of 1.30±0.8 supervised sessions and 0.8±0.7 home-based sessions. About 50% (n=19) of the women in the exercise group exercised according to our prespecified cut-off values for perprotocol analyses.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart ETIP trial. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; ETIP, exercise training in pregnancy.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups at baseline. Full trial baseline data have been published previously.32 At inclusion, 55% in the exercise group and 53% in the control group reported to fulfil the recommendations for physical activity (≥150 min/week of moderate intensity physical activity).

Table 1.

Subjects characteristics at baseline for the exercise and the control group. Observed data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), or number of participants with percentages. Psychological well-being is presented with the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) global score and six subscales

| Subjects characteristics | Exercise group (n=46) |

Control group (n=45) |

| Mean ± SD/N (%) | Mean ± SD/N (%) | |

| Age (years) | 31.3 ± 3.8 | 31.4 ± 4.7 |

| Body weight (kg) | 95.3 ± 12.8 | 98.3 ± 14.2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 33.9 ± 3.8 | 35.1 ± 4.6 |

| Weight classification | ||

| Overweight, BMI 28.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 3 (6.6) | 5 (11.1) |

| Class 1 obesity, BMI 30.0–34.9 kg/m2 | 28 (62.2) | 19 (42.2) |

| Class 2 obesity, BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m2 | 11 (24.4) | 15 (33.3) |

| Class 3 obesity, BMI≥40.0 kg/m2 | 3 (6.6) | 6 (13.3) |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 22 (47.8) | 19 (42.2) |

| 1 | 19 (41.3) | 19 (42.2) |

| 2 | 5 (10.9) | 4 (8.9) |

| ≥3 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.7) |

| Current smoking | 2 (4.7) | 4 (8.9) |

| Education | ||

| Primary/secondary school | 1 (2.3) | 3 (7.0) |

| High school | 15 (34.1) | 12 (27.9) |

| University ≤4 years | 14 (31.8) | 11 (25.6) |

| University >4 years | 14 (31.8) | 17 (39.5) |

| Currently employed | 38 (82.6) | 33 (73.3) |

| Self-perceived general health status | ||

| Very good | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.3) |

| Good | 25 (54.3) | 19 (49.4) |

| Either good or bad | 18 (39.1) | 20 (46.5) |

| Quite bad | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Bad | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) | 76.6 ± 11.1 | 76.2 ± 14.3 |

| Anxiety | 19.8 ± 3.3 | 19.2 ± 4.6 |

| Depressed mood | 13.2 ± 1.9 | 13.2 ± 1.9 |

| Positive well-being | 12.2 ± 2.8 | 12.6 ± 3.1 |

| Self-control | 12.9 ± 1.7 | 12.0 ± 2.5 |

| General health | 9.7 ± 2.8 | 9.5 ± 2.7 |

| Vitality | 8.8 ± 3.8 | 10.1 ± 3.4 |

Missing: education: control: 1. General health status: control: 3. PGWBI: exercise; 2. Control; 4. Statistics: baseline variables were analysed by independent samples t-test, and Fisher’s exact test.

BMI, body mass index.

In late pregnancy, 61% in the exercise group and 66% in the control group reported to adhere to the recommendations for physical activity, with corresponding numbers postpartum being 72% in the exercise group and 79% in the control group. In late pregnancy, 77% in the exercise group compared with 23% in the control group (p<0.01) reported regular exercise, with corresponding numbers postpartum being 46% in the exercise group and 25% in the control group (p=0.16). Approximately 58% of women in exercise group and 44% of women in the control group gained more weight during pregnancy than recommended by the Institute of Medicine (between-group difference, p=0.35).54

Psychological well-being in late pregnancy

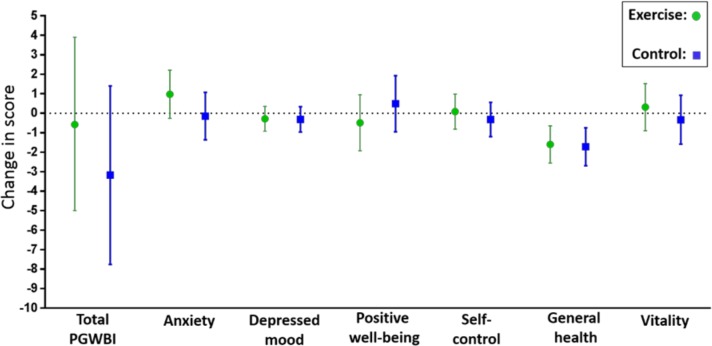

We did not find any statistically significant difference between the groups in PGWBI global score, nor in any of the six subscales, in late pregnancy (table 2). In the per protocol analyses in late pregnancy, PGWBI global score was 80.2 (95% CI 73.9 to 86.6) in participants who adhered to the exercise programme in the exercise group vs 74.7 (95% CI 70.4 to 79.0) in the control group (p=0.15) (see online supplementary table 1). There were no statistically significant between-group differences in the per protocol analyses, but a tendency of higher ‘Anxiety’ score in the perprotocol exercise group (21.4, 95% CI 19.7 to 23.2) compared with the control group (19.5, 95% CI 18.4 to 20.7) (p=0.07) (see online supplementary table 1). Figure 2 illustrates the changes in PGWBI global score and subscales from baseline to late pregnancy in each group.

Table 2.

Psychological general well-being (PGWBI) global score and subscales in late pregnancy and 3 months postpartum. ‘Intention to treat’ model-based analyses with comparisons between groups presented as estimated mean difference with 95% CIs and p values

| All participants | Exercise | Control | Difference between groups | ||||||||

| Late pregnancy | Postpartum | ||||||||||

| Score at baseline n=91 |

Score late pregnancy n=38 |

Score postpartum n=36 |

Score late pregnancy n=36 |

Score postpartum n=34 |

Diff | 95% CI | P value | Diff | 95% CI | P value | |

| PGWBI | 77.2 | 76.6 (72.2 to 81.0) | 85.4 (81.9 to 88.8) | 74.0 (69.4 to 78.5) | 84.6 (80.8 to 88.4) | 2.60 | −3.77 to 8.97 | 0.42 | 0.77 | −4.42 to 5.95 | 0.77 |

| Anxiety | 19.7 | 20.7 (19.5 to 22.0) | 20.6 (19.5 to 21.7) | 19.6 (18.4 to 20.8) | 21.8 (20.7 to 23.0) | 1.12 | −0.61 to 2.86 | 0.20 | −1.26 | −2.98 to 0.37 | 0.13 |

| Depressed mood | 13.4 | 13.2 (12.5 to 13.8) | 13.7 (13.2 to 14.1) | 13.1 (12.5 to 13.8) | 13.4 (12.9 to 13.9) | −0.03 | −0.88 to 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.25 | −0.43 to 0.93 | 0.47 |

| Positive well-being | 12.5 | 12.0 (11.0 to 13.0) | 13.9 (13.0 to 14.9) | 12.5 (11.5 to 13.5) | 13.6 (12.7 to 14.6) | −0.49 | −1.93 to 0.95 | 0.50 | 0.27 | −1.07 to 1.61 | 0.68 |

| Self-control | 12.5 | 12.6 (11.7 to 13.5) | 13.6 (13.0 to 14.1) | 12.2 (11.3 to 13.1) | 13.1 (12.5 to 13.7) | 0.40 | −0.87 to 1.67 | 0.53 | 0.44 | −0.38 to 1.25 | 0.29 |

| General health | 9.7 | 8.1 (7.1 to 9.0) | 11.5 (10.8 to 12.2) | 8.0 (7.0 to 8.9) | 11.2 (10.5 to 11.9) | 0.12 | −1.24 to 1.49 | 0.86 | 0.31 | −0.72 to 1.33 | 0.55 |

| Vitality | 9.5 | 9.8 (8.6 to 11.0) | 12.4 (11.3 to 13.4) | 9.2 (7.9 to 10.4) | 12.0 (10.9 to 13.1) | 0.65 | −1.15 to 2.44 | 0.47 | 0.38 | −1.18 to 1.94 | 0.63 |

Missing late pregnancy: exercise 8, control, 5. Missing postpartum: exercise 7, control 4. Statistics: general linear model analysis of covariance with baseline mean and late pregnancy mean as covariates.

PGWBI, Psychological General Well-Being Index.

Figure 2.

Changes in the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) global score and the six subscales from baseline to late pregnancy in the exercise group and the control group. Data are means with 95% CIs.

bmjopen-2018-028252supp002.pdf (62KB, pdf)

Self-perceived general health status in late pregnancy was reported to be Very good by 9% in the exercise group and 11% in the control group, Good by 53% in the exercise group and 29% in the control group, Either good or bad by 21% in the exercise group and 50%, Quite bad by 15% in the exercise group and 11% in the control group and Bad by 3% in the exercise group and none in the control group (between-group difference, p=0.37). Results were similar in the per protocol analyses (data not shown).

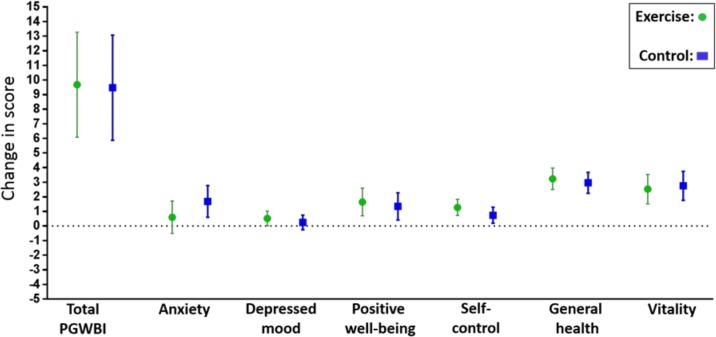

Psychological well-being 3 months postpartum

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in PGWBI global score, nor in any of the six subscales 3 months postpartum (table 2). In the postpartum per protocol analyses, PGWBI global score among women who adhered to the exercise programme in the exercise group was 84.8 (95% CI 79.5 to 90.2) versus 85.3 (95% CI 81.5 to 89.2) in the control group (p=0.88), with no statistically significant differences in any of the six subscales (see online supplementary table 1). Figure 3 illustrates the changes in PGWBI global score and subscales from late pregnancy to postpartum in each group.

Figure 3.

Changes in the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) global score and the six subscales from late pregnancy to postpartum in the exercise group and the control group. Data are means with 95% CIs.

Postnatal depression

We found no statistically significant difference in total EPSD score 3 months postpartum between the exercise group (2.96, 95% CI 1.7 to 4.2) and the control group (3.48, 95% CI 2.3 to 4.7) (p=0.55). None reported of a total EPSD score of 13 or more, representing indication of major depression. Two women (7.1%) in the exercise group and three women (10.3%) in the control group reported at total EPSD score between 10 and 12, representing indication of a minor depression. In the per protocol analysis, there was no statistical significant difference in total EPDS score between the exercise group (2.38, 95% CI 1.72 to 4.2) and the control group (3.48, 95% CI 2.3 to 4.7) (p=0.30).

Baseline comparison within the exercise group

Women in the exercise group who adhered to the intervention protocol reported a higher ‘Self-Control’ subscale score at baseline (13.5 vs 12.4, p=0.04) and a tendency of higher ‘Depressed mood score’ (13.8 vs 12.8, p=0.07), compared the non-adherent women in the exercise group.

Harms

We did not register any adverse events related to the intervention programme or the assessments in the ETIP trial. One woman in the control group reported a score indicating suicidal risk (EPDS). This participant got an immediate appointment with her general practitioner.

Discussion

Main findings

We found no statistically significant effects of offering supervised exercise training during pregnancy on psychological well-being in late pregnancy or 3 months postpartum, nor on symptoms of postnatal depression, among women with overweight or obesity. Both the exercise group and the control group reported good psychological well-being during pregnancy and postpartum and both groups had a low risk of postnatal depression. The psychological well-being was stable during pregnancy and increased significantly from late pregnancy to postpartum in both groups. The women in the exercise group who adhered to the exercise protocol were characterised by higher self-control and fewer symptoms of depression at baseline, compared with the non-adherent women in the exercise group. Only 50% of the women in the exercise group followed the exercise-protocol and we included less participants than estimated in the trial protocol.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The major strength of this study was the randomised controlled design. We assessed well-being by valid and reliable questionnaires.55 56 We included only women with prepregnancy overweight or obesity (BMI ≥28 kg/m2) in the trial, contributing to a homogenous study group. We recorded exercise adherence as well as self-reported physical activity levels throughout the trial period in both groups.

Limitations of the ETIP trial include a limited study sample, 20% dropout, and only 50% adherence to the exercise protocol.32 The low adherence to the exercise protocol may be explained by discomfort, by the women being anxious about getting exhausted, by having trouble with prioritising time for exercise and by lack of motivation for lifestyle changes.

These factors limit the chance of estimating a true effect of exercise training on psychological well-being. Furthermore, the relatively high level of physical activity in the control group could have reduced the chance of finding an effect of the intervention. Our trial included comprehensive health assessments and close monitoring of the women, regardless of group allocation. This close follow-up by health personnel may have prevented reduced psychological well-being among all the women in the trial. We had no information on previous mental health history or use of antidepressant treatment among the participants.

Comparison with other trials

Observational studies show that women who are physically active during pregnancy report better psychological well-being than less active women28 and that the risk of psychological health problems increases in parallel to decreased frequency of exercise during pregnancy.27 A limited number of RCTs have investigated the effects of exercise training on psychological well-being, and the results diverge.29 30 57 Bogaerts and colleagues30 showed reduced anxiety in late pregnancy among women with obesity who received an intervention combining regular motivational interviewing with advice about healthy eating and physical activity in pregnancy, compared with advice only or a standard care control group. They found no effect of the intervention on depression.30 In our study, the level of anxiety did not differ between groups in late pregnancy, but we observed a tendency of less symptoms of anxiety among the women who adhered to the exercise programme compared with the control group, which indicates a positive effect of regular exercise during pregnancy on the risk of anxiety. Gustafsson and coworkers29 investigated the effect of regular exercise during pregnancy on late pregnancy psychological well-being using PGWBI. They included women in all BMI categories, and found, similar to our trial, no effect of exercise on mental health. Also in their trial, the participants reported of good psychological well-being at baseline. This is in contrast to previous studies showing a high prevalence (15%–25%) of depression and anxiety among pregnant women with overweight/obesity2 7 8 58–61 and that especially the levels of anxiety increases from early to late pregnancy in this population.59 Compared with the general population of pregnant women with overweight/obesity, a higher percentage of women in the ETIP trial reported to fulfil the recommendations for physical activity during and after pregnancy,32 the number of pregnancy complications were lower, as was the percentage of women exceeding the Institute of Medicine guidelines for gestational weight gain.32 33 Low level of physical activity and exceeding the recommended gestational weight gain are both associated with increased risk for reduced psychological well-being, and these factors could therefore explain stabile PGWBI scores during pregnancy in our study group. Again, this indicates that we included women with good psychological well-being in our trial.

We found no effect of exercise training on the risk for postnatal depression, which is in line with previous studies suggesting limited effect of exercise interventions during pregnancy on risk for depression after delivery.31 57 Few of the participating women reported symptoms of postnatal depression in our trial. This is in contrast to a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting a high risk of developing depression during the postpartum period for women with prepregnancy obesity.1 Also a cohort study by Ertel and collegues,5 who assessed postnatal depression among 1686 women in all BMI categories, found that prepregnancy BMI >30 was associated with increased risk for depression 6 months postpartum. The EPDS records the woman’s self-perceived psychological well-being during the last week, and thereby the woman’s current state of anxiety and depression. On the other hand, the ‘State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)’ questionnaire, assesses both short-term and long-term symptoms and might provide a different set of information compared with the EPDS. Even though the EPDS is the most frequently used questionnaire for assessing risk for depression postpartum, the use of different questionnaires in comparative trials hampers comparison between studies.

Generalisability and clinical implications

When compared with women in the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry,62 the ETIP participants are representative for Norwegian pregnant women with overweight/obesity, according to BMI, obesity grades I, II, III, age, education, parity and occupational activity/employment.32 However, it is likely that women who volunteer for participation in an exercise trial are extra aware of possible benefits of maternal exercise, are more experienced with physical activity and suffer from less pregnancy complications. We believe that the findings of our study can be generalised to relatively healthy pregnant women with prepregnancy BMI of 28 or more.

We based the trial intervention programme on current recommendations for maternal exercise and designed it for easy implementation into clinical practice. Healthcare professionals, especially general practitioners and midwifes who consult pregnant women, are in a unique position to inform, help and guide women with high BMI throughout pregnancy. Distinct recommendations for exercise and physical activity should be given to all pregnant women, and the women should be closely monitored and motivated by maternal healthcare personnel throughout pregnancy. Assessing psychological well-being early in pregnancy may be important for prediction of adherence to exercise during pregnancy.

Conclusion

We found no statistically significant effects of supervised exercise training during pregnancy on psychological well-being in late pregnancy or postpartum, nor on the prevalence of symptoms of postnatal depression, among women with overweight or obesity. Both the exercise group and the control group reported good psychological well-being and low risk for postnatal depression. The level of self-control early in pregnancy may be important for exercise adherence during pregnancy. Low adherence to the exercise protocol in our trial could have reduced the chance of finding an effect of regular maternal exercise on mental health.

We need adequately powered trials, with good adherence to the intervention protocol, to be able to investigate the true effect of exercise during pregnancy on maternal well-being and to examine factors associated with motivation for exercise during pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @trinemoholdt

Contributors: KKG acquired the data, analysed the data, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. ASH interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. SM, SNS and KS designed the study and critically revised the manuscript. ØS provided the statistics in previous published papers in the ETIP trial, and reviewed statistical methods in the current manuscript. TM acquired some of the data, deigned the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority (RHA), grant number 46056728, and The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) grant number 7-370-00/08A supported this work. The participating women received infant food from Nestlé worth 500 Norwegian kroner.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data file are being available in Dryad, doi:10.5061/dryad.pvmcvdng6.

References

- 1. Molyneaux E, Poston L, Ashurst-Williams S, et al. . Obesity and mental disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:857–67. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nagl M, Linde K, Stepan H, et al. . Obesity and anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2015;186:293–305. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhu CS, Tan TC, Chen HY, et al. . Threatened miscarriage and depressive and anxiety symptoms among women and partners in early pregnancy. J Affect Disord 2018;237:1–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Catov JM, Abatemarco DJ, Markovic N, et al. . Anxiety and optimism associated with gestational age at birth and fetal growth. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:758–64. 10.1007/s10995-009-0513-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ertel KA, Huang T, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. . Perinatal weight and risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms. Ann Epidemiol 2017;27:695–700. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bliddal M, Pottegård A, Kirkegaard H, et al. . Mental disorders in motherhood according to prepregnancy BMI and pregnancy-related weight changes-A Danish cohort study. J Affect Disord 2015;183:322–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Faria-Schützer DB, Surita FG, Nascimento SL, et al. . Psychological issues facing obese pregnant women: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30:88–95. 10.3109/14767058.2016.1163543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Molyneaux E, Poston L, Ashurst-Williams S, et al. . Pre-pregnancy obesity and mental disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014;4:236 10.1016/j.preghy.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diener E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol 2000;55:34–43. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Medicine USNLo Postnatal depression. In: glossary pH, ED, 2018. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0024789/

- 11. Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, et al. . Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014;384:1800–19. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gentile S. Untreated depression during pregnancy: short- and long-term effects in offspring. A systematic review. Neuroscience 2017;342:154–66. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. . The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:e321–41. 10.4088/JCP.12r07968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2013;9:379–407. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis AJ, Austin E, Galbally M. Prenatal maternal mental health and fetal growth restriction: a systematic review. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2016;7:416–28. 10.1017/S2040174416000076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brunner S, Stecher L, Ziebarth S, et al. . Excessive gestational weight gain prior to glucose screening and the risk of gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2015;58:2229–37. 10.1007/s00125-015-3686-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nehring I, Schmoll S, Beyerlein A, et al. . Gestational weight gain and long-term postpartum weight retention: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1225–31. 10.3945/ajcn.111.015289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siega-Riz AM, Viswanathan M, Moos M-K, et al. . A systematic review of outcomes of maternal weight gain according to the Institute of medicine recommendations: birthweight, fetal growth, and postpartum weight retention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:339.e1–14. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baeten JM, Bukusi EA, Lambe M. Pregnancy complications and outcomes among overweight and obese nulliparous women. Am J Public Health 2001;91:436–40. 10.2105/ajph.91.3.436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin KE, Grivell RM, Yelland LN, et al. . The influence of maternal BMI and gestational diabetes on pregnancy outcome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015;108:508–13. 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Athukorala C, Rumbold AR, Willson KJ, et al. . The risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women who are overweight or obese. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:56 10.1186/1471-2393-10-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stanton R, Reaburn P. Exercise and the treatment of depression: a review of the exercise program variables. J Sci Med Sport 2014;17:177–82. 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, et al. . Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2016;202:67–86. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2005;18:189–93. 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. ACOG Committee opinion no. 650: physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e135–42. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sui Z, Dodd JM. Exercise in obese pregnant women: positive impacts and current perceptions. Int J Womens Health 2013;5:389–98. 10.2147/IJWH.S34042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watson SJ, Lewis AJ, Boyce P, et al. . Exercise frequency and maternal mental health: parallel process modelling across the perinatal period in an Australian pregnancy cohort. J Psychosom Res 2018;111:91–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Claesson I-M, Klein S, Sydsjö G, et al. . Physical activity and psychological well-being in obese pregnant and postpartum women attending a weight-gain restriction programme. Midwifery 2014;30:11–16. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gustafsson MK, Stafne SN, Romundstad PR, et al. . The effects of an exercise programme during pregnancy on health-related quality of life in pregnant women: a Norwegian randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2016;123:1152–60. 10.1111/1471-0528.13570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bogaerts AFL, Devlieger R, Nuyts E, et al. . Effects of lifestyle intervention in obese pregnant women on gestational weight gain and mental health: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes 2013;37:814–21. 10.1038/ijo.2012.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Songøygard KM, Stafne SN, Evensen KAI, et al. . Does exercise during pregnancy prevent postnatal depression? A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:62–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garnæs KK, Mørkved S, Salvesen Øyvind, et al. . Exercise training and weight gain in obese pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial (ETIP trial). PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002079 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Garnæs KK, Nyrnes SA, Salvesen Kjell Åsmund, et al. . Effect of supervised exercise training during pregnancy on neonatal and maternal outcomes among overweight and obese women. secondary analyses of the ETIP trial: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173937 10.1371/journal.pone.0173937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garnæs KK, Mørkved S, Salvesen Kjell Å, et al. . Exercise training during pregnancy reduces circulating insulin levels in overweight/obese women postpartum: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial (the ETIP trial). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:18 10.1186/s12884-017-1653-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moholdt TT, Salvesen K, Ingul CB, et al. . Exercise training in pregnancy for obese women (ETIP): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2011;12:154 10.1186/1745-6215-12-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. World Health Organization W Obesity and overweight 2015.

- 37. Helsedirektoratet Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for svangerskapsomsorgen. In: Helsedirektoratet, ed. IS-1179. Available: https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/nasjonal-faglig-retningslinje-for-svangerskapsomsorgen2005

- 38. Artal R, O'Toole M. Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:6–12. 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. ACOG Committee Obstetric Practice ACOG Committee opinion. number 267, January 2002: exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:171–3. 10.1097/00006250-200201000-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Health TNDo 2015.

- 41. Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CD, et al. . Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. Am J Cardiol 1984;54:908–13. 10.1016/S0002-9149(84)80232-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. HJ. D The Psychological general Well-Being (PGWB) Index. In: Assessment of Quality of Life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies In: Wenger NK MM, Furberg CD, Elinson J, et al., eds Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies, 1984: 170–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Naughton MJ, Wiklund I. A critical review of dimension-specific measures of health-related quality of life in cross-cultural research. Qual Life Res 1993;2:397–432. 10.1007/BF00422216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lundgren-Nilsson Åsa, Jonsdottir IH, Ahlborg G, et al. . Construct validity of the psychological General well being index (PGWBI) in a sample of patients undergoing treatment for stress-related exhaustion: a Rasch analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:2 10.1186/1477-7525-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gaston JE, Vogl L. Psychometric properties of the general well-being index. Qual Life Res 2005;14:71–5. 10.1007/s11136-004-0793-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wiklund I, Karlberg J. Evaluation of quality of life in clinical trials. Selecting quality-of-life measures. Control Clin Trials 1991;12:204s–16. 10.1016/s0197-2456(05)80024-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Helvik A-S, Jacobsen G, Hallberg LR-M. Psychological well-being of adults with acquired hearing impairment. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:535–45. 10.1080/09638280500215891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–6. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cox J. Use and misuse of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): a ten point 'survival analysis'. Arch Womens Ment Health 2017;20:789–90. 10.1007/s00737-017-0789-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, et al. . The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale: validation in a Norwegian community sample. Nord J Psychiatry 2001;55:113–7. 10.1080/08039480151108525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Berle J Ø, Aarre TF, Mykletun A, et al. . Screening for postnatal depression. Validation of the Norwegian version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, and assessment of risk factors for postnatal depression. J Affect Disord 2003;76:151–6. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00082-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Christiansen T, Paulsen SK, Bruun JM, et al. . Exercise training versus diet-induced weight-loss on metabolic risk factors and inflammatory markers in obese subjects: a 12-week randomized intervention study. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010;298:E824–31. 10.1152/ajpendo.00574.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wolff S, Legarth J, Vangsgaard K, et al. . A randomized trial of the effects of dietary counseling on gestational weight gain and glucose metabolism in obese pregnant women. Int J Obes 2008;32:495–501. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rasmussen KM, Abrams B, Bodnar LM, et al. . Recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy in the context of the obesity epidemic. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1191–5. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60da7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grossi E, Groth N, Mosconi P, et al. . Development and validation of the short version of the psychological General well-being index (PGWB-S). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:88 10.1186/1477-7525-4-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Toreki A, Andó B, Dudas RB, et al. . Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a screening tool for postpartum depression in a clinical sample in Hungary. Midwifery 2014;30:911–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dodd JM, Newman A, Moran LJ, et al. . The effect of antenatal dietary and lifestyle advice for women who are overweight or obese on emotional well-being: the limit randomized trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:309–18. 10.1111/aogs.12832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Andersson L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, et al. . Point prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the second trimester of pregnancy: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:148–54. 10.1067/mob.2003.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bogaerts AFL, Devlieger R, Nuyts E, et al. . Anxiety and depressed mood in obese pregnant women: a prospective controlled cohort study. Obes Facts 2013;6:152–64. 10.1159/000346315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bogaerts A, Devlieger R, Van den Bergh BRH, et al. . Obesity and pregnancy, an epidemiological and intervention study from a psychosocial perspective. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2014;6:81–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marchi J, Berg M, Dencker A, et al. . Risks associated with obesity in pregnancy, for the mother and baby: a systematic review of reviews. Obes Rev 2015;16:621–38. 10.1111/obr.12288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Medisinsk fødselsregister og abortregisteret - statistikkbanker [press release], 2015. Folkehelseinstituttet. Available: http://statistikkbank.fhi.no/mfr/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028252supp001.pdf (270.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028252supp002.pdf (62KB, pdf)