Abstract

Objectives

Previous hospital-based studies have suggested delayed recognition of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in women. We wanted to assess differences in symptom presentation or triage among women and men who contacted primary care out-of-hours services (OHS) for chest discomfort.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

Primary care OHS.

Participants

276 women and 242 men with chest discomfort who contacted a primary care OHS in the Netherlands in 2013 and 2014.

Main outcome measures

Differences between women and men regarding symptom presentation and urgency allocation.

Results

8.4% women and 14.0% men had ACS. Differences in symptoms between patients with and without ACS were in general small, for both women and men. In women with ACS compared with women without ACS, mean duration of telephone calls was discriminative; 5.22 (SD 2.53) vs 7.26 (SD 3.11) min, p value=0.003. In men, radiation of pain (89.3% vs 54.9%, p value=0.011) was discriminative for ACS, and stabbing chest pain (3.7% vs 24.0%, p value=0.014) for absence of ACS. Women and men with chest discomfort received similar high urgency allocation (crude and adjusted OR after correction for ACS and age; 1.03 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.48) and 1.04 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.52), respectively). Women with ACS received a high urgency allocation in 22/23 (95.7%) and men with ACS in 30/34 (88.2%), p value=0.331.

Conclusions

Discriminating ACS in patients with chest discomfort who contacted primary care OHS is difficult in both women and men. Women and men with chest discomfort received similar high urgency allocation.

Keywords: gender, primary care out-of-hours service, chest pain, acute coronary syndrome, triage

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We could evaluate the initial symptom presentation of women and men with chest discomfort before knowledge of the eventual diagnosis, thus without hindsight bias.

We assessed routine care data and thus could analyse only a restricted number of determinants.

37.7% of cases could not be included as participants, since we did not receive information from the patients’ general practitioner to make a diagnosis. This did not seem to bias our results because patient characteristics were similar between participants and non-participants.

Only a small number of patients with chest discomfort actually had an acute coronary syndrome; therefore, no firm conclusions on disparities on symptom presentation between women and men can be made.

Relatively small numbers and missing data prevented us from full multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Introduction

In the Netherlands, patients in general first present to primary care and the general practitioner (GP) decides as a ‘gatekeeper’ who should be sent to a hospital for further analysis. Chest discomfort, however, is an exception with 80% first contacting the GP and 20% directly calling the ambulance or appearing as self-referrals.1 Chest discomfort is a common reason for contacting primary care and around 10%–15% has an underlying cardiac cause, most often coronary artery disease (CAD), including an acute coronary syndrome (ACS).1–3 Timely diagnosis of an ACS is of utmost importance, because early medical and interventional treatment can save myocardium (‘time is muscle’) and lives.4

Previous hospital-based studies described a delayed recognition of ACS in women compared with men.5–8 This delayed recognition of ACS in women has been related to an atypical presentation in women.9–11 Previous studies also identified that management of chest discomfort by physicians may be influenced by gender of the patient caused by an underestimation of the risk of CAD in women.12 13 However, this information is selectively retrieved in those with an established ACS diagnosis and seen at the emergency department for chest pain. Importantly, however, during the diagnostic assessment, the clinician is interested in patient characteristics that help to discriminate women with ACS from women without, and similarly for men. Notably in primary care, where ECG and fast results of high-sensitive troponin levels are lacking.

We assessed the triage of women and men presenting with chest discomfort to a primary care out-of-hours service (OHS) to answer the following question: Are there gender disparities in symptom presentation or triage in patients presenting with chest discomfort to a primary OHS?

Methods

Primary care OHS

In the Netherlands, primary care OHS covers primary care in 73% of the hours of the week. The first contact of a patient to a primary care OHS is by telephone, and trained triage nurses who are supervised by a GP initially handle these calls. Most Dutch OHS use the ‘Netherlands Triage Standard’ (NTS) to triage patients. The NTS started in November 2012 as a decision aid for triage nurses to classify the urgency of the complaint. Based on the initial symptom of the patient, the triage nurse chooses within the NTS system the most appropriate module among 56 NTS modules based on clinical symptoms, and ‘chest discomfort’ is one of them.14 Based on a decision tree with several hierarchically ordered questions (triage criteria), specified for each module, the NTS generates one out of five urgency levels (U1–U5, online supplementary appendix table 1). In case of a potential life-threatening situation (U1), an ambulance and/or the GP should arrive at the patient’s location within 15 min. U2 means that the patient should be evaluated within 1 hour and in case of U3, the patient should be assessed within 3 hours. If considered not urgent, the patient should be seen the same day (U4), unless a telephone advice is sufficient (U5). The triage nurse, but also the GP on duty can overrule the assigned computer-based urgency if considered necessary. The routing through each decision tree is the same for women and men. In the module ‘chest discomfort’ (1) severe pain (≥7 on a scale from zero to 10), (2) radiation of chest pain to arm or neck, (3) experiencing accompanying shortness of breath or (4) symptoms related to activation of the sympathetic nervous system such as sweating, nausea/vomiting, pale face an/or (near) fainting will result in the highest urgency level (U1). The NTS has, however, never been formally validated by correlating the generated urgencies to clinical endpoints.14

bmjopen-2019-031613supp001.pdf (87.4KB, pdf)

Study population

This study was carried out in primary care OHS ‘de Gelderse Vallei’ in Ede, the Netherlands. Since 2001, in total 120 GPs provide primary care to a population of around 270 000 people. For the current analysis we used consecutive back-up tapes of telephone contacts classified in the NTS as ‘chest discomfort’ in the months November and December 2013, and January, May, June and July 2014. We chose these two sets of three consecutive months to be able to neutralise seasonal effects. We excluded young adults below the age of 30, repeated contacts, contacts that could not be retrieved from the back-up system and patients without definitive diagnosis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or planning of the study.

Data collection

Age, gender, date, time of the telephone contact, presented symptoms and the allocated urgency level were extracted from the electronic ‘call management system’. In some instances, there was a link between the digital record of the GP of the patient and the OHS, and the medical history and drug use of the patient were available during the call. The original telephone calls were retrieved from ‘Freedom Call Manager’, a back-up system containing all telephone calls with the primary care OHS. Research students replayed the telephone calls (MS, EV, AB) and scored them on a standardised case record form (online supplementary appendix table 2). With the case record form clinical items were registered, such as symptoms, pain characteristics, medical history and the duration of the call. We used the real life telephone calls as source of data giving us the opportunity to evaluate the very initial, ‘unbiased’ presentation of the patients. As a consequence, we could only analyse information that was discussed during the telephone call.

Medical diagnosis

To retrieve the medical diagnosis related to the primary care OHS contact, we contacted the patient’s own GP. They were asked to fill out a case record form with questions about the final medical diagnosis. If this was an ACS, they were asked to classify it in (1) ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), (2) non-STEMI or (3) unstable angina pectoris, based on the discharge letter of the hospital admission related to the OHS contact.

Data analysis

Data were stratified by sex. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (SD), and the duration of the telephone calls as mean (SD). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentage). Differences between sexes were assessed with the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The five urgency levels were dichotomised in high urgency (U1-2) and low urgency (U3-5) before analysis. We analysed differences in characteristics between participants and patients in whom the medical diagnosis could not be retrieved, to exclude selection bias (online supplementary appendix table 3). We used both univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis with urgency allocation (high vs low) as the outcome to assess differences between women and men with chest discomfort. For multivariable analysis, after adjustment for the diagnosis ACS and age. Results were expressed as OR with a 95% CI. The retrieved medical diagnoses were categorised. We combined rhythm disorders, heart failure, pericarditis, symptoms related to very high blood pressure and stable angina pectoris in ‘other cardiovascular diseases’. All data analyses were performed with IBM SPSS V.25.0 for Windows.

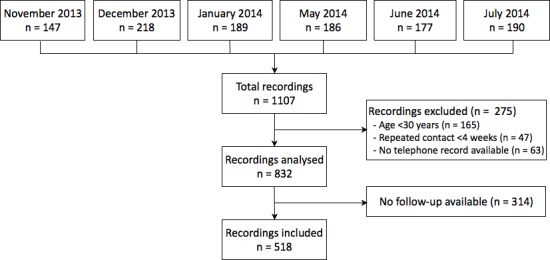

Results

A flow chart of the study population is presented in figure 1. In 518 patients, the medical diagnosis could be retrieved; there were 242 men (46.7%) and 276 women (53.3%) of whom 22 (8.4%) women and 34 (14.0%) men had an ACS. There were no differences in sex, age, duration of the telephone calls and urgency allocation between participants and patients in whom the medical diagnosis could not be retrieved.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population.

An overview of the baseline characteristics and symptoms of the participants is given in table 1. In women with an ACS compared with those without an ACS, the duration of the telephone calls was less long (5.22 (SD 2.53) vs 7.26 (SD 3.11) min, p value=0.003). In men this difference was non-significant (6.27 (SD 2.59) vs 7.22 (SD 2.51) min, p value=0.087). In both sexes, patients with ACS experienced a pressing chest pain more often than those without ACS. A stabbing pain was less frequent in men with ACS than in those without ACS; 3.7% vs 24.0%, p value=0.014. None of the women and men with ACS experienced right-sided chest pain. Men with ACS more often expressed radiation of pain than patients without ACS (men 89.3% vs 64.9%, p value=0.011). Shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting and sweating were similarly distributed among those with and without ACS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 276 women and 242 men with and without ACS contacting the primary care OHS for chest discomfort

| Women (n=276) | Men (n=242) | |||||

| ACS n=23 (8.3%) |

No ACS n=253 (91.7%) |

P value | ACS n=34 (14.0%) | No ACS n=208 (86.0%) | P value | |

| Mean duration of call, min (SD) | 5.22 (2.53) | 7.26 (3.11) | 0.003 | 6.27 (2.59) | 7.22 (2.51) | 0.087 |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 66.8 (18.0) | 62.8 (15.9) | 0.309 | 68.1 (14.2) | 58.8 (16.1) | 0.224 |

| History of CVD (n=210) | 15 (71.4%) | 94 (50.3%) | 0.066 | 21 (65.6%) | 80 (50.3%) | 0.113 |

| Chest pain (n=455) | 22 (95.7%) | 215 (87.0%) | 0.228 | 34 (100%) | 184 (91.1%) | 0.070 |

| Type of chest pain | ||||||

| Pressing (n=249) | 15 (78.9%) | 131 (58.7%) | 0.084 | 18 (64.3%) | 85 (46.4%) | 0.079 |

| Stabbing (n=90) | 3 (15.8%) | 42 (18.8%) | 0.743 | 1 (3.7%) | 44 (24.0%) | 0.014 |

| Pain location | ||||||

| Left side of the chest (n=107) | 4 (36.4%) | 44 (23.8%) | 0.346 | 7 (46.7%) | 52 (33.1%) | 0.291 |

| Right side of the chest (n=32) | 0 (0%) | 13 (7.0%) | 0.363 | 0 (0%) | 19 (12.1%) | 0.153 |

| Mid-sternal (n=143) | 7 (63.6%) | 78 (42.2%) | 0.163 | 7 (46.7%) | 51 (32.5%) | 0.267 |

| Radiation of the pain to | ||||||

| Arm (n=154) | 9 (60.0%) | 78 (42.4%) | 0.186 | 17 (63.0%) | 50 (33.3%) | 0.003 |

| Back or shoulder (n=124) | 8 (66.7%) | 73 (51.8%) | 0.321 | 6 (46.2%) | 37 (37.0%) | 0.523 |

| Jaw (n=44) | 2 (18.2%) | 25 (17.6%) | 0.961 | 5 (29.4%) | 12 (10.7%) | 0.034 |

| Any radiation (n=295) | 18 (90.0%) | 154 (78.6%) | 0.227 | 25 (89.3%) | 98 (64.9%) | 0.011 |

| Additional symptoms | ||||||

| Dyspnoea (n=219) | 9 (69.2%) | 110 (63.2%) | 0.664 | 10 (47.6%) | 90 (61.6%) | 0.220 |

| Nausea or vomiting (n=141) | 5 (45.5%) | 75 (39.5%) | 0.694 | 11 (42.3%) | 50 (35.2%) | 0.489 |

| Sweating (n=166) | 10 (52.6%) | 72 (35.5%) | 0.138 | 17 (60.7%) | 67 (43.5%) | 0.093 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CVD, cardiovascular disease; n, number of patients; OHS, out-of-hours services.

Triage

Both women and men with chest discomfort more often received a high urgency allocation (U1, U2) (women 65.6% vs men 64.9%). Also in those with an ACS, women and men received as often a high urgency allocation (95.7% vs 88.2%, p value=0.331, table 2). Men and women with ACS more often received a high urgency allocation than those who showed not to have an ACS (crude OR 6.36, 95% CI 2.49 to 16.24). Urgency allocation between women and men remained the same after adjustment for ACS and age (crude OR 1.03 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.48) and adjusted OR 1.04 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.52, table 3).

Table 2.

Urgency allocation in women and men with chest discomfort, and selectively in those with ACS

| High urgency (n=338) | Low urgency (n=180) | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| All patients with chest discomfort (n=518) | ||||

| Women (%) | 181 (65.6) | 95 (34.4) | 1.03 (0.72 to 1.48) | 0.867 |

| Men (%) | 157 (64.3) | 85 (35.1) | ||

| Patients with ACS diagnosis (n=57) | High urgency (n=52) | Low urgency (n=5) | ||

| Women (%) | 22 (95.7) | 1 (4.3) | 2.93 (0.31 to 28.09) | 0.331 |

| Men (%) | 30 (88.2) | 4 (11.8) |

High urgency: U1 or U2; low urgency: U3 or U4 or U5.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted ORs of women versus men for urgency allocation in 518 persons with chest discomfort

| High vs low urgency Crude OR (95% CI) |

|

| Women vs men | 1.03 (0.72 to 1.48) |

| ACS vs no ACS | 6.36 (2.49 to 16.24) |

| Age per year | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) |

|

High

vs

low urgency

Adjusted OR ( 95% CI ) |

|

| Women vs men adjusted for ACS | 1.11 (0.77 to 1.61) |

| Women vs men adjusted for ACS and age | 1.04 (0.72 to 1.52) |

High urgency: U1 or U2, low urgency: U3 or U4 or U5.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

Medical diagnosis

Men more often had an ACS than women (14.0% vs 8.4%, p value=0.038). The distribution of unstable angina, non-STEMI, STEMI and ‘non-classified myocardial infarction’ are presented in table 4. Men had more often ‘non-classified myocardial infarction’ (26.5% vs 8.9%). Musculoskeletal pain was the most common diagnosis in both sexes (35.9% vs 40.5%). All other diagnoses were equally distributed among men and women (table 4).

Table 4.

Diagnosis of 518 patients who contacted the OHS for chest discomfort, divided in women and men

| Women n=276 (%) | Men n=242 (%) | P value | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 23 (8.4) | 34 (14.0) | 0.038 |

| UAP | 8 (34.8) | 12 (35.3) | |

| NSTEMI | 10 (43.5) | 7 (20.6) | |

| STEMI | 3 (13.0) | 6 (17.6) | |

| Non-classified myocardial infarction* | 2 (8.7) | 9 (26.5) | |

| Other cardiovascular diseases† | 35 (12.7) | 30 (12.4) | 0.922 |

| Gastrointestinal tract disorders | 38 (13.8) | 23 (9.5) | 0.133 |

| Respiratory tract disorders | 37 (13.4) | 34 (14.0) | 0.832 |

| Psychogenic disorders | 25 (9.1) | 12 (5.0) | 0.071 |

| Non-specific chest pain including musculoskeletal pain | 99 (35.9) | 98 (40.5) | 0.279 |

| Other diagnoses | 19 (6.9) | 11 (4.5) | 0.256 |

*No further information whether it was a STEMI or NSTEMI.

†Including rhythm disorders, heart failure, pericarditis, symptoms related to very high blood pressure and stable angina pectoris.

NSTEMI, Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction;OHS, out-of-hours services; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

Discussion

In both women and men, it is very difficult to differentiate those with ACS from those without in patients with chest discomfort who contact the primary care OHS. In men, stabbing chest pain was significantly more often present in non-ACS patients (2.9% vs 21.1%, p value=0.014), while radiation of pain was significantly more often mentioned by men with ACS (73.5% vs 47.1%, p value-0.011). ‘Classical’ symptoms of ACS (oppressing chest pain, with radiation and sweating) were more common in both women and men with ACS as compared with women and men without ACS. Women were not undertriaged, and those with ACS received at least as high urgency allocations as men. Interestingly, women with an ACS had significant shorter telephone call duration than women without an ACS (5.22 vs 7.26 min, p value=0.003), while in men this difference was smaller and not significant (6.27 vs 7.22 min, p value=0.087), suggesting that triage nurses were able to recognise an ACS earlier in women than in men. We were unable to adequately assess the predictive value of symptoms in women and men separately with multivariable logistic regression analysis, because of a limited number of events (23 (8.3%) women and 34 (14.0%) men had an ACS).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that included the medical diagnosis in the evaluation of triage of patients with chest discomfort who contacted primary care. One Norwegian study showed that 50% of patients who contacted the primary care OHS for chest pain were referred to the hospital, however a final medical diagnosis was lacking.15 Another study from the Netherlands assessed gender differences in the symptom presentation of patients suspected of an ACS in primary care (from both day care and out-of hours) found no relevant differences between sexes regarding chest pain and autonomic nervous system-associated symptoms, but information on other symptoms or urgency allocation is lacking.16 They did find, however, a significant longer doctor delay in women than in men with chest discomfort: 45 min vs 33 min (p value=0.01).16 Our results on the prevalence of ACS in women (8.3%) and men (14.0%) is in line with a previous study performed in German primary care reporting a prevalence of 14% in women and 17% in men in those with acute chest pain.17

Multiple previous studies compared symptoms of women and men with ACS, and only one single study compared symptoms similarly as we did; comparing women with and without ACS, and men with and without ACS. In this study, executed among 736 patients seen in four emergency departments, the authors concluded that there were more similarities than differences in symptom predictors of ACS for women and men.18 As said, most studies performed at the emergency department compared men and women with ACS, and concluded that women were more likely to present with dyspnoea instead of chest pain, and with atypical symptoms (eg, nausea/vomiting, indigestion and palpitations) compared with men.19 20 This is different to our results, showing no clear difference in symptoms between women and men with ACS. But even more importantly, from the practising clinician point of view it is not relevant to know if women and men with ACS differ from each other in symptom presentation, the clinician wants to know which symptoms or other patient characteristics help to differentiate (1) women with ACS from women without, and (2) men with ACS from men without. This is even more relevant for primary care, where the GP needs to decide whom to refer and with what urgency, all based on clinical items and very limited access to timely ECG and results of high-sensitive troponin.

Our study has several strengths. First, we had the opportunity to evaluate the very initial symptom presentation of women and men with chest discomfort. This is important, since the presentation may change over time when multiple healthcare workers repeatedly ask comparable questions. Second, by replaying the telephone calls we were not hampered by recall bias of patients. Third, we used data from a primary care OHS that provides out-of-hours primary care services during 73% of the week-hours for 270 000 people, including rural and city areas, making the study population a good representation of everyday patients seen in primary care.

A limitation of the study was that we were not able to retrieve the medical diagnosis in all 832, but only in 518 (62.3%) patients. This was because some GPs did not provide follow-up data, mainly because they were afraid of violation of the privacy of the patient. Selection bias is, however, unlikely because the missing medical diagnoses were not patient driven. Moreover, comparison of the 518 participants with follow-up data and the 314 without a final diagnosis did not show significant differences in important determinants such as age, sex, duration of telephone calls, symptoms and urgency allocation. A second limitation is that we could not present data of patients who immediately called an ambulance or went on their own to an emergency department which is around 20% of those experiencing chest discomfort in the Netherlands.1 A third limitation was missing data on some determinants which is rather common in an observational study with real life data. Fourth, a relatively low number of symptoms could univariably be analysed because the NTS restricts the number of questions to patients with the aim not to lose too much time with the telephone triage. Since this is not part of the NTS, risk factors for ischaemic heart disease and co morbidities could not be evaluated. Fifth, missing values on symptoms prevented us from full multivariable analysis with urgency allocation (high vs low) as the outcome, and the low number of ACS cases let us decide to refrain from multivariable logistic regression analysis comparing symptoms with ACS (yes/no) as the outcome ACS. Moreover, the low number of patients with ACS did lead to large CIs of ORs in the logistic regression analysis. Finally, we do not know whether men and women differ in patient’s delay, as we have not assessed the durations of symptoms until calling the primary care-OHS.

Conclusion

Discriminating patients with ACS from those without in patients with chest discomfort who contacted primary care OHS seems equally difficult for women and men. Women and men with chest discomfort received similar high urgency allocation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the triagists and GP’s of primary care OHS 'de Gelderse Vallei' in Ede, particularly Kien Smulders and Astrid Bos for giving us the opportunity to perform this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: FHR and YvdG. Data collection: MvdM, MS, EV and AB. Analysis and interpretation: MvdM, YA, KR, YvdG, HMN, FHR. First draft MvdM and KR. Revising work: MvdM, YA, KR, YvdG, HMN, PD, MS, EV, AB and FHR.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht and the advisory board of General Practitioners Committee 'De Gelderse Vallei' approved the study protocol. The study was carried out according tot the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and de-identified patient data were used for analysis. ID of the approval: 13-206/C.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Mol KA, Smoczynska A, Rahel BM, et al. Non-cardiac chest pain: prognosis and secondary healthcare utilisation. Open Heart 2018;5:e000859 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buntinx F, Knockaert D, Bruyninckx R, et al. Chest pain in general practice or in the hospital emergency department: is it the same? Fam Pract 2001;18:586–9. 10.1093/fampra/18.6.586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoorweg BB, Willemsen RT, Cleef LE, et al. Frequency of chest pain in primary care, diagnostic tests performed and final diagnoses. Heart 2017;103:1727–32. 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Keefe-McCarthy S. Women's experiences of cardiac pain: a review of the literature. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs 2008;18:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lefler LL, Bondy KN. Womenʼs delay in seeking treatment with myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;19:251–68. 10.1097/00005082-200407000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sullivan AL, Beshansky JR, Ruthazer R, et al. Factors associated with longer time to treatment for patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes: a cohort study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:86–94. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jakobsen L, Niemann T, Thorsgaard N, et al. Sex- and age-related differences in clinical outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention 2012;8:904–11. 10.4244/EIJV8I8A139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brieger D, Eagle KA, Goodman SG, et al. Acute coronary syndromes without chest pain, an underdiagnosed and undertreated high-risk group. Chest 2004;126:461–9. 10.1378/chest.126.2.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain. JAMA 2000;283:3223–9. 10.1001/jama.283.24.3223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bösner S, Haasenritter J, Hani MA, et al. Gender bias revisited: new insights on the differential management of chest pain. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:1–8. 10.1186/1471-2296-12-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation 2005;111:499–510. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poon S, Goodman SG, Yan RT, et al. Bridging the gender gap: insights from a contemporary analysis of sex-related differences in the treatment and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2012;163:66–73. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Ierland Y, van Veen M, Huibers L, et al. Validity of telephone and physical triage in emergency care: the Netherlands triage system. Fam Pract 2011;28:334–41. 10.1093/fampra/cmq097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burman RA, Zakariassen E, Hunskaar S. Management of chest pain: a prospective study from Norwegian out-of-hours primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:51–8. 10.1186/1471-2296-15-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bruins Slot MHE, Rutten FH, van der Heijden GJMG, et al. Gender differences in pre-hospital time delay and symptom presentation in patients suspected of acute coronary syndrome in primary care. Fam Pract 2012;29:332–7. 10.1093/fampra/cmr089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bösner S, Haasenritter J, Hani MA, et al. Gender differences in presentation and diagnosis of chest pain in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:79–87. 10.1186/1471-2296-10-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeVon HA, Rosenfeld A, Steffen AD, et al. Sensitivity, specificity, and sex differences in symptoms reported on the 13‐Item acute coronary syndrome checklist. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:1–9. 10.1161/JAHA.113.000586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Milner KA, Funk M, Richards S, et al. Gender differences in symptom presentation associated with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1999;84:396–9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00322-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zucker DR, Griffith JL, Beshansky JR, et al. Presentations of acute myocardial infarction in men and women. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:79–87. 10.1007/s11606-006-5001-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031613supp001.pdf (87.4KB, pdf)