Abstract

Aims

There has been a paradigm shift proposing that comorbidities are a major contributor towards the heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) syndrome. Furthermore, HFpEF patients have abnormal macrovascular and microvascular function, which may significantly contribute towards altered ventricular-vascular coupling in these patients. The IDENTIFY-HF study will investigate whether gradually increased arterial stiffness (in addition to ageing) as a result of increasing common comorbidities, such as hypertension and diabetes, is associated with HFpEF.

Methods and analysis

In our observational study, arterial compliance and microvascular function will be assessed in five groups (Groups A to E) of age, sex and body mass index matched subjects (age ≥70 years in all groups):

Group A; normal healthy volunteers without major comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus (control). Group B; patients with hypertension without diabetes mellitus or heart failure (HF). Group C; patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus without HF. Group D; patients with HFpEF. Group E; patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (parallel group). Vascular function and arterial compliance will be assessed using pulse wave velocity, as the primary outcome measure. Further outcome measures include cutaneous laser Doppler flowmetry as a measure of endothelial function, transthoracic echocardiography and exercise tolerance measures. Biomarkers include NT-proBNP, high-sensitivity troponin T, as well as serum galectin-3 as a marker of fibrosis.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the regional research ethics committee (REC), West Midland and Black Country 17/WM/0039, UK, and permission to conduct the study in the hospital was also obtained from the RDI, UHCW NHS Trust. The results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented in local, national and international medical society meetings.

Trial registration number

Keywords: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, comorbidities, pathophysiology, arterial stiffness

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An important observational study aimed towards the understanding of the complex pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Will provide insight whether the HFpEF syndrome is associated with increased arterial stiffness, as a result of increasing comorbidities on top of ageing.

Comprehensive study of patients with increasing comorbidities investigating macrovascular/microvascular function, echocardiographic/biochemical aspects and endothelial function in age, sex and body mass index-matched groups.

A limitation of the study is that groups with more combinedcomorbidities (eg, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and chronic kidney disease) should have been included to fully investigate the potential effect of increasing comorbidities on arterial stiffness, which might then lead to HFpEF. Further, the cross-sectional design of the study has related disadvantages.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a major growing public health concern with approximately 20 million patients affected globally, posing a significant health economic burden, with an estimated cost of $108 billion per year worldwide.1 In the UK alone, approximately 5% of all emergency medical admissions are due to heart failure with an approximate cost to the National Health Service of £1.9 billion per year.2 Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is reported to comprise about 50% of the total heart failure burden and continues to have a high and unchanged mortality over many years, a poor quality of life and similar readmission rates to heart failure and reduced ejectionfraction (HFrEF).3 4 The prognosis of HFpEF is comparable to systolic heart failure, now referred to as HFrEF, with an estimated 5-year mortality of around 50%. This is worrying as no treatments that influence outcome in HFpEF have so far been found.5 Most large-scale pharmacological phase III clinical trials have been unsuccessful.6 7 While there is no single reason contributing to the negative result of these trials, the most likely explanation is that our understanding of the pathophysiology of the HFpEF syndrome remains incomplete and we are, therefore, currently unable to produce therapies targeted at the underlying mechanisms causing the syndrome.8 Therefore, in order to develop evidence-based treatments in patients with HFpEF, the underlying diverse pathophysiology requires further investigation.

Recently, there has been a shift in paradigm whereby comorbidities are thought to contribute significantly to HFpEF syndrome.9 Furthermore, current evidence strongly suggests that HFpEF patients have abnormal macrovascular and microvascular function with abnormal ventricular-vascular coupling.10 However, the effect of comorbidities on arterial stiffness and the HFpEF syndrome remains incompletely understood.

This study aims to investigate the pathophysiological process of HFpEF and this understanding will promote further research, aiding the development of new evidence-based interventions and/or early prevention strategies.

Hypothesis

HFpEF is a complex syndrome which is characterised by signs and symptoms of heart failure and a normal or a close to normal ejection fraction, evidence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, structural heart disease, altered left ventricular (LV) filling and raised brain natriuretic peptide (BNP).11 The complete pathophysiology is not known, however it is widely accepted that it is associated with cardiac and non-cardiac comorbidities.12 Cardiac abnormalities include altered atrial function, subtle alterations in LV systolic function and/or chronotropic incompetence.13 Non-cardiac comorbidities, for example hypertension, diabetes mellitus, anaemia, pulmonary or renal diseases and obesity may contribute to the HFpEF syndrome. In terms of pathophysiology, diastolic dysfunction is a prominent feature of HFpEF patients to which many factors contribute including both myocardial and vascular stiffening.14

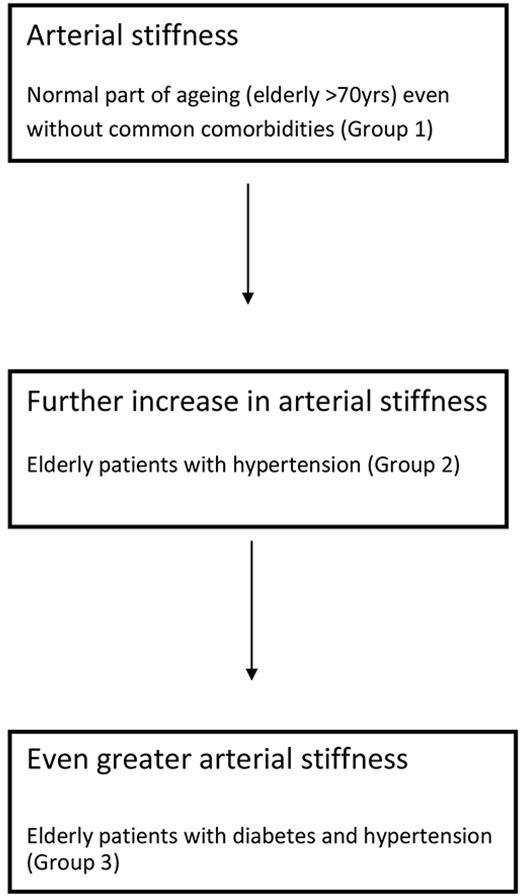

HFpEF patients are known to have altered vascular function. Balmain et al investigated the comparison in arterial compliance, venous capacitance and microvascular vasodilator function in three patients’ groups with HFpEF, HFrEF and normal volunteers (non-HF). All the groups had coronary artery disease.15 They found that there was reduced vascular compliance (increased arterial stiffness, decreased venous capacitance) in the HFpEF group compared with the HFrEF and non-HF groups. More recently, macrovascular and microvascular function was compared between HFpEF and hypertensive patients.10 This study found that there was decreased microvascular function with increase in arterial stiffness and depressed endothelial function in the forearm vasculature in the HFpEF group compared the hypertensive group. These studies highlight the fact that abnormal vasculature is present and may be an important contributor to the HFpEF syndrome. Although the groups in the above-mentioned studies were matched for age and sex, what remains unclear is why certain patients of the same age and sex suffer from HFpEF while others do not. There is good evidence that hypertension,16 diabetes mellitus17 and chronic kidney disease18 all increase vascular resistance on their own. Ageing itself is known to be an independent risk factor for arterial stiffness and increase in pulse wave velocity.19 20 It is therefore reasonable to consider that HFpEF may not be due to a primary cardiac pathology but rather an end-result of non-cardiac comorbidities affecting vascular function and resistance with perhaps some secondary cardiac involvement. We hypothesised therefore, that arterial stiffness increases with comorbidities, on top of effects of normal ageing (as illustrated in figure 1), contributing towards the HFpEF syndrome. It is possible that a gradual increase in arterial stiffness may be causing early fatigue of the cardiac muscles (as it struggles to pump into an ever-increasing high-pressure vascular circuit) resulting in elevation of left ventricular end diastolic pressure and subsequently HFpEF.21

Figure 1.

Overview of the hypothesis behind the IDENTIFY-HF study.

Methods

Study design

Single-centre, observational study in five age, sex and body mass index (BMI) matched groups varying on the presence or absence of diabetes, hypertension or heart failure.

Definitions

Heart failure in our study is defined as: (a) relevant symptoms/signs/radiographic findings as indicated by Boston criteria22 and (b) need for diuretic therapy. Preserved LV systolic function is defined as a LV ejection fraction (LVEF) of >50%, measured by echocardiography. Impaired LV systolic function will be defined as a LVEF of <40% in accordance with the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on heart failure. LVEF will be calculated using semi-quantitative assessment with 16 segment wall motion scoring.23 HFpEF, is defined as signs and symptoms of HF with LVEF >50% and raised natriuretic peptides (BNP >35 pg/mL or NT-proBNP >125 pg/mL) along with one other criteria: (i) structural heart disease (left atrial enlargement or left ventricular hypertrophy) on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), (ii) evidence of LV diastolic dysfunction based on ESC guidelines 2016 or iii) hospitalisation with heart failure within 12 months prior to study entry.

Hypertension is defined in this study as a documented resting clinic systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus will be defined according to the WHO criteria.24

Study setting

The study will be conducted at two sites: the cardiology research department at University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire (UHCW) NHS Trust and at the cardiac rehabilitation facility of the hospital (Atrium Health). The study assessments are expected to be undertaken during a single visit, however a second visit will be arranged if all the assessments are not completed.

Study population

Patients will be matched according to age, gender, BMI and allocated to five different groups. All patients will be aged 70 years or above.

The first four groups will constitute: Group A, normal healthy volunteers without major comorbidities including hypertension and diabetes; Group B, patients with hypertension without diabetes mellitus; Group C, patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus and Group D, patients with HFpEF. The fifth, parallel Group E will comprise the HFrEF group. In order to make meaningful comparison between the groups 21 patients each are planned to be recruited in groups A to D and 11 in group E determined by sample size calculation.

Aims

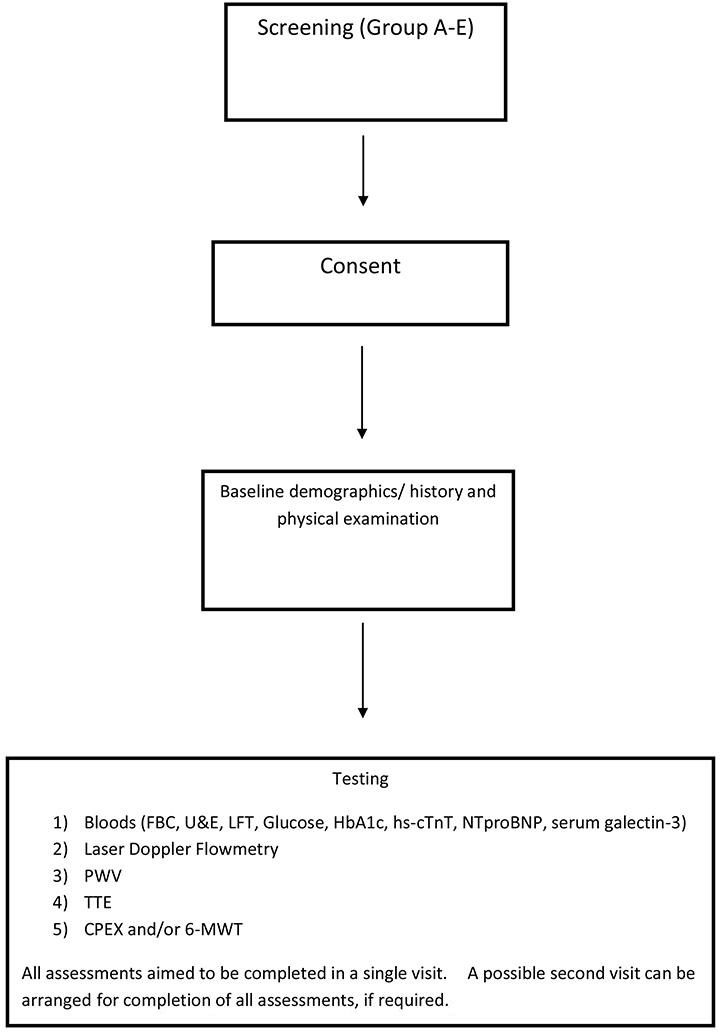

We plan to assess vascular function, and cardiovascular performance in different cohorts (figure 2). Arterial resistance measured by pulse wave velocity (PWV) will be the primary outcome measure and will be compared between Groups A to D. A separate comparison will be made between Groups D and E. We intend to investigate if there is increased arterial resistance from Group ‘A’ to Group ‘D’ and if there is a significant difference in arterial resistance between Groups ‘D’ and ‘E’. The secondary measures will focus on endothelial function (Laser Doppler measurements) and other cardiovascular performance measures; peak oxygen uptake (VO2) by cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPEX), and 6 min walk distance. Bloods samples will be taken for NT-proBNP, high sensitivity troponin T and serum will be stored for testing later for vascular biomarkers and galectin-3.

Figure 2.

Study flow chart. CPEX,cardiopulmonary exercise test; FBC, full blood count; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; hs-cTnT, high-sensitive cardiac troponin T; LFT, liver function test; PWV, pulse wave velocity; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; U&E, urea and electrolytes; 6-MWT,6 min walk test.

Inclusion criteria

Group A: healthy males or females aged ≥70 years without major systemic illnesses including hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

Group B: males or females aged ≥70 years with hypertension only.

Group C: males or females aged ≥70 years with hypertension and diabetes mellitus but without HF.

Group D: males or females aged >70 years with HFpEF.

Group E: males or females aged ≥70 years with HFrEF.

Exclusion criteria

Acute coronary syndrome (including myocardial infarction (MI)), cardiac surgery, other major cardiovascular surgery within 3 months or urgent percutaneous coronary intervention within 30 days of entry.

Patients who have had an MI, coronary artery bypass graft or other event within the 6 months prior to entry unless an echo measurement performed after the event confirms a LVEF ≥50%.

Current acute decompensated HF requiring intravenous therapy.

Alternative reason for shortness of breath such as: significant pulmonary disease or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, haemoglobin (Hb) <10 g/dL or BMI >40 kg/m2.

Severe left-sided valvular heart disease.

Hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg).

Severe liver failure.

Primary pulmonary hypertension.

Bedbound/immobile patients.

Chronic renal failure with creatinine of >250 μmol/l.

Significant peripheral vascular disease (PVD), defined as having signs of absent peripheral pulses or reported claudication pain or documented history of PVD.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

The sample size calculation is based on estimates obtained in studies reported by Balmain et al15 and Maréchaux et al.10 The aim is to detect a difference in the primary outcome; PWV, between the five groups of patients recruited to the study with the significance level being set at 5% if the p value is less than 0.05. The estimates range from a mean PWV of 8.6 m/s for the control group to 11.3 m/s for the HFpEF group and the within group SD is assumed to be SD=1.7 m/s and equal for each group. No estimate of the mean PWV was available in the literature for the hypertension and diabetes mellitus group, so this value was assumed to be in exactly in the middle of the hypertension and HFpEF mean. A sample size of n=11 for HFrEF patients and n=21 for all other groups will allow to detect a difference in PWV between the five groups for the aforementioned configuration of means and SD with 80% power using the overall F-test in a one-way analysis of variance. The study would additionally be sufficiently powered for the pair-wise comparison of the control group with the hypertension group and the control group with the HFpEF group. Statistical analysis will be performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.22.0. Descriptive statistics will be given as number (percentage), as average (±SD) or median (IQR).

Study procedures

Participants will attend our Research Unit in the morning. To avoid confounding factors for vascular measurements, participants and will be asked to abstain from caffeine and tobacco for 12 hours, and to omit their morning blood pressure medication. Vascular function studies will be carried out in a quiet, temperature-controlled (21°C to 23°C) room with subjects in the supine position, following at least 10 min of rest. Arterial compliance will be assessed using applanation tonometry to measure aortic PWV. Cutaneous microvascular function will be assessed by Laser Doppler flowmetry, after which the blood test and TTE measurements will be performed. Subsequently, patients will be asked to undertake the 6-MWT and CPEX test (figure 2).

Screening and recruitment

Group A: Participants will be recruited via the UHCW Hospital Radio, senior citizen’s group in the community and via friends and relatives of colleagues. These patients will receive an invitation letter and participant information sheet to read, they will then be contacted by the study coordinator at least 24 hours after receiving the invitation letter to answer any questions. If the participant is interested in taking part in the study, they will be invited for a screening visit at UHCW to confirm their eligibility. This will involve a full medical history, physical examination, blood pressure measurement and blood tests (full blood count, glucose, glycated haemoglobin and renal function). If the eligibility criteria are met, the study appointment will be organised.

Group B and C: Patients will be approached and screened for eligibility at the hypertension and diabetes outpatient clinics at UHCW. Eligible participants will receive an invitation letter and participant information sheet. They will then be contacted by the study coordinator at least 24 hours later to answer any questions, and to organise a study appointment.

Group D and E: Patients will be approached and screened for the eligibility criteria at the HF community clinic. Eligible participants will receive an invitation letter and participant information sheet. They will then be contacted by the study coordinator after at least 24 hours to answer any questions, and to organise a study appointment.

Study assessments

Participants in all groups will have the same assessments as follows (table 1):

Table 1.

Schedule of measures for every participant within the study

| Group A only: Separate screening visit prior to the study visit to check that the participants meet the eligibility criteria; full medical history, physical examination, blood pressure and blood tests (full blood count, Glucose, glycated haemoglobin and renal function) | |

| Time of day | Procedures/assessments* |

| Morning | Eligibility check |

| Informed consent | |

| Demographic data (date of birth, sex, ethnicity, height and weight) | |

| Relevant clinical history | |

| Current medications | |

| Blood pressure and heart rate | |

| Pulse wave velocity to measure arterial resistance | |

| Laser Doppler to measure microvascular function | |

| Blood tests: full blood count, renal function and electrolytes, liver function tests, NT-proBNP, high-sensitive cardiac troponin T. Samples will be frozen and stored for future analysis of vascular and other biomarkers, for example, galectin-3. | |

| Urine test: albumin and creatinine. samples will be frozen and stored for future analysis of metabolite profiles. | |

| Lunch | |

| Afternoon | Transthoracic echocardiography : tissue Doppler imaging and strain rate imaging |

| 6 min walk test | |

| Cardiopulmonary exercise test | |

All assessments will be aimed to be completed in a single visit. However, a possible second visit may be arranged either at Atrium Health or University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust for completion of all assessments, if required.

Heartrate and one brachial blood pressure measurement will be recorded over a 30 s time period. These measurements will be performed three times for each subject and averaged.

Blood tests will include full blood count, renal function and electrolytes, liver function tests, NT-proBNP and high-sensitive cardiac troponin T. Blood samples will be frozen in the Tissue Bank at UHCW for further tests such as vascular and other biomarkers for example, galectin-3 to be performed at a later date.

Urinalysis will be performed from a mid-stream urine sample obtained for albumin and creatinine levels. This will further be stored at the Tissue Bank UHCW to be analysed at a later date for metabolite profiles (‘metabolomics’), related to cardiovascular risk and insulin resistance.

TTE will include measurements of cardiac chamber sizes, ventricular function including LVEF, indices of LV diastolic function, assessment of valvular heart disease, tissue Doppler imaging and strain rate imaging. Furthermore, right ventricular structure and function and pulmonary artery pressures will be assessed.

Exercise tolerance will be assessed by a 6 min walk test and a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPEX) in each patient. The CPEX test will involve measurement of the oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production and heart rate and blood pressure monitoring while exercising on an exercise bike. Further details are provided below.

Pulse wave velocity protocol

Arterial resistance will be assessed using pulse wave velocity. Aortic PWV will be evaluated using a high-fidelity micromanometer (SPC-301; Millar Instruments, Texas, USA) coupled with the SphygmoCor system (SphygmoCor BPAS; PWV Medical, Sydney, Australia). A hand-held micromanometer-tipped probe will be applied to the skin overlying the radial, femoral and carotid arteries at the point of maximal arterial pulsation. Gated to a simultaneous ECG, the pulse wave will be recorded at each point. This data, in combination with the measured body surface distance between the two points, will be incorporated by the software programme to calculate PWV in metres per second (m/s). The measurements will be repeated three times and the average PWV will be used for analysis.

Laser doppler flowmetry protocol

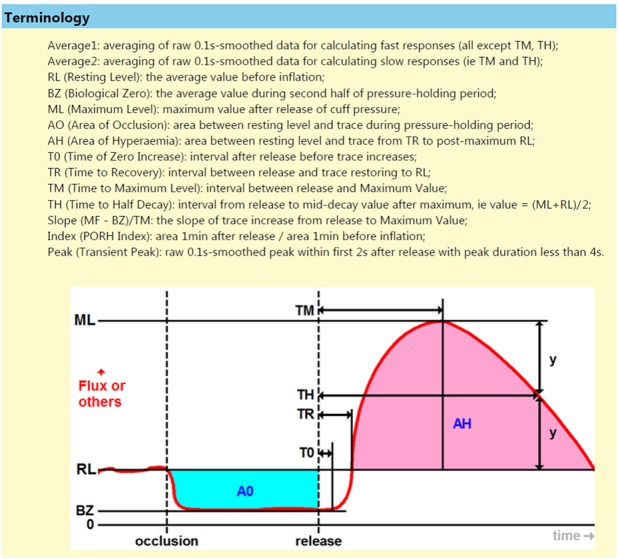

The forearm cutaneous blood flow will be measured at rest and during reactive hyperaemia by using Laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF), in accordance to the Fizeau-Doppler principle.25 Measurements of cutaneous blood flow will be expressed in perfusion units and the Laser Doppler signal will be continuously monitored on a computer (Moor instruments, VMS software V.4.06) coupled with Moor instruments system (moorVMS-VASC). The thenar eminence will be used for the placement of the LDF probe (VP1T/7), consistently at the same place, before and post the occlusive reactive hyperaemia manoeuvre. The room temperature will be maintained at 22°C during forearm cutaneous blood flow measurements. The reactive hyperaemia will be produced by occluding the forearm blood flow with a pneumatic cuff inflated to a pressure of 50 mm Hg above the SBP for 3 min. The signal obtained during complete arterial occlusion will be taken as the biological zero for cutaneous blood flow measurements before and during reactive hyperaemia. Resting flow will be taken as the average of a 6 min stable LDF recording. The definition of the measurements taken are shown in figure 3 and the power spectral density will be measured using the basic fast Fourier transform algorithm10

Figure 3.

Laser Doppler flowmetry for assessment of endothelial function. Schematic representation of flow (perfusion units) as a function of time in rest, after arterial occlusion and after cuff release. (adapted with permission of Moor diagnostics).

Cardiopulmonary exercise test & 6 minute walk test

Exercise tolerance will be assessed by 6 min walk test and CPEX, conducted in accordance with existing guidelines.26 27 For the walk test, participants will walk as far as possible in 6 min along a flat, obstacle free corridor, turning 180 degrees every 30 m. For CPEX, participants will pedal a cycle ergometer at 70 rpm until volitional fatigue, using a ramp protocol. Breath-by-breath measurement of oxygen (O2) consumption, 2carbon dioxide production and ventilation will be used to determine key cardiorespiratory parameters including peak O2 uptake2, VO2 at the anaerobic threshold2 and ventilatory efficiency.2 Blood pressure, ECG and O2 saturation will be continuously monitored. Criteria for a peak test will include respiratory exchange ratio >1.10.28

Blinding

In order to reduce observer-bias the operator involved in the assessments of the primary outcome (pulse wave velocity) will be blinded to the comorbidities of the group of patients (A to E).

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome will be a difference in arterial resistance between each of the five groups, as measured by aortic PWV. In addition, specific comparisons will be made between the control and hypertension groups as well as the control and HFpEF groups.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes are to assess and compare endothelial function and cardiovascular performance in all groups as measured by the following:

Blood tests: NTproBNP, high sensitivity troponin T, galectin-3.

Urinalysis: Albumin, Creatinine and metabolite profiles (‘metabolomics’), related to cardiovascular risk and insulin resistance.

Transthoracic echocardiography: Indices of LV diastolic function, tissue Doppler imaging, strain rate imaging and measuring flow with pulsed-wave Doppler echocardiography interrogating the LV outflow tract.

Exercise tolerance: 6 min walk test and a CPEX.

End of study definition

The study will be closed at the last patient’s study visit.

Study funding and sponsor

The study has been funded by a research grant from the West Midlands Clinical Research Network, National Institute of Health Research, UK. The study is sponsored by the Research, Development & Innovation department of the University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire NHS Trust (RDI, UHCW), UK.

Study oversight

The study will be monitored and overseen by the Study Management Group and the Research, Development and Innovation Department at UHCW.

Ethical approval and research governance

The study will be conducted in compliance with the principles of the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and in accordance with all applicable regulatory guidance, including, but not limited to, the Research Governance Framework and the Health Research Authority, UK. Progress reports and a final report at the conclusion of the study will be submitted to the approving research ethics committee within the timelines defined by the committee.

Patient and public involvement

Patient involvement has been crucial to the design of and protocol of the study. Detailed advice was obtained from patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives, which led to the tests being allowed to be done over two visits after screening. The non-invasive nature of the investigations was particularly favoured by the PPI group. Furthermore, optional transport was provided to participants following their recommendation. Patients seen in the relevant outpatient department will be invited to participate in the study. Ongoing PPI input is confirmed during the study steering committee meetings. The results of the study will be

disseminated to all the participants via post.

Dissemination and impact

The hypothesis on which this study is based has been published.10 The results of the study will be presented at national and international conferences and released in appropriate media outlets, including social media. The results are expected to be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented in local, national and international medical scientific congresses and meetings. The study is anticipated to shed light on whether vascular stiffness is an important determinant of HFpEF which in turn could potentially encourage research for new therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @HIITorMISSUK

Contributors: PB is the chief investigator for the study and DA leading on writing the protocol, ethics application and preparation of this manuscript. FPC, MOW, MAM all contributed fully to study design. GM, NC, SM, SE and RP contributed from their respective discipline and authored the relevant section of the protocol and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the regional research ethics committee (REC), West Midland and Black Country 17/WM/0039, UK, and permission to conduct the study in the hospital was also obtained from the RDI, UHCW NHS Trust.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, et al. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2014;171:368–76. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Chronic heart failure in adults: management. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg108 [PubMed]

- 3. Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, et al. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the acute decompensated heart failure national registry (adhere) database. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:76–84. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan MMY, Lam CSP. How do patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction die? Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:604–13. 10.1093/eurjhf/hft062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, et al. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2456–67. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banerjee P. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a clinical crisis. Int J Cardiol 2016;204:198–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.11.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zakeri R, Cowie MR. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: controversies, challenges and future directions. Heart 2018;104:377–84. 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, et al. Phenotype-Specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a multiorgan roadmap. Circulation 2016;134:73–90. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:263–71. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maréchaux S, Samson R, van Belle E, et al. Vascular and microvascular endothelial function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Card Fail 2016;22:3–11. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. Esc guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European Society of cardiology. developed in collaboration with the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–847. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B, et al. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:998–1005. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lam CSP, Lyass A, Kraigher-Krainer E, et al. Cardiac dysfunction and noncardiac dysfunction as precursors of heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction in the community. Circulation 2011;124:24–30. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.979203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borbély A, van der Velden J, Papp Z, et al. Cardiomyocyte stiffness in diastolic heart failure. Circulation 2005;111:774–81. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155257.33485.6D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balmain S, Padmanabhan N, Ferrell WR, et al. Differences in arterial compliance, microvascular function and venous capacitance between patients with heart failure and either preserved or reduced left ventricular systolic function. Eur J Heart Fail 2007;9:865–71. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mayet J, Hughes A. Cardiac and vascular pathophysiology in hypertension. Heart 2003;89:1104–9. 10.1136/heart.89.9.1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stehouwer CDA, Henry RMA, Ferreira I. Arterial stiffness in diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: a pathway to cardiovascular disease. Diabetologia 2008;51:527–39. 10.1007/s00125-007-0918-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang M-C, Tsai W-C, Chen J-Y, et al. Arterial stiffness correlated with cardiac remodelling in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology 2007;12:591–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00826.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. AlGhatrif M, Strait JB, Morrell CH, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of arterial stiffness and the role of blood pressure: the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Hypertension 2013;62:934–41. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mitchell GF. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage. J Appl Physiol 2008;105:1652–60. 10.1152/japplphysiol.90549.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Banerjee P. Heart failure: a story of damage, fatigue and injury? Open Heart 2017;4:e000684 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Remes J, Miettinen H, Reunanen A, et al. Validity of clinical diagnosis of heart failure in primary health care. Eur Heart J 1991;12:315–21. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on quantitation of two-dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1989;2:358–67. 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diabetes UK Available: www.diabetes.org.uk

- 25. Roustit M, Cracowski J-L. Non-invasive assessment of skin microvascular function in humans: an insight into methods. Microcirculation 2012;19:47–64. 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European respiratory Society/American thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428–46. 10.1183/09031936.00150314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Thoracic Society, American College of Chest Physicians . ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:211–77. author reply 1451 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Balady GJ, Arena R, Sietsema K, et al. Clinician's guide to cardiopulmonary exercise testing in adults: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2010;122:191–225. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e52e69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.