Abstract

Objectives

The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire is widely used to evaluate subjective symptoms of dry eye disease (DED) as a primary diagnostic criterion. This study aimed to develop a Japanese version of the OSDI (J-OSDI) and assess its reliability and validity.

Design and setting

Hospital-based cross-sectional observational study.

Participants

A total of 209 patients recruited from the Department of Ophthalmology at Juntendo University Hospital.

Methods

We translated and culturally adapted the OSDI into Japanese. The J-OSDI was then assessed for internal consistency, reliability and validity. We also evaluated the optimal cut-off value to suspect DED using an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis.

Primary outcome measures

Internal consistency, test–retest reliability and discriminant validity of the J-OSDI as well as the optimal cut-off value to suspect DED.

Results

Of the participants, 152 had DED and 57 did not. The J-OSDI total score showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.884), test–retest reliability (interclass correlation coefficient=0.910) and discriminant validity by known-group comparisons (non-DED, 19.4±16.0; DED, 37.7±22.2; p<0.001). Factor validity was used to confirm three subscales within the J-OSDI according to the original version of the questionnaire. Concurrent validity was assessed by Pearson correlation analysis, and the J-OSDI total score showed a strong positive correlation with the Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score (γ=0.829). The optimal cut-off value of the J-OSDI total score was 36.3 (AUC=0.744).

Conclusions

The J-OSDI was developed and validated in terms of reliability and validity as an effective tool for DED assessment and monitoring in the Japanese population.

Keywords: dry eye disease, ocular surface disease index, OSDI, reliability, validity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides the first validation data on the Japanese version of the cular Surface Disease Index (J-OSDI) questionnaire as the primary evaluation for dry eye disease (DED) diagnosis.

We conducted a cross-cultural adaptability thoroughly compared by a committee of experts for conceptual equivalence.

This study confirmed the reliability and validity of the J-OSDI in the 209 patients.

The main limitation is that this study was conducted at a single university hospital, which may limit the generalisability of the findings.

The validated J-OSDI allows across-country epidemiological comparisons of patient-reported subjective symptoms of DED.

Introduction

The prevalence of dry eye disease (DED) continues to grow due to several psychosocioeconomic factors, including an increase in digital screen usage time, an ageing population and stressful social environments.1 2 DED can cause ocular surface damage, eye discomfort and impaired vision and can also lead to substantial economic problems due to decreased quality of life and work productivity.3 4 Therefore, quantifying the symptoms and severity of DED is important for the diagnosis, monitoring and treatment of the condition.5 6

Diagnosis of DED can be made using various methods, including tear film breakup time (TFBUT), ocular surface staining and osmolarity as a homeostasis marker. Additionally, the use of a questionnaire to determine if symptoms of DED are present is recommended as a primary examination method in the DED diagnosis protocol by the TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report and in the 2016 Asia Dry Eye Society (ADES) consensus report.7 8 Although previous research has established a divergence between the subjective symptoms of DED and clinical severity of the disease,9–11 questionnaires that can quantitatively measure the subjective symptoms of DED are indispensable for DED diagnosis and management.

The 2016 dry eye diagnostic criteria published by the ADES8 recommend that DED be diagnosed according to both subjective symptoms and TFBUT, indicating that subjective symptoms are now widely recognised as playing an important role in DED. We previously showed that this change in diagnostic criteria could lead to a 28.0% increase in DED patients in Japan2; thus, the need for effective DED treatments may increase in the future. Both the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) and the Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score (DEQS)12 are widely used to assess subjective symptoms of DED in Japan, but the reliability and validity of the OSDI have not been confirmed in Japan.13 Determining the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the OSDI (J-OSDI) is essential for making epidemiological and symptomatic comparisons with other countries.13–16

In this study, we developed and evaluated the reliability and validity of the J-OSDI and determined the cut-off value of the J-OSDI total score using the 2016 diagnostic criteria put forth by the ADES.8

Materials and methods

OSDI questionnaire

The OSDI questionnaire contains 12 questions divided into three subscales: ocular symptoms, vision-related function and environmental triggers.13 The questionnaire asks patients to rate each symptom on a 5-point scale according to their frequency, from ‘all of the time’ (score 4) to ‘none of the time’ (score 0). The OSDI total score and each subscale score are separately translated to scores of 0–100. According to the OSDI total score, patients are classified as normal (0–12 points), or as having mild (13–22 points), moderate (23–32 points) or severe DED (33–100 points).

Translation of the Japanese version of the OSDI

To obtain a scientifically accurate translation and to perform a transcultural validation of the original version of the questionnaire, a forward-backward procedure was applied to translate the OSDI (Allegan, Irvine, California, USA) from English to Japanese following previously established guidelines.17–19 First, a forward translation was carried out independently by five bilingual ophthalmologists to produce a consensus version. A cultural adaptation was conducted to ensure that the translated questionnaire is easily understandable by Japanese patients. Second, the consensus version was back-translated into English by two native-English researchers and was assessed for comprehensibility. Finally, the original translated and back-translated versions were thoroughly compared by a committee of experts for conceptual equivalence. The J-OSDI is provided for others to use in online supplementary figure 1.

bmjopen-2019-033940supp001.pdf (43.8KB, pdf)

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional observational study. Adult patients (aged 20 years) who visited the Department of Ophthalmology at Juntendo University Hospital in Tokyo, Japan, between September 2017 to May 2018 were included. Of them, we excluded patients with best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) values <20/20 and those with a history of eyelid disorder, ptosis, Parkinson disease, ocular surface surgery, eyelid surgery, hereditary corneal disease or any other disease that could affect blinking. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in Brazil in 2013.

All patients underwent a complete ophthalmic evaluation for both eyes, including measuring BCVA, intraocular pressure (IOP) and subjective symptoms. Additionally, TFBUT, corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) for keratoconjunctival vital staining, maximum blink interval (MBI) and Schirmer test I for reflex tear production were assessed for both eyes. TFBUT, CFS and Schirmer test I values from the worst eye were examined. The mean value of the MBI was used in accordance with a previous study.20 For each patient, we evaluated the TFBUT, CFS and MBI before performing Schirmer test I. We diagnosed DED and non-DED using the ADES 2016 diagnostic criteria,8 which are based on two positive items: the presence of subjective symptoms and decreased TFBUT (≤5 s).

Environmental conditions

The temperature and humidity of the examination room were controlled at 26°C in the summer and 24°C in the winter with 50% relative humidity, according to the Guideline for Design and Operation of Hospital HVAC Systems established by the Healthcare Engineering Association of Japan.21

Other instruments for DED diagnosis and management

Subjective symptoms were evaluated by interviewing subjects with DED. The DEQS questionnaire was administered to subjects in order to assess the severity of dry eye-associated symptoms and the multifaceted effects of DED on daily life.12 The score derived from this questionnaire is a subjective measurement of DED symptoms, where 0 indicates the best score (no symptoms) and 100 indicates the worst score (maximum symptoms).

TFBUT was measured using a fluorescein dye according to the standard methodology.8 Only a small quantity of dye was administered using the wetted fluorescein strip in order to minimise the effect of the dye on tear volume and TFBUT. Each subject was instructed to blink three times after the dye was applied to ensure adequate mixing of the dye and tears. The time interval between the last blink and the appearance of the first dark spot on the cornea was measured with a stopwatch. The mean value of three measurements was used. A cut-off value of TFBUT ≤5 s was used to diagnose DED.8

CFS was graded according to the van Bijsterveld grading system,22 which divides the ocular surface into three zones: the nasal bulbar conjunctiva, the temporal bulbar conjunctiva and the cornea. Each zone was evaluated on a scale of 0–3, with 0 indicating no staining and 3 indicating confluent staining. The maximum possible score was thus 9.

The MBI was considered as the length of time that subjects could keep their eyes open before blinking.20 We calculated the MBI twice by stopwatch under a light microscope without using the light. The MBI was recorded as 30 s if the blink interval exceeded 30 s.

Schirmer test I was performed without topical anaesthesia after all other examinations had been completed. Schirmer’s test strips (Ayumi Pharmaceutical Co, Tokyo, Japan) were placed on the outer third of the temporal lower conjunctival fornix for 5 min. The strips were then removed, and the length of dampened filter paper (in mm) was recorded.

Statistical analyses

To compare general characteristics between DED and non-DED participants, two-tailed t-tests were used for continuous variables and χ2 tests were used for categorical variables. Pearson rank correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the correlations between J-OSDI, DEQS, TFBUT, CFS, MBI and Schirmer test I results. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to determine the optimal cut-off value of the J-OSDI total score for suspecting DED. The area under the curve (AUC) was computed using the trapezoidal rule. Data are presented as mean±SD or proportion (%). Statistical analyses were performed using STATA V.15 and SPSS Statistics V.1.0.0. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Reliability

The internal consistency of the J-OSDI was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, with an alpha >0.70 considered to be acceptable.23 Test–retest reliability was evaluated by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) values from the first and second entries. An ICC value of ≥0.70 was considered acceptable for test–retest reliability.24

Validity

Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the non-DED and DED groups. For factor validity, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted by an equamax rotation to determine whether the subscales in the J-OSDI clustered together in the same manner as in the original OSDI. Factors with an eigenvalue >0.90 were retained. Concurrent validity was assessed by calculating the correlations (Pearson coefficients) between the J-OSDI total score or subscale scores and the DEQS or other clinical results, including TFBUT, CFS, MBI and Schirmer test I values.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the research design and conception of this research study.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study participants. All subjects responded to the questionnaires, completed the examination and were eligible for the study. Overall, 209 participants were included. The average age was 58.9±15.3 years, and 83.7% of the participants were women. Using the diagnostic criteria put forth by the ADES,8 152 and 57 patients were classified as DED (72.7%) and non-DED (27.3%), respectively. The mean BCVA value for both eyes was −0.1±0.0 logMAR. The mean IOP for both eyes was 14.0±2.8 mm Hg. Both the J-OSDI total score and the DEQS were significantly higher in the DED group than in the non-DED group, indicating that DED patients showed a greater rate of subjective symptoms. Furthermore, both TFBUT and the MBI were significantly lower in the DED group than in the non-DED group. Neither BCVA, IOP, CFS nor the Schirmer test I results differed significantly between DED and non-DED participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Non-DED | DED | P value | Total | |

| n=57 | n=152 | n=209 | ||

| Age, year±SD | 61.4±15.5 | 57.9±15.2 | 0.149 | 58.9±15.3 |

| Gender, female (%) | 48 (84.2) | 127 (83.6) | 1.000 | 175 (83.7) |

| BCVA, logMAR±SD | −0.1±0.0 | −0.1±0.0 | 0.513 | −0.1±0.0 |

| IOP, mm Hg±SD | 14.6±2.9 | 13.8±2.7 | 0.062 | 14.0±2.8 |

| Subjective symptoms, yes (%) | 5 (8.8) | 152 (100) | ***<0.001 | 157 (75.1) |

| J-OSDI, 0–100±SD | 19.4±16.0 | 37.7±22.2 | ***<0.001 | 32.7±29.7 |

| DEQS, 0–100±SD | 16.0±14.7 | 32.7±21.6 | ***<0.001 | 28.1±21.3 |

| TFBUT, s±SD | 2.5±2.4 | 1.5±0.8 | ***<0.001 | 1.7±1.5 |

| CFS, 0–9±SD | 2.8±2.5 | 3.3±2.6 | 0.192 | 3.2±2.6 |

| Schirmer I, mm±SD | 7.2±8.2 | 5.7±6.2 | 0.162 | 6.1±6.8 |

| MBI, s±SD | 15.1±8.1 | 10.5±6.3 | ***<0.001 | 11.7±7.1 |

P values were determined using the Student’s t-test (two-tailed) for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

***p<0.001.

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; CFS, corneal fluorescein staining;DED, dry eye disease; DEQS, Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score; IOP, intraocular pressure; J-OSDI, Japanese version of Ocular Surface Disease Index; MBI, maximum blink interval; TFBUT, tear film breakup time.

Reliability

We tested the J-OSDI total score and subscale scores for internal consistency and test–retest reliability, and the results are shown in table 2. For internal consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.884 for the J-OSDI total score and 0.788, 0.669 and 0.902 for the ocular symptoms, vision-related function and environmental triggers subscales, respectively. Test–retest reliability was evaluated in 173 participants, with a median (IQR) period of 119 (81–182) days between the test and retest. The ICC values were 0.910, 0.649, 0.817 and 0.859 for the J-OSDI total score, ocular symptoms subscale, vision-related function subscale and environmental triggers subscale, respectively.

Table 2.

Reliability for each subscale

| No of items | Cronbach's αlpha | ICC | |

| n=209 | n=173 | ||

| J-OSDI total score | 12 | 0.884 | 0.910 |

| Ocular symptoms | 5 | 0.788 | 0.649 |

| Vision-related function | 4 | 0.669 | 0.817 |

| Environmental triggers | 3 | 0.902 | 0.859 |

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; J-OSDI, Japanese version of the Ocular Surface Disease Index.

Discriminant validity

Table 3 shows the mean values for the J-OSDI total score, each of the subscale scores and each of the component scores. The mean J-OSDI total score was significantly higher in the DED group than in the non-DED group (DED, 37.7±22.2; non-DED, 19.4±16.0; p<0.001). Additionally, all three subscales were significantly higher in the DED group than in the non-DED group (ocular symptoms: DED, 34.6±21.6; non-DED, 20.9±17.4; p<0.001; vision-related function: DED, 36.5±27.7; non-DED, 20.8±22.0; p<0.001; environmental triggers: DED, 45.2±29.7; non-DED, 15.5±19.8; p<0.001). Eleven of the 12 (92%) component scores were significantly higher in the DED group than in the non-DED group, with only question 2 showing a non-significant difference.

Table 3.

J-OSDI score for each question

| Classification, score ±SD, score | Non-DED | DED | P value | Total |

| n=57 | n=152 | n=209 | ||

| J-OSDI total score, 0–100 | 19.4±16.0 | 37.7±22.2 | ***<0.001 | 32.7±22.2 |

| Ocular symptoms, 0–100 | 20.9±17.4 | 34.6±21.6 | ***<0.001 | 30.9±21.4 |

| 1. Eyes that are sensitive to light? | 0.8±0.9 | 1.5±1.3 | ***<0.001 | 1.3±1.3 |

| 2. Eyes that feel gritty? | 0.8±1.2 | 1.0±1.0 | 0.338 | 1.0±1.1 |

| 3. Painful or sore eyes? | 0.4±0.7 | 1.0±1.0 | ***<0.001 | 0.8±1.0 |

| 4. Blurred vision? | 1.1±1.0 | 1.6±1.2 | **0.002 | 1.5±1.2 |

| 5. Poor vision? | 1.1±1.1 | 1.8±1.3 | ***<0.001 | 1.6±1.3 |

| Vision-related function | 20.8±22.0 | 36.5±27.7 | ***<0.001 | 32.2±27.2 |

| 6. Reading? | 0.8±1.1 | 1.6±1.3 | ***<0.001 | 1.4±1.3 |

| 7. Driving at night? | 0.4±0.6 | 1.1±1.4 | *0.022 | 0.9±1.3 |

| 8. Working with a computer or bank machine (ATM)? | 1.1±1.3 | 1.6±1.4 | *0.030 | 1.5±1.4 |

| 9. Watching TV? | 0.7±1.0 | 1.3±1.2 | **0.002 | 1.1±1.1 |

| Environmental triggers | 15.5±19.8 | 45.2±29.7 | ***<0.001 | 37.1±30.4 |

| 10. Windy conditions? | 0.7±0.9 | 1.9±1.4 | ***<0.001 | 1.5±1.3 |

| 11. Places or areas with low humidity (very dry)? | 0.5±0.8 | 1.6±1.3 | ***<0.001 | 1.3±1.3 |

| 12. Areas that are air conditioned? | 0.6±0.9 | 2.0±1.3 | ***<0.001 | 1.6±1.3 |

P values were determined using the Student’s t-test.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001.

DED, dry eye disease; J-OSDI, Japanese version of Ocular Surface Disease Index.

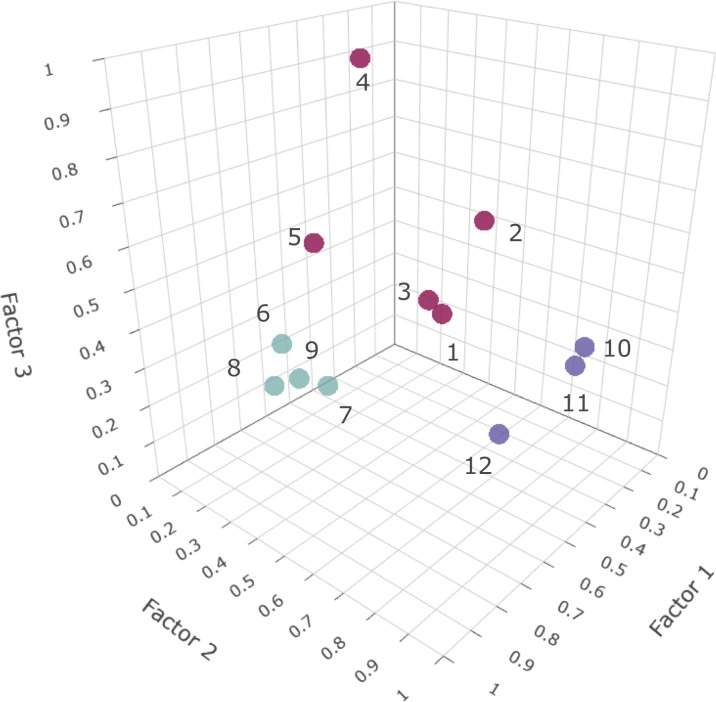

Factor validity

Factor validity was assessed by confirmatory factor analysis to determine the subscales. As shown in figure 1, correspondent with the three homogeneous content domains that were identified and constructed, three factors were rotated to an equamax solution. These three factors accounted for 71.9% of the total variance, and each factor comprised sets of items that were interpretable and relevant in content. Factor 1, accounting for 53.0% of the total variance and 23.6% of the common variance, comprised items assessing the frequency of ocular symptoms (five items). Factor 2, accounting for 11.1% of the total variance and 22.8% of the common variance, comprised items assessing the frequency of vision-related function (four items). Factor 3, accounting for 7.7% of the total variance and 17.7% of the common variance, comprised items assessing the frequency of environmental triggers (three items). All factors were in accordance with the subscales in the original version. The factor matrix of each J-OSDI component can be viewed in online supplementary table 1. All subscales and the total instrument underwent formal reliability and validity testing.

Figure 1.

Three subscales of the J-OSDI as determined by factor analysis. The existence of three clusters that were used as subscales are shown. These were in accordance with the subscales that are used in the original version of the OSDI: vision-related function (components 1–5), ocular symptoms (components 6–9) and environmental triggers (components 10–12).

bmjopen-2019-033940supp002.pdf (95.9KB, pdf)

Concurrent validity

Table 4 shows the correlations between the J-OSDI total score, subscale scores and other clinical items related to DED diagnosis, including DEQS, TFBUT, CFS, Schirmer test I results and the MBI. The J-OSDI total score showed a significant strong positive correlation with the DEQS (γ=0.829). Among the clinical items related to DED diagnosis, there was a modest but significant negative correlation between the J-OSDI total score and MBI (γ=−0.258). The subscales were each significantly and positively correlated with the DEQS (γ=0.786, 0.702 and 0.650, respectively), while ocular symptoms and environmental triggers were significantly and negatively correlated with the MBI (γ=−0.195 and −0.370, respectively).

Table 4.

Correlation between the J-OSDI total score and other clinical assessments

| Clinical items | J-OSDI total score | Ocular symptoms | Vision-related function | Environmental triggers | ||||

| γ | P value | γ | P value | γ | P value | γ | P value | |

| DEQS | 0.829 | ***<0.001 | 0.786 | ***<0.001 | 0.702 | ***<0.001 | −0.650 | ***<0.001 |

| TFBUT | −0.066 | 0.349 | −0.044 | 0.532 | −0.057 | 0.416 | −0.131 | 0.063 |

| CFS | 0.018 | 0.791 | −0.013 | 0.852 | −0.137 | *0.049 | 0.161 | *0.022 |

| Schirmer I | −0.090 | 0.195 | −0.013 | 0.844 | −0.071 | 0.311 | −0.129 | 0.067 |

| MBI | −0.283 | ***<0.001 | −0.215 | **0.002 | −0.135 | 0.053 | −0.407 | ***<0.001 |

Pearson rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlations between the J-OSDI total score and subscale scores and various clinical assessments.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001.

CFS, corneal fluorescein staining; DEQS, Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score;J-OSDI, Japanese version of the Ocular Surface Disease Index; MBI, maximum blink interval; TFBUT, tear film breakup time.

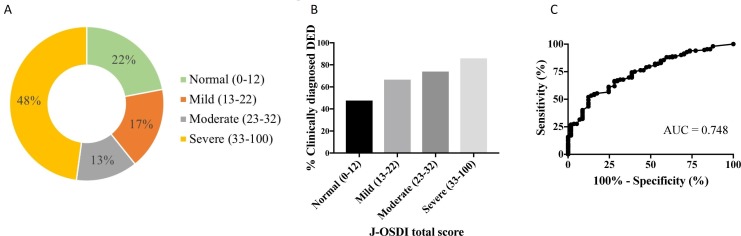

J-OSDI severity results and cut-off value for detecting DED

Figure 2A shows the proportion of DED participants in each severity category as determined by the J-OSDI total score. The clinically diagnosed DED patients were divided according to their J-OSDI scores as follows: 22.0% were categorised as normal, 17.2% were categorised as mild DED, 12.9% were categorised as moderate DED and 47.8% were categorised as severe DED. Figure 2B shows the proportion of patients who were clinically diagnosed with DED in each severity category determined by the J-OSDI total scores. Overall, 47.8% of the patients who were classified as normal by their J-OSDI total score were clinically diagnosed with DED, while 66.7%, 74.0% and 86.0% of patients classified as mild, moderate and severe, respectively, were clinically diagnosed with DED. Figure 2C shows the ROC curve of the J-OSDI total score from the non-DED and DED groups, which was used to determine the diagnostic efficacy of the J-OSDI total score. The optimum cut-off value for detecting DED was 36.3 points, with an AUC, sensitivity and specificity of 0.744, 51.3% and 87.7%, respectively. Online supplementary table 1 shows the details of the J-OSDI total score sensitivity and specificity analysis.

Figure 2.

Clinical utility of the J-OSDI for evaluating DED. (A) The proportion of patients in each DED severity category as determined by the J-OSDI total score. (B) The proportion of patients who were clinically diagnosed with DED by category of severity according to the J-OSDI total score. (C) The receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve for the diagnosis of DED determined by the Asia Dry Eye Society 2016 criteria using the J-OSDI. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is 0.744.

Discussion

This study developed, and assessed the reliability and validity, of the J-OSDI, which is the Japanese version of OSDI, and determined a cut-off value for detecting DED using the ADES diagnostic criteria of 2016. Our results validate the use of the J-OSDI in Japan and make it possible to compare epidemiological results between Japan and other countries.

In this study, the J-OSDI total score showed both high internal consistency and test–retest reliability (table 2). The factor analysis confirmed three subscales within the J-OSDI, ocular symptoms, vision-related function, and environmental triggers, in accordance with the subscales in the original English version (figure 1).13 The environmental triggers subscale showed good internal consistency and reliability, whereas the other two subscales, ocular symptoms and vision-related function, showed lower internal consistency and reliability compared with environmental triggers. Vision-related function only showed modest internal consistency. Internal consistency denotes whether all items of an instrument measure the same characteristic.25 In the sensitivity analysis, deleting question item 7 (ie, night driving) provided the highest ICC value of 0.74 (online supplementary table 2). This study was conducted in central Tokyo, where the traffic network was developed, and numerous elderly people were included. Therefore, question item 7 on night driving may have affected the internal consistency. This result indicates that the question items included in OSDI need to be adjusted to the changing demands. The ocular symptoms of DED patients have typically varied because of the known fluctuations in the subjective symptoms of DED,26 27 thus violating this assumption of reliability.

The discriminant validity of the J-OSDI was verified from the finding that the J-OSDI total score and subscale scores were significantly higher in the DED group than in the non-DED group (table 3). Further, the percentage of participants who were clinically diagnosed with DED increased proportionally in each severity category, indicating that the J-OSDI total score can discriminate DED (figure 2B). Our study also determined that the optimal J-OSDI total score cut-off value for detecting DED according to the ADES criteria was 36.3. One previous study reported an OSDI total score cut-off value of 15.13 However, the difference between this cut-off value and that of the current study is probably the result of differences in the methods used to clinically diagnose the severity of DED, as the previous study used lissamine green staining, Schirmer test I, and patient perception of ocular symptoms. In contrast, the current study used TFBUT as an essential part of the diagnostic criteria.7 8 Online supplementary table 3 shows the sensitivity and specificity of our reported optimal cut-off value and the sensitivity and specificity for the different severity categories: normal (0–12), mild (13–22), moderate (23–32) and severe (33–100).13 Our results suggest that it is necessary to re-evaluate the OSDI total score cut-off values for diagnosis and the severity categories to reflect the changes made to the diagnostic criteria for DED.7 8 28–33

Table 4 shows the correlations between the J-OSDI total score and other clinical tests, including DEQS, TFBUT, CFS, MBI and Schirmer test I. The J-OSDI total score showed a strong positive correlation with the DEQS. Because the DEQS has been validated in Japan,12 this result supports the use of the J-OSDI as a valid method of quantifying subjective symptoms. In contrast, the respective correlations between the J-OSDI total score and TFBUT, CFS and Schirmer I were relatively low. This is consistent with previous studies that reported low correlations and high divergence between subjective symptoms assessed by questionnaires and clinical tools,2 24 30 underscoring the importance of combining knowledge about subjective symptoms and clinical tools in order to effectively evaluate and monitor DED. Our group20 has proposed the MBI as a simple self-check screening test for DED because it is highly correlated with subjective symptoms compared with other dry eye items (table 4). Because of the divergence between the subjective and clinical symptoms of DED,2 it is necessary to perform multilateral evaluations using not only the OSDI total scores but also the subscales and each component. In the present study, we assessed the respective relationship between each subscale and various clinical tools for DED examination and found that the ocular symptoms and environmental trigger subscales were negatively correlated with MBI. We recently reported that the MBI is also significantly associated with TFBUT and CFS.20 Our previous results and those of this study suggest that the MBI reflects both TFBUT and CFS results, possibly explaining its negative correlation with the ocular symptoms and environmental triggers subscale scores of the J-OSDI.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted at a single university hospital in Japan, possibly introducing selection bias into our sample. Second, under the simplified ADES diagnostic criteria, those with low TFBUTs can still be classified as non-DED due to lack of subjective symptoms; thus, our non-DED group showed a low TFBUT. Third, the test–retest method that we used to confirm reliability introduced recall bias due to the required length of the test–retest period between 2 days and 2 weeks.34 Next, we did not account for differences in variables such as socioeconomic status or education level, possibly affecting the responses. Finally, this study was designed to investigate the J-OSDI as a primary evaluation and monitoring method for DED. Thus, rose bengal stain scores, tear osmolality, meibomian gland dysfunction assessments and corneal sensations were not applied in this study. Despite these limitations, we verified the reliability and validity of the J-OSDI for DED assessment and monitoring in Japan.

In summary, we developed and validated the J-OSDI by assessing its reliability and validity. We report that a J-OSDI score of 36.3 is the optimal cut-off value for suspecting DED under the 2016 ADES criteria. We believe that the J-OSDI will be useful for primary assessment and monitoring of DED in routine clinical practice and in remote diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nurses and orthoptists of the Department of Ophthalmology at the Juntendo University Hospital for collecting the data for DED diagnosis.

Footnotes

Twitter: @eyetake

Contributors: AM-I: performance of the research, data collection, data analysis and writing of the paper. TI: performance of the research, research design, data analysis and writing of the paper. SN and MI: research design, data analysis. MN: data analysis. FK, YO, NI, AE and HH: data collection, data analysis. HKi: performance of the research. AM and HKo: research design, writing of the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee at Juntendo University Hospital (approval number, 17–088 and 18–141).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf 2017;15:334–65. 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inomata T, Shiang T, Iwagami M, et al. Changes in distribution of dry eye disease by the new 2016 diagnostic criteria from the Asia dry eye Society. Sci Rep 2018;8:1918 10.1038/s41598-018-19775-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea 2011;30:379–87. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181f7f363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uchino M, Uchino Y, Dogru M, et al. Dry eye disease and work productivity loss in visual display users: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:294–300. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inomata T, Nakamura M, Iwagami M, et al. Risk factors for severe dry eye disease: Crowdsourced research using DryEyeRhythm. Ophthalmology 2019;126:766–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heidari M, Noorizadeh F, Wu K, et al. Dry eye disease: emerging approaches to disease analysis and therapy. J Clin Med 2019;8. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf 2017;15:539–74. 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tsubota K, Yokoi N, Shimazaki J, et al. New perspectives on dry eye definition and diagnosis: a consensus report by the Asia dry eye Society. Ocul Surf 2017;15:65–76. 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bourcier T, Acosta MC, Borderie V, et al. Decreased corneal sensitivity in patients with dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:2341–5. 10.1167/iovs.04-1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hay EM, Thomas E, Pal B, et al. Weak association between subjective symptoms or and objective testing for dry eyes and dry mouth: results from a population based study. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:20–4. 10.1136/ard.57.1.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu KP, Yagi Y, Tsubota K. Decrease in corneal sensitivity and change in tear function in dry eye. Cornea 1996;15:235–9. 10.1097/00003226-199605000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sakane Y, Yamaguchi M, Yokoi N, et al. Development and validation of the dry Eye-Related quality-of-life score questionnaire. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013;131:1331–8. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and validity of the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:615–21. 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pakdel F, Gohari MR, Jazayeri AS, et al. Validation of Farsi translation of the ocular surface disease index. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2017;12:301–4. 10.4103/jovr.jovr_92_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zheng B, Liu X-J, Sun Y-QF, et al. Development and validation of the Chinese version of dry eye related quality of life scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:145 10.1186/s12955-017-0718-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Santo RM, Ribeiro-Ferreira F, Alves MR, et al. Enhancing the cross-cultural adaptation and validation process: linguistic and psychometric testing of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of a self-report measure for dry eye. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:370–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-Cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1417–32. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000;25:3186–91. 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Castro JSde, Selegatto IB, Castro RSde, et al. Translation and validation of the Portuguese version of a dry eye disease symptom questionnaire. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2017;80:14–16. 10.5935/0004-2749.20170005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inomata T, Iwagami M, Hiratsuka Y, et al. Maximum blink interval is associated with tear film breakup time: a new simple, screening test for dry eye disease. Sci Rep 2018;8:13443 10.1038/s41598-018-31814-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Healthcare Engineering Association of Japan Standard Working Group The Guideline for design and operation of hospital HVAC systems, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Bijsterveld OP. Diagnostic tests in the sicca syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1969;82:10–14. 10.1001/archopht.1969.00990020012003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951;16:297–334. 10.1007/BF02310555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL. Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. statistics and strategies for evaluation. Control Clin Trials 1991;12:S142–58. 10.1016/S0197-2456(05)80019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess 2003;80:99–103. 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nepp J, Wirth M. Fluctuations of Corneal Sensitivity in Dry Eye Syndromes--A Longitudinal Pilot Study. Cornea 2015;34:1221–6. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alves M, Reinach PS, Paula JS, et al. Comparison of diagnostic tests in distinct well-defined conditions related to dry eye disease. PLoS One 2014;9:e97921 10.1371/journal.pone.0097921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schirmer O. Studien Zur Physiologie und Pathologie Der Tränenabsonderung und Tränenabfuhr. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1903;56:197–291. 10.1007/BF01946264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimazaki J. Definition and criteria of dry eye. Ganka 1995;37:765–70. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lemp MA. Report of the National eye Institute/Industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. Clao J 1995;21:221–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the definition and classification Subcommittee of the International dry eye workshop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5:75–92. 10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70081-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shimazaki JTK, Kinoshita S, Ohashi Y. Definition and diagnosis of dry eye 2006. Atarashii Ganka 2007;24:181–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33. AAO Cornea/External Disease PPP Panel HCfQEC Dry eye syndrome, 2013. Available: https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/dry-eye-syndrome-ppp-2013 [Accessed 30 Dec 2016].

- 34. Marx RG, Menezes A, Horovitz L, et al. A comparison of two time intervals for test-retest reliability of health status instruments. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:730–5. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00084-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033940supp001.pdf (43.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033940supp002.pdf (95.9KB, pdf)