Abstract

Objective

This study was designed to evaluate the applicability and effectiveness of the enhanced informed consent form (ICF) methodology, proposed by the Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review (SIDCER), in paediatric research requiring parental consent. The objective of this study was to compare the parental understanding of information between the parents who read the SIDCER ICF and those who read the conventional ICF.

Design

A prospective, randomized, controlled design.

Setting

Paediatric Outpatients Department, Phramongkutklao Hospital, Thailand.

Participants

210 parents of children with thalassemia (age=35.6 ± 13.1 years).

Interventions

The parents were randomly assigned to read either the SIDCER ICF (n=105) or the conventional ICF (n=105) of a paediatric drug trial.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Parental understanding of trial information was determined using 24 scenario-based questions. The primary endpoint was the proportion of parents who obtained the understanding score of more than 80%, and the secondary endpoint was the total score.

Results

Forty-five parents (42.9%) in the SIDCER ICF group and 29 parents (27.6%) in the conventional ICF group achieved the primary endpoint (relative risk=1.552, 95% CI 1.061 to 2.270, p=0.021). The total score of the parents in the SIDCER ICF group was significantly higher than the conventional ICF group (18.07±3.71 vs 15.98±4.56, p=0.001).

Conclusions

The SIDCER ICF was found to be superior to the conventional ICF in improving parental understanding of trial information.

Keywords: informed consent, parental consent, pediatrics, consent forms, comprehension

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was a comparative, randomized-controlled study, in which the SIDCER ICF (study intervention) was directly compared with the conventional ICF (control) to establish superiority.

This study was conducted on actual parents deciding whether or not to allow their child to participate in a paediatric drug trial.

This study was confined to the parental understanding of an ICF while the child’s understanding of an assent form was not studied.

The findings were largely confined to research contexts in Thailand and may not account for other settings.

Introduction

In paediatric research, enrollment of child subjects generally requires parental permission.1 Adequate parental understanding of trial information is one of the keys to the ethical conduct of paediatric research because informed parents can act, as proxy decision makers, in their child’s best interests and protect their child from assuming unreasonable risks.2 Despite increasing ethical and regulatory scrutiny, deficiencies still exist in parental understanding; some parents have consented to research without understanding the experimental nature of it and the risks involved, or even that they are consenting on behalf of their child.3–7

An informed consent form (ICF) serves as a mandatory document to provide trial relevant information to the participants/surrogate decision makers and document their consent; it consists of the information sheet and the consent certificate. Although the form alone may not be sufficient to achieve a proper, valid consent, it does serve multiple purposes in clinical trials, including the assurance of complete disclosure of information and the enhancement of participants’ comprehension.8 Ideally, an ICF given to parents in paediatric research should be complete, concise and understandable so that it would enable them to come to an informed decision in regard to their child’s participation in a study.9 In reality, empirical observations reveal a number of lengthy, detailed and complicated ICFs which are unlikely to be read and understood by general laypersons.10–12 Most ICF templates still seem to require a high level of reading comprehension.13 It has been suggested that the written language in quite a few ICFs stems from a desire to provide legal protection to investigators and sponsors rather than one designed to inform participants/surrogates for rational decision making.14 At present, there is wide agreement that informed consent (including parental permission) requires more than a signature on a form: efforts should be put to promote understanding of consent information.15

The Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review (SIDCER) has recently proposed the ‘enhanced ICF development’ methodology, named ‘SIDCER ICF’, in response to the need for making an ICF complete, concise and understandable.16 The SIDCER ICF methodology has been tested in real informed consent settings involving several clinical trials and it has been shown to be effective in improving participants’ understanding.17 As such, it is compelling to extend the application of the SIDCER ICF methodology to clinical research requiring proxy consent. Therefore, the present study was designed to test the applicability and effectiveness of the SIDCER ICF in paediatric research requiring parental consent. The objective of this study was to compare the parental understanding of information between the parents who read the SIDCER ICF and those who read the conventional ICF.

Materials and methods

This open-label, comparative, randomized-controlled study determined the effectiveness of two different ICFs—the SIDCER ICF and the conventional ICF (1:1)—on parental understanding of research-related information. The study protocol and related documents obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Royal Thai Army Medical Department.

Study participants

Parents of children with transfusion-dependent thalassemia were informed about this ICF study and were recruited by study nurse at the Paediatric Outpatients Department, Phramongkutklao Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. They were invited to read either the SIDCER ICF or the conventional ICF (by random assignment) for possible enrollment of their child (aged 1–18 years) in a drug trial which investigated the effects of furosemide on markers of volume overload in children with transfusion-dependent thalassemia.18 Informed consent was obtained verbally and by action, that is, answering the questionnaire tacitly inferred their consent for participation in this ICF study.

This ICF study planned to enrol 210 parents (with 105 parents in each arm), based on an a priori estimate to detect the hypothesised effect size of 20% difference between two independent proportions of the primary endpoint (p1=0.8 and p2=0.6), with the precision and confidence level of 95%, 80% power and allocation ratio of 1, with a continuity correction. This hypothesised effect size was based on the findings in our previous study.19

Study interventions

The effectiveness of two different ICF interventions on parental understanding were compared: one was the original, standard ICF of the paediatric drug trial (in Thai) and another was the enhanced (SIDCER) ICF of the trial (in Thai). The former comprising six pages with 2065 words was considered as the conventional ICF; trial-related information was described using text in standard sequences. The latter comprising four pages with 1644 words was developed according to the SIDCER ICF methodology, comprehensively described elsewhere.16 In brief, essential information as is relevant to the parents’ decision making was summarised in the SIDCER ICF template (available from http://ijme.in/pdf/appendix-1.pdf?v=1) in a narrative and illustrative manner, according to the SIDCER ICF principles. The drafted SIDCER ICF was, then, reviewed by laypersons to enhance the readability and understandability of written information. Both conventional and SIDCER ICFs contained the same content.

Study outcomes

Parental understanding of essential research-related information was measured using the questionnaire (in Thai), which was modified from our previous studies.17 19 20 It consisted of 24 scenario-based questions which assessed parental understanding of relevant ICF content in the following categories: general items (five questions), patient’s rights (four questions), scientific aspects (eight questions) and ethics aspects (seven questions). Each question with three possible answers was structured in a way that the parents would have had to apply their understanding of information given in an ICF to the scenario.21 In each question, there was only one correct answer, counting as a score of 1, making the highest possible score 24. The primary endpoint was the proportion of parents obtaining the total score of more than 80% (≥20/24). The secondary endpoints were the total score, the score of each category and time spent reading a given ICF and completing the questionnaire.

Study procedure

For allocation of the parents, a computer-generated list of random numbers was applied, and a randomization code was packed in an opaque sealed envelope before subject enrollment to this ICF study. Eligible parents were randomly assigned to read either the SIDCER ICF or the conventional ICF. After that, the questionnaire was distributed. The parents could keep and read the ICF while completing the questionnaire, but they could not ask any questions during this process. Time spent reading the given ICF and completing the questionnaire was recorded and this was the end of the ICF study. The informed consent process continued for the clinical trial for both groups in the same manner, that is, informed consent discussion with the parents was conducted and any inaccurate understanding of trial information was explained prior to the parents’ decision whether or not to sign consent for their child’s participation in the paediatric drug trial.

Patient and public involvement

The present study did not involve patients or publics during the development of research question and outcome measures as well as in the study design and recruitment plan. Patient burden was not assessed formally, but assumed to be low. Results will be disseminated via this publication, with a lay summary of the results in Thai.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the basic features of the data in this study. The proportion of the parents in the SIDCER ICF group who achieved the outcome divided by that of the conventional ICF group was presented using the term ‘relative risk’ (RR). Dichotomous variables were compared using χ2 test. Continuous variables were presented in mean±SD, and the values between the two groups were compared using the Student t-test. Cohen’s d was used to classify the effect size as small (d=0.2), medium (d=0.5) and large (d=0.8).22 Multivariable linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between different ICF interventions and the total score after adjusting for age, gender and education. All statistical analyses were executed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.22.0, with a p value of less than 0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

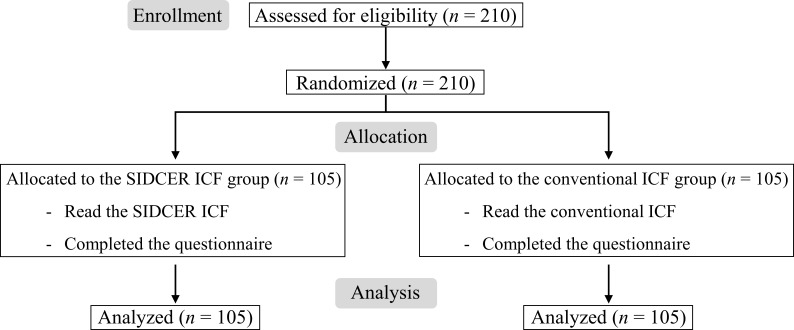

Two hundred and ten parents of thalassemia children were enrolled between September 2015 and September 2016 and equally assigned to the SIDCER ICF group (n=105) and the conventional ICF group (n=105) (figure 1). The mean age of 210 enrolled parents was 35.6±3.1 years; 72.9% were women, and 61.0% had education at a bachelor degree or higher (table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of this ICF study.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the parents (n=210)

| SIDCER ICF (n=105) |

Conventional ICF (n=105) |

|||

| Gender (n) | ||||

| Male | 30 | (28.6%) | 27 | (25.7%) |

| Female | 75 | (71.4%) | 78 | (74.3%) |

| Age (year) | 33.9±12.7 | 37.4±13.3 | ||

| Education (n) | ||||

| High school or below | 49 | (46.7%) | 33 | (31.4%) |

| Bachelor degree or above | 56 | (53.3%) | 72 | (68.6%) |

Data represent the number (percentage) of parents or mean±SD.

The primary endpoint was achieved by 42.9% and 27.6% of the parents in the SIDCER ICF group and the conventional ICF group, respectively (RR=1.552, 95% CI 1.061 to 2.270, p=0.021). The parents in the SIDCER ICF group obtained higher total scores when compared with the conventional ICF group (total score: 18.07±3.71 vs 15.98±4.56, mean difference=2.09, 95% CI 0.96 to 3.22, p=<0.001). After adjustment for age, gender and education, a significant difference in the total score between the two groups was still evident (B=2.75, SE=0.54, beta=0.32, 95% CI 1.69 to 3.81, p<0.001). The values of other secondary endpoints are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Comparisons of the total score, the score in each category of the ICF content and time spent between the two groups

| SIDCER ICF (n=105) |

Conventional ICF (n=105) |

Mean difference | 95% | P value* | Effect size† | |

| Total score (out of 24) | 18.07±3.71 | 15.98±4.56 | 2.09 | (0.96 to 3.22) | <0.001 | 0.49 |

| Score in the general items (out of 5) | 3.99±1.05 | 3.71±1.16 | 0.28 | (-0.03 to 0.58) | 0.072 | 0.25 |

| Score in the patient’s rights (out of 4) | 3.41±0.83 | 3.23±1.07 | 0.18 | (-0.08 to 0.44) | 0.172 | 0.19 |

| Score in the scientific aspects (out of 8) | 5.51±1.70 | 4.50±1.80 | 1.02 | (0.54 to 1.50) | <0.001 | 0.56 |

| Score in the ethics aspects (out of 7) | 5.15±1.52 | 4.54±1.74 | 0.61 | (0.17 to 1.05) | 0.007 | 0.37 |

| Time spent reading a given ICF (minutes) | 23.61±12.51 | 30.90±15.45 | −7.30 | (-11.12 to −3.47) | <0.001 | 0.50 |

| Time spent completing the questionnaire (minutes) | 24.48±12.84 | 30.59±13.29 | −6.11 | (-9.67 to −2.56) | 0.001 | 0.46 |

Data represent mean±SD.

*Student t-test.

†Cohen’s d value.

Proportions of the parents who correctly answered each element of the ICF content were compared between the two groups. The SIDCER ICF was found to be superior to the conventional ICF in improving parental understanding on five elements: who can access the data, right to receive new information, identification of experimental procedures, alternative course of treatment and number of subjects required (table 3). The element that was least understood by the parents in both groups was trial treatment and random assignment; only 66 (out of 210) parents (31.4%) answered this element correctly.

Table 3.

Comparisons of the parental understanding of each element of the ICF content between the two groups

| SIDCER ICF (n=105) |

Conventional ICF (n=105) | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | ||||

| General items | |||||||

| 1. Recognition that this is research | 80 | (76.2%) | 78 | (74.3%) | 1.026 | (0.878–1.198) | 0.749 |

| 2. Subjects’ responsibility | 85 | (81.0%) | 84 | (80.0%) | 1.012 | (0.886–1.156) | 0.862 |

| 3. Confidentiality of records | 74 | (70.5%) | 64 | (61.0%) | 1.156 | (0.950–1.408) | 0.146 |

| 4. Who can access the data | 82 | (78.1%) | 68 | (64.8%) | 1.206 | (1.014–1.435) | 0.032 |

| 5. Research contact persons | 98 | (93.3%) | 96 | (91.4%) | 1.021 | (0.944–1.103) | 0.603 |

| Patient’s rights | |||||||

| 6. Right to refuse | 76 | (72.4%) | 87 | (82.9%) | 0.874 | (0.754–1.012) | 0.069 |

| 7. Right to withdraw | 95 | (90.5%) | 87 | (82.9%) | 1.092 | (0.981–1.215) | 0.104 |

| 8. Consequences of withdrawal | 96 | (91.4%) | 87 | (82.9%) | 1.103 | (0.994–1.225) | 0.064 |

| 9. Right to receive new information | 91 | (86.7%) | 78 | (74.3%) | 1.167 | (1.019–1.336) | 0.024 |

| Scientific aspects | |||||||

| 10. Eligibility of the subject | 81 | (77.1%) | 72 | (68.6%) | 1.125 | (0.953–1.328) | 0.163 |

| 11. Number of subjects required | 87 | (82.9%) | 43 | (41.0%) | 2.023 | (1.583–2.587) | <0.001 |

| 12. Purpose of the study | 80 | (76.2%) | 75 | (71.4%) | 1.067 | (0.908–1.254) | 0.433 |

| 13. Trial treatment and random assignment | 38 | (36.2%) | 28 | (26.7%) | 1.357 | (0.904–2.038) | 0.137 |

| 14. Trial procedures | 65 | (61.9%) | 52 | (49.5%) | 1.250 | (0.979–1.596) | 0.071 |

| 15. Identification of experimental procedures | 80 | (76.2%) | 66 | (62.9%) | 1.212 | (1.011–1.454) | 0.036 |

| 16. Duration of the subject’s participation | 88 | (83.8%) | 79 | (75.2%) | 1.114 | (0.970–1.279) | 0.124 |

| 17. Storage and reuse of human materials | 60 | (57.1%) | 57 | (54.3%) | 1.053 | (0.827–1.340) | 0.677 |

| Ethics aspects | |||||||

| 18. Alternative course of treatment | 94 | (89.5%) | 82 | (78.1%) | 1.146 | (1.016–1.293) | 0.025 |

| 19. Foreseeable risks | 70 | (66.7%) | 61 | (58.1%) | 1.148 | (0.929–1.418) | 0.200 |

| 20. Expected direct/indirect benefits | 52 | (49.5%) | 42 | (40.0%) | 1.238 | (0.914–1.677) | 0.165 |

| 21. Post-trial benefits | 82 | (78.1%) | 72 | (68.6%) | 1.139 | (0.966–1.342) | 0.119 |

| 22. Prorated payment for participation | 91 | (86.7%) | 84 | (80.0%) | 1.083 | (0.959–1.223) | 0.195 |

| 23. Anticipated expenses | 60 | (57.1%) | 53 | (50.5%) | 1.132 | (0.880–1.456) | 0.333 |

| 24. Compensation for injury | 92 | (87.6%) | 83 | (79.0%) | 1.108 | (0.981–1.252) | 0.096 |

Data represent the number (percentage) of parents. *χ2 test.

Discussion

This is the first randomized-controlled study which was designed to test the applicability and effectiveness of the SIDCER ICF methodology in a setting of paediatric drug trials. The SIDCER ICF was found to be superior to the conventional ICF in improving parental understanding of several elements of the ICF content. The overall results of this study are consistent with three previous informed consent studies that exhibited the improvement of participants’ understanding by the SIDCER ICF.17 19 20 In line with a recent integrative review on informed consent, it is reasonable to assume that the evidence of improved participants’ understanding by the SIDCER ICF is largely attributable to its simplicity and concise format with increased processability (using summary boxes, highlights and illustrations, when appropriate).23

Close examination of the data revealed that the SIDCER ICF was superior to the conventional ICF in improving the parental understanding of trial information in five elements: who can access the data, right to receive new information, identification of experimental procedures, alternative course of treatment and number of subjects required. The first three elements were highlighted and made salient in the SIDCER ICF, whereas the same content was ordinarily described in the conventional ICF. It is reasonable to assume that a higher understanding of these three elements in the SIDCER ICF group was partly attributed to a complementary technique being used to convey key information. This might be the evidence to support that increased processability of key or complex information in an ICF could contribute to a significant improvement in parental understanding of such information.23

The element that was least understood by the parents in both groups was trial treatment and random assignment. This finding supports lines of the evidence demonstrating that there is the apparent universality of a limited understanding on the aspect of random allocation of the intervention in clinical trials.24 25 Despite an attempt with increased processability in the SIDCER ICF to aid in description on the concept of randomization (using illustrations and highlights), a large proportion of the parents (63.8%) still did not understand it accurately. This emphasises the need of increased attention in particular during informed consent discussion to ensure adequate understanding of this concept among individuals who consent to a trial.26 A combination of the SIDCER ICF methodology with other means (eg, an integrated cognitive approach) may enhance parental understanding of this information in paediatric research.27

Although the overall results suggested that the SIDCER ICF was superior to the conventional ICF in this setting, the degree of parental understanding remained unsatisfactory. Deficiencies in understanding were still prevalent even among those who read the SIDCER ICF. Moreover, we have noticed that the level of parental understanding in this study is apparently lower than our observations in the previous ICF studies involving other groups of populations.17 19 20 Continued consideration of the normative and practical aspects of informed consent is needed in an attempt to facilitate understanding among parents who act as proxies for their child’s participation in research.28 29 It may be worthwhile to consider using more graphics or pictographs to enhance visualisation of complex information in the SIDCER ICF,30 and further research may be required to determine the effectiveness of such additional means, especially in this group of populations. In addition to the enhanced ICF, a dialogue between the investigator (or a person designated by the investigator) and the parents are still indispensable, while complimentary methods of delivering trial-related information (eg, a multimedia video and website)27 may be warranted in some studies. Furthermore, formal evaluation of parental understanding during the process of informed consent may be necessary, especially in paediatric research that poses relatively high risks, with little or no potential direct benefit, to child subjects.31 32 Accordingly, any inaccuracy of parental understanding could be rectified to ascertain the validity of parental consent obtained in such research.

Of note, this study was confined to parental understanding of an ICF while the child’s understanding of an assent form was not studied. It is also possible that the SIDCER ICF methodology may be modified and used to improve the quality of assent forms for paediatric populations. As such, further ICF studies involving paediatric populations are warranted.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that the SIDCER ICF methodology was applicable to paediatric research requiring parental consent and effective in improving parental understanding of trial information. However, deficiencies in understanding were still prevalent among the parents of child subjects, at least, in this setting, suggesting that further research is required to improve parental understanding in paediatric research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Piyarat Simthamnimit and Dr. Chalinee Monsereenusorn, the investigators of the paediatric drug trial, for their collaboration. Thanks are extended to Ms. Chotimanee Koonrungsesomboon and her colleagues for their assistance in reviewing the SIDCER ICF from laypersons’ perspectives.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was designed by NK and JK, and conducted by CTr and CTi. Data analysis was done by NK. The manuscript was written by NK and revised by JK, with contributions from all authors. All authors approved the final version submitted.

Funding: This study was partially supported by Phramongkutklao Hospital and Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, and TDR, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, co-sponsored by UNICEF, UNDP, the World Bank, and WHO through the Forum for Ethical Review Committees in the Asian and Western Pacific region (FERCAP). The funding sources had no role in the analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Royal Thai Army Medical Department (No. IRB/RTA1200/2557). Informed consent was obtained by action.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Roth-Cline M, Nelson RM. Parental permission and child assent in research on children. Yale J Biol Med 2013;86:291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leibson T, Koren G. Informed consent in pediatric research. Pediatr Drugs 2015;17:5–11. 10.1007/s40272-014-0108-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franck LS, Winter I, Oulton K. The quality of parental consent for research with children: a prospective repeated measure self-report survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2007;44:525–33. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pace C, Talisuna A, Wendler D, et al. Quality of parental consent in a Ugandan malaria study. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1184–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chappuy H, Baruchel A, Leverger G, et al. Parental comprehension and satisfaction in informed consent in paediatric clinical trials: a prospective study on childhood leukaemia. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:800–4. 10.1136/adc.2009.180695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chappuy H, Doz F, Blanche S, et al. Parental consent in paediatric clinical research. Arch Dis Child 2006;91:112–6. 10.1136/adc.2005.076141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chappuy H, Bouazza N, Minard-Colin V, et al. Parental comprehension of the benefits/risks of first-line randomised clinical trials in children with solid tumours: a two-stage cross-sectional interview study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002733 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sugarman J. Examining provisions related to consent in the revised common rule. Am J Bioeth 2017;17:22–6. 10.1080/15265161.2017.1329483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hazen RA, Drotar D, Kodish E. The role of the consent document in informed consent for pediatric leukemia trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:401–8. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berger O, Grønberg BH, Sand K, et al. The length of consent documents in oncological trials is doubled in twenty years. Ann Oncol 2009;20:379–85. 10.1093/annonc/mdn623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kass NE, Chaisson L, Taylor HA, et al. Length and complexity of US and international HIV consent forms from federal HIV network trials. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1324–8. 10.1007/s11606-011-1778-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wen G, Liu X, Huang L, et al. Readability and content assessment of informed consent forms for phase II-IV clinical trials in China. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164251 10.1371/journal.pone.0164251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Villafranca A, Kereliuk S, Hamlin C, et al. The appropriateness of language found in research consent form templates: a computational linguistic analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:30169143 10.1371/journal.pone.0169143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bhutta ZA. Beyond informed consent. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:771–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nishimura A, Carey J, Erwin PJ, et al. Improving understanding in the research informed consent process: a systematic review of 54 interventions tested in randomized control trials. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:28 10.1186/1472-6939-14-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koonrungsesomboon N, Laothavorn J, Chokevivat V, et al. SIDCER informed consent form: principles and a developmental guideline. Indian J Med Ethics 2016;1:83–6. 10.20529/IJME.2016.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koonrungsesomboon N, Tharavanij T, Phiphatpatthamaamphan K, et al. Improved participants' understanding of research information in real settings using the SIDCER informed consent form: a randomized-controlled informed consent study nested with eight clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2017;73:141–9. 10.1007/s00228-016-2159-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simthamnimit P, Traivaree C, Monsereenusorn C, et al. Efficacy of furosemide for prevention of volume overload in children with transfusion-dependent thalassemia at Phramongkutklao Hospital. Royal Thai Army Med J 2015;68:81–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koonrungsesomboon N, Teekachunhatean S, Hanprasertpong N, et al. Improved participants’ understanding in a healthy volunteer study using the SIDCER informed consent form: a randomized-controlled study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016;72:413–21. 10.1007/s00228-015-2000-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koonrungsesomboon N, Traivaree C, Chamnanvanakij S, et al. Improved pregnant women’s understanding of research information by an enhanced informed consent form: a randomised controlled study nested in neonatal research. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018;103:F403–7. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koonrungsesomboon N, Laothavorn J, Karbwang J. Understanding of essential elements required in informed consent form among researchers and institutional review board members. Trop Med Health 2015;43:117–22. 10.2149/tmh.2014-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim H-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: effect size. Restor Dent Endod 2015;40:328–31. 10.5395/rde.2015.40.4.328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Foe G, Larson EL. Reading level and comprehension of research consent forms: an integrative review. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2016;11:31–46. 10.1177/1556264616637483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kupst MJ, Patenaude AF, Walco GA, et al. Clinical trials in pediatric cancer: parental perspectives on informed consent. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2003;25:787–90. 10.1097/00043426-200310000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kodish E, Eder M, Noll RB, et al. Communication of randomization in childhood leukemia trials. JAMA 2004;291:470–5. 10.1001/jama.291.4.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carvalho AA, Costa LR. Mothers' perceptions of their child's enrollment in a randomized clinical trial: poor understanding, vulnerability and contradictory feelings. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:52 10.1186/1472-6939-14-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Antal H, Bunnell HT, McCahan SM, et al. A cognitive approach for design of a multimedia informed consent video and website in pediatric research. J Biomed Inform 2017;66:248–58. 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shilling V, Young B. How do parents experience being asked to enter a child in a randomised controlled trial? BMC Med Ethics 2009;10:1 10.1186/1472-6939-10-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alahmad G. Informed consent in pediatric oncology: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Cancer Control 2018;25 10.1177/1073274818773720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. The effect of format on parents' understanding of the risks and benefits of clinical research: a comparison between text, tables, and graphics. J Health Commun 2010;15:487–501. 10.1080/10810730.2010.492560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wendler D. How to enroll participants in research ethically. JAMA 2011;305:1587–8. 10.1001/jama.2011.421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bromwich D, Rid A. Can informed consent to research be adapted to risk? J Med Ethics 2015;41:521–8. 10.1136/medethics-2013-101912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.