Abstract

Objectives

To detect the combined effects of lifestyle factors on work-related burnout (WB) and to analyse the impact of the number of weekend catch-up sleep hours on burnout risk in a medical workplace.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Hospital-based survey in Taiwan.

Participants

In total, 2746 participants completed the hospital’s Overload Health Control System questionnaire for the period from the first day of January 2016 to the end of December 2016, with a response rate of 70.5%. The voluntary participants included 358 physicians, 1406 nurses, 367 medical technicians and 615 administrative staff.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

All factors that correlated significantly with WB were entered into a multinomial logistic regression after adjustment for other factors. The dose–response relationship of combined lifestyle factors and catch-up sleep hours associated with WB was explored by logistic regression.

Results

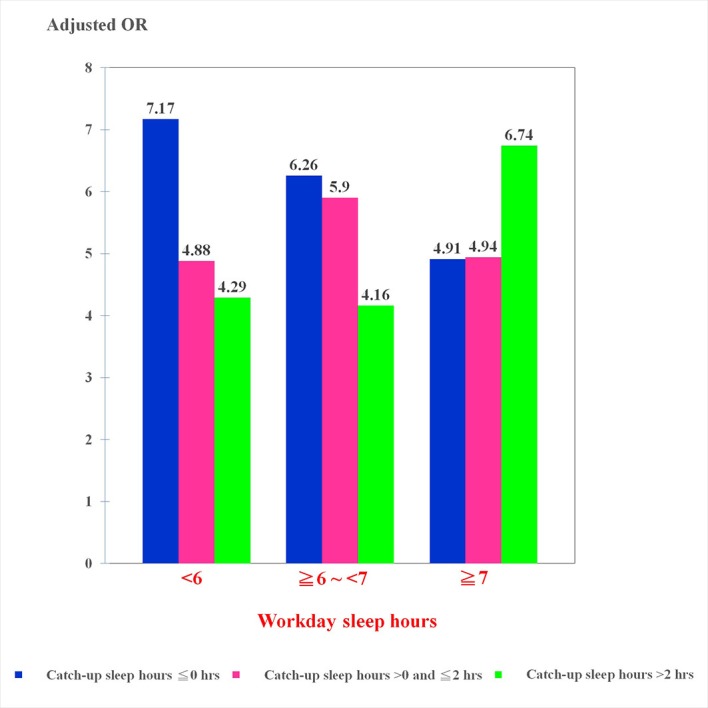

Abnormal meal time (adjusted OR 2.41, 95% CI 1.85 to 3.15), frequently eating out (adjusted OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.97), lack of sleep (adjusted OR 5.13, 95% CI 3.94 to 6.69), no exercise (adjusted OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.81) and >40 work hours (adjusted OR 2.72, 95% CI 2.08–3.57) were independently associated with WB (for high level compared with low level). As the number of risk factors increased (1–5), so did the proportion of high severity of WB (adjusted OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.45 to 4.27, to adjusted OR 32.98, 95% CI 10.78 to 100.87). For those with more than 7 hours’ sleep on workdays, weekend catch-up sleep (≤0/>0 and ≤2/>2 hours) was found to be related to an increase of burnout risk (adjusted OR 4.91, 95% CI 2.24 to 10.75/adjusted OR 4.94, 95% CI 2.54 to 9.63/adjusted OR 6.74, 95% CI 2.94 to 15.46).

Conclusion

WB in the medical workplace was affected by five unhealthy lifestyle factors, and combinations of these factors were associated with greater severity of WB. Weekend catch-up sleep was correlated with lower burnout risk in those with a short workday sleep duration (less than 7 hours). Clinicians should pay particular attention to medical staff with short sleep duration without weekend catch-up sleep.

Keywords: work-related burnout, combined lifestyle factors, weekend catch-up sleep

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to assess the combined effect of unhealthy lifestyle factors on work-related burnout (WB) and to determine the associations between weekend catch-up sleep and WB in the medical workplace.

The modifiable risk factors included in our study were identified according to the contents of a questionnaire based on a legally authorised and official programme and were therefore culturally representative of the local medical workplace.

The study design was cross-sectional, and therefore a causal relationship could not be established.

The associations between weekend catch-up sleep and WB could only be applied to staff experiencing a lack of sleep, because there was no information regarding the number of sleep hours in staff who reported having enough sleep.

Information in this study mainly comprised self-reported measures, and thus information bias may have existed.

Introduction

In recent years, the issue of burnout among employees in the medical profession has received increasing attention, as it can result in a number of deleterious physical, psychological and occupational consequences.1 Previous research has demonstrated that burnout is an important factor when assessing mental health in the workplace.2 Physician burnout is increasingly being recognised as a public health crisis, which is having a range of negative effects on individual physicians, their patients’ care and the healthcare system as a whole.3 Moreover, the prevalence of burnout is greater among residents and fellows than among early career physicians.4 A meta-analytic study revealed that high emotional exhaustion was found in the 31% of the nurses, as well as high depersonalisation and low personal accomplishment in 24% and 38% of the subjects, respectively.5 Compared with other professions (registered nurses and respiratory therapists), physicians and nurse practitioners were more likely to report work–life conflict, irregular work hours and heavy work pressure.6 Another study noted that physician assistants (61.8%) and nurses (66%) had higher prevalence of high work-related burnout (WB) than other medical professions, including physicians (38.6%), administrative staff (36.1%) and medical technicians (31.9%), in a regional hospital in Taiwan.2

Many previous studies have found that certain non-modifiable factors, such as gender, age, marriage status, seniority, job category and shift work, were related to burnout.2 7 The authors of the present study believe that modifiable factors are more important than non-modifiable factors because the former can be improved through on-site health services. A few studies have explored modifiable factors related to workplace burnout, such as higher consumption of fast food, infrequent exercise, long working hours and fewer sleep hours.8–10 However, to date, no research has been conducted to identify the factors most relevant to burnout or to assess the combined effects of these factors.

Several studies have shown that the total number of health-related lifestyle factors has a greater impact on health outcomes (including mortality in cancer patients, disability-free survival and depression) than any single lifestyle factor.11–14 Individual lifestyle behaviours have been associated with elevated burnout level, but to the best of our knowledge, the association between combined lifestyle behaviours and WB in the medical workplace has not been investigated.

One method of coping with insufficient sleep during the workweek is to increase the sleep duration during the weekend.15 Previous studies have demonstrated an association between weekend catch-up sleep and various health outcomes, including obesity, hypertension and health-related quality of life.15–17 However, there are currently no data in the literature on the association between weekend catch-up sleep and WB among medical staff.

Thus, the aims of the present study were (1) to identify modifiable factors associated with WB in the medical workplace and to assess the effects of combined lifestyle factors on WB, and (2) to determine the risk of WB based on the number of weekend catch-up sleep hours in patients with varying degrees of sleep insufficiency during the workweek.

Methods

Participants and study design

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards I and II of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (case number CE18353A). The study design was cross-sectional. The subjects were asked to complete an electronic questionnaire on the Overload Health Control System of Taichung Veterans General Hospital from the first day of January 2016 through the end of December 2016. In total, 2746 participants completed the questionnaire, with a response rate of 70.5% (2746/3894). The voluntary participants included 167 visiting doctors, 191 resident doctors, 1406 nurses, 367 medical technicians and 615 administrative staff (including 16 supervisors). The data were anonymised prior to analysis to protect the subjects’ privacy. Participation in the study did not involve any health risks, and all subjects’ personal data were secured.

Factors in the questionnaire

In Taiwan, the publication ‘Guideline for Preventing Diseases Caused by Exceptional Workload’ was released by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the Ministry of Labor in 2014. According to the guideline, labourers must fill out the overwork assessment questionnaire, which contains items related to sociodemographics (gender, age and marital status), working conditions (current profession, length of employment and self-reported type of work) and lifestyle factors (smoking/alcohol/betel nut use status, sleep condition, meal times, frequency of eating out, exercise habits and self-reported working hours/week). The items in the questionnaire were selected by an expert consensus of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the Ministry of Labour of Taiwan. If participants selected ‘lack of sleep’ or ‘regular physical exercise’ in the questionnaire, they were required to provide their number of sleep hours on workdays and free days, as well as their total duration of weekly exercise. Weekend catch-up sleep hours were calculated according to the following formula: weekend sleep hours−the workday sleep hours.18 Workday sleep duration was categorised into three groups: <6 hours, ≥6 to <7 hours and ≥7 hours. Weekend catch-up sleep duration was categorised into three groups:≤0 hours, >0 to ≤2 hours and >2 hours.

Burnout

The newly developed Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) by Kristensen et al19 is a more straightforward measurement of burnout in medical professionals, as compared with the standard Maslach Burnout Inventory.20 The CBI assesses burnout status through the use of three criteria: personal burnout, WB and client-related burnout. Additionally, a Chinese version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (C-CBI) was constructed based on the CBI, which displayed good validity and reliability.21 22 In this study, we adopted ‘WB’ subscales of the C-CBI to assess burnout risk in the workplace. The C-CBI WB subscales consist of seven items.21 All items used a Likert-type, five-response category scale. The responses were rescaled to a 0–100 metric. According to a previous study,21 the C-CBI WB had a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.87. For WB scores, burnout scores of ≥45 and >60 indicated medium and high burnouts, respectively, in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data from the C-CBI WB subscales were analysed for internal consistency using Cronbach's α. The WB score was categorised into three levels: low, medium and high. Demographic information, working conditions and lifestyle factors were expressed by the category variable and were recorded as numbers (%). Differences in the distribution of categorical variables for WB level were tested using the χ2 test. All factors with significant associations with WB were entered into multinomial logistic regression after adjustment for other factors to calculate the ORs (95% CIs). All calculations were performed using the statistical software programme SPSS V.23, with the level of significance set at p<0.05. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology cross-sectional checklist when writing this report.23

Results

Characteristics of the participants

The demographic information, working conditions and lifestyle factors of the participants are summarised in table 1. Most participants were female (78.55%); 48.83% were married; and 48.73% were single. More than half of the participants were nurses (51.20%) and on day shift (64.64%). Nearly half of the participants were young (between 21 and 34 years old, 47.34%), and around one-third were employed for less than 5 years (34.38%). Most participants denied any smoking/alcohol/betel nut use (98.40%/97.45%/95.41%) and had a normal body mass index (BMI) (68.79%). Analysis of employees’ lifestyle habits revealed abnormal meal times (55.13%), high eating-out rates (93.26% reported eating out for at least one meal per day), lack of sleep (59.07%), non-regular physical exercise (60.74%) and working overtime (>40 hours)(58.56%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (N=2746)

| Factors | n % | Factors | n % |

| Profession | Mealtime | ||

| Doctor (visiting physician) | 167 (6.08) | Normal | 1232 (44.87) |

| Doctor (resident) | 191 (6.96) | Abnormal | 1514 (55.13) |

| Nurse | 1406 (51.20) | Eat out | |

| Medical technician | 367 (13.36) | Zero meal | 185 (6.74) |

| Administrative staff (supervisors) | 16 (0.58) | One meal | 663 (24.14) |

| Administrative staff (other) | 599 (21.81) | Two meals | 832 (30.30) |

| Age (years) | Three meals | 1066 (38.82) | |

| 21–34 | 1300 (47.34) | Lack of sleep | |

| 35–44 | 603 (21.96) | No | 1124 (40.93) |

| 45–54 | 625 (22.76) | Yes | 1622 (59.07) |

| 55–66 | 218 (7.94) | Workday sleep hours <6 hours | |

| Gender | Catch-up sleep hours ≤0 hours | 66 (2.40) | |

| Male | 589 (21.45) | Catch-up sleep hours >0 and ≤2 hours | 243 (8.85) |

| Female | 2157 (78.55) | Catch-up sleep hours >2 hours | 303 (11.03) |

| Length of service (years) | Workday sleep hours ≥6 and <7 hours | ||

| <5 | 944 (34.38) | Catch-up sleep hours ≤0 hours | 115 (4.19) |

| 5–14 | 685 (24.95) | Catch-up sleep hours >0 and ≤2 hours | 452 (16.46) |

| 15–24 | 523 (19.05) | Catch-up sleep hours >2 hours | 211 (7.68) |

| >24 | 443 (16.13) | Workday sleep hours ≥7 hours | |

| Missing | 151 (5.50) | Catch-up sleep hours ≤0 hours | 62 (2.26) |

| Marital status | Catch-up sleep hours >0 and ≤2 hours | 102 (3.71) | |

| Single | 1338 (48.73) | Catch up sleep hours >2 hours | 62 (2.26) |

| Married | 1341 (48.83) | Missing | 6 (0.22) |

| Divorced | 51 (1.86) | Physical exercise | |

| Widowed | 16 (0.58) | None | 1668 (60.74) |

| Body mass index | Regular | 1078 | |

| ≤24 | 1889 (68.79) | <90 min/week | 497 (18.10) |

| >24 | 820 (29.86) | ≥90 and <150 min/week | 289 (10.52) |

| Missing | 37 (1.35) | ≥150 min/week | 281 (10.23) |

| Smoking | Missing | 11 (0.40) | |

| No | 2702 (98.40) | Weekly work hours | |

| Yes | 26 (0.95) | 20–40 | 1131 (41.19) |

| Missing | 18 (0.66) | 41–60 | 1379 (50.22) |

| Betel nut usage | >60 | 229 (8.34) | |

| No | 2676 (97.45) | Missing | 7 (0.25) |

| Yes | 2 (0.07) | Lifestyle factors* | |

| Missing | 68 (2.48) | None | 105 (3.8) |

| Alcohol consumption | One | 369 (13.5) | |

| No | 2620 (95.41) | Two | 593 (21.7) |

| Yes | 126 (4.59) | Three | 736 (26.9) |

| Work type | Four | 734 (26.8) | |

| Day shift | 1775 (64.64) | Five | 202 (7.4) |

| Night shift | 184 (6.70) | ||

| Graveyard shift | 139 (5.06) | ||

| Rotating shift | 648 (23.60) |

*Lifestyle factors: abnormal meal times, frequently eat out, lack of sleep, no exercise, >40 weekly work hours.

Factors associated with WB

The reliability of the WB questionnaire was assessed by Cronbach’s α for each item, with a resulting score of 0.866, indicating a high internal consistency.

Table 2 displays the distribution of WB levels according to sociodemographic, working and lifestyle factors. The percentages of the respondents with a low, medium or high level of WB were 38.71%, 36.64% and 24.65%, respectively. Significantly more women than men (65.6% vs 45.5%, respectively) had a high WB score, that is, medium and high levels of WB. Respondents who were single had higher WB scores than those who were married. The age group of 55–66 years accounted for the lowest percentage among respondents with a high level of WB, whereas the age group of 21–34 years comprised the highest percentage. Among respondents with a medium or high level of WB, those with 15–24 years of employed service constituted the largest percentage (68.9%). With respect to the types of medical professions, nurses had the highest WB scores, while administrative supervisors had the lowest scores. The non-day-shift workers had higher WB scores compared with the day-shift workers. The total number of weekly hours of work was significantly correlated with the WB level.

Table 2.

Distribution of WB levels according to sociodemographics, working and lifestyle factors

| Factors | WB | Total (n=2746) | P value | ||

| Low (n=1063) | Medium (n=1006) | High (n=677) | |||

| Profession | <0.001** | ||||

| Doctor (visiting physician) | 75 (44.9%) | 65 (38.9%) | 27 (16.2%) | 167 (6.1%) | |

| Doctor (resident) | 77 (40.3%) | 65 (34.0%) | 49 (25.7%) | 191 (7.0%) | |

| Nurse | 350 (24.9%) | 568 (40.4%) | 488 (34.7%) | 1406 (51.2%) | |

| Medical technician | 165 (45.0%) | 140 (38.1%) | 62 (16.9%) | 367 (13.4%) | |

| Administrative staff (supervisor) | 14 (87.5%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (6.3%) | 16 (0.6%) | |

| Administrative staff (other) | 382 (63.8%) | 167 (27.9%) | 50 (8.3%) | 599 (21.8%) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001** | ||||

| 21–34 | 458 (35.2%) | 448 (34.5%) | 394 (30.3%) | 1300 (47.3%) | |

| 35–44 | 226 (37.5%) | 240 (39.8%) | 137 (22.7%) | 603 (22.0%) | |

| 45–54 | 246 (39.4%) | 251 (40.2%) | 128 (20.5%) | 625 (22.8%) | |

| 55–66 | 133 (61.0%) | 67 (30.7%) | 18 (8.3%) | 218 (7.9%) | |

| Gender | <0.001** | ||||

| Male | 321 (54.5%) | 181 (30.7%) | 87 (14.8%) | 589 (21.4%) | |

| Female | 742 (34.4%) | 825 (38.2%) | 590 (27.4%) | 2157 (78.6%) | |

| Length of service (years) (n=2595) | <0.001** | ||||

| <5 | 334 (35.4%) | 333 (35.3%) | 277 (29.3%) | 944 (36.4%) | |

| 5–14 | 254 (37.1%) | 258 (37.7%) | 173 (25.3%) | 685 (26.4%) | |

| 15–24 | 163 (31.2%) | 219 (41.9%) | 141 (27.0%) | 523 (20.2%) | |

| >24 | 231 (52.1%) | 154 (34.8%) | 58 (13.1%) | 443 (17.1%) | |

| Marital status | <0.001** | ||||

| Single | 451 (33.7%) | 494 (36.9%) | 393 (29.4%) | 1338 (48.7%) | |

| Married | 581 (43.3%) | 489 (36.5%) | 271 (20.2%) | 1341 (48.8%) | |

| Divorced | 23 (45.1%) | 17 (33.3%) | 11 (21.6%) | 51 (1.9%) | |

| Widowed | 8 (50.0%) | 6 (37.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 16 (0.6%) | |

| Smoking (n=2728) | 0.014* | ||||

| No | 1038 (38.4%) | 991 (36.7%) | 673 (24.9%) | 2702 (99.0%) | |

| Yes | 17 (65.4%) | 7 (26.9%) | 2 (7.7%) | 26 (1.0%) | |

| Betel nut usage (n=2678) | 0.500 | ||||

| No | 1032 (38.6%) | 984 (36.8%) | 660 (24.7%) | 2676 (99.9%) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 2 (0.1%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.558 | ||||

| No | 1011 (38.6%) | 958 (36.6%) | 651 (24.8%) | 2620 (95.4%) | |

| Yes | 52 (41.3%) | 48 (38.1%) | 26 (20.6%) | 126 (4.6%) | |

| Meal time | <0.001** | ||||

| Normal | 677 (55.0%) | 407 (33.0%) | 148 (12.0%) | 1232 (44.9%) | |

| Abnormal | 386 (25.5%) | 599 (39.6%) | 529 (34.9%) | 1514 (55.1%) | |

| Eat out | <0.001** | ||||

| 0–1 meal | 415 (48.9%) | 304 (35.8%) | 129 (15.2%) | 848 (30.9%) | |

| 2–3 meals | 648 (34.1%) | 702 (37.0%) | 548 (28.9%) | 1898 (69.1%) | |

| Lack of sleep | <0.001** | ||||

| No | 677 (60.2%) | 329 (29.3%) | 118 (10.5%) | 1124 (40.9%) | |

| Yes | 386 (23.8%) | 677 (41.7%) | 559 (34.5%) | 1622 (59.1%) | |

| Physical exercise | <0.001** | ||||

| None | 562 (33.7%) | 633 (37.9%) | 473 (28.4%) | 1668 (60.7%) | |

| Regular | 501 (46.5%) | 373 (34.6%) | 204 (18.9%) | 1078 (39.3%) | |

| Body mass index (n=2709) | 0.052 | ||||

| ≤24 | 704 (37.3%) | 700 (37.1%) | 485 (25.7%) | 1889 (69.7%) | |

| >24 | 345 (42.1%) | 288 (35.1%) | 187 (22.8%) | 820 (30.3%) | |

| Weekly work hours (n=2739) | <0.001** | ||||

| 20–40 | 620 (54.8%) | 372 (32.9%) | 139 (12.3%) | 1131 (41.3%) | |

| >40 | 439 (27.3%) | 632 (39.3%) | 537 (33.4%) | 1608 (58.7%) | |

| Work type | <0.001** | ||||

| Day shift | 802 (45.2%) | 636 (35.8%) | 337 (19.0%) | 1775 (64.6%) | |

| Non-day shift | 261 (26.9%) | 370 (38.1%) | 340 (35.0%) | 971 (35.4%) | |

| Lifestyle factors† | <0.001** | ||||

| None | 71 (67.6%) | 30 (28.6%) | 4 (3.8%) | 105 (3.8%) | |

| One | 248 (67.2%) | 99 (26.8%) | 22 (6.0%) | 369 (13.5%) | |

| Two | 321 (54.1%) | 197 (33.2%) | 75 (12.6%) | 593 (21.7%) | |

| Three | 243 (33.0%) | 304 (41.3%) | 189 (25.7%) | 736 (26.9%) | |

| Four | 143 (19.5%) | 297 (40.5%) | 294 (40.1%) | 734 (26.8%) | |

| Five | 33 (16.3%) | 77 (38.1%) | 92 (45.5%) | 202 (7.4%) | |

| Sleep hours (n=2740) | <0.001** | ||||

| No lack of sleep | 677 (60.2%) | 329 (29.3%) | 118 (10.5%) | 1124 (41.0%) | |

| Lack of sleep | |||||

| Workday sleep hours<6 hours | |||||

| Catch-up sleep hours≤0 hours | 13 (19.7%) | 26 (39.4%) | 27 (40.9%) | 66 (2.4%) | |

| Catch-up sleep hours>0 and≤2 hours | 60 (24.7%) | 110 (45.3%) | 73 (30.0%) | 243 (8.9%) | |

| Catch-up sleep hours>2 hours | 88 (29.0%) | 114 (37.6%) | 101 (33.3%) | 303 (11.1%) | |

| Workday sleep hours≥6 and<7 hours | |||||

| Catch-up sleep hours≤0 hours | 22 (19.1%) | 53 (46.1%) | 40 (34.8%) | 115 (4.2%) | |

| Catch-up sleep hours>0 and≤2 hours | 106 (23.5%) | 193 (42.7%) | 153 (33.8%) | 452 (16.5%) | |

| Catch-up sleep hours>2 hours | 53 (25.1%) | 81 (38.4%) | 77 (36.5%) | 211 (7.7%) | |

| Workday sleep hours≥7 hours | |||||

| Catch-up sleep hours≤0 hours | 12 (19.4%) | 24 (38.7%) | 26 (41.9%) | 62 (2.3%) | |

| Catch-up sleep hours>0 and≤2 hours | 18 (17.6%) | 51 (50.0%) | 33 (32.4%) | 102 (3.7%) | |

| Catch-up sleep hours>2 hours | 10 (16.1%) | 24 (38.7%) | 28 (45.2%) | 62 (2.3%) | |

| Exercise per week (n=2735) | <0.001** | ||||

| No physical exercise | 562 (33.7%) | 633 (37.9%) | 473 (28.4%) | 1668 (61.0%) | |

| Regular physical exercise | |||||

| <90 min/week | 224 (45.1%) | 195 (39.2%) | 78 (15.7%) | 497 (18.2%) | |

| ≥90 and<150 min/week | 133 (46.0%) | 86 (29.8%) | 70 (24.2%) | 289 (10.6%) | |

| ≥150 min/week | 135 (48.0%) | 90 (32.0%) | 56 (19.9%) | 281 (10.3%) | |

χ2 test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

†Lifestyle factors: abnormal meal times, frequently eat out, lack of sleep, no exercise, >40 weekly work hours.

Smokers had lower WB scores than non-smokers, but there were no differences in WB scores between alcohol drinkers and non-drinkers or between betel nut users and non-users. There were no significant correlations between WB levels and BMI status. Abnormal meal times, frequently eating out, lack of sleep, no exercise and >40 weekly work hours were positively correlated with WB levels.

Independent factors associated with WB

As detailed in table 3, multinomial logistic regression demonstrated that administrative staff had the lowest risk for WB when compared with nurses (adjusted OR 0.45/0.33, for medium/high level compared with low level). Women had adjusted ORs of 1.41/1.59 for WB (medium/high level compared with low level) when compared with men. The effects of age, length of service and non-day-shift work were non-significant after adjustments.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression of factors associated with WB

| Factors | WB | |||||

| Medium versus low | High versus low | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Gender (male vs female) | 1.41 | (1.08 to 1.85) | 0.013* | 1.59 | (1.11 to 2.29) | 0.012* |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 21–34 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 35–44 | 1.17 | (0.86 to 1.59) | 0.323 | 0.82 | (0.56 to 1.20) | 0.301 |

| 45–54 | 1.23 | (0.76 to 1.98) | 0.403 | 0.74 | (0.41 to 1.34) | 0.322 |

| 55–66 | 1.19 | (0.64 to 2.19) | 0.583 | 0.62 | (0.26 to 1.46) | 0.275 |

| Length of service (years) | ||||||

| <5 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 5–14 | 0.90 | (0.68 to 1.19) | 0.463 | 0.85 | (0.61 to 1.18) | 0.342 |

| 15–24 | 1.21 | (0.77 to 1.89) | 0.404 | 1.64 | (0.95 to 2.82) | 0.074 |

| >24 | 0.95 | (0.56 to 1.61) | 0.856 | 1.02 | (0.51 to 2.02) | 0.960 |

| Profession | ||||||

| Nurse | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Doctor (visiting physician) | 0.63 | (0.39 to 1.00) | 0.052 | 0.47 | (0.26 to 0.87) | 0.015* |

| Doctor (resident) | 0.64 | (0.40 to 1.02) | 0.063 | 0.57 | (0.34 to 0.97) | 0.038* |

| Medical technician | 0.83 | (0.60 to 1.15) | 0.268 | 0.74 | (0.49 to 1.11) | 0.150 |

| Administrative staff (supervisor) | 0.11 | (0.01 to 0.88) | 0.037* | 0.45 | (0.05 to 3.80) | 0.462 |

| Administrative staff (other) | 0.45 | (0.33 to 0.61) | <0.001** | 0.33 | (0.22 to 0.50) | <0.001** |

| Day shift (no vs yes) | 1.04 | (0.81 to 1.34) | 0.753 | 1.18 | (0.88 to 1.57) | 0.268 |

| Lack of sleep | 2.86 | (2.33 to 3.50) | <0.001** | 5.13 | (3.94 to 6.69) | <0.001** |

| No physical exercise | 1.27 | (1.03 to 1.55) | 0.024* | 1.41 | (1.10 to 1.81) | 0.006** |

| Abnormal meal time | 1.47 | (1.19 to 1.82) | <0.001** | 2.41 | (1.85 to 3.15) | <0.001** |

| Often eat out | 1.17 | (0.94 to 1.46) | 0.152 | 1.49 | (1.12 to 1.97) | 0.006** |

| >40 weekly work hours | 1.56 | (1.26 to 1.94) | <0.001** | 2.72 | (2.08 to 3.57) | <0.001** |

| Lifestyle factors†‡ | ||||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||||

| One | 0.91 | (0.54 to 1.52) | 0.717 | 1.39 | (0.45 to 4.27) | 0.564 |

| Two | 1.34 | (0.82 to 2.19) | 0.246 | 3.37 | (1.17 to 9.72) | 0.025* |

| Three | 2.53 | (1.55 to 4.14) | <0.001** | 9.58 | (3.36 to 27.31) | <0.001** |

| Four | 3.95 | (2.37 to 6.58) | <0.001** | 21.73 | (7.58 to 62.31) | <0.001** |

| Five | 4.99 | (2.64 to 9.43) | <0.001** | 32.98 | (10.78 to 100.87) | <0.001** |

| P for trend | <0.001** | <0.001** | ||||

Multinomial logistic regression.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01.

†Adjusted for gender, age, length of service, profession and day shift.

‡Lifestyle factors: abnormal meal time, frequently eat out, lack of sleep, no exercise, >40 weekly work hours.

WB, work-related burnout.

In terms of lifestyle factors, abnormal meal time (adjusted OR 1.47/2.41), frequently eating out (adjusted OR 1.17/1.49), lack of sleep (adjusted OR 2.86/5.13), no exercise (adjusted OR 1.27/1.41) and >40 work hours (adjusted OR 1.56/2.72) were independently associated with WB (for medium/high level compared with low level).

Combined effects of independent lifestyle factors associated with WB

The combined effects of the five independent factors (abnormal meal times, frequently eating out, lack of sleep, no exercise and >40 work hours) are displayed in table 2. As the number of risk factors increases, the proportion of subjects with medium and high levels of WB increases (32.4%, 32.8%, 45.9%, 67.0%, 80.5% and 83.7% for subjects with 0–5 factors, respectively), in a dose–response manner. Table 3 reveals the results of the analysis of the number of lifestyle factors associated with WB by multinomial logistic regression. The adjusted OR (medium level compared with low level) of the participants with 1–5 lifestyle factors were 0.91 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.52), 1.34 (95% CI 0.82 to 2.19), 2.53 (95% CI 1.55 to 4.14), 3.95 (95% CI 2.37 to 6.58) and 4.99 (95% CI 2.64 to 9.43), respectively, compared with those without any factors. The adjusted OR (high level compared with low level) of the participants with 1–5 lifestyle factors were 1.39 (95% CI 0.45 to 4.27), 3.37 (95% CI 1.17 to 9.72), 9.58 (95% CI 3.36 to 27.31), 21.73 (95% CI 7.58 to 62.31) and 32.98 (95% CI 10.78 to 100.87), compared with those without any factors. There was a significant difference in WB (high level compared with low level) among participants with at least two factors, when compared with those without any factors.

Association between weekend catch-up sleep hours and WB

The participants who experienced a lack of sleep were categorised into groups based on their workday sleep hours and weekend catch-up sleep hours. The numbers of each group are shown in table 1. The distribution of WB levels according to the different groups is shown in table 2.

In table 4, the multinomial logistic regression model demonstrates the trends observed in the different groups. In the ‘workday sleep hours <6 hours’ group, those with more weekend catch-up sleep hours had lower WB scores (adjusted OR 7.17/4.88/4.29 for ≤0/>0 and ≤2/>2 hours, compared with those with enough sleep). In the ‘workday sleep hours ≥6 and <7 hours’ group, those with more weekend catch-up sleep hours also had lower WB scores (adjusted OR 6.26/5.90/4.16 for ≤0/>0 and ≤2/>2 hours, compared with those with enough sleep). However, in the ‘workday sleep hours ≥7 hours’ group, those with more catch-up sleep hours had higher WB scores (adjusted OR 4.91/4.94/6.74 for ≤0/>0 and ≤2/>2 hours, compared with those with enough sleep) (figure 1).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis: multinomial logistic regression of sleep hours associated with work-related burnout

| Factors | Multivariate model | |||||

| Medium versus low | High versus low | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Workday and weekend catch-up sleep hours† | ||||||

| No lack of sleep | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Lack of sleep | ||||||

| Workday sleep hours <6 hours | ||||||

| Catch-up sleep hours ≤0 hours | 2.90 | (1.38 to 6.09) | 0.005** | 7.17 | (3.31 to 15.53) | <0.001** |

| Catch-up sleep hours >0 and ≤2 hours | 3.09 | (2.14 to 4.47) | <0.001** | 4.88 | (3.14 to 7.61) | <0.001** |

| Catch-up sleep hours >2 hours | 2.13 | (1.52 to 2.98) | <0.001** | 4.29 | (2.89 to 6.37) | <0.001** |

| Workday sleep hours ≥6 and <7 hours | ||||||

| Catch-up sleep hours ≤0 hours | 3.74 | (2.12 to 6.57) | <0.001** | 6.26 | (3.33 to 11.76) | <0.001** |

| Catch-up sleep hours >0 and ≤2 hours | 3.38 | (2.50 to 4.57) | <0.001** | 5.90 | (4.10 to 8.47) | <0.001** |

| Catch-up sleep hours >2 hours | 2.33 | (1.54 to 3.51) | <0.001** | 4.16 | (2.63 to 6.60) | <0.001** |

| Workday sleep hours ≥7 hours | ||||||

| Catch-up sleep hours ≦0 hours | 2.40 | (1.13 to 5.08) | 0.022* | 4.91 | (2.24 to 10.75) | <0.001** |

| Catch-up sleep hours >0 and ≤2 hours | 3.77 | (2.10 to 6.77) | <0.001** | 4.94 | (2.54 to 9.63) | <0.001** |

| Catch-up sleep hours >2 hours | 2.98 | (1.32 to 6.71) | 0.008** | 6.74 | (2.94 to 15.46) | <0.001** |

| Exercise time per week‡ | ||||||

| No physical exercise | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Regular physical exercise | ||||||

| <90 min/week | 0.96 | (0.74 to 1.26) | 0.786 | 0.62 | (0.44 to 0.89) | 0.008** |

| ≥90 and <150 min/week | 0.72 | (0.52 to 1.01) | 0.057 | 0.85 | (0.58 to 1.25) | 0.413 |

| ≥150 min/week | 0.75 | (0.54 to 1.05) | 0.092 | 0.77 | (0.51 to 1.16) | 0.209 |

Multinomial logistic regression.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

†Adjusted for gender, age, length of service, profession, day shift, exercise, meal time, frequently eat out, work hours

‡Adjusted for gender, age, length of service, profession, day shift, lack of sleep, mealtime, frequently eat out, work hours.

Figure 1.

Work-related burnout risk among participants with different durations of workday sleep and weekend catch-up sleep.

We also attempted to categorise the participants who had regular physical exercise based on the total weekly exercise hours. The numbers for each subgroup and the distribution of WB levels according to the different subgroups are shown in tables 1 and 2. However, there was no dose–response relationship between weekly exercise hours and WB levels after adjustment (table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the combined effect of unhealthy lifestyle factors on WB and to determine the associations between weekend catch-up sleep and WB in the medical workplace. Our findings show that five key modifiable lifestyle factors, including abnormal meal times, often eating out, lack of sleep, no exercise and >40 weekly work hours, were independently associated with WB levels. The number of these combined unhealthy lifestyle factors was shown to be associated with severity of WB in a dose-dependent manner. As the numbers of the above-mentioned lifestyle factors increased, the proportion of respondents with medium or high levels of WB rose. Among these lifestyle factors, a lack of sleep showed the strongest correlation with WB in the medical workplace. In the subgroup analysis of sleep hours, among respondents with duration of workday sleep of less than 7 hours, weekend catch-up sleep was related to reduced burnout risk. However, for those with workday sleep hours greater than 7 hours, weekend catch-up sleep was related to an elevated risk of workplace burnout.

For the non-modifiable factors, our findings are consistent with previous studies which showed that female gender was independently associated with higher burnout levels.2 24 Our study also confirmed the results of a previous study that showed being a nurse was associated with higher burnout levels.2 However, WB in nurses was not significantly different compared with other occupations (except administrative staff) after adjustment. In contrast to other previous studies,2 24 25 length of service and age were not significant risk factors for WB after adjustment in our study. A possible explanation for this is that our results were adjusted for additional lifestyle factors, whereas some previous studies did not control for other variables.2 24

With regard to modifiable factors, our study revealed that obesity was not an independent risk factor for WB, as higher BMI was correlated with lower burnout scores, which was consistent with previous research.26 A possible explanation for this is that hypercortisolism is commonly associated with increased food intake and body weight gain.27 However, burnout was more consistently associated with hypocortisolism,28 which leads to the inhibition of food consumption. In contrast to other studies,29 30 our results found that smokers had lower WB scores compared with non-smokers, while there were no differences in WB scores among alcohol drinkers and betel nut users compared with their abstaining counterparts. This may be due to the sociocultural characteristics of the study population, in which less than 5% of the participants reported smoking, drinking or using betel nuts.31 32

Our analysis of the five key modifiable factors showed that ‘normal meal times’ and ‘infrequent eating out’ were significantly associated with a lower risk of WB. Although no previous studies have directly investigated the relationship between these two factors and burnout, higher levels of fast-food consumption were reported to be positively associated with burnout.10 Moreover, we found that being ‘physically active’ may protect against burnout, as this variable was associated with a low risk of WB, which is consistent with previous studies.8 10 33 34 Burnout prevalence was lower among students who exercised consistently following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations, compared with those who exercised less.8 33 Previous studies did not find a dose–response relationship for exercise hours, which was similar to our findings.25 Additionally, we found that long work hours were a risk factor for higher WB levels. Previous studies also demonstrated that ‘working more than 14 consecutive hours’ and ‘working over 40 hours/week’ were independent risk factors associated with burnout.8 24

Due to the limitations of the official questionnaire used in this study, we surveyed exercise duration per week, general meal times and average number of times eating out per day, without distinguishing between workdays and weekends. Drenowatz et al found that weekend behaviours appeared to be of particular importance, even though overall physical activity levels were similar between weekdays and the weekend.35 A possible explanation is the greater freedom of lifestyle choices during the weekend. Moreover, a nationally representative survey of diet among US adults revealed that weekend consumption was associated with increased calorie intake and poorer diet quality.36 The greater prevalence of fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption may contribute to poorer diet quality on weekends. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that time away from one’s occupation leads to more time spent on food-related activities, and social aspects of weekends are often paired with eating.37 Future research should distinguish the impact of lifestyle habits on workdays and weekends on burnout.

In this study, the strongest correlation with WB was lack of sleep, which was similar to previous studies.9 25 34 Chin et al found that nurses who slept less than 6 hours during the workweek had a higher risk of WB than those who slept more than 7 hours.9 In addition, Wolf and Rosenstock also found that sleeping less than 7 hours was an independent predictor of burnout among medical students.34 Although certain studies have explored the relationship between chronotype/social jetlag and burnout,18 no previous studies have directly investigated the association between weekend catch-up sleep hours and burnout.

Our results revealed that weekend catch-up sleep was correlated with lower burnout risk among subjects with a short workday sleep duration (less than 7 hours). This finding was similar to the results of a previous report by Oh et al,15 who found that among participants with a short workday sleep duration (less than 7 hours), there was a significant difference in health-related quality of life between those with and without weekend catch-up sleep. A possible mechanism underlying this effect could involve the greater sleep debt among participants with short workday sleep durations. Thus, weekend catch-up sleep could compensate for the sleep debt caused by insufficient sleep during the workweek.15However, it was not possible to establish a causal relationship between weekend catch-up sleep and WB in this investigation due to the limitation of the study design.

Our finding revealed that those with ‘workday sleep hours ≥7 hours and catch-up sleep hours >2 hours’ (>9 hours in total on weekends) had higher OR for WB (6.74 compared with those with enough sleep). Generally, around 7–9 hours is regarded as the optimal duration of sleep in terms of psychological well-being and subjectively perceived health.38 Although there is no evidence showing correlations between longer sleep durations and burnout, previous studies have found that long sleep duration (>9 hours) was associated with an increased likelihood of depression, anxiety and diabetes.38 39 A potential underlying mechanism may involve increased levels of inflammation markers in long sleepers.39 Moreover, weekend catch-up sleep behaviour could be considered a violation of sleep hygiene rules.15 Nonetheless, weekend catch-up sleep may reasonably be expected to be associated with better health outcome in subjects with sleep debt, which was indeed borne out by our findings.

Although some studies have investigated the association between combined unhealthy lifestyle factors and risk of depressive symptoms,14 no similar studies have been conducted for burnout. The present report is the first to assess the combined effect of multiple unhealthy lifestyle factors on burnout level. The impact of lifestyle factors on burnout may vary from culture to culture, and thus, we selected lifestyle factors based on items in a questionnaire designed to assess overwork, which was developed by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of Taiwan’s the Ministry of Labour. Finally, only factors that were independently associated with burnout were included in the calculation of the combined effects. Our study has a number of strengths. First, the modifiable risk factors that were selected in our study were based on items in a questionnaire devised by experts for a nationally implemented occupational health programme. Therefore, these factors were both culturally representative and suitable indicators for assessing the local medical workplace. Second, we conducted a stratified analysis of ‘workday sleep hours’ and ‘weekend catch-up sleep hours’, in order to provide an overall risk assessment of weekend catch-up sleep for WB, according to different durations of workday sleep. This study also had several limitations. First, the study design was cross-sectional, and therefore, a causal relationship could not be established. However, it was possible to demonstrate the existence of associations between the modifiable risk factors and WB. Second, there was no information regarding the number of sleep hours of workers who self-reported having enough sleep in this questionnaire. Therefore, our recommendations related to burnout risk of weekend catch-up sleep hours and workday sleep hours can only be applied to staff experiencing a lack of sleep. Third, there was no objective way to assess the quality of sleep or to verify the self-reported sleep duration in this study. In fact, perceived sleep quality may affect self-reported sleep duration, which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results of this study. Fourth, this study is part of a programme that aims to identify medical staff at a high-risk group experiencing burnout. The results, as well as findings from physician interviews, will help to inform the development of a workplace health promotion programme. These measures will inevitably take up part of the weekly working hours and may affect the consistency of the questionnaire. Furthermore, the data obtained in this study largely comprised self-reported information, and thus information bias may have existed. However, the analysis of our questionnaire results yielded a Cronbach α score of 0.866, indicating a high level of reliability.

Conclusion

This study found associations between five modifiable risk factors and WB in a medical workplace in Taiwan and further demonstrated that burnout severity increased in proportion to the number of risk factors. Weekend catch-up sleep was correlated with lower burnout risk in participants with a short workday sleep duration (less than 7 hours) but with higher burnout risk in participants with more than 7 hours’ sleep during the workweek. Clinicians should pay particular attention to people with combined unhealthy lifestyle factors, especially short sleep duration without weekend catch-up sleep. Serious efforts must be undertaken to reduce modifiable risk factors in the workplace to promote the health of medical staff, although further prospective studies are still necessary to establish the causal relationships between unhealthy lifestyle behaviours and burnout.

Patient and public involvement

We developed the research questions and outcome measures based on the official questionnaire released by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in Taiwan. The study was approved by the hospital’s institutional review board (CE18353A), and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the low risk of the study design. All voluntary medical staff completing an electronic questionnaire were enrolled in the study. We will apply the findings of this research to a workplace health promotion programme aimed at improving the health of medical staff.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants, TCVGH-1077202C and TCVGH-1077203D from Taichung Veterans General Hospital for their support, and the Biostatistics Task Force of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, ROC, for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-TT conceived of the study and supervised all aspects of its implementation. Y-LL completed the analyses and drafted the content. Y-SL and S-YH assisted with the study design and revised the content. W-MC, C-HC and Y-CY assisted with the statistical analysis and revised the content. All authors helped to conceptualise ideas, interpret findings and review drafts of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards I and II, Taichung Veterans General Hospital (case number CE18353A).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE, et al. . Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185781 10.1371/journal.pone.0185781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chou L-P, Li C-Y, Hu SC. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004185 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 2018;283:516–29. 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Busireddy KR, Miller JA, Ellison K, et al. . Efficacy of interventions to reduce resident physician burnout: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ 2017;9:294–301. 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00372.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Molina-Praena J, Ramirez-Baena L, Gómez-Urquiza J, et al. . Levels of burnout and risk factors in medical area nurses: a meta-analytic study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2800 10.3390/ijerph15122800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grace MK, VanHeuvelen JS. Occupational variation in burnout among medical staff: evidence for the stress of higher status. Soc Sci Med 2019;232:199–208. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marchand A, Blanc M-E, Beauregard N. Do age and gender contribute to workers’ burnout symptoms? Occup Med 2018;68:405–11. 10.1093/occmed/kqy088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu N-C, Chen J-D, Cheng T-J. The associations between long working hours, physical inactivity, and burnout. J Occup Environ Med 2016;58:514–8. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chin W, Guo YL, Hung Y-J, et al. . Short sleep duration is dose-dependently related to job strain and burnout in nurses: a cross sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:297–306. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alexandrova-Karamanova A, Todorova I, Montgomery A, et al. . Burnout and health behaviors in health professionals from seven European countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2016;89:1059–75. 10.1007/s00420-016-1143-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, et al. . Impact of combined healthy lifestyle factors on survival in an adult general population and in high‐risk groups: prospective results from the Moli‐sani study. J Intern Med 2019. 10.1111/joim.12907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karavasiloglou N, Pestoni G, Wanner M, et al. . Healthy lifestyle is inversely associated with mortality in cancer survivors: results from the third National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES III). PLoS One 2019;14:e0218048 10.1371/journal.pone.0218048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang S, Tomata Y, Discacciati A, et al. . Combined healthy lifestyle behaviors and Disability-Free survival: the Ohsaki cohort 2006 study. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1724–9. 10.1007/s11606-019-05061-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adjibade M, Lemogne C, Julia C, et al. . Prospective association between combined healthy lifestyles and risk of depressive symptoms in the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. J Affect Disord 2018;238:554–62. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oh YH, Kim H, Kong M, et al. . Association between weekend catch-up sleep and health-related quality of life of Korean adults. Medicine 2019;98:e14966 10.1097/MD.0000000000014966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta N, Maranda L, Gupta R. Differences in self-reported weekend catch up sleep between children and adolescents with and without primary hypertension. Clin Hypertens 2018;24 10.1186/s40885-018-0092-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. HJ I, Baek SH, Chu MK, et al. . Association between weekend catch-up sleep and lower body mass: population-based study. Sleep 2017;40 10.1093/sleep/zsx089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheng W-J, Hang L-W. Late chronotype and high social jetlag are associated with burnout in evening-shift workers: Assessment using the Chinese-version MCTQshift. Chronobiol Int 2018;35:910–9. 10.1080/07420528.2018.1439500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, et al. . The Copenhagen burnout inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress 2005;19:192–207. 10.1080/02678370500297720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Winwood PC, Winefield AH. Comparing two measures of burnout among dentists in Australia. Int J Stress Manag 2004;11:282–9. 10.1037/1072-5245.11.3.282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeh W-Y, Cheng Y, Chen C-J, et al. . Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Copenhagen burnout inventory among employees in two companies in Taiwan. Int J Behav Med 2007;14:126–33. 10.1007/BF03000183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yeh WY, Cheng Y, Chen MJ, et al. . Development and validation of an occupational burnout inventory. Taiwan J Public Health 2008;27:349–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12:1495–9. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chambers CNL, Frampton CMA, Barclay M, et al. . Burnout prevalence in New Zealand's public hospital senior medical workforce: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013947 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fernandez Sanchez JC, Perez Marmol JM, Peralta Ramirez MI, et al. . Occupational and life style factors on the levels of burnout in palliative care health professionals. An Sist Sanit Navar 2017;40:421–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Armenta-Hernández O, Maldonado-Macías A, García-Alcaraz J, et al. . Relationship between burnout and body mass index in senior and middle managers from the Mexican manufacturing industry. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:541 10.3390/ijerph15030541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Epel ES, White ML, et al. . Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis dysregulation and cortisol activity in obesity: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;62:301–18. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lennartsson A-K, Sjörs A, Währborg P, et al. . Burnout and Hypocortisolism – A Matter of Severity? A Study on ACTH and Cortisol Responses to Acute Psychosocial Stress. Front. Psychiatry 2015;6 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petrelli F, Scuri S, Tanzi E, et al. . Public health and burnout: a survey on lifestyle changes among workers in the healthcare sector. Acta Biomed 2018;90:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vinnikov D, Dushpanova A, Kodasbaev A, et al. . Occupational burnout and lifestyle in Kazakhstan cardiologists. Arch Public Health 2019;77:13 10.1186/s13690-019-0345-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang MS, Yang MJ, Pan SM. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among clinical nurses in Kaohsiung City. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2001;17:261–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lally RM, Chalmers KI, Johnson J, et al. . Smoking behavior and patient education practices of oncology nurses in six countries. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2008;12:372–9. 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Shanafelt TD. Healthy exercise habits are associated with lower risk of burnout and higher quality of life among U.S. medical students. Academic Medicine 2017;92:1006–11. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wolf MR, Rosenstock JB. Inadequate sleep and exercise associated with burnout and depression among medical students. Acad Psychiatry 2017;41:174–9. 10.1007/s40596-016-0526-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drenowatz C, Gribben N, Wirth MD, et al. . The association of physical activity during weekdays and weekend with body composition in young adults. J Obes 2016;2016:8236439 10.1155/2016/8236439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. An R. Weekend-weekday differences in diet among U.S. adults, 2003–2012. Ann Epidemiol 2016;26:57–65. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jahns L, Conrad Z, Johnson LK, et al. . Diet quality is lower and energy intake is higher on weekends compared with weekdays in midlife women: a 1-year cohort study. J Acad Nutr Diet 2017;117:1080–6. 10.1016/j.jand.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee CHJ, Sibley CG. Sleep duration and psychological well-being among new Zealanders. Sleep Health 2019. 10.1016/j.sleh.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shan Z, Ma H, Xie M, et al. . Sleep duration and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 2015;38:529–37. 10.2337/dc14-2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.