Abstract

Introduction

Mental healthcare is one of the biggest challenges for healthcare systems. Comorbidities between different mental disorders are common, and patients suffer from a high burden of disease. While the effectiveness of collaborative and stepped care models has been shown for single disorders, comorbid mental disorders have rarely been addressed in such care models. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the effectiveness of a collaborative and stepped care model for depressive, anxiety, somatoform and alcohol use disorders within a multiprofessional network compared with treatment as usual.

Methods and analysis

In a cluster-randomised, prospective, parallel-group superiority trial, n=570 patients will be recruited from primary care practices (n=19 practices per group). The intervention is a newly developed collaborative and stepped care model in which patients will be treated using treatment options of various intensities within an integrated network of outpatient general practitioners, psychiatrists, psychotherapists and inpatient institutions. It will be compared with treatment as usual with regard to effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and feasibility, with the primary outcome being a change in mental health-related quality of life from baseline to 6 months. Patients in both groups will undergo an assessment at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months after study inclusion.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the ethics committee of the Hamburg Medical Association (No. PV5595) and will be carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. For dissemination, the results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at conferences. Within the superordinate research project Hamburg Network for Health Services Research, the results will be communicated to relevant stakeholders in mental healthcare.

Trial registration number

Keywords: stepped care, collaborative care, mental disorders, comorbidity, guideline-based healthcare

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, the present randomised controlled trial is the first to investigate the effects of a stepped and collaborative care model, addressing comorbidity by including the most frequent mental disorders (depressive, anxiety, somatoform and alcohol use disorders).

The prospective study design with collecting outcomes at 6 and 12 months follow-up enables us to examine mid-term effects.

Collecting data on healthcare utilisation and cost-relevant data allow a comprehensive health economic evaluation.

The digital systematic screening and diagnosis for mental disorders in both the intervention and control group might potentially limit the intervention’s effect size.

The study will not be able to determine the effectiveness of single diagnostic and therapeutic elements due to its complex intervention model.

Introduction

Background and rationale

Care provision for mental disorders constitutes a substantial challenge in healthcare worldwide. Around 17.6% of the world’s population meets the criteria for a mental disorder during the last 12 months, and about 29.2% experiences a mental disorder at some time in their life.1 The burden of mental disorders (including substance use disorders) has increased to 22.8% of years lived with disability (YLD).2 According to the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2011, there is a substantial gap between the burden caused by mental disorders and the resources available for preventing and treating them. Resources in healthcare systems are inequitably distributed and inefficiently used.3 In high-income countries, 35.5%–50.3% of serious cases received no treatment, while in low-income and middle-income countries, up to 76.3%–85.4% received no treatment.4 The most prevalent mental disorders are depression, anxiety, somatoform and alcohol use disorders.5 Comorbidity of mental disorders is frequent, with 44% of patients having two and 22% having three or more mental conditions simultaneously.6 In addition, there is a significant degree of overlap between the symptoms of these disorders as well as mixed forms,7 8 which calls for comprehensive healthcare approaches for addressing concurrent mental disorders in primary care settings.9

One approach to address comorbidity is collaborative care, an evidence-based form of treatment which focuses on systematically integrating multiprofessional healthcare providers (eg, general practitioners (GPs), specialised mental health professionals).10 11 Systematic reviews have found collaborative care for single mental disorders to be moderately effective12–16 as well as cost-effective17 18 for treating patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders,12 and partly so for treating patients with comorbid physical conditions, for example, diabetes and depression.19

Collaborative care is often combined with stepped care: a guideline-recommended approach by which patients are treated within different intervention steps of varying intensity based on current symptom burden. In this model, patients can be stepped up or down into a more or less intensive treatment, depending on their response to treatment, as assessed by systematic monitoring.20 Stepped care has proven effective for the treatment of depressive symptoms, however, further investigation is required regarding effectiveness for treating other specific disorders, such as somatoform disorders and alcohol-related disorders as well as for comorbid conditions and in order to determine the best manner of delivering this form of care.20–22

Regarding comorbidity, some trials have examined the effects of stepped care on both symptoms of depression and anxiety.12 23 24 A stepped care model for panic and generalised anxiety disorders was found to be effective and cost-effective.13 25 For alcohol use disorders the evidence of the effectiveness of stepped care approaches is limited.26–29 UK-based stepped care approaches were proven to be feasible in primary care with initially higher costs, although probably with greater health benefits in the long term.30 For the development of stepped care models for alcohol use disorders, German guidelines provide recommendations on the assignment of patients to adequate levels of care and respective screening and interventions.31

While there is scarce but promising evidence that collaborative and stepped care might improve the management of somatoform disorders,32 33 these approaches have rarely been implemented and evaluated in practice.34 Somatoform disorders are a frequent phenomenon and are often accompanied by comorbid depression or anxiety disorders.35 Thus, there is a necessity to substantiate an integrated multidisciplinary healthcare approach targeting persistent somatic symptoms, anxiety and depression at the same time.7

The majority of current studies for collaborative and stepped care models for mental disorders do not fully address the needs of primary care in that they only treat one condition or a maximum of two conditions. For example, a systematic review on comorbidity in stepped care approaches found that of 39 studies only 5 studies addressed the comorbidity of mental disorders, and only one study included more than two mental disorders.36

Thus far, research on collaborative and stepped care for mental disorders has been carried out predominantly in the USA.12 However, most healthcare systems outside the USA are structured differently to the USA, which is why US evidence for stepped and collaborative care might not be generalisable to other healthcare systems.37

Taken together, the development of an overarching integrative collaborative and stepped treatment model is necessary for providing evidence and guideline-based treatment for the most common mental disorders (depression, anxiety, somatoform and alcohol use disorders) in primary care, taking into account the comorbidity between these disorders. This treatment approach needs to be examined with regard to effectiveness, cost-effectiveness as well as its barriers and facilitators for implementation into routine practice.9

Objectives

The primary objective of the Collaborative and Stepped Care in Mental Health by Overcoming Treatment Sector Barriers (COMET) study is the effectiveness evaluation of a collaborative and stepped care model (CSC) for patients with depressive, anxiety, somatoform and/or alcohol use disorders. Secondary objectives are the assessment of cost-effectiveness and feasibility of the model. The collaborative and stepped care approach is expected to improve healthcare by optimising the use of existing resources.

The primary hypothesis is that patients treated in CSC will exhibit a greater degree of improvement in mental health-related quality of life 6 months after baseline than patients with treatment as usual (TAU).

Methods and analysis

Study design

The study is a cluster-randomised, prospective, parallel-group, superiority trial comparing the effectiveness of the CSC intervention and TAU with allocation ratio of 1:1 in a consecutive sample of primary care patients with depressive, anxiety, somatoform and/or alcohol use disorders. We selected TAU as the control condition because the research question is to determine whether collaborative and stepped care is superior to usual care. Participants in the TAU group will have unrestricted access to usual care for their mental health problems. GPs in TAU will be instructed to continue treatment with affected patients in the same way as they would outside of the study. Clusters are defined as primary care practices. A cluster randomisation design was chosen, because part of the intervention was an initial training for the GPs to improve their skills and practice visits from the study team to implement study procedures and instruments. We assume that GPs and primary care practices who have been trained and have access to the intervention would no longer be able to treat their patients under control conditions and thus the intervention and control conditions would be mixed. Patients will be assessed at baseline, at months 3 and 6 during treatment and at 12 months follow-up. The study started in February 2017 with a preparation phase. Recruitment and intervention were initiated in July 2018. The primary outcome will be available in February 2020.

Setting

Patients will be recruited in 38 primary care practices (19 TAU and 19 CSC practices) by GPs in Hamburg in Germany. Patients in CSC will be treated in the CSC network by GPs, psychotherapists, psychosomatic specialists and psychiatrists as well as inpatient clinics in Hamburg. The list of all participating care providers can be requested from the study coordinator (Daniela Heddaeus; d.heddaeus@uke.de).

Eligibility criteria

Cluster level (GP practices): inclusion criteria for participation in the study will be to have the approval as a GP in an outpatient practice by the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians of Hamburg. Psychotherapists, psychiatrists and inpatient institutions must have the approval of the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians of Hamburg. All care providers have to sign a cooperation contract in order to participate in the study.

Individual level (patients): inclusion criteria will be a minimum age of 18 years, informed consent and one or more of the following 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) diagnoses, as determined by their GP: depressive episode (F32), recurrent depressive disorder (F33), dysthymia (F34.1), agoraphobia (F40.0), social phobia (F40.1), panic disorder (F41.0), generalised anxiety disorder (F41.1), mixed anxiety and depressive disorder (F41.2), somatoform disorders (F45) and/or mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol (F10). Patients with insufficient knowledge of the German language or a health situation that does not allow questionnaire completion and the participation in telephone interviews as well as patients already receiving current inpatient or outpatient psychopharmacotherapy or psychotherapeutic care will be excluded. Neither somatic nor mental health comorbidities will be exclusion criteria.

Recruitment

Cluster level: primary care practices

In order to recruit participating primary care practices, all State Health Insurance GPs of the city of Hamburg will be informed about the project by mail and invited to an information event where they will be informed about the concept of study, the research aims and study procedures but not given details concerning the intervention itself. Subsequently, they will be asked to participate in the study and to sign a cooperation contract. To increase their willingness to participate, GPs will also be contacted via telephone and, if desired, also receive a personal introduction to the study in their practices. All participating GPs will be visited by the study team to implement study procedures. They will receive detailed patient information materials, informed consent forms, in order to hand them out to the patients, and a tablet computer for the recruitment and screening procedure.

Individual level: patients

Participating GP practices will determine certain days on which recruitment fits in well with their schedule and practice procedures. On these days, each patient entering the practice will be informed about the study. After giving informed consent to participate in a computerised screening procedure, each patient will receive a tablet computer. In line with the recommendations of practice guidelines,31 38–40 the screening procedure consists of selected modules of the German version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-D) (PHQ-9, GAD-7, PHQ-15 and PHQ-Panic module), the Somatic Symptom Disorder-B Criteria Scale (SSD-12) and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). After the screening, the patient hands over the tablet computer to the GP who will discuss the results with the patient. The patient’s screening scores are presented to the doctor, along with the relevance of the score and the cut-off of each test. Screening results may or may not be used by the physician for diagnostic purposes. Integrated ICD-10 diagnostic criteria checklists for the diagnoses under investigation (depressive, anxiety, somatoform and/or alcohol use disorders) support the GP in the selection of the diagnosis. In addition to the selection of the ICD-10 code, the GP indicates the severity of the disorder by classifying it as mild, moderate or severe. If a patient receives one or more of the above-mentioned ICD-10 diagnoses and gives their informed consent, the patient will be included in the study.

Further care providers for the CSC network: psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychosomatic specialists and inpatient institutions

All State Health Insurance psychotherapists, psychiatrists and inpatient institutions in Hamburg will be informed about the project by mail and invited to an informational event at which they will be informed about the study in detail. All psychotherapists, psychosomatic specialists and psychiatrists will receive detailed instruction on the study procedures by phone.

Participant timeline

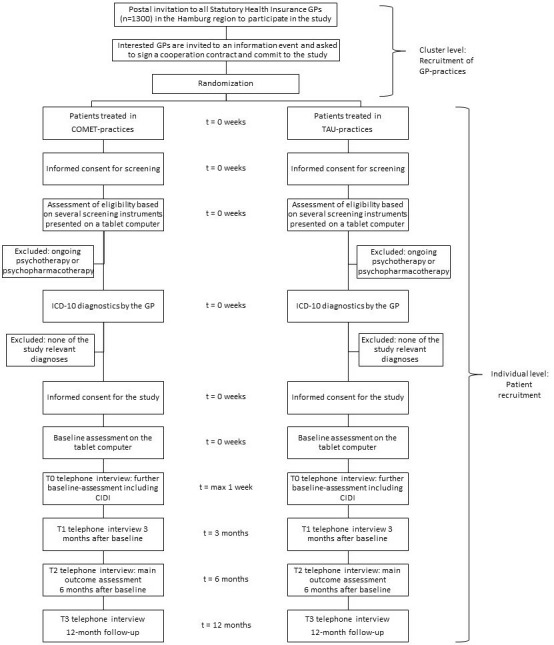

Figure 1 shows the participant timeline.

Figure 1.

Participant timeline. CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; GP, general practitioner; ICD-10, 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; TAU, treatment as usual.

Allocation of treatment and blinding

Cluster randomisation will be performed in order to control for potential bias and increase internal validity. In this study, a cluster randomisation will be performed at the level of GP practices, which will be randomly assigned to CSC and TAU in a ratio of 1:1 and a block length of 4 by a list of computer-generated random numbers without any stratification variables. The randomisation list will be created by a research associate of the Department for Medical Biometry and Epidemiology of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, who is not involved in the implementation of the research project. With the aim to ensure recruiter blinding, the study coordinator, who will not be involved in the recruitment of GPs, will receive the computer-generated randomisation list, preserve it in a place accessible only to her and carry out the allocation of participating GPs. Incoming cooperation contracts will be assigned to CSC versus TAU according to the randomisation list by the study coordinator. GPs will then be informed about their allocation status. Included patients will receive either CSC or TAU depending on their GP’s allocation. This means that even though the allocation is determined by the ranking of the list designed for preventing bias, strictly speaking the allocation is not totally blinded. Blinding of randomisation status cannot be granted for the study team, care providers or patients due to study implementation constraints. Nevertheless, the researchers who perform the statistical analysis will be blinded.

The CSC intervention

The intervention will be a collaborative and stepped care programme provided in the city of Hamburg, Germany by outpatient Statutory Health Insurance GPs, psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychosomatic specialists and inpatient or day-care clinics embedded in the standard healthcare system in Germany. Number of sessions, treatment schedule and the intensity of care will be individually tailored to each patient. The intervention will contain the following elements:

Collaborative network

In contrast to an often-used approach which brings external care managers into GP practices, we will systematically integrate the resources and competencies of cooperating care providers (GPs, psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychosomatic specialists and inpatient facilities), which can more readily create the structures needed to provide a broad spectrum of interventions. Outpatient GPs, psychotherapists, psychosomatic specialists and psychiatrists as well as inpatient or day care facilities will be integrated into the CSC network to enhance the exchange of information about their work in general as well as individual cases of patients and facilitate immediate referral from GPs to specialised care providers. An existing online scheduling platform enables psychotherapists and psychiatrists to indicate available treatment resources and GPs of the network to book those resources. This tool has been developed and successfully implemented in a former project ‘Health network depression’.22 At the beginning of the study, network participants will obtain initial training regarding the evidence-based guidelines of conditions in focus31 38–40 and the planned care model. Additionally, further quality assessment and exchange will be provided in quarterly network meetings.

Computer-assisted and guideline-based diagnosis and treatment decisions

Following the diagnostic process (see ‘Recruitment’ section), each GP will continue with the treatment selection. The algorithm of the software on the tablet computer will provide the GP with one or more treatment recommendations for the individual patient that will be based on guideline recommendations for the diagnosed disorder and its degree of severity.31 38–41 While these recommendations will offer an orientation for therapeutic decisions, the actual treatment decision for one of the evidence-based treatment options will be carried out in cooperation with the patient by integrating individual preferences and needs, thus following the principles of patient-centred care and shared decision-making. Additionally, possible comorbidities and specific characteristics of each of the disorders are to be taken into account.

Collaborative and stepped care interventions

Within the CSC intervention, patients may be offered eight different interventions structured in three steps of varying intensity and setting (table 1). The complex intervention will be delivered by different care providers and increase in intensity.

Table 1.

Guideline-based treatments in the CSC intervention

| Step | Description | Responsible care provider | Setting | |

| 1a | Basic psychosocial care, psychoeducation | Establishment of a working alliance, the provision of psychoeducational materials, psychosocial counselling and treatment of possible comorbid somatic symptoms31 38–40 including systematic monitoring. | GP (or mental health specialist) | Outpatient |

| 1b | Bibliotherapy | Disorder-specific cognitive behavioural therapy-oriented self-help books73–78 accompanied by systematic monitoring. | GP (or mental health specialist) | Outpatient |

| 1c | Internet-based self-management | Internet-based self-help program with a cognitive behavioural therapy-oriented evaluated and certified computer program accompanied by systematic monitoring.79–81 | GP (or mental health specialist) | Outpatient |

| 1d | Single brief interventions (for alcohol use disorders) | Up to five sessions of <1 hour, during which the patient receives individual feedback on alcohol consumption and advice as well as agreed on goals.31 | GP | Outpatient |

| 2a | Psychotherapy | Face-to face cognitive behavioural therapy or psychodynamic psychotherapy either individually or in a group. | Psychotherapist | Outpatient |

| 2b | Pharmacotherapy | Medication according to guideline recommendations. | GP or mental health specialist | Outpatient |

| 3a | Pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy | Intensified combination therapy of psychopharmacotherapy and face-to-face-psychotherapy. | GP or mental health specialist and psychotherapist | Outpatient |

| 3b | Intensified treatment | Intensified treatment carried out by a multiprofessional treatment team. | Multiprofessional team | Day hospital or inpatient facility |

CSC, collaborative and stepped care model; GP, general practitioner.

The materials for step 1 will be provided to the GPs by the study team (ie, psychoeducational materials, self-help books, licenses for the self-help internet programs). For step 1d, the single brief interventions for alcohol use disorders, GPs obtain special training in the context of one of the first network meetings. In case of referral to a specialised care provider in step 2 or 3, the GPs will use the online scheduling platform to book free treatment capacity in the collaboration network. The patient will be instructed to call the booked care provider to confirm the appointment.

Patients will be monitored regularly by their responsible care provider(s) (table 1) with monitoring forms in order to ensure that sufficient treatment response will be achieved and potential undersupply or oversupply will be corrected as quickly as possible. Completed monitoring forms will be sent to the study team.

Previous studies have shown that among patients with mental disorders, those with a high symptom severity in particular do not receive the treatment they need.42–44 It is still unknown whether this is caused by barriers in the referral process, insufficient motivation on the part of the patient or other difficulties. In order to address this problem, case management will be implemented. Based on the digital diagnostic information assessed by the GP during the diagnostic process, a member of the study team will follow the treatment pathways of those patients who are diagnosed with a disorder of a high degree of severity. In those cases, the existing monitoring forms filled out by the care providers will be reviewed, and the responsible care provider will be informed if possible deficiencies in care are detected.

In order to improve the adherence of care providers to the intervention protocol, each provider will receive an initial 3 hours training about the study procedures. Further trainings (also 3 hours each) will cover the guideline recommendation for the four relevant disorders. Additionally, there will be a network meeting for the CSC care providers each quarter. Furthermore, all care providers will obtain detailed instruction manuals, prepared materials and they will be visited in their practice at the beginning as well as in the event that any questions arise or problems occur.

Patients in CSC will be free to use any other additional care, as needed. Other care utilisation will be recorded in data collection interviews (T2 and T3).

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

Following the primary hypothesis that CSC patients will exhibit greater improvement in mental health-related quality of life at 6 months than TAU patients, the primary outcome parameter will be a change in mental health-related quality of life (Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) mental health score)45 from baseline to 6 months.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome parameters will be the change in disorder-specific symptoms as measured using the German versions of the major depressive,46 generalised anxiety,47 panic and somatoform modules of the PHQ,48 the SSD-1249–51 and the AUDIT.52 We will analyse disorder-specific response (at least 50% symptom reduction at 6 months on the disorder-specific screening instruments) and remission (obtaining a value below the respective clinical cut-off value of the disorder-specific screening instruments at 6 months) for these outcome measures. Further secondary outcomes will be health-related quality of life assessed by the SF-36 physical health score, change in health-related quality of life according to the EQ-5D-5L and healthcare utilisation. Table 2 gives an overview of the outcomes.

Table 2.

Outcomes

| Variable | Outcome measure | Outcome | Baseline/T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 |

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Health-related quality of life mental health scale | SF-36 (36 items) | Change in mental health-related quality of life from baseline to 6 months | X | X | X | X |

| Secondary outcome | ||||||

| Disorder-specific symptoms | PHQ-9 (9 items) GAD-7 (7 items) PHQ-15 (15 items) PHQ-Panic module (15 items) SSD-12 (12 items) AUDIT (10 items) |

Change in disorder-specific symptoms from baseline to 6 months | X | X | X | X |

| Response of diagnosed disorder(s) | At least 50% symptom reduction at 6 months on the disorder-specific screening instrument(s) | X | X | X | X | |

| Remission of diagnosed disorder(s) | Obtaining a value below the respective clinical cut-off value of the disorder-specific screening instrument at 6 months | X | X | X | X | |

| Health-related quality of life physical health scale | SF-36 (36 items) | Change in physical health-related quality of life from baseline to 6 months | X | X | X | X |

| Healthcare utilisation | Questionnaire, CSSRI (26 items) | Change in healthcare utilisation at 6 and 12 months | X | X | X | |

| Quality of life | EQ-5D-5L (5 items) | Change in quality of life at 6 and 12 months | X | X | X | |

AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CSSRI, Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire;SF, Short Form Health Survey; SSD, Somatic Symptom Disorder-B Scale.

Economic evaluation

For the calculation of direct and indirect costs healthcare utilisation, reduced productivity at work and work loss days will be measured by a modified version of the Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory (CSSRI).53 The utilisation of inpatient care, outpatient physician services, outpatient non-physician services, medication as well as formal and informal (long-term) care will be assessed. To assess health effects, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) will be calculated based on utilities derived from the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire.

Process evaluation

Additionally, to allow for exploratory analyses, relevant process outcomes will be assessed: implementation, functionality, acceptability and sustainability of the network, including attributes of the healthcare model (eg, relative advantage, compatibility, trialability), adoption/assimilation (eg, needs, motivation, values, preferences, acceptance and skills of involved actors, including patients), communication and influence (diffusion and dissemination, including social networks, opinion leadership, change agents), the context (antecedents and readiness for innovation, incentives, reimbursement regulations) and the implementation process (support and advocacy of implementation process, feedback on progress). For the assessment semi-structured qualitative interviews will be conducted at the beginning and at the end of the study with patients, GPs, psychotherapists, psychosomatic specialists and psychiatrists of the CSC group and the TAU group. We will use semi-structured interview guides on implementation, functionality, acceptance and sustainability of the interventions of the CSC. The interview guides include questions regarding possible beneficial and impeding aspects referring to the implementation process, the care model, adoption/assimilation, communication/impact and context. Questions about the implementation of the study will be integrated in the patient interview at T2. For a separate evaluation of the care process, care providers will be asked at baseline and T3 using standardised short questionnaires. Moreover, process evaluation with care providers will be involved in the quarterly network meetings.

Sample size

We aim for a sample size that permits the detection of a small to moderate standardised mean difference (Cohen’s d=0.35)54; between CSC and TAU for the primary outcome (change in the SF-36 mental health score after 6 months) with a statistical power of 0.80 at a type I error rate of 0.05 (two-sided). Assuming a correlation of 0.50 between baseline and follow-up measurements, this requires analysable data from 95 patients per group (190 in total) for a linear model with the baseline measurement as covariate55 if randomisation takes place at the patient level. With an average cluster size (number of patients per practice) of 12 and an intracluster correlation (ICC) of 0.05, this sample size should be multiplied by a design effect of 1.55,56 leading to 156 patients in 13 practices per group and 312 patients in 26 practices in total. As our experience suggests that up to 30% of the randomised practices and up to 20% of the recruited patients may drop out of the study, we aim to recruit 38 practices (19 per group) including 15 patients each, resulting in a target sample size of 570 recruited patients in total (285 per group).

Data collection methods

Data collection via tablet computer

Data on screening, diagnostics, severity of the disorder, indication and treatment decision as well as the baseline assessment of the primary outcome (SF-36) will be collected on a tablet computer using specially developed web-based screening and diagnostic software (for tests used for the screening, see ‘Recruitment’ section). The software will also ask for reasons for GP consultation, age, gender and whether the patient is already receiving psychotherapy or psychopharmacotherapy at baseline.

Telephone-based patient interviews

The telephone-based patient interviews will take place at four standard measurement points (baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months after baseline, figure 1). All staff members conducting telephone interviews have undergone a special training for the Composite International Diagnostic Interview,57 which is part of the baseline interview, and received detailed guidelines and standard operating procedures for the interviews. In order to conduct the interview, the responsible staff member will call the patient to make an appointment for the interview. At the appointment the staff member will call the patient and carry out the interview. All contact attempts and contacts will be documented. Telephone interviews rather than written questionnaires were chosen to improve the response rate and the quality of the data collected.

The following questionnaires will be used for data assessment:

Short Form Health Survey (primary outcome)

This questionnaire assesses the disease-unspecific, health-related subjective quality of life.45 It comprises eight dimensions (physical functioning, physical role functioning, physical pain, general health perception, vitality, social functioning, emotional role functioning and psychological well-being), which can be assigned to the two main scales ‘physical health’ and ‘mental health’. Answers are Likert scaled. They are weighted, added and transformed to the range 0–100. High values indicate a high health-related quality of life. It is an internationally used, test-theoretically validated instrument with a German reference population.58 The baseline assessment for this instrument is carried out via the tablet computer-based screening after study inclusion in the waiting room of the primary care practice, as described in ‘Monitoring’ section.

Sociodemographic questionnaire

Sociodemographic data will be collected only at baseline assessment and comprise date of birth, gender, country of origin, nationality, parental country of origin, marital status, postal code, educational level, occupation and professional status.

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

This comprehensive interview procedure will be conducted at baseline and consists of 40 modules, which enables the standardised diagnosis of mental disorders (ICD-10, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV)) for the entire lifetime (longitudinal section) or the last 12 months (cross-section). For this study, only the sections for depressive, anxiety, somatoform and alcohol use disorders will be used with regard to the last 12 months.57

PHQ-9, GAD-7, PHQ-15 and PHQ-panic module from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-D)

The baseline assessment for this instrument is carried out via the tablet computer-based screening in the waiting room in the primary care practice, as described in ‘Monitoring’ section. It is the German adaptation of the PHQ, a screening instrument based on the criteria of the DSM-IV, which covers various syndromes and is a practical and well-validated instrument.48 59 60 The following scales and subscales are used in this study:

The PHQ-9 (9 items) for the identification of depressive syndromes covers main and secondary symptoms of depression on a four-step scale according to their frequency.46

The GAD-7 (7 items) to detect generalised anxiety disorder47 and the PHQ panic subscale (15 items) for panic disorder; the GAD-7 is measured on a four-step scale. On the PHQ-panic module, each item corresponds to a DSM-IV panic disorder criterion and is answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’.59

The PHQ-15 (15 items) identifies the somatoform syndrome measured on a three-step scale.

Somatic Symptom Disorder-B Scale

The baseline assessment for this instrument is carried out via the tablet computer-based screening in the waiting room in the primary care practice, as described in ‘Monitoring’ section. It measures the new psychological criteria of the Somatic Symptom Disorder (DSM-5) with 12 items that refer to three subscales to capture cognitive, affective and behavioural aspects. In a first validation study in an outpatient sample, the scale showed very good psychometric properties.51

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

The baseline assessment for this instrument is carried out via the tablet computer-based screening in the waiting room in the primary care practice, as described in ‘Monitoring’ section. The AUDIT is an instrument developed by WHO to identify patients with problematic alcohol consumption in different settings. It is nationally and internationally recognised and includes 10 items related to alcohol consumption, dependence and abuse, with a choice of 3–5 alternatives.52 61

Collaborate

This three-item scale will be assessed at baseline, T2 and T3 to evaluate the shared decision-making process. It measures the dimensions explanation of the health issue, elicitation of patient preferences and integration of patient preferences on a 0–9 scale. It evidences concurrent validity with other measures of SDM, good inter-rater reliability and sensitivity to change.62

Quality of life questionnaire EQ-5D-5L

This generic health-related quality of life questionnaire consists of five items that measure current problems on the dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain discomfort and anxiety/depression on five levels. It can be used as a simple health classification system to detect differences in the health status of population groups. Based on the 3125 possible unique health states derived from the EQ-5D-5L, index scores can be assigned through a set of preference valuations of the general population regarding different health states.63 It also contains a visual analogue scale for the general assessment of health-related quality of life, which allows easy comparisons with the general population.

Modified Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory

This is the modified version of a questionnaire for measuring the utilisation of services, which has been adapted to the specifics of the German healthcare system and serves to assess mental healthcare costs. It collects data about employment and income (employment status, occupation, days of incapacity to work, type and amount of social benefits), use of care services (inpatient, outpatient and complementary care) as well as medication (type and name of medication taken, dosage, number and size of medication packs collected from the pharmacy, price). The instrument has proven itself in practical use, as it allows conclusions to be drawn regarding direct and indirect costs, while providing information on the utilisation and medication profiles of patients.53

Illness Perception Questionnaire Brief

This nine-item tool for recording illness perceptions will be used at baseline. Eight items measure the dimensions of perceived consequences of disease, chronicity, perceived personal control and control over treatment, identity, concerns about specific disorders, coherence and emotional representation of said disorders on scales of 0–10. Higher scores reflect a stronger representation of this dimension. The last item serves to identify the three most subjectively relevant causes of the disease in question. The Illness Perception Questionnaire Brief has predictive and discriminatory validity, and change sensitivity was confirmed in a systematic review.64

Questionnaire on the intensity of the general practitioner commitment (F-HaBi)

This questionnaire will be used at baseline, T2 and T3. It measures the utilisation behaviour of primary care patients. It distinguishes patients with close primary care coordination from those who access further care without prior contact to the GP. Nine items indicate whether the patient has a GP, how often the GP is consulted, how/whether the patient uses the GP as a coordinator and patient satisfaction with the GP and the specialists. Answers are given on a five-point scale. Higher values indicate that the patient is more likely to perceive and use the GP as a coordinator.

Health care utilisation and satisfaction with received treatments in the last 3 or 6 months

These items ask for the treatments received in the last 3 or 6 months on a ‘yes/no’ scale and the patient’s satisfaction with the received treatments on a five-point scale.

Questionnaire assessing satisfaction with outpatient care with focus on patient participation (ZAPA)

This four-item questionnaire will be applied at T2 and T3 to measure patient satisfaction in outpatient medical care, taking into account the concept of patient participation. It has a one-dimensional structure. Its brevity makes it suitable for use in studies measuring patient satisfaction in outpatient care settings.65

Process evaluation (quantitative)

These four items will be asked at T2 to evaluate the implementation of the COMET study (information, acceptance, time expenditure, incentives). An open-ended question at the end will offer participants the opportunity to comment on their satisfaction with the study.

Monitoring forms

In CSC, care providers will be instructed to monitor their patients in regular time intervals. Time intervals will depend on the treatment conducted and will be at least once per quarter. The care provider will document the result of the monitoring on a standardised monitoring form that includes items on the frequency of consultations since the last visit, treatment decision at the last visit, realised treatment and reasons for deviations, symptom changes (deterioration, improvement), impairment due to symptoms, new diagnoses, remitted diagnoses, serious adverse events and future treatment plans.

Retention and discontinuation

All care providers will receive financial incentives for those activities that are additional to their usual care. GPs receive expense allowances up to €120 per patient, psychotherapists up to €290 and psychiatrists up to €150 per patient.

Patients will receive a voucher worth €10 for each of the four conducted interviews. Patients will be contacted up to five times for each of the telephone interviews. If the patient is not available even after five attempts, the GP who included the patient in the study will be informed, and the patient will be called again at the next measurement point. Neither termination of the selected treatment nor termination of the relationship to the recruiting GP will be reasons for a subsequent exclusion from the study and participation in further interviews. Only if the patient explicitly wishes to terminate study participation and does not want to take part in interviews anymore, will they be excluded from the study. The data collected up until that time will only be deleted if the patient explicitly insists on this. All drop-outs will be documented on a drop-out form that will include age, gender, drop-out date and reasons for drop-out.

Data management

Data collected with the web-based screening and diagnostic tool on the tablet computer will be entered electronically by the patient and the GP and stored de-identified in an encrypted database on a server of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. The programme will include range checks for data values. Data collected during the telephone interviews will be entered directly into a password-protected uniform data entry mask by the interviewing researcher. The data entry masks will be preprogrammed (with the program EpiData) to ensure valid values and prevent entry errors. Data collected via monitoring forms will be documented by the responsible care providers of the network and sent to the study team. A student assistant will enter the data into a digital data mask. All collected data will be stored in a database on the UKE internal server in a pseudonymous form. All participant files will be maintained in storage for a period of 10 years after completion of the study. The principal investigators and the study team will have access to the cleaned and final data sets. All data sets will be cleared of any identifying participant information and password-protected.

Monitoring

The study will be monitored by an international advisory board that meets once a year to review the study progress. It consists of five international scientists with expertise in the field of healthcare services research in mental health and collaborative and stepped care models. Progress, challenges and possible adjustments will be presented by the study team and discussed with the advisory board. The board is independent from the sponsor. A data monitoring committee will not be established. Data will be monitored by the study coordinator, who has no competing interests.

Adverse events

We define adverse events as any adverse medical or psychological incident experienced by a patient. Adverse events will be documented by the care providers and the study team whenever they occur. Serious adverse events will be reported to the ethics committee and include suicidality, significant burden, severe or permanent disability, prolonged or unplanned hospitalisation, functional impairment, significant hazard or life-threatening conditions. In order to address suicidality, a standard operating procedure was developed.

Statistical methods

The descriptive statistics will be presented by group and for the total sample. The primary analysis will be based on the intention-to-treat population, which includes all practices and patients randomised and included in the study. A linear mixed model for the changes from baseline of SF-36 will be calculated with group (CSC/TAU) and time as fixed effects, practice and patients as random effects, and the baseline value of the SF-36 mental health score as a covariate. The time by group interaction will be tested, and if the interaction is not significant, the interaction will not be included in the model. The coefficient test, comparing the adjusted SF-36 values between the randomised groups, will be performed using the direct maximum likelihood as the statistical estimation procedure, which results in unbiased estimators under the missing-at-random assumption. The contrast between both groups at the 6 months follow-up will be assessed in a confirmatory manner. The analysis will be repeated in the per-protocol population. To investigate the effects of the missing values on the result of the primary analysis, sensitivity analyses will be carried out with different methods for missing value imputation (eg, multiple imputation, last observation carried forward). The secondary end points will be examined in an exploratory manner. For the binary secondary end points, we will conduct a mixed logistic regression, and for the continuous secondary end points we will carry out a linear mixed model. The other model parameters will be set as in the primary end point analysis. The following subgroup analyses are planned: diagnosis, sex, age, socioeconomic status and symptom severity. Adjusted means and ORs, respectively, with their 95% CIs and p values were reported. The two-sided type I error will be set at 0.05. The safety end points will be determined using frequency tables and using mixed logistic regressions to compare the event frequencies, if possible. Interim analyses are not planned. A detailed statistical analysis plan will be prepared and finalised before the start of the analysis. Results will be reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement extended for cluster randomised trials.

Additional analysis

Direct and indirect costs will be calculated from the societal perspective based on healthcare utilisation, reduced productivity at work and work loss days measured by a modified version the CSSRI.53 For the monetary valuation of resources, German standard unit costs will be applied.66 67 Indirect costs will be calculated based on the human capital approach by applying gross income plus non-wage labour costs.68 For assessing health effects, QALYs will be calculated based on utilities (ie, preference-based scores of health-related quality of life measured on a scale from 0=very bad health to 1=perfect health) derived from the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. Costs and effects of CSC will be compared with standard care in incremental analyses. This will be done by calculating incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).69 The ICER is defined as the ratio of the difference in cost and the difference in health effects between intervention and control group. As the ICER is a point estimate which neither considers statistical uncertainty in the data nor the effect of potential confounding variables, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves will be constructed by means of a series of net benefit regressions using different willingness-to-pay margins.70

Process evaluation

Data of the patient survey will be analysed using descriptive statistics (ie, frequencies, means and SD). The qualitative data will be analysed using structuring content analysis, based on the above-mentioned categories of facilitating and inhibiting factors of implementation and sustainability of CSC.71 72 The qualitative interviews will be transcribed and coded using a deductive category system (eg, attributes of the healthcare concept, adoption/assimilation, communication/influence, context and implementation process), which will be further elaborated on inductively.

Patient and public involvement

Research questions and outcome measures where not informed by patients’ priorities, experience or preferences. Patients were not involved in the design of this study. Patients were not involved in the recruitment for and the conducting of the study. The results will be disseminated to the participating care providers by sending them reports about the study results. Patients will evaluate the impact of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Any severe adverse events as well as any protocol changes will be reported to the ethical committee and the advisory board without delay. Written informed consent will be obtained from all patients by their GPs. There are no foreseeable risks for patients participating in the study. The study does not involve any restriction to standard care.

Personal information about participants

Personal information will be collected on the informed consent form, on which the patient provides their name and telephone number. This form also includes a unique patient code. The telephone number is needed to call the patient for the patient interviews. The GP sends the form via fax to the study coordinator. The study coordinator receives the fax digitally on her computer, extracts the patient code, the name of referring GP and the telephone number, sends this information to the study team and saves the fax as a password-protected file to which only the GP has access. The study team contacts the patient without knowing the patient’s name and conducts the interview. If the landline telephone number is given, the interviewer will ask for the person who is taking part in the COMET study. At the end of the interview, the patient will be asked whether they are interested in an incentive in form of a €10 gift coupon. If so, the patient will be asked for their postal address. The address will not be saved but will instead be eliminated immediately after the coupon is sent.

Dissemination policy

The results and findings of the study will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at conferences and congresses. It will be disseminated also by mean of the multiple partnerships within the superordinate project Hamburg Network for Health Services Research. Results will also be relayed to the participating healthcare providers. A completely anonymised data set will be delivered to an appropriate data archive for sharing purposes. No professional writers will be employed.

Conclusion

In line with the primary hypothesis, the intervention condition is expected to be superior to the control condition. This means that CSC is expected to provide more effective treatment than routine care in terms of improving health-related quality of life 6 months after treatment initiation. In addition, CSC is expected to outperform standard care in secondary outcomes, cost-effectiveness and process variables. A significant contribution to the knowledge relating to whether it is possible and effective to treat a wide range of mental disorders (depression, anxiety, somatoform and alcohol-related disorders) within a collaborative and stepped care model based on evidence-based recommendations is expected. This is a challenge for the care providers and the whole network. Particular interest will be given to how the central issue of comorbidity is dealt with. As far as we know, this is the first randomised controlled study dealing with complex comorbidity patterns.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MH, BL, OvdK, MS, IS, H-HK, KW and DH designed the study and obtained funding. MH, JD and DH are responsible for its conduct and overall supervision. H-HK, CB, TG, KW and AD contributed to specific methodical and health economic issues. DH, JD, SP, KM, SW, AW, TZ, BS, MR and MH worked out study processes, treatment pathways and materials. DH coordinates the study with support from JD and MH. DH, SP, KM and SW organise the network and carry out the recruitment process, network meetings and data collection. DH is responsible for data management. DH, JD and MH wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under the grant number 01GY1602. The sponsor does not have any influence on study design, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, writing or publication process.

Disclaimer: The sponsor does not have any influence on study design, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, writing or publication process.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee of the Hamburg Medical Association approved the study design and intervention (No. PV5595) in September 2017, prior to commencing recruitment. The study will be carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: There are no data in this work.

References

- 1. Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:476–93. 10.1093/ije/dyu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from disease control priorities, 3rd edition. The Lancet 2016;387:1672–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00390-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO Mental health atlas 2011. Italy: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the world Health organization world mental health surveys. JAMA 2004;291:2581–90. 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roca M, Gili M, Garcia-Garcia M, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity of common mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord 2009;119:52–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacobi F, Höfler M, Siegert J, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: the mental health module of the German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1-MH). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2014;23:304–19. 10.1002/mpr.1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008;30:191–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanel G, Henningsen P, Herzog W, et al. Depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders: vague or distinct categories in primary care? results from a large cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res 2009;67:189–97. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gunn J. Designing care for people with mixed mental and physical multimorbidity. BMJ 2015;350:h712 10.1136/bmj.h712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Population-Based care of depression: effective disease management strategies to decrease prevalence. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1997;19:169–78. 10.1016/S0163-8343(97)00016-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:525–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;26 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muntingh A, van der Feltz-Cornelis C, van Marwijk H, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative stepped care for anxiety disorders in primary care: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2014;83:37–44. 10.1159/000353682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, et al. Treatment costs, cost offset, and cost-effectiveness of collaborative management of depression. Psychosom Med 1998;60:143–9. 10.1097/00006842-199803000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zimmermann T, Puschmann E, van den Bussche H, et al. Collaborative nurse-led self-management support for primary care patients with anxiety, depressive or somatic symptoms: cluster-randomised controlled trial (findings of the Smads study). Int J Nurs Stud 2016;63:101–11. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sighinolfi C, Nespeca C, Menchetti M, et al. Collaborative care for depression in European countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2014;77:247–63. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grochtdreis T, Brettschneider C, Wegener A, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of depressive disorders in primary care: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123078 10.1371/journal.pone.0123078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Steenbergen-Weijenburg KM, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Horn EK, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care. A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:19 10.1186/1472-6963-10-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Atlantis E, Fahey P, Foster J. Collaborative care for comorbid depression and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004706 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Firth N, Barkham M, Kellett S. The clinical effectiveness of stepped care systems for depression in working age adults: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2015;170:119–30. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Straten A, Hill J, Richards DA, et al. Stepped care treatment delivery for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2015;45:231–46. 10.1017/S0033291714000701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Härter M, Watzke B, Daubmann A, et al. Guideline-based stepped and collaborative care for patients with depression in a cluster-randomised trial. Sci Rep 2018;8:9389 10.1038/s41598-018-27470-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seekles W, van Straten A, Beekman A, et al. Stepped care treatment for depression and anxiety in primary care. A randomized controlled trial. Trials 2011;12 10.1186/1745-6215-12-171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van't Veer-Tazelaar PJ, van Marwijk HWJ, van Oppen P, et al. Stepped-care prevention of anxiety and depression in late life: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:297–304. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goorden M, Muntingh A, van Marwijk H, et al. Cost utility analysis of a collaborative stepped care intervention for panic and generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. J Psychosom Res 2014;77:57–63. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Drummond C, James D, Coulton S, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening and stepped care interventions for alcohol use disorders in the primary care setting. Cardiff: Welsh Office of Research and Development, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bühringer G, Klein M, Reimer J, et al. S3-Leitlinie screening, diagnose und Behandlung alkoholbezogener Störungen. Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raistrick D. Review of the effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems: national treatment agency for substance misuse 2006.

- 29. Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Stepped care as a heuristic approach to the treatment of alcohol problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:573–9. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Watson JM, Crosby H, Dale VM, et al. AESOPS: a randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of opportunistic screening and stepped care interventions for older hazardous alcohol users in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2013;17:1–158. 10.3310/hta17250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. DG-Sucht S3-Leitlinie "Alkoholbezogene Störungen: Screening, Diagnose und Behandlung": AWMF 2015.

- 32. van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Oppen P, Adèr HJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a collaborative care model with psychiatric consultation for persistent medically unexplained symptoms in general practice. Psychother Psychosom 2006;75:282–9. 10.1159/000093949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shedden-Mora MC, Gross B, Lau K, et al. Collaborative stepped care for somatoform disorders: a pre-post-intervention study in primary care. J Psychosom Res 2016;80:23–30. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murray AM, Toussaint A, Althaus A, et al. The challenge of diagnosing non-specific, functional, and somatoform disorders: a systematic review of barriers to diagnosis in primary care. J Psychosom Res 2016;80:1–10. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kroenke K. Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric comorbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2003;12:34–43. 10.1002/mpr.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maehder K, Löwe B, Härter M, et al. Management of comorbid mental and somatic disorders in stepped care approaches in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract 2019;36:38–52. 10.1093/fampra/cmy122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huijbregts KML, de Jong FJ, van Marwijk HWJ, et al. A target-driven collaborative care model for major depressive disorder is effective in primary care in the Netherlands. A randomized clinical trial from the depression initiative. J Affect Disord 2013;146:328–37. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DGPPN, BÄK, KBV S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare depression. 2. Auflage. 2nd edn Berlin: DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bandelow B, Wiltink J, Alpers GW, et al. Deutsche S3-Leitlinie Behandlung von Angststörungen, 2014. Available: wwwawmforg/leitlinienhtml

- 40. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Sattel H, Ronel J, et al. Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie zum Umgang MIT Patienten MIT nicht-spezifischen, funktionellen und somatoformen Körperbeschwerden: AWMF 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41. Depression N. The treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition). Leicester: The British Psychological Society, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Melchior H, Schulz H, Härter M. Faktencheck Gesundheit: Regionale Unterschiede in Der Diagnostik und Behandlung von Depressionen. Faktencheck Gesundheit. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heddaeus D, Steinmann M, Daubmann A, et al. Treatment selection and treatment initialization in guideline-based stepped and collaborative care for depression. PLoS One 2018;13:e0208882 10.1371/journal.pone.0208882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Katon W, Russo J, Korff M, et al. Long-Term effects of a collaborative care intervention in persistently depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:741–8. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11051.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Löwe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004;42:1194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Zipfel S, et al. Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ-D): manual und Testunterlagen. Karlsruhe: Pfizer, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:345–59. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Löwe B, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians? diagnoses. J Affect Disord 2004;78:131–40. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00237-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Toussaint A, Murray AM, Voigt K, et al. Development and validation of the somatic symptom Disorder–B criteria scale (SSD-12). Psychosom Med 2016;78:5–12. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dybek I, Bischof G, Grothues J, et al. The reliability and validity of the alcohol use disorders identification test (audit) in a German general practice population sample. J Stud Alcohol 2006;67:473–81. 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roick C, Kilian R, Matschinger H, et al. German adaptation of the client sociodemographic and service receipt inventory - an instrument for the cost of mental health care. Psychiat Prax 2001;28:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Accociates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Borm GF, Fransen J, Lemmens WAJG. A simple sample size formula for analysis of covariance in randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:1234–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Donner A. Some aspects of the design and analysis of cluster randomization trials. J Roy Stat Soc C-App 1998;47:95–113. 10.1111/1467-9876.00100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world Health organization (who) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:93–121. 10.1002/mpr.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Radoschewski M, Bellach B-M. Der SF-36 im Bundesgesundheitssurvery - Möglichkeiten und Anforderungen der Nutzung auf Bevölkerungsebene. 61 Gesundheitswesen, 1999: 191–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gräfe K, Zipfel S, Herzog W, et al. Screening psychischer Störungen mit dem “Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ-D)“ Ergebnisse der deutschen Validierungsstudie. Diagnostica 2004;50:171–81. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. primary care evaluation of mental disorders. patient health questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282:1737–44. 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al. The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd edn Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Barr PJ, Thompson R, Walsh T, et al. The psychometric properties of collaborate: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e2 10.2196/jmir.3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ludwig K, Graf von der Schulenburg J-M, Greiner W. German value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics 2018;36:663–74. 10.1007/s40273-018-0615-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Broadbent E, Wilkes C, Koschwanez H, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the brief illness perception questionnaire. Psychol Health 2015;30:1361–85. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1070851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Scholl I, Hölzel L, Härter M, et al. Fragebogen Zur Zufriedenheit in Der ambulanten Versorgung – Schwerpunkt Patientenbeteiligung (ZapA). Klinische Diagnostik und Evaluation 2011;4:50–62. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bock J-O, Brettschneider C, Seidl H, et al. [Calculation of standardised unit costs from a societal perspective for health economic evaluation]. Gesundheitswesen 2015;77:53–61. 10.1055/s-0034-1374621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Grupp H, König H, Konnopka A. Kostensätze Zur monetären Bewertung von Versorgungsleistungen bei psychischen Erkrankungen. Gesundheitswesen 2017;79:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bundesamt S. Earnings and labour costs, 2015. Available: www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/NationalEconomyEnvironment/EarningsLabourCosts/EarningsLabourCosts.html

- 69. Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford university press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Briggs AH, O'Brien BJ, Blackhouse G. Thinking outside the box: recent advances in the analysis and presentation of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness studies. Annu Rev Public Health 2002;23:377–401. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. Hamburg: Beltz Pädagogik, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Makowski AC, Mnich EE, Kofahl C, et al. [psychenet - Hamburg Network for Mental Health: Results of the Process Evaluation]. Psychiat Prax 2015;42:S65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Görlitz G. Self-Help for depression. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rauh E, Rief W. Ratgeber somatoforme Beschwerden und Krankheitsängste. Informationen für Betroffene und Angehörige. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schmidt-Traub S. Angst bewältigen: Selbsthilfe bei Panik und Agoraphobie (5. vollst. überarb. Aufl). Berlin: Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 76. K vC, Stangier U, Phobie RS. Informationen für Betroffene und Angehörige. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Becker ES, Margraf J, Sorgen Vlauter. Hilfe für Betroffene MIT Generalisierter Angststörung (gas) und deren Angehörige. Weinheim: Beltz, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Körkel J. Kontrolliertes Trinken - So reduzieren Sie Ihren Alkoholkonsum. 2 ed. Stuttgart: Trias, 2014: 112. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Meyer B, Bierbrodt J, Schröder J, et al. Effects of an Internet intervention (Deprexis) on severe depression symptoms: randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv 2015;2:48–59. 10.1016/j.invent.2014.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Berger T, Urech A, Krieger T, et al. Effects of a transdiagnostic unguided Internet intervention (‘velibra’) for anxiety disorders in primary care: results of a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2017;47:67–80. 10.1017/S0033291716002270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zill JM, Christalle E, Meyer B, et al. The effectiveness of an Internet intervention aimed at reducing alcohol consumption in adults. Dtsch Arztebl Intl 2019. 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.