Abstract

Objective

The study aim was to test the intra-assessor and interassessor reliability of the Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool (HCAT) for categorising the information in the claim letters in a sample of Danish patient compensation claims.

Design, setting and participants

We used a random sample of 140 compensation cases completed by the Danish Patient Compensation Association that were filed in the field of acute medicine at Danish hospitals from 2007 to 2018. Four assessors were trained in using the HCAT manual before assessing the claim letters independently.

Main outcome measures

Intra-assessor and interassessor reliability was tested at domain, problem category and subcategory levels of the HCAT. We also investigated the reliability of ratings on the level of harm and of the descriptive details contained in the claim letters.

Results

The HCAT was reliable for identifying problem categories, with reliability scores ranging from 0.55 to 0.99. Reliability was lower when coding the ‘severity’ of the problem. Interassessor reliability was generally lower than intra-assessor reliability. The categories of ‘quality’ and ‘safety’ were the least reliable of the seven HCAT problem categories. Reliability at the subcategory level was generally satisfactory, with only a few subcategories having poor reliability. Reliability was at least moderate when coding the stage of care, the complainant and the staff group involved. However, the coding of ‘level of harm’ was found to be unreliable (intrareliability 0.06; inter-reliability 0.29).

Conclusion

Overall, HCAT was found to be a reliable tool for categorising problem types in patient compensation claims.

Keywords: reliability, healthcare complaints, patient safety, Acute care, Health service research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study focuses on injury compensation claims related to emergency hospital care.

A key strength of the study is the testing of the whole Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool (HCAT) instrument (the domains, categories and subcategories) in a large sample of complaint cases outside the setting where HCAT was developed.

Multiple trained raters showed high interassessor reliability.

Due to skewed coverage of the HCAT domains and subcategory levels, our study cannot stand alone and must be followed by further studies in different healthcare settings.

Introduction

Knowledge gained from first-person patient stories can and should be used to improve quality and safety in healthcare.1 In quality improvement research, patients’ perspectives are often collected through custom-made projects with a modest number of participants to explore the experiences of patients and their families within the healthcare system. Such studies provide empirical evidence about the local context, but the heterogeneity of methods used makes learning difficult from a broader perspective.

Most countries have formalised collection of data on patient perspectives, where systems have been established by national authorities and supervising organisations to address patients and relatives’ concerns. These data often benefit from the use of standardised forms completed at the initiative of the patient or relatives. Healthcare organisations and national authorities may receive high volumes of patient complaints and compensation claims, and a main goal is to prevent an incident from happening again.2 3 Such data sources are essential indicators of problems in healthcare systems,4 5 but challenges arise when attempting to use them for quality improvement.6

Although patient complaints and reports of adverse events have been systematically collected for many years, they have typically not been systematically used to assess or improve the quality of healthcare. These sources have great potential to complement other measures of quality such as process performance (eg, initiation of antiplatelet therapy in the management of stroke) and outcomes (eg, mortality and length of stay). Patient complaints and reports of adverse events may provide a more nuanced picture of quality and could help identify potential areas for improvement.

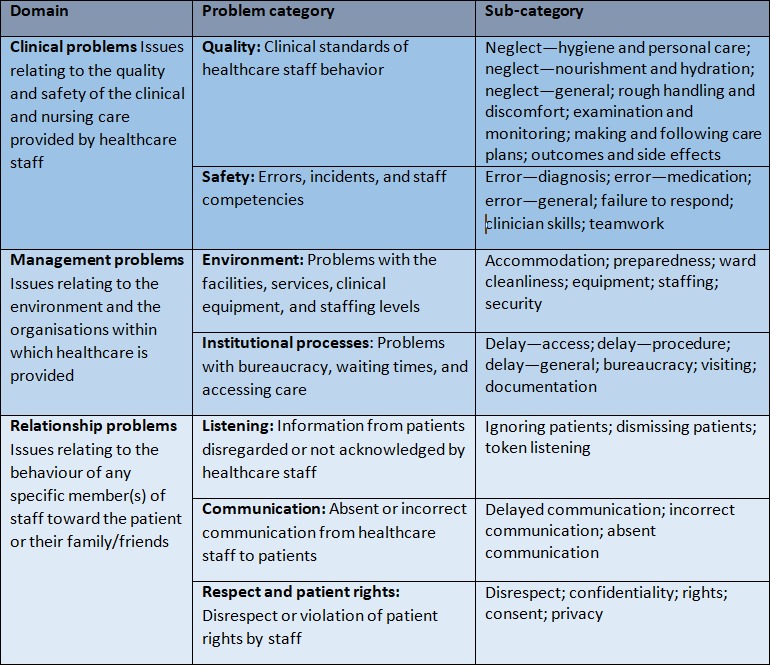

If patient complaints, reports of adverse events and compensation claims are to be used for quality improvement, these data must be aggregated in some way and then analysed in a systematic manner. Reader and colleagues conducted a systematic review of empirical research on patient complaints, aiming to develop a taxonomy for guiding and standardising the analysis of such complaints.7 This review was followed by the development of the Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool (HCAT),8 a standardised tool for systematically codifying and analysing complaints to reliably assess healthcare problems and their severity. The HCAT taxonomy is, to our knowledge, the first tool to be based on a thorough review of the literature and developed with a rigorous and transparent method. The HCAT has been applied in several countries5 9–14 and has been used to identify ‘blind spots’ in healthcare systems.15 The HCAT taxonomy condenses data using a three-level hierarchy of ‘domains’, ‘problem categories’ and 36 subcategories (figure 1). Further, the taxonomy includes data on severity, stage of care, level of harm, the person making a complaint, the gender of the patient and the staff groups to which the complaint refers. The first study on the reliability of HCAT has already been published, while studies testing the reliability of subcategories are in progress.8 Until now, however, reliability testing has only been performed in the UK, and the usefulness of the HCAT needs to be further tested in healthcare systems with different organisational frameworks and different language settings.

Figure 1.

Domains, problem categories and subcategories of the Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool (HCAT) taxonomy (compare Gillespie and Reader8).

The aim of the current study was to test the reliability of the HCAT taxonomy by scoring and analysing patient compensation claims and to clarify the potential of HCAT for quality improvement in a Danish healthcare setting. Reliability coefficients are presented for the three domains, seven problem categories and 36 subcategories of the HCAT.

Methods and materials

Data source and coding form

The compensation and disciplinary systems are separated in the Danish system, and this study only includes compensation claims handled by the Danish Patient Compensation Association (DPCA). We included a random sample of 140 cases completed by the DPCA from 2007 to 2018. Based on previous literature, this sample size should be sufficient.8 15

According to Danish law (the Act on Complaints and Compensations 995/2018), a patient can receive compensation for health expenses, lost earnings, pain and suffering, permanent injury, loss of ability to work and funeral expenses if their injury could have been avoided by an experienced specialist acting differently, and/or if a complication was rarer and more serious than expected for the condition treated. Compensation claims are managed in the DPCA by obtaining all relevant written information (including medical charts, radiographic material and anaesthetic charts) and requisitioning statements from medical and/or surgical specialists. The DPCA then decides whether or not to award compensation to the patient.

To be included in our analysis, the complaint behind the compensation claim must have been provided at a Danish hospital and classified by the DPCA as being within the field of acute medicine. This field is crucial to modern health services16 and in many instances is the patient’s first contact with the secondary health system. Acute care has been continuously reorganised to meet patient expectations. We included only patient claim letters that were drafted by the patient or a relative, thereby emphasising patients’ perspectives on the quality of healthcare. Our sample included both accepted and rejected claims.

Four of the authors acted as assessors (see the Assessors section) and reviewed the claim letters using DPCA’s electronic case management system at the DPCA office in Odense, Denmark. Based on the HCAT manual, a web-based coding form was developed using Research Electronic Data Capture. This was designed to cover all areas addressed by the HCAT and also allowed assessors to note cases where the claims did not fit into the predesigned problem categories. These notes were intended to inform a possible national adoption of the HCAT taxonomy. As instructed in the HCAT manual, assessors read the full claim letter and then completed the web-based form. To be as close as possible to the original HCAT form, the web-based form was in English. As a result, assessors were required to identify Danish keywords while reading the Danish letter and attribute them to English categories.

Patient and public involvement

The public and patients were not involved in the conception or design of this study, nor in the interpretation of the results. Final study results will be shared with stakeholders.

Assessors

Our team of assessors (KPK, JHK, CHH and SFB) consisted of four academics: a student enrolled in a Master of Science in Nursing, a PhD educated general practitioner, a researcher with a Master in Psychology and a researcher with a Master in Public Health Sciences. The assessors were chosen with the expectation that their qualifications would represent potential future users of the HCAT for quality improvements.

The four assessors independently familiarised themselves with the HCAT. This included an introduction to the HCAT manual17 and an online course developed by the inventors of HCAT.8 In a joint session, HCAT was applied to 10 consecutive compensation claims. The first three claims were reviewed and analysed using the HCAT by the group as a whole. For the seven remaining cases, HCAT was applied individually, followed by feedback and discussion within the group. Assessors were trained to adhere as closely as possible to the HCAT manual. Their coding should thus be empirically based and as far as possible free from individual clinical judgements.

After this training, the assessors independently coded the 140 healthcare compensation claims selected for study. To calculate intra-assessor reliability, one assessor scored all cases twice, with 6 weeks between the first and second assessments (and blinded to the scores). The order in which claims were reviewed was randomised between assessors, who were also blinded to each other’s ratings.

Statistics

Linear regression was used to calculate the average number of problem categories per claim letter and the average time spent per claim letter. Regressions used robust SE at case level to account for the heterogeneity in cases. Gwet’s AC1 statistic was used to test intra-assessor and interassessor reliability, for both coding the relevant category (0, 1) and using the severity ratings (0, 1, 2, 3).18 The severity ratings were only applied at the problem category level and were analysed using quadratic weights to assign large discrepancies more weight than small ones. Gwet’s AC1 test was also applied to the reliability testing of stages of care and to the descriptive detail about each compensation case. The level of harm was coded on a scale from 1 (negligible) to 5 (catastrophic) and was treated as a continuous variable; intraclass correlation coefficients (two-way random effects model) were thus used to test reliability. Cases were excluded when three or four assessors found a case to be inapplicable (eg, absence of a patient claim letter or complaints not pertaining to acute medicine).

Our interpretation of reliability followed the commonly used guideline: values 0.01–0.20 denote poor/slight agreement; 0.21–0.40 fair agreement; 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement; and 0.81–1.00 excellent agreement.19 We used Stata V.15 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) for the statistical analyses.

Results

Six cases were found to be ‘not applicable’ by three or four of the assessors and were excluded, leaving 134 cases for analysis. Table 1 shows the distribution of the individual assessors’ coding of the problem categories. On average, assessors applied 1.97 (95% CI 1.85 to 2.09) HCAT categories and spent 4.63 min (95% CI 4.19 to 5.09) per claim letter. We observed a steep learning curve regarding time spent per case, where coding of the last 20 cases took on average 1 min less than coding of the first 20 cases.

Table 1.

The distribution of the individual assessors’ coding of the problem categories

| Assessor 1 | Assessor 2 | Assessor 3 | Assessor 4 | ||

| Round A | Round B | ||||

| Quality | 110 | 87 | 89 | 128 | 135 |

| Safety | 99 | 109 | 86 | 117 | 109 |

| Environment | 2 | 1 | 5 | 14 | 1 |

| Institutional processes | 7 | 11 | 25 | 26 | 32 |

| Listening | 8 | 13 | 19 | 18 | 31 |

| Communication | 3 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 13 |

| Respect | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Not applicable | 13 | 7 | 18 | 15 | 12 |

| Total | 246 | 236 | 255 | 324 | 337 |

Table 2 shows results of the reliability analysis for the three HCAT domains (clinical, management and relationship problems) and the seven problem categories under these, and for information on stage of care, the person making the complaint, the gender of the patient, the staff group involved and the level of harm. Gwet’s AC1 test revealed that the HCAT was reliable in identifying the problem domain, with excellent intra-assessor reliability and substantial to excellent interassessor reliability. The ability of the HCAT to reliably identify problem categories was fair to excellent for both intra-assessor and interassessor reliability. The category of ‘quality’ (clinical standards of healthcare and behaviour) had the poorest intra-assessor reliability (0.55), while the category of ‘safety’ (errors, incidents and staff competencies) had the lowest interassessor reliability (0.61). The reliability for coding the overall ‘stage of care’ category was excellent, but the coding of ‘operation and procedure’ showed the lowest levels of intrareliability and inter-reliability (0.62 and 0.74, respectively). The reliability for coding of complainant, patient gender and involved staff group was excellent, although reliability was only substantial when a claim was related to medical staff (0.65) or the complainant was unspecified (0.66). Both intra-assessor and interassessor reliability were poor when coding ‘level of harm’ (0.4 and 0.19, respectively).

Table 2.

Intrareliability and inter-reliability (n=4) using 134 healthcare compensation claim letters from the DPCA

| HCAT problem categories | Intrareliability | Inter-reliability | ||||

| Agreement | Gwet’s AC | 95% CI | Agreement | Gwet’s AC | 95% CI | |

| Clinical problems | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.89 to 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.93 |

| Quality | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.40 to 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.56 to 0.73 |

| Safety | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.65 to 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.51 to 0.70 |

| Management problems | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.88 to 0.98 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.60 to 0.77 |

| Environment | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.89 to 0.96 |

| Institutional processes | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.88 to 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.64 to 0.81 |

| Relationship problems | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.84 to 0.97 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.62 to 0.80 |

| Listening | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.89 to 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.75 to 0.88 |

| Communication | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.87 to 0.96 |

| Respect and patients’ rights | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 to 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 to 0.99 |

| Stage of care | ||||||

| Admissions | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 to 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.90 to 0.97 |

| Examination and diagnosis | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.58 to 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.59 to 0.77 |

| Care on ward | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.89 to 0.97 |

| Operation or procedure | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.48 to 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.45 to 0.66 |

| Discharge/transfers | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.83 to 0.93 |

| Other stage | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.92 to 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.81 to 0.92 |

| Complainant | ||||||

| Family member | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.94 to 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.90 to 0.98 |

| Patient | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.77 to 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.70 to 0.85 |

| Complainant unspecified | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.84 to 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.74 to 0.87 |

| Patient gender | ||||||

| Female | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.86 to 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.81 to 0.93 |

| Male | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.84 to 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.79 to 0.92 |

| Gender unspecified | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.92 to 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.90 to 0.97 |

| Complained about | ||||||

| Administrative staff | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.92 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 |

| Medical staff | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.71 to 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.56 to 0.75 |

| Nursing staff | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.94 to 0.99 |

| Staff unspecified | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.70 to 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.57 to 0.76 |

| Harm level* | 0.40 | 0.01 to 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.09 ot 0.29 | ||

*Intraclass correlations coefficient.

DPCA, Danish Patient Compensation Association; HCAT, Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool.

The reliability estimates for severity coding (table 3) showed that for the three domains, intra-assessor reliability was excellent and interassessor reliability was substantial to excellent. While six problem categories had excellent intra-assessor reliability and substantial to excellent interassessor reliability, the problem category ‘quality’ had only fair intra-assessor reliability (0.38) and moderate interassessor reliability (0.74).

Table 3.

Case severity: domain and problem intra-assessor and interassessor reliability (n=4) using 134 healthcare claim letters

| HCAT problem categories | Intrareliability | Inter-reliability | ||||

| Agreement | Gwet’s AC1 | 95% CI | Agreement | Gwet’s AC | 95% CI | |

| Clinical problems | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.80 to 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.68 to 0.82 |

| Quality | 0.78 | 0.38 | 0.21 to 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.37 to 0.59 |

| Safety | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.77 to 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.63 to 0.78 |

| Management problems | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.96 to 0.98 |

| Environment | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.93 to 0.98 |

| Institutional processes | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.93 to 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.77 to 0.88 |

| Relationship problems | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.96 to 0.98 |

| Listening | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.95 to 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.85 to 0.93 |

| Communication | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.94 to 0.98 |

| Respect and patients’ rights | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 |

HCAT, Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool.

As shown in table 4, interassessor reliability and intra-assessor reliability were substantial to excellent for most of the 36 HCAT subcategories. The subcategory ‘outcome and side effects’ (under the ‘quality’ category) had significantly poorer intra-assessor reliability (−0.08) than the other subcategories as well as the poorest interassessor reliability (0.33). The subcategory ‘examination & monitoring’ (under the ‘quality’ category) also had poor interassessor reliability (0.41). Twenty-two of the 36 subcategories were used in the intra-assessor reliability testing, and 27 were used in the interassessor reliability testing.

Table 4.

Subcategory intra-assessor and interassessor reliability (n=4) using 134 healthcare claim letters

| Intrareliability | Inter-reliability | |||||

| Agreement | Gwet’s AC | 95% CI | Agreement | Gwet’s AC | 95% CI | |

| Quality | ||||||

| Neglect—hygiene and personal care | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Neglect—nourishment and hydration | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Neglect—general | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.54 to 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.75 to 0.87 |

| Rough handling and discomfort | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.00 |

| Examination and monitoring | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.63 to 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.30 to 0.51 |

| Making and following care plans | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 |

| Outcomes and side effects | 0.45 | −0.08 | −0.26 to 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.33 | 0.22 to 0.43 |

| Other | No ratings | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | ||

| Safety | ||||||

| Error—diagnosis | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.54 to 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.53 | 0.44 to 0.63 |

| Error—medication | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.00 |

| Error—general | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.73 to 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.54 to 0.72 |

| Failure to respond | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Clinician skills | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.76 to 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.77 to 0.89 |

| Teamwork | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.00 |

| Other | No ratings | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.95 to 0.99 | ||

| Environment | ||||||

| Accommodation | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 |

| Preparedness | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Ward cleanliness | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Equipment | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 to 1.00 |

| Staffing | No ratings | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.98 | ||

| Security | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Other | No ratings | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | ||

| Institutional p rocesses | ||||||

| Delay—access | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.93 to 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.93 |

| Delay—procedure | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.89 to 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.80 to 0.90 |

| Delay—general | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 |

| Bureaucracy | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.93 to 0.98 |

| Visiting | No ratings | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | ||

| Documentation | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 |

| Other | No ratings | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | ||

| Listening | ||||||

| Ignoring patients | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.90 to 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.85 to 0.94 |

| Dismissing patients | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.85 to 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.80 to 0.92 |

| Token listening | No ratings | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | ||

| Other | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Communication | ||||||

| Delayed communication | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 |

| Incorrect communication | No ratings | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.98 | ||

| Absent communication | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.98 |

| Other | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Respect and patient rights | ||||||

| Disrespect | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 to 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.95 to 0.99 |

| Confidentiality | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Rights | No ratings | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | ||

| Consent | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Privacy | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

| Other | No ratings | No ratings | ||||

Discussion

Even though the HCAT was developed, tested and refined in a UK setting, it is based on a systematic review of the international literature, which we deem to be the most comprehensive to date.7 This was the main reason for our interest in the HCAT. In this study, we estimated both the intra-assessor and interassessor reliability of the HCAT to investigate its usefulness in settings outside the UK. The four assessors achieved an overall satisfactory level of reliability when using the HCAT on patient claims for compensation. As expected, intra-assessor reliability was superior to its interassessor counterpart in most problem categories. The HCAT was highly reliable when identifying problem categories, but its reliability was lower when coding the severity of problems. However, the reliability of each subcategory was still satisfactory in most cases. The HCAT showed satisfactory reliability when coding information about the complainant and the staff group involved in the complaint, but it was very difficult to code the level of harm incurred, which resulted in low reliability scores. Overall, the HCAT seemed relatively time effective to use; its application took, on average, less than 5 min per compensation claim, and assessors quickly became familiar with the tool.

Interpretation of findings and comparison with existing literature

Our finding that the ‘quality’ and ‘safety’ categories had the lowest reliability corresponds with the findings of Gillespie and Reader who developed the HCAT.8 In their study, substantial reliability was achieved in this domain, but there was still room for improvement. The low reliability in the ‘quality’ category might be because judging quality issues is more subjective than, for example, rating complaints about arrogant behaviour, which are often directly stated in the letter of complaint. Further, some of the subcategories in the quality and safety categories can be difficult to distinguish from each other. For example, the ‘Neglect—general’ subcategory under the ‘Quality’ problem (eg, ‘Infected wound not attended to’) in some instances may tend to largely overlap with the ‘Error—general’ subcategory under ‘safety’. Such ambiguities about the definition of subcategories reduced the interassessor reliability.

Our study achieved reliability estimates for the HCAT problem categories that were comparable to, and in some cases higher than, the estimated reported by Gillespie and Reader.8 It should be noted, however, that the CIs of some of the reliability estimates extended below the level of substantial agreement. Other studies investigating the reliability of the HCAT have reported reliability estimates of 0.75–0.98 at the problem category level11 and reliability coefficients of 0.819 to 0.925 for the HCAT as a whole. No other study has reported on reliability at the subcategory level, and more extensive and robust studies are needed to establish the reliability of the HCAT at this level.

In contrast to the original HCAT reliability study, the level of harm was less reliably scored in our study. This may be due to insufficient training and calibration of raters as the training may have focused more on achieving high agreement on problem categories. However, establishing the extent of harm is a major challenge in compensation claims relative to complaints about disciplinary responsibility with DPCA decisions about damages in practice also being regularly appealed.20 In our analyses, low intra-assessor reliability coefficients tended to appear together with low interassessor reliability, indicating a possible problem in the definition of these categories or in the training of our assessors. The overall high reliability coefficients with few poor to moderate reliability coefficients stress the need to make ongoing calibration and pretraining before it is put into practical use.

We observed a skewed distribution among the seven HCAT problem categories, where most complaints were coded under the ‘quality’ or ‘safety’ categories. The study sample was a random selection of patient compensation claims, and we expect that the observed prevalence of problems reflects the true prevalence in patients’ claims for compensation across the field of acute medicine. While most agreement statistics are only valid with a prevalence of around 50%, Gwet’s AC1 statistic is valid with both high and low prevalences.18 21 The HCAT tool focuses on the identification of macrotrends, which could be difficult to analyse if up to 95% of all claims fall into the ‘quality’ problem category. This emphasises the need for reliable subcategories. Our findings at the subcategory level pointed towards satisfactory reliability but with significant fluctuations in some subcategories.

Strengths and limitations

We focused on compensation claims rather than complaints and thereby tested HCAT against different forms of patient narratives than previously used. We see this as a strength of our study. As our sample represents a narrower spectrum of patient narratives, we anticipated that fewer problem categories would be used, but this only seemed to be the case at the subcategory level.

We followed the HCAT manual as rigorously as possible when we coded the claim letters, and all the assessors followed the tutorial process described by Gillespie and Reader.8 In retrospect, we might have improved the reliability estimates by spending more time becoming familiar with—and agreeing on—the classes of Danish words that indicate specific problem categories. Likewise, the reliability estimates may have benefited from greater discussion among the assessors about how to rate the level of severity. Finally, it remains unclear whether a complete translation of the HCAT into Danish might have resulted in even higher reliability—as this was our first study using the HCAT, we aimed to test the reliability of the original version of the tool. It remains uncertain whether all subcategories of problems can be found in compensation cases.

Conclusion

Our study findings provide support for HCAT as a tool for systematising patient complaints although the applicability and usefulness of the tool needs to be assessed further. Future studies could explore the value of continuous use of HCAT at management level to indicate areas for improvement, detect sites with poor staff–patient communication and investigate how organisational changes affect patient experiences. Our study confirms at least moderate reliability throughout the HCAT taxonomy, except for the rating of level of harm, stage of care and a number of subcategories.

In conclusion, we found that the HCAT performed successfully in a Danish healthcare setting with a different complaint system to the UK. The HCAT was shown to be a reliable tool for distinguishing problem types in patient compensation claim letters and thus has potential for future use in quality research and improvement.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @BieBogh

Contributors: SFB and SBB devised the project with advice from CHH and KM. SBB was the principal investigator and together with SFB was responsible for study design, protocol, data collection and data analysis with input from CHH, KM, JHK and KPJ. The compensation cases were scored by SFB, CHH, JHK and KPJ. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and revising the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Region of Southern Denmark (17/33854).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Danish Data Protection Agency and the DPCA approved our handling of the data (project approval 17/18411). According to Danish law, no approval from an ethics committee was required for this study (Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects (Act 1083, dated 15 September 2017; Para 14)).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Quality safety in health care 2002;11:76–80. 10.1136/qhc.11.1.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friele RD, Sluijs EM. Patient expectations of fair complaint handling in hospitals: empirical data. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:106 10.1186/1472-6963-6-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bouwman R, Bomhoff M, Robben P, et al. . Patients' perspectives on the role of their complaints in the regulatory process. Health Expect 2016;19:483–96. 10.1111/hex.12373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pichert JW, Hickson G, Moore I, et al. . Using Patient Complaints to Promote Patient Safety : Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches (vol 2: culture and redesign. Rockville MD: Advances in Patient Safety, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harrison R, Walton M, Healy J, et al. . Patient complaints about hospital services: applying a complaint taxonomy to analyse and respond to complaints. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:240–5. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Vos MS, Hamming JF, Marang-van de Mheen PJ. The problem with using patient complaints for improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:758–62. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J. Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:678–89. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gillespie A, Reader TW. The healthcare complaints analysis tool: development and reliability testing of a method for service monitoring and organisational learning. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:937–46. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mattarozzi K, Sfrisi F, Caniglia F, et al. . What patients' complaints and praise tell the health practitioner: implications for health care quality. A qualitative research study. Int J Qual Health Care 2017;29:83–9. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bouwman R, Bomhoff M, Robben P, et al. . Classifying Patients’ Complaints for Regulatory Purposes. J Patient Saf 2016:1 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mack JW, Jacobson J, Frank D, et al. . Evaluation of patient and family outpatient complaints as a strategy to prioritize efforts to improve cancer care delivery. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2017;43:498–507. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jerng J-S, Huang S-F, Yu H-Y, et al. . Comparison of complaints to the intensive care units and those to the general wards: an analysis using the healthcare complaint analysis tool in an academic medical center in Taiwan. Crit Care 2018;22 10.1186/s13054-018-2271-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Vos MS, Hamming JF, Chua-Hendriks JJC, et al. . Connecting perspectives on quality and safety: patient-level linkage of incident, adverse event and complaint data. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:180–9. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wallace E, Cronin S, Murphy N, et al. . Characterising patient complaints in out-of-hours general practice: a retrospective cohort study in Ireland. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e860–8. 10.3399/bjgp18X699965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gillespie A, Reader TOMW. Patient-Centered insights: using health care complaints to reveal hot spots and blind spots in quality and safety. Milbank Q 2018;96:530–67. 10.1111/1468-0009.12338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schull MJ, Morrison LJ, Vermeulen M, et al. . Emergency department overcrowding and ambulance transport delays for patients with chest pain. CMAJ 2003;168:277–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gillespie A, Reader TW. Healthcare complaints analysis tool London, United Kingdom: the London school of economics and political science, 2015. Available: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/suppl/2016/01/05/bmjqs-2015-004596.DC1/bmjqs-2015-004596supp_new.pdf

- 18. Gwet KL. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br J Math Stat Psychol 2008;61:29–48. 10.1348/000711006X126600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. STPK Årsberetning 2018 - Ankenævnet for Patienterstatningen. Aarhus: Styrelsen for Patientklager, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Wedding D, et al. . A comparison of Cohen’s Kappa and Gwet’s AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: a study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:61 10.1186/1471-2288-13-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.