Abstract

Objectives

One of the outcomes of a medication review service is to identify and manage medication-related problems (MRPs). The most serious MRPs may result in hospitalisation, which could be preventable if appropriate processes of care were adopted. The aim of this study was to update and adapt a previously published set of clinical indicators for use in assessing the effectiveness of a medication review service tailored to meet the needs of Indigenous people, who experience some of the worst health outcomes of all Australians. i

Design

A modified Delphi technique was used to: (i) identify additional indicators for consideration, (ii) assess whether the original indicators were relevant in the context of Indigenous health and (iii) reach consensus on a final set of indicators. Three rounds of rating were used via an anonymous online survey, with 70% agreement required for indicator inclusion.

Setting

The indicators were designed for use in Indigenous primary care in Australia.

Participants

Thirteen panellists participated including medical specialists, general practice doctors, pharmacists and epidemiologists experienced in working with Indigenous patients.

Results

Panellists rated 101 indicators (45 from the original set and 57 newly identified). Of these, 41 were accepted unchanged, seven were rejected and the remainder were either modified before acceptance or merged with other indicators. A final set of 81 indicators was agreed.

Conclusions

This study provides a set of clinical indicators to be used as a primary outcome measure for medication review services for Indigenous people in Australia and as a prompt for pharmacists and doctors conducting medication reviews.

Trial registration number

The trial registration for the Indigenous Medication Review Service feasibility study is ACTRN12618000188235.

Keywords: Indigenous health, potentially preventable medication-related hospitalisations, medication review, clinical indicators

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first set of clinical indicators developed to identify potentially preventable medication-related hospitalisations in Indigenous Australians;

The set of clinical indicators developed can be used to measure serious medication-related problems in Indigenous Australians and be used as a resource by health professionals conducting medication review services;

The set of clinical indicators forms the primary outcome measure of an Indigenous Medication Review Service feasibility study;

The participant sample size for this study was limited, possibly due to workload constraints of clinicians working in Indigenous health in Australia;

This study makes an important contribution to the literature by developing a quantitative measure that can be used to improve medication outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

Introduction

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia experience higher rates of disease burden compared with other Australians, particularly for chronic disease.1 As pharmacotherapy is one of the principal tools used to manage chronic conditions, this creates a challenge for health services providers to coordinate medication services within a culturally respectful and comprehensive primary healthcare system,2 and minimise medication-related harm. Medication review is a structured evaluation of an individual’s medications to optimise medication use and health outcomes.3 An important component of a medication review involves a pharmacist identifying medication-related problems (MRPs) and, in consultation with the prescriber, suggesting management options.

Medication reviews have been shown to significantly increase the identification and resolution of MRPs, although there is limited evidence to show that they reduce hospital admissions,4 possibly because there are many types of MRPs with varying degrees of severity and preventability.5–7 Although the most serious MRPs can lead to hospitalisation8 some are unpredictable and therefore not considered preventable, for example, atypical adverse drug reactions. However other MRPs are potentially preventable, for example, where clinical care preceding the hospitalisation event is not in accordance with accepted clinical guidelines.

Potentially preventable medication-related hospitalisations (PPMRHs) are the result of a proportion of serious MRPs.8 Clinical indicators have been developed and used in a number of countries to measure PPMRHs which link suboptimal care involving medication use with subsequent hospitalisation.9–11 However, differences have been found, for example, between the UK and USA in terms of the inclusion of particular indicators, presumably guided by the prevalence of different health conditions in different population groups and health system differences.12 Thus, although a set of PPMRH indicators have been developed for use in the Australian population,13 14 it cannot be assumed that this is a robust measure for specific subsets of the Australian population with distinct healthcare needs, like Indigenous people.

There are a number of advantages of using PPMRHs as the primary outcome in a medication review intervention as they: (i) are prespecified, removing potential classification bias from the primary outcome; (ii) can be costed, for easy inclusion in an economic evaluation and (iii) offer a meaningful target for pharmacists and other clinicians undertaking medication reviews in clinical settings.

The Indigenous Medication Review Service (IMeRSe) feasibility study is being undertaken across nine Australian sites including remote, regional and urban locations, with the aim of developing and testing the feasibility of a culturally appropriate, strengths-based, medication review service.15 The IMeRSe intervention is delivered by local community pharmacists (on a fee-for-service basis) integrated with local Aboriginal health services (AHSs). Previous research has shown that Indigenous people encounter barriers to accessing medication review services,16 17 thus the aim of IMeRSe is to overcome these barriers and meet the health needs of the population.15

Here we report on the modification of the existing set of 45 PPMRH indicators which were originally developed for use in the general Australian population and validated using a large veterans cohort.13 14 However, the indicators needed to be revised; to ensure: (i) utility, as an appropriate primary outcome measure in the IMeRSe feasibility study; and (ii) currency and applicability, in light of changes to clinical guidelines and best practice. Inclusion criteria for the IMeRSe study specifies participants to be over 18 years and identify as being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander,15 meaning participants will likely be younger and experience different health conditions than the general Australian population.1 Thus, the list of previously identified PPMRHs needs to be revised to reflect the health problems faced by this population.

The objective of this study was to develop a meaningful and clinically relevant outcome measure for use in the IMeRSe pilot study,15 which is trialling the feasibility of a culturally appropriate, strengths-based, medication review service.

Methods

In general terms, the selection of clinical indicators to measure processes and outcomes of primary care should meet the criteria of validity, reproducibility, acceptability, feasibility, reliability, sensitivity and predictive validity.18 Consensus methods are one way of developing, or refining, a set of clinical indicators to meet these criteria. The Delphi technique has been widely used in health research to achieve consensus on a particular topic where expert opinion is the main source of evidence,19 20 including the development of healthcare quality indicators.21 Other consensus methods, such as the nominal group technique,22 or the RAND appropriateness method,23–26 may also be appropriate; however, the Delphi technique has the advantage of involving a sufficiently representative group of experts while being less resource intensive than alternative methods.

Selection of Delphi panellists

The IMeRSe feasibility study Expert Stakeholder Panel (which included Indigenous advisors) identified potential panellists for the Clinical Validation Group (CVG).15 The function of the Expert Stakeholder Panel is to ensure that all aspects of the study are culturally appropriate and respect Indigenous practices, protocols and community engagement. Potential CVG panellists were identified by the Expert Stakeholder Panel as either having current clinical experience as a doctor or a pharmacist in an Indigenous health setting, or medication safety expertise from a public health perspective. Ideally, Indigenous clinicians and researchers would constitute the whole of the CVG, however while the CVG did have Indigenous representation and attempts were made to include more, we were not able to convene an entirely Indigenous CVG. Potential panellists were approached via email, provided with participant information forms and instructions, and contact details to obtain further information, as required. Panellists were made aware that informed consent was implied by acceptance of the invitation via return email. Of the 40 eligible panellists approached to participate, 13 agreed. Panellists were offered a small honorarium to compensate them for their time.

Rating rounds

Prior to the start of the first rating round, consented panellists were interviewed individually by a member the research team (JS) to ensure they had a chance to clarify the Delphi process. During the interview, panellists were asked to identify any additional indicators that they believed should be considered in addition to the original 45 indicators14 or email them after the interview, if preferred. Panellists were asked to only identify indicators that met the criteria of preventable drug-related morbidity, as defined by Hepler & Strand27 who specify three necessary elements:

The drug-related problem must be recognisable, and the likelihood of an undesirable clinical outcome must be foreseeable;

The causes of that outcome must be identifiable;

The causes must be controllable.

Panellists were also asked to consider indicators that, from their own clinical experience, represented the greatest burden to population health for Indigenous Australians. Additional indicators considered to be relevant were added to the original list of 45 indicators to form a Master List. Three rounds of rating and consensus were then undertaken using this list as a starting point.

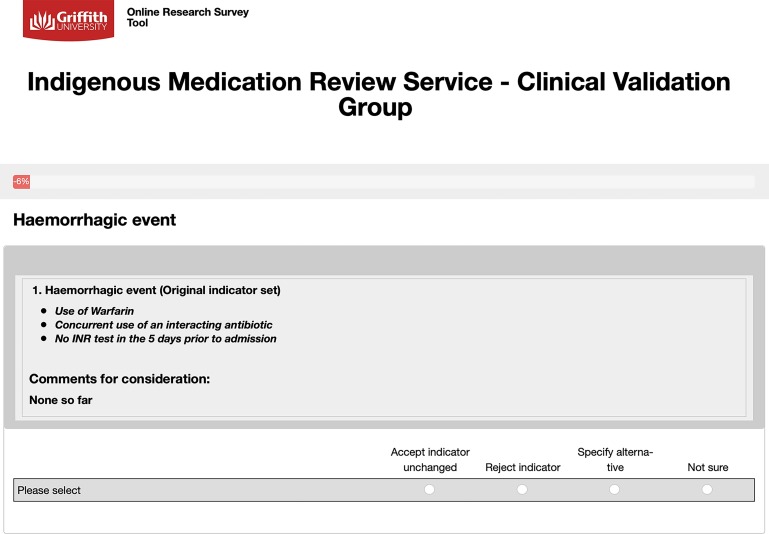

The first two rating rounds were sent to all panellists via email link in an online format hosted in LimeSurvey.28 Panellists were asked to carefully consider each indicator presented and then choose from four options: (i) accept indicator unchanged, (ii) reject indicator, (iii) specify alternative or (iv) not sure. Panellists were asked to provide comments or a rationale for rejecting an indicator or providing an alternative. An example of the online presentation of a clinical indicator to panellists is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

An example of the online presentation of a clinical indicator to panellists. INR, international normalised ratio.

The indicator was accepted unchanged if at least 70% of panellists chose the option ‘Accept indicator unchanged’ or rejected if at least 70% of panellists chose the option ‘Reject indicator’ in accordance with previous modified Delphi methods.29 The indicators which were accepted unchanged or rejected were removed and did not appear in subsequent rating rounds. All other indicators (where an alternative was proposed) were collated alongside the panellists’ comments or rationale, by the researchers. The researchers considered the comments, consulted any relevant clinical literature and offered alternative wording for the disputed indicator. Panellists’ comments were (anonymously) reported verbatim in the subsequent rating round, alongside the researchers proposed new wording of the indicator and links to any relevant clinical literature or guidelines. Researchers set a deadline of 2 weeks for responses after the online survey was opened. Panellists could login to the survey again if they had not completed it, and previous responses could be altered at any time prior to survey submission. Reminder emails were sent 1 week before the deadline and requests for additional time was granted for participants to complete the rating round, if required. Every effort was made by the research team to enable all 13 participants to complete the first two rating rounds.

The third rating round involved a face-to-face meeting of an invited subgroup (n=3) of the larger consensus group; a representative from each main speciality area (specialist doctor, general practice doctor, clinical pharmacist) provided expert commentary regarding any remaining discrepancies. Consensus in this final round was achieved following open group discussion which was moderated by the researchers (JS/AJW).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement has been achieved in the IMeRSe feasibility study, and will be ongoing over the study lifetime, through extensive collaboration with the relevant representatives of both Partner organisations. As described above (Selection of Delphi panellists), working with key Indigenous groups, both locally and as members of the Expert Panel, will be integral to the ongoing engagement process (eg, via the inclusion of community juries, councils and boards). This process will be informed by the local requirements at each site throughout this feasibility study. Acceptability outcomes for consumer participants will be assessed as described previously.15 Dissemination to Indigenous participants and communities will be a priority, with processes guided by the Expert Panel and informed by key stakeholders at a local site level.

Results

CVG panellists

A total of 13 panellists, five females and eight males, from five clinical areas participated between May 2018 and November 2018. Panellists had a mean of 17 years experience in their clinical areas and 11 years experience working with Indigenous people in their current role (table 1). Panellists were drawn from six of the nine states and territories across Australia and from urban, rural and remote locations (detailed information is withheld to maintain the anonymity of panellists).

Table 1.

Clinical validation group panel

| Clinical expertise | Number | % |

| Pharmacist | 5 | 39 |

| Specialist doctor | 3 | 23 |

| General practitioner | 2 | 15 |

| Researcher | 2 | 15 |

| Epidemiologist | 1 | 8 |

Clinical indicators

In addition to the original 45 indicators,11 panellists identified a further 56 new indicators. Hence, the Master List of indicators at the start of Round 1 rating comprised 101 indicators. During each of the rating rounds, panellists made suggestions to split and merge indicators, meaning the number of indicators for consideration could increase or decrease between rounds. The number of clinical indicators from the Master List accepted or rejected in each rating round, grouped by clinical presentation, are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Number of clinical indicators, grouped by clinical presentation and round

| Clinical presentation | Previous list* | Master list | Accepted round 1 | Accepted round 2 | Accepted round 3 | Rejected |

| Neurological | 7 | 17 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 0 |

| Vaccine preventable diseases | 0 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 0 |

| Electrolytes and laboratory abnormalities | 8 | 15 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 1† |

| Cardiovascular | 6 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 0 |

| Respiratory | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| Renal | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Fracture or falls | 4 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Haemorrhagic event | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Endocrine | 4 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Genitourinary | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 0 |

| Total† | 45 | 102 | 41 | 65 | 81 | 1 |

*The list of PPMRHs previously developed for the general Australian population.13 14

†NOTE: Totals are not cumulative as during the rating process, panellists suggested that some indicators should be merged or split.

PPMRHs, potentially preventable medication-related hospitalisations.

At the end of Round 2 rating, 65 indicators (80% of the final total) were agreed on by the panellists. The three-person subgroup of the CVG invited to undertake Round 3 rating formed consensus on the remaining 23 indicators during a 2 hour face-to-face meeting (one panellist phoned-in), moderated by the research team (JS/AJW). One clinical indicator was rejected during this round, with the remaining 22 indicators either accepted or merged with other indicators.

The final list of accepted indicators is presented in table 3. Thirty-four indicators from the original list of 45 were accepted by panellists, although 21 of these were updated in some way to reflect: (i) changes in current guidelines or new medicines, (ii) having been combined with other similar indicators for simplification, (iii) having been split into additional indicators for clarity. Forty-seven new indicators were added, giving a final total of 81 indicators.

Table 3.

Final list of potentially preventable medication-related hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians#

| Number | Hospitalisation outcome to avoid | Process of suboptimal clinical care prior to hospitalisation | Source |

| Haemorrhagic event | |||

| 1 | Haemorrhagic event | Use of warfarin; | Original |

| Concurrent use of an interacting antibiotic; | |||

| No INR test in the 5 days prior to admission. | |||

| 2 | Haemorrhagic event | Use of warfarin; | Original† |

| No INR test in the 6 weeks prior to admission. | |||

| 3 | Haemorrhagic event | Use of one or more antithrombotics (warfarin, DOAC, aspirin, NSAID, clopidogrel, LMWH); AND | Original† |

| No haemoglobin test within the past year; OR | |||

| No monitoring of renal function in the previous 6 months; OR | |||

| Use of triple therapy (dual antiplatelet plus oral anticoagulant) for more than 1 month prior to admission. | |||

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| 4 | Gastritis, GI bleed, GI ulcer or GI perforation | History of or prior hospitalisation for GI ulcers or GI bleed; | Original† |

| Use of NSAID (including aspirin) for a period of at least 1 month prior to admission. | |||

| 5 | Gastritis, GI bleed, GI ulcer or GI perforation | History of prior hospitalisation for GI ulcers or GI bleed; AND | Original† |

| Use of gastric toxin (eg, oral corticosteroids, NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, bisphosphonates, anticoagulants, cholinesterase inhibitor) for a period of at least 3 months prior to admission; AND | |||

| No cytoprotection (eg, proton pump inhibitor). | |||

| 6 | Bowel impaction | Use of two or more medications known to retard gastrointestinal motility (including anticholinergic agents, calcium channel blockers, antacids and iron preparations) at the time of admission; OR | Original† |

| Use of a highly anticholinergic agent at the time of admission; OR | |||

| Use of an opioid analgesic without concurrent use of a laxative at the time of admission. | |||

| Cardiovascular | |||

| 7 | Congestive heart failure or fluid overload | Prior hospitalisation for/or diagnosis of high blood pressure or CHF; | Original† |

| Use of an agent known to exacerbate CHF including NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, anti-arrhythmics (apart from beta-blockers or amiodarone), non-dihyropyridine calcium-channel blockers in systolic CHF (verapamil, diltiazem), corticosteroids, clozapine, tricyclic anti-depressants, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, thiazolidinediones or tumour necrosis factor antagonists at time of admission. | |||

| 8 | Congestive heart failure or fluid overload | Prior hospitalisation for/ or diagnosis of heart failure; | Original |

| No use of ACEI, ARB or ARNi (angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor) at time of admission. | |||

| 9 | Myocardial Infarction | History of acute coronary syndrome / previous MI; | Original† |

| No use of anti-platelet(s) OR beta-blocker (reduced left-ventricular systolic function only) OR HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor in the 3 months prior to hospitalisation. | |||

| 10 | Myocardial infarction | Insertion of stent within the previous 12 months; | New |

| No use of dual anti-platelet in 2 months prior to admission. | |||

| 11 | Thromboembolic cerebrovascular event | Prior diagnosis of atrial fibrillation; | Original† |

| No use of anticoagulant in the 3 months prior to admission in a patient with high risk according to CHA2Ds2Vasc score. | |||

| 12 | Acute coronary syndrome | CVD risk known to be >15% prior to admission; | New |

| Not on lipid lowering therapy AND/OR antihypertensive therapy. | |||

| 13 | Transient ischaemic attack/ischaemic stroke | Pulse quality/blood pressure not tested within past 24 months; | New |

| No use of any of antiplatelet, antihypertensive, anticoagulant, lipid lowering therapy. | |||

| 14 | Ischaemic coronary event | History of angina or acute coronary syndrome; | New |

| No use of beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker or nitrates. | |||

| 15 | Ischaemic event | History of diabetes; | New |

| History of ischaemic event; | |||

| No antiplatelet or lipid lowering therapy. | |||

| Electrolytes and laboratory abnormalities | |||

| 16 | Blood dyscrasia | Use of an agent known to cause blood dyscrasias (including carbimazole, sulphonylureas, propylthiouracil, methotrexate, sulphasalazine); | Original† |

| No complete blood count or platelet test in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| 17 | Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion | Use of TCAs, carbamazepine, ACEIs, other antidepressants; | Original† |

| No electrolyte test in the 12 months prior to admission. | |||

| 18 | Electrolyte imbalance | Use of diuretics, ACEI/ARB, spironolactone, potassium supplements or calcium supplements; | Original† |

| No electrolyte test in the 12 months prior to admission; AND | |||

| No renal function test in the 12 months prior to admission. | |||

| 19 | Anticonvulsant drug toxicity | Use of anticonvulsant requiring therapeutic drug monitoring; | Original |

| No drug level test in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| 20 | Digoxin toxicity | Use of digoxin; | Original† |

| No renal function test in the 12 months prior to admission; AND | |||

| No potassium serum level in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| 21 | Lithium toxicity | Use of lithium; | Original |

| No lithium drug level test in the 3 months prior to admission. | |||

| 22 | Clozapine-related blood dyscrasias | Use of clozapine; | New |

| No full blood count/white blood count/neutrophils/ eosinophils in >1 month prior to admission or within the previous week in the first 18 weeks of therapy. | |||

| 23 | Clozapine-induced myocarditis/cardiomyopathy | Use of clozapine; | New |

| No baseline echocardiogram; OR | |||

| ECG in the previous 12 months; OR | |||

| troponin in the previous 12 months; OR | |||

| CRP in previous 12 months before admission. | |||

| 24 | Clozapine toxicity/failure | Use of clozapine; | New |

| Altered smoking status while on clozapine (may vary levels and result in toxicity or relapse). | |||

| 25 | Clozapine toxicity | Use of clozapine; | New |

| Concurrent illness; | |||

| No full blood count/ white blood count/ neutrophils/ eosinophils in >1 month prior to admission. | |||

| Endocrine | |||

| 26 | Hypoglycaemia | Use of insulin; OR | Original† |

| Use of long-acting sulfonylurea in the 3 months prior to admission; AND | |||

| Inadequate blood glucose monitoring OR reduced adherence to diabetes treatment plan. | |||

| 27 | Diabetic complications (including hyperglycaemia) | Previously diagnosed with diabetes; | Original† |

| Use of a hypoglycaemic in the 6 months prior to admission; AND | |||

| No HbA1c in previous 6 months. | |||

| 28 | Hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis | Use of amiodarone or lithium; | Original† |

| No thyroid function test in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| Fracture or falls | |||

| 29 | Hip fracture or other fracture/break | Aged 65 years or older; AND | Original† |

| Use of long-term corticosteroids (>1 month); AND/OR | |||

| Use of sedating psychotropic medication (including TCAs, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, opioids); AND/OR | |||

| Use of cardiovascular drugs with high potential to cause postural hypotension (including nitrates, centrally acting adrenergic blockers and alpha-receptor blockers). | |||

| 30 | Hip fracture | Female gender; | Original |

| Prior fall from the standing level resulting in fracture; | |||

| No use of HRT, bisphosphonate or other osteoporosis medicine in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| 31 | Hip fracture | Male gender; | Original |

| Prior fall from the standing level resulting in fracture; | |||

| No use of bisphosphonate or other osteoporosis medicine in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| 32 | Low-trauma fracture | Previous low-trauma fracture; | New |

| Not taking osteoporosis prevention therapy at time of admission. | |||

| Neurological | |||

| 33 | Acute confusion | Urinary tract infection un/inadequately treated | New |

| 34 | Acute confusion | Use of two or more anticholinergic agents at the time of admission; OR | Original† |

| Use of a highly anticholinergic agent at the time of admission; OR | |||

| Use of two or more of sedating prescription drugs and/or sedating antihistamines; OR | |||

| Use of multiple psychotropic medicines (≥3 unique medicines from ATC groups, N05 or N06) at the time of admission. | |||

| 35 | Seizure | Use of an anticonvulsant; | Original† |

| Concurrent use of a medication which lowers the seizure threshold (as specified in the Australian Medicines Handbook); AND/OR | |||

| Reduced compliance with anticonvulsant medication. | |||

| 36 | Bipolar disorder | Prior hospitalisation for bipolar disorder; | Original |

| Use of lithium; | |||

| No lithium drug level in the 3 months prior to admission. | |||

| 37 | Bipolar affective disorder/psychotic disorder | Prior hospitalisation for bipolar disorder; | New |

| No use of/ poor compliance with a mood stabiliser; OR | |||

| Reduced compliance with long acting injection and/or oral medication. | |||

| 38 | Depression | Prior diagnosis of depression; | Original |

| Concurrent use of a moderately highly lipophilic beta blocker. | |||

| 39 | Depression (readmission) | Reduced compliance with antidepressant or augmenting medications (mood stabiliser or antipsychotic); AND/OR | New |

| No review (including medication adherence) undertaken post previous admission. | |||

| 40 | Mania/hypomania | Use of antidepressants in the 2 months prior to admission; | New |

| No use of mood stabiliser in the 2 months prior to admission. | |||

| 41 | Attempted suicide | Use of SSRI in adolescents (up to 20 years old); | New |

| No psychiatric review in 12 months prior to admission. | |||

| 42 | Psychotic episode | History of psychosis/ mental illness; | New |

| Reduced compliance with prescribed antipsychotic/ anxiolytic medication. | |||

| 43 | Antidepressant withdrawal symptoms | Abrupt cessation of antidepressant (especially short-acting such as paroxetine and venlafaxine). | New |

| 44 | Acute anxiety | Cessation of psychotropic medications (such as antidepressant and/or benzodiazepines) without monitoring. | New |

| 45 | Eating disorder/electrolyte imbalance | Excessive laxative use; OR | New |

| Use/abuse of medications altering electrolyte levels (for example, loop diuretics). | |||

| 46 | Serotonin toxicity | Use of multiple serotonergic agents that may contribute to serotonin toxicity (desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, MAOIs including moclobemide, SSRIs, TCAs, venlafaxine, fentanyl, tramadol, selegiline, lithium, tryptophan, St. John’s Wort). | New |

| Renal | |||

| 47 | Renal failure | Use of ACEI or ARB; | Original† |

| No BUN or serum creatinine test in the 12 months prior to admission. | |||

| 48 | Renal failure | Use of allopurinol; | Original |

| No BUN or serum creatinine test in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| 49 | Renal failure | Use of lithium; | Original |

| No BUN or serum creatinine test in the 3 months prior to admission. | |||

| 50 | Renal failure | NSAID use for>3 months; | New |

| BUN or serum creatinine not monitored in the previous 12 months. | |||

| 51 | Renal failure | Use of methotrexate; | New |

| No BUN or serum creatinine test in the 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| Respiratory | |||

| 52 | Asthma AND/OR COPD | Prior hospitalisation for/or diagnosis of asthma/COPD; AND | Original† |

| No / inadequate maintenance therapy (LAMA, LABA, ICS); OR | |||

| Poor inhaler technique; AND/OR | |||

| No action plan in place; AND/OR | |||

| No smoking cessation advice given. | |||

| 53 | Asthma/COPD | Prior hospitalisation for/or diagnosis of asthma and/or COPD; | Original |

| Use of beta-blocker eye drops for glaucoma at the time of admission. | |||

| 54 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Prior hospitalisation for/or diagnosis of COPD; | Original |

| Use of a betablocker at the time of admission. | |||

| 55 | Acute respiratory failure | Prior hospitalisation for/or diagnosis of COPD; | Original |

| Use of a medium to long-acting benzodiazepine at the time of admission. | |||

| 56 | Asthma | Prior hospitalisation for/or diagnosis of asthma/COPD; | New |

| High use (>2X per week) of a short-acting bronchodilator (SABA, SAMA); | |||

| No use of maintenance therapy (LAMA, LABA, ICS). | |||

| 57 | Bronchiectasis | Two or more admissions with bronchiectasis exacerbations in last 12 months; No prophylactic azithromycin trialled in the 12 months prior to admission. |

New |

| Genitourinary | |||

| 58 | Urinary retention | Prior diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia OR bladder atony due to diabetes mellitus; | Original† |

| Current use of a drug with anticholinergic effects or an opioid at the time of admission. | |||

| 59 | Recurrent urinary tract infection | No test for organism identification and sensitivity undertaken. | New |

| Sexually transmitted diseases | |||

| 60 | Chlamydia or gonorrhoea | Untreated with antibiotics for more than 1 week after results received. | New |

| Vaccine preventable diseases | |||

| 61 | Pneumonia | No pneumococcal vaccine if 'at risk' (chronic illness or>50 years); | New |

| No revaccination after 5 years. | |||

| 62 | Influenza | No influenza vaccination in the past 12 months. | New |

| 63 | Tetanus | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 64 | Diphtheria | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 65 | Whooping cough | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 66 | Acute poliomyelitis | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 67 | Varicella | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 68 | Measles | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 69 | Rubella | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 70 | Mumps | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 71 | Hepatitis A | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| 72 | Hepatitis B | No/incomplete vaccination. | New |

| Other | |||

| 73 | Cellulitis | No treatment / inadequate treatment with antibiotics to treat staphylococcus aureus or streptococcus pyogenes with an appropriate antibiotic at time of admission. | New |

| 74 | Rheumatic fever (<21 years of age) | Prior diagnosis of rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease; | New |

| No benzathine penicillin (or erythromycin if allergic) in the last 28 days. | |||

| 75 | Gout attack | Previous history of gout; | New |

| Use of loop diuretics or thiazide diuretics. | |||

| 76 | Hepatitis C | No treatment with direct acting antivirals. | New |

| 77 | Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infection | Recurrent skin infection (>2 weeks); | New |

| Continuing use of β-lactam antibiotic; | |||

| No skin swab taken. | |||

| 78 | Jaw osteonecrosis | Use of a bisphosphonate or denosumab; | New |

| No dental assessment within 6 months prior to admission. | |||

| 79 | Trachoma | Untreated with appropriate antibiotics. | New |

| 80 | Iron deficiency anaemia | Confirmed pregnancy; | New |

| No FBE test during pregnancy. | |||

| 81 | Eclampsia | Prior diagnosis of hypertension (a systolic blood pressure of greater than or equal to 160 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 110 mm Hg) during the current pregnancy; |

New |

| No treatment with antihypertensive agent (suitable for use in pregnancy) at time of admission. | |||

*The final list of clinical indicators has not been considered as part of any independent Health Technology Assessment (HTA) for effectiveness/cost-effectiveness.

†The original indicator (from Kalisch et al14) forms the basis of this indicator but it has been modified either to (i) update the indicator to reflect current guidelines or new medicines in the class; (ii) combine with another indictor/s for simplification or (iii) has been split into more indicators for clarity.

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II blockers; ARNi, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors; ATC, anatomical therapeutic chemical; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CHA2Ds2Vasc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes and stroke/TIA vascular disease (peripheral arterial disease, previous MI, aortic atheroma) (female gender is also included in this scoring system); CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease;DOAC, Direct oral anticoagulant; FBE, full blood examination; GI, gastrointestinal; HbA1c, glycolated haemoglobin; Hg, mercury; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids;INR, international normalised ratio; LABA, long-acting beta agonists; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; MI, myocardial infarction; MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SABA, short-acting beta-2 agonists; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Discussion

The development of this updated clinical indicator list is an important step in addressing MRPs for Indigenous Australians. This study builds on earlier work which identified a set of clinical indicators for use in a general Australian population.13 14 The new list includes 81 indicators, sourced from 34 of the original 45 indicators and 47 newly identified indicators. In comparison to the general Australian population list, the new list contains more neurological indicators (expanded from 7 to 14), vaccine preventable diseases (expanded from 0 to 12) and ‘other’ indicators (expanded from 0 to 9), which better reflects the health burden of the Indigenous population. For example, trachoma and rheumatic heart disease are health issues seen in the Indigenous population, but rarely in the general Australian population.

Panellists included specialist and general practice doctors, pharmacists, epidemiologists and researchers, the majority of whom had extensive experience in providing healthcare for Indigenous populations. The purpose of conducting this research was two-fold: first to provide a prespecified list of PPMRHs to define the primary outcome measure for the IMeRSe feasibility study15; and as a resource for pharmacists conducting medication reviews for Indigenous Australians to assist in identifying suboptimal processes of primary care related to medication use, defined for the IMeRSe feasibility study as serious MRPs.15

AHSs offer Indigenous Australians access to holistic and person-centred primary care. The inclusion of pharmacists undertaking medication review services is important as much of the health burden experienced by Indigenous Australians results from chronic conditions such as renal and/or cardiovascular disease, type-II diabetes and mental illness, which in turn increases the requirement for ongoing medication regimens.1 30 There are reports that the levels of MRPs among Indigenous populations are of concern,31 32 although there is scant evidence of the size or extent of the problem. Further, Indigenous populations access the existing government funded medication review services, The MedsCheck and Diabetes MedsCheck Programme provides for in-pharmacy reviews of consumers who are taking multiple medications and/or have newly diagnosed or poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. These reviews are aimed at enhancing the quality use of medicines and reducing the number of adverse drug events experienced by consumers. A Home Medicines Review is designed to enhance the quality use of medicines and reduce the number of adverse medicine events by assisting consumers to better manage and understand their medicines through a medication review conducted by an accredited pharmacist in the patient's home (http://www.6cpa.com.au/medication-management-programs) at a lower rate than non-Indigenous Australian for reasons including the lack of culturally responsive services, not having established and trusting relationships with pharmacists and because pharmacists are not usually integrated into AHSs.16 17

The clinical indicator list developed in this study will be tested for predictive validity in two ways through the IMeRSe feasibility study: (i) as a primary outcome measure and as such, will be used to classify a set of serious MRPs which can be analysed against a list of all MRPs (regardless of severity); and (ii) to estimate the rate of PPMRHs in Indigenous populations using a linked administrative data set comprised of 5 years of hospital admissions from the state of Queensland, Australia. This data set will be combined with pharmaceutical and medical services usage for the same cohort of hospitalised individuals (collected by the national government). Thus, the background rate of PPMRHs can be identified, for arguably the most representative state in Australia in terms of Indigenous Australians, as urban, rural and remote populations are all included. However, it is anticipated that it will not be possible to measure some of the indicators using these existing administrative databases as insufficient clinical information (such as cardiovascular disease risk) will be available. It is possible that this problem may decline over time as individual health records become fully digitalised and shared in Australia.

The processes contributing to suboptimal clinical care specified in the final indicator list (table 3) are termed serious MRPs; these may, or may not, result in a hospitalisation. Only when a hospitalisation does occur is a PPMRH realised. Thus, we are interested not only in the rate of PPMRHs in the Indigenous population, but also the rate of MRPs and the translation rate of MRPs to PPMRHs. The reduction in MRPs of all severity, including serious MRPs, is a key outcome of IMeRSe feasibility study.

A modified Delphi technique was used in this study to reach consensus between experts. The Delphi technique allows for anonymity in responses, which permits all panellists an equal chance to have their opinion considered. A majority consensus was reached for 65 (80%) of the total number of indicators at the end of Round 2 rating. Of the remaining indicators (n=23), the majority required only a short discussion and/or brief changes to wording to reach consensus Round 3 rating. The researchers considered that this meeting expediated consensus on the remaining indicators and was a strength of the study. It must be noted that use of the term ‘consensus’ here, especially in the early phases of the Delphi process, is in fact ‘convergence’ of expert opinion. However, consensus has been assumed because : (i) panellists were made aware that they were involved in a decision-making process at the start, (ii) justification for non-acceptance was fed-back to the group between rounds and (iii) face-to-face discussions were held to reach agreement in Round 3.

Unlike the RAND appropriateness method, the modified Delphi rating process did not incorporate a formal mechanism for considering the strength of evidence of the proposed indicators. This aspect could not be incorporated into the present study, due to the lack of relevant research specifically involving Indigenous Australians, and hence the lack of evidence for this specific patient population. However, the existing indicator list, which was adapted for the present study was developed using the RAND appropriateness measure,13 and considered the strength of evidence underpinning each indicator during the indicator development process. Thirty-four of the indicators accepted in the present study were based on existing indicators, so nearly half of the indicators were developed by explicitly considering the strength of evidence for the particular indicator. During the moderated online and face-to-face discussions, the researchers observed that clinicians incorporated current clinical guidelines into their decision-making processes, although this was not undertaken in a formal way. This could be viewed as a potential limitation of the study. Another possible limitation was the relatively small number of panellists who agreed to participate, which could be due to workload pressures for clinicians working in Indigenous health in Australia. Finally, the authors note that the final list of clinical indicators developed here are not necessarily independent of each other, nor are they of equal weighting of clinical seriousness. Thus, this issue will need to be accounted for in the data analysis of the PPMRHs for the IMeRSe study.

By classifying a list of serious MRPs, the importance of other MRPs may be discounted. The lack of adherence to medication regimens among Indigenous populations is of particular concern, especially given the high rates of chronic disease such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, severe mental illness and renal disease that require regular medication. Barriers that limit adherence including poor health literacy, lack of access to medications (cost and physical access) and medication sharing with relatives and friends can all negatively impact on health through uncontrolled illness.31 In the short-term, health decrements due to low medication adherence may not result in hospitalisation, it may nonetheless contribute to life-threatening outcomes in the medium-to-longer term. It must be stressed that the final clinical indicator list developed here should only be used by pharmacists and other health professionals undertaking medication review services as a resource to optimise medication management. It does not provide a definitive list of the most serious problems, nor does it replace clinical judgement.

Conclusions

The final list of clinical indicators developed in this study represents an initial, but important, step in quantifying serious MRPs and PPMRHs in Indigenous Australian populations. Such a list is not static and should be regularly updated in light of changes to clinical guidelines and medicines formularies. The health of Indigenous Australians may be enhanced by using this list as a resource during the process of medication review to identify suboptimal processes of care and then institute corrective processes to prevent a potential hospitalisation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Indigenous Medication Review Service (IMeRSe) feasibility study has been developed in partnership with The Pharmacy Guild of Australia, the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and Griffith University. The authors would like to acknowledge the time and experience of the panellists who participated in this study and Dr Helen Stapleton for providing feedback on the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank the Expert Panel for their ongoing contribution to the IMeRSe study. This activity received grant funding from the Australian Government. The researchers were independent from the funder. This article contains the opinions of the authors and does not in any way reflect the views of the Department of Health or the Australian Government. The financial assistance provided must not be taken as endorsement of the contents of this article. There was no direct public or patient involvement in the research reported in this manuscript, however, patient and public involvement has been achieved in the IMeRSe feasibility study.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. The article title and Abstract have been updated.

Contributors: JS was responsible for study concept, design, data collection and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AJW designed the research protocol, is the principle investigator and was involved in the design and data collection. LK, GS, TT and DW contributed to methodology and data collection. All authors were involved in the revision of this paper and made a contribution to the intellectual content and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: This activity received grant funding from the Australian Government.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted from Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (GU ref No:2018/126) for this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The data set generated and analysed for this study is not publicly available as consent from participants was not sought to share the data more widely than for the purpose of this study.

Please note that the use of the term ‘Indigenous’ in this manuscript includes all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and acknowledges their rich traditions and heterogenous cultures.

References

- 1. Australian Government Department of Health National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2013-2023 2013.

- 2. Freeman T, Edwards T, Baum F, et al. Cultural respect strategies in Australian Aboriginal primary health care services: beyond education and training of practitioners. Aust N Z J Public Health 2014;38:355–61. 10.1111/1753-6405.12231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griese-Mammen N, Hersberger KE, Messerli M, et al. PCNE definition of medication review: reaching agreement. Int J Clin Pharm 2018;40:1199–208. 10.1007/s11096-018-0696-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jokanovic N, Tan ECK, van den Bosch D, et al. Clinical medication review in Australia: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2016;12:384–418. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Mil JWF, Westerlund LOT, Hersberger KE, et al. Drug-Related problem classification systems. Ann Pharmacother 2004;38:859–67. 10.1345/aph.1D182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eichenberger PM, Lampert ML, Kahmann IV, et al. Classification of drug-related problems with new prescriptions using a modified PCNE classification system. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:362–72. 10.1007/s11096-010-9377-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peterson G, Identifying TP. Prioritising and documenting drug-related problems. Aust Pharm 2004;23:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roughead EE, Gilbert AL, Sansom LN, et al. Drug‐related hospital admissions: a review of Australian studies published 1988‐1996. Medical Journal of Australia 1998;168:405–8. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb138996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robertson HA, MacKinnon NJ. Development of a list of consensus-approved clinical indicators of preventable drug-related morbidity in older adults. Clin Ther 2002;24:1595–613. 10.1016/S0149-2918(02)80063-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sauer B, Hepler C, Cherney B, et al. Computerised indicators of potential drug-related emergency department and hospital admissions. Am J Manag Care 2007;13:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. MacKinnon N, Hepler C. Preventable drug-related nmortality in older adults. 1. indicator development. J Manag Care Pharm 2002;8:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morris CJ, Cantrill JA, Hepler CD, et al. Preventing drug-related morbidity--determining valid indicators. Int J Qual Health Care 2002;14:183–98. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.intqhc.a002610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caughey GE, Kalisch Ellett LM, Wong TY. Development of evidence-based Australian medication-related indicators of potentially preventable hospitalisations: a modified Rand appropriateness method. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004625 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalisch LM, Caughey GE, Barratt JD, et al. Prevalence of preventable medication-related hospitalizations in Australia: an opportunity to reduce harm. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:239–49. 10.1093/intqhc/mzs015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wheeler AJ, Spinks J, Kelly F, et al. Protocol for a feasibility study of an Indigenous medication review service (IMeRSe) in Australia. BMJ Open 2018;8:e026462 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Swain L, Barclay L. Medication reviews are useful, but the model needs to be changed: perspectives of Aboriginal health service health professionals on home medicines reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:366 10.1186/s12913-015-1029-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swain L, Barclay L. Exploration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives on home medicines review. Rural Remote Health 2015;15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campbell SM, Ja B, Hutchinson A. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:358–64. 10.1136/qhc.11.4.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical Guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998;2:1–88. 10.3310/hta2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hutchinson A, Fowler P. Outcome measures for primary health care: what are the research priorities? Br J Gen Pract 1992;42:227–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011;6:e20476 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group techniques for program planning: a guide to nominal group and Delphi processes: Scott, Foresman Glenview. IL 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, et al. A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1986;2:53–63. 10.1017/S0266462300002774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shekelle P, Kahan J, Park R, et al. Assessing appropriateness by expert panels: how reliable? J Gen Intern Med 1995;10. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shekelle PG, Kahan JP, Bernstein SJ, et al. The reproducibility of a method to identify the overuse and underuse of medical procedures. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1888–95. 10.1056/NEJM199806253382607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990;47:533–43. 10.1093/ajhp/47.3.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Limesurvey G. Limesurvey: an open source survey tool. Limesurvey GmbH H, Germany, editor: In. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tolsgaard MG, Todsen T, Sorensen JL, et al. International Multispecialty consensus on how to evaluate ultrasound competence: a Delphi consensus survey. PLoS One 2013;8:e57687 10.1371/journal.pone.0057687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Australian Government Depertment of Health Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a mental health condition. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hamrosi K, Taylor S, Aslani P. Issues with prescribed medications in Aboriginal communities: Aboriginal health workers’ perspectives. Rural Remote Health 2006;6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davidson PM, Abbott P, Davison J, et al. Improving medication uptake in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2010;19:372–7. 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.