Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to explore firefighters’ and police officers’ experiences of responding to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in a dual dispatch programme.

Design

A qualitative interview study with semi-structured, open-ended questions where critical incident technique (CIT) was used to collect recalled cardiac arrest situations from the participants’ narratives. The interviews where transcribed verbatim and analysed with inductive content analysis.

Setting

The County of Stockholm, Sweden.

Participants

Police officers (n=10) and firefighters (n=12) participating in a dual dispatch programme with emergency medical services in case of suspected OHCA of cardiac or non-cardiac origin.

Results

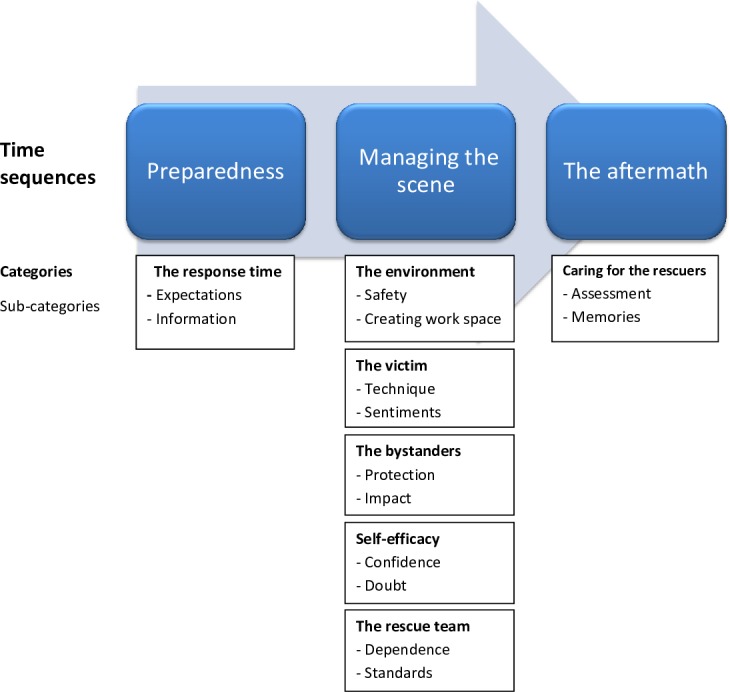

Analysis of 60 critical incidents was performed resulting in three consecutive time sequences (preparedness, managing the scene and the aftermath) with related categories, where first responders described the complexity of the cardiac arrest situation. Detailed information about the case and the location was crucial for the preparedness, and information deficits created stress, frustration and incorrect perceptions about the victim. The technical challenges of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation and managing the airway was prominent and the need of regular team training and education in first aid was highlighted.

Conclusions

Participating in dual dispatch in case of suspected OHCA was described as a complex technical and emotional process by first responders. Providing case discussions and opportunities to give, and receive feedback about the case is a main task for the leadership in the organisations to diminish stress among personnel and to improve future OHCA missions.

Keywords: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, critical incident technique, firefighters, first responders, out–of–hospital cardiac arrest, police officers

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Few other studies concerning first responders’ experiences about participating in dual dispatch with emergency medical services in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest have previously been published.

The study provides new insights from first responders about the complex situation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

One limitation of the study is the risk of recall bias.

Qualitative studies propose a deeper understanding of a phenomenon, but the results cannot be generalised to any other group of first responders or organisations.

New theories and fields of research can be developed from the results.

Introduction

To improve outcome in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) several prehospital measures have been introduced worldwide, for example, different types of public access defibrillation programmes1 and implementation of dual dispatch systems including emergency medical services (EMS), firefighters and/or police officers, that is, first responders (FRs), trained in basic life support (BLS) dispatched in case of suspected OHCA.2–5 In the County of Stockholm, Sweden, a dual dispatch system involving EMS and firefighters was introduced in 2005.6 Police officers were fully integrated in the OHCA alarm system in 2012.7 Experiences of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outside hospital are mostly explored within the bystander population.8–12 Previous research in regard to FRs experiences of participating in emergency call-outs has been described in the context of traffic accidents13 and psychological consequences about performing CPR and using an automated external defibrillator (AED).14

The aim of this interview study was to explore firefighters’ and police officers’ experiences of saving lives in OHCA in a dual dispatch programme.

Methods

Design

This was an interview study where data were analysed by using critical incident technique (CIT)15 and inductive qualitative content analysis.16 A ‘critical incident’ (CI) in this study is a description of a cardiac arrest situation recalled as important by the participants. OHCAs were included independent of aetiology (medical or non-medical) and age of the victim.

Study setting and dispatch

The study was conducted in Stockholm County covering 6519 km2 with 2.3 million inhabitants living in densely populated urban areas, as well as in more rural parts. In case of a suspected OHCA, the dispatchers at the Emergency Medical Communication Centre (EMCC) first dispatches two ambulances staffed with specialist nurses and emergency medical technicians performing advanced life support.17 In special circumstances such as major trauma, drowning and paediatric cardiac arrests, a physician-staffed rapid response vehicle is alerted. FRs trained in BLS, and equipped with AEDs are also dispatched, primarily the firefighters and thereafter the police.18 The EMS, police force and fire department are alerted by the common emergency number (112). In Stockholm County, there are 40 fire stations and 30 police stations. Depending on time of day and type of vehicles being dispatched, the number of attending staff varies between 4 and 10 in average. The police are considered to be an extra resource in OHCA, and cannot always engage depending on other ongoing missions. Approximately 1200 confirmed OHCA occurs annually, and FRs are being dispatched in estimated 70% of these cases.

CPR training among FRs

Annual adult and paediatric BLS training is recommended for FRs by European guidelines in CPR18 and the Swedish Resuscitation Council. However, compliance to these recommendations could differ between participating organisations. It is mandatory for FRs to start CPR if first on scene unless obvious signs of death are present.

Participants

Eligible participants were firefighters and police officers with experiences of being dispatched as FRs in OHCA. The recommended sample size in CIT depends on what activity or behaviour being studied. If the activity is relatively well-defined, a total number of 50 to 100 critical incidents (CIs) are needed for the analysis.15 19 With an estimate of 2–4 CIs per interview, a sample size of approximately 20 interviews was considered sufficient.

Data collection

The strategy used was a purposive sampling of key participants with knowledge from one or more cardiac arrest situations, with the main focus to collect as rich descriptions as possible.20 To obtain a variety of workplaces, different ages and gender, three approaches for recruitment were used: 1) an invitation letter from the researchers was presented to the main collaboration group for OHCA alarms in Stockholm County; 2) on the police report for cardiac arrest alarms there was a request to contact the researchers for a voluntary interview; 3) fire stations were directly contacted for recruitment of participants. All three approaches were used, and all voluntary participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included.

The final study sample consisted of 22 participants; 12 firefighters representing four different fire brigades, and 10 police officers from eight police stations throughout the County. The participants received written information about the study and contact information to the researchers before the interviews took place. An interview guide with open-ended semi-structured questions was used (box 1).

Box 1. Interview guide for collecting critical incidents.

Can you describe a particular situation and the circumstances surrounding it when you have been dispatched to a person suffering from an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Please describe the circumstances and the time.

Can you describe how you acted in this situation?

Can you describe how other persons acted in this situation?

Can you describe how you reacted?

What was the result of the situation?

Do you want to add something more?

Data of demographic character were also collected. The participants could choose the place for the interview, and all except three took place at their regular workplaces. The interviews lasted between 9 and 38 min (22 min in median), and were all conducted by the first author (IH-A), a nurse anaesthetist and teacher with professional knowledge in OHCA research, especially CPR/defibrillation and dual dispatch. The interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder (Olympus VN-7800PC), and transcribed verbatim by a secretary with knowledge of cardiac arrest research. A pilot interview to test the questions in the interview guide was performed in February 2015. No change of questions was needed. The pilot interview contained rich material with descriptions from three CIs, and were therefore included in the final analysis. The following interviews were carried out from 16 June to 13 December 2016.

Data analysis

The analysis was performed as follows: (1) identification of CIs as the unit of analysis in each interview. The CIs were thereafter read repeatedly to gain a comprehensive view of the whole; (2) condensation of each CI into meaning units with the purpose to reduce the text and preserve the core in the narrative. A meaning unit is close to the text and is not interpreted by the researchers at this stage; (3) interpretation and coding the meaning units into subcategories by the authors and (4) the subcategories were thereafter merged into categories from which time sequences were created (table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the analysis process

| Critical incident (CI) | Condensed meaning units | Sub category |

Category | Time sequence |

| There was some sort of crack house; a younger girl had a cardiac arrest. And then you think before going in, there is a second type of threat scenario when entering… | Crack house Younger girl Cardiac arrest Think before going in Second threat |

Safety | The environment | Managing the scene |

Excerpt from CI #1 (firefighter #1).

To ensure rigour and consistency of interpretation, the analysis was discussed by the researchers, and agreement was reached at every step after dialogue between the co-researchers, to ensure that all analyses were supported by the data. In the analysis, the participants were anonymised for the researchers.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants and information was given about the possibility to withdraw from the study without any reprisal. Participants were not entitled to financial remuneration or other benefits.

Patient and public involvement

The patients and the public were not involved in planning or the design of this study.

Results

Baseline characteristics are presented in table 2. Median age was 36 years and the working experience as firefighter and police officer were 6.5 years in median for both professions. Firefighters were predominantly men, and they had longer experience of being dispatched to an OHCA than the participating police officers.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants (n=22)

| F/P 55/45 % |

Age (y) Mean=36 |

Sex M/F 77/23 % |

Prof exp. (y) Mean=7.5 |

No. of CA |

Years in OHCA dispatch | Latest CPR course (y) Mean=1 |

CPR level | CC yes/no 100/0 % |

Vent. yes/no 73/27 % |

Defibr.* yes/no 77/23 % |

Healthcare edu.† yes/no 45/55 % |

| F1 | 23 | M | 3.5 | 11–20 | 0–3 | 1 | PLS/ILS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F2 | 47 | M | 9.5 | >20 | 8–10 | 1 | PLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F3 | 26 | M | 3.5 | 11–20 | 0–3 | 1 | PLS/ILS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| F4 | 43 | M | 5 | >20 | 4–7 | 1 | PLS/ILS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F5 | 50 | M | 27 | >20 | 8–10 | 1 | BLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| F6 | 54 | M | 11 | >20 | 8–10 | 1 | BLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F7 | 43 | M | 10 | >20 | 8–10 | 1 | BLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| F8 | 28 | M | 7 | 0–5 | 0–3 | 1 | ILS | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| F9 | 35 | M | 2 | 11–20 | 0–3 | 1 | ILS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| F10 | 36 | M | 11 | >20 | 8–10 | 1 | PLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| F11 | 27 | F | 6 | >20 | 4–7 | 1 | ILS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| F12 | 28 | M | 5 | 6–10 | 4–7 | 1 | ILS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| P1 | 40 | M | 7 | >20 | 4–7 | >2 | ILS | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| P2 | 31 | F | 3 | 0–5 | 0–3 | 1 | ILS | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| P3 | 30 | M | 2 | 6–10 | 0–3 | 1 | BLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| P4 | 43 | M | 13 | >20 | 4–7 | 1–2 | ILS | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| P5 | 26 | M | 2 | 0–5 | 0–3 | 1–2 | BLS | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| P6 | 38 | F | 10 | 6–10 | 8–10 | 1 | ILS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| P7 | 28 | F | 2.5 | 11–20 | 0–3 | 1–2 | ILS | Yes | No | No | No |

| P8 | 33 | M | 6 | 0–5 | 4–7 | 1 | BLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| P9 | 40 | M | 9 | 0–5 | 0–3 | 1 | BLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| P10 | 41 | F | 9 | 6–10 | 0–3 | >2 | ILS | Yes | No | No | Yes |

*Automated external defibrillator applied and electric chock administered.

†Healthcare education besides regular professional training as firefighter/police officer.

CA, cardiac arrest; CC, chest compressions; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; Defibr., defibrillation; F/P, firefighter/police officer; M/F, male/female; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PLS/ILS/BLS, pediatric life support/immediate life support/basic life support; y, years.

The total number of CIs were 60, varying from one to five per participant. Police officers described in median three CIs, compared with two for the firefighters. During the analysis, 7 categories and 14 subcategories emerged which reflects three major time sequences describing the temporal continuity of the OHCA situation: (1) preparedness, (2) managing the scene, (3) the aftermath (figure 1). They are presented with suitable citations to highlight important aspects of each time sequence. The firefighters are referred to as ‘F’ and the police officers as ‘P’.

Figure 1.

Time sequences, categories and subcategories.

Preparedness

This time sequence comprises the response time, which is defined as from incoming emergency call received at the EMCC, to arrival of FRs at the scene.

The response time

Expectations were grounded in the participants’ previous experiences and mental pictures of what was expected to happen. If the victim’s characteristic was not communicated by the EMCC, both firefighters and police officers described that they had a preconceived perception of the victim as an older person. Valuable time for both technical and mental preparations could then be delayed if the victim proved to be a child or a young adult.

Information deficit about the case was described as a considerable problem and caused stress and frustration among FRs, especially when not finding the address, entry code to the building or when there was no bystander present showing the way. “We were trying to find the address; we were on the right street but we couldn’t find the right number….//…We started to feel frustration building up: Damn! We can’t find it”. (F10)

Managing the scene

The time sequence was defined as from when the FRs vehicle stops at the address, to departing from the location.

The environment

To be able to start CPR the FRs had to take control over the environment. Threats from bystanders and traffic caused anxiety, especially if there were few FRs in place from the beginning and they had to focus mainly on the victim, instead of prioritising their own safety first.

So there we were in the middle of the motorway doing compressions, we were like, just right there, in the middle of the road, doing compressions. (F10)

Obstacles had to be taken care of, that is, extraction from vehicles, removing furniture or placing the victim in supine position to be able to start resuscitation.

The victim

The victim could be described in both a technical and emotional way as heavy, still warm or disgusting to take care of when regurgitation had occurred. Performing manual chest compressions was recounted by FRs as a repulsive task depending on flail chest caused by the resuscitation.

What I often think about is that when you do compressions, ribs get broken and I think that is so horrible. That’s really the thing that affects me the most, whenever I do compressions or when I think about cardiac arrest alarms. (F6)

When futile to resuscitate the victim, FRs often described the situation as sad or disappointing, especially when young people died in accidents or drug abuse. The mental strain could be considerable if the FRs children were at similar age as the deceased.

It was a young girl. It just feels so damned awful and you know when you’ve got two girls of your own as well, it just feels awful….//…they had taken cocaine, amphetamine…// (F5)

Managing the airway was specified to be the most difficult technical skill, especially among the police officers. This is also shown in table 2 where six (60%) of the police officers used compressions-only technique when resuscitating.

The bystanders

Comforting and taking care of bystanders was an extensive part of the assignment and many of the FRs expressed how laborious this task could be. Lack of education in handling emotional crisis after a cardiac arrest was emphasised. There were also no clear instructions where the FRs responsibility ended when the EMS had left. To leave an elderly person alone afterwards when the spouse had passed away was expressed as difficult.

I think we stayed there for almost an hour after the ambulance had left…//…She had some problems walking, this old lady. So we put lots of bottles of juice and stuff by the armchair where she used to sit so she wouldn’t have to walk about and fetch things, because that was what her husband had done for her, before he had his cardiac arrest. (F12)

Although protective towards the bystanders, FRs could also be critical, especially personnel in elderly care facilities were described as passive and not knowing how to act in OHCA situations.

Self-efficacy

The FRs were moving between confidence and doubt when talking about their own capacity in the OHCA situation. A circumstance mentioned was when the case was not a cardiac arrest but some other illness. To make medical decisions before arrival of EMS without appropriate training in first aid was described as extremely difficult and stressful, especially for the police officers.

I don’t have any medical training; I could see that half of the brain was out, maybe it works anyway, I don’t have enough knowledge to decide. (P5)

The FRs could describe fear of doing more harm than good, but also satisfaction with their own work, knowing that they had played a significant role for the outcome.

The rescue team

Pronounced feelings of togetherness and dependence were noticeable, and the FRs trusted each other’s ability to manage critical situations. Protocols for handling OHCA situations, especially among the firefighters, were expressed as ‘our guiding star’ (F9), and they could also describe a clear structure for teamwork. This was not marked among the police officers who could feel loneliness and insufficiency if first in place, especially in more difficult OHCA cases.

The aftermath

The aftermath was the time period from when the FRs left the scene, and as long as vivid memories of the cardiac arrest were recalled and could be recounted by the participants.

Caring for the rescuers

After tough assignments bodily symptoms, spinning thoughts and imprinted memories were reported in terms of ‘never forgetting’ (P2), and ‘stuck in my head’. (P5)

//…and I just have to pass by the place, I don’t think there has ever been a time when I haven’t thought about it, I mean, every time I walk past or drive past this place, I think about this.…// (P6)

Assessment and defusing afterwards occurred more often among equal colleagues rather than meetings initiated by superior officers. Inputs from others about the case and own performance were considered positive and could ease the pressure, but several FRs called for a more pronounced responsibility from the heads of the department. The participants expressed that occupational stress could be avoided if stress management took place regularly. Repression was a strategy for coping by some FRs, others thought this could cause long-term impairment of the ability to feel empathy. A positive experience afterwards was if the survivor came to visit the FRs at the fire station or police station. The survivors were seen as reminders of success.

Discussion

The aim of this interview study was to explore FRs experiences of participating in a dual dispatch programme in case of suspected OHCA. Our analysis of recounted critical incidents revealed three distinct time sequences regarding the cardiac arrest event described by the participants (figure 1). Our main findings in each time sequence were: (1) lack of information from EMCC about the victim caused frustration among FRs; (2) perceived uncertainty in performing CPR, especially concerning rescue breaths. To handle psychological reactions among bystanders after an OHCA could be overwhelming; (3) FRs were missing discussion after mission with participating colleagues and superior officers, especially after tough cases.

Information deficit from EMCC was a main concern for the FRs. However, information could be missing for the dispatchers in time for call-out due to language barriers or difficulties detecting if it is a true cardiac arrest or not.21 22 EMS personnel have previously described similar concerns regarding dispatch.23

Uncertainty could emerge if it was not an OHCA, but seizures or intoxication, for example. Both firefighters and police officers therefore expressed a need of more thorough education in first aid. Regular training and education is also a matter of concern in EMS organisations taking care of OHCA victims.24 Handling the airway appears to be a subject for improvement as reported earlier.14 The ERC guidelines recommend that all rescuers trained and able to perform CPR should combine chest compressions and rescue breaths.18 However, only five (50%) of the police officers had undergone annual training in CPR, and they expressed that chest compression-only technique was preferred as an easier way of managing the situation (table 2). The police force in Stockholm County joined the dual dispatch programme later compared with the firefighters, therefore the police officers have less experience in participating in cardiac arrest alarms.25 In the interviews the police officers expressed more doubts about their self-efficacy26 than the firefighters, especially concerning technical skills. To attach defibrillation pads and deliver countershocks was not much discussed by the police officers. This could be a consequence of the police being last summoned in OHCA alarms due to technicalities in the dispatch system. Other personnel prior to the police patrol have often already started treatment. In comparison, 686 firefighters in a survey, 24% had never applied an AED and 3% felt very uncomfortable doing so.27 Application rates and retention could improve if FRs underwent frequent targeted hands-on AED training.28 29 Stressful cardiac arrest situations were described in detail, despite a lapse of several months or years since the events. Adverse psychological effects after long-term exposure of traumatic events such as stress, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder has been reported among FRs.30–32 Several of the FRs discussed the need to ventilate the case among colleagues, and also the absence of organised case discussions after the mission.

A limitation of the study was that all participants worked in the most densely populated County in Sweden with high access to prehospital resources. Including FRs from other parts of the country would probably have generated other experiences, especially in low-density populated areas where there are few rescuers available. Only one of the firefighters was female, which could have affected the results. The uneven gender distribution reflects the fact that only 5.5% of all firefighters in Sweden are women.33 The police officers had a more evenly gender distribution.

Selecting volunteers for interviews could have introduced bias in terms of a non-representative sample. Different fire stations and police stations around the County were thus chosen, as well as gender and varying ages among participants to obtain as rich information as possible about the research subject. There is always a risk of recall bias in interview studies, especially if the incident took place months or years ago. All participants had however very clear memories of the recounted OHCA situations, and could describe them in detail.

In a qualitative study generalisation is not possible; instead the concept of trustworthiness is highlighted. Credibility was obtained by peer debriefing of all steps in the analysis (EJ-A, PN). The interviews were all conducted by the first author (IH-A), which increased the likelihood they were performed in the same way. The participants were recruited through different approaches to reflect a representative sample of FRs in the County, thus increasing the transferability. Moreover, the research group has experiences in cardiology, OHCA, dual dispatch (PN, LS, JH) and other domains such as intensive care and qualitative studies (EJ-A). This strengthens the results, but also raises questions about reflexivity and bias, which were discussed during the whole process of collecting and interpreting data.

Conclusion

Participating in dual dispatch in case of a suspected OHCA was often described as a complex process by FRs. Detailed information about the case and the location was crucial for the preparedness, and information deficits caused stress and incorrect perceptions about the victim. Technical challenges of performing CPR and managing the airway was prominent. The need of regular team training and education in first aid was requested as well as knowledge about psychological reactions among bystanders after an OHCA. Providing case discussions and opportunities to give and receive feedback about the case is a main task for the leadership in the FR organisations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating firefighters and police officers.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was designed by IH-A and EJ-A. IH-A recruited the participants and collected the data under the supervision of EJ-A. IH-A, EJ-A and PN made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data. IH-A drafted the manuscript. EJ-A, PN, LS and JH critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding: Financial support has been granted from The Laerdal Foundation in Norway, the Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation and Stig Holmberg Scholarship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (registration number 2015/1091-31/5).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Bækgaard JS, Viereck S, Møller TP, et al. The effects of public access defibrillation on survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review of observational studies. Circulation 2017;136:954–65. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Myerburg RJ, Fenster J, Velez M, et al. Impact of community-wide police CAR deployment of automated external defibrillators on survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2002;106:1058–64. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000028147.92190.A7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hawkins SC, Shapiro AH, Sever AE, et al. The role of law enforcement agencies in out-of-hospital emergency care. Resuscitation 2007;72:386–93. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hansen CM, Kragholm K, Granger CB, et al. The role of bystanders, first responders, and emergency medical service providers in timely defibrillation and related outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: results from a statewide registry. Resuscitation 2015;96:303–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Becker L, Husain S, Kudenchuk P, et al. Treatment of cardiac arrest with rapid defibrillation by police in King County, Washington. Prehosp Emerg Care 2014;18:22–7. 10.3109/10903127.2013.825353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hollenberg J, Riva G, Bohm K, et al. Dual dispatch early defibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the SALSA-pilot. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1781–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nordberg P, Jonsson M, Forsberg S, et al. The survival benefit of dual dispatch of EMS and fire-fighters in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest may differ depending on population density – a prospective cohort study. Resuscitation 2015;90:143–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Axelsson A, Herlitz J, Fridlund B. How bystanders perceive their cardiopulmonary resuscitation intervention; a qualitative study. Resuscitation 2000;47:71–81. 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00209-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weslien M, Nilstun T, Lundqvist A, et al. When the unreal becomes real: family members' experiences of cardiac arrest. Nurs Crit Care 2005;10:15–22. 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2005.00094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ann-Britt T, Ella D, Johan H, et al. Spouses' experiences of a cardiac arrest at home: an interview study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010;9:161–7. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Møller TP, Hansen CM, Fjordholt M, et al. Debriefing bystanders of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is valuable. Resuscitation 2014;85:1504–11. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Malta Hansen C, Rosenkranz SM, Folke F, et al. Lay Bystanders' perspectives on what facilitates cardiopulmonary resuscitation and use of automated external defibrillators in real cardiac arrests. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6 10.1161/JAHA.116.004572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elmqvist C, Brunt D, Fridlund B, et al. Being first on the scene of an accident - experiences of ‘doing’ prehospital emergency care. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:266–73. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davies E, Maybury B, Colquhoun M, et al. Public access defibrillation: psychological consequences in responders. Resuscitation 2008;77:201–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flanagan JC. The critical incident technique. Psychol Bull 1954;51:327–58. 10.1037/h0061470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methhodology. Thousands Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publcations, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lindstrom V, Bohm K, Kurland L. Prehospital care in Sweden. from a transport organization to advanced healthcare. Notf Rett Med 2015;18:107–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perkins GD, Handley AJ, Koster RW, et al. European resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 2. adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation. Resuscitation 2015;95:81–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schluter J, Seaton P, Chaboyer W. Critical incident technique: a user’s guide for nurse researchers. J Adv Nurs 2008;61:107–14. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04490.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ek B, Svedlund M. Registered nurses' experiences of their decision-making at an emergency medical dispatch centre. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1122–31. 10.1111/jocn.12701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berdowski J, Beekhuis F, Zwinderman AH, et al. Importance of the first link: description and recognition of an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in an emergency call. Circulation 2009;119:2096–102. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sundström BW, Dahlberg K. Being prepared for the unprepared: a phenomenology field study of Swedish prehospital care. Journal of Emergency Nursing 2012;38:571–7. 10.1016/j.jen.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Larsson R, Engström Åsa. Swedish ambulance nurses' experiences of nursing patients suffering cardiac arrest. Int J Nurs Pract 2013;19:197–205. 10.1111/ijn.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nordberg P, Hollenberg J, Rosenqvist M, et al. The implementation of a dual dispatch system in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is associated with improved short and long term survival. Eur Heart J 2014;3:293–303. 10.1177/2048872614532415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191–215. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lerner EB, Hinchey PR, Billittier AJ. A survey of first-responder firefighters' attitudes, opinions, and concerns about their automated external defibrillator program. Prehosp Emerg Care 2003;7:120–4. 10.1080/10903120390937229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Woollard M, Whitfield R, Newcombe RG, et al. Optimal refresher training intervals for AED and CPR skills: a randomised controlled trial. Resuscitation 2006;71:237–47. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Greif R, Lockey AS, Conaghan P, et al. European resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 10. education and implementation of resuscitation. Resuscitation 2015;95:288–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Conn SM, Butterfield LD. Coping with secondary traumatic stress by general duty police officers: practical implications. CJC-RCC 2013;47:272–98. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levy-Gigi E, Richter-Levin G, Kéri S. The hidden price of repeated traumatic exposure: different cognitive deficits in different first-responders. Front Behav Neurosci 2014;8:281 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Skeffington PM, Rees CS, Mazzucchelli T. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder within fire and emergency services in Western Australia. Aust J Psychol 2017;69:20–8. 10.1111/ajpy.12120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Swedish civil contingencies Agency. gender equality in numbers, 2017. Available: https://www.msb.se/sv/Insats-beredskap/Jamstalldhet-mangfald/Jamstalldhet-i-siffror/ [Accessed 1 Apr 2019].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.