Abstract

Introduction

The economic and health burden of sexually transmitted and genital infections (henceforth, STIs) in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) is substantial. Left untreated, STIs during pregnancy may result in several adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes. Timely diagnosis and treatment at point-of-care (POC) can potentially improve these outcomes. Despite the availability and promotion of POC diagnostics for STIs as a key component of antenatal care in LMICs, their widespread use has been limited, owing to the high economic costs faced by individuals and health systems. To date, there have been no systematic reviews which explore the cost or cost-effectiveness of POC testing and treatment of STIs in pregnancy in LMICs. The objective of this protocol is to outline the methods that will compare, synthesise and appraise the existing literature in this domain.

Methods and analysis

We will conduct literature searches in MEDLINE, Embase and Web of Science. To find additional literature, we will search Google Scholar and hand search reference lists of included papers. Two reviewers will independently search databases, screen titles, abstracts and full texts; when necessary a third reviewer will resolve disputes. Only cost and cost-effectiveness studies of POC testing and treatment of STIs, including syphilis, chlamydia, trichomonas, gonorrhoea and bacterial vaginosis, in pregnancy in LMICs will be included. Published checklists will be used to assess quality of reporting practices and methodological approaches. We will also assess risk of publication bias. Interstudy heterogeneity will be assessed and depending on variation between studies, a meta-analysis or narrative synthesis will be conducted.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required as the review will use published literature. The results will be published in a peer-reviewed open source journal and presented at an international conference.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018109072.

Keywords: point-of-care, sexually transmitted infections, genital infections, cost-effectiveness, costs, pregnancy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to synthesise evidence on the costs and cost-effectiveness of point-of-care testing and treatment of common and curable sexually transmitted and genital infections in pregnancy in low-income and middle- income countries.

This review will assess the completeness of reporting practices and identify areas for improvement in the field.

If the interstudy heterogeneity of results may prevent a meta-analysis, we will conduct a narrative synthesis of findings.

The review is limited to how studies empirically depict costs and cost-effectiveness.

The review is limited to studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

Introduction

Globally, the growing burden of common curable sexually transmitted and genital infections such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, trichomonas and bacterial vaginosis (henceforth, STIs) is alarming. The majority of infections occur in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 WHO estimated that in 2012 there were 357.4 million new cases of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichomonas.2 Left untreated, these STIs can have adverse effects on sexual and reproductive health, neonatal and child health.3–5 During pregnancy, untreated STIs are associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes, including miscarriage, preterm delivery, stillbirth, low birth weight, neonatal death and neonatal eye and respiratory infections following intrapartum transmission.6–11

There is strong evidence to suggest that the detection and treatment of HIV and syphilis early in pregnancy reduces adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes.12–15 Several studies have indicated that the early detection and treatment of STIs, such as chlamydia, trichomonas and gonorrhoea, in pregnancy could reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes.16 17 However, despite high prevalence rates in LMICs few studies in these settings investigate the detection and treatment of common, curable STIs early in pregnancy to prevent adverse outcomes. This is largely because up until recently the accurate detection of these STIs in pregnancy required laboratory-based testing, which is a relatively expensive form of diagnosis in LMICs.18 Other factors include poor infrastructure, limited human resources and high operational costs.19 20As a result, clinicians in many LMICs rely on the WHO-endorsed strategy of syndromic management to diagnose and treat symptomatic STIs, which is based on presentation of clinical symptoms and signs without laboratory confirmation.18 19 21 This strategy has limited specificity for accurate diagnosis, particularly among pregnant women where asymptomatic infections are common.19 22

Advances in STIs detection have played a key role in improving diagnosis and subsequent treatment in LMICs. The widespread adoption of point-of-care (POC) testing for HIV and syphilis, is perhaps a signal of this.23 These tests allow patients to be tested, diagnosed and treated in a single visit to a health facility.24 There is evidence that suggests the introduction of POC tests for HIV and syphilis at antenatal clinics has reduced the rate of perinatal and infant morbidity and mortality in many LMICs.25 26 This evidence, however, cannot single-handedly drive the implementation of STIs screening programmes. POC testing also presents a particularly challenging scenario. On the one hand, the unit cost-per-test is higher owing to the loss of economies of scale offered by automation, typically by centralised laboratories. On the other hand, it offers the potential of substantial savings through enabling the rapid delivery of results and treatment, avoiding the need for recall and loss of patients requiring treatment, and the associated reduction of facility costs.27 28 Economic evaluations provide evidence on the relative cost-effectiveness of implementation and can help address these considerations and inform resource allocation. While the number of studies analysing the cost and cost-effectiveness of POC testing and treatment of STIs in pregnancy in LMICs is increasing, there have been no systematic reviews synthesising this body of literature.

The objective of this protocol is to identify, compare, synthesise and appraise the existing evidence on the costs and cost-effectiveness of POC testing and treatment of common, curable STIs (namely, chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, trichomonas and bacterial vaginosis) in pregnancy in LMICs. The specific objectives of this review are:

Identify and synthesise the evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of POC testing and treatment for STIs in pregnancy in LMICs.

Compare and contrast the key findings from existing literature on the cost and cost-effectiveness of POC testing and treatment for STIs in pregnancy in LMICs.

Identify the key drivers of costs and cost-effectiveness of POC testing and treatment for STIs in pregnancy in LMICs.

Appraise the quality of reporting and methodological approaches of using published checklists.

Methods

Study type, participants and intervention

The systematic review will only consider peer-reviewed cost and cost-effectiveness analyses of POC testing and treatment of STIs. We define a POC test as a diagnostic tool that requires only one visit, where the test is conducted and the result is received at the same visit. The test is simple, accurate (both specific and sensitive) and non-invasive, it is user-friendly, compact, durable and sturdy.24 Specifically, the review will include studies that focus on POC testing and treatment of common, curable STIs, namely syphilis, chlamydia, trichomonas gonorrhoea and bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women. Only studies based in LMICs, where the burden of STIs is the greatest will be included. Lastly, the review will include cost and cost-effectiveness analyses conducted within a framework of randomised controlled trials, pilot and feasibility studies and modelling studies.

Exclusion criteria

Predetermined exclusion criteria will be applied after the initial literature search. We will only include full peer-reviewed articles and exclude book chapters, commentaries, conference publications/abstracts, editorials, letters, meeting outcomes, recommendations, protocols and reviews. We will also exclude grey literature from the review. Grey literature tends to focus on study conclusions without a rigorous methodological description that could facilitate evaluating study quality. Although another limitation, during the title and abstract screening, we will exclude studies that are not in English. This reflects the language proficiency of the study team. Studies of populations other than pregnant women and on infections other than syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia, trichomonas or bacterial vaginosis will also be excluded. The focus of the studies included must be a POC test for STIs and comparators include, but are not limited to, no screening, syndromic management and existing screening programmes. We will exclude all studies not conducted in LMICs. The LMIC classification is sourced from the World Bank list comprised in 2018.29 We will not apply date and/or time of publication limitations.

Search strategy

The literature search for this systematic review will be independently conducted by two reviewers (OPMS and NB). First, OPMS and NB will independently search three preselected electronic databases, MEDLINE, Embase and Web of Science, using keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, spanning relevant subject matter. The search terms determined by OPMS, NB, LC, AV and VW, in consultation with experienced medical librarians at University College London and the University of New South Wales are presented in a condensed form in table 1. The search terms selected reflect relative search sensitivity and specificity, whereby a comprehensive search is balanced with identifying a manageable number of citations. No restrictions will be applied to the literature search. Boolean operators will be included—‘OR’ within each group of keywords and MeSH terms to indicate the areas of interest, and ‘AND’ to combine each group and find articles related to the main objective of the systematic review. Lastly, terms will be exploded and truncated where necessary.

Table 1.

Proposed keywords and MeSH terms for the literature search

| Themes | Proposed keywords and MeSH terms |

| Economic evaluations | Cost-effectiveness OR cost benefit analysis (MeSH term) OR cost analysis |

| Sexually transmitted and genital infections | Sexually transmitted infections OR Sexually transmitted Diseases OR Gonorrhoea OR Chlamydia OR Trichomonas OR Syphilis OR Bacterial Vaginosis |

| Point-of-care testing | Point-of-care testing (MeSH term) OR point-of-care OR rapid OR bedside OR near-to-patient OR test OR lateral flow OR screening |

| Pregnancy | Pregnancy OR pregnant women OR ANC OR antenatal |

MeSH, Medical Subject Headings.

OPMS and NB will then independently search for literature using Google Scholar. The first 100 results will be screened to identify additional literature, which may capture articles missed by the database searches. Finally, OPMS and NB will each conduct a hand search of references included in the final set of articles.

Data extraction and analysis

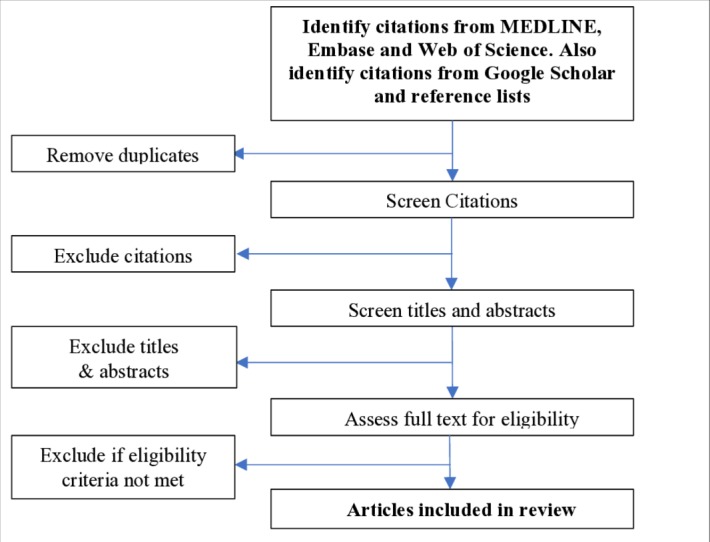

All citations found through the literature search will be exported into Endnote X8 (Thomson Reuters) and duplicates will be removed. OPMS and NB will independently screen all titles, keywords and abstracts to collate a set of articles for full-text review based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. OPMS and NB will then independently review the full texts of selected studies and apply the inclusion and exclusion criteria to compile the final set of studies to be included in the review. In the case of disputes, VW will make the final decision to include or exclude studies. Literature included in this review will be reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The screening process, illustrated in figure 1, shows the proposed PRISMA flow diagram for this review.

Figure 1.

PreferredReporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of the search selection for this systematic review.

Data will be extracted into Microsoft Excel 2013 and will include details on the authors, title, type of intervention, comparator, study setting, study design, perspective adopted, time horizon and key cost and cost-effectiveness indicators results of each study. The Drummond checklist will be used in this systematic review to assess the methodological quality of the included studies30 in conjunction with the novel Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards checklist31 to assess the consistency and transparency of reporting. The Drummond 10-item, 13-criteria checklist30 is a simplified version of the more detailed 35-item Drummond version, providing comprehensive guidance on the methodological conduct of an economic evaluation. It is recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.32 The appraisal will be independently undertaken by OPMS and NB and in case of disputes, VW will arbitrate. Careful consideration will also be given to publication bias across studies and selective reporting within studies.

Data extracted for the analysis will include primary outcomes or end points, such as total cost of the intervention, unit costs, cost-effectiveness and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (such as cost per outcome and cost per disability-adjusted life years averted), cost savings to the health system, budget impact estimates. We will also extract data on context-related factors, such as factors included in sensitivity analyses that could affect the costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions. This will allow us to explore a wide range of intervention programmes, economic evaluation methods, costs and outcomes and to identify and discuss the variation in drivers of costs and cost-effectiveness. A high degree of heterogeneity in the primary studies is anticipated—including differences in cost-effectiveness outcomes, study designs and health interventions and comparators—which will limit our ability to conduct a meta-analysis. If methodological heterogeneity is confirmed then a descriptive summary and narrative synthesis will be undertaken. Furthermore, if a subset of studies have comparable cost-effectiveness outcomes, and the sample is large enough to do a rigorous meta-analysis this will be conducted using Stata IC V.14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Study dates

This study is ongoing; the anticipated date of completion is 31 December 2019.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not directly involved in the development of this systematic review protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

The results of this review will be published in a peer-reviewed, open access journal and presented an international conference.

Discussion

Common, curable STIs in pregnancy have multiple adverse effects and left untreated can be harmful to both mothers and babies. LMICs have the highest burden of STIs, highlighting the need for affordable and cost-effective screening interventions in these settings. Collating current evidence on costs and cost-effectiveness of POC testing and treatment of STIs in pregnancy is an important first step in understanding the value of these tests in highly resource-constrained health systems. It also provides an opportunity to gauge the quality of reporting conventions used in the different studies. To our knowledge, this represents the first systematic review on this topic.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: OPMS drafted the manuscript, while initial revisions were provided by NB, AV and VW. RA, CL and WP provided feedback and revisions to the manuscript. All authors read, provided feedback on and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: WANTAIM is a partnership of academic and governmental institutions in Papua New Guinea, Australia and Europe. The trial is funded by a Joint Global Health Trials award from the UK Department for International Development, the UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (MR/N006089/1); a Project Grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (GNT1084429) and a Research for Development award from the Swiss National Science Foundation (IZ07Z0_160909/1). All employee institutions listed by the Investigators contributed through provision of facilities and/or salary contributions. In addition, OPMS and RA are supported by The University of New South Wales Scientia Higher Degree Candidate Scholarship Scheme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This systematic review does not use individual personal data and therefore does not require ethical committee approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. WHO Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the importance of a renewed commitment to STI prevention and control in achieving global sexual and reproductive health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2012: 8. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klausner JD, Broutet N. Health systems and the new strategy against sexually transmitted infections. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:797–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30361-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adachi K, Nielsen-Saines K, Klausner JD. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy: the global challenge of preventing adverse pregnancy and infant outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Biomed Res Int 2016. 10.1155/2016/9315757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newman L, Kamb M, Hawkes S, et al. . Global estimates of syphilis in pregnancy and associated adverse outcomes: analysis of multinational antenatal surveillance data. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001396 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hook EW. Syphilis. The Lancet 2017;389:1550–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32411-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2016: 54. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mullick S, Watson-Jones D, Beksinska M, et al. . Sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy: prevalence, impact on pregnancy outcomes, and approach to treatment in developing countries. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:294–302. 10.1136/sti.2002.004077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blas MM, Canchihuaman FA, Alva IE, et al. . Pregnancy outcomes in women infected with Chlamydia trachomatis: a population-based cohort study in Washington state. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:314–8. 10.1136/sti.2006.022665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cotch MF, Pastorek JG, Nugent RP, et al. . Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. The vaginal infections and prematurity Study Group. Sex Transm Dis 1997;24:353–60. 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donders GG, Desmyter J, De Wet DH, et al. . The association of gonorrhoea and syphilis with premature birth and low birthweight. Sex Transm Infect 1993;69:98–101. 10.1136/sti.69.2.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gravett MG, Nelson HP, DeRouen T, et al. . Independent associations of bacterial vaginosis and Chlamydia trachomatis infection with adverse pregnancy outcome. JAMA 1986;256:1899–903. 10.1001/jama.1986.03380140069024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawkes S, Matin N, Broutet N, et al. . Effectiveness of interventions to improve screening for syphilis in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:684–91. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70104-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Kamb M, et al. . Lives saved tool supplement detection and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy to reduce syphilis related stillbirths and neonatal mortality. BMC Public Health 2011;11 Suppl 3:S9 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moodley T, Moodley D, Sebitloane M, et al. . Improved pregnancy outcomes with increasing antiretroviral coverage in South Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:35 10.1186/s12884-016-0821-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bramley D, Graves N, Walker D. The cost effectiveness of universal antenatal screening for HIV in New Zealand. AIDS 2003;17:741–8. 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Folger AT. Maternal Chlamydia trachomatis infections and preterm birth:the impact of early detection and eradication during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:1795–802. 10.1007/s10995-013-1423-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matson SC, Pomeranz AJ, Kamps KA. Early detection and treatment of sexually transmitted disease in pregnant adolescents of low socioeconomic status. Clin Pediatr 1993;32:609–12. 10.1177/000992289303201010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. WHO Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections. WHO, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vallely LM, Toliman P, Ryan C, et al. . Performance of syndromic management for the detection and treatment of genital Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Trichomonas vaginalis among women attending antenatal, well woman and sexual health clinics in Papua New Guinea: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018630 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peeling RW, Holmes KK, Mabey D, et al. . Rapid tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the way forward. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82 Suppl 5:v1–6. 10.1136/sti.2006.024265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hawkes S, Morison L, Foster S, et al. . Reproductive-tract infections in women in low-income, low-prevalence situations: assessment of syndromic management in Matlab, Bangladesh. The Lancet 1999;354:1776–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02463-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Romoren M, Sundby J, Velauthapillai M, et al. . Chlamydia and gonorrhoea in pregnant Batswana women: time to discard the syndromic approach? BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:27 10.1186/1471-2334-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swartzendruber A, Steiner RJ, Adler MR, et al. . Introduction of rapid syphilis testing in antenatal care: a systematic review of the impact on HIV and syphilis testing uptake and coverage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;130 Suppl 1:S15–21. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. WHO Point-Of-Care diagnostic tests (POCTs) for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/rtis/pocts/en/ [Accessed 19 Nov 2018].

- 25. Mabey DC, Sollis KA, Kelly HA, et al. . Point-Of-Care tests to strengthen health systems and save newborn lives: the case of syphilis. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001233 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garcia P, Peeling R, Mabey D, et al. . S14.2 The CISNE Project: Implementation of POCT For Syphilis and HIV in Antenatal Care and Reproductive Health Services in Peru. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89:A21.1–21. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051184.0066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Toskin I, Blondeel K, Peeling RW, et al. . Advancing point of care diagnostics for the control and prevention of STIs: the way forward. Sex Transm Infect 2017;93:S81–8. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cristillo AD, Bristow CC, Peeling R, et al. . Point-Of-Care sexually transmitted infection diagnostics: proceedings of the StAR sexually transmitted Infection-Clinical trial group programmatic meeting. Sex Transm Dis 2017;44:211–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Group, T.W.B Low and middle income country classification, 2018. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/low-and-middle-income?view=chart [Accessed 19 Nov 2018].

- 30. Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. BMJ 1996;313:275–83. 10.1136/bmj.313.7052.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. . Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)--explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health 2013;16:231–50. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shemilt I, Mugford M, Drummond M, et al. . Economics methods in Cochrane systematic reviews of health promotion and public health related interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:55 10.1186/1471-2288-6-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.