Abstract

Objective

To investigate timely access to palliative medicines/drugs (PMs) from community pharmacies to inform palliative care service delivery.

Design

Mixed methods in two sequential phases: (1) prospective audit of prescriptions and concurrent survey of patients/representatives collecting PMs from pharmacy and (2) interviews with community pharmacists (CPs) and other healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Setting

Five community pharmacies in Sheffield, UK and HCPs that deliver palliative care in that community.

Participants

Phase 1: five CPs: two providing access to PMs within a locally commissioned service (LCS) and three not in the LCS; 55 patients/representatives who completed the survey when accessing PMs and phase 2: 16 HCPs, including five phase 1 CPs, were interviewed.

Results

The prescription audit collected information on 75 prescriptions (75 patients) with 271 individual PMs; 55 patients/representatives (73%) completed the survey. Patients/representatives reported 73% of PMs were needed urgently. In 80% of cases, patients/representatives received all PMs on the first pharmacy visit. One in five had to travel to more than one pharmacy to access PMs. The range of PMs stocked by pharmacies was the key facilitating factor. CPs reported practical issues causing difficulty keeping PMs in stock and playing a reactive role with palliative prescriptions. Confidentiality concerns were cited by other HCPs who were reluctant to share key patient information proactively with pharmacy teams. Inadequate information transfer, lack of CP integration into the care of palliative patients and poor HCP knowledge of which pharmacies stock PMs meant patients and their families were not always able to access PMs promptly.

Conclusions

Consistent routine information transfer and integration of pharmacy teams in the care of palliative patients are needed to achieve timely access to PMs. Commissioners of PM access schemes should review and monitor access. HCPs need to be routinely made aware and reminded about the service and its locations.

Keywords: palliative care, community pharmacy services, pharmacists, prescriptions, interprofessional issues

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first published study to identify the relative impact of factors contributing to non-timely access to palliative medicines/drugs.

This paper is the first in the UK to examine perspectives of different healthcare professionals on factors supporting and hindering access to palliative medicines/drugs.

The study is also novel in its examination of customer experience of accessing palliative medicines/drugs and the survey achieved a high response rate.

The study is possibly limited by the low number of sites but adds value to the literature in terms of barriers that need to be considered if more timely access to palliative medicines/drugs is to be more widely implemented.

Introduction

Palliative care is a holistic approach that seeks to improve the quality of life of patients with life-limiting or life-threatening illnesses.1 Population ageing together with an increase in those dying with cancer and non-communicable diseases will increase the need for palliative care at the end of life2 with predictions suggesting end-of-life care provision in the community and care homes needs to double by 2040.3 While the phrase ‘end of life’ is not precisely defined, it is commonly used in UK policy and professional guidance to refer to the final year of life.4 Nevertheless, for many people, end-of-life care will encompass a much shorter timescale and timely access to medicines for pain and symptom management, which are referred to in this study as palliative medicines/drugs (PMs), will be a crucial aspect of palliative care service delivery.4

For most patients in primary care, the source of medicines is from their community pharmacy (retail pharmacy or ‘chemist shop’); however, previous research and service audits show access to medicines such as injectable medicines used for symptom control in palliative care towards the end of life may not be as timely as patients and their families may need and wish.5–9 Pharmacies cannot stock every possible PM; local formularies, which provide lists of preferred medicines to support symptom management towards the end of life, help address this in the UK.7 8 However, knowledge on which PMs are listed in the formulary and those pharmacies holding stocks may be lacking among prescribers,7 8 which could lead to prescriptions being issued for ‘non-formulary’ items not on the local list and/or prescriptions being presented to pharmacies that do not routinely hold PMs.5–12 Delays may also be caused by legal errors on controlled drug (CD) prescriptions that do not comply with UK government legislation necessitating the pharmacist making professional and ethical judgements in supporting patient care especially in the out-of-hours period.5 7 8 There is a suggestion that handwritten prescriptions may be particularly problematic due to higher prescription error rate and out-of-hours presentation7 13 14 and they are still in use in the UK for home visits.5 7 14

Australian research on a proposed core set of PMs found that pharmacies stocked on average three out of the list of 12,11 while a system analysis in Ireland found that not stocking PMs in the pharmacy was the most likely factor leading to delays10 and this has also been found in the UK.5 7 8 12 Reported contributory factors include: the unpredictable nature of PM prescription requests; national stock shortages; the prescription of PMs or strengths not on the recommended list; unlicensed medicines; errors on CD prescriptions and the inability to contact the prescriber, for instance, outside general practitioner (GP) (family doctor) practice opening hours.5 8 14

Community pharmacies may take part in local or nationally commissioned services to support access to PMs in the community. In England, a locally commissioned service (LCS) can be provided by the local clinical commissioning group (CCG) or a local enhanced service (LES) can be commissioned by National Health Service (NHS) England Area Teams in response to public need.15 Such services differ across geographical regions and are not commissioned from all pharmacies, causing confusion for patients and their caregivers who are often involved in prescription collection and medicines management when a patient’s condition deteriorates.9 16–18 Furthermore, a lack of monitoring of PM availability against those prescribed both within the pharmacy and by the commissioning body could mean PMs are not available when needed. (Aslett, M. and Wall-Hayes, L. 2015. ‘Access to palliative drugs—community pharmacy scheme—audit.’ Unpublished NHS audit report, Birmingham, UK).

There is little research internationally on community pharmacists’ (CPs) involvement in supporting timely access to PMs. Hence, this study seeks to answer the question ‘What barriers are encountered by community pharmacists in delivering timely access to palliative care medicines.’ Due to the dearth of published research particularly in the context of community pharmacy services in England, the aim of this study was to evaluate timely access to PMs in the community pharmacy setting and make recommendations to inform the commissioning of services and future practice. The objectives were to:

Determine the timeliness of access to PMs in the community.

Investigate the prevalence and nature of prescribing errors on prescriptions for PMs presented to community pharmacies and determine whether errors impact on access to urgent PMs.

Investigate processes for accessing PMs from pharmacies where an LCS operates including referrals when PMs are not available.

Explore the views and experiences of CPs and other stakeholders on accessing PMs from community pharmacies.

Methods

This study used mixed methods across two sequential phases (see box 1 for study overview) conducted in Sheffield, UK.

Box 1. Overview of study phases.

Phase 1

Audit of palliative prescriptions meeting inclusion criteria in participating pharmacies from May to October 2016.

Customer survey for those collecting palliative prescriptions in participating pharmacies from May to October 2016.

Phase 2

Semistructured face-to-face interviews with pharmacists participating in phase 1 and other healthcare professionals involved in palliative care in the community from September 2016 to March 2017.

Phase 1: Audit of PM supplies over 6-month data collection period. Sheffield pharmacies were recruited through e-bulletin sent by the Local Pharmaceutical Committee, fax invitation to LCS PM pharmacies (19 of the 128 in the city), and verbal invitation at a local pharmacy practice development event. CPs expressing interest in taking part were given an information leaflet and consent form via email providing further information and the study inclusion criteria. Eligible CPs participated in the LCS or usually dispensed 30 or more PM prescriptions in a month based on NHS digital prescription data for opioid analgesics and midazolam dispensed in pharmacies in the region.19 Exclusion criteria were: (1) pharmacists who had worked in the UK for less than 12 months (to ensure participants were familiar with UK and local community pharmacy services) and (2) if the company or manager did not give permission for participation. None of the interested pharmacies had to be excluded based on these criteria.

A pragmatic approach to sample size was taken; the intention was to recruit up to 15 pharmacies; however, only five CPs consented to participate, partly due to the unexpectedly low level of PM prescriptions reported. Informed consent was obtained. EJM personally visited each participating pharmacy to brief them on the project, data collection forms and answer any questions to enhance consistency of data collection.

Consenting pharmacies collected data on 30 consecutively presented prescriptions, which contained medicines likely to be prescribed for palliative care patients using criteria developed by EJM. Eligible prescriptions were for adults aged 18 years or over and included one or more of the following: a long-acting oral or transdermal strong opioid coprescribed with a short-acting opioid; fast-acting fentanyl product; prescription of subcutaneous or syringe pump PMs, specified unlicensed medicines used in palliative care, as well as any prescription issued by the palliative care team. Prescription data were collected for 6 months between May and October 2016. Pharmacy data collection forms were developed by EJM and reviewed by JDM and piloted in one community pharmacy. The form recorded anonymised prescription data including: names of medications on the prescription; whether there was a legal or non-legal error on a CD prescription and further information on how that error was resolved including whether the patient’s summary care record (SCR) was accessed to resolve an error. Legal and non-legal prescription errors were identified by the CPs and non-legal errors were classified by EJM according to criteria within the PRACtICe study.20 Further details on non-legal errors were completed on a separate form to allow EJM to verify the classification. Previous research suggested that delays may be caused by doctors prescribing products not on the community pharmacy PM list7 8 (eg, midazolam 5 mg/5 mL prescribed when midazolam 10 mg/2 mL on list) hence where prescribers issued legally correct prescriptions for products not recommended on the LCS PM list these were classified as non-legal errors. Subcutaneous items in the audit were checked by EJM against the LCS list to identify non-formulary items in both LCS and non-LCS pharmacies.

Prescriptions were classified as urgent when (1) the survey respondent stated it was urgent, (2) they included anticipatory subcutaneous medicines and/or PMs to be given by a syringe pump or (3) they were from an out-of-hours provider. The date/time a prescription was received by the pharmacy and the date/time when it was ready for collection were recorded by pharmacy staff.

Survey of patients/representatives collecting PM prescriptions. The national pharmacy contracting organisation the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee Community Pharmacy Patient Questionnaire21 was used as a basis to develop a short customer survey of experiences of patients and their representatives of collecting PM prescriptions from the community pharmacy. Questions included the perceived urgency of the prescription, the customer’s previous use of the pharmacy, whether they were the patient or the patient’s representative, whether they were able to access all required PMs, whether they had been referred to the pharmacy (eg, by another healthcare professional (HCP)) and whether they had to visit more than one pharmacy to access the PMs on the prescription. When patients/representatives indicated that not all items were available they were given the option of completing a free-text section to explain how they intended to get these items. A free-text section allowed respondents to record their answer to ‘are there any things that could have been improved to make your visit better?’ The customer survey was developed by EJM with input from JDM, AB, a hospice service user coordinator and risk manager. It was piloted in one pharmacy, further refined and piloted with patients within a hospice day centre. Pharmacy teams were provided with a written briefing on how to introduce the survey to patients/representatives. Individuals collecting prescriptions for PMs were invited to participate by pharmacy support staff or the CP depending on the pharmacy. A unique number was used to match the customer survey to the pharmacy data form to allow verification of the data and assess any discrepancies. Patients/representatives not attending the pharmacy, for example, home deliveries and care home residents, did not complete the customer survey.

Phase 2: Semistructured interviews with CPs and other HCPs involved in care of palliative patients. EJM conducted interviews with the five CPs participating in phase 1 and with a purposive sample of other HCPs involved in palliative care in the community including GPs, community specialist palliative care team, community nurses, district nurses and intermediate care team members. HCPs were invited to participate via e-bulletin, email and through gatekeepers (practice managers and team leaders). Interviews were audio recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim by EJM. The interviews explored views and experiences of accessing PMs in the community; factors that supported or hindered access and their knowledge of the LCS. The interview schedule is available on request from the authors.

Data analysis

Prescription data were entered into and analysed using IBM SPSS V.23 statistical software by EJM. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for all categorical variables with mean and SD calculated for time to process prescriptions. Crosstabs was used to check relationship between legal or clinical errors and prescription generation method.

Interview transcripts were read by EJM for content familiarisation then annotated and coded manually using a priori themes from the study objectives. Following development of an analytical framework, two over-arching themes were then used to ‘chart’ the coded data: (1) timely access to PMs, (2) the CP’s role in palliative care, using the Framework Method.22 The framework was revised and iteratively refined with CW and AB against the coded interview transcripts with emergent themes and subthemes applied across the whole data set. Summaries of data were added within the framework to capture participants’ views. Mapping and interpretation of findings compared similarities and contrasts between and across professional groups and was supported through discussion and reflection with AB and CW.

Data from both phases were then triangulated where two or more sources agreed or contrasted with each other to help explain the quantitative results of the study. Triangulation enhanced the validity and reliability of the results and enabled integration of the findings, such that it was possible to make recommendations for practice improvement and identify issues for service commissioners to consider.

Patient involvement

The study was informed by research priorities in palliative care23 and through EJM’s professional experience including discussion with patients and carers experiencing medicines access problems following admission to a hospice. The customer survey tool was developed and piloted with patients in a hospice setting.

Results

Participants in each phase of the study

Phase 1 CP audit: Participating pharmacies were diverse in that they included pharmacies classified as independent (having fewer than five branches) and multiple (having five or more branches); two provided access to PMs under an LCS and three did not. Pharmacy sites were a combination of high street/local parade of shops (3) and suburban (2) with both suburban pharmacies colocated with a GP practice. For pharmacies not consenting to take part, the main reason cited was small numbers of palliative care prescriptions dispensed in the pharmacy.

Customer survey: Customer surveys were completed against 55/75 CP audit forms; response rate 73.3%. Non-completion related primarily to home deliveries and care home prescriptions.

Phase 2 CP and other HCP Interviews: 16 individuals participated: CPs (5), GPs (3), specialist palliative care team (2), community nurses (5) and intermediate care team (1). The five CPs were also involved in phase 1. Median interview durations were 51 min for CPs and 18.5 min for GPs and other HCPs.

Phase 1: prescription characteristics

A total of 271 prescription items on 75 prescription forms was recorded (range 2–33 per pharmacy, median 14) over the 6-month audit period with a mean number of 3.6 prescription items per form. This included 68.3% (n=185) of PMs identified as urgent, 49.8% (n=135) containing subcutaneously administered PMs and 24.7% (n=67) containing subcutaneously administered CDs. In 91.1% (n=123) of cases, subcutaneous items were chosen from the LCS formulary list. Non-formulary choices were either different presentations of formulary items (5.9%, n=8) or items not on the LCS list (3.0%, n=4). Varying strengths of midazolam ampoules accounted for 41.7% (n=5) of non-formulary choices.

Prescriptions were computer generated (n=245, 90.4%) or handwritten (n=22, 8.1%), with no prescriptions delivered electronically via the electronic prescription service (EPS); missing data (n=4, 1.5%). Most prescriptions were written by NHS GPs providing in-hours services (n=233, 86%), with out-of-hours GPs (n=33, 12.2%) or specialist palliative care team (n=5, 1.8%) writing the remainder. There were no non-medical prescriber prescriptions within the sample. Prescriptions were presented to the pharmacy during GP opening hours (from 9:00 to 18:00 hours, Monday to Friday) (n=176, 64.9%) or outside GP hours (evenings and weekends) (n=77, 28.4%); missing data on 6.6% of forms (n=18).

Phase 1: prescription audit

Legal errors were present in 1.1% (n=3) of prescription items; all of which were computer generated, not specifying a dose on a CD given via infusion. There were no legal errors on handwritten prescriptions. There was insufficient evidence of a difference between the prescription generation method and legal errors (Fisher’s exact two-sided test, p=0.052). Other non-legal prescribing errors, such as incomplete information, dose/strength error, generic/brand error, allergy and quantity error, occurred in 3.0% (n=8) of items. Table 1 summarises the prevalence of different medication problems on prescriptions and table 2 indicates types of prescribing errors using categories as in the PRACtlCe study.20

Table 1.

Prevalence of medication problems

| Type of medication problem | Frequency of problem | Total no of prescription items | Percentage prevalence |

| Legal errors | 3 | 271 | 1.1 |

| Prescribing errors (see table 2) | 8 | 271 | 3.0 |

| Out of stock with supplier | 1 | 271 | 0.4 |

| Non-formulary LCS item requested | 12 | 135 | 8.9 |

LCS, locally commissioned service.

Table 2.

Prescribing errors (n=271)

| Type of prescribing error | Frequency | Percentage prevalence |

| Incomplete information on prescription | 2 | 0.7 |

| Dose/strength error | 2 | 0.7 |

| Generic/brand error | 2 | 0.7 |

| Allergy* | 1 | 0.4 |

| Quantity error | 1 | 0.4 |

*Allergy ascertained from patient or patient’s medical record on pharmacy dispensing system.

Phase 1: time to access urgent palliative care medicines

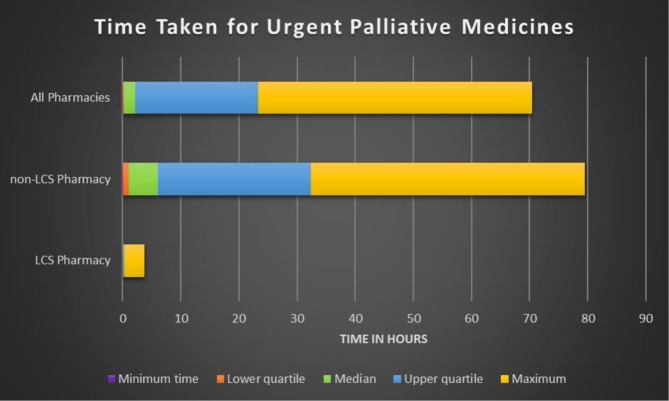

Valid time data were available for 57.8% (n=107) of 185 urgent items (n=73 missing data; n=5 excluded where PMs unavailable and prescription taken elsewhere and recorded as 0 min). Median time to process urgent PMs (time of prescription receipt to time of complete supply of PMs) was 2 hours (10 min in LCS pharmacies and 5 hours in non-LCS pharmacies). The maximum time to process urgent PMs was 3 hours and 39 min within LCS pharmacies, and 47 hours and 15 min within non-LCS pharmacies (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time taken to access urgent palliative medicines from community pharmacies . LCS, locally commissioned service.

The median time taken to access urgent medications (n=107) between pharmacies participating in the LCS and pharmacies not participating in the service was significantly different (independent samples median test p=0.002 at 95% confidence level); with pharmacies not participating in the LCS taking significantly longer than pharmacies in the LCS.

Legal errors had minimal effect on access as all urgent PMs with legal errors were available within 30 min of presentation. Legal errors were resolved by: contacting the nursing home to specify the dose to be given on a prescription for PMs via a syringe pump using a community medicines administration record, using the pharmacy patient medication record to access information on a previously issued prescription, and contacting the prescriber. The patient’s SCR was not used to resolve errors in the prescription audit sample.

Phase 1: customer survey

Survey responses showed that representatives collected PMs on behalf of the patient (65.5%); for both themselves and the patient (1.8%); and patients collected their own PMs (32.7%); 72.9% of surveys overall indicating the prescription included urgent item(s). All cases for urgent subcutaneous medications were collected by a representative on behalf of a patient. In 42.6% of cases, the patient/representative attended their usual pharmacy. Patients/representatives also indicated the pharmacy was: convenient (14.8%); one of several pharmacies used (20.4%), or that they had been referred to the pharmacy for the medications (21.8%).

In 80% of cases, patients/representatives received all medications against the prescription at the first pharmacy they visited. In 20% (11/55), one or more items on the prescription was not available, in five of these, the item(s) were urgent. Free-text sections were completed for 6 of the 11 cases of unavailable items. Four indicated that they would return to collect the item from the pharmacy and two said they would try another pharmacy to obtain the items.

Thirteen respondents made additional comments on whether their experience could have been better. Comments were mostly positive: six indicated ‘no’, ‘none’, ‘no fine’ or similar phrase; five made comments on the staff or service: ‘friendly services under difficult circumstances’, ‘no—staff really friendly and helpful, service was quick and efficient’, ‘nothing—excellent and quick service’ and one explained ‘nothing much that would make it better, but I phone in advance to make sure my items are in stock’. One respondent requested to ‘keep a stock of all required items’.

Overall one in five patients/representatives had to go to more than one pharmacy to get urgently needed PMs, increasing to one in three for urgent subcutaneous injection prescription items. One in every two patients/representatives referred to the pharmacy by another HCP had to go to more than one pharmacy. Data from the prescription audit and customer survey were triangulated to verify the validity of the information in phase 1.

Phase 2: interview findings

Findings from the interviews are presented in four sections: timely access, challenges, knowledge of LCS, and communication and collaboration. The findings are illustrated by verbatim quotes from the interviews where appropriate.

Timely access

Anticipating need and forward planning were key themes to ensure timely access to PMs.

… I could go in now and say, ‘I need these drugs’ (and the CP might say) ‘Oh I can get them in for 11 o’clock tomorrow morning’ [exasperated laugh] it’s like that’s not really very helpful, I need them now (HCP7, Community Healthcare Professional)

Community nurses and palliative care team staff reported strategies to enhance access including conducting an end of week check and balance for those on syringe pumps to ensure sufficient stock for over the weekend when fewer staff were available. Specialist palliative care team staff also described making do with the medicines already available in the house and then ordering medication for the next day. CPs perceived that patients/HCPs phoning ahead for large quantities would be helpful. Insufficient quantities of PMs could adversely impact patient symptom management and had consequences for staff resources, however, not all situations could be taken into consideration.

… a GP won’t prescribe a syringe driver ahead of time…we are always…having to do it now not in a more considered way (HCP4, Community Healthcare Professional)

… I remember having to go [to the pharmacy] in the middle of doing a [syringe] driver because there weren’t enough drugs (HCP8, Community Healthcare Professional)

The local CCG had implemented a template on the GP prescribing system to provide a ‘suite’ of PMs according to local last days of life algorithms, which included some of the injectable medicines listed on the LCS formulary. Even so, in phase 1 several ‘non-formulary’ medications not on the local CCG PM list were prescribed and in phase 2 CPs in LCS pharmacies described non-compliance with the local formulary as a reason for a lack of timely access to PMs.

We’ve got three different strengths of oxycodone injection, and they [GPs] prescribe all three, and you might not have one, you might have the other…it’s just so frustrating… (P4, Community Pharmacist)

The big problem is midazolam…so many strengths…volumes of ampoules…the GPs just pick one. (P5, community pharmacist)

Challenges

CPs described practical issues in supplying PMs, for example, stock ordering processes including: timing of deliveries and the inability to return CD items to suppliers due to legal restrictions; CD cabinet size (to meet UK legal requirements for storage) and quantities on prescriptions.

We don’t have an ability to be able to keep a lot [controlled drugs] and so we have a particular issue with the quantities that they write on the prescriptions sometimes which can impact on the next patient (P4, Community Pharmacist)

We’ve only got very small CD cabinets…the more controlled drugs you keep the more issues you are going to have (P1, community pharmacist)

Furthermore, patient records and charts to check opioid dose changes and syringe pumps were often not accessible to CPs.

With regards to changing doses or monitoring, I think that would be difficult for a community pharmacist. We have the summary care [record]… with palliative care the dose can change, you’ve got the pink card…sometimes we see [the pink card] and sometimes we don’t (P2, Community Pharmacist)

… they [CPs] don’t get the pink card [syringe pump chart] they simply get the prescription (HCP3, GP)

I might only need…extra diamorphine…whereas I might be using midazolam and haloperidol…but I’ve still got a supply of those, so they [CPs] don’t always know what’s in the [syringe] driver (HCP4, Community Healthcare Professional)

Knowledge of LCS

HCPs had little knowledge of either the LCS or the pharmacies commissioned to provide it but knew which pharmacies were likely to keep some PMs in stock.

I don’t know who’s commissioned we just basically know which ones we go to that are more likely to have it. (HCP4, Community Healthcare Professional)

… relatives who are running right left and centre trying to get hold of these meds…there is a commissioned service…but we don’t know who they are. (HCP1, Community Healthcare Professional)

GPs generally thought that all pharmacies kept some injectable PMs in stock but said they might ring in advance to check the medication was available if a supply was needed urgently. Non-LCS pharmacist providers knew of the service and how to refer a patient/carer if they did not have the requested medication available. Usually, they would phone ahead to the pharmacy to check the medication was available before making a referral. Being able to make a referral depended on whether the carer had access to a car.

… if they haven’t got a car it’s sometimes a bit tricky (P1, Community Pharmacist)

Communication and collaboration

Participants described strategies to enhance access to PMs. Two non-LCS pharmacies had worked with GP practices to discuss and agree to stock a subset of the LCS PMs; they had similar response times to pharmacies in the LCS.

… we went to them[GPs] and said, what are the most common drugs you would prescribe in palliative care…they [GPs] came back with a list…so we would try to keep the stock in for what they specified (P3, Community Pharmacist)

CPs reported that some patients/carers contacted the pharmacy when they ordered a prescription for a CD that might not be stocked. Community and specialist palliative care team staff described how they would suggest the pharmacist kept sufficient stock when they had someone on a syringe pump or large quantities of injectable medications. There appeared to be some examples where excellent communication and collaboration existed between GPs, HCPs and CPs, which resulted in more timely access for PMs.

… one GP…rang us and said well what have you got in stock and what can you get, which I found really, really useful because as the prescription came in the stock came in and this thing was completely seamless (P3, Community Pharmacist)

When we were down at [previous community nurse location] …there was a pharmacy next door so…if we had any quick questions, we would go and talk to them…they were more like part of the team (HCP7, Community Healthcare Professional)

However, concerns around patient confidentiality by GPs and other HCPs meant that more often this information was not shared with the pharmacy team in advance of receiving the prescription.

… but you’re limited by what you can tell them [pharmacists] obviously from a confidentiality point of view… (HCP11, Community Healthcare Professional)

We don’t communicate with them [community pharmacist] what the problem with the patient is we just prescribe the drugs… sometimes they can obviously work it out. (HCP3, GP)

I do have some slight reservations about them [pharmacists] knowing all those ins and outs…I’m not sure how wide that circle is in there [pharmacy]…I’d prefer it …on just a case by case basis…to an identified clinician… (HCP10, GP)

Discussion

The sequential use of mixed methods to first quantify the ‘problem’ and then qualitative methods to provide context to the barriers to timely supply of PMs generated new insights into a long-standing problem. Timeliness of access was found to primarily relate to a mismatch between medicines stocks held by CPs and the PMs that GPs prescribed. Legal errors on CD prescriptions played a much smaller role and had little impact on access to PMs in this study. Stock availability as a significant factor to support timely access has also been seen in previous studies.5 8 10 11

Study results appear to indicate a low prevalence of legal errors on palliative care prescriptions considering 42% of prescriptions were for CDs. Previous studies suggest that legal errors on prescriptions can range from less than 1% up to approximately 1.9%14 20 24–28 though data do not specifically focus on palliative care prescriptions. Legal errors in the current study arose on computer generated prescriptions for CDs administered by a syringe pump. The primary care organisation prescribing template for PMs may have impacted positively, minimising the number of legal errors.

Our findings of differential time to access PMs between community pharmacies participating in the LCS for PMs and non-participants indicate that a local service can enhance access. Those pharmacies working with local GP practices to keep a small agreed range of PMs in stock had similar access times to those within the LCS, suggesting that such collaboration can also support more timely access and improve patient and carer experience. Such wider collaboration has been advocated within national policy drivers and enables greater integration of pharmacy teams in improving patient care.29–32 Some HCPs considered CPs ‘part of the team’ but others saw them only in their ‘supply’ role. Together with concerns about confidentiality, this prevented many HCPs from communicating with CPs about available stock or giving advance warning to allow stock to be obtained in a more timely way. A particular concern seemed to be who else, in addition to the pharmacist, might have access to sensitive information. Commissioners could remind primary care staff of community pharmacy ethical and information governance practices to correct any misunderstandings. They could also encourage HCPs to be proactive in checking stock availability with the patient’s usual pharmacy.

Palliative patients often rely on family members and friends to support them with managing their medication especially towards the end of life.9 16–18 Our findings show that some families obtain urgently required medicines from a pharmacy different than the one that usually supplied the patient’s medicines. It is unclear what effect these changes in continuity of care between pharmacies might have towards the end of life, but this study shows that some CPs enhance access by calling other pharmacies to ascertain they have PMs in stock. A potential solution could be through CPs having read and write access to the SCR allowing them, whether they are the patient’s regular, out of hours or LCS pharmacy, to record patient care scenarios to ensure safe, continuity of care of PMs. Variable accessibility and difficulties in use of SCR by CPs33 may suggest wider access to patient records is required.

One in five patients/representatives accessing PMs had to go to more than one pharmacy. This is the first study to quantify the number of patients/representatives who had to do so, with associated inconvenience, wasted time and stress. This finding could be explained by a lack of awareness of the LCS since this is not advertised to the public and there was also low awareness among HCPs and GPs in the interviews. Monitoring of LCS/LES services by commissioners may not always be effective. One audit found only 1 of 19 pharmacies held all PMs on the formulary list and some CPs were not aware that the scheme was active. (Aslett, M. and Wall-Hayes, L. 2015. ‘Access to palliative drugs—community pharmacy scheme—audit’ Unpublished NHS audit report, Birmingham, UK). There was also evidence in phase 1 of prescriptions being written for items not on the LCS list, which would not usually be stocked in the pharmacies. Commissioners’ service audits could investigate referral patterns from pharmacies not within the LCS, furthermore monitoring of LCS pharmacies may improve practice and caregivers’ experience. Commissioners could also act to improve awareness of LCS among local HCPs.

Some limitations affect the interpretation/generalisability of the findings of this study. The small sample of participating pharmacies, missing data, reliance on CPs to identify prescriptions and confounding factors such as time of day, number and type of staff working in the pharmacy may limit interpretation of the results and introduce a degree of bias. Differences in the commissioning of access to PMs within England also may limit the findings as there is no standard service specification stating the outcomes to be measured. Furthermore, the geographical restriction with data only collected in one city could limit application to other areas including those in remote locations, with different out-of-hours providers, and access to palliative care support in the community. Nevertheless, the study adds value to the literature in terms of barriers that need to be considered if more timely access to PMs is to be more widely implemented and the methodology has enabled new insights into factors contributing to timely access.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that legal prescribing errors may now have a smaller impact on access to urgent PMs from community pharmacies compared with mismatches between stock availability and PMs prescribed. Both participation in an LCS or collaboration with local prescribers are likely to improve access to PMs.

Recommendations for future commissioning and practice

Commissioners should

Encourage GP practices to work with local pharmacies to keep a small range of PMs available.

Remind HCPs of the ethical and information governance requirements of community pharmacies and encourage early contact to check stock availability.

Involve patients and the public in designing audits of LCS.

Community pharmacies should improve their communication with HCPs around pharmacy opening times and cut-off times for same-day delivery of medicines.

Moving forward, NHS England will be supporting development and integration of CP services into primary care through its Pharmacy Integration Fund34 and this may also improve interprofessional communication and access to PMs.

Patient Involvement

The design of the study was based on EM’s experience as a clinical pharmacist including discussions with patients and their families on accessing medicines. The research question was, therefore, derived from patients’ and family carers’ experience on accessing medicines towards the end of life. A Hospice Service User Coordinator provided support with the customer survey based on their experience of conducting surveys. Furthermore, patients within a hospice day centre supported the piloting of the customer survey.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the community pharmacies, the healthcare professionals and the patients and their representatives who kindly participated in the study. Thanks also to the staff at St Luke’s Hospice, Sheffield who supported the design of the customer survey, completed transcription of the pharmacist interviews and provided overall support to the project. The authors would like to thank Jonathan Silcock, University of Bradford, for input into statistical design and Christina Wong (CW), an experienced qualitative research colleague, who piloted the interview schedules, supported qualitative data analysis and provided workplace supervision for EJM.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ejmille1

Presented at: Parts of this study have been previously presented at conferences and published as conference abstracts.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. The title and Table 2 are updated.

Contributors: EJM implemented the study, designed and piloted data collection tools, monitored data collection, wrote the analysis plan, analysed the data, wrote and piloted interview schedule, transcribed interviews, developed the thematic framework and drafted and revised the manuscript. JDM and AB supervised EJM in planning and undertaking the study including study design, development of data collection tools, data analysis, drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The funders had no input into the research design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; the writing of the paper; or the decision for publication. Funders conducted peer review of the original study design as part of the funding application.

Competing interests: EJM received research funding from Pharmacy Research UK and Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust as well as support from St Luke’s Hospice, Sheffield; JDM and AB are employees of University of Bradford, all these organisations might have an interest in the submitted work—in the previous three years. EJM is Treasurer of the Association of Supportive and Palliative Care Pharmacy. AB and JDM report grants from Pharmacy Research UK during the conduct of the study. EJM, JDM and AB are all pharmacists registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval obtained 17 December 2015 from the Chair of the Biomedical, Natural, Physical and Health Sciences Ethics Panel, University of Bradford (approval reference E493).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. World health organisation (who) who definition of palliative care. WHO, 2012. Available: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ [Accessed Sep 2019].

- 2. The World Hospice Palliative Care Association WHO global atlas on palliative care at the end of life. Available: http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care [Accessed Sep 2019].

- 3. Bone AE, Gomes B, Etkind SN, et al. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? population-based projections of place of death. Palliat Med 2018;32:329–36. 10.1177/0269216317734435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence (NICE) - End of life care for adults Quality Standard (QS13) London: NICE; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bennie M, Hudson S, Akram G, et al. Macmillan pharmacist facilitator project six month baseline report – 2010. Glasgow: University of Strathclyde, 2010. https://www.palliativecareggc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Macmillan-Report-FINAL-04-11-2010sh2MB-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller E, Morgan JD, Blenkinsopp A, et al. Are subcutaneous palliative medicines available and accessible: an out of hours (OOH) audit in Sheffield: Abstract 61 table 1. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:407.1–407. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001204.60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Savage I, Blenkinsopp A, Closs SJ, et al. 'Like doing a jigsaw with half the parts missing': community pharmacists and the management of cancer pain in the community. Int J Pharm Pract 2013;21:151–60. 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akram G, Bennie M, McKellar S, et al. Effective delivery of pharmaceutical palliative care: challenges in the community pharmacy setting. J Palliat Med 2012;15:317–21. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sheehy-Skeffington B, McLean S, Bramwell M, et al. Caregivers experiences of managing medications for palliative care patients at the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:148–54. 10.1177/1049909113482514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lucey M, McQuillan R, MacCallion A, et al. Access to medications in the community by patients in a palliative setting. A systems analysis. Palliat Med 2008;22:185–9. 10.1177/0269216307085722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tait PA, Gray J, Hakendorf P, et al. Community pharmacists: a forgotten resource for palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:436–43. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Faull C, Windridge K, Ockleford E, et al. Anticipatory prescribing in terminal care at home: what challenges do community health professionals encounter? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:91–7. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacRobbie A, Bennie M, Akram G, et al. Macmillan Rural Palliative Care Pharmacist Practitioner Project Mapping of the Current Service & Quality Improvement Plan. Glasgow: University of Strathclyde, 2013. https://www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk/Services/Documents/Palliative%20pharmacy%20project%202016/Macmillan%20RPCPP%20Project%20EXEC%20SUMMARY%2027112013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14. MacRobbie A, Harrington G, Bennie M, et al. Macmillan rural palliative care pharmacist practitioner project phase 2 report. Glasgow: University of Strathclyde, 2015. https://www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk/Services/Documents/Palliative pharmacy project 2016/MRPP Phase 2 Full Report 2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC). Locally commissioned services. PSNC, 2019. Available: https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/locally-commissioned-services/ [Accessed Sep 2019].

- 16. Todd A, Holmes H, Pearson S, et al. 'I don't think I'd be frightened if the statins went': a phenomenological qualitative study exploring medicines use in palliative care patients, carers and healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:13 10.1186/s12904-016-0086-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joyce BT, Berman R, Lau DT. Formal and informal support of family caregivers managing medications for patients who receive end-of-life care at home: a cross-sectional survey of caregivers. Palliat Med 2014;28:1146–55. 10.1177/0269216314535963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Payne S, Turner M, Seamark D, et al. Managing end of life medications at home--accounts of bereaved family carers: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:181–8. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prescribing and Medicine Team, NHS Digital Prescriptions Dispensed in the Community - Statistics for England 2007-2017. Leeds: NHS Digital, 2018: 1–86. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/prescriptions-dispensed-in-the-community/prescriptions-dispensed-in-the-community-england-2007-2017 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Avery T, Barber N, Ghaleb B, et al. Investigating the prevalence and causes of prescribing errors in general practice: The PRACtICe Study (PRevalence And Causes of prescrIbing errors in general practiCe) A report for the General Medical Council (GMC). Manchester: GMC 2012:1–187. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) Community Pharmacy Patient Questionnaire (CPPQ): PSNC,, 2019. Available: https://psnc.org.uk/contract-it/essential-service-clinical-governance/cppq/ [Accessed Sept 2019].

- 22. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palliative and end of life care Priority Setting Partnership (PeolcPSP). Putting patients, carers and clinicians at the heart of palliative and end of life care research. PeolcPSP 2015. https://palliativecarepsp.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/a812_jameslind_report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quinlan P, Ashcroft DM, Blenkinsopp A. Medication errors: a baseline survey of dispensing errors reported in community pharmacies. Int J Pharm Pract 2002;10 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2002.tb00673.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sayers YM, Armstrong P, Hanley K. Prescribing errors in general practice: a prospective study. Eur J Gen Pract 2009;15:81–3. 10.1080/13814780802705984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hawksworth GM, Corlett AJ, Wright DJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy interventions by community pharmacists during the dispensing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999;47:695–700. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00964.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen Y-F, Neil KE, Avery AJ, et al. Prescribing errors and other problems reported by community pharmacists. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2005;1:333–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shah SNH, Aslam M, Avery AJ. A survey of prescription errors in general practice. Pharm J 2001;267:860–2. [Google Scholar]

- 29. NHS England Commissioning person centred end of life care: A toolkit for health and social care. London: NHS England, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. NHS England Five Year Forward View. London: NHS England, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31. NHS England Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View. London: NHS England, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baqir W, Paes P, Stoker A, et al. Impact of an integrated pharmacy service on hospital admission costs. Clinical Pharmacist 2018;10. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robinson J. Majority of community pharmacists do not access the SCR in a typical week, analysis shows. Pharm J 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34. NHS England NHS England - Pharmacy Integration Fund. [Intranet], 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/pharmacy-integration-fund/ [Accessed Sep 2019].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.