Abstract

Background:

One of the primary cannabis-related reasons individuals seek emergency medical care is accidental cannabis poisoning. However, our understanding of the incidence and characteristics of those who receive emergency medical care due to cannabis poisoning remains limited. We address this gap by examining up-to-date information from a national study of emergency department (ED) data.

Methods:

The data source used for this study is the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS). An International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM) diagnostic code was used to identify accidental poisoning by cannabis (T40.7X1A) as specified by healthcare providers. Logistic regression was employed to examine the relationship between ED admission for cannabis poisoning, sociodemographic factors, and mental health disorders.

Results:

In 2016, an estimated 16,884 individuals were admitted into EDs in the United States due to cannabis poisoning, representing 0.014% of the total ED visits for individuals ages 12 and older. Individuals who sought care for cannabis poisoning were more likely to be young, male, uninsured, experience economic hardship, reside in urban central cities, and experience mental health disorders as compared to individuals admitted for other causes. Among cases that included the cannabis-poisoning code, many also had codes for accidental poisoning due to other substances such as heroin (4.7%), amphetamine (10.8%), cocaine (12.9%), and benzodiazepine (21.3%).

Conclusions:

Despite the limitations of ICD-10 data, findings provide new evidence suggesting that practitioners be attuned to the prevention and treatment needs of high-risk subgroups, and that screening for mental health problems should be standard practice for individuals diagnosed with cannabis poisoning.

Keywords: Cannabis, Marijuana, Poisoning, Mental Health, Drug Use, Emergency Care

1. Introduction

We live in a time of tremendous change in cannabis policy in the United States (US). Beginning with California’s approval of the Compassionate Use Act of 1996 (Bergstrom, 1997), allowing the use of cannabis for medical purposes, we have seen a steady progression of states opting to decriminalize, medicalize, and, in some cases, legalize the sale, possession, and use of cannabis (Salas-Wright and Vaughn, 2016). Indeed, while cannabis policies vary widely across jurisdictions, at present, cannabis use is only fully illegal—that is, not available for medical or recreational use nor decriminalized—in fewer than one third of US states.

As the cannabis policy landscape changes, we see compelling evidence that cannabis use among adults has increased markedly. Hasin and colleagues (2015) examined data from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) and identified a twofold increase in cannabis use between 2001/2002 and 2012/2013. Analyzing data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Compton and colleagues (2016) identified noteworthy increases in both daily and past 12-month cannabis use among adults, with changes beginning in the mid-2000’s. During the same period, we also see evidence that fewer Americans view cannabis use as risky (Jarlenski et al., 2017; Okaneku et al., 2015; Salas-Wright et al., 2017; Sarvet et al., 2018) and an increasingly large number support medicalization/legalization initiatives (Hartig and Geiger, 2018; McCarthy, 2018).

Nevertheless, leading voices in public health and addiction medicine remain steadfast that cannabis use brings with it risk of adverse health consequences. Volkow and colleagues’ (2014) argue that cannabis should not be considered a “harmless pleasure”, noting that numerous studies indicate that cannabis use can lead to myriad adverse effects such as impaired memory and motor coordination, paranoia and psychosis, and cannabis use disorder. Scholars and policymakers have continued to examine the degree to which cannabis use is related to risk of injury and hospitalization (National Academies, 2017; Zhu and Wu, 2016). One of the primary cannabis-related reasons individuals seek emergency medical care is cannabis poisoning, a condition in which individuals are made ill—often presenting with acute anxiety, intermittent loss of consciousness, or nausea—as a result of excessive use (Galli et al., 2011; Heard et al., 2017). Cannabis poisoning may be of particular concern given increasing THC levels in cannabis (Chandra et al., 2019) and the growing popularity of “edibles” that have a slower psychoactive onset than smoking/vaping (Hudak et al., 2015).

Despite increased cannabis use and concern about cannabis-related medical care, our understanding of the incidence and characteristics of those who receive emergency medical care due to cannabis poisoning remains limited. The present study aims to address this important gap by examining up-to-date, national data on more than 30 million hospital-based emergency department (ED) visits using the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS). Specifically, we present information on the demographic and mental health characteristics of individuals ages 12 and older who were admitted into an ED due to cannabis poisoning in 2016.

2. Method

2.1. Data and Sample

Data from the 2016 NEDS Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) was utilized for this analysis. NEDS is the largest, publicly available all-payer database of ED visits. The 33 million unique visits from 953 hospitals represents a 20 percent stratified sample of all hospital owned EDs in the United States. The weighted analysis allows for the calculation of national estimates, which represent 144 million ED visits (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2018). The analytic sample includes patients 12 and older discharged from the ED in 2016.

2.2. Measures

Cannabis Poisoning.

A single dichotomous International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM) (World Health Organization, 1993) diagnostic code was used to identify accidental poisoning by cannabis (Code = T40.7X1A). Here “accidental” excludes situations in which an individual intends to make themselves ill, focusing instead on poisoning resulting from unintended overconsumption, accidental use of THC-rich products, and other inadvertent poisonings. While healthcare providers have discretion in the selection of a cannabis poisoning diagnosis, symptoms that may prompt an ED visit include but are not limited to: anxiety, paranoia, and psychosis; heart palpitations, arrhythmia, or decreased blood pressure; and abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting (Cooper and Williams, 2019).

Mental Health Disorders.

Four mental health disorder categories were also identified on the basis of ICD-10-CM codes. These include psychotic (F20-F29), affective (F30-F39), anxiety (F40-F48), and behavioral and emotional disorders (F90-F98).

Demographic Variables.

We examined key demographic variables available in the NEDS, including age, gender, median household income in patient’s ZIP code, primary payer, urban-rural classification of the patient, and problems related to housing/economic circumstances (ICD-10 code Z59).

3. Analyses

First, we estimated the national incidence of ED admissions for cannabis poisoning. Using data from the US Census Bureau, as provided by AHRQ, allowed us to calculate the rate of cannabis poisoning ED admissions per 100,000 individuals in the US. Next, we employed logistic regression models to determine which covariates were associated with cannabis poisoning. We also examined differences in effect modification across gender. All estimates were weighted to account for NEDS complex sampling design using the svyset command and svy prefix in Stata 14.

4. Results

In 2016, an estimated 16,884 individuals (95% CI = 14,846-18,917) were admitted into EDs in the US due to cannabis poisoning. This constitutes a rate of 6.15 admissions per 100,000 residents in the US ages 12 and older. ED visits for cannabis poisoning represented 0.014% of the total ED visits in the NEDS. Notably, among cases that included the cannabis-poisoning code, many also had codes for accidental poisoning due to other substances such as heroin (4.75%), amphetamine (10.77%), cocaine (12.90%), and benzodiazepine (21.32%). Table 1 displays the rate of cannabis poisoning by demographic subgroup and the adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for the odds of ED admission due to cannabis poisoning (as compared to admission for other ailments). Individuals admitted for cannabis poisoning were significantly less likely— compared to those ages 12-17—to be ages 30-49 or 50 and older. Those admitted for cannabis poisoning were also more likely to be uninsured and to experience housing/economic adversity, and to reside in central cities.

Table 1.

Receipt of Emergency Department Services for ICD-10 Cannabis Poisoning Diagnosis in 2016

| ED Admissions for Cannabis Poisoning |

Odds Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Incidence / 100,000 |

AOR | (95% CI) | |

| Sociodemographic Factors (with corresponding % of sample) | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 12-17 (6.45) | 1781 | 0.55 | ref | |

| 18-29 (21.54) | 6700 | 2.07 | 1.07 | (0.93-1.24) |

| 30-49 (29.84) | 5430 | 1.68 | 0.57 | (0.47-0.69) |

| 50 and older (42.17) | 2972 | 0.92 | 0.24 | (0.20-0.28) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (42.95) | 10,929 | 3.38 | ref | |

| Female (57.05) | 5955 | 1.84 | 0.40 | (0.36-0.45) |

| Insurance Payer | ||||

| Medicaid/Medicare (53.73) | 7648 | 2.37 | ref | |

| Private Insurance (29.11) | 4341 | 1.34 | 0.88 | (0.79-0.98) |

| Uninsured (12.31) | 4044 | 1.25 | 1.60 | (1.35-1.89) |

| Other (4.86) | 831 | 0.26 | 0.92 | (0.74-1.14) |

| Housing/Economic Problems | ||||

| Yes (0.51) | 16,547 | 5.12 | 1.94 | (1.47-2.56) |

| No (99.49) | 337 | 0.10 | ref | |

| Median Household Income | ||||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) (34.98) | 5991 | 1.85 | ref | |

| Quartile 2 (27.33) | 3755 | 1.16 | 0.86 | (0.73-1.02) |

| Quartile 3 (21.01) | 3283 | 1.02 | 0.97 | (0.81-1.17) |

| Quartile 4 (highest) (16.68) | 3178 | 0.98 | 1.22 | (0.97-1.54) |

| Urban-Rural Classification | ||||

| Central City (29.58) | 6185 | 1.91 | ref | |

| Suburban (20.81) | 3247 | 1.00 | 0.75 | (0.64-0.88) |

| Small/Medium City (31.72) | 4974 | 1.54 | 0.78 | (0.62-0.98) |

| Rural (17.88) | 2078 | 0.64 | 0.63 | (0.50-0.79) |

Note: Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) adjusted for age, gender, insurance payer, housing/economic problems, household income, urban-rural classification, and mental health diagnosis. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant. ED visits for cannabis poisoning represent 0.014% of the total ED visits for individuals 12 and older included in the 2016 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample. Values presented are survey adjusted population counts.

Due to large differences in rates across gender, we also tested for effect modification and conducted stratified analyses (not shown) examining the odds of ED admission due to cannabis poisoning among male and female patients. Several salient effect modifications and differences were identified. First, with respect to age, women admitted for cannabis poisoning were significantly more likely to be adolescents (ages 12-17) than young adults (ages 18-29) (AOR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.35-2.00). In contrast, among men, those admitted for cannabis poisoning were significantly more likely to be young adults than to be adolescents (AOR=1.59, 95% CI=1.35-1.88). Second, among females, cannabis poisoning was not significantly associated with housing/economic adversity (AOR = 1.53, 95% CI = 0.76-3.10, p = 0.236); however, among males, those reporting cannabis poisoning were more than two times more likely to report problems related to housing/economic circumstances (AOR = 2.14, 95% CI=1.55-2.95). That being said, although we see different results in terms of significance among females and males, gender did not significantly modify the link between cannabis poisoning and adversity.

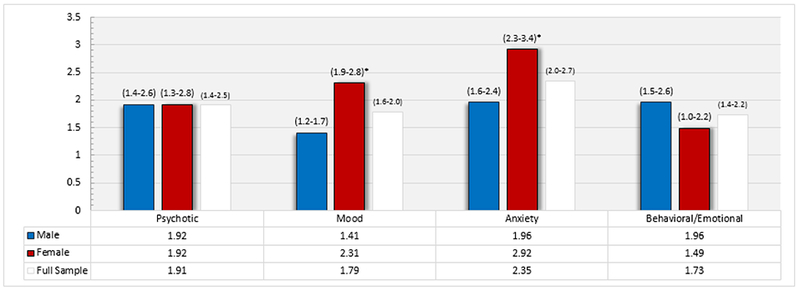

As shown in Figure 1, among the full sample of patients, those admitted to the ED for cannabis poisoning were significantly more likely to meet criteria for a psychotic, anxiety, mood, or behavioral/emotional disorder. Notably, we found that—among females—the magnitude of the association between cannabis poisoning and risk for an anxiety (AOR = 2.82, 95% CI =2.34-3.40) or mood disorder (AOR = 2.30, 95% CI = 1.90-2.79) was significantly greater than that for males (Anxiety: AOR = 1.97, 95% CI =1.63-2.37; Mood: AOR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.19-1.66). Although gender did not significantly modify the effect, the link between poisoning and behavioral/emotional disorders was slightly stronger among males (AOR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.49-2.59) than females (AOR =1.49, 95% CI= 1.02-2.17).

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for the association between ICD-10 cannabis poisoning diagnosis and mental health disorder diagnosis. AORs adjusted for age, gender, insurance payer, housing/economic problems, household income, urban-rural classification, and other mental disorders. Asterisks signify significantly different effects (p < .05) between cannabis poisoning and outcomes among the male and female samples.

5. Discussion

Findings from the present study, conducted using data from more than 30 million ED visits, provides up-to-date information on the characteristics of individuals who received emergency medical care due to cannabis poisoning in 2016. We see clear evidence that those seeking care were substantially more likely to be young, male, uninsured, experience economic hardship, and reside in central cities. Simply, we see clear evidence that risk of emergency medical care receipt for cannabis poisoning is by no means evenly distributed.

We also see compelling evidence that individuals receiving care in an ED for cannabis poisoning are more likely than other patients to experience mental health disorders. More precisely, we found that risk of mood and anxiety disorders, and childhood onset behavioral and emotional disorders, was elevated among those with cannabis poisoning. This finding is consistent with prior research indicating that rates of psychiatric problems are elevated among marijuana users (Hasin et al., 2016; Oh et al., 2017) as well as research suggesting that drug use, psychological distress, and behavioral problems are closely intertwined (Salas-Wright et al., 2016). Notably, we also found that rates of admission for cannabis poisoning were nearly two times greater among those with psychotic disorders. This too is consistent with prior research suggesting a link between cannabis use and psychosis (Hartz et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2007).

Prior research highlights differences in cannabis use across gender (see Compton et al., 2016), but prior work had not examined gender differences in cannabis poisoning. We present novel findings suggesting that gender differences observed for cannabis use extend to ED admissions for poisoning as well. Beyond the finding that men were more likely than women to be admitted to an ED for cannabis poisoning, we also found that the characteristics of male and female admissions were distinct in important ways. For one, we found that risk of mood/anxiety disorders was particularly pronounced among females admitted for cannabis poisoning. This is in keeping with prior research suggesting that cannabis use severity is more closely related to risk of depression and anxiety among women than among men (Lev-Ran et al., 2012; Patton et al., 2002). We suggest that training programs for clinical professionals emphasize these populations of elevated risk (Alford et al., 2009; Salas-Wright et al., 2018).

6. Limitations

Study findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, data are cross-sectional and, therefore, they do not allow for causal interpretation. Second, the NEDS does not provide a population-based comparison for logit models, rather we are limited to comparing differences between individuals admitted to an ED for cannabis poisoning and those admitted for other reasons. Comparisons to the general population (i.e., those who did/did not visit an ED) may provide distinct results. Third, the use of ICD-10 codes has important limitations. For instance, the ICD-10 definition of cannabis poisoning does not allow us to distinguish between intoxication, typical/normal effects of cannabis consumption, and poisoning. It is also likely that healthcare providers’ judgment in selecting the cannabis poisoning code may vary, thereby introducing uncertainty. We cannot determine the type/origin of cannabis (e.g., medical marijuana, synthetic cannabis), the mode of ingestion, and whether some cases examined represent repeated visits by the same individual. Finally, the NEDS data do not represent all cannabis-related poisonings as it only includes individuals who elected (or had someone volunteer) to take them to an ED.

7. Conclusion

The present study provides new evidence on the characteristics of individuals seeking emergency medical services for cannabis poisoning. Individuals who receive a diagnosis of cannabis poisoning are more likely to be young, male, uninsured, experience economic hardship, reside in urban central cities, and experience mental health disorders. Findings from this study suggest that practitioners be attuned to the prevention and treatment needs of high-risk subgroups, and that screening for mental health problems should be standard practice in the evaluation and treatment of those identified as experiencing cannabis poisoning. We also note that, in light of evidence that many individuals diagnosed with cannabis poisoning are also given diagnoses of poisoning for other substances (e.g., benzodiazepines), future research should examine the interconnectedness of cannabis poisoning with the use of other psychoactive drugs.

Highlights.

Sample of 33 million observations from national study of emergency departments (ED).

The rate of cannabis poisoning (CP) ED admissions is 6 in every 100,000 US residents.

CP Admission is more common among youth, males, and persons in central cities.

Individuals with CP admission are more likely to have mental health disorder.

CP admission-mental disorder link more pronounced among women than men.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01AA026645. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2018. HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- Alford DP, Bridden C, Jackson AH, Saitz R, Amodeo M, Barnes HN, Samet JH, 2009. Promoting substance use education among generalist physicians: An evaluation of the Chief Resident Immersion Training (CRIT) program. J. Gen. Intern. Med 24, 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom AL, 1997. Medical use of marijuana: A look at federal and state responses to California's Compassionate Use Act. DePaul J. Health Care Law 2, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, Church JC, Freeman TP, ElSohly MA, 2019. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008–2017). Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci 269, 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Hughes A, 2016. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002–14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 954–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD, Williams AR, 2019. Cannabis and cannabinoid intoxication and toxicity, in Montoya I, Weiss S (eds) Cannabis Use Disorders. Springer, Cham, pp 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig H, Geiger A, 2018. About six-in-ten Americans support marijuana legalization. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/10/08/americans-support-marijuana-legalization/.

- Hartz SM, Pato CN, Medeiros H, Cavazos-Rehg P, Sobell JL, Knowles JA, Bierut LJ, Pato MT; Genomic Psychiatry Cohort Consortium, 2014. Comorbidity of severe psychotic disorders with measures of substance use. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Kerridge BT, Saha TD, Huang B, Pickering R, Smith SM, Jung J, Zhang H, Grant BF, 2016. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 2012-2013: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 588–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Grant BF, 2015. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 1235–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard K, Marlin MB, Nappe T, Hoyte CO, 2017. Common marijuana-related cases encountered in the emergency department. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm 74, 1904–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudak M, Severn D, Nordstrom K, 2015. Edible cannabis-induced psychosis: intoxication and beyond. Am. J. Psychiatry 172, 911–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarlenski M, Koma JW, Zank J, Bodnar LM, Bogen DL, Chang JC, 2017. Trends in perception of risk of regular marijuana use among US pregnant and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 217, 705–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Ran S, Imtiaz S, Taylor BJ, Shield KD, Rehm J, Le Foil B, 2012. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among cannabis users: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 123, 190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J, 2018. Two in three Americans now support legalizing marijuana. https://news.gallup.com/poll/243908/two-three-americans-support-legalizing-marijuana.aspx

- Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, Lewis G, 2007. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 370, 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine., 2017. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, DiNitto DM, 2017. Marijuana use during pregnancy: A comparison of trends and correlates among married and unmarried pregnant women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 181, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaneku J, Vearrier D, McKeever RG, LaSala GS, Greenierg MI, 2015. Change in perceived risk associated with marijuana use in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila) 53, 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W, 2002. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: Cohort study. BMJ, 325, 1195–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Amodeo M, Fuller K, Mogro-Wilson C, Pugh D, Rinfrette E, Furlong J, Lundgren L, 2018. Teaching social work students about alcohol and other drug use disorders: from faculty learning to pedagogical innovation. J. Soc. Work Pract. Addict 18, 71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, 2016. The changing landscape of adolescent marijuana use risk. J. Adolesc. Health 59, 246–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Cummings-Vaughn LA, Holzer KJ, Nelson EJ, AbiNader M, Oh S, 2017. Trends and correlates of marijuana use among late middle-aged and older adults in the United States, 2002–2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 171, 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Reingle Gonzalez JM, 2016. Drug abuse and antisocial behavior: A Biosocial Life Course Approach. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Hasin DS, 2018. Recent rapid decrease in adolescents’ perception that marijuana is harmful, but no concurrent increase in use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 186, 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR, 2014. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N. Engl. J. Med 370, 2219–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 1993. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. World Health Organization, Geneva: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37108 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wu LT, 2016. Trends and correlates of cannabis-involved emergency department visits: 2004 to 2011. J. Addict. Med 10, 429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]