Abstract

A 52-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for a diagnosis of melanoma. At the time, his melanoma was excised he developed an annular, polycyclic, scaling eruption consistent with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Skin biopsy and laboratory evaluation confirmed this diagnosis. The patient had been using pantoprazole for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease for the last 3 years. The patient’s melanoma was treated surgically, and his SCLE was treated with topical steroids and hydroxychloroquine. His SCLE cleared rapidly, his steroids and hydroxychloroquine were stopped and he remains free of SCLE off of treatment. The parallel course of the patient’s SCLE and melanoma prompted consideration of SCLE as paraneoplastic to melanoma in this case. The clinical picture was complicated by the patient’s use of a proton pump inhibitor, which are common causes of drug-induced SCLE. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of possible paraneoplastic SCLE associated with melanoma.

Keywords: dermatology, drugs and medicines, rheumatology, oncology

Background

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) can rarely be a paraneoplastic phenomenon, appearing simultaneously with the onset of a cancer, resolving with successful cancer treatment and relapsing with recurrence of the malignancy, thus fulfilling McLean’s criteria for paraneoplastic dermatoses.1–6 While paraneoplastic SCLE is reported in association with many cancers, breast and lung cancer are the most commonly implicated malignancies.2–17 SCLE can be drug-induced, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be among the most common culprit medications.18 19

Case presentation

A 52 year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic after a recent diagnosis of melanoma on the skin of his right abdomen. The primary tumour was a nodular melanoma, 1.0 mm deep with eight mitoses per high power field, and a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate. Prior to presentation to our clinic, a wide local excision of the primary tumour with sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed. Radiotracer drained to lymph nodes in both axillae. The lymph node from the right axilla was positive for melanoma. The left axillary sentinel node demonstrated no malignancy. A right axillary completion lymph node dissection was performed with 30 lymph nodes removed, all negative for malignancy.

Within 1 week of his melanoma excision, he developed erythematous annular, polycyclic plaques with gray-tan scale on his trunk (figure 1). They were non-pruritic, and koebnerised around his melanoma excision scar (figure 2). He tried treating his rash with diphenhydramine for 5 days with no improvement. The patient denied arthralgias, pleuritic chest discomfort, oral ulcers, hallucinations, changes in urine colour, dark urine, hematuria, fatigue and fever. After the onset of his eruption, he developed a deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, for which he started rivaroxaban. Other than his anticoagulant and diphenhydramine, his only other medication was pantoprazole daily for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). He had been taking this for about 3 years prior to the onset of his eruption. During the first exam in our clinic, we noted a 7 mm, deep brown papule with an atypical pigment network on dermoscopy (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Annular, polycyclic erythematous plaques on the patient’s back.

Figure 2.

Note the koebnerization around the patient’s melanoma excision scar.

Figure 3.

An “ugly duckling” deep brown papule on the patient’s right shoulder. An atypical pigment network was seen on dermoscopy. The patient’s rash can also be seen.

Investigations

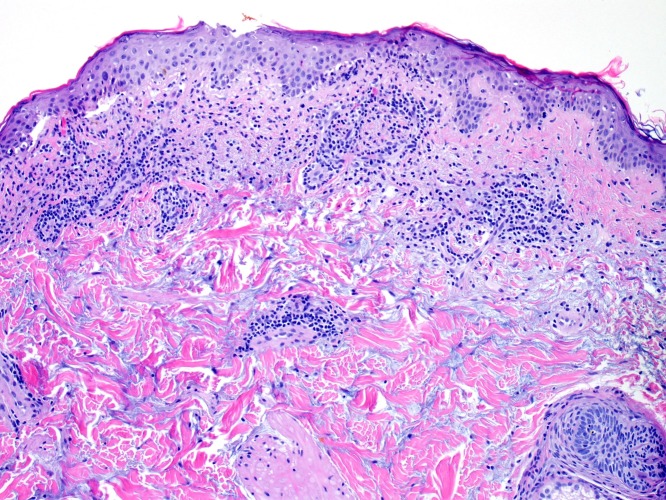

We performed biopsies of this patient’s rash as well as his new melanocytic neoplasm. The biopsy from his eruption revealed hyperkeratosis, interface dermatitis with necrotic keratinocytes and basovacuolar degeneration, a dense perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and abundant mucin deposition (figure 4). These findings are characteristic of SCLE. The patient had an antinuclear antibody of >1:1280 in a homogenous pattern.

Figure 4.

Histopathology of the patient’s rash, which demonstrates interface dermatitis with basovacuolar degeneration, necrotic keratinocytes, a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and abundant mucin deposition.

The anti-Ro52 antibody was 219 relative light units (RLU) (normal ≤20), and an anti-Ro60 antibody of >1275 RLU (normal ≤20). Anti-SS-B anti-double stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibodies were negative. A complete blood count was entirely within normal limits, as were lab evaluations of renal and hepatic function. The anti-Ro antibodies are typical of SCLE, both drug-induced and idiopathic forms. The rest of the laboratory evaluation assisted in ruling down systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

The patient’s new melanocytic neoplasm was pathologically diagnosed as a superficial spreading melanoma, 0.4 mm deep, without other high-risk histopathological features, and with a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate (figure 5). There was focal tumour regression.

Figure 5.

Pathology from the melanocytic lesion shown in figure 3. There is cellular atypia, bridging of the rete ridges, pagetoid scatter, an atypical dermal component and a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate. Tumour depth was 0.4 mm.

Differential diagnosis

The patient’s clinical presentation was typical for SCLE. His histopathological findings and laboratory evaluation were also characteristic of this disease. This patient did not meet diagnostic criteria for SLE. Due to the temporal relationship between the onset of the SCLE and his melanoma, it was considered that this may represent paraneoplastic SCLE. Other important considerations were idiopathic SCLE and drug-induced SCLE (DI-SCLE). The patient’s only medication prior to the onset of his eruption was pantoprazole, which he had been on for about 3 years. Some large studies have found PPIs to be one of the most common causes of DI-SCLE.14 15 However, this patient’s time course would have been uncharacteristic.

The melanoma biopsied from the patient’s shoulder was favoured on histopathology to represent a second cutaneous primary melanoma. However, an epidermotropic metastasis was an important differential.

Treatment

The melanoma on the patient’s shoulder was excised by the authors with 1 cm margins. His SCLE was treated with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg two times per day and triamcinolone 0.1% cream applied two times per day. Pantoprazole was not discontinued. He did not use systemic therapy such as the immune checkpoint inhibitors, nor radiotherapy.

Outcome and follow-up

By 6 months after starting hydroxychloroquine and triamcinolone, the patient’s SCLE had cleared completely. He stopped both medications at that time. At 18 months of follow-up, neither his SCLE nor his melanoma have relapsed. He continues to use pantoprazole daily. Positron emission tomography scan 6 months after presentation to us revealed no evidence of persistent or recurrent malignancy. He is still under observation by dermatology, medical oncology and surgical oncology at our institution.

Discussion

Paraneoplastic SCLE is a rare phenomenon. Cases are described that completely or partially satisfy McLean’s criteria—with simultaneous onset of SCLE and malignancy, remission of the SCLE when the malignancy is treated, and relapse of both diseases concurrently.1–6 The most common malignancies associated with paraneoplastic SCLE seem to be lung and breast cancer, but numerous other cancers have been implicated.2–17 It appears that most cases present similar to idiopathic SCLE, and most are anti-Ro antibody positive.2–17 In addition to treating the underlying malignancy, treatment approaches similar to those for idiopathic forms of cutaneous lupus can be used.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of SCLE with a possible paraneoplastic association with melanoma. Idiopathic SCLE does remain a differential diagnosis in this patient, and DI-SCLE was an important consideration at the onset of his disease. There are two factors favouring a paraneoplastic association in this case. The first is the simultaneous onset of the patient’s melanoma and SCLE. The second is the durable remission of his SCLE off all treatment in the setting of surgical treatment of his melanoma. This case does not completely fulfil McLean’s criteria for paraneoplastic dermatoses, which would require simultaneous relapse of the SCLE and melanoma.

DI-SCLE is a well-recognised phenomenon. PPIs may be one of the most common inciting drugs, and DI-SCLE can occur with all the widely prescribed PPIs.18 19 PPIs are readily available over the counter, so it is important to ask patients about over the counter medications and supplements. Histamine H2-receptor antagonists are less likely to induce DI-SCLE, and may be used to treat GORD in patients with PPI-induced SCLE.18 19 The incubation period from initiation of the drug to onset of DI-SCLE is typically about 4–5 weeks, but in some circumstances be much longer.18 20 21 Anti-Ro antibodies are often positive in DI-SCLE.18 19 Some patients with PPI-induced SCLE have developed SLE. In our patient, DI-SCLE was initially thought unlikely given the long latency period between starting his pantoprazole and the onset of his SCLE. His SCLE has not recurred despite ongoing use of his PPI. Cases of DI-SCLE and drug-induced systemic lupus have been reported with monoclonal antibodies that inhibit programmed death receptor-1 and its ligand, drugs used to treat melanoma.22–24

Learning points.

SCLE may rarely be a paraneoplastic phenomenon. This is, to our knowledge, the first reported case with an association with melanoma.

Drugs commonly induce SCLE, and proton pump inhibitors are a common culprit. Histamine H2-receptor antagonists are an alternative for these patients.

Both paraneoplastic SCLE and drug-induced SCLE present similar to idiopathic SCLE, with similar clinical and laboratory findings.

Acknowledgments

Kara Braudis, MD supervised this patient's care.

Footnotes

Contributors: JH performed the writing, editing and submission of this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McLean DI. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Arch Dermatol 1986;122:765–7. 10.1001/archderm.1986.01660190043013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michel M, Comoz F, Ollivier Y, et al. First case of paraneoplastic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with colon cancer. Joint Bone Spine 2017;84:631–3. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schewach-Millet M, Shpiro D, Ziv R, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with breast carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988;19:406–8. 10.1016/S0190-9622(88)70188-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koritala T, Tworek J, Schapiro B, et al. Paraneoplastic cutaneous lupus secondary to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Gastroinest Oncol 2015;6:E61–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mortazie M, Ramirez J, LaFond A. A case of paraneoplastic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;AB78. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fidahussein S, Sequeira H, Bois M, et al. Paraneoplastic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus as the first manifestation of small cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castanet J, Taillan B, Lacour JP, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with Hodgkin's disease. Clin Rheumatol 1995;14:692–4. 10.1007/BF02207938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Evans KG, Heymann WR. Paraneoplastic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: an underrecognized entity. Cutis 2013;91:25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dawn G, Wainwright NJ. Association between subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and epidermoid carcinoma of the lung: a paraneoplastic phenomenon? Clin Exp Dermatol 2002;27:717–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01102_4.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Torchia D, Caproni M, Massi D, et al. Paraneoplastic toxic epidermal necrolysis-like subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010;35:455–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuhn A, Kaufmann I. [Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus as a paraneoplastic syndrome]. Z Hautkr 1986;61:581–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jenkins D, McPherson T. Paraneoplastic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with cholangiocarcinoma. Australas J Dermatol 2016;57:e5–7. 10.1111/ajd.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ho C, Shumack SP, Morris D. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol 2001;42:110–3. 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chaudhry SI, Murphy L-A, White IR. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a paraneoplastic dermatosis? Clin Exp Dermatol 2005;30:655–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brenner S, Golan H, Gat A, et al. Paraneoplastic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of a case associated with cancer of the lung. Dermatology 1997;194:172–4. 10.1159/000246090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shaheen B, Milne G, Shaffrali F. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with breast carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:e480–1. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03549.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gantzer A, Regnier S, Cosnes A, et al. [Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and cancer: two cases and literature review]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2011;138:409–17. 10.1016/j.annder.2011.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aggarwal N. Drug-Induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with proton pump inhibitors. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2016;3:145–54. 10.1007/s40801-016-0067-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Linder M, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and its association with drugs: a population-based matched case-control study of 234 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol 2012;167:296–305. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marzano AV, Lazzari R, Polloni I, et al. Drug-Induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: evidence for differences from its idiopathic counterpart. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:335–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sandholdt LH, Laurinaviciene R, Bygum A. Proton pump inhibitor-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 2014;170:342–51. 10.1111/bjd.12699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu RC, Sebaratnam DF, Jackett L, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by nivolumab. Australas J Dermatol 2018;59:e152–4. 10.1111/ajd.12681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zitouni NB, Arnault J-P, Dadban A, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by nivolumab: two case reports and a literature review. Melanoma Res 2019;29:212–5. 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Michot J-M, Fusellier M, Champiat S, et al. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus following immunotherapy with anti-programmed death-(ligand) 1. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:e67 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]