Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection of the gastrointestinal tract is common in immunosuppressed patients; however, small bowel perforation from tissue-invasive CMV disease after many years of immunosuppressive therapy is a rare complication requiring timely medical and surgical intervention. We report a case of a postrenal transplant patient who presented to the emergency department with severe lower abdominal pain with CT of the abdomen/pelvis revealing a small bowel perforation. He underwent an emergent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, and his histopathology of the terminal ileum was positive for CMV disease. He was successfully treated with intravenous ganciclovir postoperatively. We discuss the pathophysiology, histopathological features and treatment of CMV infection.

Keywords: general surgery, renal transplantation, infection (gastroenterology)

Background

CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus classified as a member of the Herpesviridae family.1 In high-income countries, CMV may infect between 60% and 70% of the population but remain latent until it is reactivated to cause disseminated disease, specifically in the immunocompromised, such as in patients post-transplant, patients who underwent haemodialysis and chemotherapy, and patients with AIDS.2 3 Small bowel perforation is a rare but serious complication of disseminated CMV disease, and our management of this patient was complicated by their immunosuppressed state.

Case presentation

An independent 67-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 1-day history of sudden-onset lower abdominal pain described as severe and radiating to his back, with associated nausea and vomiting. He denied any changes to his bowel frequency and consistency. His medical background was significant for right renal transplant performed 12 years ago due to IgA nephropathy, and his immunosuppressive therapy included mycophenolate 500 mg two times per day, tacrolimus 1 mg once a day and prednisone 7.5 mg once a day. Routine colonoscopy was performed most recently 5 years ago and was reported as unremarkable. The patient appeared pale and diaphoretic. On examination, he was hypertensive (blood pressure: 190/110 mm Hg), tachycardic (heart rate: 120 beats/min) and febrile (40.2°C) with generalised abdominal tenderness and generalised peritonism.

Investigations

Preliminary blood tests revealed mild leucocytosis (white cell count: 11.2×109/L), otherwise remaining results, including haemoglobin (Hb: 129 g/L), platelets (149×109/L), liver enzymes (Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 110 IU/L, Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT) 32 IU/L, Alanine transaminase (ALT) 32 IU/L, Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 34 IU/L), international normalised ratio (1.1) and lactate (1.3 mmol/L) were inside normal limits. His creatinine was baseline (179 μmol/L). His tacrolimus trough level was 4.4 ng/mL on presentation. His blood culture and urine microscopy and culture were negative.

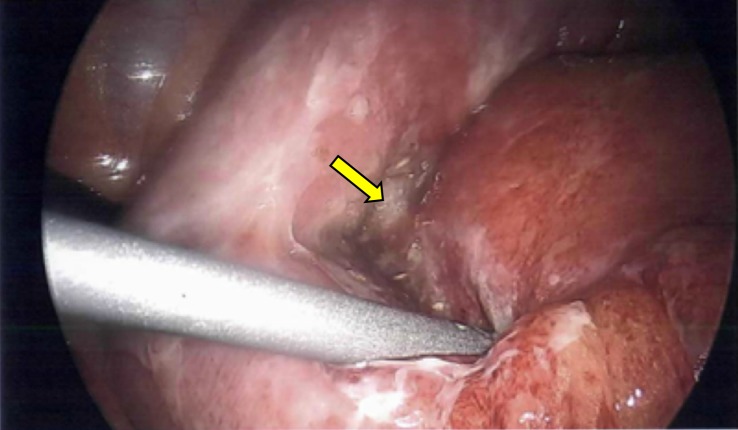

CT of the abdomen/pelvis with intravenous contrast was immediately performed, which demonstrated multiple locules of free gas in the right lower quadrant with associated thickening of the short segment of the terminal ileum and mesenteric stranding, consistent with perforation of the small bowel (figure 1). There was no hydronephrosis, periureteric or perinephric stranding in both his native and transplanted kidneys. Furthermore, given the location of the free gas, there was no evidence of acute perforated appendicitis.

Figure 1.

Presence of multiple locules of free gas in the right lower quadrant, as well as thickening of the terminal ileum (arrow) on CT of the abdomen/pelvis, was highly suggestive of small bowel perforation.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of sudden atraumatic small bowel perforation included previously undiagnosed inflammatory bowel disease, severe diverticulitis, mesenteric ischaemia and malignancy. We noted his most recent colonoscopy was unremarkable; however, this was performed 5 years ago. Furthermore, in the context of his immunosuppressed state postrenal transplant, disseminated CMV disease was considered.

Treatment

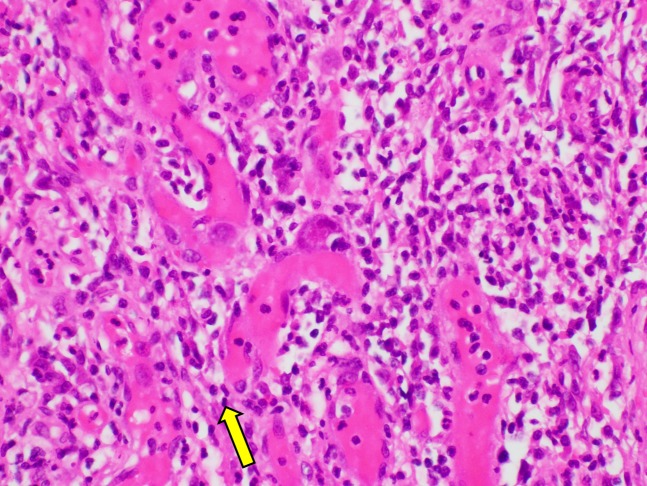

The patient underwent an urgent diagnostic laparoscopy inside an hour of presentation, revealing perforation of the terminal ileum with minimal intra-abdominal contamination (figure 2). A laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with ileocolic side-to-side stapled anastomosis was performed due to the proximity of the perforation site to the ileocaecal valve. Intravenous piperacillin–tazobactam was commenced preoperatively, as well as stress dose of intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg. His immunosuppressive therapy was restarted 24 hours following his operation. Patient care was shared between general surgery and nephrology.

Figure 2.

Urgent diagnostic laparoscopy confirmed a perforated segment in the terminal ileum approximately 20 mm distal to the ileo-caecal valve (arrow). There was minimal intra-abdominal contamination.

Due to persisting melaena, first reported 5 days postoperatively, and reduction in Hb (from 91 to 78 g/L), the patient required six units of packed red blood cells transfused cumulatively over 72 hours. He underwent a colonoscopy with successful clipping of an active bleeding site over the stapled line of the ileocolic anastomosis.

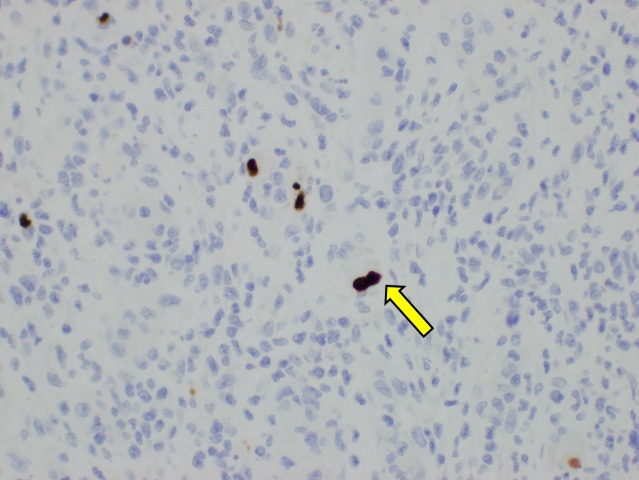

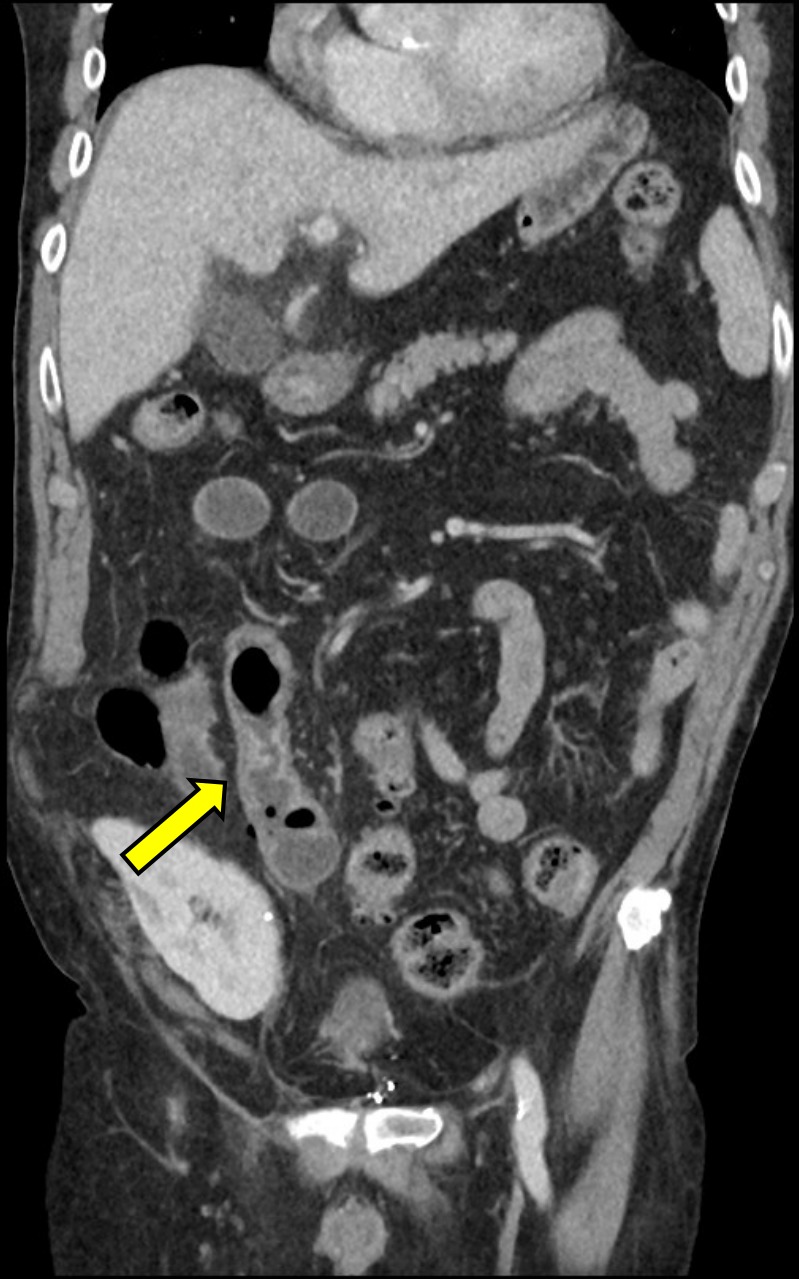

Six days postoperatively, the histopathology of the terminal ileum demonstrated a positive nuclear reaction with cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigen in the focus of inflammation and perforation (figures 3 and 4). Macroscopically, there was a sharp transition between ulcerated erythematous mucosa of the terminal ileum and unremarkable colonic mucosa. There was no dysplasia or malignancy microscopically. Quantitative assay of CMV PCR was elevated (2.43×103 IU/mL). Intravenous ganciclovir 100 mg daily was immediately commenced following the diagnosis of CMV terminal ileitis.

Figure 3.

Intranuclear large basophilic inclusion in endothelial nuclei (arrow, original magnification, ×400) were present in the terminal ileum consistent with cytomegalovirus inclusion on H&E staining.

Figure 4.

CMV-infected cells demonstrated positive brown staining (arrow, original magnification, ×100) with CMV immunohistochemistry. CMV, cytomegalovirus.

The patient acutely deteriorated 10 days postoperatively with generalised abdominal discomfort, nausea and vomiting. He was tachycardic, hypertensive and febrile. The ileocolic anastomosis appeared grossly intact with no pneumatosis or intra-abdominal collection on non-contrast CT of the abdomen/pelvis; however, there was moderate volume of free fluid extending down the pericolic gutter into the pelvis. Anastomotic leakage was excluded on a repeat diagnostic laparoscopy and intra-abdominal washout performed on the same day.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient progressively improved clinically and he was discharged 20 days following his initial diagnostic laparoscopy. He completed 21 days of full induction dose of ganciclovir before stepping down to maintenance dose.

Discussion

In postsolid organ transplant, CMV infection is very prevalent inside the first 12 months of surgery and is uncommon following this initial phase.2 4 Serological discrepancy, between the seronegative recipient and the seropositive donor, and the cessation of antiviral prophylaxis are regarded as significant risk factors in developing disseminated CMV disease. As our patient underwent renal transplant overseas, the treating team was unsuccessful in obtaining the relevant medical records stating the pretransplant serological status of the recipient and donor.

Specifically in postrenal transplant recipients, the incidence of CMV infection is highest in the first 100 days following transplant surgery according to a retrospective multicentre study.4 5 This case was an unusual manifestation of disseminated CMV disease in a postrenal transplant patient diagnosed over 10 years following the initiation of an immunosuppressive regimen. As this patient was well before presentation and his preliminary blood tests, including renal function and tacrolimus trough level, were at baseline, it is difficult to determine if any specific risk factors predisposed this patient to disseminated CMV disease. A retrospective single-centre study concluded retransplantation was the only independent risk factor of late-onset CMV disease defined as 12 months following renal transplant.6 As medical literature concerning late-onset CMV disease postrenal transplant is scarce, future studies investigating risk factors will be of significant interest.

CMV is the most common viral opportunistic infection of the following renal transplant.7 Previous studies have revealed CMV infection of the upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT) involvement is more common than lower GIT in post-transplant patients.3 Submucosal vasculitis, thrombosis and ischaemia of the affected segment result in ulceration and, very rarely, necrosis and perforation.7 8 Perforation is the most serious complication of tissue-invasive CMV disease and is associated with high operative mortality despite aggressive antiviral therapy.9 Perforation in tissue-invasive CMV disease has been reported to predominantly occur between the ileum and splenic flexure in patients with AIDS; however, this is scarcely reported in postrenal transplant patients.8 Patients may present with generalised abdominal pain, diarrhoea, unintentional weight loss and subjective fevers.3 8 In severe cases, presence of haematochezia may be suggestive of mucosal haemorrhage. Laparoscopic surgery was performed in our immunosuppressed patient, as opposed to laparotomy, to reduce the likelihood of postoperative dehiscence and incisional hernia.

Quantitative PCR testing is a valuable diagnostic method of active CMV infection by determining viral loading; furthermore, it is used in monitoring vulnerable patients classified as higher risk of CMV infection and evaluating response to antiviral therapy.10 Microscopic and macroscopic examinations of mucosal biopsy with immunohistochemical staining remain the gold standard in diagnosing tissue-invasive CMV disease. Histopathologically, infiltrative leucocytes, basophilic intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion bodies and inflammation of the lamina propria are present.8 11 12 CMV serology testing of anti-CMV immunoglobulin IgM is limited as detectable levels of anti-CMV IgM may persist between 4 and 6 months following symptom onset.2 Without previous baseline measurements, a positive anti-CMV IgM testing cannot confirm an active CMV infection. Moreover, anti-CMV IgG may not be detectable until 2–3 weeks of symptom onset.13

Intravenous ganciclovir is widely regarded as the first-line antiviral therapy in CMV disease.14 Ganciclovir is a nucleoside analogue that terminates viral DNA synthesis by selectively incorporating ganciclovir triphosphate. This therapy is 3 weeks in duration, following which patients may be treated with oral valganciclovir between 1 and 3 months if clinical symptoms have resolved. Likewise, oral valganciclovir is routinely prescribed to postrenal transplant recipients for CMV prophylaxis due to the high risk of CMV infection immediately following surgery. Intravenous foscarnet is a substitute antiviral medication when ganciclovir resistance is suspected in patients with clinical progression of CMV disease despite 3 weeks of therapy; however, this is limited in postrenal transplant due to its nephrotoxic profile.2 15

Learning points.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a very prevalent viral opportunistic infection in post-transplant patients due to their immunosuppressed state, particularly in the first 100 days of transplantation.

Disseminated CMV disease remains an important consideration in postrenal transplant patients even after many years of immunosuppressive therapy.

Tissue-invasive CMV disease is an extremely rare but morbid cause of atraumatic gastrointestinal tract perforation in postrenal transplant patients.

Histopathological analysis of the mucosal biopsy of the affected segment is the gold standard diagnostic method of tissue-invasive CMV disease. Positive features include infiltrative leucocytes, basophilic intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion bodies and inflammation of the lamina propria.

Intravenous ganciclovir is the first-line antiviral therapy for CMV disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Sooraj Pillai, MD, RCPA, for kindly providing and reporting the histopathology figures of this case.

Footnotes

Contributors: This case report was written by KK. Editing and supervision was provided by MC.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Garrido E, Carrera E, Manzano R, et al. Clinical significance of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:17–25. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azevedo LS, Pierrotti LC, Abdala E, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. Clinics 2015;70:515–23. 10.6061/clinics/2015(07)09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lempinen M, Halme L, Sarkio S, et al. Cmv findings in the gastrointestinal tract in kidney transplantation patients, patients with end-stage kidney disease and immunocompetent patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:3533–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfp408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blyth D, Lee I, Sims KD, et al. Risk factors and clinical outcomes of cytomegalovirus disease occurring more than one year post solid organ transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2012;14:149–55. 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Santos CAQ, Brennan DC, Fraser VJ, et al. Delayed-Onset cytomegalovirus disease coded during Hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2014;98:187–94. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boudreault AA, Xie H, Rakita RM, et al. Risk factors for late-onset cytomegalovirus disease in donor seropositive/recipient seronegative kidney transplant recipients who receive antiviral prophylaxis. Transpl Infect Dis 2011;13:244–9. 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00624.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yoganathan KT, Morgan AR, Yoganathan KG. Perforation of the bowel due to cytomegalovirus infection in a man with AIDS: surgery is not always necessary! BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016:bcr2015214196 10.1136/bcr-2015-214196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Michalopoulos N, Triantafillopoulou K, Beretouli E, et al. Small bowel perforation due to CMV enteritis infection in an HIV-positive patient. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:45 10.1186/1756-0500-6-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kram HB, Shoemaker WC. Intestinal perforation due to cytomegalovirus infection in patients with AIDS. Dis Colon Rectum 1990;33:1037–40. 10.1007/BF02139220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Razonable RR, Hayden RT. Clinical utility of viral load in management of cytomegalovirus infection after solid organ transplantation. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013;26:703–27. 10.1128/CMR.00015-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kotton CN, Kumar D, Caliendo AM, et al. Updated international consensus guidelines on the management of cytomegalovirus in solid-organ transplantation. Transplantation 2013;96:333–60. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829df29d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barling DR, Tucker S, Varia H, et al. Large bowel perforation secondary to CMV colitis: an unusual primary presentation of HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217221. [Epub ahead of print: 21 Dec 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Humar A, Mazzulli T, Moussa G, et al. Clinical utility of cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology testing in high-risk CMV D+/R- transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2005;5:1065–70. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Janoly-Dumenil A, Rouvet I, Bleyzac N, et al. A pharmacodynamic model of ganciclovir antiviral effect and toxicity for lymphoblastoid cells suggests a new dosing regimen to treat cytomegalovirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:3732–8. 10.1128/AAC.06423-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lumbreras C, Manuel O, Len O, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20 Suppl 7:19–26. 10.1111/1469-0691.12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]