Abstract

Atypical pulmonary carcinoid (APC) is a lung neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN), whose treatment draws from management of gastrointestinal NENs and small-cell lung carcinoma. We present a patient with recurrent metastatic APC and persistent mediastinal lymphadenopathy refractory to cisplatin and etoposide. After pursuing alternative treatments, he returned with significant progression, including diffuse subcutaneous nodules, weight loss and worsening cough. New biopsy analysis demonstrated APC with low mutational burden, low Ki-67 and Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1), and without microsatellite instability. We pursued combination nivolumab and ipilimumab treatment based on success of CheckMate 032 in small-cell lung cancer. The patient’s symptoms dramatically responded within a month, with almost complete resolution of lymphadenopathy following four cycles. He has been successfully maintained on nivolumab for the last 18 months. This suggests combination immunotherapy may be beneficial in the treatment of metastatic APC, and that PD-L1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors may be valuable in treating tumours lacking traditional biomarkers.

Keywords: cancer intervention, immunological products and vaccines, immunology, endocrine cancer

Background

Atypical pulmonary carcinoid (APC) belongs to a spectrum of disease that are collectively called lung neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) with small-cell carcinoma on the most aggressive end and typical carcinoid on the indolent side. They are considered intermediate in terms of aggressiveness, response to treatment and prognosis,1 Five-year survival rates range from 30% to 95%; 10-year survival rates 35% to 56%. Up to a quarter of patients with atypical carcinoids develop distant metastases and another quarter recur locally after resection. Local disease is typically treated with surgical resection,1 and of those, 79% required at minimum a lobectomy.2 There are no standard guidelines for adjuvant therapy even with clear risk factors such as lymph node involvement. However, adjuvant chemotherapy is routinely offered based on extrapolated data from non-small-cell and small-cell lung cancer studies.3 4 For advanced/metastatic disease, there is even less data to support generalised guidelines. Treatment regimens are based on experience from treating more common gastrointestinal NENs or the aggressive small-cell lung carcinoma. Treatment protocols include observation and octreotide or its analogues for slow growing somatostatin-receptor positive carcinoids,5 and can be used for symptomatic relief of those functional tumours resulting in carcinoid syndrome.6 For those with octreotide-refractory disease, tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as everolimus and sunitinib are utilised.7 Addition of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, everolimus, to octreotide treatment, proved to be more effective in preventing disease progression than octreotide alone in pancreatic and pulmonary NET.8 Recently, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy using the radiolabeled somatostatin analogue Lutetium Lu-177 dotatate (177Lu-dotatate) was approved by The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for tumours that are somatostatin-receptor (dotatate)-positive.9 10 Combination chemotherapy with platinum/etoposide,11 based on small-cell carcinoma experience is recommended generally for patients with aggressive, and rapidly progressive disease. It has been shown to have some efficacy in these tumours, yet is limited by nephrotoxicity in ~50% of patients.12 13 Beyond these current treatments, research for future therapeutics has focused on Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) signalling and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) binding to prevent hypervascularisation.14 Initial studies were not optimistic about the efficacy of immunotherapy in NENs, due to their lack of CD8 infiltration or Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression.14 Given the rarity of atypical carcinoids, bulk of data in literature are composed of case reports and case series. Case reports of rare tumours such APC could be extremely valuable if they provide insights into the disease process or potential treatment options.15

Here, we present the case of a young patient with recurrent APC with low PD-L1 levels and low tumour mutational burden, successfully treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy.

Case presentation

Our patient is a never-smoking 40-year-old man who was in excellent health till 2014 when he first presented to an outside institution with acute chest pain. CT scan showed left lower lobe mass as well as extensive hilar and mediastinal adenopathy. Endobronchial biopsy of a left hilar node was consistent with NENs. As per the pathology report, majority of cells had low mitotic index but a few clusters showed higher percentage of mitotic figures (5%) suggestive of atypical carcinoid. He underwent left total pneumonectomy and mediastinal staging with final pathology showing atypical carcinoid in 2 separate lung nodules as well as in 4 out of 17 lymph nodes sampled. Pathological stage was pT3N2Mx, stage IIIA as per seventh edition of American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging. Postoperative scans showed persistent enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. He completed four adjuvant cycles of cisplatin and etoposide in July 2014 but declined mediastinal radiation which was recommended by his treating physicians. Over the next year, he had repeat scans showing stable lymphadenopathy, but was then lost to follow-up for almost 3 years. In 2017, he presented to our institution with acute left chest pain, weight loss, cough and dyspnea. CT scan showed pleural thickening and significant mediastinal lymphadenopathy, concerning for recurrent disease. Further testing with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and Indium-111 octreoscan showed minimal FDG as well pentetreotide uptake respectively in areas of concern. Endobronchial biopsy of mediastinal lymph nodes showed recurrent atypical carcinoid. Mitotic figures and Ki-67 were reported as 3%, PD-L1 by immunohistochemistry was negative (<1%). Next-generation sequencing of the tumour with a 343 gene panel assay showed no genetic alterations and tumour mutational burden was reported as low (<3mut/Mb). Microsatellite status (MS) was reported as MS stable. The patient was treated with four cycles of carboplatin and etoposide with which he had stable disease on imaging studies (10% decline in target lesions by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) Guideline V.1.1) but he had marked improvement in symptoms. A 68Ga-DOTATATE scan at this time was negative for any uptake within the stable lesions (figure 1A). Approximately 6 months later, he redeveloped a persistent cough, and imaging studies showed progression of disease and a new right supraclavicular mass as well as a liver lesion. Pathology from the supraclavicular lymph node was similar to those of previous biopsies consistent with atypical carcinoid (figure 2A). PET/CT scan at this time showed no significant change in avidity (figure 1B). He was advised to start everolimus treatment, but chose to pursue 6 months of alternative treatments in another country. While we do not have access to the treatment records specifying the details of the alternative treatments, the patient stated it consisted of organic vegan diet, ozone treatment, and high doses of vitamin C and B17.

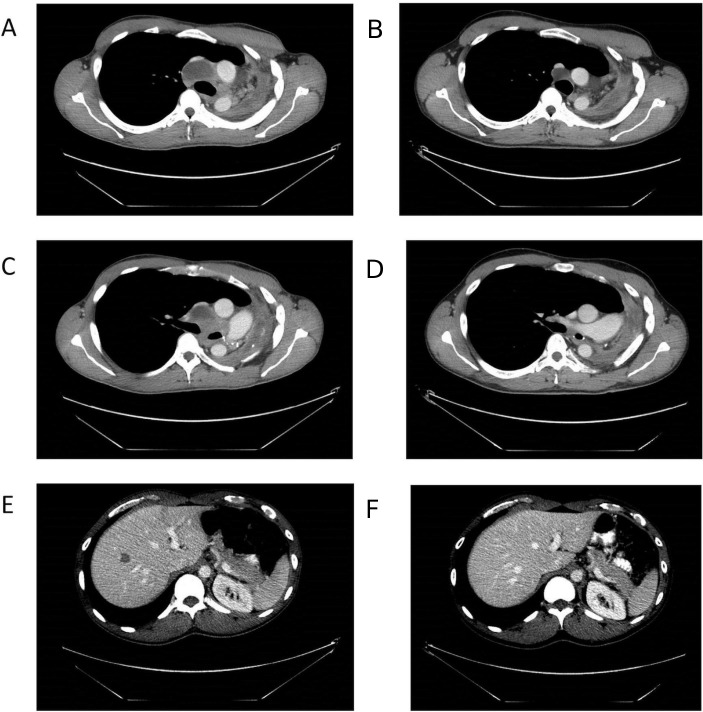

Figure 1.

PET/CT and DOTA-TATE scans. DOTA-TATE (A) and PET/CT (B) scans were performed prior to treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab. Both the DOTA-TATE scan (A) and PET/CT scan (B) were negative for uptake. PET, positron emission tomography.

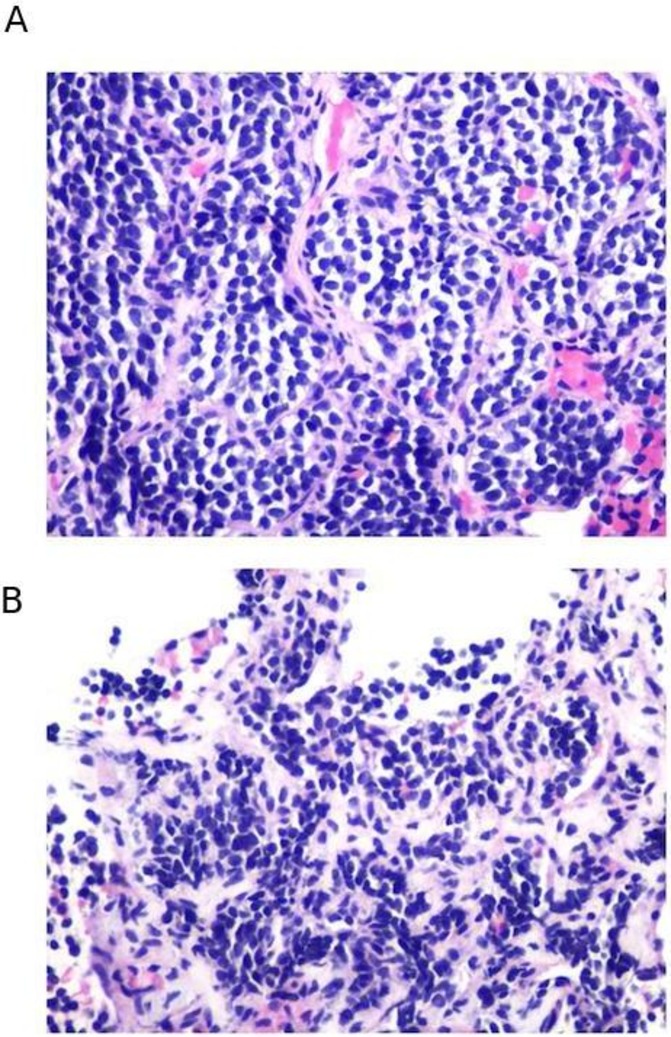

Figure 2.

Pathology of core biopsies. Analysis of core biopsies of supraclavicular lymph node (A) and abdominal subcutaneous tissue (B) were significant for metastatic neuroendocrine tumour. These biopsies were performed prior to treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab. Lymph node tissue was hypercellular with syncytial group and numerous single-lying hyperchromatic cells with coarse chromatin (A). Abdominal subcutaneous tissue was hypercellular composed of loosely cohesive groups and single-lying cells with high N/C ratio, containing finely granular chromatin pattern. No necrosis or mitoses were identified (B).

He presented again 3 months later, with significant progression of disease, including multiple new mediastinal and liver lesions (figure 3). He had also developed innumerable subcutaneous nodules, consistent with neuroendocrine cancer on biopsy (figure 2B). He also reported worsening of his cough and significant weight loss. We initiated off-label treatment of nivolumab 1 mg/kg and ipilimumab 3 mg/kg combination based on the dosing recommended by CheckMate 032 which is a phase I/II trial evaluating multiple dosing regimens of nivolumab and ipililumab in solid tumours, including advanced small-cell lung cancer.

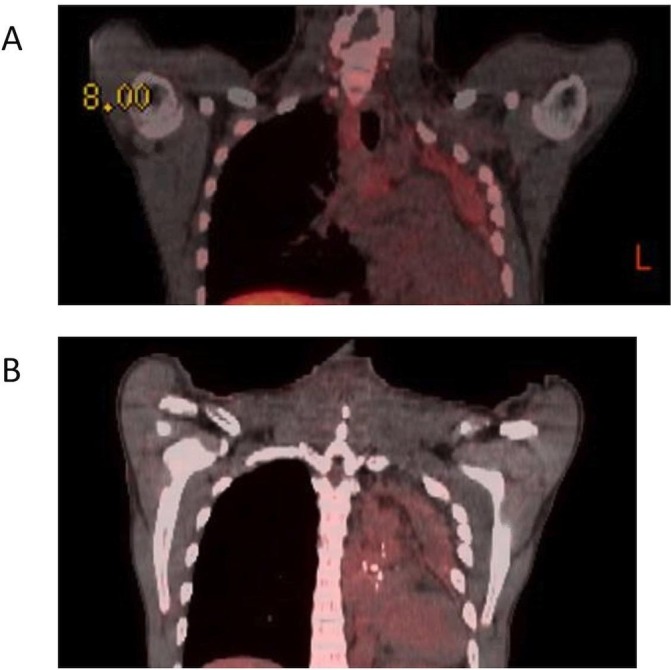

Figure 3.

CT scan imaging. After pursuing alternative treatment, the patient presented with significant progression of disease, with several mediastinal lymph nodes (A,C) and new liver lesions (E). At 2 months of treatment, imaging studies noted an excellent partial response with >80% decrease in target lesions and this response is ongoing at 18 months of treatment (B,D,F).

Outcome and follow-up

Our patient tolerated this regimen well except for grade 2 pruritic dermatitis, which was successfully managed with short course of prednisone, hydroxyzine, gabapentin and hydrocortisone cream. Within a month of starting this treatment, his cough and subcutaneous nodules completely resolved, and he started gaining weight. Repeat PET/CT after two cycles showed stable mediastinal nodes but resolution of FDG uptake. He completed four cycles, after which he was started on nivolumab maintenance therapy at 240 mg flat dose every 2 weeks thereafter. A follow-up CT of chest, abdomen and pelvis done 3 months after initiation of immunotherapy showed a near-complete response. A recent scan done at 18 months continues to show a sustained response (figure 3).

Discussion

APC, is seen in <1% of lung tumours,2 and is three times as likely to present as metastatic disease when compared with typical pulmonary carcinoid and are more likely to recur than typical carcinoids.2 4 16 As mentioned previously, there are no standard guidelines for management of advanced disease that is unresectable. Various treatment options that have been used with suboptimal efficacy include octreotide, everolimus and combination platinum/etoposide.11 This has left a void for new effective treatment options in the management of APC.

PD-1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibition has emerged as the most exciting cancer-directed strategy in the last decade.17 These checkpoint inhibitors are now being increasingly used for treating a variety of cancers including small-cell lung cancer.18 PD-L1 expression levels, tumour mutational burden and tumour microsatellite instability are the most widely used and validated factors predicting response to checkpoint inhibitors.17 19–24 Contrary to other lung cancer subtypes, both atypical and typical carcinoids generally have no or low expression of PD-L1,25 making one wonder if this is good strategy for these tumours. There have been recent trials exploring the role of these agents in NENs,26 but the efficacy data are inconsistent. Pembrolizumab as monotherapy was shown to have some activity in previously treated non-pulmonary neuroendocrine tumours,27 and PD-L1 expressing pulmonary and extrapulmonary carcinoids.28 In general, immune checkpoint inhibitors are considered to be a therapeutic option in progressive high-grade NETs with high tumour burden, microsatellite instability and/or mutational load.26 A recent study reported activity of ipilimumab and nivolumab combination in high-grade neuroendocrine cancers but not in low and intermediate grade tumours.29 To our knowledge, there have been no reports of its activity in APC, which had none of these above positive predictive factors. There are also no clinical trials that specifically target APC either. This is not surprising since APC is a rare disease with recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program database publication reporting that these tumours constitute 0.05% of all tumours involving lung and bronchus (441 out of 947 463 patients).2 16 Our patient had a sustained near-complete response to combined PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibition suggesting that like in other tumour types, combined inhibition of immune checkpoints may be an effective intervention in APC even in the absence of validated positive predictive biomarkers.

Learning points.

Atypical pulmonary carcinoid (APC) is a rare form of lung cancer that currently lacks any standardised treatment plan for unresectable disease.

PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors may serve as a beneficial intervention in the treatment of APC, as exemplified by the near-complete response in our case.

Combination immune checkpoint inhibitors may be beneficial in APC and other diseases even when tissue is lacking positive predictive biomarkers.

Footnotes

Contributors: JN and NS contributed to the writing of the manuscript. ME was responsible for pathological analysis of biopsy samples. Special thanks to KB for her contribution to clinical care.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hendifar AE, Marchevsky AM, Tuli R. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: current challenges and advances in the diagnosis and management of well-differentiated disease. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:425–36. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steuer CE, Owonikoko TK, Kim S, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of atypical carcinoid (AC) tumor of the lung: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database analysis. J Clin Oncol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. A I, Y A, T M, et al. Surgical treatment for neuroendocrine tumors other than SCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chong CR, Wirth LJ, Nishino M, et al. Chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Lung Cancer 2014;86:241–6. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Melosky B. Advanced typical and atypical carcinoid tumours of the lung: management recommendations. Curr Oncol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Granberg D, Eriksson B, Wilander E, et al. Experience in treatment of metastatic pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Ann Oncol 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramirez RA, Chauhan A, Gimenez J, et al. Management of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European neuroendocrine tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1604–20. 10.1093/annonc/mdv041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koffas A, Popat R, Mohmaduvesh M, et al. Efficacy of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in patients with advanced bronchial neuroendocrine tumours. Neuroendocrinology 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shah MH, Goldner WS, Halfdanarson TR, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors, version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fjällskog ML, Granberg DP, Welin SL, et al. Treatment with cisplatin and etoposide in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer 2001;92:1101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moertel CG, Kvols LK, O'Connell MJ, et al. Treatment of neuroendocrine carcinomas with combined etoposide and cisplatin. Evidence of major therapeutic activity in the anaplastic variants of these neoplasms. Cancer 1991;68:227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Torniai M, Scortichini L, Tronconi F, et al. Systemic treatment for lung carcinoids: from bench to bedside. Clin Transl Med 2019;8 10.1186/s40169-019-0238-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carey JC. The importance of case reports in advancing scientific knowledge of rare diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steuer CE, Behera M, Kim S, et al. Atypical carcinoid tumor of the lung: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seetharamu N, Budman DR, Sullivan KM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer: past, present and future. Future Oncology 2016;12:1151–63. 10.2217/fon.16.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cooper MR, Alrajhi AM, Durand CR. Role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in small cell lung cancer. Am J Ther 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, et al. Mechanism-Driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jacquelot N, Roberti MP, Enot DP, et al. Predictors of responses to immune checkpoint blockade in advanced melanoma. Nat Commun 2017;8 10.1038/s41467-017-00608-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2380–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science 2015;348:124–8. 10.1126/science.aaa1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee V, Murphy A, DT L, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency and response to immune checkpoint blockade. Oncologist 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsuruoka K, Horinouchi H, Goto Y, et al. Pd-L1 expression in neuroendocrine tumors of the lung. Lung Cancer 2017;108:115–20. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weber MM, Fottner C. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of patients with neuroendocrine neoplasia. Oncol Res Treat 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mulvey C, Raj NP, Chan JA, et al. Phase II study of pembrolizumab-based therapy in previously treated extrapulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas: results of part A (pembrolizumab alone). J Clin Oncol 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mehnert JM, Rugo HS, O'Neil BH, et al. 427OPembrolizumab for patients with PD-L1–positive advanced carcinoid or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: results from the KEYNOTE-028 study. Ann Oncol 2017;28 10.1093/annonc/mdx368 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patel SPP, Othus M, Chae YK, et al. A phase II basket trial of dual anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 blockade in rare tumors (dart) S1609: the neuroendocrine cohort. In: AACR Annual Meeting, 2019. Abstract CT039. [Google Scholar]