Abstract

We present an atypical presentation of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD). Due to its overlap with IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD), this case proved to be a diagnostic dilemma. Our case is an example of the importance of having a broad-based differential and, ultimately, an in-depth histopathological review. Our patient presented with a constellation of symptoms suggestive of an underlying malignancy. He was provisionally diagnosed with peritoneal carcinomatosis of an unknown primary. His initial presentation triggered a series of investigations, surgery and biopsies. Omental biopsy specimens were suggestive of IgG4-RD. Despite appropriate treatment for IgG4-RD, his disease progressed, specifically in the lungs. Pleural biopsies were then collected and assessed alongside the omental biopsies. On review and reassessment, the patient was formally diagnosed with RDD.

Keywords: rheumatology, pathology

Background

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare non-malignant histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown aetiology. Lymph nodes are the primary structure affected by this disease process. Up to 90% of cases involve painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Axillary, para-aortic, inguinal and mediastinal lymph nodes can also be affected.1 Based on data obtained from the RDD registry, approximately 43% of cases have extranodal involvement.1–3 Common extranodal sites include skin and soft tissues, upper and lower respiratory tract, bone, oral cavity and the genitourinary tract.3 Pulmonary involvement comprises just 3% of cases with extranodal disease.4 RDD involving the gastrointestinal system is exceptionally rare and occurs in less than 1% of cases.1 5 Another emerging rarity associated with RDD is that a subset of cases can mimic IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD).6 This case captures various rarities associated with RDD and represents the diagnostic dilemma it can pose for treating physicians.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man presented to the emergency department complaining of abdominal swelling, mild abdominal pain and new onset shortness of breath. His past medical history was notable for mild hypertension and type two diabetes mellitus. The man reported a 3 month history of unintentional weight loss, approximately ten pounds, and increasing night sweats. The patient appeared dyspneic with obvious abdominal swelling. He was afebrile and with a respiratory rate of 30 breaths per minute. Physical examination confirmed ascites with the presence of a fluid wave. He also had mild pitting oedema bilaterally to the mid-shin. There was no evidence of lacrimal gland swelling, jaundice, lymphadenopathy or salivary gland (parotid or submandibular) swelling. Family history was negative for any genetic conditions and malignancies. In terms of social history, the patient was a lifetime non-smoker with no history of alcohol intake. Both his hypertension and T2DM were well managed. Given the constellation of B-symptoms and ascites with no obvious cause, the patient was admitted to hospital and investigations were arranged promptly.

Investigations

An abdominal CT with contrast revealed diffuse thickening and nodularity of the mesentery with significant ascites and no significant lymphadenopathy (see figure 1). The result of the chest CT was unremarkable. Based on imaging, the initial provisional diagnosis was extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis of an unknown primary. Paracentesis was performed and 6L of cloudy yellow fluid was drained. Fluid analysis revealed a largely inflammatory component, with approximately 94% neutrophils. No malignant cells were identified on cytology; acid fast bacilli stains were negative.

Figure 1.

CT f the abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast, evidence of omental caking: the arrows highlight diffuse thickening and nodularity of the mesentery (image courtesy of Dr Mollie Carruthers and Dr Navi Shergill).

Endoscopy and colonoscopy were performed with the intention of locating the primary malignancy. Both of these investigations, however, revealed no significant findings. Due to the lack of conclusive findings, percutaneous ultrasound-guided biopsy of the peritoneum was attempted. The biopsy revealed heavily inflamed fibre-adipose tissue with areas of mesothelial hyperplasia. Despite these investigations, the diagnosis remained inconclusive; the decision to proceed with an exploratory laparotomy was made.

The goal for exploratory laparotomy was removal of the omentum. Intraoperatively, the omentum was found to be unresectable; instead, multiple biopsies of the omentum and surrounding tissues were collected.

The surgical biopsy specimens were all noted to be morphologically similar. There were giant cells, chronic inflammatory cells and numerous plasma cells suggestive of an inflammatory process. There was also extensive fibrosis with hyalinisation. There was no evidence of malignancy and granulomas, and stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungi and Gram stains were negative. IgG4 staining revealed moderate to high plasma cells, as many as 80 cells per high power field. The ratio of IgG4/IgG-positive cells was as high as 50%. A diagnosis of IgG4-related sclerosing mesenteritis with associated ascites was made.

Additional investigations revealed the following: the white cell count was normal at 9.0 G/L (4–10), haemoglobin decreased at 124 g/L (135–170) and platelets increased at 402×109/L (150–400). The total protein was low at 56 g/L (62–82) and the albumin at 21 g/L (34–50), but the other liver function tests were normal, including alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase. The IgG4 level was slightly elevated at 1.33 g/L (0.052–1.250) and the C reactive protein was 34.6 mg/L (>10).

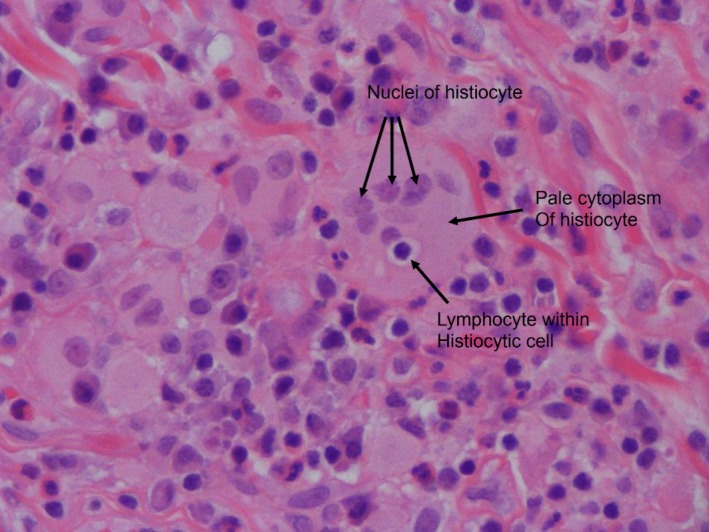

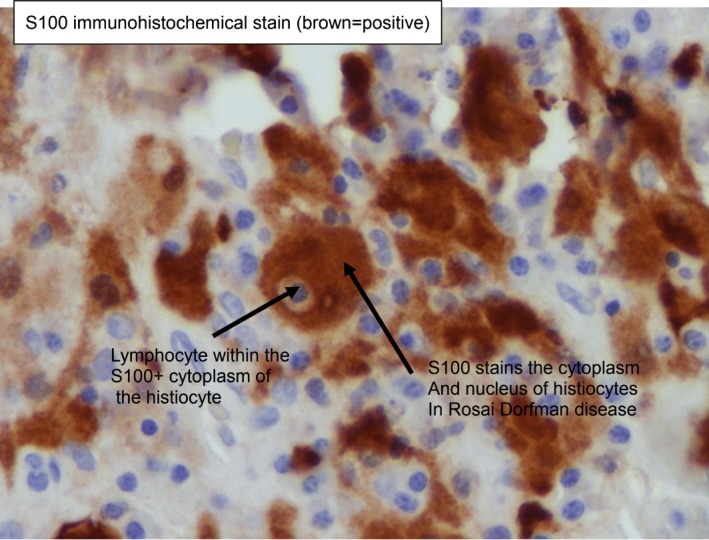

A course of two infusions of rituximab 1000 mg intravenous that were 15 days apart was initiated for presumed IgG4-RD. The patient’s symptoms initially improved and he experienced a resolution of his ascites confirmed by physical examination and imaging. However, 3 months into his second rituximab course, the patient developed bilateral pleural effusions and his ascites returned. The initial diagnosis was questioned based on his worsening despite treatment. A right-sided pleural biopsy was obtained by video-assisted thoracoscopy. The pleural biopsy demonstrated a dense histiocytic and plasmacytic infiltrate within the pleura. The histiocytes demonstrated abundant pale cytoplasm, which was not foamy. Emperipolesis, the presence of intact lymphocytes and/or plasma cells within histiocytes, was noted (figures 2 and 3). There were multiple multinucleated giant cells with no obvious granuloma formation identified. Immunohistochemistry showed the histiocytes to be strongly positive for s100 and CD68, a pattern noted in RDD.1 CD1a, a marker seen in Langerhans cell histiocytosis, was negative. There was a high IgG4 concentration with a ratio of IgG4/IgG over 40% and more than 40 IgG4 plasma cells per high-power field. Other findings of IgG4, such as obliterative phlebitis and storiform fibrosis, were not identified. CD117, seen in malignancies such as gastrointestinal stromal tumours, was negative.

Figure 2.

Emperipolesis: intact lymphocyte within the cytoplasm of a histiocyte (image courtesy of Dr Brian Skinnider, University of British Columbia).

Figure 3.

S100 staining, a marker for Rosai-Dorfman disease, is positive. (Image courtesy of Dr Brian Skinnider, University of British Columbia)

A review of the previous omental biopsies revealed a similar histiocytic and plasmacytic cell population. However, the initial biopsies showed a more extensive fibrosis, and this obscured the pathognomonic inflammatory infiltrate. The diagnosis of RDD was made.

Differential diagnosis

The differential for an infiltrative process in the mesentery and pleura is broad based. It includes sarcoidosis, lymphoma, IgG4-RD, amyloidosis, histiocytosis and carcinomatosis. This patient’s initial presentation was concerning for an underlying malignancy. The result of the CT of the abdomen with contrast was highly suggestive of extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, with a possible colonic primary. Other differential diagnoses that were considered included tuberculosis peritonitis and lymphoma.

Treatment

Corticosteroids can be used in the first-line treatment of RDD.7 Other steroid sparing agents may be used. This patient was given tocilizumab as off- label therapy.8 The patient was not treated with corticosteroids as per patient preference.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient has remained in remission for the past 2 years since the initiation of this off-label treatment. He has resumed his usual activities of daily living and has not been hospitalised since.

Discussion

IgG4-related disease

IgG4-RD is an increasingly recognised immune-mediated fibroinflammatory condition with multiple manifestations previously thought to be different and unrelated. The disease is characterised by tumour-like swelling in affected organs in which lesions demonstrate dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates rich in IgG4+ plasma cells, as well as fibrosis, usually in a characteristic storiform pattern and often with an associated elevation in serum IgG4 concentration.9 10 Typical organ systems include the pancreas, salivary glands, orbits, lung, kidney and aorta.10

The unique characteristic features of IgG4-RD are a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, storiform-type fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis.9 There are various mimickers of IgG4-RD and they are listed in table 1. Many of these conditions are associated with increased numbers of IgG4-positive cells in tissue but should not share features of storiform fibrosis, obliterative fibrosis and tissue eosinophilia. Various inflammatory conditions, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and RDD, may be associated with increased numbers of IgG4-positive cells.9 Lymphomas, such as extranodal marginal zone lymphomas, and occasionally follicular lymphomas and angioimmunoblastic lymphomas can appear similar histologically.9 Infiltration with IgG4 plasma cells has been described in solid tumours, particularly in pancreatobiliary cancers.9 Hence, it is important to note that the presence of IgG4 plasma cells in isolation is not diagnostic for IgG4-RD. The potential diagnostic ambiguity in the histopathological diagnosis of IgG4-RD is central to the illustrative case. We suggest that the initial diagnosis of IgG4-RD was incorrect.

Table 1.

Various mimickers of IgG4-RD associated with increased numbers of IgG4-positive cells (from Deshpande et al’s consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-RD9

| Inflammatory | Malignant |

|

|

IgG4-RD, IgG4-related disease.

Rosai-Dorfman disease

RDD, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, was first described in 1969 by Rosai and Dorfman.1 It is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown aetiology. Current evidence suggests immune dysfunction and viral infections; in particular, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpes virus may contribute to the pathogenesis of this disease.1–3 RDD involves non-malignant histiocytes infiltrating lymph nodes or extranodal tissues. The common presentation involves the triad of fever, leukocytosis and non-painful bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy. Case series studies have demonstrated extranodal involvement of 40%.11 Extranodal sites involved that have been described include the skin, central nervous system, orbit, upper respiratory tract and gastrointestinal tract.7 Up to 90% of patients have elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinaemia.7 According to a registry of RDD cases, pulmonary and gastrointestinal involvement is rare.2 Pulmonary RDD is most common among women during their teen to middle age years.12 Involvement of the lower respiratory tract is most often associated with poor prognosis, in which one-third of patients die from the disease, and more than one-third have a progressive course of the disease.13

The diagnosis of RDD is made through a constellation of immunohistochemical features. Histologically, affected tissue shows infiltration by histiocytes with intact lymphocytes within an abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm. This phenomenon of intact cells within another cell is known as emperipolesis or lymphocytophagocytosis.1 Immunohistochemical stains are useful in sorting out morphologically ambiguous cases, and RDD histiocytes are positive for S100, CD68 (KP-1) and CD163.7

Recent evidence suggests there may be a degree of overlap between extranodal RDD and IgG4-RD.14 It should be noted that there is no evidence to suggest the two disease processes share the same pathogenesis.14 Currently, there is no uniform approach for investigating RDD.14 Treatment is best tailored to the individual case and circumstances.14 Nodal RDD is considered to be a benign, self-limiting condition that undergoes spontaneous remission in up to 50% of cases.14 In contrast, the outcome of extranodal RDD is variable. Surgical excision was initially considered to be the treatment of choice for those with extranodal disease.15 However, there are a wide range of medical treatments that have proven effective in the management of extranodal RDD; these include steroids, chemotherapeutic agents, tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors and BRAF inhibitors.14

Patient’s perspective.

My illness started with a number of unusual symptoms. There were fevers and night sweats. I was losing weight. At first, I did not give these symptoms much thought. I continued to work and be productive on a daily basis. Then my waist began to appear larger and I attributed this to my diet. Ultimately, I found myself unable to catch my breath.

I went to the local emergency department and I was told I had a buildup of fluid in my abdomen. They then did a CT scan, which showed possible cancer that had spread throughout my abdominal cavity, and the doctors informed me and my family that I had a very short time to live. My CT scan triggered a long back and forth process of hospitalisations and tests in the coming weeks. I was focused on getting answers from my doctors, friends, family and the internet. I tried not to think about the possibility that this was a terminal cancer and more on how to move forward towards a solution. When I was first discharged, my treating team had organised a series of outpatient appointments and tests for me, with the aim of finding where the cancer began. However, I soon found myself readmitted to the hospital, this time with a fever and vomiting. I was told I had an infection. At this time, the doctors drained approximately 6 L of fluid from my belly. They also attempted a needle biopsy and also ultrasound, but the doctor was not convinced and decided that they would need to do an exploratory surgery to find the tumour. They told me that it was not whether I had cancer or not but they were only trying to find where it was. At the end of the surgery, I was informed that they did not find any cancer, and instead, the surgeons had collected multiple tissue samples for further testing. They did not have the results yet.

During my 2 weeks at the hospital, the extensive amount of testing and surgery by the oncology team, I was passed onto the infectious diseases team, which put me in full isolation for tuberculosis, and after another week of testing, they found nothing and I was discharged. Just the day I was discharged, I was told that I had a very rare disease called IgG4, which was unknown to most doctors, and there was nobody who would be able to treat me for this. Two days after being discharged, I received a call from the hospital that there was a very bright young doctor who had moved to Vancouver and was willing to take me as a patient. Dr Mollie Carruthers was God sent and I am forever grateful for what she has done for me and many other friends and family that I have referred to her.

I started an infusion therapy under the direction of my rheumatologist. At first, I felt great. Then, a few months after my second infusion treatment, I developed fluid, but this time around in my lungs. I found myself breathless again, and I was readmitted to the hospital. I had to have fluid around my lungs drained on a weekly basis where I was accumulating 2 L a week. Ultimately, it seemed I should have been doing better on the infusions. My rheumatologist asked for more tissue samples to be tested. Afterwards, my rheumatologist reviewed my lung and abdominal biopsies. In yet another twist, I was told that I did not have IgG4-related disease but, instead, another rarer disease called Rosai-Dorfman. My medication was changed and here I am, over 2 years since this entire ordeal started, and I have thankfully been out of hospital. No more fluid in my lungs or belly, and no more hospital admissions. Due to the care I have received from my doctor and my current medication, I have been able to do the things I love, spend time with my family, continue working and remain actively involved with my faith.

Learning points.

Given the complexity of the presentations of immune-mediated diseases such as IgG4-related disease and Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), careful histopathological assessment by an experienced pathologist should be initiated in these cases to make a definitive diagnosis.

This case highlights the importance of having a broad-based differential. RDD is not encountered often, but it often mimics other pathologies, including malignancies.

Nodal RDD, in some cases, can be managed with observation and regular follow-up, as most cases can undergo spontaneous regression.

Extranodal RDD has a variable prognosis and course.

Currently, there are no set standards of care/guidelines for the treatment of RDD. A range of treatment options exist, including systemic corticosteroids, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgical excision, tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors and BRAF inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Dr Navi Shergill, interventional radiologist, for providing his expertise and guidance with the CT abdomen images.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors provided substantial intellectual contribution and participation in the generation of this case report. ND, was responsible for the the acquisition/collection of all information and the chronological assessment of all information; she wrote the original draft, made the revisions decided upon by the group and finalised all edits. SD also contributed substantially to the write-up, research and references involved in this article generation. MC was the physician in charge of taking care of the patient. She provided guidance on the timeline for the patient’s case, along with improvements to the original draft and editing of the multiple draft versions that were created by ND and SD. MC helped research the case and contributed to the discussion and writing of the case. Ultimately, she signed off on the case report when she felt it was ready to be submitted for consideration to the BMJ Case Reports. Her expertise in the recognition and treatment of Rosai-Dorfman disease were pivotal in navigating the approach to this case report, finding resources and helping develop a succintly written case report. BS was instrumental in getting the final diagnosis correct. He provided thorough histopathological analysis and interpretation of the histopathological specimens, and ultimately helped guide the treating team to the correct diagnosis.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol 1990;7:19–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaitonde S, Multifocal GS. Multifocal, extranodal sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007;131:1117–21. 10.1043/1543-2165(2007)131[1117:MESHWM]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rajasekharan C, Ratheesh NS, Nandinidevi R, et al. Rosai Dorfman disease: appearances can be deceptive. Case Reports 2012;2012 10.1136/bcr-2012-006723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. El-Kersh K, Perez RL, Guardiola J. Pulmonary IgG4+ Rosai-Dorfman disease case reports 2013, 2013. Available: https://casereports.bmj.com/content/casereports/2013/bcr-2012-008324.full.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Zhao M, Li C, Zheng J, et al. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease involving appendix and mesenteric nodes with a protracted course: report of a rare case lacking relationship to IgG4-related disease and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013;6:2569–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mahajan VS, Mattoo H, Deshpande V, et al. Igg4-Related disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2014;9:315–47. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control 2014;21:322–7. 10.1177/107327481402100408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wade SD, Seidman MA, Jones EC, et al. Anti-Interleukin-6 therapy for Erdheim-Chester disease warrants study. The Rheumatologist 2017;11:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1181–92. 10.1038/modpathol.2012.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. Igg4-Related disease. N Engl J Med 2012;366:539–51. 10.1056/NEJMra1104650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg 2006;10:281–90. 10.2310/7750.2006.00067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roberts SS, Attanoos RL. IgG4+ Rosai-Dorfman disease of the lung. Histopathology 2010;56:662–4. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zander DS, Farver CF. Pulmonary pathology E-Book: a volume in the series: foundations in diagnostic pathology. Elsevier health sciences 2016.

- 14. Abla O, Jacobsen E, Picarsic J, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and clinical management of Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. Blood 2018;131:2877–90. 10.1182/blood-2018-03-839753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heidarian A, Anwar A, Haseeb MA, et al. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease arising in the heart: clinical course and review of literature. Cardiovasc Pathol 2017;31:1–4. 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]