Abstract

Sirenomelia, also known as mermaid syndrome, is an extremely rare congenital disorder involving the lower spine and lower limbs. We present a case of a grand multiparous with poorly controlled gestational diabetes who delivered a live baby weighing 2.43 kg at 38 weeks’ gestation. The baby was noted to have significant respiratory distress, and resuscitation was promptly commenced. Severe congenital abnormalities indicative of sirenomelia were obvious and after availability of antenatal records which indicated an extremely poor prognosis, resuscitative efforts were aborted. The baby was handed over to the mother for comfort care and died 18 min postdelivery.

Keywords: neonatal and paediatric intensive care, neonatal health, materno-fetal medicine, congenital disorders, genetic screening / counselling

Background

Sirenomelia is an extremely rare and lethal multisystemic congenital condition. The definite aetiology continues to remain undetermined.1 It has an incidence of 1 in 100 000 births along with a male predominance.1 Although usually fatal in the newborn period, survival beyond infancy has been reported in a handful of cases. Diagnosis can be proposed in the first trimester of pregnancy, and although the second trimester scan offers a more definite picture, malformations are visualised with difficulty due to deficiency of amniotic fluid (ie, oligohydramnios).2 Most babies with sirenomelia die within the first few minutes/hours of life indicating the extremely poor prognosis due to multiple anomalies often incompatible with life. Although numerous risk factors have been associated with sirenomelia and several theories regarding pathogenesis have been proposed, the definitive aetiology and pathogenesis continues to remain poorly understood, indicating the need for more research in this area.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old Gravida 17, Para 16, Romanian woman with known gestational diabetes mellitus, poorly controlled on insulin, delivered a live baby at 38 weeks’ gestation in an ambulance en route to the hospital. This baby was the 17th child born to non-consanguineous parents. On arrival, the mother and the baby were transferred directly to the labour ward. With a birth weight of 2.43 kg, the baby was noted to be cyanosed and in respiratory distress. Paramedics provided bag and mask ventilation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. On inspection, severe congenital abnormalities were noted. Facial dysmorphism included flattened facies, ocular hypertelorism, upward slanting palpebral fissures, broad and depressed nasal bridge, posteriorly located, low-set malformed ears and receding chin (figures 1–2). Other apparent dysmorphology included a short neck, small thoracic cage, ambiguous genitalia, absent anal opening and fused lower limbs (figures 3–4). Of note, the feet were not completely fused (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Anterior view of the patient with evident flattening of facial features.

Figure 2.

Lateral view of the patient demonstrating upslanting palpebral fissure, low-set malformed ears, depressed nasal bridge and receding chin.

Figure 3.

Anterior view of the patient showing fused lower limbs and ambiguous genitalia. Of note, the feet are separate (sirenomelia dipus).

Figure 4.

Posterior view of the patient showing absent anal opening and fusion of the lower limbs.

The mother was originally booked for delivery at a tertiary referral centre where she had undergone antenatal scanning. The fetal anatomy scan carried out at 22 weeks had reported oligohydramnios (the prime cause of fetal pulmonary hypoplasia), absent left kidney, right cystic dysplastic kidney and cardiac malformations which could not be accurately identified at the time (due to oligohydramnios). She had received counselling for the anticipated poor prognosis of her baby due to the multiple abnormalities noted on her scans. Her prior obstetric history included the birth of a boy (now age 4) with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).

The mother was brought in by ambulance into the hospital due to its geographic proximity given the urgency of this case. Furthermore, the fact that the mother’s antenatal care was not provided by the hospital meant that we were unaware of her case and the pre-established management plan. The baby was subsequently intubated and positive pressure ventilation was promptly commenced. Shortly afterwards, the futility of resuscitation became obvious. After establishing communication with the doctors providing antenatal obstetric services to the mother, we received more information regarding the baby’s predetermined poor prognosis. The baby was extubated at 18 min of life and was handed over to the mother for comfort care.

Investigations

Postdemise, bloods obtained from the baby was sent for genetic testing. Microarray results were normal, and karyotyping revealed that the baby was female. Additionally, CT skeletal survey was performed and revealed malformed pelvis and vertebrae along with soft tissue fusion of both lower limbs (figures 5 and 6).

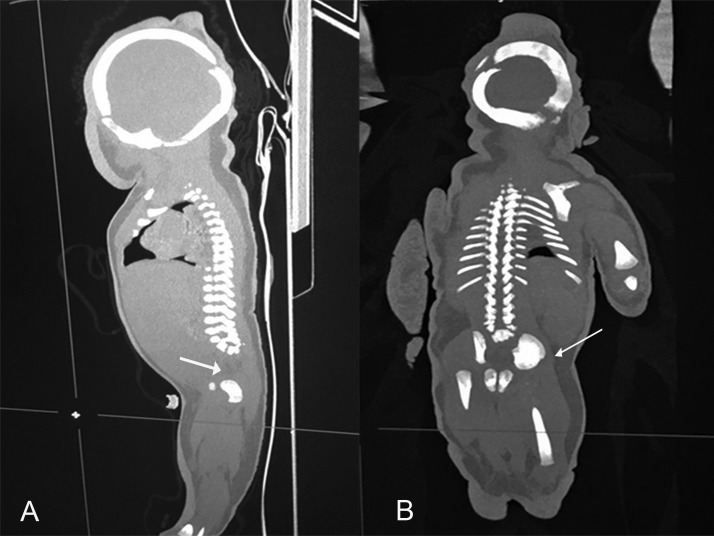

Figure 5.

CT skeletal survey. (A) Sagittal section showing absent sacrum. (B) Coronal section showing small malformed pelvic bones.

Figure 6.

CT skeletal survey. Coronal section showing lower limbs soft tissue attachment extending down to the distal lower limbs with sparing of the feet. Of note, bony fusion of the left and right femur and tibia is not seen.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included three multisystemic congenital syndromes including sirenomelia, Potter’s syndrome and caudal regression syndrome. However, due to the presence of the defining characteristic dysmorphology (ie, fused lower limbs), the diagnosis of sirenomelia was clear.

Outcome and follow-up

The baby passed away 18 min after being delivered. Permission for autopsy was declined by the parents.

Discussion

Sirenomelia is an extremely rare and lethal multisystemic congenital malformation with an estimated incidence of 1 in 100 000 births.1 It is broadly classified based on the number of lower limb bones present. Sirenomelia apus is when there is absence of both feet, sirenomelia unipus implies the presence of one foot only and sirenomelia dipus is described by presence of both feet and consequent best outcome.1 Prognosis, however, depends on the presence and severity of other abnormalities especially impaired renal function.1 This case was that of sirenomelia dipus.

The most common anomalies present with sirenomelia sequence include renal agenesis, anorectal and genital anomalies, single umbilical artery and low spinal column defects.2 The baby in this case had absent anal opening and ambiguous genitalia alongside fused lower limbs. Moreover, oligohydramnios due to renal agenesis explains the characteristic Potter’s facies.

While maternal diabetes has been linked with caudal regression, its association with sirenomelia is unclear.2–4 There have been a few reported sirenomelia cases to non-diabetic mothers, indicating that no definite cause can be attributed to these cases.5 Sirenomelia’s correlation to maternal age younger than 20 and older than 40 years has also been noted implying that extremities in age may be an important risk factor.6 7

Although an exact aetiology has not been identified, several hypotheses regarding pathophysiology have been proposed. One such hypothesis is the ‘Vascular steal theory’. This theory proposes that agenesis of caudal structures occurs due to impaired blood supply to the caudal mesoderm.8 9 Another hypothesis is the ‘Theory of defective blastogenesis’, which describes that incomplete development of the caudal region and malformed lower limbs is a result of ischaemia due to defective angiogenesis.10

This case report aims to identify and report a rare congenital disorder. Research on sirenomelia has not found any conclusive risk factors that contribute to the development of this condition. Maternal age and gestational diabetes are likely risk factors, but further research is required to establish these associations.

Learning points.

Sirenomelia remains a lethal condition with multisystemic involvement which makes this condition incompatible with life in the majority of the cases.

Although a few surviving cases have been reported, these babies have had poor outcomes due to multiple comorbidities.

Research in this area is lacking due to isolated cases occurring every year worldwide. More research is needed to obtain a better understanding of the aetiology and pathophysiology in order to prevent future cases and/or develop antenatal/postnatal treatments to improve outcomes.

Footnotes

MIR and BK contributed equally.

Contributors: MIR is the main contributor in this case report. He is responsible for taking consent from the mother, briefing the mother about the patient’s condition and to use information for publication and study purpose. BK contributed by providing the research references for the discussion piece, after discussing with MIR and FS. FS supervised and proofread the case report. JA was the consultant present at the time of incidence and was responsible for suggesting that this case be reported.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Reddy KR, Srinivas S, Kumar S, et al. Sirenomelia: a rare presentation. J Neonatal Surg 2012;1:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al-Haggar M, Yahia S, Abdel-Hadi D, et al. Sirenomelia (symelia apus) with Potter's syndrome in connection with gestational diabetes mellitus: a case report and literature review. Afr Health Sci 2010;10:395–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan BWH, Chan K-S, Koide T, et al. Maternal diabetes increases the risk of caudal regression caused by retinoic acid. Diabetes 2002;51:2811–6. 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davari Tanha F, Googol N, Kaveh M. Sirenomelia (mermaid syndrome) in an infant of a diabetic mother. Acta Med Iran 2003;41:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saxena R, Puri A. Sirenomelia or mermaid syndrome. Indian J Med Res 2015;141:495 10.4103/0971-5916.159323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taee N, Tarhani F, Goodarzi MF, et al. Mermaid syndrome: a case report of a rare congenital anomaly in full-term neonate with thumb deformity. AJP Rep 2018;8:e328–31. 10.1055/s-0038-1669943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Källén B, Castilla EE, Lancaster PA, et al. The cyclops and the mermaid: an epidemiological study of two types of rare malformation. J Med Genet 1992;29:30–5. 10.1136/jmg.29.1.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garrido-Allepuz C, Haro E, González-Lamuño D, et al. A clinical and experimental overview of sirenomelia: insight into the mechanisms of congenital limb malformations. Dis Model Mech 2011;4:289–99. 10.1242/dmm.007732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stevenson RE, Jones KL, Phelan MC, et al. Vascular steal: the pathogenetic mechanism producing sirenomelia and associated defects of the viscera and soft tissues. Pediatrics 1986;78:451–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Opitz JM, Zanni G, Reynolds JF, et al. Defects of blastogenesis. Am J Med Genet 2002;115:269–86. 10.1002/ajmg.10983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]