Abstract

Background

Todani type 1 and 4 choledochal cysts are associated with a risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma. Resection is usually recommended, but data for asymptomatic Western adults are sparse. The aim of this study was to investigate diagnostic interpretation and attitudes towards resection of bile ducts for choledochal cysts in this subgroup of patients across northern European centres.

Methods

Thirty hepatopancreatobiliary centres were provided with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatograms and asked to discuss the management of six cases: asymptomatic non‐Asian women, aged 30 or 60 years, with variable common bile duct (CBD) dilatations and different risk factors in the setting of a multidisciplinary team (MDT). The Fleiss κ value was calculated to estimate overall inter‐rater agreement.

Results

For all case scenarios combined, 83·3 and 86·7 per cent recommended resection for a CBD of 20 and 26 mm respectively, compared with 19·4 per cent for a CBD of 13 mm (P < 0·001). For patients aged 30 and 60 years, resection was recommended in 68·5 and 57·8 per cent respectively (P = 0·010). There was a trend towards recommending resection in the presence of a common channel, most pronounced in the 60‐year‐old patient. High amylase levels in the CBD aspirate led to recommendations to resect, but only for the 13‐mm CBD dilatation. There were no differences related to centre size or region. MDT discussion was associated with recommendations to resect. Inter‐rater agreement was 73·3 per cent (κ = 0·43, 95 per cent c.i. 0·38 to 0·48).

Conclusion

The inter‐rater agreement to resect was intermediate, and the recommendation was dependent mainly on the diameter of the CBD dilatation.

Resection of Todani type 1 and 4 choledochal cysts is recommended because of a reported long‐term risk of malignancy. Data for asymptomatic non‐Asian adults are sparse. This study found differences between the radiological definition and surgeons' interpretation among northern European hepatopancreatobiliary centres; there was intermediate agreement to resect.

Common bile duct dilatation determines the treatment.

Antecedentes

Los quistes de colédoco (choledochal cysts, CC) tipo 1 y tipo 4 de Todani se asocian con un riesgo de desarrollar colangiocarcinoma. Generalmente se recomienda la resección de los mismos, pero los datos para pacientes adultos occidentales son escasos. El objetivo del presente estudio fue investigar la interpretación diagnóstica y actitudes respecto a la resección de las vías biliares por CC en este subgrupo de pacientes atendidos en centros del norte de Europa.

Métodos

Se proporcionaron imágenes de colangiopancreatografía por resonancia magnética (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, MRCP) a un total de 30 centros especializados en patología hepatobiliar y se les solicitó que discutieran el tratamiento de seis casos: pacientes del sexo femenino no asiáticas asintomáticas, de edad entre 30 y 60 años con dilataciones variables del colédoco (common bile duct, CBD) y con diferentes factores de riesgo en el marco de un equipo multidisciplinario (multidisciplinary team, MDT). Se calculó el índice kappa de Fleiss para estimar el acuerdo global entre los evaluadores.

Resultados

Para todos los escenarios de casos combinados, un 83,3% y un 86,7% recomendaron la resección para un CBD de 20 y 26 mm, respectivamente, en comparación con un 19,4% para un CBD de 13 mm (P < 0,001). En el caso de un paciente de 30 y de 60 años, la resección se recomendó en el 68,5% y 57,8%, respectivamente (P = 0,010). Se observaron tendencias hacia recomendar la resección en presencia de un canal pancreático‐biliar común, más pronunciado en el paciente de 60 años. Los niveles elevados de amilasa en el aspirado del CBD condujeron a la recomendación de resecar, pero solo en la dilatación del CBD de 13 mm. No hubo diferencias relacionadas con el tamaño del centro o la región. La discusión en el MDT se asoció con recomendaciones para la resección. El acuerdo entre evaluadores fue 73,3% con un índice kappa de 0,43 (i.c. del 95% 0,38‐0,48).

Conclusión

El acuerdo entre evaluadores para indicar la resección fue intermedio y la recomendación dependió principalmente del diámetro de la dilatación del CBD.

Introduction

Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic transformations of the extrahepatic and/or intrahepatic biliary tree. They are a rare entity in the Western population, although increasingly diagnosed in adults1. Choledochal cysts have a female : male predominance of 4 : 1, and are notably more common in the Asian population2, 3. Most choledochal cysts are diagnosed in children aged less than 10 years, with only 20 per cent being diagnosed after the age of 20 years. Although the majority of cases in adults are diagnosed incidentally, these patients may have various symptoms, including right upper quadrant pain and jaundice4, 5.

The exact aetiology of a choledochal cyst is essentially unknown. It has been suggested6, 7 that reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the biliary tree through an anomalous pancreatobiliary duct union (APBDU) exposes the biliary epithelium to pancreatic enzymes, contributing to cyst formation. The APBDU implies a junction of the common bile duct (CBD) and the pancreatic duct occurring outside the duodenal wall, allowing reflux of pancreatic fluid into the biliary tree6, 8. This ‘long common channel’ is defined as insertion of the CBD more than 15 mm from the ampulla of Vater. Long common channels are seen most commonly in paediatric patients with choledochal cysts, again indicating that the anomaly is also associated with symptoms leading to an early diagnosis. Amylase levels in the bile are typically raised in patients with an APBDU. A recent French study suggested a cut‐off value for intrabiliary amylase of 8000 units/l to be indicative of amylase reflux8, 9. As an APBDU has been reported to be present in only 50–90 per cent of all patients with choledochal cysts8, 10, 11, there must be other mechanisms behind cyst formation that remain unknown.

Choledochal malformations are classified according to the system of Todani and colleagues12. Some subtypes (1 and 4) are associated with the development of cholangiocarcinoma13. The risk of malignant transformation increases with age, with a cancer incidence rising from 0·7 per cent in the first decade of life to a lifetime risk of more than 14 per cent after the age of 20 years3, 14, 15. The risk of cancer development in choledochal cysts has led to the recommendation to excise the entire extrahepatic biliary tree followed by hepaticoenterostomy2, 3, 16, 17. Although recommendations to resect Todani type 1 and 4 cysts are well established18, they appear primarily to address clearcut cases and do not allow for any borderline interpretation of the more subtle variants. Furthermore, choledochal cysts are rare in non‐Asian populations, so knowledge regarding optimal management and long‐term outcomes in a Western population is limited.

It was hypothesized that incidental findings of subtle dilatations of the CBD might be interpreted differently across northern European centres, and hence that attitudes towards resection might vary. The objective of the present study was to assess the attitudes of hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) surgeons in northern Europe with respect to definitions of choledochal cysts and the inclination to resect in asymptomatic non‐Asian adults.

Methods

Case scenarios

Three real‐life scenarios (cases A, B and C) were selected from referrals for choledochal cyst evaluation to centres in Oslo (Norway) and Edinburgh (UK). A representative single image was extracted from each of their magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) series, showing a fusiform dilated extrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 1). All three patients were women, non‐Asian and asymptomatic, and the finding of a dilated CBD was incidental. To facilitate analysis, two versions of each case were presented: one with the patient age set at 30 years, and the other at 60 years.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatograms in the coronal oblique plane showing fusiform dilatation of the bile duct, referred as a choledochal cyst The diameter of the dilated portion of the common bile duct (CBD) was a 13 mm, b 20 mm and c 26 mm. All three cases were sent to the 30 participating centres.

Respondents were asked whether they interpreted the images as a Todani type 1 cyst, a cyst of another subtype, or just a physiological dilatation (no choledochal cyst). Respondents were asked whether they would recommend resection if the patient was 30 or 60 years old, provided there were no signs of a long common channel (APBDU) and no aspiration of bile was performed. Answers were binary as yes or no. The questions regarding resection were repeated with the additional assumption of a common channel longer than 10 mm, and lastly assuming that aspirated bile showed an amylase content of more than 8000 units/l. For stratification purposes, centres were asked for their mean annual HPB surgery volume and whether the patients were discussed in a multidisciplinary team (MDT) setting. A cut‐off at 200 resections (liver, pancreas and biliary) per year was used to differentiate high‐ from low‐volume centres. The survey was distributed by e‐mail to a contact surgeon at each site, and the completed survey forms were returned by e‐mail.

Participating sites and data collection

All major centres performing HPB surgery in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands, and six selected centres in the UK, were invited by e‐mail to participate in the survey.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as incidences and percentages of the replies. Each CBD diameter and patient age was considered an independent case (six in total). Categorical data were compared with Pearson's χ2 test, or Fisher's exact test if the expected cell count number of any cell was less than five. Risk factors (none, common channel or bile duct aspirate) were considered different scenarios of any of the six cases, and analysed as paired categorical data in cross‐table analysis with the McNemar test with binominal distribution. Fleiss' fixed‐marginal κ was calculated to estimate the overall inter‐rater agreement (30 centres (raters), 18 (6 cases × 3 risk factor scenarios) case scenarios). A κ value below 0·40 was considered poor, 0·40–0·75 as intermediate to good, and more than 0·75 as excellent. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. SPSS® version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

Results

Thirty‐two centres were contacted and 30 participated in the study (Table S1 , supporting information). Characteristics of the 30 participating centres are shown in Table 1. All centres were presented with three MRCP images (cases A, B and C) within the criteria of a Todani type 1 choledochal cyst (Fig. 1 a–c). Case A, with a 13‐mm CDB dilatation, was interpreted as a Todani type 1 cyst, Todani type 4 cyst and a physiological variant by two (7 per cent), three (10 per cent) and 25 (83 per cent) centres respectively. Case B, with a 20‐mm CDB dilatation, was interpreted as a Todani type 1 cyst, Todani type 4 cyst and a physiological variant by 28 (93 per cent), one (3 per cent) and one (3 per cent) centres respectively. Case C, with a 26‐mm CDB dilatation, was interpreted as a Todani type 1 cyst, Todani type 4 cyst and a physiological variant by 25 (83 per cent), five (17 per cent) and no centres respectively. The responses as to whether to resect or not are summarized in Fig. S1 (supporting information).

Table 1.

Characterization of contributing centres

| No. of centres (n = 30) | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Denmark | 3 |

| England | 4 |

| Finland | 3 |

| Ireland | 1 |

| The Netherlands | 7 |

| Norway | 5 |

| Scotland | 1 |

| Sweden | 6 |

| HPB resections/year | |

| < 200 | 13 |

| ≥ 200 | 17 |

| Centre HPB profile | |

| Liver | 1 |

| Pancreas | 1 |

| Liver and pancreas | 28 |

| Discussed by multidisciplinary team | |

| Yes | 12 |

| No | 18 |

HPB, hepatopancreatobiliary.

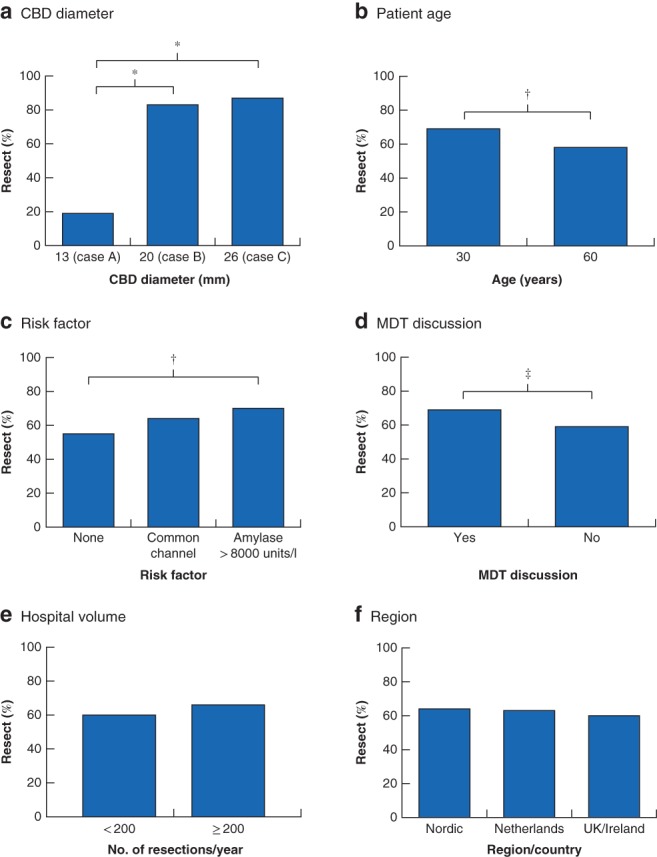

When considering all six cases (combination of duct size and age) and the three different risk factor scenarios (no risk factor, common channel and amylase level above 8000 units/l in bile duct aspirate), resection was recommended more often for cases B and C (83·3 per cent and 86·7 per cent respectively) than for case A (19·4 per cent) (both P < 0·001). There was no difference when case B was compared with case C (P = 0·376) (Fig. 2 a). Increasing age had an inverse impact on the recommendation to resect. For all cases and scenarios, 68·5 per cent would recommend resecting a 30‐year‐old patient, compared with 57·8 per cent for a 60‐year‐old patient (P = 0·010) (Fig. 2 b). When asked about risk factors, 55·0 per cent would recommend resection in the absence of any risk factor, compared with 64·4 per cent in the presence of a common channel (P = 0·068), and 70·0 per cent in the presence of an amylase level above 8000 units/l in aspirate from the CBD (P = 0·003 versus no risk factor) (Fig. 2 c). The 12 centres that discussed resection in an MDT meeting recommended resection more often than the 18 centres that did not (69·0 versus 59·3 per cent respectively; P = 0·022) (Fig. 2 d). The 13 centres that performed fewer than 200 HPB resections and the 17 centres performing 200 or more HPB resections recommended CBD resection in 59·9 per cent and 66·0 per cent respectively of the cases and scenarios (P = 0·146) (Fig. 2 e). There were no regional differences for the recommendation to resect: 64·4, 62·7 and 60·2 per cent from the Nordic countries (17 centres), the Netherlands (7 centres) and the UK/Ireland (6 centres) respectively (P ≥ 0·437) (Fig. 2 f).

Figure 2.

Results for all case scenarios combined Percentage of responses recommending resection in the case scenarios of a common bile duct (CBD) diameter, b patient age, c absence or presence of risk factors, d use of multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussions, e size of the centre with respect to the annual number of hepatopancreatobiliary resections performed, and f the northern European region. *P < 0·001, †P ≤ 0·010, ‡P < 0·050 (χ2 test).

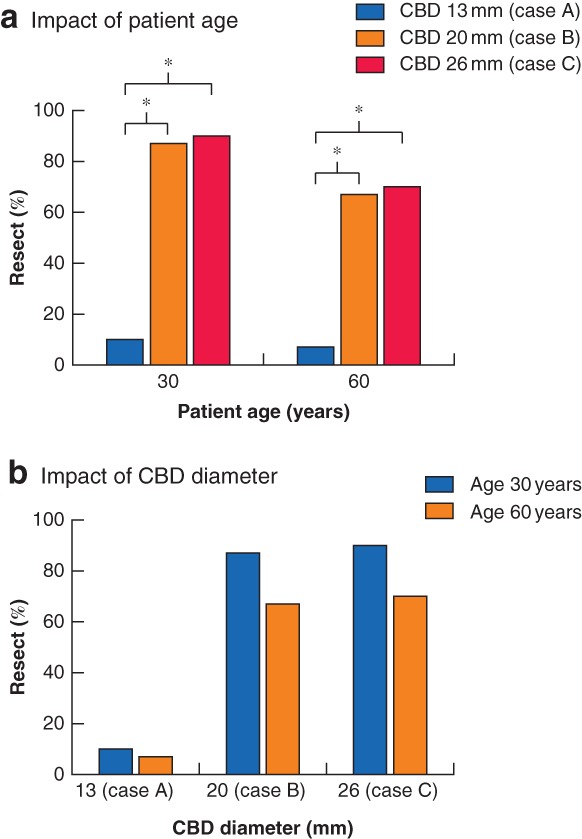

When considering the answers before the additional information about any risk factor alone, there was a similar pattern in the recommendation of resection based on the age of the patient and diameter of the CBD (cases A–C). For a 30‐year‐old patient, three (10 per cent), 26 (87 per cent) and 27 (90 per cent) of the 30 centres would recommend resection of a 13‐mm (case A), 20‐mm (case B) and 26‐mm (case C) CBD dilatation respectively: P < 0·001 (A versus B and C) and P = 0·687 (B versus C) (Fig. 3 a). For a 60‐year‐old patient, two (7 per cent), 20 (67 per cent) and 21 (70 per cent) centres would recommend resection of a 13‐, 20‐ and 26‐mm CBD dilatation respectively: P < 0·001 (A versus B and C) and P = 0·781 (B versus C) (Fig. 3 a). Fig. 3 b depicts the impact of age for each CBD diameter; there were no significant differences (case A, P = 0·639; case B, P = 0·067; case C, P = 0·053).

Figure 3.

Impact of age and common bile duct diameter on recommendation for resection Percentage of responses recommending resection in the absence of any risk factor, showing the impact of a patient age and b diameter of the dilated portion of the common bile duct (CBD). *P < 0·001 (χ2 test).

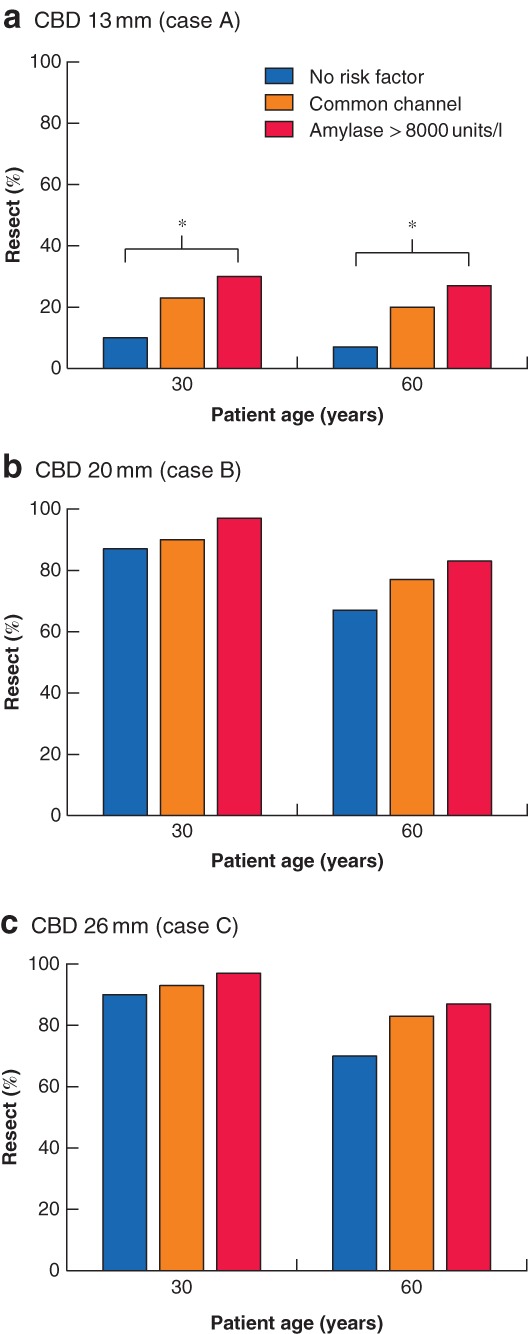

Participating centres were asked to give their answers in the absence and presence of a common channel or amylase concentration above 8000 units/l in aspirate from the CBD. For case A, the 13‐mm CBD dilatation, there was a trend towards more resection in the presence of a common channel, irrespective of age (30 years: 3 (10 per cent) versus 7 (23 per cent); 60 years: 2 (7 per cent) versus 6 (20 per cent) of the 30 centres; both P = 0·125) (Fig. 4 a). For the same CBD dilatation, amylase in the CBD was associated with more recommendations to resect compared with no risk factor, irrespective of age (30 years: 3 (10 per cent) versus 9 (30 per cent); 60 years: 2 (7 per cent) versus 8 (27 per cent) of 30 centres; both P = 0·031) (Fig. 4 a). For cases B and C (CBD dilatations of 20 and 26 mm), there were only trends towards more resection recommendations for the risk factor scenarios; these were more pronounced for the 60‐year‐old patient (Fig. 4 b–c).

Figure 4.

Impact of the presence of a common channel or amylase in the aspirate from the common bile duct on recommendation for resection Percentage of responses recommending resection in the presence or absence of a common channel or amylase level above 8000 units/l, stratified by patient age and common bile duct (CBD) dilatation: a CBD 13 mm (case A), b CBD 20 mm (case B), c CBD 26 mm (case C). *P < 0·050 (χ2 test).

The overall inter‐rater agreement between the 30 centres for the 18 case scenarios was 73·3 per cent with a κ value of 0·43 (95 per cent c.i. 0·38 to 0·48).

Discussion

In the this study, the inter‐rater agreement between 30 northern European HPB centres with respect to their recommendation whether to resect a fusiform dilatation of the CBD in different cases and risk factor scenarios was investigated. Although there were no regional differences or differences related to the size of the HPB unit (measured in terms of annual HPB resections), there was intermediate agreement with a Fleiss κ value of 0·43. This finding may indicate a need to highlight the difficulty of certain diagnoses and the timing and role of surgery in these rare cases.

The Todani classification is based on radiological imaging of the location and shape of the cyst, rather than size, and does not define when a fusiform dilatation becomes a true choledochal cyst with malignant potential. The recommendation to resect is also based on the Todani classification, which may not be appropriate for the purpose of surgical decision‐making. For instance, in the present study, case A was defined by external radiologists as a Todani type 1 choledochal cyst, thus with an implicit indication for resection. Interestingly, the surveyed consultant HPB surgeons, confronted with the question of resection, assessed this fusiform dilatation as a physiological variant (25 of 30 centres). As such, there may be interpretation differences between radiologists and surgeons, the latter possibly avoiding a disagreement with guidelines recommending resection. Taken together, this survey suggests one of two interpretations: either that the link between a Todani type 1 cyst and risk of development of cancer is not readily accepted for subtle fusiform dilatations (for example 13 mm or less) or that the definition of a type 1 cyst is incomplete and lacks a lower cut‐off diameter for fusiform and asymptomatic cases. For the surgeon, this means that, for subtle cases, the current definitions may not provide a satisfactory grounding on which to base a recommendation for resection.

There are a number of theories explaining the aetiology and pathogenesis of choledochal cysts. Babbitt's theory of the ‘common channel’ is that most accepted in the literature19. According to this theory, the common channel is formed by an APBDU, which results in reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct and activation of pancreatic enzymes causing inflammation and deterioration of the bile duct wall, leading to biliary dilatation. In patients with choledochal cysts, associations between the amylase level, earlier presentation and dysplasia grade have been reported8, 20. It is known that immature neonatal pancreatic acini do not produce sufficient pancreatic enzymes to explain antenatal choledochal cysts21. However, assessment of amylase in the bile duct may be an easy way to determine whether pancreatic reflux is present, and may help the surgeon in decision‐making8. In the present study, participating centres were asked to give their recommendation in the presence of high levels of amylase in aspirate from the CBD. The significance of such a finding is still insufficiently explored to implement bile aspiration as a routine, and the question may therefore be somewhat more theoretical than practical. The possibility of other biomarkers in bile associated with cancer transformation would be interesting to explore in future research protocols.

The literature on choledochal cysts is limited by single‐institution experiences, and little is known about presentation, management and long‐term outcomes in the adult European population. Moreover, there have been concerns that, even after cyst excision, the risk of malignancy remains in the bile duct epithelium remote from the cyst, and increases during long‐term follow‐up3, 4, 18. In children, a questionnaire‐based survey among Dutch paediatric surgeons demonstrated a wide variety of opinions regarding diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up, indicating that these challenges are not exclusive to adults22.

A recently published meta‐analysis13 reported the risk of developing malignancy in choledochal cysts as 11 per cent, and recommended complete surgical resection of extrahepatic bile ducts rather than cystic drainage, as the latter increases the risk of developing biliary malignancy. However, 12 of the 18 studies included in the meta‐analysis originated from Asian countries (4 from North America and 2 from France). In contrast, a recent study from China23 claimed that proper bile flow, rather than radical excision of the choledochal cyst, is the most critical factor determining treatment outcome. Thus, the optimal surgical treatment may still need to be determined. Furthermore, these studies did not define the ethnicity of the patients and, as the Asian population in North America is significant, the risk of malignant transformation in the Western Caucasian population is not well documented.

The present study has the following limitations. First, the shapes of the three choledochal cyst cases presented were slightly different: case A was more delineated as a fusiform shape of the CBD, whereas cases B and C had a more cystic appearance. Consequently, the impact of size must be interpreted with caution and is likely also to have been affected by the interpretation of shape. Second, for the majority of the centres, the cases were interpreted by a single HPB surgeon (albeit in a leading position) and their answers may not strictly reflect clinical practice. Twelve centres discussed the images in a MDT setting and recommended resection more often. One explanation could be that the decision to resect a benign lesion, with a not insignificant potential of morbidity (and mortality), may be easier to make as a group. In addition, the recommendation to perform a resection may be more straightforward for a theoretical case than in clinical practice, and may have led to more recommendations to resect. Finally, as the majority would resect case B and the majority would not resect case A, there seems to be a grey zone between 13 and 20 mm. In retrospect, a case within this interval would be interesting to reveal possibly even greater disagreement. Further, it could have been emphasized that the patients in the cases had no previous history of gallstones (no cholecystectomy), tumour or inflammation – information that may have influenced decision‐making.

Northern European HPB surgeons do not base their decision to resect strictly on the radiological definition of a Todani type 1 or 4 choledochal cyst. There was a marked lack of consistency in the way the discrete dilatations were classified. The malignancy potential of difficult‐to‐define fusiform CBD dilatations is uncertain; this could be problematic and may call for revision of current surgery guidelines. Furthermore, the inter‐rater agreement to resect three fusiform CBD dilatations was intermediate. Patient age, the diameter and, possibly, the shape of the CBD dilatation appeared to dictate the recommendation to resect. Choledochal cysts are rare in the adult Western population. The rarity of the condition, the lack of symptoms and the long delay in potential development of cancer all pose significant methodological challenges to further studies, and probably indicate that a prospective registry may not be feasible. The findings of this study point to the need to refine international definitions and explore novel biomarkers in order to estimate more accurately the malignancy risk and optimal treatment of choledochal cysts in the asymptomatic non‐Asian adult population.

Supporting information

Table S1 HPB centres in northern Europe that participated in the study

Fig. S1 Summary of responses regarding resection for the 30 centres

Thirty centres were asked to resect (blue) or not resect (orange) a fusiform dilatation of the bile duct. Rows represent the participating centres stratified on volume of annual HPB resections. Answers stratified on patient age (30 or 60 years) and case (with diameter of the dilated portion of the CBD: 13, 20 or 26 mm). O: No common channel, no bile aspiration performed. C: Common channel more than 10 mm from the duodenal wall present (no bile aspiration performed). A: Aspiration of bile performed with amylase level above 8000 units/l (no common channel).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to all contributing centres.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding information

No funding

References

- 1. Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, Boitnott JK, Cameron JL. Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yamaguchi M. Congenital choledochal cyst analysis of 1433 patients in the Japanese literature. Am J Surg 1980; 140: 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bismuth H, Krissat J. Choledochal cystic malignancies. Ann Oncol 1999; 10(Suppl 4): 94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soares KC, Kim Y, Spolverato G, Maithel S, Bauer TW, Marques H et al Presentation and clinical outcomes of choledochal cysts in children and adults: a multi‐institutional analysis. JAMA Surg 2015; 150: 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jang SM, Lee BS, Kim KK, Lee JN, Koo YS, Kim YS et al Clinical comparison of choledochal cysts between children and adults. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2011; 15: 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babbitt DP, Starshak RJ, Clemett AR. Choledochal cyst: a concept of etiology. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973; 119: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kato T. Etiological relationships between choledochal cyst and anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system. Keio J Med 1989; 38: 136–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ragot E, Mabrut JY, Ouaissi M, Sauvanet A, Dokmak S, Nuzzo G et al Pancreaticobiliary maljunctions in European patients with bile duct cysts: results of the multicenter study of the French Surgical Association (AFC). World J Surg 2017; 41: 538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iwai N, Yanagihara J, Tokiwa K, Shimotake T, Nakamura K. Congenital choledochal dilatation with emphasis on pathophysiology of the biliary tract. Ann Surg 1992; 215: 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagi B, Kochhar R, Bhasin D, Singh K. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the evaluation of anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary duct and related disorders. Abdom Imaging 2003; 28: 847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kimura K, Ohto M, Ono T, Tsuchiya Y, Saisho H, Kawamura K et al Congenital cystic dilatation of the common bile duct: relationship to anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1977; 128: 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts. Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty‐seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg 1977; 134: 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ten Hove A, de Meijer VE, Hulscher JBF, de Kleine RHJ. Meta‐analysis of risk of developing malignancy in congenital choledochal malformation. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 482–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jan YY, Chen HM, Chen MF. Malignancy in choledochal cysts. Hepatogastroenterology 2000; 47: 337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voyles CR, Smadja C, Shands WC, Blumgart LH. Carcinoma in choledochal cysts. Age‐related incidence. Arch Surg 1983; 118: 986–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Atkinson HD, Fischer CP, de Jong CH, Madhavan KK, Parks RW, Garden OJ. Choledochal cysts in adults and their complications. HPB (Oxford) 2003; 5: 105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lenriot JP, Gigot JF, Segol P, Fagniez PL, Fingerhut A, Adloff M. Bile duct cysts in adults: a multi‐institutional retrospective study. French Associations for Surgical Research. Ann Surg 1998; 228: 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee SE, Jang JY, Lee YJ, Choi DW, Lee WJ, Cho BH et al; Korean Pancreas Surgery Club. Choledochal cyst and associated malignant tumors in adults: a multicenter survey in South Korea. Arch Surg 2011; 146: 1178–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Babbitt DP. Congenital choledochal cysts: new etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of the common bile duct and pancreatic bulb. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1969; 12: 231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jeong IH, Jung YS, Kim H, Kim BW, Kim JW, Hong J et al Amylase level in extrahepatic bile duct in adult patients with choledochal cyst plus anomalous pancreatico‐biliary ductal union. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 1965–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts: part 1 of 3: classification and pathogenesis. Can J Surg 2009; 52: 434–440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van den Eijnden MH, de Kleine RH, Verkade HJ, Wilde JC, Peeters PM, Hulscher JB. Controversies in choledochal malformations: a survey among Dutch pediatric surgeons. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2015; 25: 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xia HT, Yang T, Liu Y, Liang B, Wang J, Dong JH. Proper bile duct flow, rather than radical excision, is the most critical factor determining treatment outcomes of bile duct cysts. BMC Gastroenterol 2018; 18: 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 HPB centres in northern Europe that participated in the study

Fig. S1 Summary of responses regarding resection for the 30 centres

Thirty centres were asked to resect (blue) or not resect (orange) a fusiform dilatation of the bile duct. Rows represent the participating centres stratified on volume of annual HPB resections. Answers stratified on patient age (30 or 60 years) and case (with diameter of the dilated portion of the CBD: 13, 20 or 26 mm). O: No common channel, no bile aspiration performed. C: Common channel more than 10 mm from the duodenal wall present (no bile aspiration performed). A: Aspiration of bile performed with amylase level above 8000 units/l (no common channel).