ABSTRACT

Background

Individuals on hemodialysis bear substantial symptom burdens, but providers often underappreciate patient symptoms. In general, standardized, patient-reported symptom data are not captured during routine dialysis care. We undertook this study to better understand patient experiences with symptoms and symptom reporting. In exploratory interviews, we sought to describe hemodialysis nurse and patient care technician perspectives on symptoms and symptom reporting.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 42 US hemodialysis patients and 13 hemodialysis clinic personnel. Interviews were conducted between February and October 2017 and were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

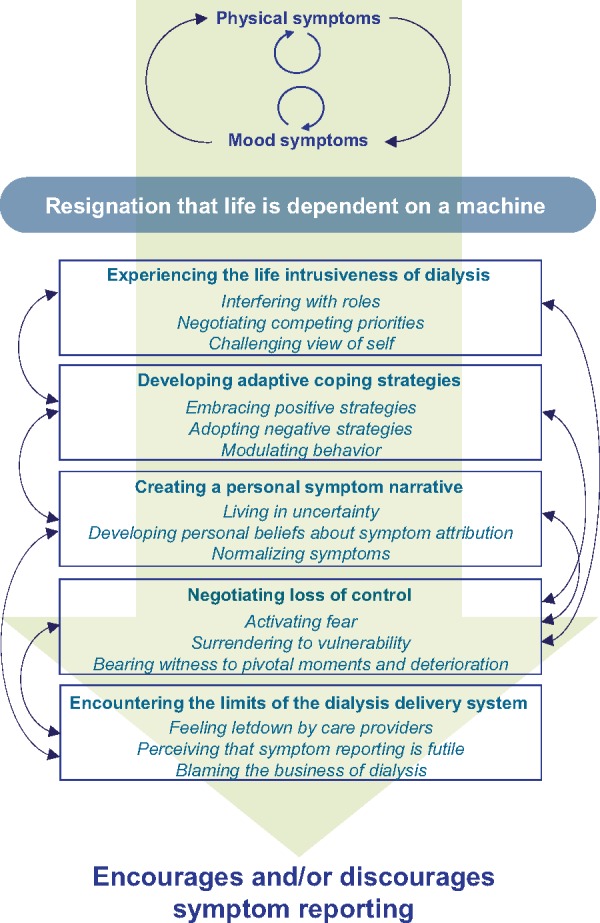

Seven themes were identified in patient interviews: (i) symptoms engendering symptoms, (ii) resignation that life is dependent on a machine, (iii) experiencing the life intrusiveness of dialysis, (iv) developing adaptive coping strategies, (v) creating a personal symptom narrative, (vi) negotiating loss of control and (vii) encountering the limits of the dialysis delivery system. Overall, patient symptom experiences and perceptions appeared to influence symptom-reporting tendencies, leading some patients to communicate proactively about symptoms, but others to endure silently all but the most severe symptoms. Three themes were identified in exploratory clinic personnel interviews: (i) searching for symptom explanations, (ii) facing the limits of their roles and (iii) encountering the limits of the dialysis delivery system. In contrast to patients, clinic personnel generally believed that most patients were inclined to spontaneously report their symptoms to providers.

Conclusions

Interviews with patients and dialysis clinic personnel suggest that symptom reporting is highly variable and likely influenced by many personal, treatment and environmental factors.

Keywords: communication, end-stage kidney disease, hemodialysis, interviews, symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Individuals receiving maintenance hemodialysis bear substantial symptom burdens that adversely affect health-related quality of life and other health outcomes. Physical symptoms such as fatigue, itching and cramping rank highly among the, on average, 11 symptoms experienced by hemodialysis patients [1]. Despite the importance of symptoms to patients, medical providers often underappreciate symptoms [2, 3]. Additionally, data suggest that patients desire more interaction with their providers about symptoms [4].

A recent randomized clinical trial among cancer patients found that standardized collection of patient-reported symptoms can improve quality of life and other health outcomes [5]. In most US dialysis clinics, standardized symptom data is captured at least annually via the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) symptom subscale. However, some patients question how these data are used to improve their experiences [6]. Informal symptom evaluations during routine clinical assessments occur more frequently, but data collection and reporting is not standardized. Moreover, symptom characteristics, patient beliefs and historical experiences may influence spontaneous symptom reporting tendencies [7]. Understanding patient perspectives on dialysis treatment-related symptoms and symptom reporting may inform approaches to symptom data collection in dialysis clinics.

We undertook this study to characterize patient beliefs about and experiences with hemodialysis-related symptoms and symptom reporting. In exploratory analyses, we aimed to describe dialysis nurse and patient care technician (PCT) perspectives on patient symptoms and symptom reporting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (COREQ; Supplementary data, Table S1) [8]. This study was approved by the University of North Carolina (NC) at Chapel Hill and University of Virginia (VA) Institutional Review Boards (studies 17-0038 and 19928). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participant selection

Individuals receiving maintenance hemodialysis were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years old, had been receiving in-center hemodialysis for ≥6 months and were English speaking. Individuals with cognitive impairment or who were medically unstable as per their treating nephrologists were excluded. Hemodialysis nurses and PCTs were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years old, had ≥6 months hemodialysis patient care experience and were English speaking. A purposive, iterative sampling strategy was used to capture a range of demographic characteristics (age, sex, race and dialysis vintage), symptom experiences and professional roles (nurse versus PCT).

Participants were recruited from three NC dialysis clinics, two VA dialysis clinics and national patient mailing lists. Patient recruitment methods included study fliers posted in dialysis clinics, in-person recruitment by study staff and e-mails to advocacy organization members (Renal Support Network) and select End-Stage Renal Disease Network Patient Advisory Committees (Networks 2, 3, 14, 16, 17 and 18). These latter sources were selected to capture patients residing outside the southeastern USA. Clinic personnel recruitment methods included study fliers posted in dialysis clinics, announcements at staff meetings and in-person recruitment. Study staff screened interested individuals for eligibility and obtained informed consent. All participants were reimbursed $25 for their time.

Data collection

We developed a semi-structured interview guide based on literature review and team discussions (Supplementary data, Table S2). The guide included questions on dialysis-related symptom experiences and symptom reporting. Clinic personnel were asked to respond to questions based on their experience caring for hemodialysis patients. Interview questions were open-ended, and participants were encouraged to provide examples and expand on their responses. Interviews were conducted from February to October 2017 by two experienced interviewers (A.D., J.H.N.). Interviews with participants from NC and VA were conducted in-person, and interviews with participants elsewhere were conducted by telephone. In-person interviews occurred in private dialysis clinic conference rooms. Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. Field notes were taken by the interviewers. Participant characteristics were self-reported.

Data analysis

Transcribed interviews were entered into ATLAS.ti software for data organization and coding purposes (Version 7, Berlin, Germany). Using thematic analysis rooted in the principles of Braun and Clarke [9, 10], two study team members (A.D., J.E.F.) read the transcripts line by line, inductively identified concepts and coded the relevant interview text by concept. Related concepts were synthesized into themes and subthemes with input from three team members (A.D., J.E.F, J.H.N.). The team identified conceptual patterns among the themes and developed a thematic schema. Concepts were iteratively discussed by the research team at regular meetings to ensure that the theming reflected the interview data depth (researcher triangulation). During these discussions, the team returned to the source data (transcripts) to verify findings and ensure theming accurately reflected the data.

Patient interviews were ceased when no new codes were identified after three consecutive interviews (data saturation). Dialysis clinic personnel interviews were considered exploratory and stopped after exhaustion of the convenience sample of available staff at participating NC and VA dialysis clinics. Data saturation was not attempted in these interviews.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics and symptom descriptions

Table 1 displays participant characteristics. Of the 60 hemodialysis patients invited to participate, 42 (70%) participated. Of the 18 clinic personnel invited to participate, 13 (72%) participated. Among patients, the mean (± SD) age was 57 ± 13 years, mean hemodialysis vintage was 7 ± 7 years, 23 (54.8%) were female and 23 (54.8%) were black. Among clinic personnel, 4 (31%) were nurses and 9 (69%) were PCTs; the mean time in current role was 7 ± 7 years. Patients described a range of dialysis treatment-related symptoms including post-dialysis fatigue, cramping, thirst and lightheadedness, among others (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient and dialysis clinic personnel participant characteristics

| Characteristica | n (%) or mean ± SD; median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Patient participants (n = 42) | |

| Age (years) | 57.3 ± 12.8; 58.5 (51.0–67.3) |

| Female | 23 (54.8) |

| Race | |

| White | 15 (35.7) |

| Black | 23 (54.8) |

| Other | 4 (9.5) |

| Diabetes | 17 (40.5) |

| Heart failure | 14 (33.3) |

| Cancer | 3 (7.1) |

| Dialysis vintage (years) | 7.2 ± 6.9; 4.5 (3.4–9.0) |

| Typical ultrafiltration volume (L) | 2.7 ± 1.0; 2.5 (2.0–3.3) |

| Prescribed treatment time (min) | 234.3 ± 31.8; 240 (210–240) |

| Typical time to recovery after hemodialysis (h) | |

| <2 | 13 (31.0) |

| 2–6 | 15 (35.7) |

| 7–12 | 5 (11.9) |

| >12 | 9 (21.4) |

| Location of dialysis clinic | |

| North Carolina | 16 (38.1) |

| Virginia | 15 (35.7) |

| Connecticut | 3 (7.1) |

| New York | 1 (2.4) |

| New Jersey | 2 (4.8) |

| Delaware | 1 (2.4) |

| Texas | 1 (2.4) |

| California | 2 (4.8) |

| Washington | 1 (2.4) |

| In-person interview | 31 (73.8) |

| Interview length (min) | 29.5 ± 12.0; 27.3 (20.1–38.0) |

| Nurse and PCT participants (n = 13) | |

| Age (years) | 35.7 ± 12.8; 33.0 (23.5–48.5) |

| Female | 9 (69.2) |

| Race | |

| White | 10 (76.9) |

| Black | 1 (7.7) |

| Other | 2 (15.4) |

| Dialysis nurse | 4 (30.8) |

| Length of time in current role (years) | 7.0 ± 7.0; 5.0 (2.0–9.3) |

| Location of dialysis clinic | |

| North Carolina | 9 (69.2) |

| Virginia | 4 (30.8) |

| In-person interview | 13 (100) |

| Interview length (min) | 29.8 ± 7.4; 30.3 (24.4–34.4) |

All comorbid conditions and hemodialysis treatment data were self-reported.

IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2.

Patient descriptions of hemodialysis-related symptoms

| Symptom | Quotationsa |

|---|---|

| Post-dialysis fatigue | ‘It’s like something’s sitting up on your shoulders and you can’t wait to get home to lay down. It’s terrible.’ (58 years, male) |

| ‘Well when I go in, I can come hopping in. When I leave- unh-uh. Getting up out of that chair, walking to the scale even is an effort.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘If I don’t go home and lay down, I feel like a drunk man. I feel worse and worse and worse. I have to lay down. I get that no good feeling. I don’t feel normal. You feel like something coming over. You’ve got to sit down or lay down or something. Then, after you get that nap in, you’re good to go, but I can’t leave here and be up all day. I can’t do that.’ (68 years, male) | |

| Cramping | ‘Well for me, I can give it to you on a scale from one to ten. It was about a twelve. To be honest, it’s made grown men cry. Cramping is very severe for a lot of people.’ (70 years, female) |

| ‘As soon as the cramps start, I'm yellin'. You never die, but it’s so painful you think that you do.’ (71 years, female) | |

| ‘It hurts like hell and when it stops, there’s nothing that you can do to try and avoid it again … With me it starts in the toes and it feels like—you know how you roll up a toothpaste tube? That’s how it feels. Your toes are starting to curl up… The muscles react and they contract… You don’t feel it until you just feel it. It hurts. It’s very painful. It’s very painful. It’s hurting. It’s twenty times on a scale of one to ten.’ (53 years, male) | |

| Thirst | ‘And I have my cup of ice. A lot of people just love that ice… [Not having ice] would be devastating, because I love that ice, I do. I look forward to the ice. I sit there and chomp on it. It wets my whistle. It makes me less thirsty.’ (67 years, female) |

| ‘I’m always thirsty because of the fluid restrictions. During treatment, I do ice. I also chew gum, regular gum, bubblegum and try to keep myself as occupied as possible. The thirst never really goes away. I have cottonmouth.’ (59 years, female) | |

| Dizziness or lightheadedness | ‘Well I told them it’s not like the world is spinning. It’s like it’s waving. I mean that’s the way it feels. I look at things, and I sit there and watch the cows out in the field and they’re just doing this… going up and down.’ (76 years, female) |

| ‘Well, it’s a vision, too, but you’re really lightheaded, you’re just going to space out, you know. I looked at the tech and my eyes were—she was getting blurry, and my speech can get mumbled when it’s so severe.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘Lightheadedness makes me stagger. I have to walk out with a cane in order to keep from falling.’ (77 years, male) | |

| Headache | ‘It feels like somebody’s taking a hammer and hitting me upside the head.’ (39 years, male) |

| ‘It’s just a dull ache up on the top of my head, at the very top of my head.’ (66 years, male) | |

| ‘You feel like there’s Indians, and drummers, and anybody else in your head. If somebody asks me a question, I very slowly move my head because it hurts down into my neck. I mean, my neck feels sore.’ (68 years, female) | |

| Nausea | ‘I get a stomachache; it’s one of the things with dialysis.’ (67 years, female) |

| ‘[Dialysis will] make your stomach feel like you got butterflies in it… you know, my stomach problems can last till the next day if I’m really over my dry weight.’ (65 years, male) | |

| ‘My stomach will be bubbly.’ (53 years, female) | |

| Numbness or tingling | ‘[Tingling] feels like—you know how a bug will kind of—you feel a bug flying on you? That tingle? It’s that kind of tingle.’ (64 years, female) |

| ‘I experience tingling in my feet and the lower part of my legs. Also in my hands… The right hand if it gets cold, it’s on. I mean I have to literally stick my hand under here, under my bust line, or go run my hand under some warm water to get the sensation to go.’ (59 years, female) | |

| Shortness of breath | ‘Feels like somebody’s sitting on my chest, I can’t breathe.’ (56 years, female) |

| ‘It feels terrible because sometimes I'll be gasping for breath, and it's hard for me to catch my breath. I get upset about it. I start crying because I can't breathe. It's like my own lungs is shutting down, and I just can't get the breath that I need.’ (49 years, female) | |

| ‘I just kind of panic when I can’t get a deep breath. It’s like I feel like I’m going to smother.’ (76 years, female) | |

| Itching | ‘[Itching] is the most uncomfortable feeling in the world, because you can’t move around. You can’t scratch or nothing else. You’ve got to wait on the girls to come… You’ve got to take [fluid] off so, you’ve got to deal with it… after and during the session and stuff.’ (55 years, male) |

| ‘Oh gosh, I itch… I just have to sit there and scratch my head, and it’s like you want to put your back up against the wall and just itch, you know? Like a bear against a trunk of a tree, you know?’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘Terrible, terrible itching… it was really relentless at one time. I had open sores on my skin. It felt better to bleed. It would itch so much I would scratch until I bled, and even that felt better, just the bleeding, just to get the sensation of itching off of me.’ (59 years, female) | |

| Heart palpitations | ‘[Heart palpitations] could be a killer in more ways than one. Sometimes I’ve gotten chest pains and my pulse goes way up.’ (67 years, female) |

| ‘My heart feels like it’s going to jump out of my body and my body is saying calm down, calm down. (76 years, female) | |

| ‘I’m like oh my god, am I having a heart attack? What’s going on? It’s scary. The fluttering of the chest is scary.’ (34 years, female) |

Quotations are from patient participants.

Patient interview themes and subthemes

We identified seven major themes: symptoms engendering symptoms, resignation that life is dependent on a machine, experiencing the life intrusiveness of dialysis, developing adaptive coping strategies, creating a personal symptom narrative, negotiating loss of control and encountering the limits of the dialysis delivery system. Table 3 displays illustrative quotations for the identified themes and subthemes. Figure 1 presents a schematic of the conceptual links among themes and illustrates how themes may relate to patient symptom-reporting tendencies.

Table 3.

Illustrative patient quotations for identified themes and subthemes

| Themes and subthemes | Quotationsa |

|---|---|

| Symptoms engendering symptoms | |

| ‘It’s that emotional thing and then if you’re going to do it right there’s the physical adjusting to the lifestyle… because [the symptoms] are all intertwined. They’re all intertwined.’ (53 years, male) | |

| ‘The flutters give me the anxiety because I don’t know what’s going on.’ (34 years, female) | |

| ‘I feel like I’m tired all the time. I feel like I don’t have the energy to play with my grandchildren or do stuff. It makes me depressed.’ (56 years, female) | |

| ‘I think about the symptoms that I’m feeling like the dizziness and stuff. It makes me nervous.’ (34 years, female) | |

| Resignation that life is dependent on a machine | |

| ‘I’m glad I’m on dialysis. Cause the other option is not good. I mean, if I don’t go to dialysis, I’m going to be dead. Dialysis has taken care of that problem for me.’ (79 years, male) | |

| ‘I think of dialysis as my way of having a life. I’m still in the land of living and that’s very important to me. I don’t think about the affect it is having on me. As long as I’m still in the land of the living and nobody is shoving dirt over me, I’m fine.” (59 years, female) | |

| ‘I look at it this way, I know that I need dialysis to live, but it is frustrating because of the symptoms, not just sitting there in the facility receiving the treatment, but the symptoms that I go through are frustrating.’ (34 years, female) | |

| Experiencing the life intrusiveness of dialysis | |

| Interfering with roles | |

| ‘Well, yeah, cause [dialysis] got you—I’m at home five hours sleeping. That mean I ain’t doing nothing. It interferes with everything. I can’t wash my car, I can’t go open my fishing business up to sell, I don’t go sightseeing, it’s just the whole day’s shot pretty much. (52 years, male) | |

| ‘I couldn't go with my friend the other night because he wanted to go for a walk and I knew I wasn't going to make it, so I didn't go.’ (58 years, female) | |

| ‘I used to work when I got home, but now I got to take a rest. After you get off the machine, your body’s so drained. There’s not much you can do. You just want to rest.’ (48 years, male) | |

| ‘It gets in the way of cooking, chores. Also I’m a student. I’m pursuing my master’s degree so it gets in the way of me doing my schoolwork. I have to wait until the next day. Pretty much after dialysis treatment, I don’t have the energy to do anything.’ (34 years, female) | |

| ‘I mean, one of the most noticeable things that I’ve experienced from being on dialysis is after dialysis my endurance is basically cut in half.’ (30 years, male) | |

| Negotiating competing priorities | |

| ‘I get up early because I’ve got to be in [dialysis] early. So that routine’s already there. And I try not to take a nap during the day on those days because I want to sleep at night.’ (56 years, female) | |

| ‘Mostly, I don’t do anything much. Like the day I have off, I try to cook enough to have for the next night, so that way I don’t have that much to do [on dialysis days].’ (74, years, female) | |

| ‘A lot of times we have to kind of weigh the risks and the benefits of what we want to do and what we know we should do.’ (54 years, female) | |

| ‘When my family has something going on, like a birthday party, they don’t do it on a Saturday because they know that I’m not going to be able to be there with them. So we’ll do things on Sunday to make it better.’ (56 years, female) | |

| Challenging view of self | |

| ‘I’m a bit of a control freak and I don’t like it when I’m not in control of my bodily functions and stuff.’ (30 years, male) | |

| ‘I push myself, but it's still hard… once I get out then I try not to come home and sleep. Sometimes I just get so tired I don't have a choice. I just fall asleep.’ (58 years, female) | |

| ‘I won’t let it [interfere]. I go home, I do the laundry, I cook supper, I sit down in between. I can’t keep going like I do on my days I’m off. I have to sit and rest in between my chores.’ (66 years, female) | |

| Developing adaptive coping strategies | |

| Embracing positive strategies | |

| ‘I have to be my own advocate and I have to be my own doctor, so when I don't feel good I have to tell them what I think it is because they don't really know. They can guess, and they can see on the outside, but they're not really feeling what I'm feeling on the inside and they don't know.’ (58 years, female) | |

| ‘In the beginning, I was very upset about having to be on dialysis and once I started and I knew that okay, well this is what I have to do, I kind of got my mind set that—I’m in this, let me make the best of it. I try to keep a positive attitude about it and this is the way I get through this. This is how I handle it.’ (70 years, female) | |

| ‘I don’t let things get in my way. I try to overcome everything. I did not used to have a positive attitude like I do now. Since I found the Lord, I’ve got a positive attitude.’ (55 years, male) | |

| ‘Well, I mean, you learn how to control [the thirst], you know, you eat ice and all that stuff instead of drinking a whole lot of fluids.’ (48 years, male) | |

| ‘… you can know your body, and tell them how much fluid you want to pull off. Just because the scales say one thing, you don’t have to get to that point. You learn your body, and know what you can do, and what you can’t do. So that makes a difference. You learn. You learn quick! You learn real quick to keep from being sick.’ (51 years, male) | |

| Adopting negative strategies | |

| ‘I like my chicken, baked chicken and stuff. And I like my hamburgers and hotdogs. They don’t want me to, but I eat hotdogs occasionally… It don’t bother me, but they don’t want me eating it.’ (53 years, female) | |

| ‘Well, I guess sometimes I’m on the pity pot. I’m on the pity pot, and it’s like why did this happen to me? And it’s like do I have to keep enduring all of this?’ (76 years, female) | |

| ‘I don’t ever want to come to dialysis, to tell you the truth. And, sometimes I don’t.’ (51 years, male) | |

| Modulating behavior | |

| ‘You got to change your lifestyle once you’re on this machine. You can’t just get up and do what you want to do.’ (48 years, male) | |

| ‘[Dialysis] is a big change. I’ve gotten better with treatment after I learned how to manage being on dialysis and what I have to do and not do as far as the cramping and the pressure dropping. It entails a lot of other underlying factors. Everything we ingest is measured. Anything that turns to liquid, we have to account for. I’m only allowed twenty-eight ounces per treatment. So, how I manage that is that I watch what I eat and what I drink. I try not to exceed what’s the limit that I’m supposed to have and I weigh myself as well before and after so that at least we seem to be in the same range.’ (70 years, female) | |

| ‘I try to stay away from the foods that cause the itching, like nuts and packaged foods and things of that nature. I was eating organic before, but I try to eat fresh fruits and vegetables as much as I can now.’ (59 years, female) | |

| ‘If I’m feeling lightheaded I’ll just drink a little bit more fluid, consume a little more sodium than usual, and then I will take it easy if I need to. Usually I’m on top of it and I’m pretty good at maintaining homeostasis.’ (30 years, male) | |

| Creating a personal symptom narrative | |

| Living in uncertainty | |

| ‘I’ve been trying to figure out my symptoms for three years now… so I have no idea. I can’t even give you an inkling, because I’ve got no clue.’ (34 years, female) | |

| ‘I have no clue [what causes cramps] because we’ve tried, our dialysis remedies of eating mustard or some salt. It just may be a part of your dialysis. I really don’t know because I think—what did they put me on? If it was a medicine they prescribed to see if it would work. It didn’t work.’ (59 years, female) | |

| ‘I think doctors need to have a more scientific approach to dialysis because I’ve noticed that there seems to be some disconnect between science and medicine.’ (30 years, male) | |

| ‘I mean, I don’t know, being on dialysis, everybody’s dialysis is different, so I can be normal and going in the street and all of a sudden I probably have an upset stomach or something. I don’t know where it come from. Can I point it to the diabetes? To the kidney? I don’t know, but I know your body do strange things when you’re on the kidney machine.’ (52 years, male) | |

| Developing personal beliefs about symptom attribution | |

| ‘My personal opinion is I think it's the water that they take out of your system, because the water regulates your blood pressure. So if they're taking out too much water, then that causes [lightheadedness]. So I had to ask to change my—what they call the dry weight. Because I had said to the doctor and the nurses, how do you know that's all fluid that's got to come off of me? Maybe I'm gaining weight and they're just taking out too much.’ (48 years, male) | |

| ‘It’s related because they’re flushing all your blood out your system. You got a foreign object going in your system and taking your blood out and running it back in, that’s like an oil tank. Basically instead of getting an oil change out of you they just didn’t send Jiffy Lube, they send dialysis.’ (48 years, male) | |

| ‘It [numbness] happens whenever I consume too much salt and too much sugar.’ (71 years, female) | |

| ‘The less [fluid] you take off, the better you feel. The more they take off, the worse you’re going to feel. The more fluid you got on, the more side effects you’re going to have.’ (51 years, male) | |

| Normalizing symptoms | |

| ‘… sometimes I do get a stomachache, it’s just one of the things with dialysis.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘It’s become routine. I go home and lay down. I don’t feel like cleaning, none of that stuff. Just be tired… I’m pretty tough, and you can say I’ve grown accustomed to it.’ (58 years, male) | |

| ‘Oh, I don't sleep hardly any more. I'm getting used to it, but it sucks.’ (58 years, female) | |

| Negotiating loss of control | |

| Activating fear | |

| ‘I think I’m going to pass out, it’s happened a couple of times and it scared the bejeebers out of me.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘These needles are so large and the experience to me is traumatic…’ (53 years, male) | |

| ‘The flutters give me the anxiety because I don’t know what’s going on. I’m like oh my god, am I having a heart attack? What’s going on? It’s scary.’ (34 years, female) | |

| ‘The most fearful is the breathing when you can’t breathe like you want to.’ (54 years, female) | |

| Surrendering to vulnerability | |

| ‘You know, we’re just helpless.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘You know, they turn off the lights, you're hooked up, you're not moving… you're sitting there, you can't move, your arm is there for three and a quarter hours because if you move the machine beeps, and then you try not to make the machine beep because it adds time, and nobody wants to have time added to their time. So you just sit there and deal with it for three hours and fifteen minutes.’ (59 years, female) | |

| ‘Just sitting in that chair is stress on the body, when you can’t move around and stuff… And sometimes, I just get uncomfortable or I’ll get restless legs. But when that happens, you can’t get up and move around.’ (67 years, female) | |

| Bearing witness to pivotal moments and deterioration | |

| ‘I had a guy that I was dialyzed with for a year and a half. He was in his forties in great shape. He was one of the healthiest dialysis patients I’ve seen… one Friday night he was in dialysis, went home and by the mid-morning the next Saturday, he had had a massive heart attack and died. It scared the hell out of me.’ (70 years, male) | |

| ‘But your fluid, boy that could just take you down fast… well that’s why some people in the unit, because they’re so overloaded and then if they also have a bad heart or something they start having chest pains and stuff and they end up going to the ER.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘I’ve seen how it affects other patients and I try not to put myself in that position. I try to limit my fluid.’ (70 years, female) | |

| Experiencing the limits of the dialysis delivery system | |

| Feeling letdown by care providers | |

| ‘And I think people are being trained to get the job done; they’re missing the empathy part. I think how the care is given needs to be looked at. Are you just doing the minimum or are we really doing things that will add to the quality of people’s lives? Are we really making a concerted effort to do that? I think not.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘I feel as though the physician needs to get to know the patient a little bit more intimately. Right now it’s—what do I want to call it—a line, a factory. A factory mill, a renal mill, where we just get them in, get them out, move on to the next patient. It’s sort of like that process right now so there’s not much attention to the intimate care of the patient from the physician. You’re dealing with people who are going through a traumatic experience so you’re going to have to get that human factor in there somewhere.’ (53 years, male) | |

| ‘Many patients experience these symptoms, but doctors really aren’t doing much to treat the symptoms.’ (30 years, male) | |

| ‘I said something to my doctor, and the doctor here, they can’t come up with nothing. They don’t seem to know what [the lightheadedness] is, but it got to be coming from something.’ (68 years, male) | |

| Perceiving that symptom reporting is futile | |

| ‘They do ask us things—how do you feel today when you first come in and stuff, but I don’t know if they always note it in your chart. If there’s low blood pressure, that is noted, but I don’t know where it goes from there, because nothing’s ever done. They do the pain management asking, like once a month, they don’t do anything with it. Supposedly they do review and watch for mental health, but they don’t do anything with it.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘If I come in here and I'm feeling bad or something and I tell them and they don't really like listen to me, I ain't going to say it like this to them if they really don't pay attention to me.’ (49 years, female) | |

| ‘They’re going to push the computer, go push the computer for what? They don’t do anything about it, so I feel it’s no use in telling if I get an upset stomach that night or I puked up.’ (52 years, male) | |

| Blaming the business of dialysis | |

| ‘Like Monday, I looked for the tech, because there wasn’t one right there. They’re so busy, they’re so overloaded, and were short staffed, that they were doing what they were supposed to, getting supplies and stuff. Finally I just rang my bell because I knew I was going to pass out or something bad was going to happen.’ (67 years, female) | |

| ‘There’s a high turnover rate here. The complexity of the job is such that you need well-seasoned people and that’s not happening here and I feel as though my health and safety is at risk. There is a lot of anxiety because you don’t know what you are going to get. The staff is under a lot of tremendous pressure to get things done right. Too much room for mistake and error.’ (53 years, male) | |

| ‘When I was younger, treatments were a bit more individualized, and then I had a transplant and once I got back on dialysis, dialysis was more streamlined. And that’s where the fault lies.’ (30 years, male) | |

Quotations are from patient participants.

FIGURE 1.

Thematic schema for patient interviews. Patients described perpetuating, interconnected physical and mood symptom cycles. A general resignation that their lives depended on machines appeared to influence how patients experienced these symptom cycles. This reality colored how patients understood, perceived and coped with symptoms as well as how they interacted with the dialysis care system. The figure displays the symptom cycle (first theme) as experienced through the lens of a machine-dependence reality (second theme). The remaining five themes (experiencing the life intrusiveness of dialysis, developing adaptive coping strategies, creating a personal symptom narrative, negotiating loss of control and encountering the limits of the dialysis delivery system) were experienced through this lens, which transformed and informed symptom experiences, perceptions and responses differently across patients. Bidirectional arrows indicate theme interrelationships. Collectively, the seven identified themes appeared to influence patient tendencies to report (versus not) symptoms to their care teams.

Symptoms engendering symptoms

Participants cited interconnections among symptoms: physical–physical, mood–mood and physical–mood symptoms. Examples included intradialytic cramping worsening post-dialysis fatigue, and, in turn, post-dialysis fatigue worsening depression. For many, depressive symptoms interfered with coping skills, further worsening physical symptoms. One patient described ‘symptom cycles’ that could be prompted by a single, poorly tolerated hemodialysis treatment.

Resignation that life is dependent on a machine

All participants expressed acceptance, usually resignation, that their lives were dependent on machines. This reality appeared to deeply influence participants’ perceptions of symptoms with many viewing symptoms as unavoidable consequences of a life-sustaining treatment. This sense of resignation both transformed and informed symptom experiences, coping strategies and reporting tendencies across all participants. For some, this acceptance sparked resiliency and positive, adaptive coping strategies such as proactive symptom reporting. For others, it brought frustration and negative, reactive coping strategies that often resulted in withholding symptoms from their care teams.

Experiencing the life intrusiveness of dialysis

Interfering with roles

Almost universally, hemodialysis treatment-related symptoms were viewed as having substantial life impact due to their interference with family and social relationships, financial and employment stability, and overall well-being.

Negotiating competing priorities

Participants described symptoms as another challenge to navigate on top of their already burdensome treatment schedule, comorbid medical conditions and other life, family and financial responsibilities. Symptom coping behaviors such as strategically timed naps or restricted eating schedules also added to the burden of negotiating numerous life demands.

Challenging view of self

For many, symptoms served as tangible reminders of eroded self-identities. Many participants took pride in their self-control, mental toughness and ‘positive attitude’, but began to question these self-identities when they felt discouraged by frequent or severe symptoms. Self-identifies also appeared to influence willingness to report symptoms as some patients prided themselves on symptom endurance—‘I can take it’.

Developing adaptive coping strategies

Embracing positive strategies

Patients cited positive symptom coping strategies including optimistic outlooks, self-advocacy and treatment vigilance. Many noted that a positive attitude helped them cope with their machine dependence and feelings of lost control over their medical condition. For many, self-advocacy took the form of proactive symptom reporting and activation in their own medical care.

Adopting negative strategies

Others felt ‘helpless’ in the face of symptoms and reacted negatively with self-defeating behaviors such as deliberate noncompliance with dietary restrictions and/or treatment schedules. Others disengaged and withheld symptoms from their care team, noting that past self-advocacy efforts had not changed their symptom experience.

Modulating behavior

All participants described adapting behavior to prevent or manage dialysis-related symptoms. Some adaptive behaviors included modifications to diets, sleeping patterns and daily activity schedules. Many described making deliberate trade-offs between symptoms and other life commitments. For example, some chose to drink less fluid to avoid shortness of breath at the expense of thirst. Conversely, others deliberately risked shortness of breath to avoid thirst. Many scheduled social activities around post-dialysis naps. Patients strove for symptom balance and tolerability, rather than avoidance. In general, symptom-free hemodialysis was viewed as an unachievable goal. For many, these internal conflicts also influenced symptom reporting. Most described negotiating trade-off decisions on their own, without input from medical providers. Some patients described intentionally not reporting symptoms so they ‘could get as much fluid removed as possible’ and lessen the chance of fluid overload symptoms prior to their next treatment.

Creating a personal symptom narrative

Living in uncertainty

Overall, participants were frustrated by the absence of explanations for their symptoms. In part, they attributed their own poor symptom understanding to their care team’s unsatisfactory level of knowledge about symptoms. Conflicting information from care team members and lack of symptom-directed therapies reinforced this impression. This medical uncertainty often led to anxiety about potential, undiscussed health consequences of their existing symptoms. Lack of concrete explanations for symptoms led many to render symptom reporting futile as prior reports had not yielded improvements in their treatment experiences.

Developing personal beliefs about symptom attribution

In the absence of sound symptom explanations, patients developed their own symptom narratives. Many related their symptoms to aspects of the hemodialysis procedure, namely fluid removal. Other patients blamed themselves, citing poor compliance or overindulgence. Recognizing the non-physiologic nature of dialysis some attributed symptoms to the ‘machine’ itself. When not provided with alternative, acceptable explanations for symptoms by their care teams, many participants stopped seeking explanations altogether and thus ceased proactively reporting symptoms.

Normalizing symptoms

Frequency, perceived pervasiveness and absence of symptom explanations led many patients to normalize symptoms—‘it’s just one of those things with dialysis’. Identifying symptoms to be ‘normal’ appeared to underlie many patients’ tendencies to underreport symptoms.

Negotiating loss of control

Activating fear

Symptoms, in particular heart palpitations, chest pain and dyspnea, brought uncertainty and fear about potential health ramifications.

Surrendering to vulnerability

Many patients found the dialysis treatment both physically and emotionally confining. Patients felt ‘trapped’ and vulnerable to symptoms during treatments but infrequently voiced this feeling to their care teams.

Bearing witness to pivotal moments and deterioration

Some patients described witnessing severe symptoms in neighboring patients. Close proximity to these events influenced and often exacerbated feelings of insecurity and vulnerability, causing increased patient apprehension about their own symptoms. For some, this apprehension seemed to increase reporting out of fear of potential symptom consequences. For others, fear appeared to contribute to underreporting in efforts to avoid confronting symptoms perceived to reflect their own mortality.

Encountering the limits of the dialysis delivery system

Feeling let down by care providers

Many patients expressed frustration with the care environment. Some felt that care providers lacked empathy about symptoms, and others described hurried patient–provider encounters that led to superficial relationships. Lack of trust and meaningful provider engagement appeared to contribute to some individuals’ reticence to report symptoms. Conversely, trusting, supportive relationships cultivated environments where patients felt comfortable reporting their symptoms.

Perceiving that symptom reporting is futile

Some patients cited experiences with symptom reporting that had not resulted in the expected response (i.e. empathetic reaction or targeted treatment). Some felt that clinic personnel dismissed or ignored reported symptoms—‘They don’t do anything about it, so I feel it’s no use in telling.’ Others described reporting symptoms, witnessing documentation of the report and then not receiving adequate follow-up—breeding mistrust and diminishing the likelihood of future reporting.

Blaming the business of dialysis

Many participants expressed frustration with the dialysis care delivery system, blaming lack of staff education and competing professional demands for inadequate symptom treatment. These observations also drove many to underreport their symptoms—either because they did not feel they had opportunity to do so or because they did not feel that staff would respond in a helpful manner. A couple patients attributed their symptoms to standardized dialysis prescriptions, noting that more treatment ‘individualization’ might help.

Exploratory nurse and PCT interview themes and subthemes

In exploratory dialysis nurse and PCT interviews, we identified three themes: searching for symptom explanations, facing the limits of their roles and encountering the limits of the dialysis delivery system (Table 4). Similar to patients, dialysis personnel often attributed symptoms to aspects of the dialysis procedure, most commonly, the speed or volume of fluid removal. Some blamed patients for symptoms, citing dietary indiscretions. A couple of participants questioned the ‘realness’ of symptoms, with one PCT suggesting that cramping ‘is in their head’. Clinic personnel recognized the perplexing variability of symptoms across individuals, reinforcing their impressions that symptoms are poorly understood. Similar to patients, personnel described challenges in balancing symptoms. Most commonly, such challenges related to too much and too little fluid removal. Poor understanding of symptom etiology and inter-patient symptom variability further complicated treatment decision-making. As recognized by patients, dialysis clinic personnel felt that competing professional demands often constrained their abilities to ask about symptoms and promptly address them. In general, personnel were deeply frustrated by this limitation as most expressed a genuine desire to relieve their patients discomfort and felt helpless when they could not. Expressing compassion for his/her patients’ plights, one PCT said: ‘Sitting in that chair for so long. … I tell them, my heart goes out to you because there is no way I could sit in that chair for that long.’

Table 4.

Illustrative clinic personnel quotations for identified exploratory themes and subthemes

| Themes and subthemes | Quotationsa |

|---|---|

| Searching for symptom explanations | |

| Realizing their own poor understanding of symptoms | |

| ‘It’s sometimes hard to gauge. Is this a symptom that you’re having because of your fluid overload or is it just a headache? So it’s kind of hard to pinpoint whether that’s a symptom of fluid or what’s going on there.’ (25 years, male, RN) | |

| ‘So I’m not sure if he’s actually getting a little bit of true weight, and we’re trying to pull too much fluid, and that was causing the cramps, or if he was just like had a lot of sodium in his body, and his body just wouldn’t recover from trying to pull the fluid out.’ (33 years, female, PCT) | |

| Developing personal beliefs about symptom attribution | |

| ‘I want to say probably their blood coming out their body is the [symptom] cause. The blood getting clean. Yes, that’s probably making them feel like that.’ (41 years, female, PCT) | |

| ‘For instance, your Monday and Tuesday treatments they’re the hardest days because they have more fluid on.’ (49 years, female, RN) | |

| ‘I don’t think I have evidence of it, but I would assume the hours they’re prescribed affect symptoms.’ (43 years, male, PCT) | |

| Blaming patients for symptoms | |

| ‘Then you’ve got those with lack of control, which I know it’s hard, but that lack of control. A big problem is folks with noncompliance.’ (48 years, female, RN) | |

| ‘The fact that they don’t pay attention to what they eat the day before or the day of dialysis. They just don’t care. They’ll bring chips in… and those are the people that will tend to cramp because that salt will try to keep the moisture there, or the liquid in, and we’re trying to pull it out, and there’s a conflict there. But somehow that turns back to be our fault according to them.’ (54 years, male, PCT) | |

| ‘This is going to sound really funny, but I think most of the cramping is in their head.’ (23 years, female, PCT) | |

| Recognizing the variability of patient symptom experiences | |

| ‘Everyone is so different. There’s some people that won't feel any different. There’s some people that’ll feel it until the next time. And sometimes you could be completely fine after, and always feel fine after, and then one day you just don’t. It varies. It’s very different.’ (21 years, female, RN) | |

| ‘Some people… they can’t do anything the next day. Some people bounce back within a couple of hours. I’d say every patient is different… everybody handles every treatment differently.’ (54 years, male, PCT) | |

| Facing the limits of their roles | |

| ‘I had him talked into challenging, but I didn’t realize he was taking all these blood pressure pills prior to treatment. So it’s no wonder he’s feeling bad.’ (48 years, female, RN) | |

| ‘I like to give fluid last [to treat cramping] because giving fluid defeats the purpose.’ (43 years, male, PCT) | |

| ‘People come in with short breath if they’re overloaded… but we’ve also noticed that if they get too much off, it’s also hard to breathe.’ (54 years, male, PCT) | |

| Encountering the limits of the dialysis delivery system | |

| Competing professional demands | |

| ‘We try to give the best patient care but a lot of times the scheduling or the regulations that are put into place, they make that difficult. Sometimes there's really not enough staffing to provide those patients care when they're experiencing symptoms. A lot of the times if my patients are cramping or if their blood pressure drops, I'm doing something with another patient that I can't drop to go and address that, so I have to call somebody else to go take care of that. It's difficult having four patients in a bay and if they're all experiencing something different and you have to cater to them differently for all of their needs, it's definitely a difficult task sometimes.’ (20 years, female, PCT) | |

| ‘There are some days that we have no problems throughout the whole day. Then there are some days it seems like everybody is getting a cramp, or their blood pressure drops. Everybody’s got to get hands-on on everybody. So we have good days and crazy days.’ (33 years, female, PCT) | |

| Assuming that most patients report their symptoms | |

| ‘Yeah, they’ll normally tell us… There’s a few patients that will not tell you that they don’t feel good, and then the next thing you know, they are passed out because their blood pressure dropped, and yeah. But, normally, if they start to not feel well, they’ll tell you.’ (21 years, female, RN) | |

| ‘I would say the majority do report their symptoms. [Those who don’t report symptoms] don’t want the fluid. They don’t want you to stop pulling fluid. They want to meet their goal—that’s the ultimate thing.’ (43 years, male, PCT) | |

Quotations are from dialysis clinic personnel participants.

RN, nurse; PCT, patient care technician.

While most patients described underreporting symptoms to staff, clinic personnel felt that most patients generally fully disclosed symptoms. A few recognized that some patients intentionally withheld symptoms to reach their treatment goals, but cited this practice as an exception to the perceived norm of full symptom reporting.

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide a window into the challenges and uncertainties faced by some patients as they endure and balance interconnected dialysis-related symptoms and competing health and life priorities. In addition, they provide explorative insight into staff impressions of the patient symptom experience and potential discrepancies in perceived reporting habits. The reality of life being dependent on a machine deeply colored patient symptom experiences. Some patients responded to this with positive coping strategies while others reacted with negative, often self-defeating behaviors. Uncertainty surrounding symptom etiology left many to create their own symptom narratives and normalize their experiences. Clinic personnel experienced similar frustrations, citing a desire to help with symptoms, but feeling limited by their lack of knowledge and time. Absence of targeted symptom therapies left both patients and staff frustrated with the dialysis delivery system itself. Overall, patient experiences and perceptions appeared to influence symptom-reporting tendencies, leading some to communicate proactively about symptoms, but others to endure silently all but the most severe symptoms.

Participants described substantial life intrusiveness of dialysis-related symptoms and associated coping strategies. This life impact extended far beyond the dialysis treatment itself, markedly affecting social interactions and leisure pursuits, thereby contributing to a restricted lifestyle that, for many, eroded their self-identities over time. These findings echo themes from our group’s prior qualitative analysis of patient perspectives on kidney disease advocacy where participants cited post-dialysis fatigue and other treatment-related symptoms as barriers to advocacy activity participation [11]. These observations are also consistent with sociologist Kathy Charmaz’s research in which she identified a ‘loss of self’ as central to suffering from chronic illness [12]. For many of our interviewees, feelings of lost control, vulnerability and being ignored wore away at their senses of self. For some, this influenced their willingness and ability to actively participate in their own care, including proactively reporting symptoms to their care teams.

Erosion of self-identity as well as frustration with the care system also seemed to influence some participants’ willingness to spontaneously report symptoms. The majority of patients described underreporting their symptoms to their care teams. Many patients expressed a sense of futility around symptom reporting that grew from their observations that: (i) medical providers do not understand symptoms; (ii) there are few symptom-specific therapies; and (iii) past attempts to discuss symptoms had not led to improvement in their dialysis experiences. Specifically, patients cited the hectic clinic environment and numerous competing duties of nurses and PCTs as impediments to symptom reporting. This reality was echoed by clinic personnel who acknowledged feeling constrained by patient load and duties. Importantly, and perhaps not obvious to patients, clinic personnel were deeply frustrated by these limitations and expressed desire to better recognize and respond to patient symptoms. These data suggest that incorporation of symptom assessments into routine clinical processes would not only allow for better symptom recognition, but might also strengthen the connections between patients and care teams.

It is likely that numerous health care environment, patient and symptom factors influence symptom reporting among dialysis patients. In non-dialysis populations, symptom features such as intensity and proximity to report and patient factors such as emotional state, self-esteem and optimism have been shown to influence symptom reporting [13–16]. As such, the frequency at which providers inquire about symptoms may influence the symptoms that patients report. Additionally, we found a discordance between patient and clinic personnel beliefs about symptom reporting. In our exploratory interviews, clinic personnel believed that patients generally do voluntarily communicate about their symptoms. Accordingly, some care team members abstained from probing further about symptoms under the assumption that patients are already spontaneously reporting them in full. This discordance should be addressed in future studies focused on clinic personnel.

Finally, it is notable that our interviewers asked participants to focus their responses on physical symptoms; yet, almost all participants also spoke about mood symptoms, recognizing an interconnection between physical and mood symptoms. For example, feeling ‘washed-out’ after treatments left some unable to participate in social activities, isolating them from support networks and contributing to feelings of sadness and loss. Many participants were unable to fully separate symptom types, suggesting that improvement in physical symptoms may be one strategy to improve mood symptoms. The latter is particularly important given the high prevalence of mood symptoms among individuals on dialysis and their demonstrated associations with poor clinical and patient-reported outcomes [17–19]. It is plausible, then, that standardized assessment of physical symptoms may lead to improvements in both physical and mood symptoms and their associated health consequences.

Together, our findings suggest that it may be beneficial to create opportunities for patients and their care teams to engage about symptoms. Examples could include incorporating standardized symptom reviews into routine nursing assessments, evaluating KDQOL symptom subscale responses or administering symptom checklists or specific symptom questionnaires. Multiple questionnaires such as the Dialysis Symptom Index, Modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, and Palliative Care Outcome Symptom Scale (POS-S Renal) have been used in the dialysis population in research and clinical practice, but, to-date, there has not been widespread uptake of any instrument, particularly in the USA [20]. Interviews conducted by Cox et al. revealed that patients identified dialysis team partnership as key to symptom management [4]. This potential is supported by data from advanced cancer patients demonstrating that clinician review of longitudinal reports of patient-reported symptoms can improve patient quality of life, enhance patient–clinician communication and reduce hospital encounters [5]. Formalized symptom data collection obviates the need for spontaneous reporting, facilitates timely symptom recognition and may improve symptom management. Essential to any symptom reporting process is meaningful patient involvement in associated care planning and timely patient feedback about planned interventions. Most importantly, standardized symptom data collection and subsequent responsive clinical care may improve patients’ dialysis treatment experiences, potentially enabling fulfillment of life goals and improving quality of life.

Our study limitations relate to study transferability to other populations and potential biases. We included only in-center hemodialysis patients. Symptom experiences and reporting tendencies of individuals receiving home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis may differ and warrant dedicated study. Additionally, we excluded non-English-speaking individuals. Data from non-dialysis populations support cultural differences in symptom experiences and reporting [21–24]. Different perspectives may have been captured among individuals of different ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, individuals volunteered to participate in the interview study. Those who chose to participate in this study may differ from those who did not; selection bias may be present. Second, we conducted face-to-face and telephone interviews to increase our geographic range and enhance participant diversity; data capture may have differed by interview approach. Third, we conducted exploratory interviews with dialysis clinic personnel to provide different perspectives and enrich our data. We did not attempt to reach data saturation, and the presented themes are considered exploratory. We included clinic personnel themes to provide additional insights into the patient experience.

In conclusion, the perspectives shared by our participants draw attention to the importance of delving deeper to understand patient symptoms, broadening our knowledge of symptom pathophysiology and seeking better therapeutic strategies. Interrupting symptom cycles may be one approach to improving patients’ treatment experiences and quality of life. However, providers must be aware of and understand symptoms in order to address them. Establishing protocols that encourage symptom reporting and patient–provider engagement over symptoms may represent a path toward achieving this aim.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all study participants for sharing their experiences and perspectives on hemodialysis-related symptoms and symptom reporting. The authors also thank research liaisons, Lisa Johnson and Nino McHedlishvili, who facilitated interviews at the University of Virginia. Finally, the authors thank Paul Mihas from the Odum Institute for Research in Social Science at UNC Chapel Hill for his guidance and insightful comments.

FUNDING

This work was supported by an unrestricted, investigator-initiated research grant from Renal Research Institute (RRI), a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care (FMC), North America. Neither RRI nor FMC played any role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. J.E.F. is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institute of Health Grant K23 DK109401.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and oversight was performed by J.E.F.; analysis of data by J.E.F., A.D. and J.H.N.; and interpretation of data, article drafting and final approval by all authors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

J.E.F. has received investigator-initiated research funding from the RRI, a subsidiary of FMC, North America. In the past 2 years, J.E.F. has received consulting fees from FMC, North America and speaking honoraria from American Renal Associates, American Society of Nephrology, Baxter, National Kidney Foundation and multiple universities. In the past 2 years, D.F. has received speaking honoraria from National Kidney Foundation. E.A-R. has received investigator-initiated research funding from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals as well as research funding from Bayer Pharmaceuticals. In the past 2 years, E.A-R. has received speaking honorarium from International Society for Blood Purification.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD.. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4: 1057–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK. et al. Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2: 960–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Claxton RN, Blackhall L, Weisbord SD. et al. Undertreatment of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 39: 211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cox KJ, Parshall MB, Hernandez SH. et al. Symptoms among patients receiving in-center hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Hemodial Int 2017; 21: 524–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG. et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 557–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Patient-Reported Outcomes Technical Expert Panel Final Report https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/TEP-Current-Panels.html (15 December 2017, date last accessed)

- 7. Funch DP. Predictors and consequences of symptom reporting behaviors in colorectal cancer patients. Med Care 1988; 26: 1000–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J.. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Braun V, Clarke V.. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schober GS, Wenger JB, Lee CC. et al. Dialysis patient perspectives on CKD advocacy: a semistructured interview study. Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 69: 29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 1983; 5: 168–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brodie EE, Niven CA.. Remembering an everyday pain: the role of knowledge and experience in the recall of the quality of dysmenorrhoea. Pain 2000; 84: 89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gedney JJ, Logan H, Baron RS.. Predictors of short-term and long-term memory of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. J Pain 2003; 4: 47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Leupoldt A, Mertz C, Kegat S. et al. The impact of emotions on the sensory and affective dimension of perceived dyspnea. Psychophysiology 2006; 43: 382–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van der Sande FM, Cheriex EC, van Kuijk WH. et al. Effect of dialysate calcium concentrations on intradialytic blood pressure course in cardiac-compromised patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 32: 125–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC. et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int 2013; 84: 179–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boulware LE, Liu Y, Fink NE. et al. Temporal relation among depression symptoms, cardiovascular disease events, and mortality in end-stage renal disease: contribution of reverse causality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1: 496–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lacson E, Li NC, Guerra-Dean S. et al. Depressive symptoms associate with high mortality risk and dialysis withdrawal in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 2921–2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flythe JE, Powell JD, Poulton CJ. et al. Patient-reported outcome instruments for physical symptoms among patients receiving maintenance dialysis: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66: 1033–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lavin R, Park J.. A characterization of pain in racially and ethnically diverse older adults: a review of the literature. J Appl Gerontol 2014; 33: 258–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bagayogo IP, Interian A, Escobar JI.. Transcultural aspects of somatic symptoms in the context of depressive disorders. Adv Psychosom Med 2013; 33: 64–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P. et al. Cultural meanings of pain: a qualitative study of Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med 2008; 22: 350–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mesquita B, Walker R.. Cultural differences in emotions: a context for interpreting emotional experiences. Behav Res Ther 2003; 41: 777–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.