Abstract

Despite all we have learned since 1918 about influenza virus and immunity, available influenza vaccines remain inadequate to control outbreaks of unexpected strains. Universal vaccines not requiring strain matching would be a major improvement. Their composition would be independent of predicting circulating viruses and thus potentially effective against unexpected drift or pandemic strains. This commentary explores progress with candidate universal vaccines based on various target antigens. Candidates include vaccines based on conserved viral proteins such as nucleoprotein and matrix, on the conserved hemagglutinin (HA) stem, and various combinations. Discussion covers the differing evidence for each candidate vaccine demonstrating protection in animals against influenza viruses of widely divergent HA subtypes and groups; durability of protection; routes of administration, including mucosal, providing local immunity; and reduction of transmission. Human trials of some candidate universal vaccines have been completed or are underway. Interestingly, the HA stem, like nucleoprotein and matrix, induces immunity that permits some virus replication and emergence of escape mutants fit enough to cause disease. Vaccination with multiple target antigens will thus have advantages over use of single antigens. Ultimately, a universal vaccine providing long-term protection against all influenza virus strains might contribute to pandemic control and routine vaccination.

Keywords: antibodies, cross-protection, influenza, influenza vaccines, T cells, universal influenza vaccines, vaccines, viral antibodies

The deadly spread of influenza is a risk we all hope to reduce. Current vaccination strategies are inadequate because they induce mainly strain-specific immunity that is ineffective against unexpected strains. Universal influenza vaccines protective against all virus strains would be a great improvement. Work on universal influenza vaccines has been going on for decades; however, there has recently been increased interest in this topic. This commentary includes discussion of cross-protection against influenza virus infection and progress with universal vaccine candidates, specifically breadth and durability of protection in animals, escape mutation in target antigens, findings in human surveillance and challenge studies, and reported clinical trials. The discussion cannot cover all studies, but examples are presented.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

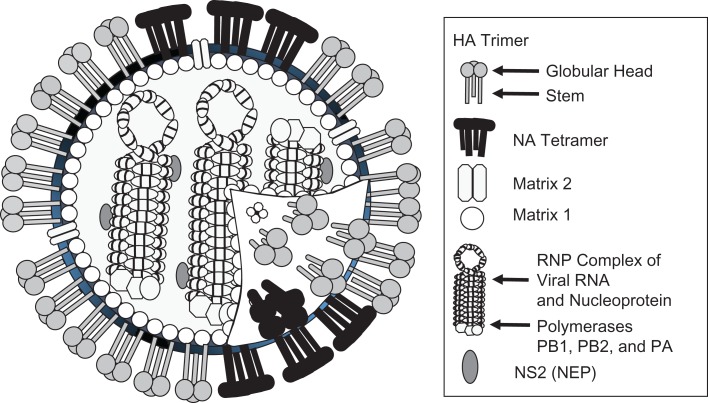

Influenza virus surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (Figure 1), targets of classical strain-matched vaccines, evolve rapidly. Nucleoprotein (NP), matrix 1 (M1) and matrix 2 (M2), polymerases (i.e., PB1, PB2, and acidic polymerase), and the HA stem change more slowly, so vaccines based on these antigens may protect more broadly. Cross-protection against virus of a particular influenza A subtype by immunity to another (i.e., mismatched HA and neuraminidase), for example, protection against H3N2 induced by H1N1, is known as heterosubtypic immunity, and has been studied in animal models since the 1960s (1–3). Cross-protection by wild-type virus was found to be induced by internal viral proteins (4–6). In mechanism studies, cross-protection was shown to be mediated by antibodies and/or T cells, depending upon conditions (7, 8). For the HA stem as target antigen, cross-protection by monoclonal antibody was demonstrated (9).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the influenza virus, indicating major protein components. Hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), nucleoprotein (NP), matrix 1 (M1), and matrix 2 (M2) are the main target antigens proposed for universal vaccines. NEP, nuclear export protein; NS2, nonstructural protein 2; PA, acidic polymerase; RNP, ribonucleoprotein.

Influenza A and B viruses do not generally protect against each other (10, 11) and are more divergent from each other than are influenza A subtypes (12), so vaccines based on one are not expected to protect against both. However, analogous approaches can be applied to influenza B vaccination. Influenza B virus HA is far less diverse than that of influenza A (13). In addition, conserved protein NP, a universal vaccine target, has been estimated to evolve more slowly in influenza B than influenza A (14). Thus, a universal influenza B vaccine, if it induced durable protective immunity, might be useful over a longer period. Some vaccine candidates cover both influenza A and B by including multiple components (15).

STRENGTH AND BREADTH OF PROTECTION BY ACTIVE IMMUNIZATION TO VIRUS PROTEINS

The outcomes described in the following paragraphs were chosen to show the extent of protection that has been achieved by an antigen, though the same antigen may fail to protect under other circumstances. Results are influenced by vectors or adjuvants, administration route (intranasal/mucosal vs. parenteral/systemic), vaccine or challenge virus doses and strains, and responder genetics. Protection experiments should include animals given control constructs with irrelevant antigens, not just buffer, because many vector backbones, production cell components, and matrices have nonspecific or innate immune effects.

Nucleoprotein

NP differs modestly between influenza A strains: There is greater than 90% amino acid identity between H1 and H3 viruses (group 1 vs. group 2) (16), but only 36% identity between influenza A and B (12). Immunization with NP and the resulting T-cell protection have been explored since the 1980s, using protein (17–20), DNA vaccines (21–23), and recombinant vectors (24). In mice and ferrets, NP vaccination prevented death and greatly reduced morbidity after challenge with mismatched strains, including highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (24). Enhanced protection was achieved by various prime-boost combinations (24, 25). NP epitopes shared among divergent viruses are recognized by human T cells, even when using viruses the donors have never encountered, including avian influenza viruses (26–28).

Matrix

M2 has a sequence shared by most human influenza viruses (i.e., H1, H2, H3), whereas M2s from avian influenza viruses, such as H5, are more divergent and less serologically cross-reactive (29). M2 has been extensively studied as a vaccine candidate. In a classic study, a fusion protein of the M2 ectodomain with hepatitis B core protein protected against lethal challenge, with protection transferable by passive antibody (30). An M2 ectodomain construct (31) and vectored M2 expression (32) were later shown to protect mice against challenge. Antibodies and T cells contribute to protection (32). A construct combining swine, human, and avian M2 sequences protected broadly (33), but even a single sequence can cross-protect against viruses with different M2 sequences. Vaccines based on M2 sequences of human influenza viruses protected against avian influenza viruses with differing M2 sequences (32, 34). An M2 conformational epitope may be particularly important; passive antibodies to it protect mice against both H1 and H5, according to research on human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (35).

M1 is not a dominant antigen in mice and is studied only occasionally (36, 37). It is a dominant human T-cell target and vaccine component in human trials, as is discussed later in this article.

Hemagglutinin stem

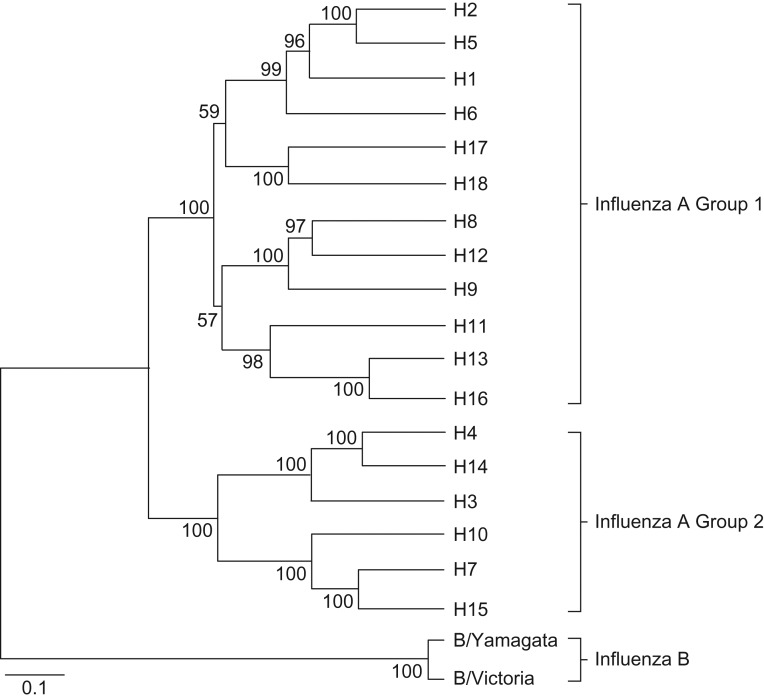

HA has a globular head (HA1 domain) that varies considerably and a more conserved stem (HA2 domain) (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the sequence relationships among HAs, with divergence between group 1 and 2 subtypes, and influenza B lineages. In 1983, polyclonal antibodies to the conserved HA2 region were described (38). In 1993, Okuno et al. (39) discovered mAb C179, recognizing a conserved epitope on multiple HA subtypes. It did not inhibit hemagglutination but had neutralizing activity. The investigators prepared “headless” HA as an immunogen. The headless construct, but not whole HA, protected mice against cross-subtype challenge (H1 vs. H2) (40). Years later, with renewed interest in the HA stem, studies focused on characterizing broadly reactive mAbs (41), and many have now been identified (42). These recognize HAs of group 1 (43), group 2 (44), occasionally both groups 1 and 2 (45, 46), influenza B of both lineages (47), or even both influenza A and B (47).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of hemagglutinin sequences, showing different influenza A virus subtypes in groups 1 and 2, and influenza B lineages, based on amino acid sequences. Reproduced from Figure 1 of Jang et al. (156), available by open access and subject to Creative Commons license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/.

Although rare antibody clones may be useful for passive antibody therapy, vaccines must generate active immunity with protective titers—a more demanding problem. For active immunization to stem epitopes, various constructs have been developed, including engineered stem fragments (48–50), peptides (51), recombinant expression vectors (52), HA-ferritin nanoparticles (53), DNA followed by virus (54), and whole HA, including chimeric constructs (55, 56). There has been some progress with in vivo protection. Some H1-based constructs protected against H5N1, which is highly pathogenic but in the same group 1 (49, 53, 56). Candidates based on H3 or H7 (group 2) protected mice well against matched virus, but only weakly against a different group 2 subtype; they did not protect ferrets (50). Sequential immunization with HA chimeric constructs partially controlled group 1 virus in ferrets (57). An HA-stem trimer construct protected mice partially against viruses in groups 1 and 2 (58). Unless an immunogen efficiently induces antibody to sites shared between groups 1 and 2, a mixture of constructs may be better for optimum protection.

Neuraminidase

Antibodies to neuraminidase can protect against influenza virus infection (59), especially those that inhibit enzymatic activity, so neuraminidase contributes to effectiveness of seasonal vaccines (60). Cross-reactivity (61) and protection (60) extend to mismatched strains within a subtype (62). Neuraminidase virus-like particles (63), but not neuraminidase protein (64), gave some heterosubtypic protection. Discouragingly, with an mAb recognizing all neuraminidase subtypes, an extremely high concentration gave partial protection (65). There are T-cell responses to neuraminidase in animals (66, 67) and humans (27, 68, 69), but their role in protection is unknown. With growing interest in neuraminidase protection, a consortium has proposed extensive research (70).

Polymerases

PB1, PB2, and acidic polymerase are T-cell target antigens in mice (71) and humans (27, 69). PB1 has been investigated as a vaccine antigen (37, 72), but the polymerases are not a major focus.

Combinations of antigens

Since the 1990s, various combinations of antigens have been studied for cross-protection, including vectored NP + M1 (73, 74), HA + NP peptides (75), headless HA + M2 (76), HA + NP + M1 DNA vaccines (77), HA + NP + M2 DNA vaccines (78), and combinations of 5 or 6 antigens (79, 80). The combination NP + M2 provided more powerful protection than either NP or M2 alone and was enhanced by intranasal administration (81, 82). Protection was seen against viruses mismatched for M2 sequence (83), and against H1N1 and H3N2 challenge, preventing morbidity and death 10 months after a single intranasal dose (82). NP + M2 constructs protected against highly pathogenic H5N1 in mice and ferrets (81, 82). Constructs presenting consensus sequences of known epitopes protected broadly against human, avian, and swine challenge viruses, including H9N2 (84). Other proposals have included combining seasonal vaccines with M2 (85) or NP + M1 (86). Combinations often provide protection superior to individual antigens (76, 82, 87), but interference should be considered (88).

Live attenuated influenza vaccines have been considered as universal vaccines. They induce cell-mediated immunity to conserved sites and, in animals, provide some protection against mismatched challenge viruses (83, 89–91). In human studies, T-cell cross-reactivity increases in recipients of live attenuated vaccines (92, 93), with NP a prominent target (93). Clinically, in a drift year, live attenuated vaccine protected against a viral variant not present in the vaccine (94). New types of live attenuated vaccines have been proposed (95, 96). However, for live attenuated vaccines, compared with other conserved vaccine candidates, the dominant antigen of the HA head group may reduce focus of the response on conserved components.

ACTIVE IMMUNIZATION: DURABILITY OF PROTECTION AND RESPONDER AGE

Duration of protection is important for a universal vaccine to cover an outbreak or pandemic wave and ideally would permit less frequent vaccination. For HA stem vaccine candidates, protection of mice or ferrets against challenge was demonstrated 3–4 weeks after a boost (52, 58, 76). For vectored NP + M2 vaccination, a single intranasal dose protected mice for at least 10 months (82), and memory from priming can persist for 16 months (97).

An additional concern is protection of the young and the elderly. HA stem vaccination protected mice 6–8 weeks old (52, 58, 76). Vectored NP + M2 vaccination protected mice 2–20 months old (97). Recent interest in imprinting highlights the importance of birth year in susceptibility to influenza (98). Because imprinting appears related to HA group/subtype (not conserved sites in NP/M or HA stem), it likely would not restrict effectiveness of universal vaccines in different age groups.

STERILIZING IMMUNITY VERSUS INFECTION-PERMISSIVE IMMUNITY

If vaccination induces high-titered neutralizing antibodies to the HA globular head, viral entry is blocked. If immunity is instead mediated by other mechanisms, such as T cells or nonneutralizing antibodies, then transient infection is permitted, but rapid clearance avoids severe disease. Some investigators have considered infection-permissive immunity inadequate, stating, for example, that pandemic spread in the presence of cross-reactive T-cell immunity demonstrates that protection is by antibody (99). The reality is more complex. Individuals differ greatly in their extent of preexisting T-cell immunity, and during a pandemic not all individuals become ill. Assessing whether preexisting T-cell immunity controls infection requires surveillance studies linking individual preexposure T-cell responses with individual monitoring for infection and severity. A pandemic might have been worse without this prior immunity.

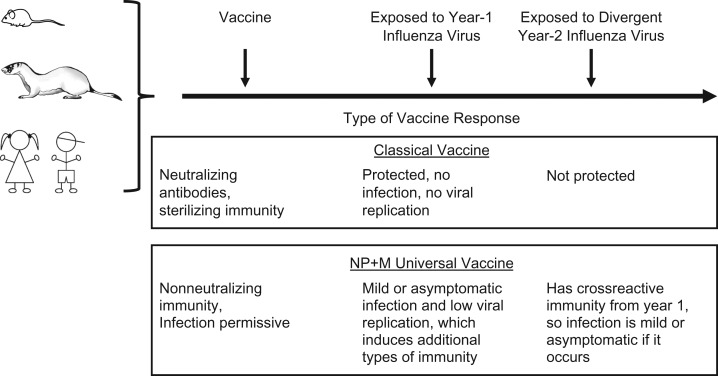

Other investigators have suggested possible advantages of mild infection and debated this as an argument against annual vaccination (100, 101). Cellular immunity to conserved antigens is induced in a host who experiences infection, even asymptomatic or mild infection, and this immunity can control divergent virus encountered later (102). If a vaccine prevents symptomatic disease but not all viral entry or replication, that may be sufficient to protect the recipient while permitting development of additional immune responses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of sterilizing immunity with infection-permissive immunity. The diagram depicts the differing consequences of types of vaccination. Upper box: Classical vaccine induces antibodies that neutralize virus, preventing infection by a matched virus strain. Lower box: Nucleoprotein plus matrix (NP + M) universal vaccine induces nonneutralizing immune responses that partially control infection and reduce the severity of disease, but allow some degree of viral replication. The consequences can differ in a subsequent year when a new viral strain is encountered.

Many universal vaccine candidates do not induce sterilizing immunity. Antibodies to NP are nonneutralizing, but they passively transfer protection in animals (103), which involves Fc receptors (104). Antibodies to M2 also passively transfer protection (32), which can depend on Fc-receptor mechanisms (105) and natural killer cells (106).

Similarly, antibodies to HA can protect by multiple mechanisms and do not always confer sterilizing immunity. Human sera have antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activity reactive with influenza viruses (107–109). This activity was associated with protection in some reports (110) but not in others (111). Some antibodies to the HA stem neutralize in vitro, but Fc receptor–dependent mechanisms are required in vivo (112, 113). Antibody to the HA stem that does not neutralize in vitro can protect animals (114). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay binding has been suggested as a correlate for protection, based on passive transfer of human antibodies to mice (115). Many questions remain regarding mechanisms of protection by stem-reactive antibodies. In any case, although HA stem immunity includes some neutralizing antibodies, viral titer results show that available candidate vaccines are operationally infection permissive, including one protective against both group 1 and 2 challenge (58).

The fact that NP and M vaccines do not induce sterilizing immunity was often viewed as a drawback compared with HA-based vaccines. Ironically, not only may that property sometimes be an advantage rather than a drawback, but it also turns out to be a property of many HA stem vaccines.

SELECTIVE PRESSURE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY OF ESCAPE MUTANTS

For NP, naturally occurring infection induces strong antibody and T-cell responses. The relative conservation of NP sequence may be due to structural constraints and to the fact that anti-NP immunity is infection permissive. However, there is selective pressure and escape mutants are detected (8, 116–118). Sequences of viruses from a human outbreak revealed emergence of new NP mutations in cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes, consistent with evasion of T-cell immunity that otherwise helped contain the virus (116). These mutations spread through the population (116, 119). Using a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope as a probe, variants were shown to emerge in an order suggesting immune selection (117). Mutations in dominant T-cell epitopes also emerged in infected mice but reverted in the absence of selective pressure, suggesting a fitness cost (118).

Mutation in an epitope does not necessarily mean lack of immune recognition for the whole protein and overall escape. The 2009 pandemic virus had a different NP418–426 sequence than previously circulating viruses, and that peptide was not recognized by prepandemic human T cells (120). However, a pool of pandemic sequence NP peptides restimulated T-cell responses in prepandemic samples from 97% of normal human donors (69), presumably due to recognition of other epitopes.

For M2, the limited naturally occurring sequence variation could be due to structural constraints, but in addition, infection induces only weak immune responses to M2 and thus little selective pressure. Strong selective pressure was tested to see if it would reveal greater variation. Escape mutants emerged in infected mice with severe combined immunodeficiency that were given anti-M2 mAbs. However, only 2 different mutations emerged, suggesting most positions were constrained (121).

Infection generates some HA stem–specific antibodies (41, 122), but selective pressure on the stem likely has been modest in the past. Some investigators hoped the HA stem could not mutate because of structural constraints (8, 123), so an immune response to it would not select escape mutants and an HA stem vaccine would remain effective indefinitely. However, escape mutants were isolated in the original study of broadly reactive mAb C179 (39). Although some later attempts to isolate stem escape variants were unsuccessful (55), others have demonstrated in vitro selection and propagation of viral variants resistant to neutralization by antistem antibodies (123), including broadly neutralizing antibody (114). Multiple mechanisms of escape from neutralization by stem antibodies have been demonstrated (124).

Another hope was that HA stem mutations would carry a high viral fitness cost, reducing replication and ability to cause disease even if detectable in vitro. However, mutations at a site recognized by a broadly neutralizing antibody have been found in H7 viruses from recent human outbreaks (125). In another study (126), analysis of HA sequences of circulating H1N1 viruses since 1918 suggested that immune pressure contributed to the emergence of HA stem variants. The investigators then selected HA stem escape mutants by virus passage in vitro in the presence of polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies. Some stem mutants selected that were less sensitive to neutralization by the antibodies still replicated well in vivo and still caused morbidity and death in mice.

EPITOPE-BASED VACCINES

Escape mutation is a drawback of vaccines based on minimal epitopes and peptides rather than whole proteins. A peptide vaccine providing an immunodominant epitope may not protect against a virus mutated at that site. Another drawback of the approach is that multiple peptides would likely be required to provide epitopes for coverage of diverse human responders. In contrast, use of entire proteins as antigens can enhance population coverage by providing different T-cell epitopes restricted by different human leukocyte antigen alleles, even rare ones. Immunity to entire proteins can also provide some protection against a virus mutated in an immunodominant epitope, by providing recall responses to other epitopes, though compensation can be complex (127, 128).

ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION AND MUCOSAL IMMUNITY

Mucosal immunization in the respiratory tract can provide better protection against influenza virus infection than systemic immunization—up to several million-fold better, as shown in 1950 (10). Universal vaccine candidates have often been given intramuscularly; mucosal administration has been explored subsequently. Intranasal administration of NP and M vaccine candidates proved superior to intramuscular administration (81, 82, 129), with primed immune effectors located at the site of infection (81, 82). NP and M candidates given intranasally have sometimes been given with adjuvant (130). HA stem vaccine candidates given intramuscularly can protect against infection (53, 58), but the intranasal route was superior for a chimeric HA (52).

TRANSMISSION

Strain-matched vaccines inducing neutralizing antibody prevent infection and thus transmission. Universal vaccines based on other mechanisms of protection permit some infection and thus might allow transmission. Some investigators have worried that use of an infection-permissive vaccine would allow continued spread of virus in the population. However, mathematical modeling provided a more optimistic estimate. Based on data from work in ferrets indicating an infection-permissive vaccine reduced virus shedding (81), a mathematical model projected that reduced transmission could limit the size of outbreaks or pandemics and slow virus drift (131). At the time of that work, linkage of reduced virus shedding to reduced transmission was just an assumption. It has now been demonstrated. In a proof-of-concept mouse transmission model, for mice vaccinated with NP + M2 and then infected, transmission to naïve contacts was reduced (132).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HUMAN PROTECTIVE IMMUNITY AND CONTEMPORARY HUMAN STUDIES

Evidence has accumulated, some suggestive and some more definite, that immunity due to previous influenza exposures can protect humans against a novel strain despite absence of neutralizing antibodies to it (133–135). Because of prior infections, humans have readily detectable immune memory responses to conserved influenza virus antigens, including T-cell responses to NP, M1, PB1, and other antigens (26, 27, 136, 137); and antibodies to M2 (69, 138), NP (69), and the HA stem (61, 139). The classic McMichael et al. (140) study pointed to a role of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte immunity in protection, with a reduction in influenza challenge virus shedding but not symptoms. Additional evidence for protection by T cells has been collected recently from surveillance during the 2009 pandemic (68, 141) and from challenge studies (142).

Human challenge studies with live influenza virus were standard practice years ago, continued in some parts of the world, and recently have been undertaken more broadly. Carefully characterized challenge stocks are used in volunteers to study parameters, including transmission, antibody and T-cell responses, cytokines, and correlations between immune parameters and clinical outcomes. In a recent study of antibodies, high preexisting anti-HA stem titers were associated with reduced virus shedding but not reduced symptoms. Neuraminidase-inhibiting antibody titer correlated with reduced symptom severity (139).

Various candidate universal vaccines, including epitope-based vaccines (143–145) and viral vectors expressing NP + M1 (146–150), have been tested in clinical trials. Table 1 summarizes some results. In 1 study, MVA−NP + M1 vaccination induced T-cell responses, and vaccinees had reduced symptoms and duration of viral shedding compared with controls (146). Safety and efficacy of MVA−NP + M1 given with inactivated vaccine are being tested in a phase IIb study (86). A phase III study is in progress of a protein containing 9 conserved epitopes (HA, NP, M1; influenza A and B) (151). Clinical experience with HA stem vaccines is beginning. A DNA vaccine expressing whole HA induced antibody to the HA stem in humans (152), and a trial of live attenuated and inactivated viruses with chimeric HAs is beginning (153). Regarding immune correlates, it was reported in 1 trial that cellular immunity (detected by interferon-γ enzyme-linked immunospot assay) correlated with reduced viral shedding and symptoms (144).

Table 1.

Examplesa of Universal Vaccine Candidates in Clinical Trials and Studies

| Vaccine/Route | Population and Age, years | Immune Responses, and Protection Outcomes, if Tested | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biondvaxb M-001, recombinant protein containing 9 B- and T-cell conserved epitopes of HA, NP, and M1, of influenza A and B, or placebo, intramuscular, followed by TIV | Adults 18–45 | M-001 alone induced CD4 and CD8 responses to influenza antigens. M-001 followed by TIV primed for enhanced seroconversion (HI), even to strains not in the TIV. | 15 |

| Biondvax intramuscular followed by suboptimal dose of H5N1 investigational vaccine | Adults 18–60 (phase IIb) | Antibody and cellular response endpoints. Completed according to ClinicalTrials.gov, but results not yet public. | 143 |

| Biondvax intramuscular (A Pivotal Trial to Assess the Safety and Clinical Efficacy of the M-001 as a Standalone Universal Flu Vaccine) | Adults >50 (phase III) | PCR-positive influenza (% confirmed cases, vaccine vs. placebo), frequency of IFN-γ restimulated CD4 T cells. Estimated data collection completion according to ClinicalTrials.gov: May 2020. | 151 |

| Mixture of M1, NPA, NPB, and M2, peptides (20–32-mers) vs. placebo, with ISA-51 adjuvant, subcutaneous, followed by challenge | Men 18–45 | Cellular responses; postchallenge viral titers and symptoms. IFN-γ response to stimulation with vaccine correlated with reduced viral shedding and symptoms after challenge. | 144 |

| 6 modified 35-mer peptides of NP, M, PB1, and PB2, intramuscular, vs. placebo | Adults 22–55 | Increases in CD4 and CD8 IFN-γ responses, with recognition of multiple viral strains | 145 |

| Mixture of H5, NP, and M2 DNA given twice intramuscular, compared with H5 DNA alone | Adults 18–45 | Antibody responses (HI, MN, and ELISA antibody to M2e), NP, M2, and H5 T-cell IFN-γ responses. Subset of subjects responded, more often T-cell response to NP or H5 T cells than the other responses. | 157 |

| H5 DNA vaccine intramuscular followed by monovalent inactivated H5N1 (not a universal vaccine, study included here only because of testing of responses to HA stem) | Adults 18–60 | Antibody to H5 by multiple methods, CD4 intracellular cytokine responses to H5. Antibody to HA stem tested for 1 subject per group; some activity detected. | 152 |

| LAIV intranasal, and trivalent inactivated vaccine intramuscular, in prime-boost sequences | Healthy children | HI antibodies induced in all groups. CD4+, CD8+, and γδ T-cell IFN-γ responses to live virus or M1/M2 and NP peptide pools increased in groups receiving LAIV, not groups with TIV only. Cellular responses were not correlated with HI. | 158 |

| Chimeric cH8/1N1 LAIV or chimeric cH8/1N1 IIV or placebo, followed 3 months later by chimeric cH5/1N1 IIV. AS03 adjuvant in some groups. | Adults 18–39 | Will measure immune responses. Active according to ClinicalTrials.gov, but not yet recruiting. | 153 |

| MVA−NP + M1, intramuscular, followed by influenza challenge vs. challenge in unvaccinated controls | Adults 18–45 | Vaccination induced T-cell IFN-γ responses to NP + M1. Compared with control subjects, vaccinees had reduced symptoms and duration of viral shedding. | 146 |

| MVA-NP + M1, intramuscular | Adults >50 | CD4 and CD8 T-cell IFN-γ responses to NP + M1 increase with vaccination. Magnitude and duration depend on responder age. | 147 |

| ChAdOx1 NP + M1 intramuscular ± MVA−NP + M1 intramuscular boost | Adults 18–50 | Cellular IFN-γ responses to NP + M1 peptide pools increase after single ChAdOx1 vaccination. | 148 |

| MVA−NP + M1, intradermal or intramuscular | Adults 18–50 | Cellular IFN-γ responses to NP + M1 peptide pools increase after vaccination. Majority are CD8 T cells, fewer are CD4. IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, and CD107a multifunctional cells also increase. | 149 |

| MVA−NP + M1 plus TIV vs. TIV plus placebo, all intramuscular | Adults >50 | T-cell IFN-γ responses to NP + M1 peptide pools were greater for MVA-NP + M1 plus TIV than for TIV alone. ELISA antibody to TIV antigens was slightly, though not significantly, higher for the group given MVA-NP + M1 plus TIV (adjuvant-like effect) than TIV alone. | 150 |

| MVA−NP + M1 plus TIV vs. TIV plus placebo, all intramuscular | Adults ≥65 (phase IIb) | Plan: Surveillance of 2030 subjects for influenza symptoms, severity, and duration of infection. Immunology substudy (n = 50 per group): antibody and T-cell responses. Currently in progress, results not available. | 86 |

Abbreviations: CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; CD8, cluster of differentiation 8; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HA, hemagglutinin; HI, hemagglutination inhibition; IFN, interferon; i.m., intramuscular; LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; M1, matrix 1; M2, matrix 2; MN, microneutralization; MVA, modified vaccinia Ankara; NP, nucleoprotein; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TIV, trivalent inactivated vaccine.

a For a more complete list, see World Health Organization tables on clinical evaluation of influenza vaccines (159). The webpage includes vaccines other than universal candidates, but a linked table (160) includes broadly protective strategies.

b BiondVax Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Ness Ziona, Israel.

THE PATH FORWARD

Vaccine protection need not be perfect, and achieving a proposed goal of 75% or greater protection against symptomatic disease (154) would be a desirable outcome. Even short of that, a major reduction in severity would be valuable, as would a reduction in transmission. Enthusiasm for HA stem vaccines is prompted by discovery of potent and broadly neutralizing HA stem antibodies. NP + M vaccines are further along in demonstrating various parameters of effectiveness in animals (i.e., breadth, duration, range of recipients tested, reduction in transmission) and immunogenicity in humans. Vaccines based on all these antigens should be pursued, with further characterization for potency, breadth and duration of protection in animals, immune responses, and correlates of protection. We need to understand how each vaccine works, because the immune correlates of protection will not be the same for all components in a combination.

Different universal vaccine candidates can then be combined. NP and M1 are usually expressed from vectors to achieve endogenous expression optimal for inducing T cell immunity, while M2, the HA stem, and neuraminidase can be given as protein or vectored. Some formats (expression vectors, virus-like particles) may be amenable to all these antigens. Ultimately, a combination of NP, M1 and/or M2, HA stem and neuraminidase may be advantageous, but only after optimizing each component and checking for interference in the mixture.

There are many vaccine candidates and limited resources for clinical trials; thus, prescreening may be useful. The scientific community could share materials and conduct simultaneous testing (“tournaments”) comparing routes of administration and vaccine components for potency, breadth and duration of protection in animals, as well as immune response markers. A strategic plan of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for universal influenza vaccine work calls for a consortium (155), which could perhaps coordinate such comparisons.

We have learned a great deal since 1918, but the 2018 influenza season provides a harsh reminder of the serious public health problem we still face with influenza. Research on universal vaccines has made encouraging progress, and these vaccines could contribute to reducing the future toll.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliation: Division of Cellular and Gene Therapies, Office of Tissues and Advanced Therapies, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland (Suzanne L. Epstein).

This work was supported by intramural funds from the US Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Division of Cellular and Gene Therapies.

The author thanks Dr. Graeme Price, US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, for a diagram of influenza virus that was modified to generate Figure 1, and to Chia-Yun Lo for assistance with phylogenetic data.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Abbreviations

- HA

hemagglutinin

- M1

matrix 1

- M2

matrix 2

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NP

nucleoprotein

REFERENCES

- 1. Schulman JL, Kilbourne ED. Induction of partial specific heterotypic immunity in mice by a single infection with influenza A virus. J Bacteriol. 1965;89:170–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yetter RA, Lehrer S, Ramphal R, et al. Outcome of influenza infection: effect of site of initial infection and heterotypic immunity. Infect Immun. 1980;29(2):654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yetter RA, Barber WH, Small PA Jr.. Heterotypic immunity to influenza in ferrets. Infect Immun. 1980;29(2):650–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kees U, Krammer PH. Most influenza A virus-specific memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes react with antigenic epitopes associated with internal virus determinants. J Exp Med. 1984;159(2):365–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Townsend AR, Skehel JJ. The influenza-A virus nucleoprotein gene controls the induction of both subtype specific and cross-reactive cytotoxic T-cells. J Exp Med. 1984;160(2):552–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gotch F, McMichael A, Smith G, et al. Identification of viral molecules recognized by influenza-specific human cytotoxic lymphocytes-T. J Exp Med. 1987;165(2):408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Epstein SL, Price GE. Cross-protective immunity to influenza A viruses. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9(11):1325–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quiñones-Parra S, Loh L, Brown LE, et al. Universal immunity to influenza must outwit immune evasion. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okuno Y, Matsumoto K, Isegawa Y, et al. Protection against the mouse-adapted A/FM/1/47 strain of influenza A virus in mice by a monoclonal antibody with cross-neutralizing activity among H1 and H2 strains. J Virol. 1994;68(1):517–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fazekas de St. Groth S, Donnelley M. Studies in experimental immunology of influenza. IV. The protective value of active immunization. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1950;28(1):61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liang S, Mozdzanowska K, Palladino G, et al. Heterosubtypic immunity to influenza type A virus in mice: effector mechanisms and their longevity. J Immunol. 1994;152(4):1653–1661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Terajima M, Babon JA, Co MD, et al. Cross-reactive human B cell and T cell epitopes between influenza A and B viruses. Virol J. 2013;10:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tan J, Asthagiri Arunkumar G, Krammer F. Universal influenza virus vaccines and therapeutics: where do we stand with influenza B virus? Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;53:45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lindstrom SE, Hiromoto Y, Nishimura H, et al. Comparative analysis of evolutionary mechanisms of the hemagglutinin and three internal protein genes of influenza B virus: multiple cocirculating lineages and frequent reassortment of the NP, M, and NS genes. J Virol. 1999;73(5):4413–4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Atsmon J, Caraco Y, Ziv-Sefer S, et al. Priming by a novel universal influenza vaccine (Multimeric-001)-a gateway for improving immune response in the elderly population. Vaccine. 2014;32(44):5816–5823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Altmüller A, Fitch WM, Scholtissek C. Biological and genetic evolution of the nucleoprotein gene of human influenza A viruses. J Gen Virol. 1989;70(Pt 8):2111–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tite JP, Hughes-Jenkins C, O’Callaghan D, et al. Anti-viral immunity induced by recombinant nucleoprotein of influenza A virus. II. Protection from influenza infection and mechanism of protection. Immunology. 1990;71(2):202–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wraith DC, Vessey AE, Askonas BA. Purified influenza virus nucleoprotein protects mice from lethal infection. J Gen Virol. 1987;68(Pt 2):433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrew ME, Coupar BE. Efficacy of influenza haemagglutinin and nucleoprotein as protective antigens against influenza virus infection in mice. Scand J Immunol. 1988;28(1):81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jelinek I, Leonard JN, Price GE, et al. TLR3-specific double-stranded RNA oligonucleotide adjuvants induce dendritic cell cross-presentation, CTL responses, and antiviral protection. J Immunol. 2011;186(4):2422–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rhodes GH, Dwarki VJ, Abai AM, et al. Injection of expression vectors containing viral genes induces cellular, humoral, and protective immunity In: Chanock RM, Brown F, Ginsberg HS, et al., eds. Vaccines 93. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ulmer JB, Donnelly JJ, Parker SE, et al. Heterologous protection against influenza by injection of DNA encoding a viral protein. Science. 1993;259(5102):1745–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Epstein SL, Tumpey TM, Misplon JA, et al. DNA vaccine expressing conserved influenza virus proteins protective against H5N1 challenge infection in mice. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(8):796–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Epstein SL, Kong WP, Misplon JA, et al. Protection against multiple influenza A subtypes by vaccination with highly conserved nucleoprotein. Vaccine. 2005;23(46–47):5404–5410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dégano P, Schneider J, Hannan CM, et al. Gene gun intradermal DNA immunization followed by boosting with modified vaccinia virus Ankara: enhanced CD8+ T cell immunogenicity and protective efficacy in the influenza and malaria models. Vaccine. 1999;18(7–8):623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jameson J, Cruz J, Terajima M, et al. Human CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte memory to influenza A viruses of swine and avian species. J Immunol. 1999;162(12):7578–7583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee LY, Ha DLA, Simmons C, et al. Memory T cells established by seasonal human influenza A infection cross-react with avian influenza A (H5N1) in healthy individuals. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(10):3478–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Quiñones-Parra S, Grant E, Loh L, et al. Preexisting CD8+ T-cell immunity to the H7N9 influenza A virus varies across ethnicities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(3):1049–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fan J, Liang X, Horton MS, et al. Preclinical study of influenza virus A M2 peptide conjugate vaccines in mice, ferrets, and rhesus monkeys. Vaccine. 2004;22(23–24):2993–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neirynck S, Deroo T, Saelens X, et al. A universal influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of the M2 protein. Nat Med. 1999;5(10):1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Filette M, Martens W, Roose K, et al. An influenza A vaccine based on tetrameric ectodomain of matrix protein 2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(17):11382–11387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tompkins SM, Zhao ZS, Lo CY, et al. Matrix protein 2 vaccination and protection against influenza viruses, including subtype H5N1. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(3):426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim MC, Song JM, O E, et al. Virus-like particles containing multiple M2 extracellular domains confer improved cross-protection against various subtypes of influenza virus. Mol Ther. 2013;21(2):485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ernst WA, Kim HJ, Tumpey TM, et al. Protection against H1, H5, H6 and H9 influenza A infection with liposomal matrix 2 epitope vaccines. Vaccine. 2006;24(24):5158–5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grandea AG III, Olsen OA, Cox TC, et al. Human antibodies reveal a protective epitope that is highly conserved among human and nonhuman influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(28):12658–12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sui Z, Chen Q, Fang F, et al. Cross-protection against influenza virus infection by intranasal administration of M1-based vaccine with chitosan as an adjuvant. Vaccine. 2010;28(48):7690–7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang W, Li R, Deng Y, et al. Protective efficacy of the conserved NP, PB1, and M1 proteins as immunogens in DNA- and vaccinia virus-based universal influenza A virus vaccines in mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22(6):618–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Graves PN, Schulman JL, Young JF, et al. Preparation of influenza virus subviral particles lacking the HA1 subunit of hemagglutinin: unmasking of cross-reactive HA2 determinants. Virology. 1983;126(1):106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, et al. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza A virus H1 and H2 strains. J Virol. 1993;67(5):2552–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sagawa H, Ohshima A, Kato I, et al. The immunological activity of a deletion mutant of influenza virus haemagglutinin lacking the globular region. J Gen Virol. 1996;77(Pt 7):1483–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Corti D, Suguitan AL Jr., Pinna D, et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing antibodies are produced by individuals immunized with a seasonal influenza vaccine. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(5):1663–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ekiert DC, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against influenza virus and prospects for universal therapies. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2(2):134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, et al. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science. 2009;324(5924):246–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ekiert DC, Friesen RH, Bhabha G, et al. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science. 2011;333(6044):843–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lang S, Xie J, Zhu X, et al. Antibody 27F3 broadly targets influenza A group 1 and 2 hemagglutinins through a further variation in VH1-69 antibody orientation on the HA stem. Cell Rep. 2017;20(12):2935–2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kallewaard NL, Corti D, Collins PJ, et al. Structure and function analysis of an antibody recognizing all influenza A subtypes. Cell. 2016;166(3):596–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dreyfus C, Laursen NS, Kwaks T, et al. Highly conserved protective epitopes on influenza B viruses. Science. 2012;337(6100):1343–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Steel J, Lowen AC, Wang TT, et al. Influenza virus vaccine based on the conserved hemagglutinin stalk domain. MBio. 2010;1(1):e00018-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Impagliazzo A, Milder F, Kuipers H, et al. A stable trimeric influenza hemagglutinin stem as a broadly protective immunogen. Science. 2015;349(6254):1301–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sutton TC, Chakraborty S, Mallajosyula VVA, et al. Protective efficacy of influenza group 2 hemagglutinin stem-fragment immunogen vaccines. NPJ Vaccines. 2017;2:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang TT, Tan GS, Hai R, et al. Vaccination with a synthetic peptide from the influenza virus hemagglutinin provides protection against distinct viral subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(44):18979–18984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ryder AB, Nachbagauer R, Buonocore L, et al. Vaccination with vesicular stomatitis virus-vectored chimeric hemagglutinins protects mice against divergent influenza virus challenge strains. J Virol. 2016;90(5):2544–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yassine HM, Boyington JC, McTamney PM, et al. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat Med. 2015;21(9):1065–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wei CJ, Yassine HM, McTamney PM, et al. Elicitation of broadly neutralizing influenza antibodies in animals with previous influenza exposure. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(147):147ra14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang TT, Tan GS, Hai R, et al. Broadly protective monoclonal antibodies against H3 influenza viruses following sequential immunization with different hemagglutinins. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(2):e1000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, et al. Chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus vaccine constructs elicit broadly protective stalk-specific antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87(12):6542–6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Krammer F, Hai R, Yondola M, et al. Assessment of influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based immunity in ferrets. J Virol. 2014;88(6):3432–3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Valkenburg SA, Mallajosyula VV, Li OT, et al. Stalking influenza by vaccination with pre-fusion headless HA mini-stem. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schulman JL, Khakpour M, Kilbourne ED. Protective effects of specific immunity to viral neuraminidase on influenza virus infection of mice. J Virol. 1968;2(8):778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Eichelberger MC, Wan H. Influenza neuraminidase as a vaccine antigen. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;386:275–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nachbagauer R, Choi A, Hirsh A, et al. Defining the antibody cross-reactome directed against the influenza virus surface glycoproteins. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(4):464–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wan H, Gao J, Xu K, et al. Molecular basis for broad neuraminidase immunity: conserved epitopes in seasonal and pandemic H1N1 as well as H5N1 influenza viruses. J Virol. 2013;87(16):9290–9300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Quan FS, Kim MC, Lee BJ, et al. Influenza M1 VLPs containing neuraminidase induce heterosubtypic cross-protection. Virology. 2012;430(2):127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wohlbold TJ, Nachbagauer R, Xu H, et al. Vaccination with adjuvanted recombinant neuraminidase induces broad heterologous, but not heterosubtypic, cross-protection against influenza virus infection in mice. MBio. 2015;6(2):e02556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Doyle TM, Hashem AM, Li C, et al. Universal anti-neuraminidase antibody inhibiting all influenza A subtypes. Antiviral Res. 2013;100(2):567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hurwitz JL, Hackett CJ, McAndrew EC, et al. Murine TH response to influenza-virus: recognition of hemagglutinin, neuraminidase, matrix, and nucleoproteins. J Immunol. 1985;134(3):1994–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hackett CJ, Horowitz D, Wysocka M, et al. Immunogenic peptides of influenza virus subtype N1 neuraminidase identify a T-cell determinant used in class II major histocompatibility complex-restricted responses to infectious virus. J Virol. 1991;65(2):672–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hayward AC, Wang L, Goonetilleke N, et al. Natural T cell-mediated protection against seasonal and pandemic influenza. Results of the Flu Watch cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(12):1422–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lo CY, Strobl SL, Dunham K, et al. Surveillance study of influenza occurrence and immunity in a Wisconsin cohort during the 2009 pandemic. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(2):ofx023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Krammer F, Fouchier RAM, Eichelberger MC, et al. NAction! How can neuraminidase-based immunity contribute to better influenza virus vaccines? MBio. 2018;9(2):e02332–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Murine cytotoxic T lymphocyte recognition of individual influenza virus proteins. High frequency of nonresponder MHC class I alleles. J Exp Med. 1988;168(5):1935–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Košík I, Krejnusová I, Práznovská M, et al. A DNA vaccine expressing PB1 protein of influenza A virus protects mice against virus infection. Arch Virol. 2012;157(5):811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lambe T, Carey JB, Li Y, et al. Immunity against heterosubtypic influenza virus induced by adenovirus and MVA expressing nucleoprotein and matrix protein-1. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vitelli A, Quirion MR, Lo CY, et al. Vaccination to conserved influenza antigens in mice using a novel Simian adenovirus vector, PanAd3, derived from the bonobo Pan paniscus. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e55435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jeon SH, Ben Yedidia T, Arnon R. Intranasal immunization with synthetic recombinant vaccine containing multiple epitopes of influenza virus. Vaccine. 2002;20(21–22):2772–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Deng L, Mohan T, Chang TZ, et al. Double-layered protein nanoparticles induce broad protection against divergent influenza A viruses. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Donnelly JJ, Friedman A, Martinez D, et al. Preclinical efficacy of a prototype DNA vaccine: enhanced protection against antigenic drift in influenza virus. Nat Med. 1995;1(6):583–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Koday MT, Leonard JA, Munson P, et al. Multigenic DNA vaccine induces protective cross-reactive T cell responses against heterologous influenza virus in nonhuman primates. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Poon LL, Leung YH, Nicholls JM, et al. Vaccinia virus-based multivalent H5N1 avian influenza vaccines adjuvanted with IL-15 confer sterile cross-clade protection in mice. J Immunol. 2009;182(5):3063–3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Karlsson I, Borggren M, Rosenstierne MW, et al. Protective effect of a polyvalent influenza DNA vaccine in pigs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2018;195:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Price GE, Soboleski MR, Lo CY, et al. Vaccination focusing immunity on conserved antigens protects mice and ferrets against virulent H1N1 and H5N1 influenza A viruses. Vaccine. 2009;27(47):6512–6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Price GE, Soboleski MR, Lo CY, et al. Single-dose mucosal immunization with a candidate universal influenza vaccine provides rapid protection from virulent H5N1, H3N2 and H1N1 viruses. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Soboleski MR, Gabbard JD, Price GE, et al. Cold-adapted influenza and recombinant adenovirus vaccines induce cross-protective immunity against pH1N1 challenge in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tutykhina I, Esmagambetov I, Bagaev A, et al. Vaccination potential of B and T epitope-enriched NP and M2 against influenza A viruses from different clades and hosts. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Song JM, Van Rooijen N, Bozja J, et al. Vaccination inducing broad and improved cross protection against multiple subtypes of influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(2):757–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Vaccitech Improved Novel Vaccine Combination Influenza Study (INVICTUS). 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03300362. Accessed March 14, 2018.

- 87. Lo CY, Wu Z, Misplon JA, et al. Comparison of vaccines for induction of heterosubtypic immunity to influenza A virus: cold-adapted vaccine versus DNA prime-adenovirus boost strategies. Vaccine. 2008;26(17):2062–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Patel A, Gray M, Li Y, et al. Co-administration of certain DNA vaccine combinations expressing different H5N1 influenza virus antigens can be beneficial or detrimental to immune protection. Vaccine. 2012;30(3):626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tannock GA, Paul JA. Homotypic and heterotypic immunity of influenza A viruses induced by recombinants of the cold-adapted master strain A/Ann arbor/6/60-ca. Arch Virol. 1987;92(1–2):121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Powell TJ, Strutt T, Reome J, et al. Priming with cold-adapted influenza A does not prevent infection but elicits long-lived protection against supralethal challenge with heterosubtypic virus. J Immunol. 2007;178(2):1030–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pearce MB, Belser JA, Houser KV, et al. Efficacy of seasonal live attenuated influenza vaccine against virus replication and transmission of a pandemic 2009 H1N1 virus in ferrets. Vaccine. 2011;29(16):2887–2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Forrest BD, Pride MW, Dunning AJ, et al. Correlation of cellular immune responses with protection against culture-confirmed influenza virus in young children. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15(7):1042–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mohn KGI, Zhou F, Brokstad KA, et al. Boosting of cross-reactive and protection-associated T cells in children after live attenuated influenza vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(10):1527–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Belshe RB, Gruber WC, Mendelman PM, et al. Efficacy of vaccination with live attenuated, cold-adapted, trivalent, intranasal influenza virus vaccine against a variant (A/Sydney) not contained in the vaccine. J Pediatr. 2000;136(2):168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Du Y, Xin L, Shi Y, et al. Genome-wide identification of interferon-sensitive mutations enables influenza vaccine design. Science. 2018;359(6373):290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Castrucci MR, Kawaoka Y. Biologic importance of neuraminidase stalk length in influenza-A virus. J Virol. 1993;67(2):759–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. García M, Misplon JA, Price GE, et al. Age dependence of immunity induced by a candidate universal influenza vaccine in mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Gostic KM, Ambrose M, Worobey M, et al. Potent protection against H5N1 and H7N9 influenza via childhood hemagglutinin imprinting. Science. 2016;354(6313):722–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Settembre EC, Dormitzer PR, Rappuoli R. H1N1: can a pandemic cycle be broken? Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(24):24ps14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Carrat F, Lavenu A, Cauchemez S, et al. Repeated influenza vaccination of healthy children and adults: borrow now, pay later? Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134(1):63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bodewes R, Kreijtz JH, Rimmelzwaan GF. Yearly influenza vaccinations: a double-edged sword? Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(12):784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Bodewes R, Kreijtz JH, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, et al. Vaccination against seasonal influenza A/H3N2 virus reduces the induction of heterosubtypic immunity against influenza A/H5N1 virus infection in ferrets. J Virol. 2011;85(6):2695–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Carragher DM, Kaminski DA, Moquin A, et al. A novel role for non-neutralizing antibodies against nucleoprotein in facilitating resistance to influenza virus. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):4168–4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. LaMere MW, Lam HT, Moquin A, et al. Contributions of antinucleoprotein IgG to heterosubtypic immunity against influenza virus. J Immunol. 2011;186(7):4331–4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. El Bakkouri K, Descamps F, De Filette M, et al. Universal vaccine based on ectodomain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A: Fc receptors and alveolar macrophages mediate protection. J Immunol. 2011;186(2):1022–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Jegerlehner A, Schmitz N, Storni T, et al. Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J Immunol. 2004;172(9):5598–5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Hashimoto G, Wright PF, Karzon DT. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against influenza virus-infected cells. J Infect Dis. 1983;148(5):785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Jegaskanda S, Job ER, Kramski M, et al. Cross-reactive influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies in the absence of neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol. 2013;190(4):1837–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Terajima M, Co MD, Cruz J, et al. High antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibody titers to H5N1 and H7N9 avian influenza A viruses in healthy US adults and older children. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(7):1052–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Jegaskanda S, Luke C, Hickman HD, et al. Generation and protective ability of influenza virus-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in humans elicited by vaccination, natural infection, and experimental challenge. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(6):945–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Co MD, Terajima M, Thomas SJ, et al. Relationship of preexisting influenza hemagglutination inhibition, complement-dependent lytic, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies to the development of clinical illness in a prospective study of A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza in children. Viral Immunol. 2014;27(8):375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, et al. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcgammaR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. DiLillo DJ, Palese P, Wilson PC, et al. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(2):605–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Henry Dunand CJ, Leon PE, Huang M, et al. Both neutralizing and non-neutralizing human H7N9 influenza vaccine-induced monoclonal antibodies confer protection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(6):800–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Jacobsen H, Rajendran M, Choi A, et al. Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies in human serum are a surrogate marker for in vivo protection in a serum transfer mouse challenge model. MBio. 2017;8(5):e01463–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Voeten JT, Bestebroer TM, Nieuwkoop NJ, et al. Antigenic drift in the influenza A virus (H3N2) nucleoprotein and escape from recognition by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2000;74(15):6800–6807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Boon AC, de Mutsert G, Graus YM, et al. Sequence variation in a newly identified HLA-B35-restricted epitope in the influenza A virus nucleoprotein associated with escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2002;76(5):2567–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Valkenburg SA, Quiñones-Parra S, Gras S, et al. Acute emergence and reversion of influenza A virus quasispecies within CD8+ T cell antigenic peptides. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Rimmelzwaan GF, Boon AC, Voeten JT, et al. Sequence variation in the influenza A virus nucleoprotein associated with escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Virus Res. 2004;103(1–2):97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Gras S, Kedzierski L, Valkenburg SA, et al. Cross-reactive CD8+ T-cell immunity between the pandemic H1N1-2009 and H1N1-1918 influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(28):12599–12604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Zharikova D, Mozdzanowska K, Feng J, et al. Influenza type A virus escape mutants emerge in vivo in the presence of antibodies to the ectodomain of matrix protein 2. J Virol. 2005;79(11):6644–6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Nachbagauer R, Choi A, Izikson R, et al. Age dependence and isotype specificity of influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-reactive antibodies in humans. MBio. 2016;7(1):e01996–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Chai N, Swem LR, Reichelt M, et al. Two escape mechanisms of influenza A virus to a broadly neutralizing stalk-binding antibody. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(6):e1005702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Tharakaraman K, Subramanian V, Cain D, et al. Broadly neutralizing influenza hemagglutinin stem-specific antibody CR8020 targets residues that are prone to escape due to host selection pressure. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(5):644–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Anderson CS, Ortega S, Chaves FA, et al. Natural and directed antigenic drift of the H1 influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk domain. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Webby RJ, Andreansky S, Stambas J, et al. Protection and compensation in the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(12):7235–7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Thomas PG, Brown SA, Keating R, et al. Hidden epitopes emerge in secondary influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):3091–3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Tamura S, Miyata K, Matsuo K, et al. Acceleration of influenza virus clearance by Th1 cells in the nasal site of mice immunized intranasally with adjuvant-combined recombinant nucleoprotein. J Immunol. 1996;156(10):3892–3900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Sui Z, Chen Q, Wu R, et al. Cross-protection against influenza virus infection by intranasal administration of M2-based vaccine with chitosan as an adjuvant. Arch Virol. 2010;155(4):535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Arinaminpathy N, Ratmann O, Koelle K, et al. Impact of cross-protective vaccines on epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of influenza. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(8):3173–3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Price GE, Lo CY, Misplon JA, et al. Mucosal immunization with a candidate universal influenza vaccine reduces virus transmission in a mouse model. J Virol. 2014;88(11):6019–6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Slepushkin AN. The effect of a previous attack of A1 influenza on susceptibility to A2 virus during the 1957 outbreak. Bull World Health Organ. 1959;20(2–3):297–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Epstein SL. Prior H1N1 influenza infection and susceptibility of Cleveland Family Study participants during the H2N2 pandemic of 1957: an experiment of nature. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(1):49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Cowling BJ, Ng S, Ma ES, et al. Protective efficacy of seasonal influenza vaccination against seasonal and pandemic influenza virus infection during 2009 in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(12):1370–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Roti M, Yang J, Berger D, et al. Healthy human subjects have CD4+ T cells directed against H5N1 influenza virus. J Immunol. 2008;180(3):1758–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Kreijtz JH, de Mutsert G, van Baalen CA, et al. Cross-recognition of avian H5N1 influenza virus by human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte populations directed to human influenza A virus. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5161–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Zhong W, Reed C, Blair PJ, et al. Serum antibody response to matrix protein 2 following natural infection with 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus in humans. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(7):986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Park JK, Han A, Czajkowski L, et al. Evaluation of preexisting anti-hemagglutinin stalk antibody as a correlate of protection in a healthy volunteer challenge with influenza A/H1N1pdm virus. MBio. 2018;9(1):e02284–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. McMichael AJ, Gotch FM, Noble GR, et al. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to influenza. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Sridhar S, Begom S, Bermingham A, et al. Cellular immune correlates of protection against symptomatic pandemic influenza. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Wilkinson TM, Li CK, Chui CS, et al. Preexisting influenza-specific CD4+ T cells correlate with disease protection against influenza challenge in humans. Nat Med. 2012;18(2):274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. van Doorn E, Liu H, Ben-Yedidia T, et al. Evaluating the immunogenicity and safety of a Biondvax-developed universal influenza vaccine (Multimeric-001) either as a standalone vaccine or as a primer to H5N1 influenza vaccine: phase IIb study protocol. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(11):e6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Pleguezuelos O, Robinson S, Fernández A, et al. A synthetic influenza virus vaccine induces a cellular immune response that correlates with reduction in symptomatology and virus shedding in a randomized phase Ib live-virus challenge in humans. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22(7):828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Francis JN, Bunce CJ, Horlock C, et al. A novel peptide-based pan-influenza A vaccine: a double blind, randomised clinical trial of immunogenicity and safety. Vaccine. 2015;33(2):396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Lillie PJ, Berthoud TK, Powell TJ, et al. Preliminary assessment of the efficacy of a T-cell-based influenza vaccine, MVA-NP+M1, in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(1):19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Antrobus RD, Lillie PJ, Berthoud TK, et al. A T cell-inducing influenza vaccine for the elderly: safety and immunogenicity of MVA-NP+M1 in adults aged over 50 years. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e48322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Antrobus RD, Coughlan L, Berthoud TK, et al. Clinical assessment of a novel recombinant simian adenovirus ChAdOx1 as a vectored vaccine expressing conserved influenza A antigens. Mol Ther. 2014;22(3):668–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Berthoud TK, Hamill M, Lillie PJ, et al. Potent CD8+ T-cell immunogenicity in humans of a novel heterosubtypic influenza A vaccine, MVA-NP+M1. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Antrobus RD, Berthoud TK, Mullarkey CE, et al. Coadministration of seasonal influenza vaccine and MVA-NP+M1 simultaneously achieves potent humoral and cell-mediated responses. Mol Ther. 2014;22(1):233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. BiondVax Pharmaceuticals Ltd A Pivotal Trial to Assess the Safety and Clinical Efficacy of the M-001 as a Standalone Universal Flu Vaccine. 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03450915?term=BiondVax&rank=2. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- 152. Ledgerwood JE, Wei CJ, Hu Z, et al. DNA priming and influenza vaccine immunogenicity: two phase 1 open label randomised clinical trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):916–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. PATH Safety and Immunogenicity of a Live-Attenuated Universal Flu Vaccine Followed by an Inactivated Universal Flu Vaccine. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03300050. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- 154. Paules CI, Marston HD, Eisinger RW, et al. The pathway to a universal influenza vaccine. Immunity. 2017;47(4):599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, et al. A universal influenza vaccine: the strategic plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis. 2018:218(3):347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Jang YH, Seong BL. Options and obstacles for designing a universal influenza vaccine. Viruses. 2014;6(8):3159–3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Smith LR, Wloch MK, Ye M, et al. Phase 1 clinical trials of the safety and immunogenicity of adjuvanted plasmid DNA vaccines encoding influenza A virus H5 hemagglutinin. Vaccine. 2010;28(13):2565–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Hoft DF, Babusis E, Worku S, et al. Live and inactivated influenza vaccines induce similar humoral responses, but only live vaccines induce diverse T-cell responses in young children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(6):845–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. World Health Organization Tables on clinical evaluation of influenza vaccines. http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/influenza/clinical_evaluation_tables/en/. First published 2007. Most recently updated November 15, 2017. Accessed June 13, 2018.

- 160. World Health Organization Pandemic/potentially pandemic influenza vaccines. http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/influenza/Table_clinical_evaluation_influenza_pandemic.xlsx?ua=1. First published 2007. Most recently updated November 15, 2017. Accessed June 13, 2018.