Abstract

Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) selectively catalyze carotenoids, forming smaller apocarotenoids that are essential for the synthesis of apocarotenoid flavor, aroma volatiles, and phytohormone ABA/SLs, as well as responses to abiotic stresses. Here, 19, 11, and 10 CCD genes were identified in Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana tomentosiformis, and Nicotiana sylvestris, respectively. For this family, we systematically analyzed phylogeny, gene structure, conserved motifs, gene duplications, cis-elements, subcellular and chromosomal localization, miRNA-target sites, expression patterns with different treatments, and molecular evolution. CCD genes were classified into two subfamilies and nine groups. Gene structures, motifs, and tertiary structures showed similarities within the same groups. Subcellular localization analysis predicted that CCD family genes are cytoplasmic and plastid-localized, which was confirmed experimentally. Evolutionary analysis showed that purifying selection dominated the evolution of these genes. Meanwhile, seven positive sites were identified on the ancestor branch of the tobacco CCD subfamily. Cis-regulatory elements of the CCD promoters were mainly involved in light-responsiveness, hormone treatment, and physiological stress. Different CCD family genes were predominantly expressed separately in roots, flowers, seeds, and leaves and exhibited divergent expression patterns with different hormones (ABA, MeJA, IAA, SA) and abiotic (drought, cold, heat) stresses. This study provides a comprehensive overview of the NtCCD gene family and a foundation for future functional characterization of individual genes.

Keywords: CCDs, Nicotiana tabacum, genome-wide identification, hormones and abiotic stresses, gene expression

1. Introduction

Carotenoids, as C40 isoprenoid compounds, contribute to a series of important biological functions in vivo. As accessory photosynthetic pigments and general antioxidants, they play important roles in harvesting light and preventing photooxidation [1,2]. Carotenoids also serve as yellow, orange, and red pigments in plant leaves, flowers, fruits, and other tissues. The cleavage of carotenoids can produce various apocarotenoids, which are a diverse class of natural compounds that act as signaling molecules, related to hormones, volatiles, and signals, in many plants [3,4,5,6].

Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) is an important enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of various carotenoids into smaller apocarotenoids [7]. The CCD gene was first isolated from maize (originally named Vp14) [8]. Subsequently, CCDs were identified in many other plant species. To date, most CCDs have been classified into two subfamilies, namely carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (NCEDs), including nine clades (CCD1, 4, 7, and 8; and NCED2, 3, 5, 6, and 9), according to the classification method in Arabidopsis thaliana [9]. Additionally, carotenoid oxygenase genes have also been classified into five clades (namely CCD1, 4, 7, and 8 and NCEDs), based on phylogeny and gene function [4,10]. In addition to these, a new group, named CCD-Like (CCDL), was also identified in Solanum lycopersicum [11], Fragaria vesca [12], and Malus domestica [13].

Members of the CCD subfamily are involved in the synthesis of apocarotenoid flavor, aroma volatiles, and strigolactones (SLs), according to differences in substrates and regioselectivity [14,15]. They also take part in responses to various abiotic stresses, pigmentation, photosynthesis, and photoprotection [13,14]. Among these, CCD1 was reported to cleave C40-carotenoids and C27-apocarotenoids at the 9, 10 (9′, 10′) and 5, 6 (5′, 6′) double bonds in vivo to form C13/C14-compounds (such as α/β-ionone), which act as important aroma and flavor substances in many plants [16,17,18]. For example, LeCCD1, PhCCD1, OfCCD1, and CmCCD1 contribute to the formation of the flavor volatile β-ionone in F. vesca, Petunia hybrida, Osmanthus fragrans Lour, and Cucumis melo L in vivo, respectively [19,20,21]. CCD4 also functions in cleavage of the 9, 10 (9′, 10′) double bond, which has important roles in forming color, flavor, and aroma properties of flowers and fruits [22,23]. Further, PpCCD4 was reported to determine the flesh color of peach [24], CmCCD4a contributes to the formation of the white color in Chrysanthemum [25], and decreases in StCCD4 activity increase the content of carotenoids in potato tubers [26]. Moreover, the ablation of OsCCD4a via RNA interference was found to enhance carotenoid content in rice seed endosperms and leaves [27]. Additionally, CsCCD4b is highly responsive to salt and dehydration stresses in Crocus sativus [28]. CCD7 and CCD8 are mainly involved in the biosynthesis of SL. CCD7 can cleave 9-cis-β-carotene to produce C27 9-cis-β-apo-10′-carotenal, which is then cleaved by CCD8 to generate C18 13′-apo-β-carotenal, the precursor of phytohormone SLs [29,30]. Recently, studies have also found that SLs not only control the shoot branch but also regulate rhizosphere signaling and further affect plant architecture, as well as responses to biotic and abiotic stresses in plants [29,31,32].

Members of the NCED subfamily are enzymes that specifically cleave the 11, 12 (11′, 12′) double bond of 9-cis-epoxy carotenoids to form C15-xanthoxin, which is an important rate-limiting step in synthesis of the phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) [33,34]. ABA exerts considerable physiological effects during plant developmental processes under normal and stress conditions, including seed dormancy, leaf senescence, and responses to various environmental stresses, among others [35,36]. In avocado, PaNCED1 and PaNCED3 encode proteins that can synthesize xanthoxin, the precursor of ABA, in vitro [34]. Further, the overexpression of VaNCED1 and VuNCED1 leads to the accumulation of ABA and enhances the expression of drought-responsive genes in grape and cowpea [37,38]. Of note, NCED3 was especially identified as the first indispensable rate-limiting enzyme required for the biosynthesis of ABA [8,39,40]. Our previous study revealed that RNA interference-mediated knockdown of NtNCED3 could reduce drought tolerance and impair plant growth through ABA feedback regulation in Nicotiana tabacum [41]. In A. thaliana, AtNCED3, together with AtNCED5, is thought to contribute to the production of ABA, which then affects the regular growth of plants [39]. In addition, AtNCED6 and AtNCED9 are necessary for ABA biosynthesis during seed development [42]. These observations illustrate that NCEDs regulate ABA synthesis, and then affect ABA-mediated signals involved in plant metabolic status and downstream stress responses.

Tobacco is not only an important model plant but also one of the most economically significant crops [40]. It is thus important to identify NCED and CCD gene family members in this species due to the importance of apocarotenoids and phytohormone ABA/SLs in plant development and stress responses. Although the CCD gene family has been researched in some other species, such as Capsicum annuum L [43], F. vesca [12], and M. domestica [13], among others, there have still been only a few similar studies conducted on tobacco to date. Here, we first identified and investigated the entire CCD gene family, including 19 CCD gene family members in allotetraploid N. tabacum, as well as 10 and 11 members in their two ancestors N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis, respectively. Then, we systematically analyzed the phylogeny, gene structure, conserved motifs, synteny, cis-elements, subcellular and chromosomal localization, and the molecular evolution of the CCD gene family. Three-dimensional (3D) structures of CCD proteins were also modeled. To obtain functional information on CCDs, their expression patterns were analyzed by quantitative real-time (qRT) PCR in different tissues and in response to different hormones (ABA, MeJA, IAA, SA) and abiotic (drought, cold, heat) stress treatments. Our results herein will provide a solid foundation for further functional studies on CCD genes in tobacco.

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characterization of CCD

To identify CCD family members in the genomes of the tetraploid species N. tabacum (2n = 48) and its two progenitor diploid species, N. tomentosiformis (2n = 24) and N. sylvestris (2n = 24), the coding sequences of nine Arabidopsis AtCCDs were used as queries to search against the China Tobacco Genome Database V2.0 (http://www.tobaccodb.org/) (restricted) in the China Tobacco Gene Research Centre. Based on sequence similarity to AtCCDs, in total, 19, 11, and 10 CCD genes were retrieved from the genomes of N. tabacum, N. tomentosiformis, and N. sylvestris, respectively (Table 1). The CCD sequences of S. lycopersicum and C. annuum were also downloaded from Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/). The CCD gene families in tobacco were named according to previous reports and their homologies to Arabidopsis, S. lycopersicum, and C. annuum CCD family genes in the phylogenetic tree, based on species’ abbreviations [9,11,43].

Table 1.

The list of CCD gene essential information in tobacco.

| Species | Gene Name | Gene ID | Gene Length (bp) | ORF Length (bp) | Amino Acid | MW (kDa) | PI | Chromosome | Protein Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana tabacum | NtCCD1a | Ntab0245430 | 8618 | 1641 | 546 | 61.080 | 6.01 | Chr02 | Cytoplasm |

| NtCCD1b | Ntab0755880 | 10472 | 1683 | 560 | 62.932 | 6.51 | Chr06 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtCCD4a | Ntab0608760 | 3600 | 1803 | 600 | 65.858 | 7.16 | Chr09 | Chloroplast | |

| NtCCD4b | Ntab0943160 | 3449 | 1806 | 601 | 65.936 | 7.24 | Chr20 | Chloroplast | |

| NtCCD4c | Ntab0104800 | 2941 | 1803 | 600 | 65.709 | 6.44 | Chr08 | Chloroplast | |

| NtCCD7a | Ntab0292410 | 9135 | 1956 | 650 | 73.341 | 6.43 | Chr13 | Mitochondrion | |

| NtCCD7b | Ntab0552870 | 4928 | 1953 | 651 | 73.260 | 6.43 | Chr06 | Mitochondrion | |

| NtCCD8a | Ntab0551270 | 4366 | 1671 | 556 | 62.350 | 5.98 | Chr18 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtCCD8b | Ntab0369080 | 3707 | 1668 | 555 | 62.194 | 6.18 | Chr06 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtCCDLa | Ntab0667500 | 3102 | 1593 | 530 | 59.969 | 5.85 | Chr06 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtCCDLb | Ntab0429710 | 3221 | 1572 | 523 | 59.214 | 5.56 | Ntab_scaffold_247 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtCCDLc | Ntab0264020 | 3002 | 1470 | 489 | 55.733 | 6.34 | Ntab_scaffold_247 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtNCED2 | Ntab0264020 | 1800 | 1800 | 599 | 66.844 | 7.60 | Ntab_scaffold_176 | Chloroplast | |

| NtNCED3a | Ntab0266320 | 1830 | 1830 | 609 | 67.754 | 7.28 | Chr11 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtNCED3b | Ntab0214800 | 1842 | 1842 | 613 | 68.191 | 7.66 | Chr07 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtNCED5a | Ntab0972510 | 1806 | 1806 | 601 | 67.018 | 6.12 | Chr23 | Chloroplast | |

| NtNCED5b | Ntab0027880 | 1806 | 1806 | 601 | 67.134 | 6.40 | Chr24 | Chloroplast | |

| NtNCED6a | Ntab0557140 | 1795 | 1746 | 581 | 64.607 | 8.18 | Chr16 | Chloroplast | |

| NtNCED6b | Ntab0434870 | 8137 | 1608 | 535 | 60.419 | 4.60 | Chr15 | Cytoplasm | |

| Nicotiana sylvestris | NsyCCD1a | Nsyl0144600 | 13565 | 1707 | 568 | 63.685 | 6.49 | Nsyl_scaffold_1522 | Cytoplasm |

| NsyCCD1b | Nsyl0177010 | 8624 | 1647 | 548 | 61.316 | 6.33 | Nsyl_superscaffold_202 | Cytoplasm | |

| NsyCCD4 | Nsyl0462250 | 2426 | 1803 | 600 | 65.691 | 6.62 | Nsyl_superscaffold_41 | Chloroplast | |

| NsyCCD7 | Nsyl0304670 | 9105 | 1953 | 650 | 73.341 | 6.43 | Nsyl_superscaffold_23 | Mitochondrion | |

| NsyCCD8 | Nsyl0145940 | 4366 | 1671 | 556 | 62.350 | 5.98 | Nsyl_superscaffold_190 | Cytoplasm | |

| NsyCCDL | Nsyl0401980 | 3221 | 1572 | 523 | 59.214 | 5.56 | Nsyl_superscaffold_155 | Cytoplasm | |

| NsyNCED2 | Nsyl0071360 | 1800 | 1800 | 599 | 66.844 | 7.60 | Nsyl_superscaffold_251 | Chloroplast | |

| NsyNCED3 | Nsyl0483670 | 1830 | 1830 | 609 | 67.754 | 7.28 | Nsyl_superscaffold_179 | Cytoplasm | |

| NsyNCED5 | Nsyl0074010 | 1806 | 1806 | 601 | 67.020 | 6.12 | Nsyl_scaffold_1118 | Chloroplast | |

| NsyNCED6 | Nsyl0472000 | 1518 | 1518 | 505 | 56.325 | 5.83 | Nsyl_superscaffold_26 | Cytoplasm | |

| Nicotiana tomentosiformis | NtoCCD1a | Ntom0051870 | 8169 | 1647 | 548 | 61.657 | 6.27 | Ntom_scaffold_148 | Cytoplasm |

| NtoCCD1b | Ntom0051880 | 10899 | 1641 | 546 | 61.138 | 6.06 | Ntom_scaffold_14 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtoCCD4a | Ntom0284420 | 3600 | 1803 | 600 | 65.858 | 7.16 | Ntom_scaffold_554 | Chloroplast | |

| NtoCCD4b | Ntom0290610 | 3458 | 1806 | 601 | 65.940 | 6.58 | Ntom_superscaffold_38 | Chloroplast | |

| NtoCCD7 | Ntom0214430 | 5121 | 1953 | 650 | 73.176 | 6.43 | Ntom_scaffold_374 | Mitochondrion | |

| NtoCCD8 | Ntom0326520 | 3707 | 1668 | 555 | 62.183 | 6.30 | Ntom_scaffold_709 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtoCCDLa | Ntom0006270 | 3289 | 1668 | 555 | 62.702 | 6.34 | Ntom_scaffold_103 | Chloroplast | |

| NtoCCDLb | Ntom0326460 | 3086 | 1563 | 523 | 59.238 | 6.23 | Ntom_scaffold_709 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtoNCED3 | Ntom0303590 | 1842 | 1842 | 613 | 68.177 | 7.66 | Ntom_scaffold_600 | Cytoplasm | |

| NtoNCED5 | Ntom0232040 | 1806 | 1806 | 601 | 67.094 | 6.37 | Ntom_superscaffold_17 | Chloroplast | |

| NtoNCED6 | Ntom0304970 | 1752 | 1752 | 583 | 64.887 | 8.35 | Ntom_superscaffold_63 | Chloroplast |

The basic information for NtCCDs, NsyCCDs, and NtomCCDs, including the gene IDs, lengths of genes, open reading frames (ORFs) and deduced amino acid sequences, molecular weights (Mws), isoelectric points (pIs), and chromosomal and subcellular locations are listed in Table 1. In N. tabacum, gene and ORF lengths ranged from 1795 to 10472 bp and 1470 to 1956 bp, respectively. The deduced protein lengths varied from 489 to 650 amino acids, the Mw from 55.733 to 73.341 kDa, and pI from 4.60 to 8.18. There were four NtCCDs genes on chromosome 6, and chromosomes 2, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 20, 23, and 24 contained one each. The other three NtCCD genes remained on scaffolds.

In N. sylvestris, the gene lengths of NsyCCDs varied from 1518 to 13565 bp, and ORF lengths ranged from 1518 to 1953 bp. Regarding deduced NsyCCDs, protein lengths varied from 505 to 650 amino acids, Mw from 56.325 to 73.341 kDa, and pI from 5.56 to 7.60. Moreover, two NsyCCD genes remained on scaffolds, and eight genes remained on superscaffolds. For NtomCCDs, gene and ORF lengths ranged from 1752 to 10899 bp and from 1563 and 1953 bp, respectively. For deduced NtomCCDs, protein lengths varied from 523 to 650 amino acids, Mw from 59.238 to 73.176 kDa, and pI from 6.06 to 8.35. Three NtoCCD genes remained on scaffolds, and eight genes remained on superscaffolds.

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of CCD

To better determine the evolutionary relationships among CCD proteins, an unrooted phylogenetic tree containing 66 CCD proteins from six species was constructed, using the neighbor-joining method in Phylip3.69 program (Figure 1). According to tree topology, all CCD proteins could be classified into two subfamilies (CCDs and NCEDs) and nine groups, named CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, CCD8, CCDL, NCED2, NCED3, NCED5, and NCED6, in accordance with the nomenclature of Tan [9], Wei [11], and Zhang [43] et al. Based on this grouping, for the CCD subfamily, two genes each from N. tabacum, N. sylvestris, and N. tomentosiformis belonged to the CCD1 group, whereas three NtCCDs, one NsyCCD, and two NtoCCDs fell into the CCD4 group. In addition, each of the CCD7 and CCD8 groups contained two NtCCDs, one NsyCCD, and one NtoCCD. Additionally, the CCDL group, which was recently proposed first in tomato [11], included three genes in N. tabacum, only one in N. sylvestris, and two in N. tomentosiformis, whereas none was identified in Arabidopsis, suggesting that CCDL proteins were probably expanded only within some species. Furthermore, phylogenetic relationships also revealed that CCD7, CCDL, and CCD8 groups might share the same ancestral gene, whereas the CCD1 and CCD4 groups were thought to have evolved more similarly. In addition, it could be speculated that the NCED subfamily had evolved from the CCD1 group. Moreover, only one NCED2 protein was found in N. tabacum and N. sylvestris. In addition, NCED3, NCED5, and NCED6 groups each contained two genes in N. tabacum and a unique NCED protein in N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of CCD proteins from six species. Clustalx 6.0 was used to align the multiple sequences. Phylip3.69 was used to build the unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) tree with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The CCD proteins of Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana sylvestris, Nicotiana tomentosiformis, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, and Capsicum annuum were marked by red circle, pink square, light blue diamond, green triangle, red hollow circle, and blue hollow square, respectively. The protein/gene IDs in Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana sylvestris, and Nicotiana tomentosiformis are listed in Table 1, and the other three species, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, and Capsicum annuum, are in Supplementary Table S1, respectively.

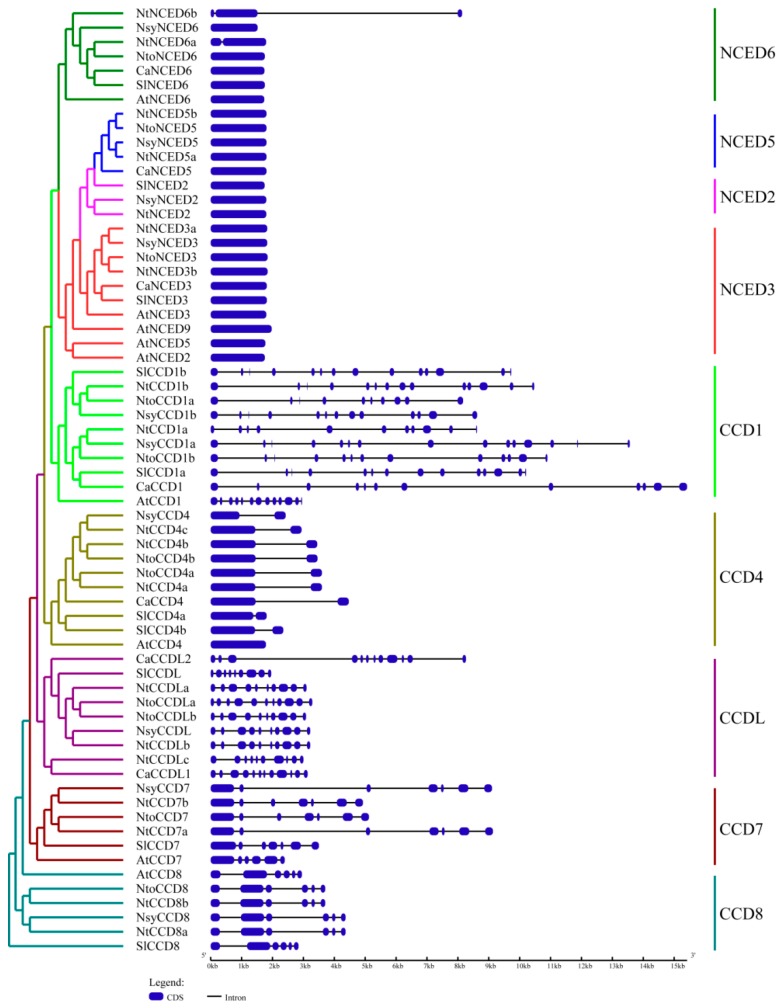

2.3. Gene Structures and Conserved Motifs Analysis of CCDs

To further obtain insights into the exon/intron structures of the CCD family, we compared their exon/intron arrangements by using GSDS online tools. As shown in Figure 2, the numbers of exons/introns were usually similar in the same group. All members of the NCED subfamily were intron-deficient (except NtNCED6a and NtNCED6b). Further, the CCD1 group had the most introns, ranging from 9 to 14, and only one intron was found in the CCD4 group. Five introns were present in the CCD8 group. Moreover, the CCDL group contained 8–11 exons, whereas six introns were found in the CCD7 group, except for AtCCD7, which had five introns.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of exon/intron structures of CCD genes from Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana sylvestris, Nicotiana tomentosiformis, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, and Capsicum annuum. The unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) evolutionary tree (left panel) was constructed by using Phylip3.69, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The protein/gene IDs in Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana sylvestris, and Nicotiana tomentosiformis are listed in Table 1, and the other three species, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, and Capsicum annuum, are in Supplementary Table S1, respectively. Exon–intron analyses of CCD genes were performed with GSDS 2.0 (right panel). Blue boxes and black lines correspond to exons (CDS) and introns, respectively.

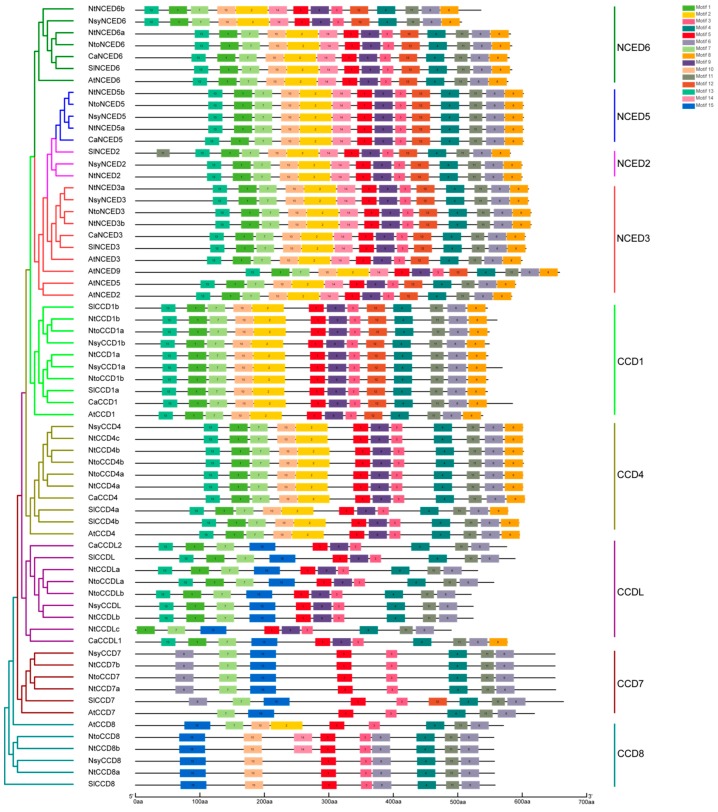

All CCD proteins comprised an RPE65 domain (retinal pigment epithelial membrane protein) annotated based on the NCBI CDD database. To investigate the motif features of CCD proteins, 15 distinct motifs, representing part of the RPE65 domain, were identified with high e-values, using the MEME tool. The schematic distribution is shown in Figure 3. As expected, CCD proteins with close relationships showed similar motif compositions. Further, all groups of the CCD and NCED protein subfamilies contained motifs 3, 4, 5, 6, and 11, suggesting that these motifs might be important and responsible for their common functions. Of which, motifs 2, 5, 3, and 8 contained four conserved iron-ligating histidine (H) residues, and motifs 2, 4, and 11 contained conserved glutamate (E) or aspartate (D) residues required for activity. Exceptionally, some conserved residues were not found in these motifs of CCD7 and CCD8 and the CCDL group (Supplementary Table S2). In general, NCED subfamily proteins contained all 1–14 motifs, with motif 12 being specific to them. Motif 15 was absent in the NCED subfamily. Howbeit CCD proteins contained fewer motifs. Motif 14 and 15 were absent in the CCD1 group. In addition, CCD4 proteins lacked motifs 12, 14, and 15, and CCDL group proteins possessed 10 conserved motifs, with the absence of motifs 2, 8, 10, 12, and 14. Remarkably, NtCCDLc also lacked motif 13, and CaCCDL1 contained motif 8. Compared to those of the CCDL group, CCD7 group proteins lacked motifs 1, 9, and 13, and all CCD7 proteins had two motif 6s, except for AtCCD7. CCD8 harbored 8–9 motifs. In summary, these results indicated that each group of CCD subfamily proteins has different motif compositions, which further supports the topology of the phylogenetic tree.

Figure 3.

The conserved motifs of CCD proteins from Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana sylvestris, Nicotiana tomentosiformis, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, and Capsicum annuum. In the left panel, the unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) evolutionary tree was constructed by using Phylip3.69, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The protein/gene IDs in Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana sylvestris, and Nicotiana tomentosiformis are listed in Table 1, and the other three species, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, and Capsicum annuum are in Supplementary Table S1, respectively. In the right panel, different-color boxes represent different motifs.

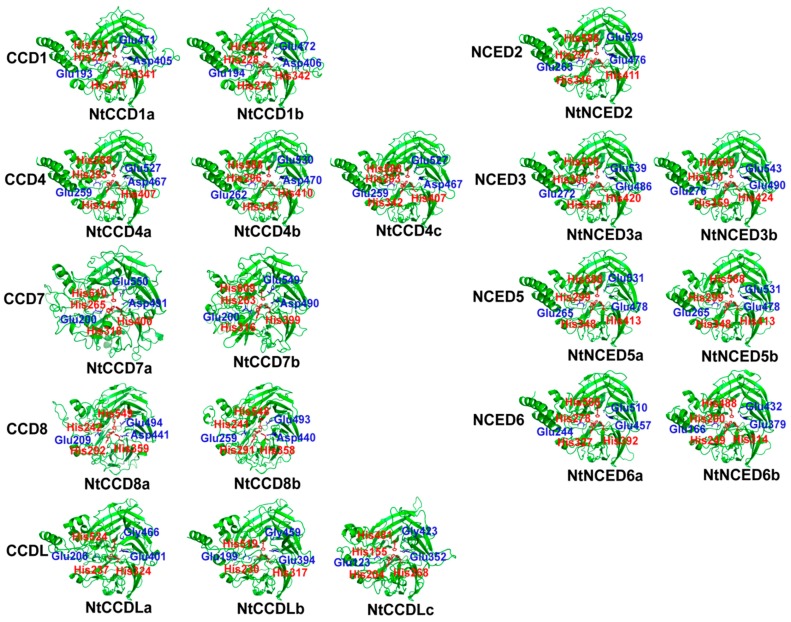

2.4. Predicted Three-Dimensional (3D) Structures of NtCCDs

Tertiary structure prediction results indicated that CCD proteins are mainly comprised of random coils and β-strands (Figure 4). Moreover, proteins in the same group were found to be structurally similar, although there were some differences in the random coils. A comparable analysis of the 3D structures of different groups of CCDs revealed that they all have a conserved single loop composed of seven bladed β-sheets and one helix in these models, and that they also contained four conserved iron-ligating histidines and three glutamate or aspartate residues required for enzyme activity. The exception was the NtCCDL group, in which one of the glutamates was replaced with glycine in three NtCCDL proteins. Simultaneously, NtCCDLa and NtCCDLb lacked one conserved histidine (Supplementary Table S2). A comparison between different groups indicated that the structures of NtNCED subfamily proteins were more similar to those of the NtCCD1 and NtCCD4 groups. In contrast, NtCCD7, NtCCD8, and NtCCDL groups showed similar structures and possessed fewer or shorter α-helixes at N- and C-termini, which comprised the main differences between other CCD and NCED groups.

Figure 4.

The predicted 3D structures of NtCCDs family proteins. The models were built with SWISS-MODEL and displayed with PyMOL software. The conserved four iron-ligating histidine (H) residues, and the conserved glutamates or aspartates (glycine in CCDL group) required for activity were marked with red and blue sticks and characters.

2.5. Chromosomal Locations and Gene Duplication Analysis of NtCCDs

We further determined the localizations of the CCD gene family on chromosomes of N. tabacum. Information from physical maps (including the numbers, lengths, and gene loci) of each N. tabacum chromosome was obtained from the China Tobacco Genome Database (V2.0). In general, 19 NtCCDs genes were unevenly distributed throughout 13 chromosomes and three genes were anchored to unattributed scaffolds (Figure 5, Table 1). No NtCCDs genes were mapped to the other 11 tobacco chromosomes. Four NtCCDs genes (NtCCD1b, NtCCD7b, NtCCD8b, and NtCCDLa) were located on chromosome 6, and 12 other chromosomes (2, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 20, 23, 24) harbored only a single NtCCD gene each. In addition, due to a lack of physical map information for N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis, NsyCCDs and NtoCCDs could only be located on the scaffolds but not on the chromosomes of these species.

Figure 5.

Chromosomal locations of NtCCDs genes on Nicotiana tabacum chromosome. The relative chromosome length scaled in megabases (Mb) is indicated on the left. The bars on chromosomes indicate the positions of the NtCCDs genes. The figure was generated and modified, using the MapGene2Chrom program.

Gene duplication events occurred at least once during evolution in tetraploid tobacco. Gene duplication analysis might thus provide helpful information regarding the expansion of the CCD gene family. In our study, we analyzed the tandem duplication, as well as segmental duplication, of NtCCD genes. As shown in Figure 6, all of these paralogs (except for NtCCD1b, NtCCD7b, NtCCD8b, and NtCCDLa) were found to be located on different chromosomes, indicating that the homologous pairs were probably mainly produced by a whole-genome duplication (WGD) event and that segmental duplication was more important for the expansion of the NtCCD gene family. Adjacent homologous genes on the same chromosome are thought to be probably the result of a tandem duplication; however, NtCCD1b, NtCCD7b, NtCCD8b, and NtCCDLa did not share similar gene structures and motif compositions (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Moreover, according to the phylogenetic tree, they might have originated from an ancestor of tetraploid tobacco, namely N. sylvestris or N. tomentosiformis, suggesting that these genes might be preferential genes that were retained after WGD and subsequent frequent chromosomal arrangements.

Figure 6.

Gene duplications of the NtCCDs genes in Nicotiana tabacum. The relationships between CCD homologs were verified and visualized by using the Circos tool in TBtools software.

2.6. Subcellular Localization of CCD Proteins

The N-terminal sorting signals and chloroplast transporter peptide (cTP) of CCD proteins were detected by using the online tools iPSORT and ChloroP Server program. Results showed that except for NsyNCED6, 15 CCD proteins in CCD4, NCED2, NCED5, and NCED6 groups of N. tabacum, N. sylvestris, and N. tomentosiformis had a chloroplast-targeting peptide at the N-termini, suggesting that these enzymes might be chloroplast-localized (Table 1). All CCD7 group proteins also had a mitochondrion-targeting peptide, and might be thus located at the mitochondrion. No sorting signal was detected in the remaining 21 CCD proteins. Then, we further investigated the subcellular localization of these CCD family members, using the online tools Plant-mPloc and ProtComp. The results showed that they were predicted to be cytoplasmic.

Using the transient expression methods induced by the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, the cellular distributions of NtCCD1a proteins labeled by green fluorescent protein (GFP) were further investigated in tobacco leaves epidermal cells. In the leaves of the transformed control vector plant, the fluorescence of the GFP was detected in the cytoplasm and nucleus. After transient expression of NtCCD1a-GFP fusion proteins in tobacco leaves, the GFP signals were also merged with the nuclear localization signals (NLS) of the nucleus-anchored marker (Figure 7), suggesting that NtCCD1a was localized to both the cytoplasm and nucleus.

Figure 7.

Subcellular localization of the NtCCD1a protein. NtCCD1a-GFP fusion proteins were transiently expressed in tobacco epidermal cells. Images were observed by laser confocal microscopy. Scale bar = 20 μm.

2.7. Cis-acting Elements Analysis of NtCCDs Promoters

The promoter is an upstream segment of the gene, which plays important roles in the initiation of gene transcription. In this study, cis-acting elements of NtCCD promoters (2000 bp sequences upstream of ATG) were predicted using PlantCARE software. Finally, 18 potential cis-acting elements involved in light-responsiveness, hormone-responsiveness, and physiological stress (such as salt, drought, cold, heat, etc.) were identified in NtCCD promoters. The results indicating main elements and locations are as follows (Figure 8). Various light-responsive elements such as a GT1-motif, G-Box, ACE, and Sp1-binding site were found to exist in every NtCCD promoter. Especially, NtCCD7b promoters harbored five G-Box elements. The MRE is a MYB-binding site, which is present in some promoters and also involved in light responsiveness. The ABRE is involved in ABA responsiveness and can be found in most promoters. Among these, the majority has two or more ABREs. Specifically, the NtCCD4a promoter was found to contain nine ABREs based on tandem repeats, whereas the NtCCD8a promoter had five. Gibberellin-responsive elements include a P-box, GARE-motif, and TATC-box and appear in many promoters. MeJA-responsive elements, including the CGTCA-motif and TGACG-motif, were suggested to exist in most NtCCD promoters, except for those of NtCCD1a, NtCCDLa, NtNCED3a, and NtNCED5a. Salicylic acid responsive elements include a TCA-element (present in half of promoters) and SARE (only emerging in the NtCCD7b promoter). The AuxRR-core and TGA-element, involved in auxin responsiveness, was present in some promoters. TC-rich repeats as defense and stress responsive elements were found to exist in six promoters. Drought-inducibility elements (MBS) were found in some promoters, especially that of NtCCDLa, which has four MBSs. Six NtCCD promoters (NtNCED3a, NtNCED6b, NtCCD1b, NtCCD4c, NtCCD8a, and NtCCD8b) were identified has having a low-temperature responsive element (LTR). Overall, these results indicated that the expression of NtCCD family genes might be regulated by diverse cis-elements within the promoters related to light response, hormone and defense signal transduction, and abiotic stresses during tobacco growth.

Figure 8.

Promoter cis-elements analysis of NtCCDs. Left panel, the unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) evolutionary tree. Middle panel, the number of cis-elements in CCD promoter. Right panel, the schematic distribution of cis-elements. Some cis-elements may overlap with others. Different cis-acting elements were displayed with different-color boxes. a–n: the foreground branch labeled in the molecular evolution analysis followed.

2.8. Potential MicroRNA Target Sites of NtCCDs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), usually small non-coding RNAs of approximately 22 nucleotides, regulate target genes related to plant development, responses to biotic/abiotic stresses, stress adaptation, and signal transduction via RNA silencing and post-transcriptional regulation mechanisms. The potential miRNA-target sites in NtCCD transcripts were searched, using psRNATarget database online. By maintaining a cut-off threshold of four as the search parameter, seven miRNAs from five families comprising target sites in five NtCCD family genes were identified, with an expectation score (E) ranging from 3.0 to 4 (Table 2). Among these, NtCCD1a and NtCCDLc contained target sites for multiple miRNAs, whereas NtNCED3a, NtNCED3b, NtNCED6a, and NtCCD4a comprised target sites for a single miRNA. As an important factor for target recognition, the numerical value of target accessibility (UPE) for the target site represents the energy required to bind and cleave target mRNA, and a lower energy means a greater possibility of interactions between miRNA and the target site. Here, UPE varied from 8.152 (nta-miR159) to 22.68 (nta-miR159 and nta-miR319b).

Table 2.

The potential miRNA target sites in NtCCDs transcripts.

| miRNA_Acc. | Target_Acc. | Expectation | UPE | miRNA Length | Target Start | Target End | Inhibition | Multiplicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nta-miR319a | NtCCDLc | 3 | 21.947 | 21 | 1266 | 1286 | Cleavage | 1 |

| nta-miR319b | NtCCDLc | 3 | 22.68 | 21 | 1265 | 1285 | Cleavage | 1 |

| nta-miR159 | NtCCDLc | 3 | 22.68 | 21 | 1265 | 1285 | Cleavage | 1 |

| nta-miR6150 | NtNCED3a | 3.5 | 10 | 22 | 1433 | 1454 | Cleavage | 1 |

| nta-miR6150 | NtNCED3b | 3.5 | 11.413 | 22 | 1445 | 1466 | Cleavage | 1 |

| nta-miR6150 | NtNCED6a | 4 | 21.187 | 22 | 1112 | 1134 | Translation | 1 |

| nta-miR6148b | NtCCD1a | 4 | 14.183 | 21 | 645 | 665 | Translation | 1 |

| nta-miR6164a | NtCCD1a | 4 | 18.268 | 21 | 356 | 376 | Translation | 1 |

| nta-miR6164b | NtCCD1a | 4 | 18.268 | 21 | 356 | 376 | Translation | 1 |

| nta-miR159 | NtCCD4a | 4 | 8.152 | 21 | 324 | 344 | Translation | 1 |

2.9. Molecular Evolution of NtCCDs

The Ka and Ks represent the nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution rate. The Ka/Ks (ω) value that is greater than, less than, and equal to 1 represents positive, negative (purify), and neutral selection, respectively [44]. To determine the possible selection pressures acting on NtCCDs, we analyzed whether positive selection existed during the evolution of NtCCDs by using the software EasyCodeML1.2. For the site model (Table 3), one-ratio model (M0), based on the average over all sites and branches, yielded an estimated ω = 0.09246. This result indicated that purifying selection dominated the evolution of tobacco CCDs. However, this model has its limitations. Then, the heterogeneous selective pressure among sites were tested, using different models. The discrete model (M3), which assumes variation among sites but no variation among branches, was applied to the sequences. Likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) of M0 against M3 indicated significant variation in selective pressure among the sites. Neutral model M1a assumes sites with two categories (0 < ω0 < 1 and ω1 = 1), and selection model M2a adds a third kind of site (ω > 1). LRTs of M1a against M2a didn’t find positive selection site. Model M7, M8, and M8a were used to estimate the spatial distribution of each site. LRTs of M7 against M8 and M8a against M8 both didn’t find a positive selection site. These site models found no evidence of a strong role of positive selection affecting the evolution of tobacco CCD genes, which implied that they were under purifying selection.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates and likelihood values for NtCCDs using the site model.

| Model | Np | Ln L | Estimates of Parameters | RT Pairs | LRT p-Value | Positive Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0: one ratio | 38 | −13,579.23 | ω0 = 0.09246 | |||

| M3: discrete | 42 | −13,413.93 |

p0 = 0.14105, p1 = 0.62465, p2 = 0.23430, |

M0 vs. M3 | 0.00 | None |

|

ω0 = 0.01164, ω1 = 0.06928, ω2 = 0.25309 | ||||||

| M2a: selection | 41 | −13,554.18 |

p0 = 0.935245, p1 = 0.03719, p2 = 0.02757, |

|||

|

ω0 = 0.08829, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2 = 1.00000 | ||||||

| M1a: neutral | 39 | −13,554.18 | p0 = 0.93524, p1 = 0.06476, | M1a vs. M2a | 1.00 | None |

| ω0 = 0.08829, ω1 = 1.00000 | ||||||

| M8: beta and ω > 1 | 41 | −13,430.72 |

p0 = 0.99883, p = 1.12281, q = 9.15782, |

M7 vs. M8 | 0.9839 | None |

| p1 = 0.00117, ω = 1.00000 | ||||||

| M7: beta | 39 | −13,430.73 | p = 1.11747, q = 9.06492 | |||

| M8a: beta and ω = 1 | 40 | −13,419.70 |

p0 = 0.99999, p = 1.35368, q = 11.54435, |

M8a vs. M8 | 0.000002674 | None |

| p1 = 0.0000, ω = 1.00000 | ||||||

For the branch model (Table 4), 14 main clades of NtCCDs were defined as foreground branches. The results showed that all ω values were less than 1 for the 14 foreground branches (Figure 8), indicating that they were under purifying selection. We then applied the branch-site model, which accommodates heterogeneity among sites and can reflect divergent selective pressures. Parameter estimates under this model suggested that, when the ancestor branch of the tobacco CCD subfamily (labeled as i branch) was the foreground branch, a large set of sites (81.697%) evolved under strong purifying selection (ω = 0.063) and that a small set of sites (5.118%) evolved under neutral evolution (ω = 1); in addition, another small set of sites (13.185%) evolved under positive selective pressures (ω = 11.8) (Table 5). Using the Bayes empirical Bayes method, we identified seven codon sites with posterior probabilities ≥ 95% that evolved under positive selective pressure on the branch ancestral to the tobacco CCD subfamily (131K, 339I, 343A, 349G, 406F, 413Y, 533F, and NtCCD1a used as the amino acid reference). When the ancestor branch of CCD1 and CCD4 group genes (labeled as g branch) and the ancestor branch of CCD7, CCD8, and CCDL group genes (labeled as k branch) were the foreground branches, no codon sites with posterior probabilities ≥ 95% were identified under positive selective pressures.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates and likelihood values for NtCCDs using the branch model.

| Model | Np | Ln L | Estimates of Parameters | LRT p-Value | Positive Sites (BEB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 0 | 38 | −13579.23 | ω = 0.09246 | ||

| Two ratio branch a | 39 | −13575.32 | ω0 = 0.10005, ω1 = 0.04060 | 0.005 | None |

| Two ratio branch b | 39 | −13564.78 | ω0 = 0.10374, ω1 = 0.00918 | 0.000 | None |

| Two ratio branch c | 39 | −13574.47 | ω0 = 0.09358, ω1 = 0.00164 | 0.002 | None |

| Two ratio branch d | 39 | −13574.37 | ω0 = 0.09763, ω1 = 0.02200 | 0.002 | None |

| Two ratio branch e | 39 | −13574.07 | ω0 = 0.09443, ω1 = 0.00421 | 0.001 | None |

| Two ratio branch f | 39 | −13578.74 | ω0 = 0.09401, ω1 = 0.04312 | 0.321 | None |

| Two ratio branch g | 39 | −13577.44 | ω0 = 0.09348, ω1 = 0.00024 | 0.059 | None |

| Two ratio branch h | 39 | −13574.78 | ω0 = 0.09439, ω1 = 0.00432 | 0.003 | None |

| Two ratio branch i | 39 | −13572.92 | ω0 = 0.09489, ω1 = 0.00216 | 0.00 | None |

| Two ratio branch j | 39 | −13579.19 | ω0 = 0.09241, ω1 = 0.12516 | 0.772 | None |

| Two ratio branch k | 39 | −13578.89 | ω0 = 0.09278, ω1 = 0.00154 | 0.409 | None |

| Two ratio branch l | 39 | −13579.14 | ω0 = 0.09277, ω1 = 0.05689 | 0.662 | None |

| Two ratio branch m | 39 | −13578.69 | ω0 = 0.09311, ω1 = 0.00201 | 0.297 | None |

| Two ratio branch n | 39 | −13576.50 | ω0 = 0.09367, ω1 = 0.00833 | 0.019 | None |

Table 5.

Parameter estimates and likelihood values for NtCCDs, using the branch-site model.

| Model | Np | Ln L | Estimates of Parameters | LRT p-Value |

Positive Sites (BEB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A (Branch g) |

41 | −13551.77 |

p0 = 0.90022, p1 = 0.06108, p2a = 0.03624, p2b = 0.00246, ω0 = 0.08803, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2a = 999.00000, ω2b = 999.00000 |

0.03 | None |

| Model A Null (Branch g) |

40 | −13554.00 |

p0 = 0.86534, p1 = 0.05982, p2a = 0.07000, p2b =0.00484, ω0 = 0.08808, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2a = 1.00000, ω2b = 1.00000 |

Not Allowed | |

| Model A (Branch i) |

41 | −13545.47 |

p0 = 0.81697, p1 = 0.05118, p2a = 0.12408, p2b = 0.00777, ω0 = 0.08849, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2a = 11.81766, ω2b = 11.81766 |

0.01 | 131K *, 339I **, 343A *, 349G *, 406F *, 413Y *, 533F * |

| Model A Null (Branch i) |

40 | −13548.71 |

p0 = 0.79861, p1 = 0.05219, p2a = 0.14005, p2b = 0.00915, ω0 = 0.0867, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2a = 1.00000, ω2b = 1.00000 |

Not Allowed | |

| Model A (Branch k) |

41 | −13545.83 |

p0 = 0.79074, p1 = 0.04952, p2a = 0.15032, p2b = 0.00941, ω0 = 0.08852, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2a = 999.00000, ω2b = 999.00000 |

0.0009 | None |

| Model A Null (Branch g) |

40 | −13551.29 |

p0 = 0.77180, p1 = 0.05151, p2a = 0.16563, p2b = 0.01105, ω0 = 0.08705, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2a = 1.00000, ω2b = 1.00000 |

Not Allowed |

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. BEB: Bayes empirical Bayes.

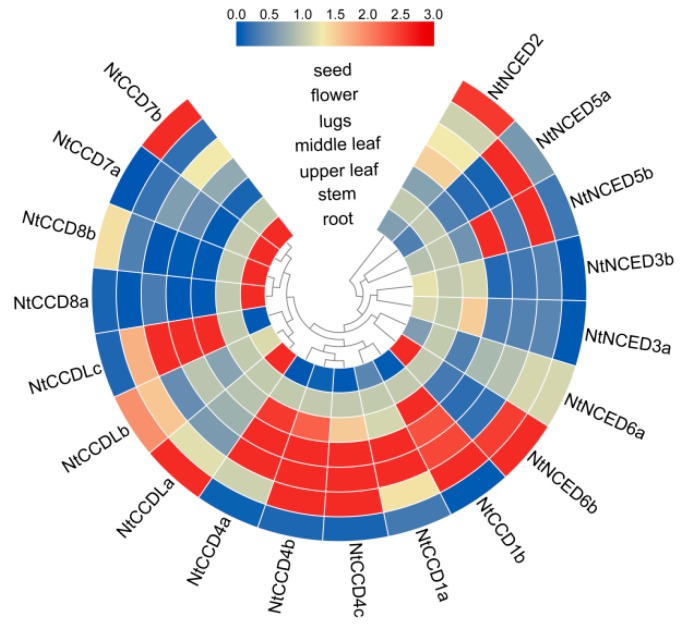

2.10. Expression Patterns of NtCCDs in Different Tissues

To elucidate the roles of NtCCD genes, the tissue-specific expression levels of CCD genes were analyzed, using the qRT-PCR method. Seven samples including root, stem, upper leaf, middle leaf, lugs, flower, and seeds were collected. The results showed that most NtCCD genes were expressed in the upper leaf, middle leaf, and lugs. Five genes (NtCCD1b, NtCCD4b, NtCCD4c, NtNCED5a, and NtNCED5b) were highly expressed in the flower (Figure 9, Supplementary Table S3). Six genes (NtCCD1a, NtCCD1b, NtCCD4a, NtCCD4b, NtCCD4c, and NtCCDLc) were highly expressed in middle leaves and lugs, followed by the upper leaves and flower. Six genes (NtCCD7a, NtCCD7b, NtCCD8a, NtCCD8b, NtNCED3a, and NtNCED3b) showed the highest expression in roots. In contrast, four genes (NtCCD7b, NtCCDLa, NtNCED2, and NtNCED6b) were highly expressed in the seed. These diverse expression levels could suggest that CCD family genes have functional importance in different tissues.

Figure 9.

Heat map representation displaying the expression patterns of NtCCDs genes in different tissues in tobacco. The gene expression levels in the seven tissues were explored by qRT-PCR and visualized by TBtools software. The scale bar above indicates relative expression level.

2.11. Gene Expression Analysis of Responses to Hormone Treatments and Abiotic Stresses

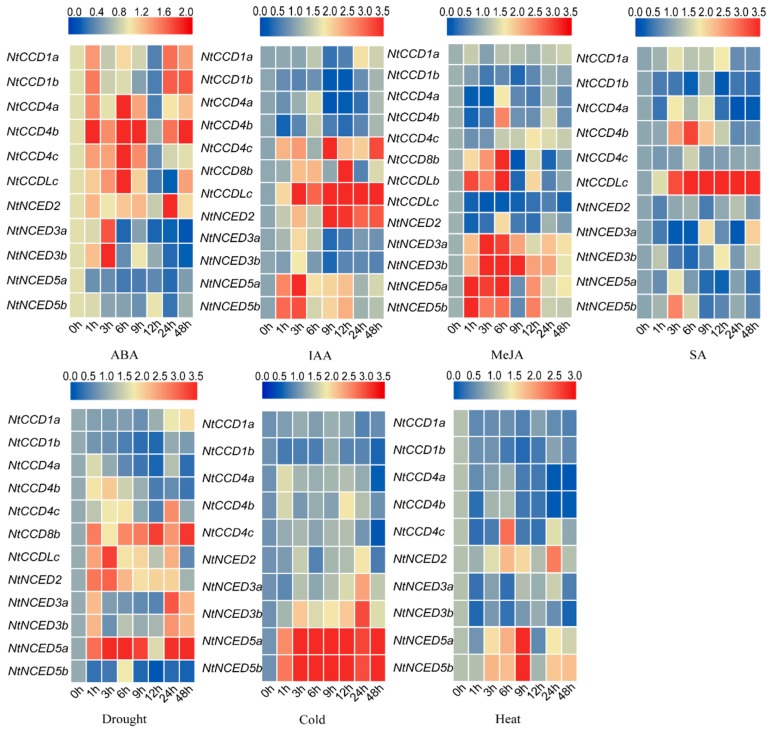

To investigate the effects of plant hormones and abiotic stresses on NtCCDs genes, the expression patterns of NtCCDs induced by the four hormones (ABA, MeJA, IAA, SA) associated with plant abiotic stresses (drought, cold, heat) were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Figure 10, Supplementary Table S4a–g). Of note, we did not detect the expression of NtCCD7a, NtCCD7b, NtCCD8a, NtCCDLa, NtNCED6a, and NtNCED6b in response to these treatments. In ABA-treated samples, the expression of most genes exhibited two peaks, showing an increasing pattern after ABA treatment and plateauing at 3–9 h, subsequently decreasing following the next peak. However, NtNCED5a and NtNCED5b exhibited decreased expression levels. The expression of other genes was not obviously changed. With respect to IAA treatment, the expression of NtCCD4c, NtCCD8b, NtCCDLc, NtNCED2, NtNCED5a, and NtNCED5b was obviously induced but reached their highest levels at different points. The expression of six genes (NtCCD8b, NtCCDLb, NtNCED3a, NtNCED3b, NtNCED5a, and NtNCED5b) was significantly increased after MeJA treatment, whereas expression of the remaining genes changed only slightly. Moreover, only the expression of NtCCD4c and NtCCDLc was induced remarkably by SA treatment. Regarding abiotic stresses, drought could evidently induce the highest increase in the expression of NtCCD8b, NtCCDLc, NtNCED3a, NtNCED3b, and NtNCED5a, followed by that of NtCCD4a, NtCCD4b, and NtCCD4c, and most genes showed a bimodal trend. The expression of NtNCED5a and NtNCED5b was significantly induced by cold treatment and reached a peak level at 9 h. NtNCED3a and NtNCED3b were also affected, especially at 24 h. Finally, for high-temperature stress, most genes were downregulated; however, the expression of NtCCD4c, NtNCED2, NtNCED5a, and NtNCED5b was significantly upregulated, particularly at 6 or 9 h after treatment.

Figure 10.

Heat map representation displaying the expression patterns of NtCCDs genes in the different hormone treatments (ABA, IAA, MeJA, SA) and abiotic stresses (drought, cold, heat). The gene expression levels were explored by qRT-PCR and visualized by TBtools software. The scale bars above indicate relative expression level.

3. Discussion

3.1. Basic Characteristics of NtCCD Genes Family

Tobacco is both an important model and economically significant crop worldwide. CCDs play an essential role in the synthesis of apocarotenoid flavor, aroma volatiles, and phytohormone ABA/SLs, which are important for plant development, crop quality, and stress responses. Due to their great significance, in this study, we identified 19, 11, and 10 CCD gene family members in N. tabacum, N. tomentosiformis, and N. sylvestris, respectively. Most previous reports have demonstrated that the CCD gene family can be divided into CCD and NCED subfamilies, including five (NCED and CCD1, 4, 7, and 8) or nine (CCD1, 4, 7, and 8; and NCED2, 3, 5, 6, and 9) groups in A. thaliana [4,10]. Moreover, a new group, CCDL, was found only in some species [11]. According to the phylogenetic tree in this research, we identified and classified CCD gene families in tobacco into two subfamilies (CCDs and NCEDs) and nine groups (CCD1, 4, 7, 8, and L; and NCED2, 3, 5, and 6). No NCED9 group was identified, because a corresponding ortholog from Arabidopsis was lacking. In addition, NCED subfamilies were found to be most closely related to CCD1 and CCD4 groups, whereas they had the most distant relationship with CCD7, CCD8, and CCDL groups. Tertiary structure prediction results also indicated that NtNCED proteins were structurally similar to NtCCD1 and NtCCD4 group proteins. In contrast, NtCCD7, NtCCD8, and NtCCDL were structurally more different, although all NtCCD family proteins had a conserved hydrophobic cavity composed mainly of β-sheets and a helix. Comprehensive analyses of chromosomal locations and gene duplication revealed that members in the same group were all located on different chromosomes, and, according to the phylogenetic tree, each originated from one ancestor of tetraploid tobacco, N. sylvestris or N. tomentosiformis. These results suggested that gene retention after WGD and chromosomal arrangements are responsible for expansion of the CCD gene family in tobacco. No tandem duplications were detected in this research; this outcome was inconsistent with previous reports on M. domestica [13].

Analyses of gene structures and motifs indicated that the numbers and positions of exons/introns and conserved motifs were usually similar in the same group. Intron numbers of all NtCCD genes ranged from 0 to 14, and motif numbers ranged from 7 to 14. The CCD1 group had the most introns and these genes are reported to be involved in the production of aromatic volatile compounds and pigmentation [19,21]. Meanwhile, the CCD4 group had only one intron, and it is involved in color formation, especially in flowers and fruits. CCD7 and CCD8 groups had five introns and harbored the fewest motifs, which may be involved in the biosynthesis of SL and related to branch growth development. Except for NtNCED6a and NtNCED6b, all NCED subfamily genes were intron-free but encoded more conserved motifs compared to that in the other groups, and this phenomenon is widespread in plants. Further, whether more motifs provide NCED proteins with more functions needs to be researched in the future. The absence of introns might be due to the loss of intron in the process of gene duplication. This intron-free structure of NCED genes is considered to be necessary for rapid and efficient synthesis of ABA and ABA-mediated stress response in plants, which is a result of a highly accurate posttranscriptional processing under stress [12]. The 3D structure prediction combined motif analysis and sequence alignment revealed that all CCD proteins contained four conserved iron-ligating histidine and three glutamate or aspartate residues required for enzyme activity, except for NtCCDLa and NtCCDLb. It is not known whether the lack of a conserved histidine in NtCCDLa and NtCCDLb affects enzyme activity and subsequently the function of the CCDL protein, considering that no CCDL functional or point mutations in these residues have been reported in related research. It would thus be helpful to clarify the function of the active site and CCDL genes, which could lead to novel insights for the CCD gene family.

3.2. Molecular Evolution of NtCCDs Genes in Tobacco

To gain new insight into the role of the CCD gene family, we evaluated possible selection pressures. The results of branch model analysis defined 14 main clades as foreground branches, which showed variable ω ratios among the groups; however, all ω values were less than 1, implying that purifying selection is the main driver of CCD evolution. Site models based on several paired comparisons (M0 vs. M3, M1a vs. M2a, M7 vs. M8, and M8a vs. M8) detected several sites of positive selection for all CCD groups. The results revealed that, although selective pressure varies among different CCD genes, there was no evidence of a strong role of positive selection in the evolution of CCD genes. This suggests that CCD sequences in tobacco plants are highly conserved, which might imply that CCD families have fulfilled certain requirements and that some of their functions are so important to tobacco that they have evolved with lower rates and cannot change optionally.

For most genes, positive selection often occurs at only a few loci of a specific pedigree. To detect this type of local interpolation of natural selection signals, positive selection tests based on the branch and site model are greatly limited. The branch-site model, which allows the ω parameter to differ between branches and sites at the same time, can detect the sites that endure positive selection on the branches specified in advance. The prespecified branch is called the foreground branch, whereas the other branches are the background branches. The model assumes that the ω parameters are different between sites and that some ω parameters of the sites are subjected to positive selection on the foreground branches. In this study, we also applied the branch-site model. When the ancestor branch of the tobacco CCD subfamily was the foreground branch, most sites (81.697%) evolved under strong purifying selection, and a few sites (13.185%) evolved under positive selective pressures (ω = 11.8). After BEB analysis, seven codon sites with posterior probabilities ≥ 95% were identified as evolving under positive selective pressures (131K, 339I, 343A, 349G, 406F, 413Y, 533F, and NtCCD1a used as an amino acid reference). Combining protein structure and positive selection analyses can help to explain Darwinian selection on branches and sites. As shown in the structural model of NtCCD1a (Figure 11), 406F is located within the conserved hydrophobic cavity, surrounded by four conserved iron-ligating histidines and three glutamate or aspartate residues required for enzyme activity. Other positive sites are located around these conserved activity sites. Among these, 339I and 343A are located on motif 3, in addition to 406F and 413Y on motif 4, which are the two conserved motifs that were contained by all CCD and NCED subfamily proteins. According to common opinion, positive selection might drive diversification functions and possess biological significance during species evolution. This study will provide useful information and new insights into the functional divergence of CCD and NCED subfamilies, which is worth further investigation.

Figure 11.

The predicted 3D structures and the positive sites of NtCCD1a (used as amino acid reference). The models were built with SWISS-MODEL and displayed with PyMOL software. The conserved four iron-ligating histidine (H) residues, and the conserved glutamates or aspartates (glycine in CCDL group) required for activity and positive sites were marked with yellow, blue, and red sphere, respectively.

3.3. Regulation of NtCCD Genes in Tobacco

The NtCCD promoters were found to contain many potential elements involved in light-responsiveness (GT1-motif, G-Box, ACE, Sp1, MRE), hormone stress (ABRE, TCA-element, SARE, CGTCA-motif, TGACG-motif, CGTCA-motif, TGACG-motif, AuxRR-core, TGA-element), and physiological stress (TC-rich repeats, MBS, LTR). These results indicated that the NtCCD genes might be involved in these processes. We ultimately tested the expression of these genes upon exposure by several hormone treatments and abiotic stresses.

CCD1 plays an important role in the production of apocarotenoid volatiles such as aroma and flavor substances [16,18]. Our results showed that NtCCD1 is expressed mainly in leaves and flowers. The expression of NtCCD1 can be induced by ABA and drought. CCD4 is mainly involved in color-, flavor-, and aroma-formation in fruit, flowers, and leaves [22,23]. Similar to NtCCD1, NtCCD4 was found to be highly responsive to ABA and dehydration stresses. This is consistent with a previous report [28]. NtCCD4b was also found to be markedly downregulated by MeJA and SA. Moreover, NtCCD4c was highly responsive to IAA. This illustrated that even genes of the same group might be affected by different factors and exhibit diverse functions. CCD7 and CCD8 are mainly involved in the biosynthesis of strigolactone, which controls the shoot branch and regulates rhizosphere signaling and response to stresses in plants [29,31,32]. Tissue-specific expression analysis showed that NtCCD7 and NtCCD8 exhibited the highest expression levels in roots. Moreover, no expression was detected in response to most treatments, except NtCCD8b was induced by IAA, MeJA, and drought. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that these genes were found to be expressed mainly in roots, but we collected samples only from leaves. Regarding the CCDL group, no research has been performed on the function of these genes. NtCCDLa and NtCCDLb were found to be expressed mainly in roots and seeds, whereas NtCCDLc was mainly localized to leaves. NtCCDLc was strongly induced by ABA, IAA, SA, and drought, but was inhibited by MeJA. In contrast, NtCCDLb was strongly induced only by MeJA. Meanwhile, NtCCDLa was scarcely expressed in response to all treatments.

The NCED subfamily is believed to regulate an important rate-limiting step in the synthesis of ABA [33,34]. In this study, NtNCED2, 3, 5, and 6 were predominantly expressed in different tissues. NtNCED2 was highly expressed in seeds and could be upregulated by ABA, IAA, drought, and heat. NtNCED3 was expressed mainly in roots and upper leaves and was upregulated by ABA, MeJA, drought, and cold. Our previous research on NtNCED3, as well as a report on A. thaliana, demonstrated that NCED3 is especially indispensable for the biosynthesis of ABA and can affect the growth of plants [39]. In contrast, ABA can be induced by abiotic stresses such as drought, cold, and heat, consistent with the upregulation expression of NtNCED3. NtNCED5a was found to be expressed mainly in flowers, whereas NtNCED5b was expressed in flowers and in middle leaves. IAA, MeJA, cold, and heat were also found to upregulate the expression of NtNCED5a and NtNCED5b. In addition, NtNCED5a was significantly induced by drought. Taken together, our results provide helpful information for further studies on the roles of NtCCDs, but more efforts are needed to clarify their diverse function.

We also searched the potential miRNA-target sites in the NtCCD transcripts. The identification of miRNA-target sites can provide clues into the biological functions of miRNAs/target genes during plant development and stress adaptation, and help to better understand functions and regulatory mechanisms. Seven miRNAs from five families in five NtCCD family genes were identified. Former research has shown that nta-miR6164a/b and nta-miR319/159 are related to the regulation of signal transduction, protein phosphorylation, cell differentiation, and virus infection [45,46]. Among plants, these miRNA families are usually highly conserved. However, this requires further verification in future studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification and Characterization of CCD

To perform genome-wide identification and obtain sequences of the CCD gene family in three Nicotiana species, nine published AtCCD sequences of A. thaliana were first downloaded from TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org). Then, using AtCCDs as queries, a blast search of tobacco genome sequences was performed. The CCD sequences of N. tabacum, N. sylvestris, N. tomentosiformis, and other species, including S. lycopersicum and C. annuum, were downloaded from China tobacco genome annotation project [restricted] and Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/). BLASTN and BLASTP programs were carried out by using default parameters, respectively. To further confirm the CCD family members, the CCD proteins were predicted by Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/search) and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) databases. The number of amino acids, Mws, and pIs of CCD proteins were calculated, using the online software ExPASy-ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/).

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of CCD Proteins and Gene Nomenclature

The identified CCD proteins were aligned by using ClustalW. The phylogenetic tree of the CCD family was generated by using the neighbor-joining method, with 1000 bootstrap replicates in Phylip3.69 based on the Jones–Taylor–Thornton (JTT) matrix-based model. Genes that had been reported previously were named accordingly [9,11,43], and others were named according to their homologies to those of Arabidopsis, S. lycopersicum, and C. annuum NCED and CCD subfamily genes in the phylogenetic tree, based on the species abbreviation.

4.3. Gene Structures and Conserved-Motif Prediction

Exon–intron structures of CCDs were predicted by using the online software Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (GSDS 2.0) (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/, Peking University, Beijing, China) [47]. The conserved motifs in the CCD protein sequences were firstly identified by the online software MEME (Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation, http://meme-suite.org, developed and maintained by University of Nevada, Nevada, USA, and The University Of Queensland, Queensland, Australia, in addition to University of Washington, WA, USA) [48], using the following parameters: the optimum motif width was set from 6 to 200 and 15 as the maximum number of motifs. The discovered motifs were then annotated, using the Pfam program.

4.4. Three-Dimensional (3D) Structure Modeling of CCD Family Proteins

The 3D structures of CCD family proteins were computer-modeled by the SWISS-MODEL program. The models were displayed by PyMOL software (DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA, USA).

4.5. Chromosomal Locations and Gene Duplication Analysis of CCD Genes in Tobacco

The physical positions of NtCCDs genes identified in tobacco were mapped to the chromosomes with the software MapGene2Chrome V2 (http://mg2c.iask.in/mg2c_v2.0/, Tobacco Research Institute of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Qingdao, China), and they were used to describe the locations of CCD genes. For gene duplication analysis, the collinearity relationships between CCD homologs were verified and visualized using the Circos tool in TBtools software (South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China) [49].

4.6. Subcellular Localization

The ChloroP 1.1 Server program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/, DTU Health Tech, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to predict the cTP of protein sequences. N-terminal sorting signals of the CCD proteins were also investigated, using the online software iPSORT (http://ipsort.hgc.jp/, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). The subcellular localizations of all CCD proteins were then predicted by using the online ExPASy tools Plant-mPloc (https://www.psort.org/, Simon Fraser University, BC, Canada) and ProtComp (http://linux1.softberry.com/all.htm, Softberry, Inc, Mount Kisco, NY, USA).

For experimental verification, the full length of NtCCD1a was amplified by specific primers, using the cDNA from young leaves of Nicotiana tabacum L. (Honghua Dajinyuan). The PCR products were linked with pBWA (V) HS-ccdb-GLosgfp vector to generate vector pBWA (V) HS-CCD1a-GFP fused with the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene. NtCCD1a fused with nuclear localization signal (NLS) protein marker was then cloned into pBWA (V) HS-ccdb-GLosgfp vector to generate the pBWA (V) HS-CCD1a-NLS fusion protein as a nuclear-anchored marker vector. The sequence of NLS was MDPKKKRKV in this study. Positive clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing and transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (GV3101) by electrotransformation, and then injected into the lower epidermis of tobacco leaves from 30-day-old plants. A corresponding empty vector was considered as the control. After two days of cultivation in low light, the localization of fluorescence signals was observed by using laser confocal microscope (Nikon C2-ER, Tokyo, Japan).

4.7. MiRNA Target Sites and Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements Prediction

CCDs were submitted to the online tool psRNATarget (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/, The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation, Ardmore, OK, USA) for predicting miRNA’s target sites, using default settings and threshold. The promoter regions (2000 bp upstream of ATG) of CCD family genes were retrieved from the China tobacco database and were searched for identifying various cis-regulatory elements by the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/).

4.8. Molecular Evolution of CCD Genes in Tobacco

The sequences of NtCCD genes were aligned based on codons, using ClustalW codons in the MEGA7 program (Tokyo Metropolitan University, Tokyo, Japan). To explore selective pressure between NtCCD gene sequences, after the removal of gaps, we performed strict statistical analysis, using the software EasyCodeML1.2 (Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China) [50]. The site model, branch model, and branch-site model were used based on the Preset Mode. The LRT tests whether the selected model is significantly better than the null model.

4.9. Plant Materials and Treatments

Nicotiana tabacum L. (Honghua Dajinyuan) was used to analyze the expression of NtCCD genes. Tobacco seeds were germinated and cultured by using a floating seedling production system under normal conditions (28 °C, 14 h light, 10 h dark). Tobacco was grown in the same environment, and stress treatments were applied until three true leaves appeared. Different tissues (root, stem, upper leaf, middle leaf, lugs, flower, and seed) were also collected, in order to analyze NtCCD gene expression at the flowering stage.

For drought stress, seedlings were cultivated in a solution containing 20% (w/v) polyethylene (PEG) 6000 for 48 h. For low- and high-temperature treatment, seedlings were kept at 4 and 42 °C, respectively, in illuminated incubators, for 48 h. For hormone treatments, seedlings were sprayed with 100 µmol of ABA, MeJA, or indoleacetic acid (IAA) or 1 mmol of salicylic acid (SA) for 48 h. All true leaves were sampled at 0 (control), 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 48 h, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C, prior to RNA extraction. Three biological replicates were performed for each sample.

4.10. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative Reverse-Transcription PCR

Total RNAs from different tissues above and under different stress treatments were extracted by using Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (FOREGENE, Chengdu, China). HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used for reverse transcription. The expression of CCD genes was tested by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). The primers of CCD genes used for the qRT-PCR were shown in Table S5. The PCR reaction mixtures contained 1 μL of cDNA, 5 μL of AceQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, China), 0.2 μL of each of forward/reverse primers, and 3.6 μL of double-distilled nuclease-free water. Reactions were run in a 96-well optical plate (Eppendorf, Saxony, Germany) at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and melting curve (95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, melting for 20 m, 95 °C for 15 s). Each sample was analyzed with three technical replicates. Melting curve analysis was conducted in order to verify the specificity of the primers. The mRNA levels of CCDs were normalized to L25, and the method of 2−ΔΔCt was used to calculate the expression of CCD genes [51].

5. Conclusions

In this study, 19 NtCCD gene family members in N. tabacum, 11 members in N. tomentosiformis, and 10 members in N. sylvestris were finally identified. According to the phylogenetic tree, they were classified into two subfamilies (CCDs and NCEDs) and nine groups (CCD1, 4, 7, 8, and L; NCED2, 3, 5, and 6). Moreover, members in the same group were all located on different chromosomes. Gene structures, conserved motifs, and tertiary structures were usually similar in the same group. Subcellular localization results predicted that CCD family genes are cytoplasmic and plastid-localized. Transient expression via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation confirmed this prediction. Evolutionary analysis further showed that the NtCCD genes were expanded, and no tandem duplication events during evolution were predicted. Analysis of molecular evolution demonstrated that purifying selection dominated the evolution of tobacco CCD families. However, seven positive sites were identified on the ancestor branch of the tobacco CCD subfamily. The expression of NtCCD genes was also found to be tissue-specific, and miRNA target-site prediction analysis identified seven miRNAs from five families in the five NtCCD family genes. NtCCD promoters were also found to contain many potential cis-acting elements involved in light-responsiveness, hormone stress, and physiological stress. The expression pattern of NtCCDs in response to several hormone treatments and abiotic stresses were detected. These results implied that NtCCDs play important roles in responses to different stresses, pigmentation, photosynthesis, and photoprotection. Our previous research showed that RNA interference of one of the NtCCDs family gene NtNCED3 could impair plant growth, causing a stunted phenotype by inhibiting root development and reducing drought tolerance through ABA feedback regulation in Nicotiana tabacum [41]. This study will provide valuable clues for future functional studies of CCD genes, but more efforts are needed to determine their detailed effects of ABA/SLs and different carotenoid metabolites on tobacco growth, development, and stress tolerance.

Abbreviations

| CCD | Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase |

| NCED | 9-Cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| SL | Strigolactone |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| Mw | Molecular weight |

| pI | Isoelectric point |

| ACE | Cis-acting element involved in light responsiveness |

| G-Box | Cis-acting regulatory element involved in light responsiveness |

| MRE | MYB binding site involved in light responsiveness |

| Sp1 | Light responsive element |

| GT1-motif | Light responsive element |

| CGTCA-motif | Cis-acting regulatory element involved in the MeJA-responsiveness |

| TGACG-motif | Cis-acting regulatory element involved in the MeJA-responsiveness |

| P-box | Gibberellin-responsive element |

| SARE | Cis-acting element involved in salicylic acid responsiveness |

| TCA-element | Cis-acting element involved in salicylic acid responsiveness |

| ABRE | Cis-acting element involved in the abscisic acid responsiveness |

| AuxRR-core | Cis-acting regulatory element involved in auxin responsiveness |

| TATC-box | Cis-acting element involved in gibberellin-responsiveness |

| TGA-element | Auxin-responsive element |

| GARE-motif | Gibberellin-responsive element |

| TC-rich repeats | Cis-acting element involved in defense and stress responsiveness |

| LTR | Cis-acting element involved in low-temperature responsiveness |

| MBS | MYB binding site involved in drought-inducibility |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/22/5796/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, and writing—review and editing, Y.Y.; software and writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z.; analyzed data, Q.L. and P.L.; investigation and data curation, S.Z. and C.L.; resources, J.J. and P.C.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Scientific Research Foundation of the Higher Education Institutions of Henan Province (Grant No. 18A180016) and Henan provincial key science and technology research projects (Grant No. 182102110315).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Henan Agricultural University and Zhengzhou Tobacco Research Institute of CNTC had no conflicts of interest. Zhengzhou Tobacco Research Institute of CNTC had no role in the design of the study and in the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ahrazem O., Gomez-Gomez L., Rodrigo M.J., Avalos J., Limon M.C. Carotenoid Cleavage Oxygenases from Microbes and Photosynthetic Organisms: Features and Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1781. doi: 10.3390/ijms17111781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohmiya A. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases and their apocarotenoid products in plants. Plant Biotechnol. 2009;26:351–358. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.26.351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hou X., Rivers J., Leon P., McQuinn R.P., Pogson B.J. Synthesis and Function of Apocarotenoid Signals in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:792–803. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter M.H., Floss D.S., Strack D. Apocarotenoids: Hormones, mycorrhizal metabolites and aroma volatiles. Planta. 2010;232:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McQuinn R.P., Giovannoni J.J., Pogson B.J. More than meets the eye: From carotenoid biosynthesis, to new insights into apocarotenoid signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015;27:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma G., Zhang L., Matsuta A., Matsutani K., Yamawaki K., Yahata M., Wahyudi A., Motohashi R., Kato M. Enzymatic formation of β-citraurin from β-cryptoxanthin and Zeaxanthin by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase4 in the flavedo of citrus fruit. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:682–695. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.223297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang F.C., Molnar P., Schwab W. Cloning and functional characterization of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:3011–3022. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz S.H., Tan B.C., Gage D.A., Zeevaart J.A., McCarty D.R. Specific Oxidative Cleavage of Carotenoids by VP14 of Maize. Science. 1997;276:1872–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan B.C., Joseph L.M., Deng W.T., Liu L.J., Li Q.B., Cline K., McCarty D.R. Molecular characterization of the Arabidopsis 9-cis epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene family. Plant J. 2003;35:44–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang R.K., Wang C.E., Fei Y.Y., Gai J.Y., Zhao T.J. Genome-wide identification and transcription analysis of soybean carotenoid oxygenase genes during abiotic stress treatments. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;40:4737–4745. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2570-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Y.P., Wan H.J., Wu Z.M., Wang R.Q., Ruan M.Y., Ye Q.J., Li Z.M., Zhou G.Z., Yao Z.P., Yang Y.J. A Comprehensive Analysis of Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenases Genes in Solanum Lycopersicum. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2016;34:512–523. doi: 10.1007/s11105-015-0943-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Ding G.J., Gu T.T., Ding J., Li Y. Bioinformatic and expression analyses on carotenoid dioxygenase genes in fruit development and abiotic stress responses in Fragaria vesca. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2017;292:895–907. doi: 10.1007/s00438-017-1321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H.F., Zuo X.Y., Shao H.X., Fan S., Ma J.J., Zhang D., Zhao C.P., Yan X.Y., Liu X.J., Han M.Y. Genome-wide analysis of carotenoid cleavage oxygenase genes and their responses to various phytohormones and abiotic stresses in apple (Malus domestica) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;123:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahrazem O., Rubio-Moraga A., Berman J., Capell T., Christou P., Zhu C., Gomez-Gomez L. The carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase CCD2 catalysing the synthesis of crocetin in spring crocuses and saffron is a plastidial enzyme. New Phytol. 2016;209:650–663. doi: 10.1111/nph.13609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahrazem O., Rubio-Moraga A., Argandona-Picazo J., Castillo R., Gomez-Gomez L. Intron retention and rhythmic diel pattern regulation of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 2 during crocetin biosynthesis in saffron. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016;91:355–374. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0473-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Z., Hans J., Walter M.H., Matusova R., Beekwilder J., Verstappen F.W., Ming Z., van Echtelt E., Strack D., Bisseling T., et al. Cloning and characterisation of a maize carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (ZmCCD1) and its involvement in the biosynthesis of apocarotenoids with various roles in mutualistic and parasitic interactions. Planta. 2008;228:789–801. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0781-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu J., Ai G., Shen D.Y., Chai C.Y., Jia Y.L., Liu W.J., Dou D.L. Bioinformatical analysis and prediction of Nicotiana benthamiana bHLH transcription factors in Phytophthora parasitica resistance. Genomics. 2019;111:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilg A., Beyer P., Al-Babili S. Characterization of the rice carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase1 reveals a novel route for geranial biosynthesis. FEBS J. 2009;276:736–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simkin A.J., Underwood B.A., Auldridge M., Loucas H.M., Shibuya K., Schmelz E., Clark D.G., Klee H.J. Circadian regulation of the PhCCD1 carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase controls emission of β-ionone, a fragrance volatile of petunia flowers. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3504–3514. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.049718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibdah M., Azulay Y., Portnoy V., Wasserman B., Bar E., Meir A., Burger Y., Hirschberg J., Schaffer A.A., Katzir N., et al. Functional characterization of CmCCD1, a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase from melon. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simkin A.J., Schwartz S.H., Auldridge M., Taylor M.G., Klee H.J. The tomato carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 genes contribute to the formation of the flavor volatiles β-ionone, pseudoionone, and geranylacetone. Plant J. 2004;40:882–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe K., Oda-Yamamizo C., Sage-Ono K., Ohmiya A., Ono M. Alteration of flower colour in Ipomoea nil through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4. Transgenic Res. 2018;27:25–38. doi: 10.1007/s11248-017-0051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song M.H., Lim S.H., Kim J.K., Jung E.S., John K.M.M., You M.K., Ahn S.N., Lee C.H., Ha S.H. In planta cleavage of carotenoids by Arabidopsis carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 in transgenic rice plants. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2016;10:291–300. doi: 10.1007/s11816-016-0405-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adami M., De Franceschi P., Brandi F., Liverani A., Giovannini D., Rosati C., Dondini L., Tartarini S. Identifying a Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase (ccd4) Gene Controlling Yellow/White Fruit Flesh Color of Peach. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;31:1166–1175. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0628-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohmiya A., Kishimoto S., Aida R., Yoshioka S., Sumitomo K. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CmCCD4a) contributes to white color formation in chrysanthemum petals. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1193–1201. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.087130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruno M., Beyer P., Al-Babili S. The potato carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 catalyzes a single cleavage of β-ionone ring-containing carotenes and non-epoxidated xanthophylls. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015;572:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko M.R., Song M.H., Kim J.K., Baek S.A., You M.K., Lim S.H., Ha S.H. RNAi-mediated suppression of three carotenoid-cleavage dioxygenase genes, OsCCD1, 4a, and 4b, increases carotenoid content in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69:5105–5116. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba S.A., Jain D., Abbas N., Ashraf N. Overexpression of Crocus carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase, CsCCD4b, in Arabidopsis imparts tolerance to dehydration, salt and oxidative stresses by modulating ROS machinery. J. Plant Physiol. 2015;189:114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butt H., Jamil M., Wang J.Y., Al-Babili S., Mahfouz M. Engineering plant architecture via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated alteration of strigolactone biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz S.H., Qing X.Q., Loewen M.C. The Biochemical Characterization of Two Carotenoid Cleavage Enzymes from Arabidopsis indicates that a Carotenoid-Derived Compound Inhibits Lateral Branching. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46940–46945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasegawa S., Tsutsumi T., Fukushima S., Okabe Y., Saito J., Katayama M., Shindo M., Yamada Y., Shimomura K., Yoneyama K., et al. Low Infection of Phelipanche aegyptiaca in Micro-Tom Mutants Deficient in CAROTENOIDCLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE 8. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2645. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ha C.V., Leyva-Gonzalez M.A., Osakabe Y., Tran U.T., Nishiyama R., Watanabe Y., Tanaka M., Seki M., Yamaguchi S., Dong N.V., et al. Positive regulatory role of strigolactone in plant responses to drought and salt stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. USA. 2013;111:851–856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322135111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auldridge M.E., McCarty D.R., Klee H.J. Plant carotenoid cleavage oxygenases and their apocarotenoid products. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006;9:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacqueline T.C., Jan A.D.Z. Characterization of the 9-Cis-Epoxycarotenoid Dioxygenase Gene Family and the Regulation of Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis in Avocado. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:343–353. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo P., Shen Y.X., Jin S.X., Huang S.S., Cheng X., Wang Z., Li P.H., Zhao J., Bao M.Z., Ning G.G. Overexpression of Rosa rugosa anthocyanidin reductase enhances tobacco tolerance to abiotic stress through increased ROS scavenging and modulation of ABA signaling. Plant Sci. 2016;245:35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao G.G., Zhuo C.L., Qian C.M., Xiao T., Guo Z.F., Lu S.Y. Co-expression of NCED and ALO improves vitamin C level and tolerance to drought and chilling in transgenic tobacco and stylo plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;14:206–214. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iuchi S., Kobayashi M., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. A Stress-Inducible Gene for 9-cis-Epoxycarotenoid Dioxygenase Involved in Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis under Water Stress in Drought-Tolerant Cowpea. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:553–562. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He R.R., Zhuang Y., Cai Y.M., Agüero C.B., Liu S.L., Wu J., Deng S.H., Walker M.A., Lu J., Zhang Y.L. Overexpression of 9-cis-Epoxycarotenoid Dioxygenase Cisgene in Grapevine Increases Drought Tolerance and Results in Pleiotropic Effects. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]