Abstract

Objective: This meta-analysis aimed to estimate the global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents. Methods: A systematic search for relevant articles published between 1989 to 2018 was performed in multiple electronic databases. The aggregate 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm, and non-suicidal self-injury were calculated based on the random-effects model. Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the prevalence according to school attendance and geographical regions. Results: A total of 686,672 children and adolescents were included. The aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts was 6% (95% CI: 4.7–7.7%) and 4.5% (95% CI: 3.4–5.9%) respectively. The aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal plan was 9.9% (95% CI: 5.5–17%) and 7.5% (95% CI: 4.5–12.1%) respectively. The aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation was 18% (95% CI: 14.2–22.7%) and 14.2% (95% CI: 11.6–17.3%) respectively. The aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury was 22.1% (95% CI: 16.9–28.4%) and 19.5% (95% CI: 13.3–27.6%) respectively. The aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm was 13.7% (95% CI: 11.0–17.0%) and 14.2% (95% CI: 10.1–19.5%) respectively. Subgroup analyses showed that full-time school attendance, non-Western countries, low and middle-income countries, and geographical locations might contribute to the higher aggregate prevalence of suicidal behaviors, deliberate self-harm, and non-suicidal self-injury. Conclusions: This meta-analysis found that non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and deliberate self-harm were the three most common suicidal and self-harm behaviors in children and adolescents.

Keywords: adolescents, children, meta-analysis, non-suicidal self-injury, deliberate self-harm, suicide

1. Introduction

During the past 30 years, suicide has become a severe cause of mortality across all ages in the world. In 2015, the number of suicide deaths worldwide was estimated to be 788,000 [1], with a global average of 10.7 per 100,000. Suicide was ranked second as a cause of mortality amongst those aged 15–29 years old globally [2], making it a global public health concern. Suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury are important antecedents of suicide in children and adolescents [2]. Suicidal behaviors involve suicidal ideation, planning for suicide and suicide attempts [3]. Self-harm behavior is defined here as an act of intentionally causing harm to own self, irrespective of the type, motive or suicidal intent [2]. Non-suicidal self-injury is defined as deliberate direct destruction or alteration of body tissue without conscious suicidal intent [4]. Deliberate self-harm is an encompassing term for self-injurious behavior, both with and without suicidal intent that has a non-fatal outcome [5]. Non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm are common in young people who will have borderline personality traits or disorder [6]. Non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm have been known to predict future suicide attempts [7].

There are potential factors that affect the global prevalence of suicidal and self-harm behavior in children and adolescents. From cross-cultural perspectives, there are ethnic differences in risk factors of suicide attempts [8,9]. In Western countries like Canada, suicide accounts for 10% of deaths in children aged 10 to 14 years and for 23% of deaths in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years [10]. In New Zealand, children and adolescents from the lowest socio-economic status were found to be 31 times more likely to attempt suicide compared to individuals in the higher socio-economic status [11]. In Asia, relationship issues, academic and environmental stressors are common precipitants for suicide attempts among young people [12]. In Singapore, a peak in suicide attempts has been observed in adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 24 years old [12]. Cross-cultural studies found that self-harm behaviors amongst eighth-graders in Hong Kong (23.5%) were less frequent compared to those in the United States (32%) [13]. The lower self-harm rate in Hong Kong adolescents was attributed to cultural differences between the Eastern and Western cultures, with a stronger emphasis on family structures and rules in Asian culture [13]. A meta-analysis is required to study cross-cultural perspectives of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm, and non-suicidal self-injury among young people in different countries in a systematic manner.

From a gender perspective, Lewinsohn et al. found female adolescents to have a significantly higher risk of suicide attempts compared to male counterparts, with the differences between genders diminishing as participants increased with age [14]. Furthermore, gender was found to predict lethality in suicide attempts as more males than females made attempts with high perceived lethality and medical lethality [15]. Youth who experienced difficulty in school were at risk for suicide [16]. However, there is little published information specific to the relationship between school attendance, suicidal behaviors, deliberate self-harm, and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents.

Despite the seriousness and scope of the problem, little is known about the global prevalence of suicidal and self-harm behaviors in children and adolescents in the past 30 years. Further research is required to compare the prevalence of suicidal, and self-harm behavior among children and adolescents from different geographical regions as contextual differences (e.g., exposure to adversity) across countries may affect prevalence estimates. Given the above findings and observations, we aimed to conduct a meta-analyze to estimate the global 12-month and lifetime prevalence of adolescents having a history of suicide attempts, suicide plans, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, and deliberate self-harm between 1989 to 2018.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

During the past thirty years, the advent of computer technology, the Internet, and the widespread use of social media have affected suicidal behaviors, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in young people. Many young people report that computers and the Internet facilitate their communication with peers [17]. The effect of social media on suicidal behaviors, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury is still under evaluation. Some studies suggested that social media use has led to the growth of suicide clusters [18], while others showed that it had a positive impact on the prevention of suicide given the myriad of support platforms for the children and adolescents at risk [19]. Given the above findings and observations, this meta-analysis focused from 1989 to 2018.

This study was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses PRISMA) guidelines. A systematic search was performed with dates covered from 1 January 1989 to 31 December 2018, using a combination of search terms (* indicates truncation): ‘suicid */suicide attempt *’, ‘self harm’ or ’self-harm’,’self injury’ or ’self-injury’, ‘adolescent’, ’youth’, ’young’, ’child *’,’teen *’,’student *’,’school *’ and ‘prevalence’. Electronic databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Embase were utilized. The reference lists of reviews, reports, and other relevant articles were also examined to identify additional studies.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Two authors (K.-S.L. and R.C.H.) independently identified the eligibility of studies. The studies included in this review must fulfil the following inclusion criteria: (1) the study provided cross-sectional data on the lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm or non-suicidal self-injury; (2) the study population was children or adolescents and (3) a clear definition of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm or non-suicidal self-injury were reported. Any study that did not meet the aforementioned inclusion criteria were excluded. Any discrepancies between the two authors were reviewed by another author (C.S.H.) and resolved with consensus.

2.3. Data Extraction

Two authors (K.-S.L. and R.C.H.) independently extracted the following data from each eligible study: first author, year of publication, the country where the study was conducted, number of participants with suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm or non-suicidal self-injury, total sample size, mean age of participants, proportion of female gender and school attendance. Any disagreements between the two authors were resolved via discussion with a third author (C.S.H.). The three authors involved in this process were trained in medicine and psychiatry.

2.4. Study Outcomes

A suicide attempt is defined as an act in which an adolescent tries to end his or her life but survives [20]. A suicide plan is a proposed plan of carrying out a suicidal act that may lead to potential death [21]. Suicidal ideation is defined as any self-reported thoughts of engaging in suicide-related behavior [22]. Non-suicidal self-injury is defined as the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially sanctioned, such as cutting, burning, and biting [23]. Deliberate self-harm is defined as self-injurious behaviors with and without suicidal intent and that have non-fatal outcomes. The 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts, suicide plans, suicide ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, and deliberate self-harm were extracted from each study, which met inclusion criteria.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in Comprehensive Meta-analysis statistical software version 3.0 (BioStat Solutions, Inc, Frederick, MD, USA). The aggregate prevalence was calculated based on the random-effects model. The random-effects model was used as it assumes varying effect sizes between studies, because of differing study design and study population [24,25]. A forest plot was then constructed and reported the aggregate prevalence, 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value based on the method adopted by previous meta-analysis on prevalence [26,27]. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. The statistic was used to assess the between-study heterogeneity [28], which describes the percentage of variance on the basis of real differences in study effects. value of 25% was considered low, 50% moderate and 75% substantial [29].

Publication bias was assessed with the utilization of Egger’s regression [25]. A p-values of 0.05 or less was used as the cut off for the presence of statistically significant publication bias [30]. The presence of publication bias was then further investigated using both the standard and Orwin’s fail-safe N tests to provide an estimated number of additional studies required to make the eventual effect size insignificant [31]. Meta-regression analyses with a mixed-effect model were performed to identify the effects of potential moderators on the overall heterogeneity. Potential moderators include mean age of sample and proportion of female gender. Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the aggregate prevalence of each study outcome with regards to school attendance and study location. The definitions of developing and developed countries were based on Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use developed by the United Nations [32].

3. Results

3.1. Selection Results and Study Characteristics

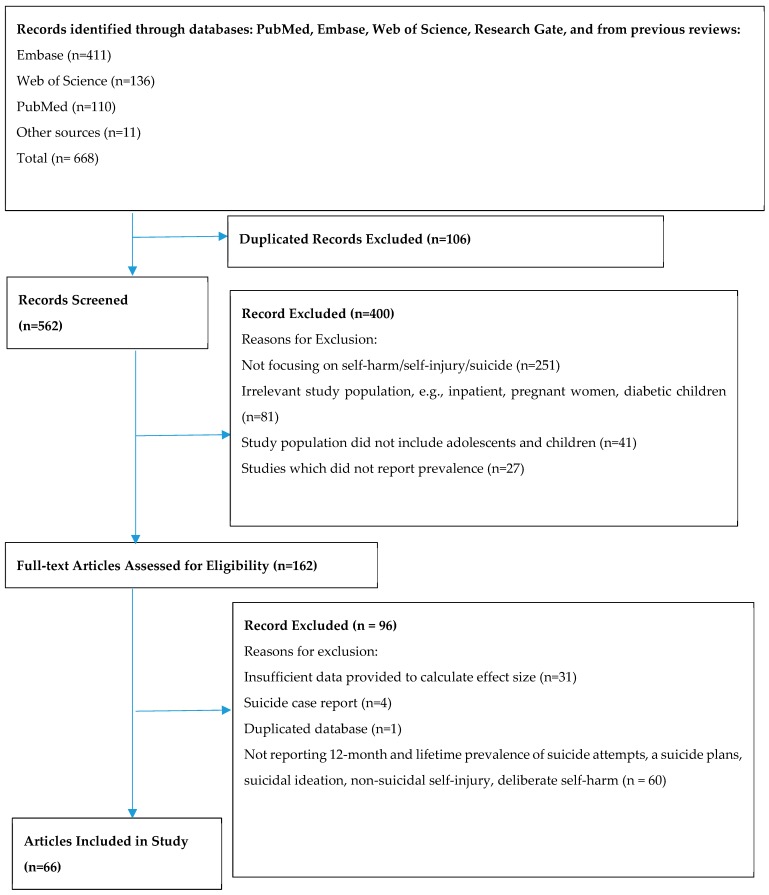

A total of 668 potentially relevant citations were gathered after an extensive literature search was performed on the databases listed in Figure 1. A total of 106 studies were found to be duplicated. Of the remaining 562 studies for which titles and abstracts were screened, 400 were excluded. The final 162 studies were then reviewed in full, of which 96 were excluded, leaving 66 studies that met the inclusion criteria to be used in this meta-analysis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—chart depicting the detailed process of paper selection can be seen in Figure 1. The 66 studies included in the meta-analysis yields a total population of 686,672 study participants. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 1.

Process of systematic selection using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Studies Included in This Meta-Analysis.

| First Author | Year | Study Location | Sample Size | Mean Age | Proportion of Female Gender | Prevalence of Suicide Attempts | Prevalence of Suicide Plans | Prevalence of Suicide Ideation | Prevalence of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury | Prevalence of Deliberate Self-Harm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abell [33] | 2012 | Jamaica | 2997 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 12M:0.097 | NA | NA |

| Altangerel [34] | 2014 | Mongolian | 5191 | NA | 0.567 | 12M: 0.086 | 12M:0.125 | 12M: 0.196 | NA | NA |

| Asante [35] | 2017 | Ghana | 1984 | NA | 0.458 | 12M: 0.221 | 12M:0.221 | 12M: 0.181 | NA | NA |

| Atlam [36] | 2017 | Turkey | 2973 | NA | 0.548 | NA | LT: 0.248 | NA | NA | LT: 0.154 |

| Baetens [37] | 2011 | Belgium | 1417 | 15.13 | 0.814 | NA | NA | LT: 0.605 | LT: 0.216 | NA |

| Begum [38] | 2017 | Bangladesh | 2476 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT:0.05 | NA | NA |

| Benjet [39] | 2017 | Mexico | 1071 | NA | 0.57 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.186 | NA |

| Borges [40] | 2011 | United States | 1004 | NA | 0.56 | NA | NA | 12M: | NA | 12M: 0.076 |

| Brunner [41] | 2007 | Germany | 5759 | 14.9 | 0.498 | LT: 0.079 | LT: 0.065 | LT: 0.144 | NA | LT: 0.149 |

| Brunner [42] | 2014 | Various European countries | 12073 | 14.9 | 0.556 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT:0.275 |

| Calvete [43] | 2015 | Spain | 1864 | 15.32 | 0.514 | NA | NA | NA | 12M: 0.536 | NA |

| Carvalho [44] | 2017 | Brazil | 1763 | 16.75 | 0.53 | NA | NA | LT: 0.22 | LT:0296 | NA |

| Cerutti [45] | 2011 | Italy | 234 | 16.47 | 0.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.419 |

| Chan [46] | 2008 | Hong Kong | 10239 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.291 | NA | NA |

| Chan [46] | 2008 | Hong Kong | 5688 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.269 | NA | NA |

| Cheung [47] | 2013 | Hong Kong | 2317 | 16.4 | 0.548 | 12M: 0.0967 | NA | 12M: 0.143 | 12M: 0.14 | NA |

| Choquet [48] | 1990 | France | 1519 | 14.7 | 0.45 | NA | NA | 12M:0.18 | NA | NA |

| Chou [49] | 2013 | Taiwan | 2835 | 19.75 | 0.554 | 12M: 0.105 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Claes [50] | 2013 | Belgium | 532 | 15.11 | 0.258 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.265 | NA |

| Coughlan [51] | 2014 | Ireland | 212 | 11.54 | 0.519 | LT: 0.005 | NA | LT: 0.068 | LT: 0.066 | 0.068 |

| Donald [52] | 2001 | Australia | 3082 | NA | NA | LT: 0.0185 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Doyle [53] | 2015 | Ireland | 856 | NA | 0.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.12 |

| Fleming [54] | 2007 | New Zealand | 9570 | NA | 0.539 | 12M:0.078 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Garisch [55] | 2015 | New Zealand | 1162 | 16.35 | 0.615 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.696 | NA |

| Ghrayeb [56] | 2014 | Palestine | 720 | 15.4 | 0.496 | NA | 12M: 0.253 | 12M: 0.246 | NA | NA |

| Giletta [57] | 2012 | Italy, Netherlands, United States | 1862 | 15.69 | 0.49 | NA | NA | NA | 12M: 0.24 | NA |

| Gonzalez-Forteza [55] | 2005 | Mexico | 2531 | 16.67 | 0.544 | 0.808 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.072 |

| Grunbaum [58] | 2001 | United States | 16262 | 16.16 | NA | 12M: 0.077 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Han [59] | 2016 | United States | 135300 | NA | 0.498 | 12M: 0.013 | 12M:0.0214 | 12M: 0.069 | NA | NA |

| Han [60] | 2018 | United States | 17000 | NA | NA | 12M:0.016 | 12M:0.027 | 12M: 0.083 | NA | NA |

| Hawton [61] | 2002 | United Kingdom | 5801 | NA | 0.466 | NA | NA | 12M: 0.149 | NA | 12M: 0.069 |

| Hesketh [62] | 2002 | China | 1576 | NA | NA | LT: 0.090 | NA | LT: 0.160 | NA | NA |

| Kądziela-Olech [63] | 2015 | Poland | 2220 | 16.7 | 0.463 | NA | NA | NA | 12M:0.048 | 12M:0.083 |

| Kang [64] | 2015 | South Korea | 72623 | NA | NA | 12M: 0.049 | 12M: 0.191 | 12M:0.191 | NA | NA |

| Kataoka [65] | 2014 | Japan | 9778 | NA | 0.486 | NA | NA | 12M: 0.05 | NA | NA |

| Kidger [66] | 2012 | England | 4855 | 16.67 | 0.589 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.186 |

| Kvernmo [67] | 2009 | Norway | 447 | 14.7 | 0.526 | NA | NA | 12M:0.161 | NA | LT: 0.136 |

| Kirmayer [68] | 1996 | Canada | 99 | 19.4 | 0.516 | LT: 0.341 | NA | LT: 0.429 | NA | NA |

| Larsson [69] | 2008 | Norway | 2464 | 13.7 | 0.508 | LT: 0.030 | NA | LT: 0.040 | LT: 0.029 | NA |

| Laskyte [70] | 2009 | Lithuania | 3848 | NA | 0.572 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT:0.07 |

| Law [13] | 2013 | Hong Kong | 2579 | 12 | 0.5 | 12M: 0.039 | NA | 12M:0.046 | NA | 12M:0.233 |

| Laukkanen [71] | 2009 | Finland | 4205 | 15.58 | 0.536 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.217 |

| Le [72] | 2011 | Vietnam | 7584 | NA | 0.560 | LT: 0.005 | NA | LT: 0.034 | NA | LT: 0.028 |

| Lee [73] | 2008 | South Korea | 368 | NA | 0.389 | LT: 0.033 | NA | TW: 0.098 | NA | NA |

| Lee [74] | 2013 | South Korea | 74698 | NA | 0.472 | 12M:0.0597 | NA | 12M:0.238 | NA | NA |

| Lewinsohn [75] | 1996 | USA | 1709 | NA | NA | LT: 0.071 | LT: 0.083 | LT: 0.129 | NA | NA |

| Lin [76] | 2017 | Taiwan | 2170 | 15.83 | 0.511 | NA | NA | NA | 12M:0.2 | NA |

| Liu [77] | 2018 | China | 11831 | 14.97 | 0.49 | LT: 0.040 | LT: 0.098 | LT: 0.205 | NA | NA |

| Lucassen [78] | 2011 | New Zealand | 9107 | NA | 0.46 | 12M: 0.042 | NA | 12M:0.125 | NA | 12M:0.184 |

| Madu [79] | 2003 | South America | 435 | 17.25 | 0.559 | LT: 0.209 | LT: 0.161 | LT: 0.371 | NA | NA |

| Mahfoud [80] | 2011 | Lebanon | 5109 | 13.8 | 0.543 | NA | NA | 12M: 0.157 | NA | NA |

| Madge [5] | 2008 | Australia/Belgium/ England/Hungary/ Ireland/The Netherlands/ Norway. | 30427 | 15.6 | 0.49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.089 |

| Matsumoto [81] | 2008 | Japan | 1726 | 14.5 | 0.51 | NA | NA | LT: 0.398 | NA | LT: 0.099 |

| McCann [82] | 2010 | Ireland | 3178 | NA | 0.59 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.105 |

| Meehan [83] | 1992 | United States | 694 | NA | NA | LT: 0.104 | NA | LT 0.539 | NA | NA |

| Mohl [84] | 2011 | Denmark | 2864 | 17 | 0.608 | NA | NA | LT: 0.215 | NA | NA |

| Mojs [85] | 2012 | Poland | 1065 | NA | 0.72 | NA | NA | LT: 0.015 | NA | NA |

| Morey [86] | 2008 | Ireland | 3646 | 16.01 | 0.53 | NA | NA | LT: 0.056 | NA | LT: 0.091 |

| Morey [87] | 2017 | England | 2000 | 15.6 | 0.52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.155 |

| Muehlenkamp [88] | 2009 | United States | 1375 | 15.48 | 0.561 | LT: 0.065 | NA | NA | LT: 0.214 | NA |

| Muehlenkamp [89] | 2011 | United States | 390 | 16.27 | 0.549 | LT: 0.056 | NA | NA | LT 0.159 | NA |

| Nada-Raja [90] | 2004 | New Zealand | 966 | NA | 0.489 | LT: 0.092 | NA | LT: 0.090 | NA | LT: 0.135 |

| Nath [91] | 2012 | India | 1817 | 19.11 | NA | LT: 0.040 | NA | LT: 0.116 | NA | NA |

| Nixon [92] | 2008 | Canada | 568 | 15.2 | 0.537 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.169 | NA |

| Nobakht [93] | 2017 | Iran | 200 | NA | 0.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.405 |

| Nock [94] | 2013 | USA | 6483 | NA | 0.482 | LT: 0.040 | LT: 0.040 | LT: 0.121 | NA | NA |

| O’Connor [95] | 2009 | Scotland | 1967 | NA | 0.534 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.138 |

| Omigbodun [96] | 2008 | Nigeria | 1429 | 14.4 | 0.491 | 12M: 0.117 | NA | 12M: 0.229 | NA | NA |

| Patton [97] | 1997 | Australia | 1699 | NA | NA | 12M: 0.002 | NA | NA | NA | 12M: 0.051 |

| Pawlowska [98] | 2016 | Poland | 5685 | 17.18 | 0.3 | LT: 0.044 | LT: 0.150 | LT: 0.243 | NA | LT: 0.137 |

| Pérez-Amezcua [99] | 2010 | Mexico | 12424 | NA | 0.55 | LT: 0.088 | NA | LT: 0.466 | NA | NA |

| Plener [100] | 2009 | USA | 665 | 14.8 | 0.571 | LT: 0.065 | NA | LT: 0.359 | LT: 0.256 | NA |

| Portzky [101] | 2008 | Netherlands/Belgium | 8889 | 15.48 | 0.51 | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.072 |

| Rey Gex [102] | 1998 | Switzerland | 9268 | 17.46 | 0.431 | LT: 0.030 | NA | 12M: 0.172 | NA | NA |

| Rudatsikira [103] | 2007 | Guyana | 1197 | NA | 0.579 | NA | NA | 12M: 0.184 | NA | NA |

| Rudd [104] | 1989 | United States | 737 | NA | 0.61 | 12M: 0.056 | NA | 12M:0.437 | NA | NA |

| Sampasa-Kanyinga [105] | 2017 | Canada | 1922 | 14.4 | 0.54 | 12M: 0.029 | NA | 12M: 0.105 | NA | NA |

| Sarno [106] | 2010 | Italy | 578 | NA | 0.825 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.206 | NA |

| Shaikh [107] | 2014 | India | 5184 | NA | 0.248 | NA | 12M:0.076 | 12M: 0.033 | NA | NA |

| Shek [108] | 2012 | Hong Kong | 3328 | 12.59 | 0.472 | NA | 12M:0.0475 | 12M: 0.134 | NA | 12M: 0.327 |

| Sidhartha [109] | 2006 | India | 1205 | 14.73 | 0.4 | LT: 0.080 | NA | LT: 0.217 | NA | LT: 0.180 |

| Silviken [110] | 2007 | Norway | 2691 | 16.9 | 0.521 | LT: 0.095 | NA | SM: 0.151 | NA | NA |

| Soares [111] | 2015 | Brazil | 549 | NA | 0.801 | LT:0.027 | NA | LT: 0.118 | NA | NA |

| Somer [112] | 2015 | Turkey | 1656 | 16.8 | 0.55 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.313 | NA |

| Sornberger [113] | 2012 | Canada | 1744 | 14.92 | 0.508 | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.245 | NA |

| Straub [114] | 2015 | Germany | 1117 | 14.83 | 0.527 | LT:0.056 | NA | LT: 0.317 | NA | NA |

| Tang [115] | 2011 | Hong Kong | 2013 | 15.6 | 0.453 | 12M: 0.0348 | NA | 12M:0.088 | 12M: 0.155 | NA |

| Tang [116] | 2018 | China | 15623 | 15.2 | 0.485 | 12M: 0.0443 | 12M:0.08 | 12M: 0.159 | 12M: 0.292 | NA |

| Teo [117] | 2011 | Australia | 207 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | LT: 0.14 |

| Thaku [118] | 2015 | India | 705 | NA | 0.488 | NA | NA | 12M: 0.309 | NA | NA |

| Toprak [119] | 2010 | Turkey | 636 | 19.36 | 0.539 | LT:0.072 | NA | LT: 0.126 | NA | LT: 0.171 |

| Tresno [120] | 2012 | Indonesia | 207 | 19.78 | NA | LT:0.121 | NA | NA | LT: 0.565 | NA |

| Valdez-Santiago [121] | 2017 | Mexico | 21509 | 15.4 | NA | LT: 0.027 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Vawda [122] | 2013 | South Africa | 222 | 13.3 | 0.482 | LT: 0.054 | LT: 0.059 | LT 0.225 | NA | NA |

| Ventura-Junca [123] | 2010 | Chile | 1567 | 16.2 | 0.459 | LT: 0.190 | NA | LT: 0.620 | NA | NA |

| Wan [124] | 2011 | China | 17622 | 16.1 | 0.512 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 12M: 0.17 |

| Whitlock [125] | 2011 | United States | 11529 | NA | 0.576 | NA | NA | NA | LT:0.154 | NA |

| Xin [126] | 2017 | China | 11880 | 14.62 | 0.505 | 12M: 0.0491 | 12M:0.11 | 12M: 0.209 | NA | 12M: 0.30 |

| Zetterqvist [127] | 2013 | Sweden | 3060 | NA | 0.505 | NA | NA | NA | 12M:0.356 | NA |

| Zubrick [128] | 2016 | Australia | 2563 | NA | 0.692 | 12M: 0.0241 | 12M: 0.052 | 12M: 0.075 | 12M:0.08 | NA |

3.2. Aggregate Prevalence of Suicide Attempts in Children and Adolescents

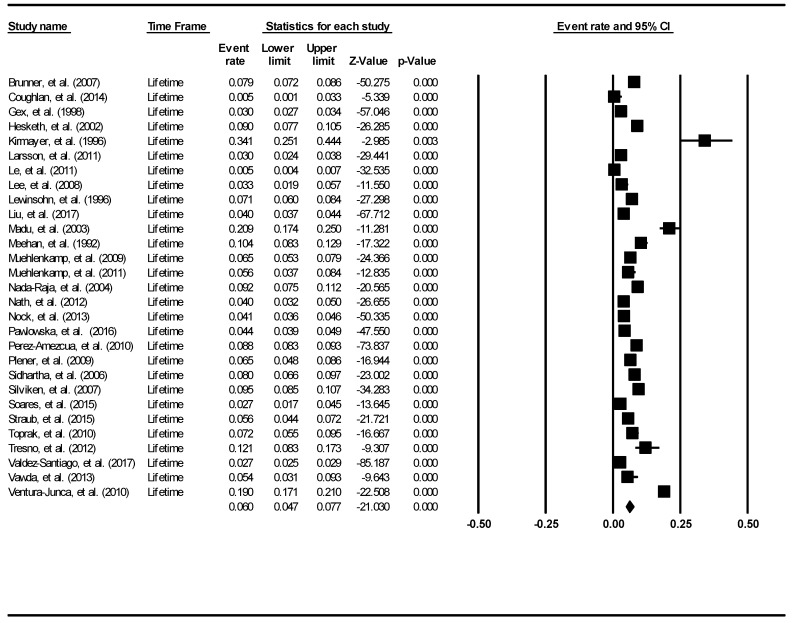

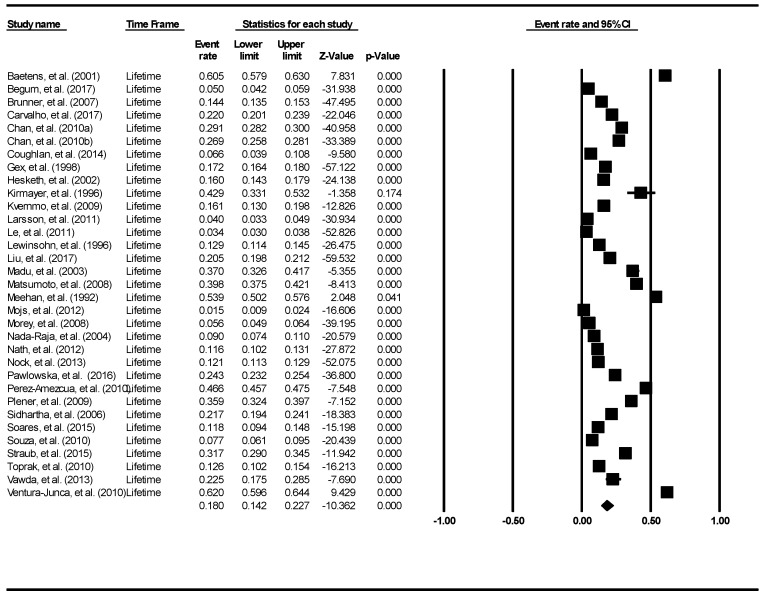

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was found to be 6.0% (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 4.7–7.7%). The forest plot is shown in Figure 2. There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 98.60, p <0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias (intercept = 0.16, 95% CI: −5.87–6.2, t = 0.06, df = 27, p = 0.96).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts.

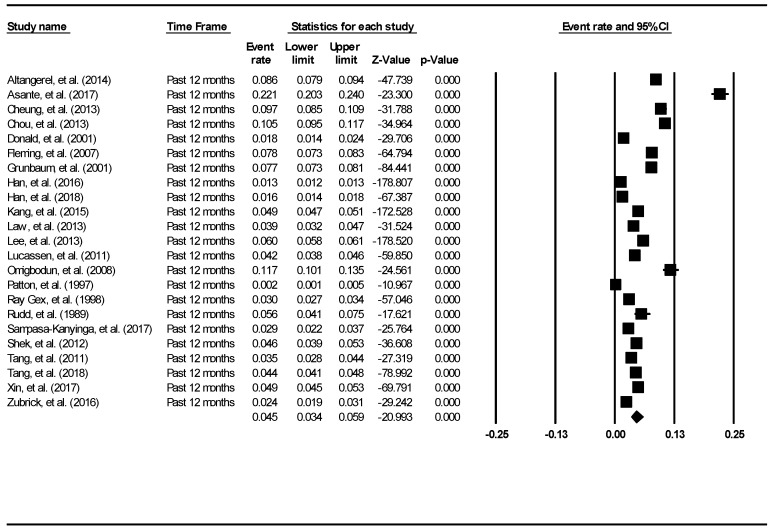

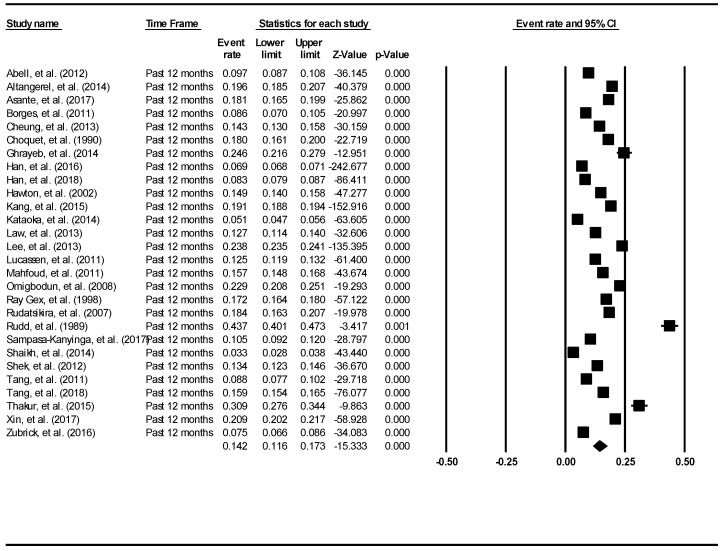

The aggregate 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts was found to be 4.5% (95% CI: 3.4–5.9%). The result is demonstrated using the forest plot as shown in Figure 3. There was a significant high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.64, p < 0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias (intercept = 0.39, 95% CI: −11.71–12.49, t = 0.07, df = 21, p = 0.95).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the aggregate 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts.

3.3. Aggregate Prevalence of Suicide Plans in Children and Adolescents

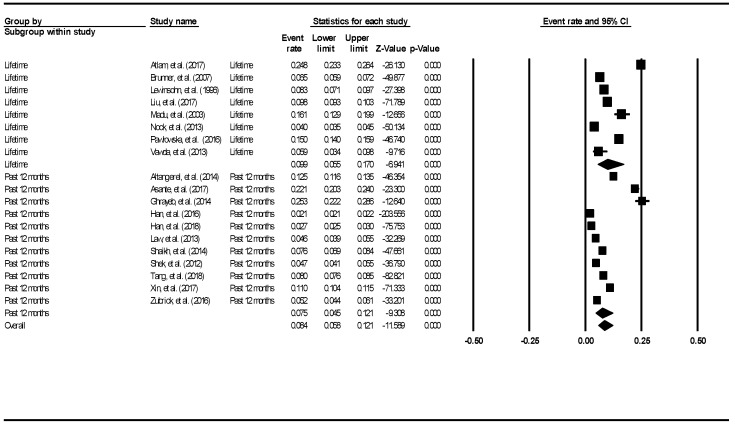

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide plans was found to be 9.9% (95% CI: 5.5–17.0%). The result is demonstrated using the forest plot, as shown in Figure 4. There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.35, p < 0.001). The aggregate 12-month prevalence of suicide plans was found to be 7.5% (95% CI: 4.5–12.1%). There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.82, p < 0.001). The result is demonstrated using the forest plot, as shown in Figure 4. There was no evidence of publication bias (intercept = 15.24, 95% CI: −5.06–35.54, t = 1.58, df = 17, p = 0.13).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal plans.

3.4. Aggregate Prevalence of Suicide Ideation in Children and Adolescents

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation was found to be 18% (95% CI: 14.2–22.7%). The result is demonstrated using the forest plot, as shown in Figure 5. There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.68, p <0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias (intercept = −11.18, 95% CI: −21.49–0.88, t = 2.21, df = 31, p = 0.03).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the lifetime aggregate prevalence of suicidal ideation.

The aggregate 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation was found to be 14.2% (95% CI: 11.6–17.3%). The result is demonstrated using the forest plot as shown in Figure 6. There was a significant high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.82, p < 0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias (intercept = −5.18, 95% CI: −18.64–8.29, t = 0.79, df = 26, p = 0.44).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the aggregate 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation.

3.5. Aggregate prevalence of Non-Suicidal Self Injury in Children and Adolescents

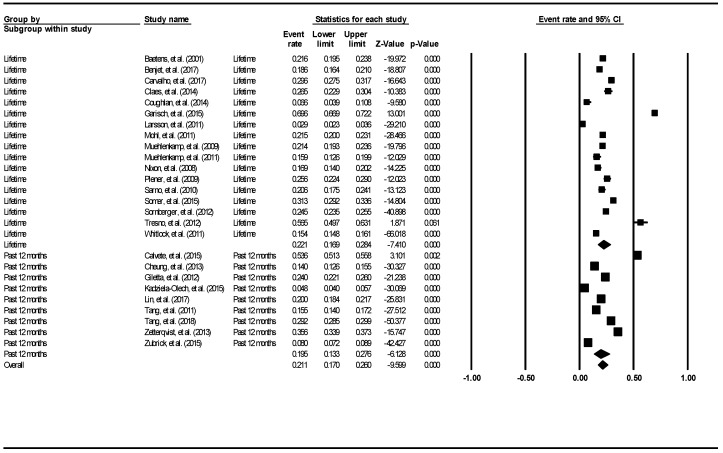

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury was 22.1% (95% CI: 16.9–28.4%). The result is demonstrated using the forest plot, as shown in Figure 7. There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.22, p < 0.001). The aggregate 12-month prevalence was 19.5% (95% CI: 13.3–27.6%). There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.63, p < 0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias (intercept = −4.84, 95% CI: −14.85–6.174, t = 1.0, df = 24, p = 0.33).

Figure 7.

Forest plot of the aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury.

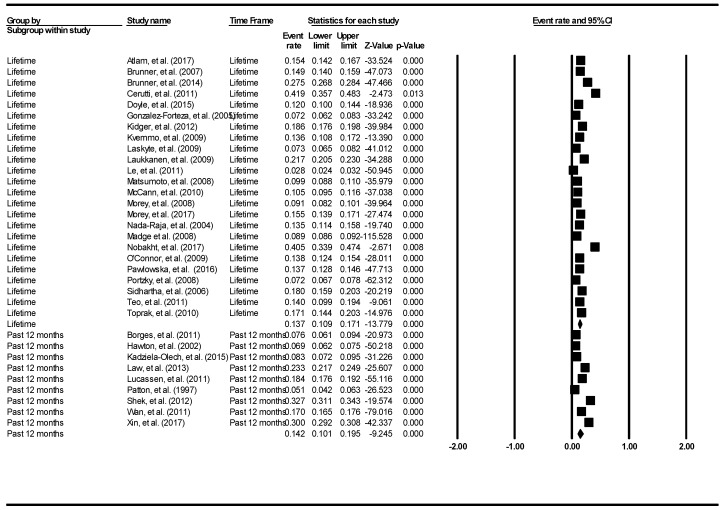

3.6. Aggregate Prevalence of Deliberate Self-Harm in Children and Adolescents

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of deliberate self-harm was 13.7% (95% CI: 10.9–17.1%). The result is demonstrated using the forest plot, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of the aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm.

There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.46, p < 0.001). The aggregate 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm was 14.2% (95% CI: 10.1–19.5%). There was a significantly high level of heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 99.63, p < 0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias (intercept = −9.21, 95% CI: −18.93–0.52, t = 1.93, df = 31, p = 0.06).

3.7. Subgroup Analyses Based on School Attendance

A higher aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts is found amongst young people who attended school full-time as compared to young people from the mixed group of education consisting partial and non-school attendees (6.7% (95% CI: 5.3–8.4%) vs. 4.3% (95% CI: 2.7–6.7%)). The aggregate prevalence of suicide attempts in the past 12 months for full-time school attendees (5.6%, 95% CI: 4.2–7.3%) was found to be higher than partial and non-school attendees (2.1%, 95% CI: 1.3–3.6%).

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide plans was found to be 12.4% (95% CI: 8.5–17.8%) in young people who attended school as compared to 5.1% (95% CI: 2.6–9.9%) from partial and non-school attendees. Similarly, the aggregate 12-month prevalence of suicide plans was also higher in the school-attending group (10.3%, 95% CI: 7.6–13.7%) as compared to partial and non-school attending group (3.1%, 95% CI: 1.8–5.2%).

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation were found to be higher in the school-attending group as compared to the partial and non-school attending group (19.5%, 95% CI: 15.0–25.0% vs. 13.9%, 95% CI: 8.5–22.1%) and (14.6%, 95% CI: 11.8–18.0% vs. 12.4%, 95% CI: 7.7–19.5%) respectively.

Both the lifetime and 12-month aggregate prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury were higher in the school-attending group as compared to the partial and non-school attending group (22.8%, 95% CI: 17.1–29.8% vs. 19.0%, 95% CI: 9.7–33.7%), and (21.5%, 95% CI: 15.0–30.0% vs. 8.0%, 95% CI: 2.4–23.3%) respectively.

There was a higher aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm in the school-attending group (15.3%, 95% CI: 11.7–19.9%) compared to the partial and non-school attending group (10.4%, 95% CI: 6.6–15.9%).

3.8. Subgroup Analyses Based on Western and Non-Western Countries

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was higher in Western (6.5%, 95% CI: 4.7–9.0%) than non-Western countries (5.4%, 95% CI: 3.6–7.9%). In contrast, aggregate prevalence of suicide attempts in the past 12 months was higher in non-Western countries (6.9%, 95% CI: 4.8–9.6%) than western (2.8%, 95% CI: 1.9–4.0%).

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide plans was higher in non-Western (12.9%, 95% CI: 6.7–23.3%) than Western countries (7.6%, 95% CI: 3.9–14.3%). Similarly, the aggregate past 12-month prevalence of suicide plans was higher in non-Western (10.3%, 95% CI: 7.6–13.7%) than Western countries (3.1%, 95% CI: 1.8–5.2%).

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation was higher in non-Western (18.7%, 95% CI: 12.5–26.9%) than Western countries (17.6%, 95% CI: 12.7–23.8%). The aggregate 12-month prevalence of SI was higher in non-Western (15.2%, 95% CI: 12.6–18.1%) than Western countries (13.0%, 95% CI: 10.5–16.1%).

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury was higher in non-Western countries (32.6%, 95% CI: 20.0–48.5%) than Western countries (19.4%, 95% CI: 14.2–25.8%). The aggregate 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury was similar between in non-Western (19.1%, 95% CI: 9.3–35.3%) and the Western countries (19.7%, 95% CI: 10.4–34.2%).

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of deliberate self-harm was higher in Western countries (14.2%, 95% CI: 10.7–18.6%) than non-Western countries (12.8%, 95% CI: 8.5–18.7%). The aggregate 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm was higher in non-Western countries (25.2%, 95% CI: 16.8–36.0%). than Western countries (8.5%, 95% CI: 5.5–12.8%).

3.9. Subgroup Analyses Based on Developing and Developed Countries

The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in developed (6.1% 95% CI: 4.3–8.5%) and low and middle-income countries (6.0% 95% CI: 4.1–7.7%) were similar. However, the past 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts was higher in low and middle-income countries (6.9% 95% CI: 4.8–9.6%) than developed countries (2.8% 95% CI: 1.9–4.0%).

The lifetime prevalence of suicide plans was higher in developing (12.9% 95% CI: 6.7–23.3%) than developed countries (7.6% 95% CI: 3.9–14.3%). Similarly, the 12-month prevalence of suicide plans was higher in low and middle-income countries (10.3% 95% CI: 7.6–13.7%) than developed countries (3.1% 95% CI: 1.8–5.2%).

The lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation was higher in developing (17.7% 95% CI: 11.1–27.0%) than developed countries (17.3% 95% CI: 12.0–24.4%). The 12-month prevalence of suicide ideation was higher in low and middle-income countries (15.9% 95% CI: 13.5–18.6%) than developed countries (11.9% 95% CI: 9.6–14.7%).

The lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury was significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries (33.7% 95% CI: 19.0–52.5%) as compared to developed countries (20.0% 95% CI: 14.9–26.4%). However, the 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury was found to be similar between developed countries (19.7% 95% CI: 10.4–34.2%) and low- and middle-income countries (19.1% 95% CI: 9.3–35.3%).

The lifetime prevalence of deliberate self-harm was similar between low- and middle-income countries (13.9% 95% CI: 10.6–18.1%) and developed countries (13.2% 95% CI: 8.5–19.9%). The past 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm was found to be higher in low- and middle-income countries (25.2% 95% CI: 16.8–36.0%) than developed countries (8.5 % 95% CI: 5.5–12.8%).

3.10. Subgroup Analyses Based on Continents

The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was found to be highest in South America (19.0% 95% CI: 17.1–21.0%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in Africa was 11.2% (95% CI: 2.7%–36.1%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in Australia was 9.2% (95% CI: 7.5%–11.2%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in North America was 8.6% (95% CI: 5.4–13.6%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was lowest in Asia 4.6% (95% CI: 2.7–7.6%) and Europe 4.6% (95% CI: 3.2–6.6%).

The past 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts was found to be highest in Africa at (16.3% 95% CI: 8.4–29%). The past 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts in Asia was 5.8% (95% CI: 4.9–6.7%). The past 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts in Europe was 3% (95% CI: 2.7–3.4%). The past 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts in North America was 3% (95% CI: 1.1–8%). The past 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts was lowest in Australia (2.4%, 95% CI: 1.4–4.4%).

For the lifetime and 12-month prevalence for suicide plans, Asia had the highest prevalence (10.4% 95% CI: 7.7–13.9%). The lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide plans in Africa was 13.9% (95% CI: 8.1–22.8%). The lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide plans in Europe was 10% (95% CI: 4.3%–21.6%). The lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide plans in Australia was 5.2% (95% CI: 4.4–6.1%). The lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide plans were lowest in North America (3.7%, 95% CI: 2.3–5.9%).

The lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation was found to be highest in Africa (37.0%, 95% CI: 32.6–41.7%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation in North America was 30.2% (95% CI: 13.4–54.8%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation in South America was 28.5% (95% CI: 8.8–62.3%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation in Asia was 14.2% (95% CI: 8.5–22.7%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation was lowest in Europe (13.7% 95% CI: 9–20.2%).

The past 12-month prevalence of suicide ideation was found to be highest in Africa months (20.6%, 95% CI: 13.7–29.7%). The past 12-month prevalence of suicide ideation in South America was 18.4% (95% CI: 16.3–20.7%). The past 12-month prevalence of suicide ideation in Europe was 16.3% (95% CI: 15.3–17.5%). The past 12-month prevalence of suicide ideation in North America was 12.8% (95% CI: 6.4–24.1%). The lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation was lowest in Asia (13.3%, 95% CI: 10.9–16.3%).

The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury were found to be highest in Australia (30.9%, 95% CI: 1.8–91.7%). The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in Asia was 25.7% (95% CI: 18.9–33.8%). The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in North America was 18.7% (95% CI: 14.3–24%). The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury were lowest in Europe (18.4%, 95% CI: 12.1–27.2%).

The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm was found to be highest in Asia (17.4%, 95% CI: 12.5–23.7%). The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm in Europe was 12.9% (95% CI: 10.3–16.0%). The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm in Australia was 11.1% (95% CI: 5.4–21.3%). The lifetime and past 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm was lowest in North America (7.3%, 95% CI: 6.5–8.2%).

3.11. Meta-Regression Analyses

For suicide attempts, mean age (B = 0.0812, z = 2.12, p = 0.034) was identified as significant moderator that contributed to heterogeneity between studies. For suicidal plan, mean age (B = 0.20, z = 5.63, p < 0.001) was identified as significant moderator that contributed to heterogeneity between studies. For SI, mean age (B = −0.0087, z = −0.28, p = 0.78) was a non-significant moderator. For non-suicidal self-injury, mean age (B = 0.11, z = 1.77, p = 0.08). was a non-significant moderator. Fordeliberate self-harm, mean age (B = 0.01, z = 0.33, p = 0.74) was a non-significant moderator.

For suicide attempts, the proportion of females (B = 1.86, z = 1.05, p = 0.29) was a non-significant moderator. For suicidal plan, the proportion of females (B = −0.36, z = −0.14, p = 0.89) was a non-significant moderator. For suicidal ideation, the proportion of females (B = 0.77, z = 0.63 p = 0.53) was a non-significant moderator. For non-suicidal self-injury, the proportion of females (B = −0.29, z = −0.25, p = 0.81) was a non-significant moderator. For deliberate self-harm, the proportion of females (B = −1.79, z = −0.85, p = 0.4) was a non-significant moderator.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that analyzed suicidal and self-harm phenomena based on 686,672 young people worldwide. The key findings are summarized as follows. non-suicidal self-injury was most frequent with aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of 22.1% and 19.5% respectively. Suicidal ideation was second most frequent with aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of 18% and 14.2% respectively. Deliberate self-harm was third most frequent with aggregate lifetime and 12-montnh prevalence of 13.7% and 14.2% respectively. Suicidal plan ranked fourth with aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence 9.9% and 7.5% respectively. Suicide attempt was least frequent with aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of 6.0% and 4.5% respectively.

This meta-analysis found that the aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was higher in Western (6.5%, 95% CI: 4.7–9.0%) than non-Western countries. There are several reasons to explain higher prevalence of suicide attempts among young people in western countries. First, substance abuse appeared to have affected suicide rates of young males in Western countries [129]. Second, high suicide rates among young indigenous people in Western countries have been attributed to internalised anger and despair related to social disruption and disempowerment [130]. Third, young people in Western countries could have more access to suicide means, including firearms. In contrast, the aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide plans, suicide ideation and non-suicidal self-injury were higher in non-Western countries than Western countries. This finding suggests that young people in non-Western countries could have thought about suicide but did not attempt suicide. Attempted suicide is illegal in some of the non-Western countries including Bangladesh, Hungary, India and Japan, though in Japan it is not punishable [129]. The legal implication could deter suicide attempts in some of the non-Western countries.

This meta-analysis found that non-suicidal self-injury had the highest aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence worldwide. Non-suicidal self-injury is defined as the intentional destruction of one’s own body tissue without suicidal intent [27]. Examples of non-suicidal self-injury, including self-laceration, skin scratching, burning and hitting. Klonsky et al. proposed functional theories that explain the reasons for non-suicidal self-injury in young people [131]. The reasons include alleviation of negative emotion, self-punishment, self-directed anger, and expression of distress. Klonsky et al. highlighted the misconception that non-suicidal self-injury is always a symptom of borderline personality disorder [132]. For young people with engaging non-suicidal self-injury, a psychological intervention which aims at building positive emotion, reducing self-directed anger and promoting more adaptive way to express distress may reduce the prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury.

A recent study found that the 12-month prevalence rates of youth self-harm in low and middle- income countries were comparable to high-income countries. This meta-analysis with a larger sample size showed that children and adolescents from low- and middle-income countries with lower income had a higher aggregate 12-month prevalence of deliberate self-harm than children and adolescents from developed countries with higher income. Previous research reported that non-suicidal self-injury appeared to be more common among Caucasians than non-Caucasians [133]. Our meta-analysis found that the 12-month prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury was highest in Australia which has 74.3% of the population who are Caucasians [134].

The subgroup analysis yielded several interesting findings. The aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal and self-harm behavior were higher in full-time school attendees as compared with partial and non-attendees. School attendees are more likely to be exposed to risk factors, including academic stress and school bullying. Academic stress leads to anger, anxiety, helplessness, shame, and boredom [135]. A previous study found that skin picking, which causes skin damage was positively correlated with academic stress and trait anxiety was a predisposing factor [136]. The other risk factors faced by school attendees are peer victimization, which reflects the experience of overt (e.g., hitting, pushing), reputational (e.g., spreading rumors), or relational aggression from peers (e.g., being excluded, gossiped about) [137,138]. Vergara et al. (2019) found that peer victimization was associated with the frequency of past month non-suicidal self-injury thoughts and past month non-suicidal self-injury behaviors [139]. The aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal and self-harm behavior were higher in developing and non-western countries.

We found that the lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation, the 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts and suicide ideation were highest in Africa. This could be due to the fact that large numbers of African children and adolescents were exposed to adverse childhood experiences [140]. Young people in developing and non-western countries are more likely to be exposed to adverse childhood experiences including alcohol abuse [141], lack of access to care for mental health problems, orphanage, and early parental death [142], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [142] and violence against children and adolescents [143]. Interventions to reduce African children and adolescent suicidality include those improving family functioning, reducing poverty, mitigating the impacts of HIV and the provision of effective mental health services for adversity-exposed children and adolescent [140]. As the infrastructure for mental health service is still developing, the main challenge is to reach out to children and adolescents in low and middle-income countries and educate them to handle suicidal and self-harm behaviors. Electronic health (E-health) was found to provide a cost-effective solution in mental health [144]. As the use of smartphones becomes increasingly prevalent and affordable, more children and adolescents in low and middle-income countries can own a smartphone device and download health-related applications [17]. Proof of concept feasibility studies and randomized trials should be conducted in low and middle-income countries to determine that smartphone applications are efficacious to reduce suicidal and self-harm behavior in children and adolescents before their actual implementation [145].

The lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide plans and DSH were found to be highest in Asia. Asian children and adolescents face more academic-related stress due to the competitiveness in the education system, and getting poor grades in the examination have been found to bear two major significant sources of anxiety and depression amongst Asian children and adolescents [146]. Willingness to seek help was found to be a protective factor against suicidal and self-harm behavior for Asian children and adolescents [15]. Nevertheless, help-seeking from peers may not be beneficial [147]. Children and adolescents may not receive the help that they require, as peers often might be poorly equipped to provide appropriate advice.

Meta-regression found that age was a critical moderator that explains for heterogeneity for a lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts and suicide plans. Children and young adolescents were less exposed to suicide risk factors as compared with older adolescents [148]. Older adolescents are predisposed to specific risk factors associated with suicidal behaviors, including baseline interpersonal problems in one’s social circle [149], psychiatric disorders [148], and STD-related risk [150]. Meta-regression also found that gender was not a vital moderator that explains for heterogeneity of the prevalence of suicidal and self-harm behavior. This finding may challenge the gender paradox, which suggests significant epidemiological differences in suicidal and self-harm behaviors between adolescent females and males [151]. A previous study found that there were no gender differences in family problems and school problems which are well-known risk factors associated with suicidal and self-harm behavior in young people [152].

The strengths of this meta-analysis include an extensive search in identifying a large number of articles on suicidal and self-harm behaviour in 686,672 children and adolescents, adherence to the guidelines, the inclusion of meta-regression and subgroup analysis as well as lack of publication bias [28]. Nevertheless, this meta-analysis has several limitations. First, this meta-analysis classified suicidal and self-harm phenomena into five sub-categories and not able to study their inter-relationship. Klonsky et al. proposed that non-suicidal self-injury may be an essential risk factor for suicidal behaviour [132]. Future study is required to study the inter-relationship between suicidal behaviour, deliberate self-harm, and non-suicidal self-injury in young people. Second, we could not classify dliberate self-harm as suicidal and non-suicidal deliberate self-harm. Future research is required to understand the differences between young people who attempt suicidal and non-suicidal deliberate self-harm.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis found that the three most common suicidal and self-harm behaviors were non-suicidal self-injury (aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of 22.1% and 19.5% respectively), suicidal ideation (aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of 18% and 14.2% respectively) and deliberate self-harm (aggregate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of 13.7% and 14.2% respectively). The aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was higher in Western than non-Western countries, in contrast, the aggregate lifetime prevalence of suicide plans, suicide ideation and non-suicidal self-injury were higher in non-Western countries than Western countries. Suicidal and self-harm behavior was higher in children and adolescents who were full-time school attendees and those who live in developing countries. Meta-regression analyses showed that the mean age of participants was a significant moderator that contributed to heterogeneity for a lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts and suicidal plans. Psychological interventions targeting self-harm and suicidal behavior, social interventions targeting adversities in low- and middle-income countries, and electronic—health interventions to reach out to children and adolescents may reduce the global prevalence of suicidal and self-harm behavior in children and adolescents.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all authors of the full-text articles.

Author Contributions

K.-S.L., C.H.W., C.S.H., and R.C.H. contributed to the concept and design of this study. K.-S.L., R.C.H., and C.S.H. contributed to the data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. K.-S.L., C.H.W., J.W., W.T., Z.Z. and R.C.H. drafted the manuscript. B.X.T. and R.S.M. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of publication.

Funding

J.W. and Z.Z. declared the receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. This study was supported in part by National Science Education Planning Project, China (BIA180193).

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Suicide Rates 2017. [(accessed on 26 April 2019)]; Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/mental_health/suicide_rates/en/

- 2.Aggarwal S., Patton G., Reavley N., Sreenivasan S.A., Berk M. Youth self-harm in low-and middle-income countries: Systematic review of the risk and protective factors. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2017;63:359–375. doi: 10.1177/0020764017700175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho C.S., Ong Y.L., Tan G.H., Yeo S.N., Ho R.C. Profile differences between overdose and non-overdose suicide attempts in a multi-ethnic Asian society. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:379. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1105-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitlock J., Muehlenkamp J., Eckenrode J., Purington A., Baral Abrams G., Barreira P., Kress V. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2013;52:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madge N., Hewitt A., Hawton K., de Wilde E.J., Corcoran P., Fekete S., van Heeringen K., De Leo D., Ystgaard M. Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: Comparative findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008;49:667–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choo C., Diederich J., Song I., Ho R. Cluster analysis reveals risk factors for repeated suicide attempts in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2014;8:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson P., Kelvin R., Roberts C., Dubicka B., Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mak K.K., Ho C.S., Chua V., Ho R.C. Ethnic differences in suicide behavior in Singapore. Transcult. Psychiatry. 2015;52:3–17. doi: 10.1177/1363461514543545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choo C.C., Ho R.C., Burton A.A.D. Thematic Analysis of Medical Notes Offers Preliminary Insight into Precipitants for Asian Suicide Attempters: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:809. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skinner R., McFaull S. Suicide among children and adolescents in Canada: Trends and sex differences, 1980-2008. CMAJ. 2012;184:1029–1034. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beautrais A.L., Joyce P.R., Mulder R.T. Youth suicide attempts: A social and demographic profile. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 1998;32:349–357. doi: 10.3109/00048679809065527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choo C.C., Chew P.K.H., Ho R.C. Suicide Precipitants Differ Across the Lifespan but Are Not Significant in Predicting Medically Severe Attempts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:691. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law B.M., Shek D.T. Self-harm and suicide attempts among young Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong: Prevalence, correlates, and changes. J. Pediatric Adolesc. Gynecol. 2013;26:S26–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewinsohn P.M., Rohde P., Seeley J.R., Baldwin C.L. Gender differences in suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40:427–434. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choo C.C., Harris K.M., Ho R.C. Prediction of Lethality in Suicide Attempts: Gender Matters. OMEGA. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0030222817725182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh E., Eggert L.L. Suicide risk and protective factors among youth experiencing school difficulties. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2007;16:349–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Do T.T.T., Le M.D., Van Nguyen T., Tran B.X., Le H.T., Nguyen H.D., Nguyen L.H., Nguyen C.T., Tran T.D., Latkin C.A., et al. Receptiveness and preferences of health-related smartphone applications among Vietnamese youth and young adults. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:764. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5641-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson L., Skegg K., Poore M., Williams S., Taylor B. An adolescent suicide cluster and the possible role of electronic communication technology. Crisis. 2012;33:239–245. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luxton D.D., June J.D., Fairall J.M. Social media and suicide: A public health perspective. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl. 2):S195–S200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puri B., Hall A., Ho R. Revision Notes in Psychiatry. 3rd ed. CRC Press; New York, NY, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman M.M., Berman A.L., Sanddal N.D., O’Carroll P.W., Joiner T.E. Rebuilding the tower of Babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: Suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2007;37:264–277. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Carroll P.W., Berman A.L., Maris R.W., Moscicki E.K., Tanney B.L., Silverman M.M. Beyond the Tower of Babel: A nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1996;26:237–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Soceity for the Study of Self-Injury. [(accessed on 29 April 2019)]; Available online: http://www.itriples.org/isss-aboutself-i.html.

- 24.Cheung M.W., Ho R.C., Lim Y., Mak A. Conducting a meta-analysis: Basics and good practices. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2012;15:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho R.C., Ong H.S., Kudva K.G., Cheung M.W., Mak A. How to critically appraise and apply meta-analyses in clinical practice. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2010;13:294–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim G.Y., Tam W.W., Lu Y., Ho C.S., Zhang M.W., Ho R.C. Prevalence of Depression in the Community from 30 Countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham N., Buvanaswari P., Rathakrishnan R., Tran B.X., Thu G.V., Nguyen L.H., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. A Meta-Analysis of the Rates of Suicide Ideation, Attempts and Deaths in People with Epilepsy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:1451. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16081451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foo S.Q., Tam W.W., Ho C.S., Tran B.X., Nguyen L.H., McIntyre R.S., Ho R.C. Prevalence of Depression among Migrants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:1986. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim R.B.C., Zhang M.W.B., Ho R.C.M. Prevalence of All-Cause Mortality and Suicide among Bariatric Surgery Cohorts: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:1519. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng A., Tam W.W., Zhang M.W., Ho C.S., Husain S.F., McIntyre R.S., Ho R.C. IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha and CRP in Elderly Patients with Depression or Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12050. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30487-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang E.F., Lim S.Z., Tam W.W., Ho C.S., Zhang M.W., McIntyre R.S., Ho R.C. The Effect of Methylphenidate and Atomoxetine on Heart Rate and Systolic Blood Pressure in Young People and Adults with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:1789. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United Nation. [(accessed on 26 April 2019)]; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/overview/

- 33.Abell W.D., Sewell C., Martin J.S., Bailey-Davidson Y., Fox K. Suicide ideation in Jamaican youth: Sociodemographic prevalence, protective and risk factors. West Indian Med. J. 2012;61:521–525. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2011.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altangerel U., Liou J.C., Yeh P.M. Prevalence and predictors of suicidal behavior among Mongolian high school students. Community Ment. Health J. 2014;50:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oppong Asante K., Meyer-Weitz A. Prevalence and predictors of suicidal ideations and attempts among homeless children and adolescents in Ghana. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 2017;29:27–37. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2017.1287708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atlam D.H., Altinoprak A.E., Adam D. Prevalence of risky behaviors and relationship of risky behaviors with substance use among university students. J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2017;30:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baetens I., Claes L., Muehlenkamp J., Grietens H., Onghena P. Non-suicidal and suicidal self-injurious behavior among Flemish adolescents: A web-survey. Arch. Suicide Res. Off. J. Int. Acad. Suicide Res. 2011;15:56–67. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2011.540467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Begum A., Rahman A.K.M.F., Rahman A., Soares J., Reza Khankeh H., Macassa G. Prevalence of suicide ideation among adolescents and young adults in rural Bangladesh. Int. J. Ment. Health. 2017;46:177–187. doi: 10.1080/00207411.2017.1304074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjet C., Gonzalez-Herrera I., Castro-Silva E., Mendez E., Borges G., Casanova L., Medina-Mora M.E. Non-suicidal self-injury in Mexican young adults: Prevalence, associations with suicidal behavior and psychiatric disorders, and DSM-5 proposed diagnostic criteria. J. Affect. Disord. 2017;215:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borges G., Azrael D., Almeida J., Johnson R.M., Molnar B.E., Hemenway D., Miller M. Immigration, suicidal ideation and deliberate self-injury in the Boston youth survey 2006. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2011;41:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunner R., Parzer P., Haffner J., Steen R., Roos J., Klett M., Resch F. Prevalence and psychological correlates of occasional and repetitive deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2007;161:641–649. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunner R., Kaess M., Parzer P., Fischer G., Carli V., Hoven C.W., Wasserman C., Sarchiapone M., Resch F., Apter A., et al. Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior: A comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2014;55:337–348. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calvete E., Orue I., Aizpuru L., Brotherton H. Prevalence and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema. 2015;27:223–228. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2014.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barreto Carvalho C., da Motta C., Sousa M., Cabral J. Biting myself so I don’t bite the dust: Prevalence and predictors of deliberate self-harm and suicide ideation in Azorean youths. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. (Sao Paulo Braz. 1999) 2017;39:252–262. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2016-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerutti R., Manca M., Presaghi F., Gratz K.L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of deliberate self-harm among a community sample of Italian adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2011;34:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan K.L., Straus M.A., Brownridge D.A., Tiwari A., Leung W.C. Prevalence of dating partner violence and suicidal ideation among male and female university students worldwide. J. Midwifery Women’s Health. 2008;53:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheung Y.T., Wong P.W., Lee A.M., Lam T.H., Fan Y.S., Yip P.S. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: Prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of suicide among adolescents in Hong Kong. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013;48:1133–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choquet M., Menke H. Suicidal thoughts during early adolescence: Prevalence, associated troubles and help-seeking behavior. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1990;81:170–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chou C.H., Ko H.C., Wu J.Y., Cheng C.P. The prevalence of and psychosocial risks for suicide attempts in male and female college students in Taiwan. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2013;43:185–197. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claes L., Muehlenkamp J. The Relationship between the UPPS-P Impulsivity Dimensions and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Characteristics in Male and Female High-School Students. Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:654847. doi: 10.1155/2013/654847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coughlan H., Tiedt L., Clarke M., Kelleher I., Tabish J., Molloy C., Harley M., Cannon M. Prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders, deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideation in early adolescence: An Irish population-based study. J. Adolesc. 2014;37:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donald M., Dower J., Lucke J., Raphael B. Prevalence of adverse life events, depression and suicidal thoughts and behaviour among a community sample of young people aged 15-24 years. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2001;25:426–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doyle L., Treacy M.P., Sheridan A. Self-harm in young people: Prevalence, associated factors, and help-seeking in school-going adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015;24:485–494. doi: 10.1111/inm.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fleming T.M., Merry S.N., Robinson E.M., Denny S.J., Watson P.D. Self-reported suicide attempts and associated risk and protective factors among secondary school students in New Zealand. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2007;41:213–221. doi: 10.1080/00048670601050481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garisch J.A., Wilson M.S. Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: Cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2015;9:261–266. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0055-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghrayeb F.A., Mohamed R.A., Ismail I.M., Raifai A.A. Prevalence of Suicide Ideation and Attempt among Palestinian Adolescents: Across-Sectional Study. World J. Med. Sci. 2014;10:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giletta M., Scholte R.H., Engels R.C., Ciairano S., Prinstein M.J. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: A cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grunbaum J.A., Kann L., Kinchen S.A., Williams B., Ross J.G., Lowry R., Kolbe L. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Surveill. Summ. (Wash. DC 2002) 2002;51:1–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb07917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han B., Compton W.M., Eisenberg D., Milazzo-Sayre L., McKeon R., Hughes A. Prevalence and Mental Health Treatment of Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Among College Students Aged 18-25 Years and Their Non-College-Attending Peers in the United States. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2016;77:815–824. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han H., Park B., Park B., Park N., Park J.O., Ahn K.O., Tak Y.J., Lee H.A., Park H. The Pyramid of Injury: Estimation of the Scale of Adolescent Injuries According to Severity. J. Prev. Med. Public Health Yebang Uihakhoe Chi. 2018;51:163–168. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.18.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hawton K., Rodham K., Evans E., Weatherall R. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: Self report survey in schools in England. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2002;325:1207–1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hesketh T., Ding Q.J., Jenkins R. Suicide ideation in Chinese adolescents. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2002;37:230–235. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0536-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kadziela-Olech H., Zak G., Kalinowska B., Wagrocka A., Perestret G., Bielawski M. The prevalence of Non-suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) among high school students in relation to age and sex. Psychiatr. Pol. 2015;49:765–778. doi: 10.12740/psychiatriapolska.pl/online-first/3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang E.H., Hyun M.K., Choi S.M., Kim J.M., Kim G.M., Woo J.M. Twelve-month prevalence and predictors of self-reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among Korean adolescents in a web-based nationwide survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2015;49:47–53. doi: 10.1177/0004867414540752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kataoka C., Nozu Y., Kudo M., Sato Y., Kubo M., Nakayama N., Iwata H., Watanabe M. Relationships between prevalence of youth risk behaviors and sleep duration among Japanese high school students. [Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi] Jpn. J. Public Health. 2014;61:535–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kidger J., Heron J., Lewis G., Evans J., Gunnell D. Adolescent self-harm and suicidal thoughts in the ALSPAC cohort: A self-report survey in England. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kvernmo S., Rosenvinge J.H. Self-mutilation and suicidal behaviour in Sami and Norwegian adolescents: Prevalence and correlates. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2009;68:235–248. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i3.18331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirmayer L.J., Malus M., Boothroyd L.J. Suicide attempts among Inuit youth: A community survey of prevalence and risk factors. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1996;94:8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larsson B., Sund A.M. Prevalence, course, incidence, and 1-year prediction of deliberate self-harm and suicide attempts in early Norwegian school adolescents. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2008;38:152–165. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laskyte A., Zemaitiene N. The types of deliberate self-harm and its prevalence among Lithuanian teenagers. Medicina. 2009;45:132–139. doi: 10.3390/medicina45020017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laukkanen E., Rissanen M.L., Honkalampi K., Kylma J., Tolmunen T., Hintikka J. The prevalence of self-cutting and other self-harm among 13-to 18-year-old Finnish adolescents. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2009;44:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0398-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le L.C., Blum R.W. Intentional injury in young people in Vietnam: Prevalence and social correlates. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13:23–28. doi: 10.37757/MR2011V13.N3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee H.S., Kim S., Choi I., Lee K.U. Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicide ideation and attempts in korean college students. Psychiatry Investig. 2008;5:86–93. doi: 10.4306/pi.2008.5.2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee C.G., Cho Y., Yoo S. The relations of suicidal ideation and attempts with physical activity among Korean adolescents. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2013;10:716–726. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lewinsohn P.M., Rohde P., Seeley J.R. Adolescent Suicidal Ideation and Attempts: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Implications. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1996;3:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00056.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin M.P., You J., Wu Y.W., Jiang Y. Depression Mediates the Relationship between Distress Tolerance and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents: One-Year Follow-Up. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2018;48:589–600. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu Z.Z., Chen H., Bo Q.G., Chen R.H., Li F.W., Lv L., Jia C.X., Liu X. Psychological and behavioral characteristics of suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;226:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lucassen M.F., Merry S.N., Robinson E.M., Denny S., Clark T., Ameratunga S., Crengle S., Rossen F.V. Sexual attraction, depression, self-harm, suicidality and help-seeking behaviour in New Zealand secondary school students. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2011;45:376–383. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.559635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Madu S.N., Matla M.P. Correlations for perceived family environmental factors with substance use among adolescents in South Africa. Psychol. Rep. 2003;92:403–415. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mahfoud Z.R., Afifi R.A., Haddad P.H., Dejong J. Prevalence and determinants of suicide ideation among Lebanese adolescents: Results of the GSHS Lebanon 2005. J. Adolesc. 2011;34:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matsumoto T., Imamura F., Chiba Y., Katsumata Y., Kitani M., Takeshima T. Prevalences of lifetime histories of self-cutting and suicidal ideation in Japanese adolescents: Differences by age. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:362–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCann M., Schubotz D., McCartan C., McCrystall P. 023 Prevalence of self-harm and help-seeking behaviours among young people in Northern Ireland. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2010;64:A9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.120956.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meehan P.J., Lamb J.A., Saltzman L.E., O’Carroll P.W. Attempted suicide among young adults: Progress toward a meaningful estimate of prevalence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1992;149:41–44. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bo M., Peter C., Annika S. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Indirect Self-Harm Among Danish High School Students. Scand. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Psychol. 2014;2:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mojs E., Warchol-Biedermann K., Glowacka M.D., Strzelecki W., Ziemska B., Marcinkowski J.T. Are students prone to depression and suicidal thoughts? Assessment of the risk of depression in university students from rural and urban areas. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. AAEM. 2012;19:770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morey C., Corcoran P., Arensman E., Perry I.J. The prevalence of self-reported deliberate self harm in Irish adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morey Y., Mellon D., Dailami N., Verne J., Tapp A. Adolescent self-harm in the community: An update on prevalence using a self-report survey of adolescents aged 13-18 in England. J. Public Health (Oxf. Engl.) 2017;39:58–64. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muehlenkamp J.J., Williams K.L., Gutierrez P.M., Claes L. Rates of non-suicidal self-injury in high school students across five years. Arch. Suicide Res. Off. J. Int. Acad. Suicide Res. 2009;13:317–329. doi: 10.1080/13811110903266368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Muehlenkamp J.J., Ertelt T.W., Miller A.L., Claes L. Borderline personality symptoms differentiate non-suicidal and suicidal self-injury in ethnically diverse adolescent outpatients. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2011;52:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nada-Raja S., Skegg K., Langley J., Morrison D., Sowerby P. Self-harmful behaviors in a population-based sample of young adults. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2004;34:177–186. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.2.177.32781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nath Y., Paris J., Thombs B., Kirmayer L. Prevalence and social determinants of suicidal behaviours among college youth in India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2012;58:393–399. doi: 10.1177/0020764011401164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nixon M.K., Cloutier P., Jansson S.M. Nonsuicidal self-harm in youth: A population-based survey. CMAJ. 2008;178:306–312. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nobakht H.N., Dale K.Y. The prevalence of deliberate self-harm and its relationships to trauma and dissociation among Iranian young adults. J. Trauma Dissociation Off. J. Int. Soc. Study Dissociation (ISSD) 2017;18:610–623. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2016.1246397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nock M.K., Green J.G., Hwang I., McLaughlin K.A., Sampson N.A., Zaslavsky A.M., Kessler R.C. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.O’Connor R.C., Rasmussen S., Miles J., Hawton K. Self-harm in adolescents: Self-report survey in schools in Scotland. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2009;194:68–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Omigbodun O., Dogra N., Esan O., Adedokun B. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behaviour among adolescents in southwest Nigeria. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2008;54:34–46. doi: 10.1177/0020764007078360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Patton G.C., Harris R., Carlin J.B., Hibbert M.E., Coffey C., Schwartz M., Bowes G. Adolescent suicidal behaviours: A population-based study of risk. Psychol. Med. 1997;27:715–724. doi: 10.1017/S003329179600462X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pawlowska B., Potembska E., Zygo M., Olajossy M., Dziurzynska E. Prevalence of self-injury performed by adolescents aged 16-19 years. Psychiatr. Pol. 2016;50:29–42. doi: 10.12740/PP/36501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Perez-Amezcua B., Rivera-Rivera L., Atienzo E.E., Castro F., Leyva-Lopez A., Chavez-Ayala R. Prevalence and factors associated with suicidal behavior among Mexican students. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52:324–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Plener P.L., Libal G., Keller F., Fegert J.M., Muehlenkamp J.J. An international comparison of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicide attempts: Germany and the USA. Psychol. Med. 2009;39:1549–1558. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Portzky G., De Wilde E.J., van Heeringen K. Deliberate self-harm in young people: Differences in prevalence and risk factors between the Netherlands and Belgium. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2008;17:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0652-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rey Gex C., Narring F., Ferron C., Michaud P.A. Suicide attempts among adolescents in Switzerland: Prevalence, associated factors and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1998;98:28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rudatsikira E., Muula A.S., Siziya S. Prevalence and associated factors of suicidal ideation among school-going adolescents in Guyana: Results from a cross sectional study. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH. 2007;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rudd M.D. The prevalence of suicidal ideation among college students. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1989;19:173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1989.tb01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sampasa-Kanyinga H., Dupuis L.C., Ray R. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health. 2017;29 doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sarno I., Madeddu F., Gratz K.L. Self-injury, psychiatric symptoms, and defense mechanisms: Findings in an Italian nonclinical sample. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2010;25:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shaikh M.A. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal expression among school attending adolescents in Pakistan. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2014;64:99–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shek D.T., Yu L. Self-harm and suicidal behaviors in Hong Kong adolescents: Prevalence and psychosocial correlates. Sci. World J. 2012;2012:932540. doi: 10.1100/2012/932540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sidhartha T., Jena S. Suicidal behaviors in adolescents. Indian J. Pediatrics. 2006;73:783–788. doi: 10.1007/BF02790385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Silviken A., Kvernmo S. Suicide attempts among indigenous Sami adolescents and majority peers in Arctic Norway: Prevalence and associated risk factors. J. Adolesc. 2007;30:613–626. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Soares M.J., Amaral A., Pereira A.T., Madeira N., Bos S., Valente J., Nogueira V., Oliveira L.A., Roque C., Macedo A. Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation Among Students. Eur. Psychiatry. 2015;30:1802. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(15)31387-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]