Abstract

We report a teenager with childhood onset focal seizures associated with the chapeau de gendarme sign or ictal pouting of anterior insular lobe origin. The chapeau de gendarme sign has been associated with frontal lobe seizures in patients with focal epilepsy. However, in this case, stereo-electroencephalography (SEEG) localized seizures to the anterior insular cortex prior to her typical clinical manifestations. Surgical resection of the insular and frontal-lobe network resulted in seizure freedom. We propose that the anterior insular cortex should be a site of investigation during pre-surgical phase 2 evaluation in patients exhibiting the chapeau de gendarme sign during focal seizures.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Chapeau de gendarme, Ictal pouting, Insula, Focal, SEEG

Highlights

-

•

Chapeau de gendarme seizures or ictal pouting could have insular lobe involvement at electrical seizure onset.

-

•

Phase 2 investigation should include insular monitoring when assessing for this kind of seizures.

-

•

Pediatric population could also have chapeau de gendarme or ictal pouting seizures.

-

•

Ripples were associated with epileptogenicity in insular cortex requiring resection.

1. Introduction

Frontal lobe seizures constitute nearly 30% of focal neocortical seizures [1] but remain difficult to characterize due to their complex semiology, large surface area and electrophysiological patterns [2]. One localizing sign that has been purported for frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) is a characteristic down turning of the mouth into a deep frown, known as ictal pouting or ‘chapeau de gendarme’ (CdG) sign. While the CdG sign is not frequently seen, researchers and clinicians have used it to localize the seizure onset zone (SOZ) to the frontal lobe [[3], [4], [5]]. Due to the complexity of connections with the frontal lobe, however, other regions may initiate epileptogenic networks with complex propagations to the frontal lobe thereby resulting in false localizations for this unique semiological finding.

One other region of interest for CdG initiation is the insula lobe. The insula has a multitude of connections with regions throughout the brain, including the frontal lobes in addition to the limbic system and the temporal- and parietal lobes. While poorly understood until recently, the insula appears to have a diverse array of functions that serves as a network hub to coordinate cognitive domains [6]. Of interest, the insula appears to be involved in feelings including disgust and fear [7,8], two such emotions that have been associated with the CdG sign in frontal lobe seizures. When the insula was sampled in one study, it was included in epileptic network of focal seizures associated with the CdG sign [3]. Herein, we present the case of a 17- year-old female who had frequent focal motor seizures since the age of six years with ictal semiology including the CdG sign but with electrographic origin in the insula delineated by stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG).

2. Case

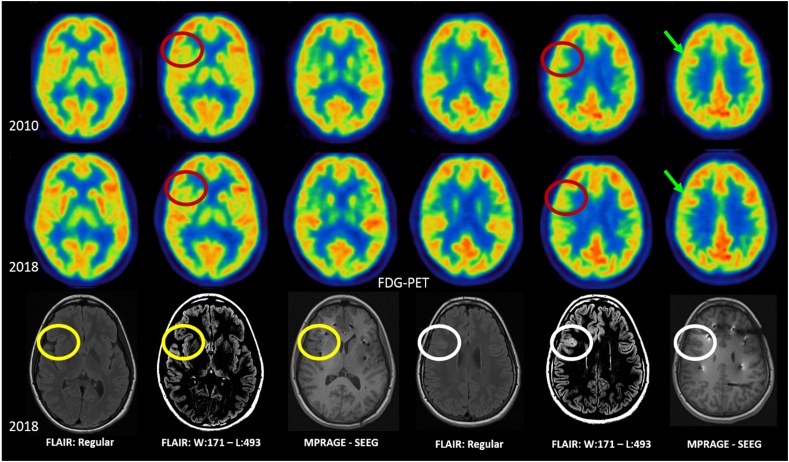

The patient first presented to medical attention at the age of six years with new onset seizures lasting between 60 to 90 s and occurring up to 15 times per day. Semiology included a CdG sign, head and eye deviation to the left, lifting of the head off the bed, apparent generalized stiffening of the body, and fear. Twenty-one channel standard EEG demonstrated seizure onset in the anterior head region with interictal epileptiform activity over the right frontal area, suggesting right frontal onset seizures. Hypometabolic posterior right frontal and anterior insular region was observed on FDG-PET (Fig. 1). The patient was diagnosed with non-lesional focal epilepsy and treated with antiseizure drugs. In retrospective when reviewing imaging following surgical resection, brain MRI showed an area not previously identified that was suspicious for focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) in the right fronto-opercular area (Fig. 1). Surgery was not pursued at this time as she responded well to medication.

Fig. 1.

From top to bottom rows, axial slides of fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) denotes regions of hypometabolism (red circles) inferior to regions with normal metabolism (green areas). Brain MRI was performed in 2018 with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) in regular and narrow window settings and magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequences during stereo electroencephalography with electrodes placed into the insular and orbito-frontal regions. The brain MRI was initially interpreted as normal (yellow circles). However, in retrospective, after pathology results were available, a lesion was visible in the right fronto-opercular area (white circles) seen as an area of increased cortical FLAIR signal. The lesion was more conspicuous with narrow window settings which improved gray-white matter contrast.

The patient's past medical history was unremarkable and she was reaching appropriate developmental milestones over time with the exception of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identify by neuropsychological assessment. Her family history was unremarkable for any contributing causes. No neurological deficits or dysmorphic features were evident on physical exam.

Over the years, antiseizure medication changes were required to control her epilepsy due to occasional seizure relapse, including courses of lamotrigine, lacosamide, levetiracetam and clobazam. At the age of 15 years, however, her focal motor seizures became drug-resistant and a discussion of potentially pursuing epilepsy surgery was initiated. Long-term video-EEG monitoring was performed at that time with seizures captured that were non-localized and interictal epileptiform discharges observed maximally in the right frontal region. Seizure semiology remained relatively constant since her initial presentation. Brain interictal single photon emission computed tomorgraphy (SPECT) showed multi focal areas of hypoperfusion without clear predominance and ictal SPECT was unable to be obtained. An interictal FDG-PET demonstrated stable areas of mild hypometabolism in the right hemisphere. New hypometabolic areas were present in the nasofrontal region and right anterior-inferomedial temporal lobe when compared to a previous FDG-PET done 8 years prior. Despite later delineating a lesion in the right fronto-opercular area the FDG-PET showed normal metabolism (Fig. 1). Because the brain MRI was initially found to be non-lesional, SEEG was proposed.

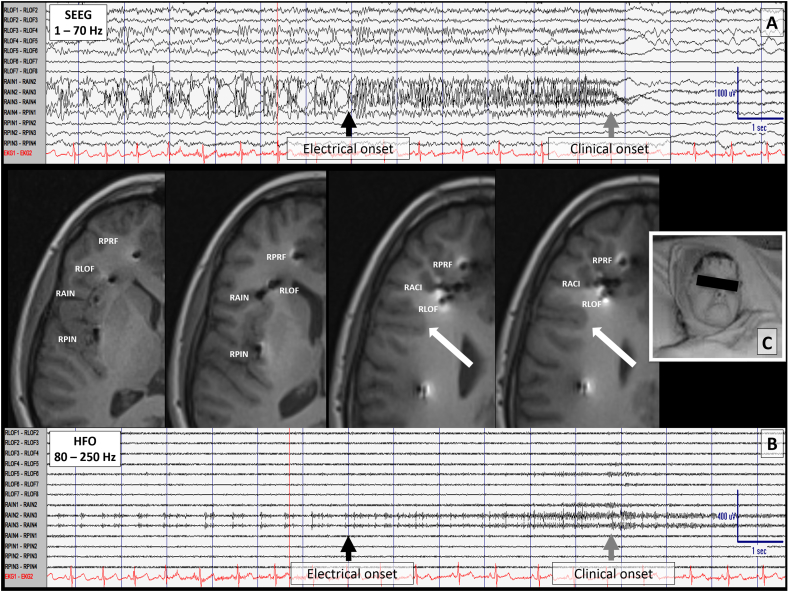

Invasive monitoring was performed with bilateral frontal and anterior insular SEEG electrodes (Fig. 2). SEEG recorded nine brief focal motor seizures without impaired awareness demonstrating the CdG sign. SEEG revealed seizure onset in the right anterior insular (RAIN) cortex. Ripples were detected ranging from 87 Hz to –113 Hz linked with spikes and polyspikes-and-slow waves at onset (Fig. 2.; RAIN contacts 1–4) followed a few seconds later by desynchronized activity in the right lateral orbitofrontal (RLOF) region, and to a lesser extent in the anterior and middle cingulate region during her clinical seizure (Fig. 2.; RLOF contacts 1-6). SEEG findings localized to the anterior insula as the SOZ with a diffused network including right frontal anterior-middle cingulate and orbital-frontal cortex. During cortical mapping, a 12 s electrographic seizure was provoked in the RAIN electrodes (contacts 2-4) as a result of RLOF (contacts 6-7) stimulation but this was not reproducible. Frequent after discharges were seen in RLOF (contacts 3-7) when stimulating the RAIN (contacts 2-4) as well as frequent afterdischarges in the RAIN (contacts 2-4) when the RLOF (contacts 5-6) were stimulated just prior to an electroclinical seizure. RLOF was the closest depth to the later identified lesion on brain MRI.

Fig. 2.

Ictal stereo-electroencephalogram (SEEG) recording showing electrode placement in the right insula and lateral orbitofrontal region. Focal cortical dysplasia (type IIB) is identified by the white arrow in sequential brain MRI axial images. The closest contacts to the lesion are on the right lateral orbito frontal electrode. A) This panel shows an electrographic seizure onset (black arrow) following buidup in the right anterior insula (contacts 1-4). SEEG parameters include: Filters 1- 70 Hz, sensitivity at 50 μV/mm; timebase 30 mm/s; 60 Hz notch filter off. Six seconds later, the seizure involves the frontal lobe (gray arrow) and SEEG becomes more desynchronized at onset of DC shift with focal attenuation. The clinical seizure onset was maximal at contact 6 s but other seizures varied involving contacts 5 to 11 s of the right anterior insula relative to the clinical manifestation. B) This panel shows SEEG settings to enhance ripple bands (Filters 80 –250 Hz, sensitivity 20 μV/mm; timebase 30 mm/s; 60 Hz notch filter off. C) Image of ictal pouting. RACI= right anterior cingulate; RAIN= right anterior insular; RLOF= right lateral orbitofrontal; RMCI= right middle cingulate; RPCI= right posterior cingulate; RPIN= right posterior insular; RPRF= right pre-frontal; RPRM= right pre-motor; RSMA= right supplementary motor area.

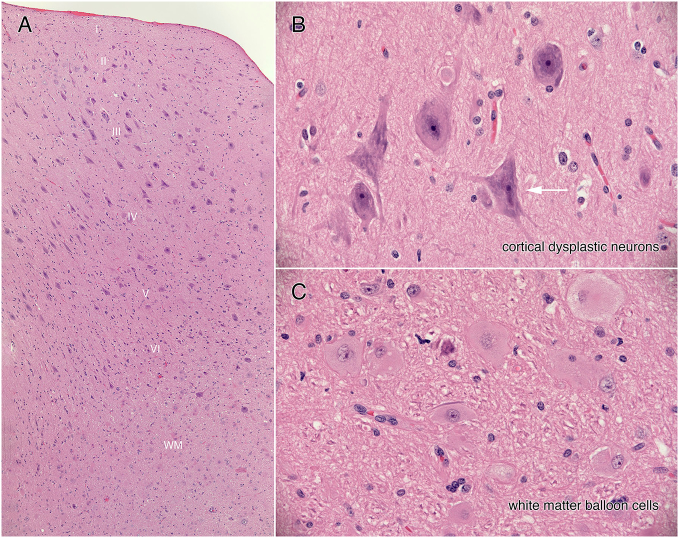

Surgical resection of the right opercular frontal and anterior insular cortex was planned with electrocorticographic guidance (ECoG). ECoG confirmed very active frontal operculum and orbito-frontal cortical tissue helping guide the extent of cortical resection. Pathological examination revealed focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) type IIB in the frontal operculum (Supporting material Fig. 3). Other resected tissue was morphologically normal, aside from a few dysplastic neurons scattered throughout, particularly anterior insular cortex. Following surgery, the patient has remained seizure free for more than 17 months.

Supporting material Fig. 3.

Neuropathology results. Focal Cortical Dysplasia type IIB. All figures are haematoxylin-eosin stained sections from the operculum. Panel A displays a low magnification view of the entire cortical thickness. Notice the large neurons that span but do not respect cortical layers II to VI. Panel B is a high-magnification view of a cluster of dysplastic neurons that have irregular, coarse Nissl substance (basophilic material in cytoplasm) and irregular, sometimes multipolar cells processes (white arrow). In the subcortical white matter (WM in panel A) are many balloon cells (cells with large, eosinophilic cytoplasm and a large nucleus having a prominent nucleolus).

3. Discussion

The ictal semiology and scalp EEG in our patient suggested the right frontal lobe as the symptomatogenic zone [9]. These findings were consistent with previous publications referring to the CdG as a localizing sign arising from the frontal lobe [[3], [4], [5],10]. However, in our case, SEEG recording revealed epilepti form discharges and electrographic seizure onset in the anterior insular cortex prior to the ictal semiology and activation of the frontal lobe, demonstrating that seizures associated with the CdG sign do not always localize the SOZ to the frontal lobe. RLOF electrodes were close to the lesion but not exactly on it and captured low and moderate amplitude epileptiform activity interictally as well as ictally suggesting network involvement but not seizure onset.

Frontal lobe epilepsy has been relatively less well studied compared to other types of epilepsies, in part due to the heterogeneous semiology involved and the highly connected nature of the frontal lobe to other brain regions [11]. One such connection is between the frontal lobe and the insula, particularly the anterior insula [12]. Connections between these two areas allows for intricate viscerosomatic as well as higher order emotional and cognitive processing [6] but differentiating seizure onset zones between these two areas can be difficult. First, seizure semiology can be misleading as it was in this case and for other semiologiies [13.) We also found that focal seizures involving a CdG sign in the semiology does not always localize the SOZ to the frontal lobe. Finally, because of its depth relative to other regions of the brain, the insula cannot be reliably delineated by scalp EEG recordings [14]. Here, SEEG recorded electrographic seizure onset from contacts implanted into the anterior insula prior to involvement of the frontal lobe when the clinical semiology involving the CdG sign became evident. Additionally, the habitual electrographic seizure was elicited when stimulating the RLOF 6-7 electrodes depicting the seizure susceptibility of this region of the epileptic network. These findings support the anterior insula as the SOZ and frontal lobe propagation as the symptomatogenic zone. SEEG recordings have previously identified the insula as the SOZ in patients with focal seizures associated with atypical semiologies falsely presumed to be of frontal lobe origin[15]. In our case, had we not included the insular cortex in the SEEG recording, we would have missed the true onset of the electrographic ictal activity arising from the anterior insular cortex with the result of an incorrect localization of the SOZ to the frontal lobe and potentially suboptimal surgical resection.

The SOZ was electrographically identified here by spikes and polyspikes in addition to prominent high frequency oscillations (HFOs) in the ripple bandwidth on SEEG (Fig. 2). HFOs have been strongly correlated with other interictal markers of epilepsy, do not change locaton over time, and resection of these areas have been correlated with successful epilepsy surgical outcomes [16]. Thus, they are proposed to be a marker of the epileptogenic zone underlying the area of the brain that is necessary and sufficient for seizure initiation. In our case, the location of the ripples identified on SEEG recording were present in the RAIN but not in the RLOF at seizure onset supporting the RAIN as the epileptogenic zone.

Prior reports of patients undergoing epilepsy surgery have found resection of the SOZ in the frontal lobes involving seizures with the the CdG sign have generally resulted in positive outcomes [3,4,10]. Focal seizures involving the CdG sign may arise from the insula as identified in our case or involve the insula [3], or not involve the frontal lobe at all [13]. In the report by Souriti et al. [3], a subset of 3 of 11 patients had electrodes implanted into the insula during SEEG monitoring, all of those patients in that subset showed insular involvement in the epileptic network following frontal onset, mainly in the anterior cingulate cortex. Leitinger et al. [13] reported a case of focal seizures involving the CdG sign without frontal lobe EEG changes, speculated other areas could produce this sign. Had the insula been monitored in that case, Chassoux [17] posited that Leitinger may have found the insula to be the EZ – our findings provide support to this hypothesis.

We now recommend incorporating depth electrodes in the anterior insula during SEEG monitoring in patients with focal seizures involving the CdG sign to characterize the extent of the SOZ and epileptic network. In our patient, surgical resection of the anterior insula, frontal operculum and orbitofrontal cortex resulted in an Engel class 1A outcome. When epilepsy surgery is appropriate for patients involving similar semiology, resection may limit the involvement and extent of the epileptic network and result in seizure freedom

Disclosure

None of the authors has anything to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Ethical statement

Verbal and written consent for publication was obtained from the patient and her parents according to Alberta Children's Hospital policies and data protection and privacy laws.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

References

- 1.Manford M, Hart YM, Sander JW, Shorvon SD. The national general practice study of epilepsy. The syndromic classification of the International League Against Epilepsy applied to epilepsy in a general population. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:1911–1917. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530320025008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonini F, McGonigal A, Trébuchon A. Frontal lobe seizures: from clinical semiology to localization. Epilepsia. 2014;55:264–277. doi: 10.1111/epi.12490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souirti Z, Landré E, Mellerio C, Devaux B, Chassoux F. Neural network underlying ictal pouting (“chapeau de gendarme”) elipepsy. Epilepsy. Behaviour. 2014;37:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan YL, Muhlhofer W, Knowlton R. Pearls and oy-sters: the chapeau de gendarme sign and other localizing gems in frontal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2016;87:e103–e105. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayakawa J, Kubota M. Ictal pouting: kabuki visage or chapeau de gendarme? Pract Neurol. 2018;18:410–412. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2017-001847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and function of the human insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;34:300–306. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calder AJ, Keane J, Manes F, Antoun N, Young AW. Impaired recognition and experience of disgust following brain injury. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1077–1078. doi: 10.1038/80586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan Y, Duncan NW, de Greck M, Northoff G. Is there a core neural network in empathy? An fMRI based quantitative meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:903–911. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenow F, Lüders H. Presurgival evaluation of epilepsy. Brain. 2001;124:1683–1700. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.9.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koc G, Bek S, Gokcil Z. Localization of ictal pouting in frontal lobe epilepsy: a case report. Epilepsy Behav Case Report. 2017;8:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Muircheartaigh J, Richardson MP. Epilepsy and the frontal lobes. Cortex. 2012;48:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaziri J, Tucholka A, Girard G. The corticocortical structural connectivity of the human insula. Cereb Cortex. 2017:1216–1228. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leitinger M, Höfler J, Deak I. “Chapea de gendarme” - a frontomesial ictal sign? Epilepsy Behav. 2015;44:258–259. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sala-Padro J, Fong M, Rahman Z. A study of perfusion changes with insula epilepsy using SPECT. Seizure. 2019;69:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryvlin P, Minotti L, Demarquay G. Nocturnal hypermotor seizures, suggesting frontal lobe epilepsy. Can Originate in the Insula Epilepsia. 2006;47:755–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs J, Staba R, Asano E. High-frequency oscillations (HFOs) in clinical epilepsy. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;98:302–315. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chassoux F. Reply to the letter to the editor “‘Chapeau de gendarme’: a fronto-mesial ictal sign?” by Leitinger et al. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;44:260. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]