Abstract

Background

To quantify image quality and radiation doses in regions adjacent to and distant from bismuth shields in computed tomography (CT).

Methods

An American College of Radiology accreditation phantom with four solid rods embedded in a water-like background was scanned to verify CT number (CTN) accuracy when using bismuth shields. CTNs, image noise, and contrast-to-noise ratios (CNRs) were determined in the phantom at 80–140 kVp. Image quality was investigated on image portions in the zones adjacent (A zone) to and distant (D zone) from a bismuth shield. Surface radiation doses were measured using thermoluminescent dosimeters. Streak artefacts were graded on a 3-point-scale.

Results

Changes in CTN caused by a bismuth shield resulted in changes in X-ray spectra. CTN changes were more apparent in the A zone than in the D zone, particularly for a low tube voltage. The degrees of CTN changes and image noise were proportional to the thickness of the bismuth shields. A 1-ply bismuth shield reduced surface radiation doses by 7.2%–15.5%. The overall CNRs were slightly degraded, and streak artefacts were acceptable.

Conclusions

Using a bismuth shield could result in significant CTN changes and perceivable artefacts, particularly for a superficial organ close to the shield, and is not recommended for quantification CT examinations or follow-up CT examinations.

Keywords: Computed tomography, Radiation protection, Bismuth shielding, Quantification analysis, Image quality

At a glance of commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Using an in-plane bismuth shield is an effective method to reduce superficial organ doses of patients undergoing CT examinations. To quantify image quality and radiation doses in regions adjacent to and distant from bismuth shields can help operators to select appropriate combination of shields.

What this study adds to the field

We quantified changes in CT image quality parameters (CTN, image noise, and CNR) and radiation doses caused by external bismuth shields. Using shields are recommended as the suspicious diagnosis region distant from a bismuth shield, but not recommended for quantification-purposed CT examinations, such as calcification, bone mass density, and follow-up scans.

The increased use of computed tomography (CT) examinations, which currently account for more than 50% of all medical exposures, resulted in high radiation doses to patients [1]. Routine CT examinations, such as head, thoracic, and abdominal scans, and specific examinations for diagnosing coronary artery disease and screening lung cancers contribute to the majority of medical exposures [2]. Superficial and radiosensitive organs, such as the eyes, thyroid, and breast, are often directly exposed during routine head, neck, or chest CT examinations. However, these radiosensitive organs are not imaged primarily for diagnosis. The radiation dose to radiosensitive organs may increase the lifetime relative risk of carcinogenesis [2].

Automatic exposure control (AEC) was introduced to modulate the tube current on the basis of patient size and attenuation to reduce radiation exposure to a patient while maintaining consistent image quality [3]. However, superficial organs, such as the eye lens, thyroid, and breast, do not benefit from AEC scans. Organ-based tube current modulation (OB-TCM), an advanced AEC technique, can be used to reduce the radiation dose to these superficial organs during CT scans [4], [5], [6], [7]. However, this technique is valid only for certain manufacturers’ products. Nikupaavo et al. used the gantry tilt method to reduce the radiation dose to the eye lens during routine head CT scans [8]. When lenses are only partially exposed in the scanning range, OB-TCM or bismuth shields can be useful for reducing the radiation dose to the lens.

Using an in-plane bismuth shield is an alternative method, and it can be suitable for all types of CT scanners. When an X-ray tube is above a patient, the X-ray beam penetrates the bismuth shield first and then the patient's body. Therefore, the intensity of the X-ray beam can be reduced by a bismuth shield. The bismuth shield was used in patients undergoing routine CT examinations with acceptable image noise and overall image quality without interfering with the diagnostic accuracy [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. The effect of breast thickness on bismuth shielding was discussed in Revel's study [15]. Studies opposing against the use of bismuth shields during CT scans have reported that a bismuth shield caused changes in CT number (CTN) accuracy and increased image noise and streak artefacts [6], [16], [17], [18].

Previous studies pointed out that these changes depend on the relative position between the region of interest (ROI) and the shield. However, quantification changes occurring in the region adjacent to a bismuth shield (A zone) or in the region distant from a bismuth shield (D zone) have not been assessed. Moreover, the effects of a bismuth shield on the quality of CT images of materials that resembled different types of tissues, such as fluids, adipose tissue, calcified tissue, bone, and air. Hence, the present study proposes to quantify changes in CTNs, noise, and contrast-to-noise ratios (CNRs) for five tissue-mimicking materials for bismuth shields of different thicknesses and for positions relative to these shields during CT scans. In addition, we assessed the amounts of dose reduction when using bismuth shields of different thicknesses during CT scans.

Materials and methods

CT acquisition protocols

Helical CT scans were performed using a 64-slice scanner (Sensation 64, Somatom, Siemens Medical Systems, Germany) and the following abdominal CT scan parameters: tube voltage, 120 kVp; effective tube current–time product, 100 mAs; rotation time, 0.5 s; detector configuration, 64 × 0.625 mm; 5-mm image reconstruction; and soft-tissue reconstruction kernel (B30f) with the filtered backprojection reconstruction. Three other tube voltages (80, 100, and 140 kVp) were used to compare the image contrast.

Image quality phantom and bismuth shields

We scanned the American College of Radiology (ACR) CT Accreditation phantom (Gammex RMI, Middleton, WI). This phantom consists of four modules designed to test various aspects of CT image quality, including CTN accuracy, uniformity of CTN, and high- and low-contrast resolutions. The length of each module in the z direction is 4 cm, and the diameter of each module is 20 cm. Prior to scanning, the phantom was centered in the x, y, and z planes. The first module of the phantom with four solid rods embedded in a water-like background was scanned to verify CTN accuracy with and without a bismuth shield. Nominal CTNs for polyethylene, water, acrylic, bone, and air provided by ACR CT phantom specifications for a voltage of 120 kVp were −107 to −84 HU, −7 to +7 HU, 110 to 135 HU, 850 to 970 HU, and −1005 to −970 HU, respectively [19].

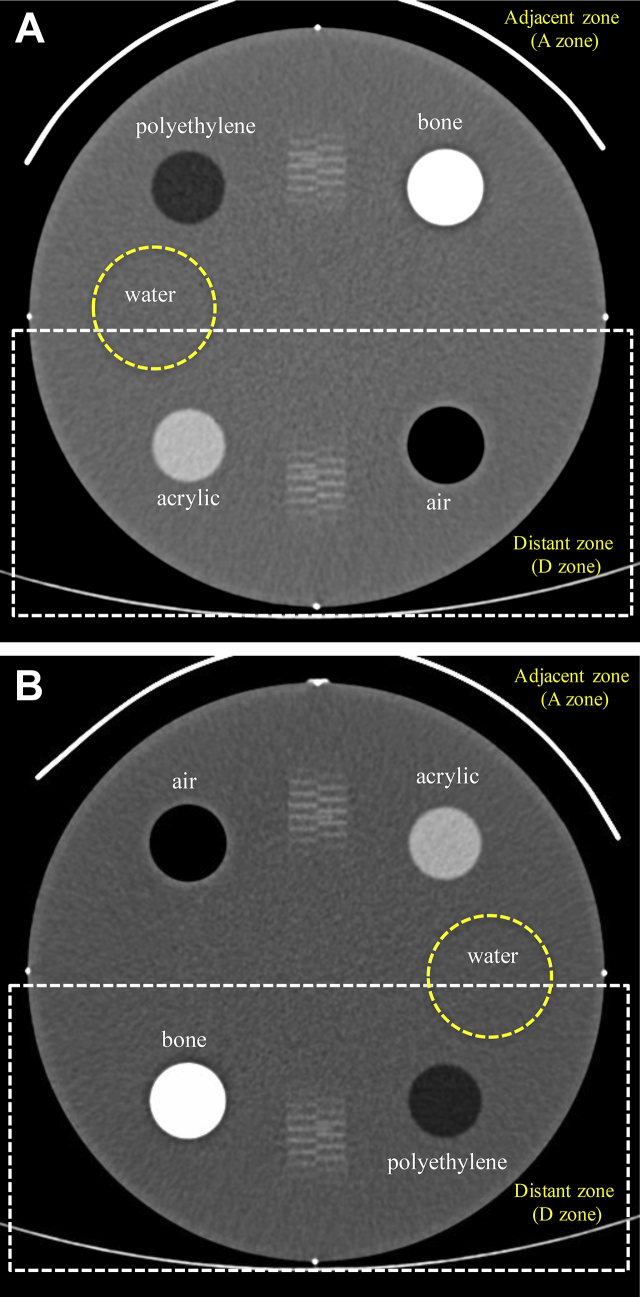

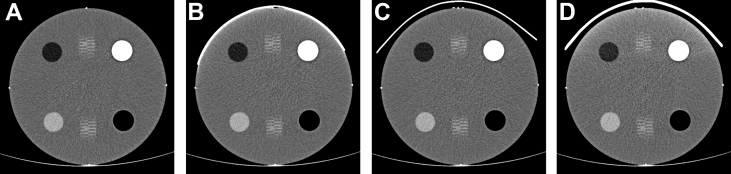

Bismuth shields (3.4 g/cm2 of bismuth per layer, AttenuRad, F&L Medical Products, Vandergrift, Pa) were used in our experiments. We placed 1-ply to 6-ply bismuth shields over the phantom. Bismuth shields were placed over 1- and 2-cm-thick foam rubber sheets that were used to lift the shields away from the phantom to reduce the potential for streak artefacts [13], [20]. The ACR phantom was scanned two times. Fig. 1A shows the CT image of the first scan. The objects of polyethylene and bone were in the zone adjacent to bismuth shielding (A zone). The objects of acrylic and air were in the zone distant from bismuth shielding (D zone). The phantom was then rotated 180° to acquire the second image (Fig. 1B). The positions of the objects relative to bismuth shielding were changed. The effects of relative positions between shields and solid rods on image quality were investigated.

Fig. 1.

American College of Radiology computed tomography accreditation phantom. The effects on radiation dose and image quality were evaluated separately in two zones: adjacent zone (A zone) and distant zone (D zone). High-sensitivity thermoluminescent dosimeters (arrows) were irradiated with and without bismuth shielding by using different tube voltages. Foam rubber sheets were used to reduce scatter radiation and streak artefacts. All computed tomography images were set at a soft-tissue window setting (400/40 HU).

Quantitative image analysis

The CTNs and image noise of four tissue-mimicking materials and the water-like background were determined in 10 × 10 mm2-square ROIs at the A and D zones (Fig. 1). CTN was calculated as the mean value of an ROI and averaged over six adjacent images along the z direction. Image noise (σ) was defined as the standard deviation of an ROI in the water-like background.

A change in CTN caused by a bismuth shield was expressed as ΔCTN:

| ΔCTN = CTNs − CTNus, | (1) |

where CTNs was CTN acquired using a bismuth shield and CTNus was CTN acquired without a bismuth shield.

The difference in image noise caused by a bismuth shield was expressed by

| Δσ = σs − σus, | (2) |

where σs was the background noise with a bismuth shield and σus was the background noise without a bismuth shield.

The CNR was expressed by

| (3) |

where CTNx was the CTN of each solid rod, CTNw was CTN in the water-like background, and was the noise in the water-like background.

Qualitative image analysis

Three radiological technologists with 8–12 years of experience independently graded streak artefacts in each image acquired with a bismuth shield and a 1-cm foam rubber sheet. These technologists were blinded to image acquisition protocols. All images were evaluated at a soft-tissue window setting (window, 400; level, 40). The degree of streak artefacts for each protocol was rated using a 3-point scale: 1, streak artefacts present, affecting visibility and interfering with depicting adjacent structures; 2, streak artefacts present without affecting visibility or interfering with depicting adjacent structures; and 3, absence of streak artefacts. A score of 2 was considered acceptable for each protocol.

Radiation dose measurements

To measure radiation exposure during CT scans, we used high-sensitivity thermoluminescent dosimeter (TLD) chips made of LiF:Mg, Cu, and P (TLD-100H, Harshow, OH, USA) with a diameter of 4.5 mm and a thickness of 0.8 mm. TLD chips with homogeneity (sensitivity variation) within 3% of the mean response were selected using a monoenergetic beam (137Cs, Standard Laboratory, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan). The dose–response linearity of TLD chips was tested over the range from a few μGy to a few mGy; these results showed a good linear fit (R2 = 0.99). The energy response was examined at 120 kVp X-ray relative to 137Cs and was equal to 0.95. Dose estimations from these individually calibrated TLD chips had uncertainties within ±5%.

TLD chips were placed on the top of the phantom to measure surface radiation doses with and without a bismuth shield. The percentage reduction in the radiation dose was expressed by

| (4) |

where the percentage was the radiation dose reduction factor, Ds was the radiation dose with a shield, and Dus was the radiation dose without a shield.

Statistical analysis

Results for continuous variables represented as means ± standard deviations were compared using Student's t test. Results for ordinal variables of image artefacts represented as medians with interquartile ranges were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica software (Statistica, version 7.1, StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Foam rubber effects

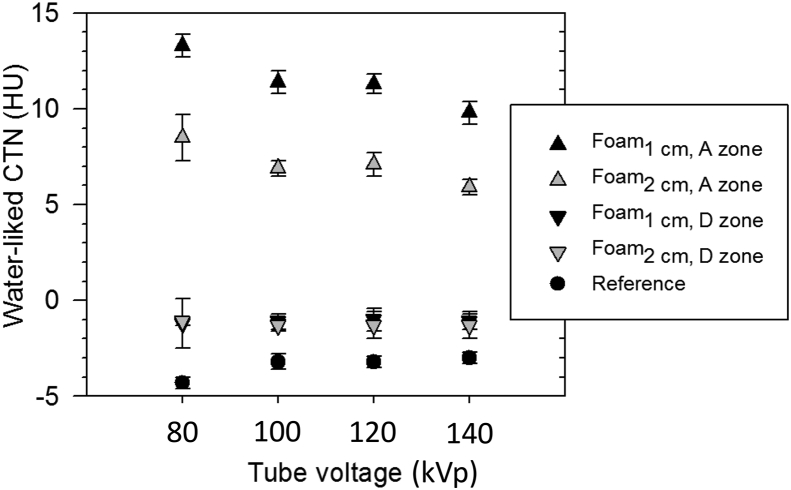

The CTNs of the water-like background increased when a bismuth shield was used during a CT scan. Compared with CTNs acquired without a bismuth shield, CTNs acquired with a 3-ply bismuth shield were higher and more obvious when a low-energy tube voltage was used (Fig. 2). A foam rubber sheet was used to lift the bismuth layer away from the phantom surface to reduce the change in CTN. Differences in CTN caused by a bismuth shield with a foam rubber sheet in the A zone ranged from 12.9 to 17.6 HU at four tube voltages. These changes in CTN could be reduced using a 2-cm foam rubber sheet. The difference in CTN in the D zone (1.9–3.1 HU) was lower than that in the A zone. In subsequent experiments, we used a 1-cm foam rubber sheet with different bismuth shield layers, because the commercial package had bismuth layers that were in contact with a 1-cm foam rubber sheet.

Fig. 2.

Changes in CTN affected by the thickness of foam rubber. A 3-ply bismuth shield with 1-cm (black triangles) and 2-cm (gray triangles) foam rubber sheets placed over the phantom surface. Water CTN with (triangles) and without (circles) a bismuth shield for the A zone (△) and the D zone (▼) were measured in the phantom background. Measured CTN with a bismuth shield and foam rubber at four voltages were compared with those without a shield (reference scan: ●). Error bars indicate standard deviations in CTN in six continuous images.

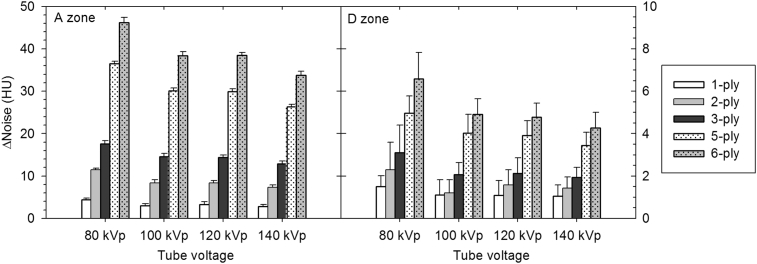

Image noise

Increasing the layers of a bismuth shield resulted in more image noise (Fig. 3). Changes in image noise in the A zone (2.8–46.2 HU) were greater than those in the D zone (1.0–4.9 HU). Using a low-energy tube voltage in combination with a thick bismuth shield resulted in severe image noise and streak artefacts. The maximum value of the change in noise (46.2 HU) was observed in images with 6-ply bismuth shields at 80 kVp. In the A zone, the change in noise was <5 HU when a 1-ply bismuth shield was used at all kVp settings. In the D zone, changes in noise were all <5 HU, except when a 6-ply bismuth shield was used at 80 kVp.

Fig. 3.

Noise differences with and without a shield in the A zone and the D zone. Noise differences with 1-ply to 6-ply bismuth shields at four voltages are shown in each zone. Error bars indicate standard deviations in image noise in six continuous images.

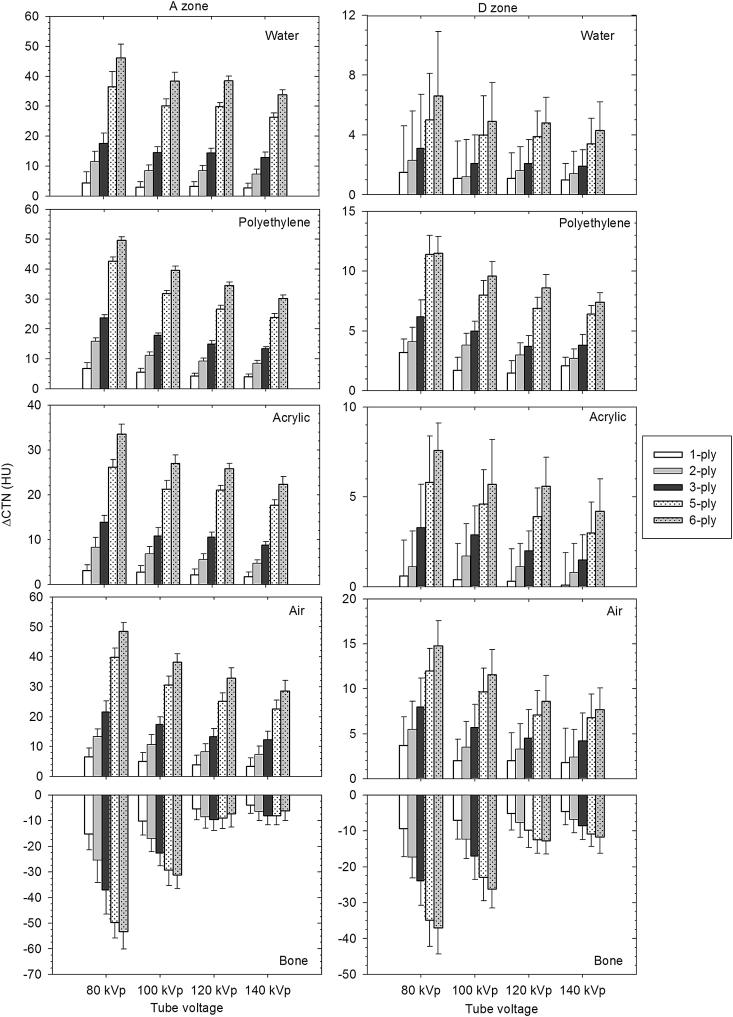

Changes in CTN with bismuth shields

Increasing the layers of bismuth shielding resulted in a high ΔCTN (Fig. 4). The ΔCTNs for the five objects at 120 kVp increased with the number of shielding layers used in the A zone (water-like background: 3.3–38.5 HU; polyethylene: 4.3–34.5 HU; acrylic: 2.2–25.8 HU; air: 3.4–48.5 HU; and bone: −5.4 to −9.6 HU). These effects were not obvious in the D zone (water: 1.1–4.8 HU; polyethylene: 1.5–8.6 HU; acrylic: 0.3–5.6 HU; air: 2.0–8.6 HU; and bone: −5.1 to −12.8 HU). These changes were conspicuous, particularly when a low-energy tube voltage was used. The maximum ΔCTNs acquired with a 6-ply bismuth shield at 80 kVp were 49.6 HU and −53.2 HU, respectively, for polyethylene and bone. The CTN of the bone decreased when bismuth shields were used.

Fig. 4.

Differences in CTN with and without a shield in the A zone (left column) and D zone (right column). Differences in CTN for five materials (water, polyethylene, acrylic, air, and bone) with 1-ply to 6-ply bismuth shields at four tube voltages are shown in each zone. Error bars indicate standard deviations in image noise in six continuous images.

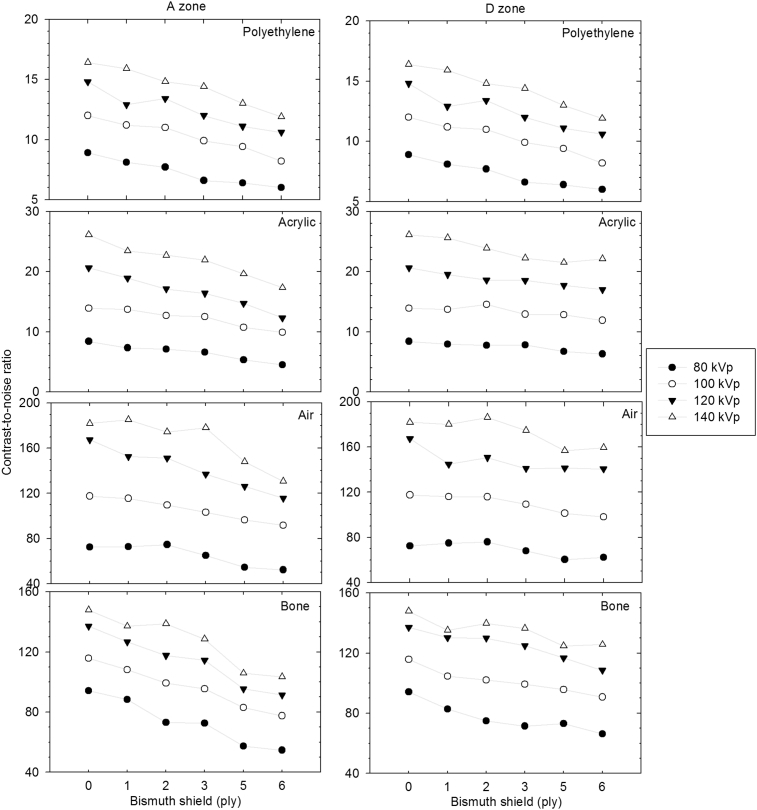

CNR

The CNR slightly decreased when bismuth shields were used during CT scans (Fig. 5). The CNR values acquired without a shield at 120 kVp in the A zone were 14.8, 20.6, 167.4, and 137.0 for polyethylene, acrylic, air, and bone, respectively. Percentage reductions in the CNR caused by shielded scans at 120 kVp ranged from 10.5 to 40.0% for polyethylene, 9.0–69.0% for acrylic, 9.9–45.4% for air, and 10.0–52.2% for bone. Increased tube voltages resulted in smaller CNR changes in these four objects.

Fig. 5.

CNRs with and without a shield in the A zone (left column) and D zone (right column). CNRs for five materials (water, polyethylene, acrylic, air, and bone) with 1-ply to 6 -ply bismuth shields at four tube voltages (80 kVp: ●; 100 kVp: ○; 120 kVp: ▼; 140 kVp: △) are shown in each zone.

Subjective image quality

The degrees of streak artefacts in CT images acquired using bismuth shields are listed in Table 1. Image quality when considering artefacts generated with a 1-ply bismuth shield at tube voltages greater than 100 kVp was acceptable (grade values of 2 and 3). In scans acquired using a tube voltage of 80 kVp, many artefacts were generated when bismuth shields were used, and these artefacts interfered with diagnostic quality (Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Subjective image quality scores and frequency of scores for image artefacts.

| 80 kVp | 100 kVp | 120 kVp | 140 kVp | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-ply | 1a (19/8/0) | 2a (0/17/10) | 3 (0/3/24) | 3 (0/1/26) | <0.001 |

| 3-ply | 1a (23/4/0) | 2a (0/27/0) | 3 (0/9/18) | 3 (0/2/25) | <0.001 |

| 4-ply | 1a (23/4/0) | 2a (0/27/0) | 3 (0/4/23) | 3 (0/2/25) | <0.001 |

Data are medians with the frequency of each score in parentheses.

Statistical results showed significant differences between each kVp.

Fig. 6.

Effects of streak artefacts with and without shields. Streak artefacts in a soft-tissue window (400/40 HU) after shielding were detected at a low energy of 80 kVp. (A) A computed tomography image without a bismuth shield. (B) A streak artefact was observed at the interface between a 1-ply bismuth shield and the phantom surface. (C) The streak artefact was reduced using a 1-ply bismuth shield and with a 1-cm foam rubber sheet. (D) Increased streak artefacts were observed when a 3-ply shield was used.

Radiation dose

The measured radiation dose at the phantom surface could be reduced using a bismuth shield (p < 0.001; Table 2). Reductions in the measured dose were 7.2%, 15.7%, 11.1%, and 15.5% with a 1-ply shield at 80, 100, 120, and 140 kVp, respectively (Table 2). A progressive decrease in the radiation dose was achieved by adding multiple-ply shields. Dose reductions achieved using 2-ply to 6-ply shields ranged from 31.6% to 59.7% for 80 kVp, 29.6%–55.9% for 100 kVp, 20.6%–50.5% for 120 kVp, and 24.3%–47.0% for 140 kVp.

Table 2.

Percent dose reduction acquired using bismuth shields.

| 1-ply | 2-ply | 3-ply | 4-ply | 5-ply | 6-ply | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 kVp | 7.2 | 31.6 | 42.0 | 42.4 | 52.1 | 59.7 |

| 100 kVp | 15.7 | 29.6 | 35.8 | 40.3 | 51.2 | 55.9 |

| 120 kVp | 11.1 | 20.6 | 26.6 | 33.9 | 43.5 | 50.5 |

| 140 kVp | 15.5 | 24.3 | 35.2 | 36.3 | 42.3 | 47.0 |

Discussion

McCollough and Wang's group have discouraged the use of bismuth breast shields for reducing radiation doses during CT scanning because breast shields wasted radiation already delivered to a patient and reduced image quality and CTN accuracy [6], [17], [18], [21]. However, changes in image quality parameters, such as the CTN, image noise, and CNR, in various human tissues based on their relative positions to bismuth shields were not analyzed in previous studies. In the present study, we quantified the relationship between the bismuth shields of different thicknesses and the positions of materials relative to these shields.

Image noise increased and streak artefacts were observed when bismuth shields were used over the phantom surface. When the distance between a shield and a phantom surface is increased, there is a reduction in the generation of streak artifacts [22], [23], [24], [25]. The results of this study are in agreement with those of previous studies. However, although image noise and artefacts could be reduced using foam rubber to increase the distance between a shield and a phantom, image noise still increased with bismuth shielded scans.

Wang et al. reported an increased image noise of 6.0 HU with a 1-ply eye shield even when the distance between a shield and the phantom surface was increased [6]. Kim et al. concluded that using a bismuth shield in combination with low-dose thoracic CT resulted in increased noise in the chest wall, although this region is not crucial for lung cancer screening [7]. In addition, they reported that increased noise in an anterior lung field may result in a misdiagnosis in detecting faint, small nodules when combining a bismuth shield and low-dose thoracic CT examination.

Based on the effects of a bismuth shield and its relative position, we measured an increased water noise of <7 HU in the D zone even when a 6-ply bismuth shield was used for an 80-kVp scan. To make a diagnosis in the A zone, the thickness of a bismuth shield should not be more than 2 ply (noise of 8–12 HU with four voltages used), because image noise may affect diagnostic accuracy, particularly for low-contrast detection. Although the acceptable image noise depends on diagnostic tasks, the noise level of 8–12 HU was acceptable in neck and thoracic CT examinations [9], [15], [33].

The effect on CTNs when using different attenuating materials was quantified using clinical CT tube voltages. Previous studies have indicated that CTNs artificially increased when bismuth shields were used, because bismuth shields cause the beam hardening and make the reconstruction algorithm to report wrong CT numbers. CTNs increased by 18–33 HU in strap and sternocleidomastoid muscles during neck scans and by 20 HU in the chest wall during thoracic scans, which were especially pronounced in the A zone [6], [7], [26], [27]. The tissue-mimicking materials that we used, namely water, polyethylene, and acrylic, are usually used as substitutes for fluids, adipose tissue, and calcification or stone, respectively. When these materials are inserted into the ACR phantom, they can be used for quantitative analysis in diagnostic radiology.

If CTNs increase when a bismuth shield is used, normal fluid might be misidentified as bleeding or an abscess. Adipose tissue might be described as fibrosis (lipoma), especially during liver CT examinations. Increased CTNs in calcification can result in overestimation of calcium scores during coronary examinations. Changes in CTNs in the air and bone may not be a problem because these objects are high-contrast materials on CT images. However, accuracy might be questionable when CT images are used to quantify bone densitometry [28].

A low tube voltage (80 kVp) is suggested for pediatric CT examinations to reduce unnecessary radiation doses to children [13], [24], [25], [29], [30], [31], [32]. However, we observed a shift in CTNs and increased image noise when an in-plane bismuth shield was used during 80-kVp CT scanning, which indicated a severe problem. The overall image quality based on the CNR also degraded when a bismuth shield was used during 80-kVp scanning. For quantification-purposed CT imaging, the shift in CTNs caused by bismuth shields may result in a misdiagnosis. Therefore, the use of bismuth shields during low-tube-voltage pediatric CT scans should be considered carefully, especially when CT images are used for quantification. To reduce radiation doses to pediatric patients, the OB-TCM technique and a fixed low tube current-time product determined by TCM techniques may be an alternative [33].

In this study, the CNR decreased slightly when a bismuth shield was used during CT scans because of changes in CTNs and increased image noise. These slight degradations were not reflected in our visual assessments. More attention should be paid to using bismuth shields during CT examinations for quantification purposes.

Dose reductions to the breast with bismuth shielding for adults have been reported to be in the range of 30%–59%, which is similar to dose reductions of 20.6%–50.5% with shields at 120 kVp observed in our study [10], [34], [35]. Dose reductions at 100 kVp were higher than those at 80, 120, and 140 kVp because the effective photon energy of a 100-kVp X-ray beam is well below the bismuth K-edge (Z = 83 and K-edge energy = 90.5 keV) [36]. Using a bismuth shield during CT scans is an effective method for reducing radiation doses to patients, although image noise and CTN accuracy might be affected. Global reduction of the tube current and OB-TCM techniques are alternative methods for reducing radiation doses without degrading CTN accuracy [6], [18], [33], [35]. However, other concerns arise when using OB-TCM. The OB-TCM technique can lead to increased doses to the spine and lungs, and these increased dose can result in a high radiation risk to the lungs and spine when X-ray tube currents are increased to a patient's posterior region during thoracic CT scans [37], [38]. The present study has some limitations. A phantom was used to quantify the effects of in-plane shielding on CT scans. However, a real patient body is oval in shape with a longer lateral dimension. The phantom only provides an air cavity for quantifying the shift in CTN, and it could not be equalized to the change in the chest wall. Furthermore, experiments were performed only in a single-vendor CT scanner.

In the present study, we quantified changes in CT image quality parameters (CTN, image noise, and CNR) and radiation doses caused by external bismuth shields. Bismuth shields can effectively reduce radiation doses to superficial radiosensitive organs when performing CT scans. For routine CT examinations, such as head, neck, and thoracic scans, using bismuth shields can reduce doses to the eye lens, thyroid, and breast without interfering with the diagnostic accuracy if these radiosensitive organs are not in diagnostic regions. For quantification-purposed CT examinations, such as calcification, bone mass density, and follow-up scans, the use of bismuth shields is discouraged because these shields can change diagnoses and treatment procedures. These effects of these changes are greater especially when tissues or organs are close to bismuth shields. The use of a bismuth shield should be considered when a pediatric patient undergoes a low tube voltage CT examination and these CT images would be used for quantification analysis.

Conflicts of interest

All auhtors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, R.O.C. (NSC99-2623-E182-003, MOST103-2314-B-182-009-MY2) and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (BMRPA61). The authors thank the Particle Physics and Beam Delivery Core Laboratory of Institute for Radiological Research for help regarding dose assessment.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2019.04.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Schauer D.A., Linton O.W. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements report shows substantial medical exposure increase. Radiology. 2009;253:293–296. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532090494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICRP The 2007 recommendations of the international commission on radiological protection. ICRP publication 103. Ann ICRP. 2007;37:1–332. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soderberg M., Gunnarsson M. Automatic exposure control in computed tomography--an evaluation of systems from different manufacturers. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:625–634. doi: 10.3109/02841851003698206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lungren M.P., Yoshizumi T.T., Brady S.M., Toncheva G., Anderson-Evans C., Lowry C. Radiation dose estimations to the thorax using organ-based dose modulation. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W65–W73. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reimann A.J., Davison C., Bjarnason T., Yogesh T., Kryzmyk K., Mayo J. Organ-based computed tomographic (CT) radiation dose reduction to the lenses: impact on image quality for CT of the head. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36:334–338. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318251ec61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J., Duan X., Christner J.A., Leng S., Grant K.L., McCollough C.H. Bismuth shielding, organ-based tube current modulation, and global reduction of tube current for dose reduction to the eye at head CT. Radiology. 2012;262:191–198. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim Y.K., Sung Y.M., Choi J.H., Kim E.Y., Kim H.S. Reduced radiation exposure of the female breast during low-dose chest CT using organ-based tube current modulation and a bismuth shield: comparison of image quality and radiation dose. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:537–544. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lens dose in routine head CT: comparison of different optimization methods with anthropomorphic phantoms. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:117–123. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y.H., Park E.-T., Cho P.K., Seo H.S., Je B.-K., Suh S.-I. Comparative analysis of radiation dose and image quality between thyroid shielding and unshielding during CT examination of the neck. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:611–615. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yilmaz M.H., Yaşar D., Albayram S., Adaletli I., Ozer H., Ozbayrak M. Coronary calcium scoring with MDCT: the radiation dose to the breast and the effectiveness of bismuth breast shield. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopper K.D. Orbital, thyroid, and breast superficial radiation shielding for patients undergoing diagnostic CT. Seminars Ultrasound, CT MRI. 2002;23:423–427. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(02)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobbs M., Ahmed R., Patrick L.E. Bismuth breast and thyroid shield implementation for pediatric CT. Radiol Manag. 2011;33:18–22. quiz23–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fricke B.L., Donnelly L.F., Frush D.P., Yoshizumi T., Varchena V., Poe S.A. In-plane bismuth breast shields for pediatric CT: effects on radiation dose and image quality using experimental and clinical data. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:407–411. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.2.1800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catuzzo P., Aimonetto S., Fanelli G., Marchisio P., Meloni T., Mistretta L. Dose reduction in multislice CT by means of bismuth shields: results of in vivo measurements and computed evaluation. La Radiol Med. 2010;115:152–169. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revel M., Fitton I., Audureau E., Benzakoun J., Lederlin M., Chabi M. Breast dose reduction options during thoracic CT: influence of breast thickness. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:W421–W428. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huggett J., Mukonoweshuro W., Loader R. A phantom-based evaluation of three commercially available patient organ shields for computed tomography X-ray examinations in diagnostic radiology. Radiat Protect Dosim. 2013;155:161–168. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncs327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geleijns J., Wang J., McCollough C. The use of breast shielding for dose reduction in pediatric CT: arguments against the proposition. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1744–1747. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1808-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCollough C.H., Wang J., Gould R.G., Orton C.G. Point/counterpoint.The use of bismuth breast shields for CT should be discouraged. Med Phys. 2012;39:2321–2324. doi: 10.1118/1.3681014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radiology A.C.O. American College of radiology CT accreditation program 23 testing instructions. https://docplayer.net/2466882-American-college-of-radiology-ct-accreditation-program-testing-instructions.html (Accessed 2018)

- 20.Lee K., Lee W., Lee J., Lee B., Oh G. Dose reduction and image quality assessment in MDCT using AEC (D-DOM & Z-DOM) and in-plane bismuth shielding. Radiat Protect Dosim. 2010;141:162–167. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncq159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCollough C.H., Wang J., Berland L.L. Bismuth shields for CT dose reduction: do they help or hurt? J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8:878–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalra M.K., Dang P., Singh S., Saini S., Shepard J.-A.O. In-plane shielding for CT: effect of off-centering, automatic exposure control and shield-to-surface distance. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:156–163. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antypas E.J., Sokhandon F., Farah M., Emerson S., Bis K.G., Tien H. A comprehensive approach to CT radiation dose reduction: one institution's experience. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;197:935–940. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raissaki M., Perisinakis K., Damilakis J., Gourtsoyiannis N. Eye-lens bismuth shielding in paediatric head CT: artefact evaluation and reduction. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1748–1754. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S., Frush D.P., Yoshizumi T.T. Bismuth shielding in CT: support for use in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1739–1743. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y.H., Park E.-T., Cho P.K., Seo H.S., Je B.-K., Suh S.-I. Comparative analysis of radiation dose and image quality between thyroid shielding and unshielding during CT examination of the neck. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:611–615. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Einstein A.J., Elliston C.D., Groves D.W., Cheng B., Wolff S.D., Pearson G.D.N. Effect of bismuth breast shielding on radiation dose and image quality in coronary CT angiography. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19:100–108. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9473-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bird V.G., Bird V.Y. Radiologic imaging of renal masses. In: Poppel Hendrik Van., editor. Renal cell carcinoma. InTech; Croatia: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai N.K., Liao Y.L., Chen T.R., Tyan Y.S., Tsai H.Y. Real-time estimation of dose reduction for pediatric CT using bismuth shielding. Radiat Meas. 2011;46:2039–2043. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perisinakis K., Raissaki M., Theocharopoulos N., Damilakis J., Gourtsoyiannis N. Reduction of eye lens radiation dose by orbital bismuth shielding in pediatric patients undergoing CT of the head: a Monte Carlo study. Med Phys. 2005;32:1024–1030. doi: 10.1118/1.1881852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukundan S., Frush D.P., Yoshizumi T. MOSFET dosimetry for radiation dose assessment of bismuth shielding of the eye in children. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1648–1650. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coursey C., Frush D.P., Yoshizumi T., Toncheva G., Nguyen G., Greenberg S.B. Pediatric chest MDCT using tube current modulation: effect on radiation dose with breast shielding. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:W54–W61. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Duan X., Christner J.A., Leng S., Yu L., McCollough C.H. Radiation dose reduction to the breast in thoracic CT: comparison of bismuth shielding, organ-based tube current modulation, and use of a globally decreased tube current. Med Phys. 2011;38:6084–6092. doi: 10.1118/1.3651489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geleijns J., Salvado Artells M., Veldkamp W.J.H., Lopez Tortosa M., Calzado Cantera A. Quantitative assessment of selective in-plane shielding of tissues in computed tomography through evaluation of absorbed dose and image quality. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:2334–2340. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yilmaz M.H., Albayram S., Yaşar D., Ozer H., Adaletli I., Selcuk D. Female breast radiation exposure during thorax multidetector computed tomography and the effectiveness of bismuth breast shield to reduce breast radiation dose. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:138–142. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000235070.50055.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roessl E., Proksa R. K-edge imaging in x-ray computed tomography using multi-bin photon counting detectors. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:4679–4696. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/15/020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huda W., Sterzik A., Tipnis S., Schoepf U.J. Organ doses to adult patients for chest CT. Med Phys. 2010;37:842–847. doi: 10.1118/1.3298015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angel E., Yaghmai N., Jude C.M., DeMarco J.J., Cagnon C.H., Goldin J.G. Dose to radiosensitive organs during routine chest CT: effects of tube current modulation. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1340–1345. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.