Abstract

Cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) is highly expressed in immune cells and plays an important role in regulating immune responses. In the current study, we investigated the effects of GW405833 (GW), a specific CB2R agonist, on acute liver injury induced by concanavalin A (Con A). In animal experiments, acute liver injury was induced in mice by injection of Con A (20 mg/kg, i.v.). The mice were treated with GW (20 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min after Con A injection) or GW plus the selective CB2R antagonist AM630 (2 mg/kg, i.p., 15 min after Con A injection). We found that Con A caused severe acute liver injury evidenced by significantly increased serum aminotransferase levels, massive hepatocyte apoptosis, and necrosis, as well as lymphocyte infiltration in liver tissues. Treatment with GW significantly ameliorated Con A-induced pathological injury in liver tissue, decreased serum aminotransferase levels, and decreased hepatocyte apoptosis. The therapeutic effects of GW were prevented by AM630. In cell experiments, we showed that CB2Rs were highly expressed in Jurkat T cells, but little expression in L02 liver cells. Treatment with GW (10−40 μg/mL) dose-dependently decreased the viability of Jurkat T cells and induced cell apoptosis, which was reversed by AM630. In the coculture of Jurkat T cells with L02 liver cells, GW dose-dependently protected L02 cells from apoptosis induced by Con A (5 μg/mL). The protective effect of GW was reversed by AM630 (1 μg/mL). Our results suggest that GW protects against Con A-induced acute liver injury in mice by inhibiting Jurkat T-cell proliferation through the CB2Rs.

Keywords: cannabinoid receptor 2, GW405833, AM630, Concanavalin A, acute liver injury, Jurkat T cells, L02 liver cells

Introduction

Acute liver injury is a severe and acute disease characterized by acute liver cell necrosis. Acute liver injury is mainly caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) in China [1–3]. Within the last few decades, there has been no fundamental breakthrough in the treatment of liver injury caused by HBV or other immune injury [4]. Emerging evidence suggests a new approach, using immunotherapy for the treatment of acute liver injury mediated by T cells [5]. It is known that HBV infection induces acute liver injury by excessively activating T cells to produce a large amount of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and other inflammatory factors, rather than damaging the liver directly [6, 7]. IFN-γ can activate/recruit immune cells, including NK cells, to colonize or gather in the liver to cause inflammation and damage [8]. TNF-α exerts direct hepatocyte toxicity by inducing cell autolysis by binding to specific cell membrane receptors and then it enters cells to promote lysosomal enzyme release [9, 10]. For this reason, inhibition of T cells mediated inflammatory responses has been proposed as a promising therapeutic approach for HBV-induced acute liver injury [11].

The cannabinoid receptors family consists of two subtypes, cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R). The expression level of CB1R in the immune system is low, whereas CB2R is mainly expressed in the cells of the immune system including B cells, NK cells, and T cells [12]. CB2Rs play an important role in modulating immune responses. CB2R-specific agonists have an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the migration and proliferation of T cells, and reducing the release of inflammatory factors including IFN-γ and TNF-α [13]. In mice, the activation of CB2R can inhibit immune rejection after organ transplantation by inhibiting T cells [14]. In addition, the specific activation of CB2R has also been proposed for treating other immune inflammatory-related diseases, such as spinal cord injury, systemic sclerosis, autoimmune uveal retinitis, endotoxin-induced inflammation, and osteoarthritis [14, 15]. Therefore, CB2Rs could be a valuable targeted candidate for the treatment of acute liver injury.

To fulfill this purpose, the selection of a proper CB2 receptor binding and activating ligand is vital because they belong to varied structural classes and display extreme functional selectivity. Among several CB2R-specific agonists, GW405833 (GW) is reported to have the highest binding affinity [16]. Therefore, researchers have attempted to explore its immune regulating potential and the data clearly indicate that it can protect mice from septicemia by blocking extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) and nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB) through activating CB2R [17]. This suggests that the CB2R-specific agonist GW has the potential to be a novel therapeutic drug for treating acute liver injury mediated by T-cell over activation.

The study of Kato and Hegde in rat animal experiments confirmed that concanavalin A (Con A) can damage liver cells by activating T cells to produce IFN-γ, TNF-α, and other cytokines, in which the mechanism of the induction of acute liver injury is similar to that of HBV. In view of the fact that both Con A and HBV-induced acute liver injury are mediated by T cells [18, 19], the establishment of an acute liver injury model with Con A can be used as an effective way to study HBV-induced acute liver injury.

In this study, we verified that GW regulated T cells to protect against the acute liver injury induced by Con A through activating T-cell CB2Rs, and thus our work provides a therapeutic approach to CB2R-mediated modulation in immune-related liver injury.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male BALB/c mice with weights between 20 and 25 g (6–8 weeks old) were used for the animal experiments. Mice were housed and maintained in a standard controlled environment (20–25 °C, 50% ± 5% humidity) with a 12-h dark/light cycle in the Department of Laboratory Animals of Central South University (Changsha, China). All mice were fed with a standard laboratory diet and water. Mice were prepared before and by acclimatizing for at least l week.

Reagents

Con A was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were tested in the clinical laboratory of Xiangya Hospital (Changsha, China). The CB2R agonist GW and antagonist AM630 were purchased from Tocris (Avonmouth, Bristol UK). Antibodies against BAX, BCL-2, and Caspase 3 were purchased from Proteintech (USA), anti-human CB2R antibody was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), and anti-mouse-CB2R antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Anti-Parp antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The anti-actin and anti-tubulin antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China).

Animal treatment

Animals were divided into five groups, control, Con A, Con A plus GW, Con A plus GW and AM630, and Con A plus AM630. The control group was treated with vehicle (saline 2 mL/kg, i.v.) via the tail vein; the Con A group (liver injury group) was treated with Con A (20 mg/kg, i.v.); the Con A plus GW group was treated with Con A (20 mg/kg, i.v.) and GW (20 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min after Con A injection); the Con A plus GW and AM630 group was treated with Con A (20 mg/kg, i.v.) and GW (20 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min after Con A injection) plus AM630 (2 mg/kg, i.p., 15 min after Con A injection); and the Con A plus AM630 group was treated with Con A (20 mg/kg, i.v.) plus AM630 (2 mg/kg, i.p., 15 min after Con A injection). The serum and liver samples were harvested from the mice at 12 and 24 h after treatments.

Cell experiment

The Jurkat T-cell line was used as the T-cell model to examine the regulation of T-cell proliferation and apoptosis through CB2Rs. The CCK-8 assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions for detection of cytoactivity. The Jurkat cells were inoculated in 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells per well. The cells were treated with GW 0, 5, 10, 20, or 40 μg/mL. The cytoactive detection was conducted at 3, 6, 9, 12, 16, 20, or 24 h after GW treatment. The apoptosis of Jurkat cells was measured in the GW and GW plus AM630-treated groups using flow cytometry analysis. Jurkat cells were collected 24 h after the treatment with GW 10 μg/mL + AM630 1 μg/mL, GW 20 μg/mL + AM630 2 μg/mL, or GW 40 μg/mL + AM630 4 μg/mL. Cells were then stained with Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI). The percentage of Annexin V-FITC/PI-positive Jurkat T cells was determined by flow cytometry to evaluate the degree of apoptosis. For Western blot detection of Parp, the treatments of the Jurkat T cells used different concentrations of GW (0, 5, 10, or 20 μg/mL), different concentrations of AM630 (0, 5, 10, or 20 μg/mL), or GW (20 μg/mL) plus AM630 (2 μg/mL). The L02 liver cells were cocultured with Jurkat cells using a Transwell coculture system [20] to research the immune injury of the hepatocytes with 10% fetal bovine serum in 1640 medium for the coculture. Con A at 5 μg/mL was used to stimulate the Jurkat cells to release cytotoxic cytokines. GW 5 μg/mL or 10 μg/mL were used to reveal whether activation of CB2R could protect the L02 cells against cell toxicity from the Jurkat T cells. Furthermore, the AM630 was added to test whether the GW’s effects could be reversed, to confirm the critical roles played by the CB2Rs.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry

Liver tissues of mice were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections (thickness, 5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or antibodies for histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry (IHC). The stained sections were evaluated under a light microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot analysis

The total proteins from frozen liver tissue specimens or cells were isolated using RIPA buffer and quantitated using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo, USA). The protein extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After milk blockade of nonspecific binding sites, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with various antibodies against CB2R, Parp, BAX, BCL-2, and Caspase 3 followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Protein bands were visualized with an ECL reagent and exposed to X-ray films. Signals were assessed and normalized against the levels of actin or tubulin proteins.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the L02 cell and Jurkat cell samples using TRIzol reagent (Takara, China) and first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized. The cDNA samples were then incubated at 90 °C for 7 min to stop the reaction. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Takara, China) on the ABI7500 platform according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The primer sequences used were as follows: CB2R: sense, 5′-CTGCTTCTGGTTCCTGCTTC-3′ and antisense, 5′-GCGAACATCCTTGGTCCTTA-3′; the generation of specific PCR products was confirmed by melting curve analysis. The mRNA levels of CB2R were normalized against actin and relative expression was then calculated using the ΔΔCT method.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001, **** indicates P < 0.0001. ns indicates P > 0.05. T-tests were used to compare two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare more than two groups, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for pairwise comparisons.

Results

Effects of CB2Rs on ameliorating Con A-induced liver injury

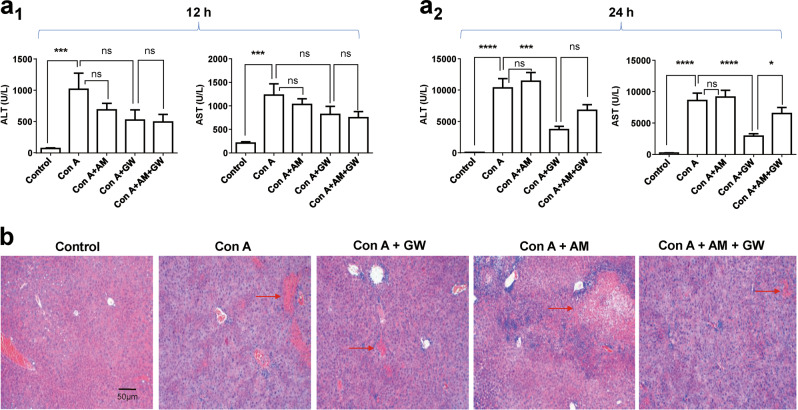

To determine the effects of CB2R on Con A-induced liver injury, mice were pretreated with Con A (20 mg/kg, i.v.) via the tail vein as a Con A model. These model mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20 mg/kg of GW (i.p., 30 min after Con A injection), 2 mg/kg of AM630 (i.p., 15 min after Con A injection), GW (i.p., 30 min after Con A injection) plus AM630 (i.p., 15 min after Con A injection) or vehicle. Serum ALT and AST activities were measured at 12 and 24 h after the above drug administrations. In the Con A-injected model group, 12 h after injection, serum ALT and AST were not significantly changed (Fig. 1a1). However, 24 h after injection of Con A, serum ALT and AST were significantly increased, which was eliminated by GW (Fig. 1a2). The protective effect of GW was reversed by AM630 (Fig. 1a2). To further confirm the effect of CB2R on liver injury, liver tissue sections with HE staining were evaluated. The Con A (after 24 h) induced massive hepatocyte necrosis and inflammatory cells infiltration, which were improved after addition of GW (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities were measured at 12 h (a1) and 24 h (a2) after concanavalin A (Con A) injection. Compared with the model group (Con A group), cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) agonists, GW405833 (GW) reduced ALT and AST, whereas CB2R antagonist, AM630 (AM) reversed GW’s effect, n = 15 for each group. b. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining ( × 100) demonstrated pathological alterations of liver section of five experimental groups. The Con A (after 24 h)-induced massive hepatocyte necrosis and inflammatory cells infiltration in the livers were improved after addition of GW (the red arrows indicate necrosis and inflammatory cells infiltration). In this and all following figures, data were presented as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. nsP > 0.05. T-test was used to compare two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare more than two groups, and Kruskal–Wallis test was used for pairwise comparison

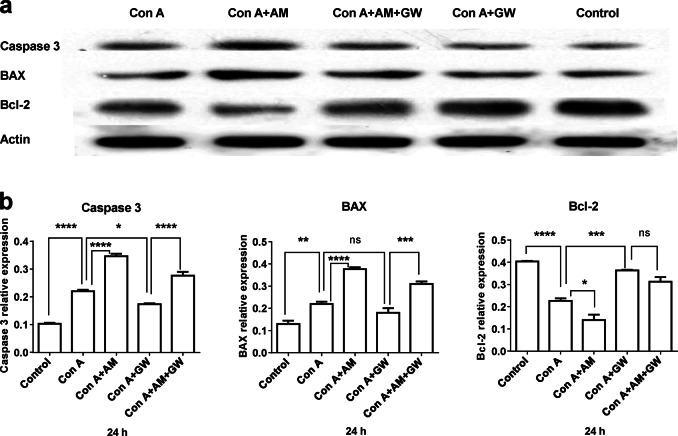

Effects of CB2R on ameliorating Con A-induced hepatic apoptosis of the liver tissue

The hepatocyte apoptosis of the liver tissue was detected by Western blotting. The activation of caspase 3 and BAX is crucial for the induction of apoptosis, and activated Bcl-2 represents an anti-apoptosis effect. Fig. 2a shows a sample of caspase 3, BAX, and Bcl-2 expression using Western blotting. Statistical analysis demonstrated that after 24-h treatment, both caspase 3 and BAX activity were increased in the Con A and Con A plus AM630 groups, whereas the Con A-induced increase was significantly suppressed in the Con A + GW group (Fig. 2b, left and middle panels). The anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-2 was decreased in both the Con A and Con A plus AM630 groups, and this reduction was reversed in the Con A + GW and Con A + GW plus AM630 groups (Fig. 2b, right panel).

Fig. 2.

GW405833 (GW) attenuated concanavalin A (Con A)-induced hepatic apoptosis in mice. Liver tissues were collected for histological examination. a Typical sample of the apoptosis-relative protein expression, caspase 3, BAX, and Bcl-2. b Statistical analysis, n = 3 for each group. Data were collected from all treated groups after 24-h treatment. Mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. nsP > 0.05

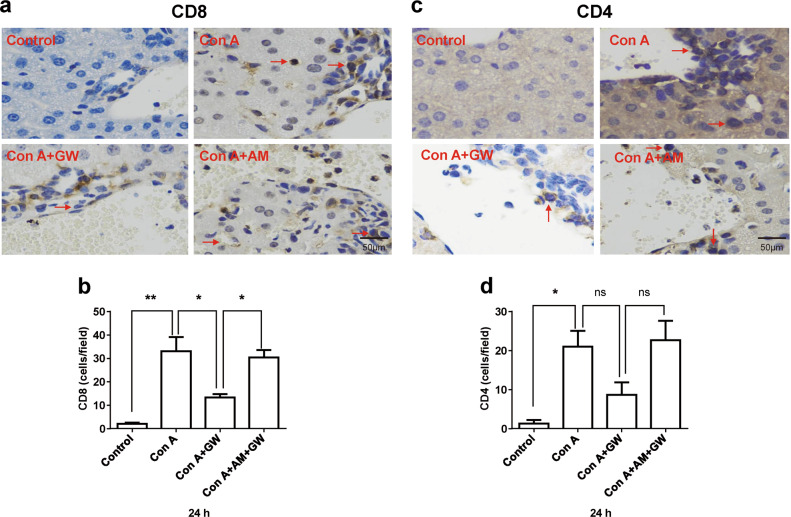

Lymphocytic infiltration was increased in the hepatic tissue

We compared lymphocytic infiltration (CD4 and CD8) between the control and treated groups (Con A, Con A + GW, and Con A + AM630). The results showed that lymphocytes (either CD8 or CD4) increased liver infiltration after Con A stimulation, which was prevented by treatment with GW, and the effect of GW was abolished by the CB2R antagonist, AM630 (Figs. 3a–d).

Fig. 3.

Lymphocytic infiltration (CD4 and CD8) was compared between control and treated groups. The lymphocytic infiltration detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) was compared between the normal liver and concanavalin A (Con A)-induced injured liver (400 × ), the red arrows indicate the infiltrative lymphocytes. The results showed that lymphocyte (either CD8 or CD4) increased liver infiltration by Con A stimulation, which was prevented by treatment with GW405833 (GW), and the effect of GW was abolished by cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) antagonist, AM630 (a–d). Statistical analysis, n = 3 for each group. Data were collected from all treated groups after 24-h treatment. Mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. nsP > 0.05

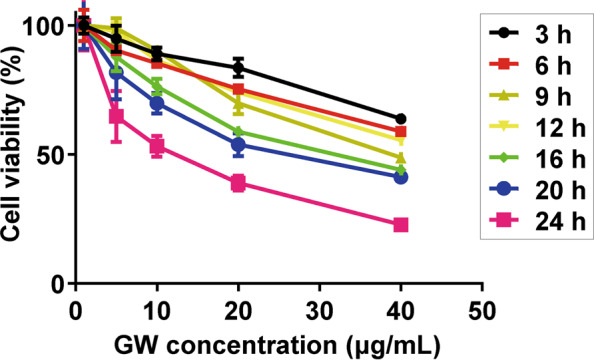

CB2R agonist GW inhibited the cytoactivity of Jurkat T lymphocytes

To detect the function of CB2R agonist GW on the cytoactive Jurkat T lymphocytes, the relative cytoactive rates of the Jurkat T lymphocytes measured at different time points (from 3 to 24 h) were tested by CCK-8. With increasing concentrations of GW and extended time of treatment, the cytoactive rate of the T lymphocytes was significantly reduced. The overall trend of cell viability declined under the dose-dependent and time-dependent effect of GW (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) agonist, GW405833 (GW) inhibited the cytoactivity of Jurkat T lymphocytes in both dose-dependent and time-dependent manners. With increased concentrations of GW and extending time of treatment, cytoactive rate of T lymphocytes was significantly reduced. The overall trend of cell viability declined under the dose-dependent and time-dependent effect of GW

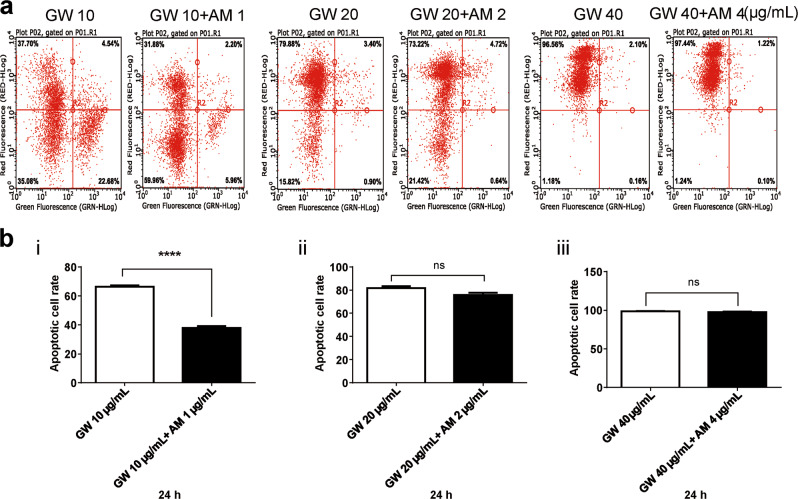

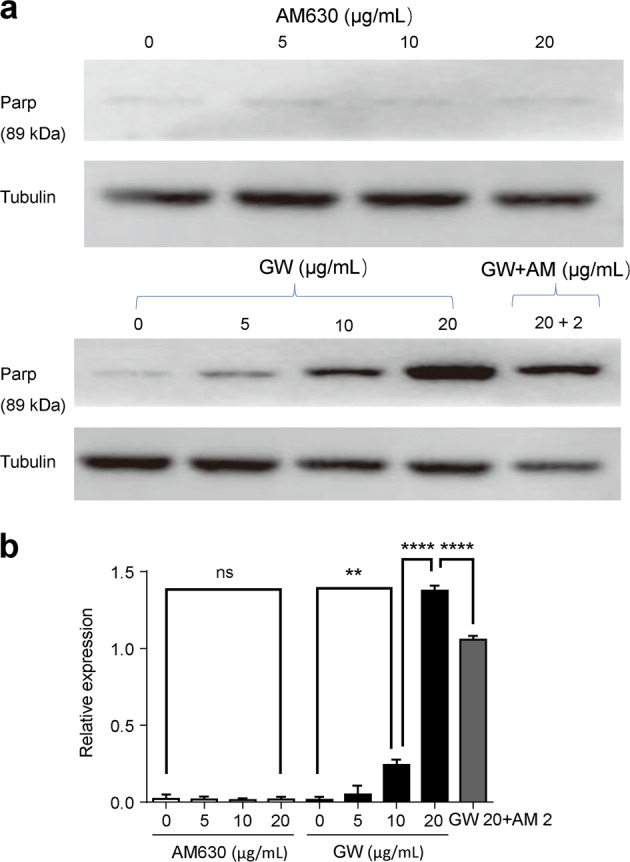

The apoptosis of T lymphocytes was regulated by GW via CB2Rs

To confirm whether GW affects the apoptosis of T lymphocytes, Jurkat T lymphocytes treated with GW and AM630 were stained by PI/Annexin V-FITC and detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 5a). The nucleus and cytomembrane of apoptotic cell would be marked by PI and Annexin V-FITC, respectively. The percentage of apoptotic Jurkat T lymphocytes were dose dependently increased with GW 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL. Statistical analysis showed that AM630 could prevent the apoptosis-promoting function of low concentrations of GW (Fig. 5bi). Consistently, the expression of apoptotic protein Parp (89 kDa) in Jurkat T lymphocytes was increased after CB2R stimulation with different concentrations of GW (Fig. 6a), and the AM630 reversed the GW-induced apoptosis of T lymphocytes (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 5.

The T lymphocytes were treated with GW405833 (GW) 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL, and GW 10 μg/mL + AM 1 μg/mL, GW 20 μg/mL + AM 2 μg/mL, GW 40 μg/mL + AM 4 μg/mL, respectively. The nucleus and cytomembrane of apoptotic cell were marked by propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V-FITC, respectively (a). The percentage of apoptotic cell after 24-h treatment was analyzed by flow cytometry, and n = 3 for each group (b). AM630 could prevent the apoptosis-promoting function of low concentrations of GW (bi). Mean ± SEM. ****P < 0.0001. nsP > 0.05

Fig. 6.

GW405833 (GW) promoted T lymphocytes apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. The cell apoptosis was determined by Parp (98 kDa). a Representative typical Parp (89 kDa) expression after treatment with either different concentrations of AM630 (top) or different concentrations of GW (bottom). b Statistical analysis of the effects of AM630 or GW or AM630 + GW on Parp (89 kDa) expression after 24 h treatment, n = 3 for each group. Cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) antagonist (AM630) reversed GW’s effects. Mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. nsP > 0.05

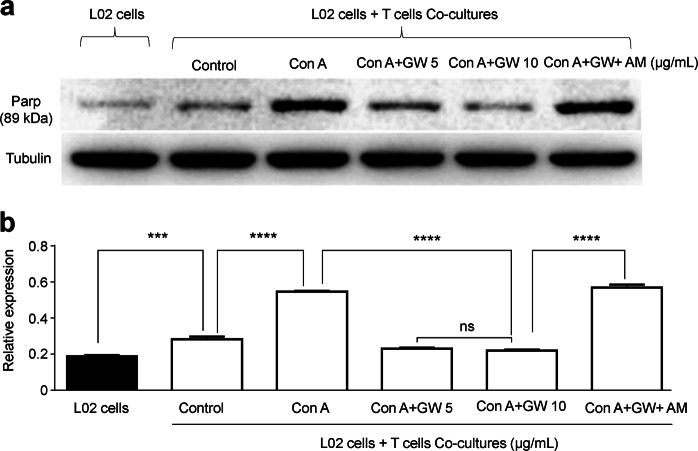

GW reduced the Con A-induced Jurkat T lymphocytes cytotoxic effect on hepatocytes by activating CB2Rs

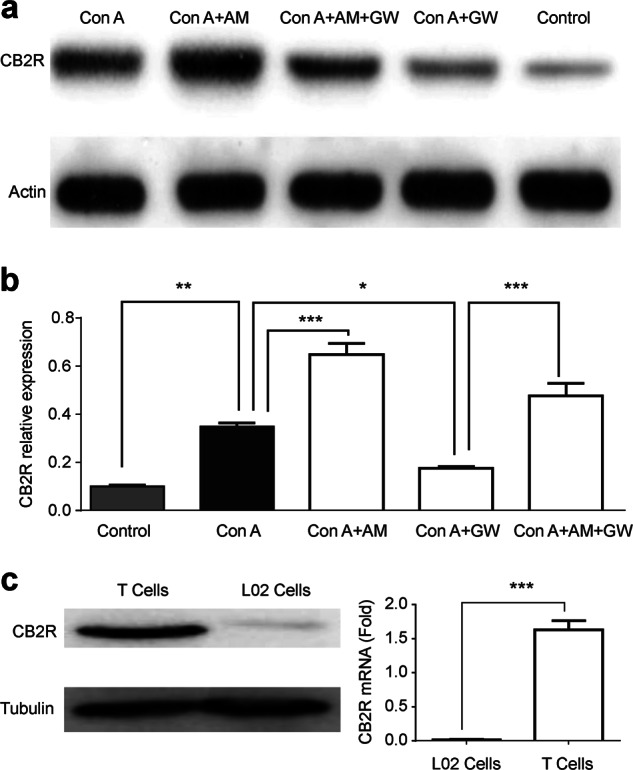

We use Transwells to coculture the Jurkat T lymphocytes and L02 liver cells for determining whether the protective effects of GW were mediated through the T cells or L02 cells. Con A stimulated Jurkat T lymphocytes, and in turn they had a cytotoxic effect on hepatocyte. We added Con A into the model of the coculture with a concentration gradient and applied GW or GW + AM630 intervention. The Con A-stimulated Jurkat T lymphocytes induced a cytotoxic effect on the L02 cells with increased Parp. However, activation of CB2Rs by GW could prevent cellular damage from Jurkat T lymphocytes in a GW concentration-dependent manner, and the AM630 (1 μg/mL) reversed the GW (10 μg/mL)-induced protective effects (Fig. 7), suggesting that GW protects liver L02 cells against Con A toxicity mediated by the Jurkat T lymphocytes. To confirm this idea, we examined CB2R mRNA and protein expression in liver tissue, Jurkat T lymphocytes and L02 liver cells, and showed that liver CB2R expression was increased by Con A and Con A plus AM630, whereas addition of GW (Con A + GW) prevented Con A-induced increases in CB2R expression, and AM630 reduced GW’s effect (Fig. 8a, b). Furthermore, we found that CB2R expression was found at a high level on Jurkat T lymphocytes, but there was little expression on L02 liver cells as shown by western blotting (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 7.

Effects of T-cell toxicity on L02 liver cells. The L02 liver cells and the T lymphocytes were cocultured to evaluate the toxicity of T lymphocytes to liver L02 cells. a T lymphocytes was activated by concanavalin A (Con A) that made the cytotoxic effect, and cell apoptosis of L02 liver cells was measured by Parp (89 kDa). b Statistical analysis showed that GW405833 (GW) inhibited T lymphocytes and protected L02 liver cells against T-cell toxicity. The cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) antagonist (AM630) would counteract the protective effect. n = 3 for each group. Mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. nsP > 0.05

Fig. 8.

Cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) expression in liver tissue, T cells and L02 cells. Mice were treated with concanavalin A (Con A) for 24 h to induce liver injury. a CB2R expression was detected by Western blot (anti-mouse-CB2R antibody) in five experimental groups. b Bar graph shows CB2R expression in five groups, n = 3 for each group. c CB2R expressions in T cells and L02 cells were detected by Western blot (anti-human-CB2R antibody) and real-time quantitative PCR. n = 3 for each group. Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Discussion

Acute liver injury may develop into acute liver failure if it is not properly treated in time. There is no effective treatment for acute liver failure at present. Immune inflammation plays an important role in acute liver injury [21–23]. In the course of acute liver injury, a large number of lymphoid T cells are found [24]. Although CB2R is mainly expressed in the immune cells, it has been reported to protect against liver damage in various diseases, including alcoholic liver injury, that are related to immune cells [25, 26]. Therefore, screening special agonists or drugs targeting CB2Rs for immune function regulation might be a new feasible approach to the treatment of acute liver injury.

GW, as a selective CB2R agonist, has been reported to protect against acute pancreatitis by activating CB2R [27, 28]. However, whether GW protects against acute liver injury remains unknown. Our research showed that GW effectively protected Con A-induced acute liver injury in mice, as demonstrated by a decreased serum aminotransferase level, improved liver histopathology, and decreased hepatocyte apoptosis. Additionally, the protective effect of GW could be abolished by the CB2R-specific antagonist AM630 in both animal and cellular experiments, indicating that the protective effect of GW on acute liver injury is achieved through activating CB2R instead of other off-target effects. On the other hand, considering the CB2R expression in hepatocytes is almost undetectable, an increase in CB2R expression in acute damaged liver tissue could be attributed to the increased number of infiltrated lymphocytes. Interestingly, we found that application of CB2R antagonist, AM630, in conjunction with Con A, increased Con A-induced toxicity, suggesting that endogenous CB2Rs expressed in T cells participate as agonists against Con A-induced acute injury of the liver. These results collectively demonstrated that GW protects against liver damage by regulating immune cells through activating CB2R.

To explore why activation of CB2R in T cells could protect hepatocytes against acute injury to the liver, a coculture cell model was employed as previously described [29, 30]. Addition of GW inhibited the Con A-induced apoptosis of L02, and AM630 reversed this effect. As there is almost no expression of CB2R in L02, we speculated that the administration of GW preferably activated CB2R in T cells. The activated CB2R would consequently reduce the amount of cytokines released by promoting T-cell apoptosis, which in turn protects rescued hepatocytes from damage.

In summary, this study provides evidence that GW inhibits T-cell proliferation and promotes T-cell apoptosis by activating CB2Rs, thereby protecting hepatocytes against damage induced by an immune response induced by the original acute liver injury. Although different factors might induce acute liver injury via diverse mechanisms, the CB2R agonist GW is a promising candidate for treatment of immune-relevant acute liver injury.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81700561), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (2016JJ3164, 2017JJ3496, 2017JJ2385), and the Project of Science and Technology Agency of Hunan Province, China (2014SK4066).

Author contributions

ZBH and YXZ performed animal experiments and wrote the manuscript; NL designed the research; SLC performed part of the cell experiments; YH designed the research; JW performed part of the cell experiments; XWH and YW wrote part of the manuscript; XGF designed the experiments and edited the manuscript; JW designed the experiments, analyzed the data, revised all figures, and revised the manuscript.The authors declare no competing fnancial interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Ze-bing Huang, Yi-xiang Zheng.

Contributor Information

Jie Wu, Email: jiewubni@gmail.com.

Xue-gong Fan, Email: xgfan@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Chen J, Zhao SS, Liu XX, Huang ZB, Huang Y. Comparison of the efficacy of tenofovir versus tenofovir plus entecavir in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B in patients with poor efficacy of entecavir: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2017;39:1870–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vellozzi C, Averhoff F. An opportunity for further control of hepatitis B in China? Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:10–11. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang ZB, Zhao SS, Huang Y, Dai XH, Zhou RR, Yi PP, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of Lamivudine plus adefovir versus entecavir in the treatment of Lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2013;35:1997–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernal W, Jalan R, Quaglia A, Simpson K, Wendon J, Burroughs A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Lancet. 2015;386:1576–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammerich L, Bangen JM, Govaere O, Zimmermann HW, Gassler N, Huss S, et al. Chemokine receptor CCR6-dependent accumulation of gammadelta T cells in injured liver restricts hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology. 2014;59:630–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.26697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crispe IN. Immune tolerance in liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;60:2109–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.27254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamoto Y, Kaneko S. Mechanisms of viral hepatitis induced liver injury. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:537–44. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horras CJ, Lamb CL, Mitchell KA. Regulation of hepatocyte fate by interferon-gamma. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim HS, Jin SE, Kim OS, Shin HK, Jeong S. J. Alantolactone from Saussurea lappa exerts antiinflammatory effects by inhibiting chemokine production and STAT1 phosphorylation in TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma-induced in HaCaT cells. Phytother Res. 2015;29:1088–96. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Rydzewski R, et al. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology. 2004;40:185–94. doi: 10.1002/hep.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Zhang W, Ge CH, Yin RH, Xiao Y, Zhan YQ, et al. Toll-like receptor 5 signaling restrains T-cell/natural killer T-cell activation and protects against concanavalin A-induced hepatic injury. Hepatology. 2017;65:2059–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.29140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabral GA, Ferreira GA, Jamerson MJ. Endocannabinoids and the immune system in health and disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;231:185–211. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20825-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson RH, Meissler JJ, Fan X, Yu D, Adler MW, Eisenstein TK. ACB2-selective cannabinoid suppresses T-cell activities and increases Tregs and IL-10. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015;10:318–32. doi: 10.1007/s11481-015-9611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson RH, Meissler JJ, Breslow-Deckman JM, Gaughan J, Adler MW, Eisenstein T. K. Cannabinoids inhibit T-cells via cannabinoid receptor 2 in an in vitro assay for graft rejection, the mixed lymphocyte reaction. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:1239–50. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9485-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong Y, Wang W, Zhang C, Wu Y, Liu Y, Zhou X. Cannabinoid WIN55,2122 mesylate inhibits ADAMTS4 activity in human osteoarthritic articular chondrocytes by inhibiting expression of syndecan1. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:4569–76. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valenzano KJ, Tafesse L, Lee G, Harrison JE, Boulet JM, Gottshall SL, et al. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characterization of the cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist, GW405833, utilizing rodent models of acute and chronic pain, anxiety, ataxia and catalepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:658–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gui H, Sun Y, Luo ZM, Su DF, Dai SM, Liu X. Cannabinoid receptor 2 protects against acute experimental sepsis in mice. Mediat Inflamm. 2013;2013:741303. doi: 10.1155/2013/741303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato J, Okamoto T, Motoyama H, Uchiyama R, Kirchhofer D, Van Rooijen N, et al. Interferon-gamma-mediated tissue factor expression contributes to T-cell-mediated hepatitis through induction of hypercoagulation in mice. Hepatology. 2013;57:362–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.26027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegde VL, Hegde S, Cravatt BF, Hofseth LJ, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Attenuation of experimental autoimmune hepatitis by exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids: involvement of regulatory T cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:20–33. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.047035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Yang D, Shi S, Lin L, Xiao M, Yuan Z, et al. Overexpression of vasostatin-1 protects hypoxia/reoxygenation injuries in cardiomyocytes-endothelial cells transwell co-culture system. Cell Biol Int. 2014;38:26–31. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamoto N, Amiya T, Aoki R, Taniki N, Koda Y, Miyamoto K, et al. Commensal lactobacillus controls immune tolerance during acute liver injury in mice. Cell Rep. 2017;21:1215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansi Y, Ghaffar SA, Sayed S, El-Karaksy H. The effect of nutritional status on outcome of hospitalization in paediatric liver disease patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:SC01–SC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21606.8956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou RR, Liu HB, Peng JP, Huang Y, Li N, Xiao MF, et al. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients and mice with ConA-induced acute liver injury. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;93:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L, Zhao Y, Qin Y, Xu Q. Anovel model of acute liver injury in mice induced by T cell-mediated immune response to lactosylated bovine serum albumin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:125–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denaes T, Lodder J, Chobert MN, Ruiz I, Pawlotsky JM, Lotersztajn S, et al. The cannabinoid receptor 2 protects against alcoholic liver disease via a macrophage autophagy-dependent pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28806. doi: 10.1038/srep28806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louvet A, Teixeira-Clerc F, Chobert MN, Deveaux V, Pavoine C, Zimmer A, et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors protect against alcoholic liver disease by regulating Kupffer cell polarization in mice. Hepatology. 2011;54:1217–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.24524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Z, Wang H, Wang J, Zhao M, Sun N, Sun F, et al. Cannabinoid receptor subtype 2 (CB2R) agonist, GW405833 reduces agonist-induced Ca2+oscillations in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29757. doi: 10.1038/srep29757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michler T, Storr M, Kramer J, Ochs S, Malo A, Reu S, et al. Activation of cannabinoid receptor 2 reduces inflammation in acute experimental pancreatitis via intra-acinar activation of p38 and MK2-dependent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G181–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00133.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danoy M, Shinohara M, Rizki-Safitri A, Collard D, Senez V, Sakai Y. Alteration of pancreatic carcinoma and promyeloblastic cell adhesion in liver microvasculature by co-culture of hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells and endothelial cells in a physiologically-relevant model. Integr Biol (Camb) 2017;9:350–61. doi: 10.1039/c6ib00237d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melton AC, Melrose J, Alajoki L, Privat S, Cho H, Brown N, et al. Regulation of IL-17A production is distinct from IL-17F in a primary human cell co-culture model of T cell-mediated B cell activation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]