Abstract

Optimal treatment of breast cancer brain metastases (BCBM) is often hampered by limitations in diagnostic abilities. Developing innovative tools for BCBM diagnosis is vital for early detection and effective treatment. This study explores the advances in trial for the diagnosis of BCBM, with review of literature. On May 8, 2019, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov for interventional and diagnostic clinical trials involving BCBM, without limiting for date or location. Information on trial characteristics, experimental interventions, results and publications were collected and analyzed. In addition, a systematic review of the literature was conducted to explore published studies related to BCBM diagnosis. Only nine diagnostic trials explored BCBM. Of these, one trial was withdrawn due to low accrual numbers. Three trials were completed; however, none had published results. Modalities in trial for BCBM diagnosis entailed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), PET-CT, nanobodies and circulating tumor cells (CTCs), along with a collection of novel tracers and imaging biomarkers. MRI continues to be the diagnostic modality of choice, whereas CT is best suited for acute settings. Advances in PET and PET-CT allow the collection of metabolic and functional information related to BCBM. CTC characterization can help reflect on the molecular foundations of BCBM, whereas cell-free DNA offers new genetic material for further exploration in trials. The integration of machine learning in BCBM diagnosis seems inevitable as we continue to aim for rapid and accurate detection and better patient outcomes.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Computed Tomography (CT), Positron emission tomography (PET), Nanobody, Circulating tumor cells, cell-free DNA (cfDNA), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Systematic Review, Clinical trials

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, regardless of race or ethnicity.1 In 2018, an estimated 266,120 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in women in the United States alone.2 Autopsy studies reveal that close to 30% of these patients will eventually develop neurological symptoms due to brain metastases at the later stages of the disease.3 Brain metastases are usually characterized by multiple lesions spread variably at the gray-white junction and/or smooth margins of the brain.4 They can also present as small tumor foci with or without abundant vasogenic edema,5 depending on tumor size. Brain metastases can lead to significant morbidity and mortality; however, early detection of breast cancer can have significant impact on survival and quality of life.6, 7

Treatment options for breast cancer brain metastases (BCBM) are limited to surgery, whole-brain radiotherapy, stereotactic radiosurgery and systemic drug therapy,8 with limited efficacy. Targeted therapies with monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, have shown some promise for oncologic management of patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive BCBM.9 Furthermore, targeting estrogen receptor (ER)-positive BCBM with endocrine agents, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, and mTOR inhibitors have considerably affected the decision-making process in the treatment of patients with BCBM.10 Although hardly curative, early diagnosis and treatment of BCBM have prolonged remission.11 Therefore, it is crucial to understand the current concepts of assessment in these patients because accurate and timely diagnosis is essential for effective treatment.

Diagnosis of BCBM relies heavily on clinical information and neuro-imaging modalities, and can be confirmed with pathological examination. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the neuro-imaging modality of choice in BCBM settings.12 Computed tomography (CT) scan can be a helpful diagnostic tool in acute settings to rule out hemorrhage and effusions; however, it lacks the resolution, coverage and attention-to-detail that are offered with MRI. Still, CT is widely accessible and its diagnostic results can be obtained swiftly. Histology, in addition to clinical and radiological inputs, helps differentiate BCBM from primary brain tumors. Immunohistochemistry markers, like GATA3 binding protein, mammaglobin, GCDFP-15 and ER can also be helpful in confirming the breast tissue of origin.13 Nevertheless, pathological evaluations are often limited by poor differentiation and/or unavailability of BCBM tissue to reach accurate diagnoses.

A number of clinical trials are currently running with the aim of optimizing BCBM diagnoses. This work explores the advances in these trials to achieve a clearer understanding of the developments in diagnostic technology, and aim for better treatment and management of patients with BCBM.

METHODS

Study Design

ClinicalTrials.gov is a large clinical trial database that registers a high number of trial entries, weekly. Its submission process compels providing thorough information on trial profile and history, and description of registered protocols. The ability to conduct analysis and extrapolate conclusions on clinical trials’ data from the registry has been previously elaborated on.14–16

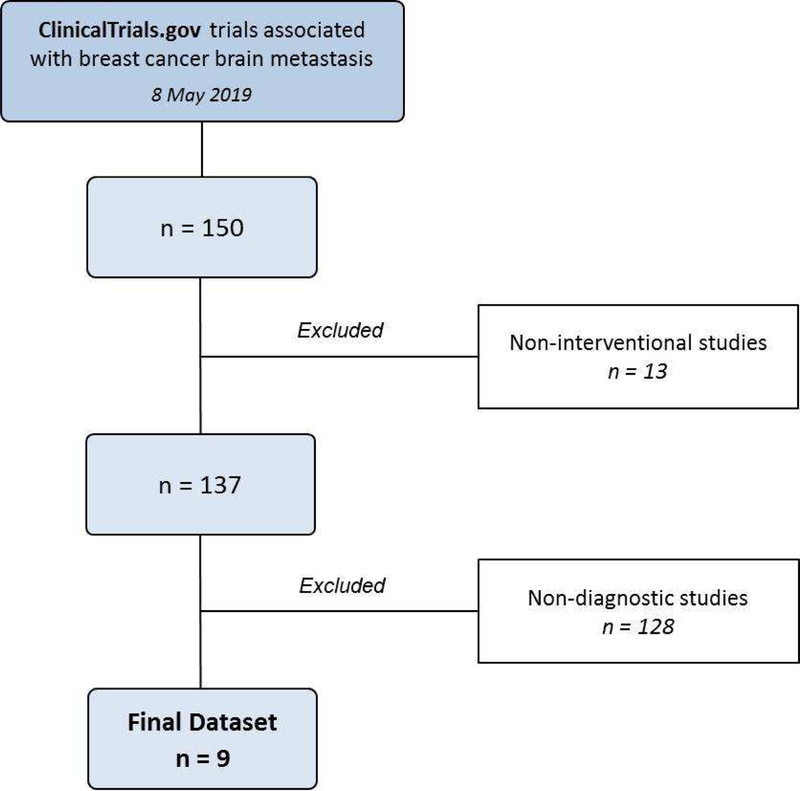

On May 8, 2019, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov for all trials involving BCBM, without limiting for date or location. Following an elimination schema similar to Fares et al.,17 13 trials were removed as they were non-interventional studies and/or clinical trials that do not list BCBM in the title or as a condition treated. Another 128 trials were excluded as they were non-diagnostic (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical trial selection process

Data Collection

Information was acquired from the final data set on trial characteristics, including: phase, status, start and end dates, outcome measures, selection criteria, sample size, study design, experimental interventions, location, results and publication. Trial history of changes was obtained using the ClinicalTrials.gov archives site. Trial publications were obtained using the ClinicalTrials.gov registry number (NCTID). NCTID identifiers were searched for on the Pubmed/Medline and Embase/Scopus records to locate publications. If the trial was published, the NCTID identifier was included as part of the original paper and the paper will appear in the search result.

Literature Review

A review of PubMed/Medline and Embase/Scopus databases was conducted to identify published studies on current diagnostic modalities in BCBM. Combinations of search terms used included “breast cancer,” “breast neoplasms,” “brain metastases,” “brain tumors,” “brain malignancy,” “diagnostic modalities,” “magnetic resonance imaging,” “MRI,” “computed tomography,” “CT,” “positron emission tomography,” “PET,” “circulating tumor cells,” “nanobodies,” “clinical trials,” “artificial intelligence,” “AI” and “machine learning.” Studies available in English were included. All identified abstracts from these searches were analyzed, and those that reviewed or examined diagnostic modalities associated with BCBM were included.

RESULTS

Only 9 diagnostic trials exclusively explored BCBM (Table 1). Of which, 1 trial was withdrawn due to low accrual numbers. The rest continue to progress. Three trials are yet to reach their primary completion dates. Four trials were located in the United States, 3 in Belgium, 1 in Canada and 1 in Brazil. Of all trials, 3 were completed. None of the trials have provided results or led to publications.

Table 1:

Diagnostic clinical trials in breast cancer brain metastases as found in ClinicalTrials.gov as of May 8, 2019 (n = 9)

| NCTID | Trial | Status | Condition | Interventions | Phase | Outcome Measures | Study Design | Preplanned Population | Study Start | Primary Completion | Locations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the Early Detection of CNS Metastases in Women With Stage IV Breast Cancer | Withdrawn | Breast cancer brain metastases | Trastuzumab; chemotherapy; MRI | NA | Survival without neurological symptoms | Randomized | 96 | September 2006 | - | Belgium | |

| F18 EF5 PET/CT Imaging in Patients With Brain Metastases From Breast Cancer | Completed | Breast cancer brain metastases | PET/CT imaging | NA | Number of adverse events | - | 10 | March 2011 | August 2016 | United States | |

| MM-398 (Nanoliposomal Irinotecan, Nal-IRI) to Determine Tumor Drug Levels and to Evaluate the Feasibility of Ferumoxytol Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Measure Tumor Associated Macrophages and to Predict Patient Response to Treatment | Completed | Breast cancer brain metastases | Ferumoxytol MRI and MM398 | I | Tumor levels of irinotecan and SN-38 | Non-Randomized; single group assignment; open Label | 45 | November 2012 | October 2018 | United States | |

| 18F-FLT-PET Imaging of the Brain in Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer to the Brain Treated With Whole Brain Radiation Therapy With or Without Sorafenib: Comparison With MR Imaging of the Brain | Recruiting | Breast cancer brain metastases | 18F-FLT-PET Imaging | NA | Radiographic response | Nonrandomized; parallel assignment; open Label | 20 | June 2012 | June 2019 | United States | |

| Imaging the Patterns of Breast Cancer Early Metastases (BCMetPats) | Active, not recruiting | Metastatic breast cancer | PET, MRI and CT scans | NA | Number, size and location of metastases | Single group assignment; open label | 13 | April 2016 | January 2018 | United States | |

| Correlation Between Circulating Tumor Cells and Brain Disease Control After Focal Radiotherapy for Metastases of Breast Cancer | Completed | Breast cancer brain metastases | Circulating tumor cells evaluation | NA | Brain progression-free survival; overall survival | Single group assignment; open label | 40 | November 2016 | October 2018 | Brazil | |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Whole Body, Including Diffusion, in the Medical Evaluation of Breast Cancers at High Risk for Metastasis and the Follow-up of Metastatic Cancers | Recruiting | Hormone-sensitive metastatic breast cancer | Whole body MRI | NA | Apparent diffusion coefficient; number and location of cancer lesions | Single group assignment; open label | 50 | December 2016 | September 2018 | Belgium | |

| Evaluation of 68-GaNOTA-Anti-HER2 VHH1 Uptake in Brain Metastasis of Breast Carcinoma Patients | Recruiting | HER2-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer | 68GaNOTA-Anti-HER2 VHH1 | II | Tumor targeting potential in brain metastasis | Single group assignment | 30 | February 2017 | September 2021 | Belgium | |

| MRI Screening Versus SYMptomdirected Surveillance for Brain Metastases Among Patients With Triple Negative or HER2+ MBC (SYMPToM) | Recruiting | Breast cancer brain metastases | MRI | NA | Screening for brain metastases | Randomized | 50 | November 2018 | June 2021 | Canada |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Since the 1980s, contrast-enhanced MRI has become the preferred imaging modality for the diagnosis of BCBM. It is more sensitive than either non-enhanced MRI or CT scanning in detecting lesions in patients suspected of having brain metastases.18 It is also superior in differentiating metastases from other central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Often, when neurological symptoms are present, the metastases are too large and/or numerous to be treated with a curative intent; therefore, diagnosis of small and isolated BCBM will allow neurosurgical resection or locally ablative radiation therapy. Early detection of CNS metastases in women with invasive breast cancer using gadolinium-enhanced MRI is in trial (, and ). This will allow the documentation of patterns of early metastatic spread of breast cancer, and provide a basis to determine how to optimize future surveillance imaging protocols with respect to the time to progression, rate of tumor growth and affected organs.

There are multiple ways through which MRI can enhance the visibility of BCBM. Increasing the MRI field strength and the levels of gadolinium-based contrast agents can increase sensitivity and lead to detection of small BCBM (<5mm).19 Nevertheless, the nephrotoxicity resulting from increasing contrast remains a concern that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) often counsels against.20 Yet, the availability of contrast agents that exhibit different biophysical properties allows for selecting the most suitable contrast agent while taking into account the dosing, field strength and safety profile. Furthermore, increasing the time between contrast injection and acquisition of images can enhance the detection of BCBM. Kushnirsky et al.21 instated a time delay of 15 minutes after contrast injection and found out that at least one additional brain lesion was being detected in 43% of patients. Nonetheless, time delay might be problematic for patients as it increases costs and time spent in a potentially uncomfortable setting.12 In addition, practitioners and researchers might find it inconvenient because it increases time of image acquisition and data collection. Moreover, the MRI sequence chosen and the relative slice thickness can also affect the detection of BCBM. Volumetric contrast-enhanced acquisition with a slice thickness of 1–2 mm (without a gap) yields detailed and finer images that can be reconstructed in a plane.22 This enhances the detection of smaller BCBM. Besides, the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, has demonstrated remarkable progress in image-recognition tasks.23 Algorithms, in addition to the interpretation of radiologists and practitioners, lead to greater sensitivity and better accuracy of BCBM diagnosis.

Using a variety of techniques, MRI can provide a breadth of physiological data on BCBM, beyond just brain metastasis anatomy. MR perfusion imaging can generate data like cerebral blood volume (blood within a defined volume of tissue), cerebral blood flow (blood that passes through the tissue per unit of time) and Ktrans, a transfer contrast coefficient that is related to the leakiness of blood vessels.24 MR diffusion techniques can show the metastatic tumor’s vasogenic edema, which appears bright on diffusion-weighted images. It can also display the capacious growth pattern of BCBM that can displace surrounding tissue as can be revealed by diffusion-tensor images (DTI). Proton spectroscopy can provide clues on tumor histology and grade. It can also help in locating the best site for biopsy. Altogether, these techniques enhance the accuracy of BCBM diagnosis and subsequently lead to a better estimation of the therapeutic response.

In 2018, the FDA approved ferumoxytol, an intravenously injected ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxide, as a supplemental new treatment for individuals with iron-deficiency anemia who cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to oral iron.25 Due to its MRI contrast characteristics,26 ferumoxytol has also been investigated as an imaging agent in metastatic brain tumors, including BCBM. After injection, ferumoxytol is taken by tumor-associated macrophages to showcase tumor volume and size. Hamilton et al.27 found no difference between T1-weighted MRI when comparing a gadolinium-based contrast agent to ferumoxytol in untreated brain tumors. As ferumoxytol does not contain gadolinium, nephrotoxicity can be avoided. Moreover, ferumoxytol was tested as a predictive biomarker of tumor deposition for MM-398 (Nanoliposomal Irinotecan, nal-IRI). Nal-IRI is a nanoliposomal agent that is believed to have an anti-tumor activity in metastatic breast cancer. It is designed to exploit areas of BBB breakdown for enhanced drug delivery to tumors. Tumor deposition of nal-IRI and subsequent conversion to SN-38, a hyperactive antineoplastic nal-IRI metabolite, in both neoplastic cells and tumor-associated macrophages may instigate clinical benefit and anti-tumor response.28 The pattern of distribution of ferumoxytol in tumor-associated macrophages is similar to that of nal-IRI.29 As such, BCBM permeability to ferumoxytol may be a predictive biomarker for nal-IRI deposition and tumor response. A phase 1 study is being conducted in patients with BCBM treated with nal-IRI to determine and evaluate the feasibility of ferumoxytol-MRI in measuring tumor-associated macrophages and predicting patient response to treatment ().

Computed Tomography Imaging

The rise of MRI ousted CT as the preferred imaging of choice for the diagnosis and follow up of patients with BCBM. As such, CT imaging is not currently in trial for BCBM. Nevertheless, CT scans, despite lower sensitivity, continue to be prioritized for screening patients with acute neurological symptoms and/or in emergency settings.12 Furthermore, presenting patients with implanted devices that are contraindicated to undergo MRI might have to settle for a CT scan instead.

Positron Emission Tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) provides metabolic information on BCBM to complement the anatomical and physiological data collected by MRI or CT. PET measures glucose consumption in tumor cells through a positron emitter 18-fluorine (18F) incorporated in a common tracer, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG).30 This tracer is a glucose analog that has a long half-life and is taken by the active BCBM cell. Therefore, PET imaging will reveal the extent of glucose metabolism in BCBM cells. Nevertheless, the brain consumes up to 20% of the energy produced by the body, with glucose being the basic source of energy. FDG tracers can be challenged by background signaling coming from high metabolic activity and glucose consumption in the brain.31 In addition, FDG has low specificity in the presence of treatment-induced inflammation around the tumor site,32 as inflammatory cells have the ability to uptake FDG. This results in overestimating tumor cell quantity, which confines the ability of FDG-PET to detect smaller lesions of BCBM.

Non-invasive molecular imaging biomarkers of cellular proliferation have the potential to characterize brain tumors and predict their responses to personalized therapeutic regimens in BCBM. A new clinical approach to assess tumor proliferation uses the PET marker 3’-deoxy-3’[18F]-fluorothymidine (FLT). One trial () is currently recruiting patients to prove that FLT-PET is better than MRI and will be more informative about the brain metastases after whole brain radiotherapy. Unlike FDG, FLT’s ability of evaluating whole tumor heterogeneity instead of glucose metabolism allows for less false positive results.33

Positron Emission Tomography – Computed Tomography

Image fusion with PET/CT views correlates the information from the two different modalities and interprets them on one image. Functional measures captured by PET, like blood flow, oxygen use and glucose metabolism, are added to the anatomical information provided by CT. The combined PET/CT scans provide images that pinpoint the anatomic location of abnormal metabolic activity within the body. The combined scans have been shown to provide more accurate diagnoses than the two scans performed separately.34

Angiogenesis, formation of new blood vessels, is vital for the growth of BCBM. Nevertheless, angiogenesis is often unable to keep up with the rapidly-growing metastases, which hampers blood supply to the tumor. The lack of oxygen and nutrient delivery to the tumor leads to a state of tumor hypoxia. Imaging of hypoxia has been the subject of intense research in neuro-oncology since hypoxic brain tumors tend to confer resistance to radiotherapy.35 Furthermore, the remaining hypoxic tissue may contribute to the failure of treatment post-radiotherapy.36 Counter-resistance can be achieved by increasing the doses of radiotherapy through stereotactic radiosurgery. This has been shown to improve survival in patients after receiving whole brain radiotherapy.37

Determining the amount of hypoxic tissue remaining after radiotherapy is vital to identify patients that can benefit from dose escalation. A clinical trial was designed to detect residual tumor hypoxia in patients with BCBM who were receiving whole-brain radiation therapy by using a non-invasive imaging biomarker 18F-EF5 (EF5) and PET/CT imaging (). Several hypoxia tracers have been tested; however, the most promising has been EF5.38 Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that EF5 is associated with aggressive tumors like malignant glioma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and sarcomas.39, 40

The overexpression of the HER2 protein is associated with increased BCBM.41 Hence, determining HER2 status is essential for identifying patients who would benefit from anti-HER2 treatment. Common diagnostic modalities that reveal HER2 status include a biopsy of tumor sample followed by tests such as immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization staining.41 Unfortunately, these tests are operator-dependent, prone to sampling error in biopsy and not easily repeatable. PET/CT molecular imaging provides a platform whereby these inadequacies can be addressed, and a more accurate and quantitative assessment of HER2 expression in patients with breast cancer is possible.

Nanobodies are the smallest (12–15 kDa) fully functional and intact antigen-binding antibody fragments.42 In addition to their adequately small size, they demonstrate high stability, rapid targeting and fast blood clearance, which make them ideal candidates for molecular imaging probing.42 In preclinical settings, HER2 imaging, using nanobodies with PET-labeled analogs, was performed 1 h after injection.43 Results showed significant differences in HER2 expression between tumor and muscle, and tumor and blood. Validation studies revealed high-specific-contrast imaging of HER2-positive tumors with no observed toxicity.44 Subsequently, a phase 2 clinical trial was designed to investigate the uptake of the radiopharmaceutical anti-HER2 nanobody, 68-GaNOTA-Anti-HER2 VHH1, in BCBM using PET/CT imaging (). Ultimately, uptake in patients with HER2-positive BCBM will be compared to that in patients with HER2-negative BCBM.

Circulating Tumor Cells

Circulating tumor cells (CTC) in patients with breast cancer originate from the primary breast tumor. They can continuously flow in the blood or can cluster together to colonize distant sites, like the brain parenchyma.45 No matter the destination, CTCs continue to preserve the information of their primary origin. This information is vital for cancer diagnosis and/or treatment. For this reason, a clinical trial was designed to assess the number of CTCs before and after radiotherapy (). Potential invasion markers in these CTCs would be evaluated and correlated with incidence of BCBM. A positive association will offer the ability to target BCBM in real time.

CTCs were first described in 1869.46 In the past decade, studies have emerged to show that CTCs can act as markers of disease progression and metastases in patients with cancer.47, 48 Elevated levels of CTCs correlate with aggressive disease and increase in metastases. Although it is still not clearly established that CTCs are indeed metastatic cells, CTCs were capable of initiating metastases in xenograft models.49 Therefore, CTCs can be important indicators and contributors in tumor staging and patient stratification in BCBM.

CTCs can be obtained through minimally invasive blood collection. It is estimated that patients with cancer may have only 5–50 CTCs per teaspoon of blood.50 Fortunately, technological advancements in the past decades have allowed the isolation of CTCs from the white blood cell fraction.51 Assessing numbers of CTCs accompanied with molecular characterization possesses the potential to guide therapy and predict disease progression and survival.

DISCUSSION

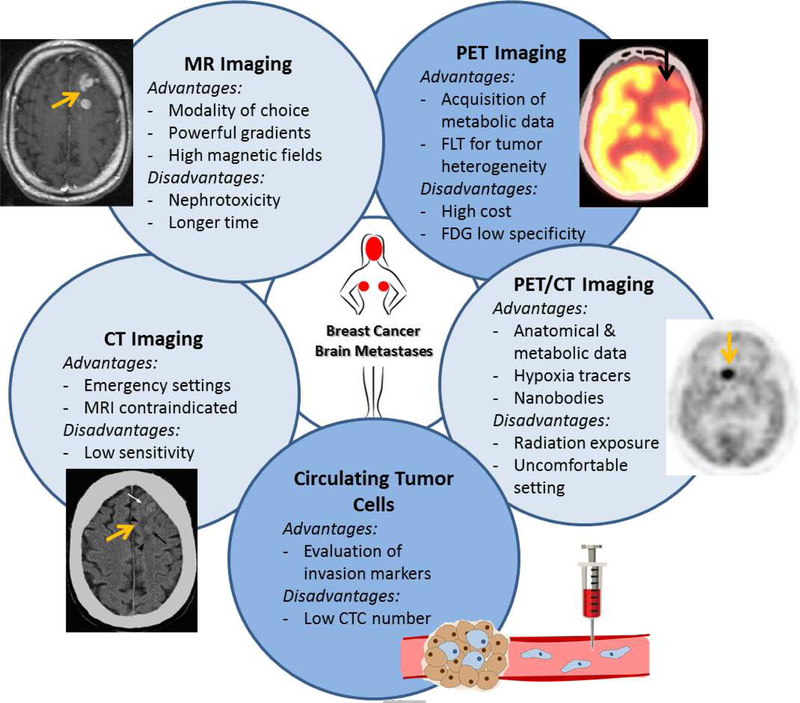

The poor survival associated with BCBM warrants the development of new and innovative diagnostic tools that can detect metastatic potential of breast cancer cells as early as possible (Figure 2). This is further emphasized by the fact that the outcome of surgical, radiation and/or targeted therapy is largely dependent on early diagnosis of BCBM. Therefore, multicenter collaborations and extensive participation in clinical trials is essential so that BCBM diagnostic trials succeed in their mission to remove the ‘end-stage disease’ label associated with BCBM.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic modalities of breast cancer brain metastases that are in trial, as of May 8, 2019

MRI has evolved into the premier diagnostic modality for BCBM. Higher field magnets offer the ability to achieve spatial resolutions that can visualize in detail the exquisite brain anatomy.52 In addition, the availability of intraoperative MRI has influenced neurosurgical therapy of BCBM. Intraoperative image updates can be obtained in short-time and the resection progress can be readily monitored.52 Furthermore, new functional MRI sequences have been widely useful in determining the grade, heterogeneity and extent of BCBM. Some have even suggested that DTI might be used to aid in neurosurgical planning, radiotherapy preparation and monitoring of tumor recurrence and response to therapy.53 Although DTI has not been widely studied in clinical trial, many neurosurgeons actively use it to achieve an ideal resection without harming vital brain functions. Mapping functional centers in the brain and delineating their relationship to BCBM may improve neurosurgical outcomes.

The introduction of FLT as an imaging tracer for PET can be promising as it provides higher specificity than FDG in the presence of inflammation and high metabolic brain activity. Moreover, FLT can provide more input on BCBM biology before, during and after treatment. Nevertheless, other imaging modalities like MRI continue to have a cost-effective advantage. In the future, wider employment of newer modalities like single photon emission computed tomography–computed tomography (SPECT/CT) and PET/MRI can provide greater imaging resolution and diagnostic advantage.

Lately, ‘liquid biopsy’ has emerged as a novel minimally-invasive method for the molecular assessment of metastasis. Detection of CTCs and cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which is out of tumor cells, can be promising biosources that contain clinically valuable data.54

CTC quantification is already an established prognostic factor that is in trial for BCBM. The next frontier in CTC research is to elucidate their biology and characterization with advanced genomic techniques.55 This will help standardize detection and isolation of BCBM cells, and reveal the true clinical value of CTCs as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

In individuals with metastatic breast cancer, cfDNA that holds the mutations and methylation changes of its original tumor cell has been shown to be elevated.56–58 cfDNA, as a liquid-based diagnostic, possessed equal sensitivity and specificity of 87% for breast cancer.59 A meta-analysis further indicated that the plasma may be a good source of cfDNA for detection of breast cancer.59 In a case with HER2-positive BCBM, Siravegna et al.60 reported that cfDNA was more informative and sensitive than radiologic imaging. Nevertheless, detailed information on the volume measurements of brain metastases were missing. Bettegowda et al.61 showed that in cases of brain metastases, cfDNA, extracted from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), fluctuated as the variation in brain tumor burden changed over time. As such, CSF, which is more often in contact with the tumor, can be an effective source for genetic material.

Today, liquid biopsies may not be solely reliable neither for the diagnosis of BCBM nor for the stratification of patients for specific targeted therapies. Nonetheless, a combinatory diagnostic approach that involves the analyses of CSF, plasma and/or neuro-imaging may offer a more comprehensive description of the clinical case. Furthermore, liquid biopsy can potentially highlight specific genetic alterations that can ease the development of more personalized targeted therapies for patients with BCBM.

In the future, machine learning – a branch within AI – will have an important role in the diagnosis of BCBM and other brain tumors. Convolutional neural networks is a type of deep learning that can be used to swiftly analyze and process MRI results with efficiency and accuracy that can surpass that of human diagnosticians.62 This would save time and allow the physician to focus on optimizing patient treatment and bettering clinical outcomes.63, 64 In addition, recent studies have shown that the use of AI can help reduce the amount of contrast agents used in imaging, like gadolinium, while significantly improving the quality of MRI.65 This would prevent contrast-related toxicity and accumulation in brain tissue. Hopefully, ongoing research will pave the way for the use of intelligent machines in the diagnosis of metastatic brain tumors in a cost-effective manner.

Limitations

This study exclusively focuses on diagnostic trials in BCBM. We took ample precautions to avoid any bias or improper analyses by having two authors, independently, revise all trials identified and the trial selection steps. Some data might be registered incorrectly and/or missing in ClinicalTrials.gov; nevertheless, this analysis is distinctive and imperative as it paints a realistic image of the current status of BCBM diagnostic trials and offers researchers and clinicians the opportunity to reflect upon future BCBM diagnostic tools.

CONCLUSION

We presented an overview of current modalities in trial for the use in the diagnosis of BCBM. Current diagnostic clinical trials suffer from low accrual numbers and lack of published results. The development of new and innovative diagnostic tools for metastatic brain tumors is vital for early detection and treatment of BCBM. Neuroimaging continues to be at the forefront of the current array of diagnostic tools for BCBM. Advances in CTC and cfDNA detection and characterization hold promise in inferring the genetic and molecular groundworks of BCBM. The integration of AI and machine learning seems inevitable as we continue to aim for rapid and accurate detection of brain metastases and better patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R35CA197725 (M.S.L.), R01NS87990 (M.S.L., I.V.B.), R01NS093903 (M.S.L.), and 1R01NS096376–01A1 (A.U.A.), Lynn Sage Cancer Research Foundation (I.V.B), R21NS101150 (I.V.B), and R01NS106379 (I.V.B.).

ABBRREVIATIONS

- 18F

18-fluorine

- AI

artificial intelligence

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- BCBM

breast cancer brain metastases

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- cfDNA

cell-free DNA

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CT

computed tomography

- DTI

diffusion-tensor images

- EF5

18F-EF5

- ER

estrogen receptor

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FDG

fluorodeoxyglucose

- FLT

3’-deoxy-3’[18F]-fluorothymidine

- GATA3

GATA binding protein 3

- GCDFP-15

gross cystic disease fluid protein 15

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase

- Nal-IRI

nanoliposomal irinotecan

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography–computed tomography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Prevention CfDCa. Breast Cancer Statistics Vol 20182018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breastcancer.org. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics Vol 20182018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsukada Y, Fouad A, Pickren JW, Lane WW. Central nervous system metastasis from breast carcinoma. Autopsy study. Cancer 1983;52:2349–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klos KJ, O’Neill BP. Brain metastases. Neurologist 2004;10:31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AL, Haughton VM. Cranial computed tomography: a comprehensive text 1985.

- 6.Fares J, Fares MY, Fares Y. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Advances and impact in neuro-oncology. Surg Neurol Int 2019;10:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fares J, Fares MY, Fares Y. Natural Killer Cells in the Brain Tumor Microenvironment: Defining a New Era in Neuro-Oncology. Surg Neurol Int 2019;10:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gil-Gil MJ, Martinez-Garcia M, Sierra A, et al. Breast cancer brain metastases: a review of the literature and a current multidisciplinary management guideline. Clin Transl Oncol 2014;16:436–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. New Engl J Med 2001;344:783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyland-Jones B Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer and central nervous system metastases. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5278–5286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J, Kim J, Yoo E, Lee H, Chang JH, Kim EY. Detection of small metastatic brain tumors: comparison of 3D contrast-enhanced whole-brain black-blood imaging and MP-RAGE imaging. Invest Radiol 2012;47:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pope WB. Brain metastases: neuroimaging. Handb Clin Neurol 2018;149:89–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyhdalo KS, Booth CN, Brainard JA, et al. Utility of GATA3, mammaglobin, GCDFP-15, and ER in the detection of intrathoracic metastatic breast carcinoma. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology 2015;4:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker JE, Ross JS. Reporting Discrepancies Between the ClinicalTrials.gov Results Database and Peer-Reviewed Publications. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:760–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cihoric N, Tsikkinis A, van Rhoon G, et al. Hyperthermia-related clinical trials on cancer treatment within the ClinicalTrials.gov registry. Int J Hyperther 2015;31:609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, Sherman RE, Aberle LH, Tasneem A. Characteristics of Clinical Trials Registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007–2010. Jama-J Am Med Assoc 2012;307:1838–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fares J, Kanojia D, Cordero A, et al. Current State of Clinical Trials in Breast Cancer Brain Metastases. Neurooncol Pract 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kruger S, Mottaghy FM, Buck AK, et al. Brain metastasis in lung cancer. Comparison of cerebral MRI and 18F-FDG-PET/CT for diagnosis in the initial staging. Nuklearmedizin 2011;50:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Togao O, Hiwatashi A, Yamashita K, Kikuchi K, Yoshiura T, Honda H. Additional MR contrast dosage for radiologists’ diagnostic performance in detecting brain metastases: a systematic observer study at 3 T. Jpn J Radiol 2014;32:537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraum TJ, Ludwig DR, Bashir MR, Fowler KJ. Gadolinium-based contrast agents: A comprehensive risk assessment. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017;46:338–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kushnirsky M, Nguyen V, Katz JS, et al. Time-delayed contrast-enhanced MRI improves detection of brain metastases and apparent treatment volumes. J Neurosurg 2016;124:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anzalone N, Essig M, Lee SK, et al. Optimizing Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characterization of Brain Metastases: Relevance to Stereotactic Radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 2013;72:691–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szwarc P, Kawa J, Rudzki M, Pietka E. Automatic brain tumour detection and neovasculature assessment with multiseries MRI analysis. Comput Med Imag Grap 2015;46:178–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffith B, Jain R. Perfusion Imaging in Neuro-Oncology Basic Techniques and Clinical Applications. Magn Reson Imaging C 2016;24:765–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auerbach M, Chertow GM, Rosner M. Ferumoxytol for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia. Expert Rev Hematol 2018;11:829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasanawala SS, Nguyen KL, Hope MD, et al. Safety and technique of ferumoxytol administration for MRI. Magn Reson Med 2016;75:2107–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton BE, Nesbit GM, Dosa E, et al. Comparative Analysis of Ferumoxytol and Gadoteridol Enhancement Using T1-and T2-Weighted MRI in Neuroimaging. Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:981–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang MH, Wang J, Makena MR, et al. Activity of MM-398, Nanoliposomal Irinotecan (nal-IRI), in Ewing’s Family Tumor Xenografts Is Associated with High Exposure of Tumor to Drug and High SLFN11 Expression. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:1139–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramanathan RK, Korn RL, Raghunand N, et al. Correlation between Ferumoxytol Uptake in Tumor Lesions by MRI and Response to Nanoliposomal Irinotecan in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: A Pilot Study. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3638–3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones T, Rabiner EA. The development, past achievements, and future directions of brain PET. J Cerebr Blood F Met 2012;32:1426–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juhasz C, Dwivedi S, Kamson DO, Michelhaugh SK, Mittal S. Comparison of Amino Acid Positron Emission Tomographic Radiotracers for Molecular Imaging of Primary and Metastatic Brain Tumors. Mol Imaging 2014;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Patel SH, Robbins JR, Gore EM, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria (R) Follow-up and Retreatment of Brain Metastases. Am J Clin Oncol-Canc 2012;35:302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bollineni VR, Kramer GM, Jansma EP, Liu Y, Oyen WJG. A systematic review on [F-18]FLT-PET uptake as a measure of treatment response in cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer 2016;55:81–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffeth LK. Use of PET/CT scanning in cancer patients: technical and practical considerations. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005;18:321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson WR, Hay MP. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:393–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordsmark M, Bentzen SM, Rudat V, et al. Prognostic value of tumor oxygenation in 397 head and neck tumors after primary radiation therapy. An international multi-center study. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology 2005;77:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorwarth D, Eschmann S-M, Paulsen F, Alber M. Hypoxia dose painting by numbers: a planning study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komar G, Seppanen M, Eskola O, et al. 18F-EF5: a new PET tracer for imaging hypoxia in head and neck cancer. J Nucl Med 2008;49:1944–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koch CJ. Measurement of absolute oxygen levels in cells and tissues using oxygen sensors and 2-nitroimidazole EF5. Methods Enzymol 2002;352:3–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans SM, Judy KD, Dunphy I, et al. Comparative measurements of hypoxia in human brain tumors using needle electrodes and EF5 binding. Cancer Res 2004;64:1886–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heitz F, Harter P, Lueck H-J, et al. Triple-negative and HER2-overexpressing breast cancers exhibit an elevated risk and an earlier occurrence of cerebral metastases. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2009;45:2792–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vosjan MJ, Perk LR, Roovers RC, et al. Facile labelling of an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor Nanobody with 68Ga via a novel bifunctional desferal chelate for immuno-PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaneycken I, Devoogdt N, Van Gassen N, et al. Preclinical screening of anti-HER2 nanobodies for molecular imaging of breast cancer. FASEB J 2011;25:2433–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xavier C, Vaneycken I, D’Huyvetter M, et al. Synthesis, preclinical validation, dosimetry, and toxicity of 68Ga-NOTA-anti-HER2 Nanobodies for iPET imaging of HER2 receptor expression in cancer. J Nucl Med 2013;54:776–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 2011;331:1559–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ashworth T A case of cancer in which cells similar to those in the tumours were seen in the blood after death. Aust Med J 1869;14:146. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB, et al. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Survival Benefit from Treatment in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:6302–6309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baccelli I, Schneeweiss A, Riethdorf S, et al. Identification of a population of blood circulating tumor cells from breast cancer patients that initiates metastasis in a xenograft assay. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:539–U143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams SCP. Circulating tumor cells. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:4861–4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vona G, Sabile A, Louha M, et al. Isolation by size of epithelial tumor cells : a new method for the immunomorphological and molecular characterization of circulatingtumor cells. The American journal of pathology 2000;156:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jolesz FA, Dolati P, Talos IF, et al. Magnetic Resonance Image-Guided Neurosurgery. Handbook of Neuro-Oncology Neuroimaging, 2nd Edition. 2016:205–215. [Google Scholar]

- 53.da Cruz LCH, Kimura M. Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Brain Tumors. Handbook of Neuro-Oncology Neuroimaging, 2nd Edition. 2016:273–300. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rossi G, Mu Z, Rademaker AW, et al. Cell-Free DNA and Circulating Tumor Cells: Comprehensive Liquid Biopsy Analysis in Advanced Breast Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2018;24:560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plaks V, Koopman CD, Werb Z. Circulating Tumor Cells. Science 2013;341:1186–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Panagopoulou M, Karaglani M, Balgkouranidou I, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA in breast cancer: size profiling, levels, and methylation patterns lead to prognostic and predictive classifiers. Oncogene 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Schwarzenbach H, Hoon DSB, Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elshimali YI, Khaddour H, Sarkissyan M, Wu Y, Vadgama JV. The clinical utilization of circulating cell free DNA (CCFDNA) in blood of cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:18925–18958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu D, Tong Y, Guo X, et al. Diagnostic Value of Concentration of Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol 2019;9:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siravegna G, Geuna E, Mussolin B, et al. Genotyping tumour DNA in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of a HER2-positive breast cancer patient with brain metastases. ESMO Open 2017;2:e000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:224ra224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yasaka K, Abe O. Deep learning and artificial intelligence in radiology: Current applications and future directions. Plos Med 2018;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Fares Y, Fares J. Neurosurgery in Lebanon: History, Development, and Future Challenges. World Neurosurg 2017;99:524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fares Y, Fares J, Kurdi MM, Bou Haidar MA. Physician leadership and hospital ranking: Expanding the role of neurosurgeons. Surg Neurol Int 2018;9:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gong E, Pauly JM, Wintermark M, Zaharchuk G. Deep learning enables reduced gadolinium dose for contrast-enhanced brain MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018;48:330–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]