Abstract

Background

The origin of eukaryotic cells was an important transition in evolution. The factors underlying the origin and evolutionary success of the eukaryote lineage are still discussed. One camp argues that mitochondria were essential for eukaryote origin because of the unique configuration of internalized bioenergetic membranes that they conferred to the common ancestor of all known eukaryotic lineages. A recent paper by Lynch and Marinov concluded that mitochondria were energetically irrelevant to eukaryote origin, a conclusion based on analyses of previously published numbers of various molecules and ribosomes per cell and cell volumes as a presumed proxy for the role of mitochondria in evolution. Their numbers were purportedly extracted from the literature.

Results

We have examined the numbers upon which the recent study was based. We report that for a sample of 80 numbers that were purportedly extracted from the literature and that underlie key inferences of the recent study, more than 50% of the values do not exist in the cited papers to which the numbers are attributed. The published result cannot be independently reproduced. Other numbers that the recent study reports differ inexplicably from those in the literature to which they are ascribed. We list the discrepancies between the recently published numbers and the purported literature sources of those numbers in a head to head manner so that the discrepancies are readily evident, although the source of error underlying the discrepancies remains obscure.

Conclusion

The data purportedly supporting the view that mitochondria had no impact upon eukaryotic evolution data exhibits notable irregularities. The paper in question evokes the impression that the published numbers are of up to seven significant digit accuracy, when in fact more than half the numbers are nowhere to be found in the literature to which they are attributed. Though the reasons for the discrepancies are unknown, it is important to air these issues, lest the prominent paper in question become a point source of a snowballing error through the literature or become interpreted as a form of evidence that mitochondria were irrelevant to eukaryote evolution.

Reviewers

This article was reviewed by Eric Bapteste, Jianzhi Zhang and Martin Lercher.

Keywords: Eukaryogenesis, Mitochondria, Ribosomes, Bioenergetics, Major evolutionary transitions

Background

Lynch and Marinov [1] recently tabulated published values for the numbers of various molecules in cells in relationship to the cell volume with the aim of investigating the prokaryote to eukaryote transition. In the main, Lynch and Marinov [1] concluded from their calculations that “there is no reason to think membrane bioenergetics played a direct, causal role in the transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes and the subsequent explosive diversification of cellular and organismal complexity”. Their arguments claiming the evolutionary insignificance of mitochondria have been countered elsewhere [2], here the issue concerns irregularities in their published data. The keystone of their paper is a seemingly impressive list of values for the volumes of cells, their surface area, numbers of ATPases, and numbers of ribosomes per cell, numbers that are carefully tabulated in the supplementary information together with the corresponding references that serve as the paper’s foundation. Their paper and its underpinning supplementary information appear to be a rich source of useful numbers for calculations about various processes in cells, provided that the numbers are accurate. We checked.

Main text

The thrust of Lynch and Marinov’s [1] paper is a specific critique of a view attributable to one of us (WFM), namely that mitochondria were essential to the prokaryote-eukaryote transition [3, 4], therefore it is fair to inspect the strength of the data upon which the criticisms rest. In peer review, no one seems to have questioned whether their numbers were accurate. As we read Lynch and Marinov [1], we noticed that some of the numbers in Appendix 1-Tables 1–3 were conspicuously precise, often carrying up to eight significant digits for estimates of the numbers of ribosomes per cell or the volume of a cell in μm3. Do such values exist in the literature? Upon checking, we found that some form of systematic error underlies the paper by Lynch and Marinov [1].

Initially our attention was drawn to the number of cytosolic ribosomes for Tetrahymena pyriformis, reported as 7,490,000 [1] (Appendix 1-Table 3), which seemed very different from the value for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. We consulted Hallberg and Bruns [5] to which the value of 7,490,000 ribosomes per cell was attributed, but the only number in that paper containing the sequence of digits 7.49 is on page 385, Table 1, column 2, row 13; the number is not the number of ribosomes per cell, it is the value of an optical density measured at 259 nm (OD259) per million Tetrahymena cells. That spotcheck prompted further checks and it soon became apparent that a complete check of all the numbers in their Appendix 1-Table 3 was warranted. Appendix 1-Table 3 underlies Fig. 2 of Lynch and Marinov [1], which plotted cell volume against the number of ribosomes per cell and contained data points for 26 out of 27 species listed in Appendix 1-Table 3 (one of the species was not plotted, for unknown reasons). For two species, Vibrio angustum and Glycine max SB-1 cell, no values for cell volume were provided in Appendix 1-Table 3. All the other values in this table were checked in the original references and the results of this exercise are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Analysis of cell volumes and respective cited literature provided in Lynch and Marinov [1]

| Species | Volume (μm3) | Reference(s) cited | Location in cited reference1,2 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtillis | 1.407 | Barrera and Pan [14] | not present | The value reported is a range: 0.85-1.13 μm3 (p. S18, Table S-3, col. 4-5, rows 3-5). |

| Maass et al. [15] | not present | |||

| Escherichia coli | 0.983 | Bremer and Dennis [16] | not present | |

| Fegatella et al. [17] | not present | The value reported is 1.1 μm3 (p. 4434, col. 2, l. 30). | ||

| Bakshi et al. [18] | not present | The value reported is a range from 1.3-2.4 μm3 (p. S12, Fig S6). | ||

| Arfvidsson and Wahlund [19] | not present | |||

| Wisniewski et al. [20] | not present | |||

| Lu et al. [21] | not present | |||

| Legionella pneumophila | 0.58 | Leskelä et al. [22] | not present | |

| Leptospira interrogans | 0.22 | Beck et al. [23] | p. S10, col 1, l. 8 | |

| Schmidt et al. [24] | not present | |||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 0.05 | Yus et al. [25] | not present | The value in Maier et al. is from Hasselbring [29]. Still not plotted at 0.05 μm3 in Figure 2. |

| Seybert et al. [26] | not present | |||

| Kühner et al. [27] | not present | |||

| Maier et al. [28] | p. S3, col. 1, l. 5 | |||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 0.215 | Yamada et al. [30] | not present | |

| Rickettsia prowazekii | 0.089 | Pang and Winkler [31] | not present | The value reported is close but not the same: 0.09 μm3 (p. 117, Table 2, comment e.). |

| Sphingopyxis alaskensis | 0.05 | Fegatella et al. [17] | p. 4434, col. 2, l. 29 | |

| Spiroplasma melliferum | 0.018 | Ortiz et al. [32] | incorrect | L&M take the volume for a portion of the cell (p.339, col .1, l. 10). The volume reported for the whole cell is 34 times larger (p.339, col. 2, l. 16-18). |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0.288 | Martin and Iandolo [33] | not present | |

| Vibrio angustum | no value | Flärdh et al. [34] | ||

| ARMAN* | 0.03 | Comolli et al. [35] | p. 162, col. 2, l. 41 | |

| Exophiala dermatitidis* | 43.8 | Biswas et al. [36] | p. 137, Table 2, col. 7, row 2, 4 | L&M add the reported mean numbers for cell (36.0 ± 12.6 μm3) and cell wall (7.8 ± 2.5 μm3). |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 69.071 | Warner [37] | not present | The reported values are 17.1 μm3 for a cell in G1 and 13.3 μm3 for a cell in the early G1 (p.326, Table 2, l. 3). |

| Yamaguchi et al [38] | not present | |||

| Kulak et al. [39] | not present | |||

| Ghaemmaghami et al. [40] | not present | |||

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 118 | Marguerat et al. [41] | not present | The reported values are: cell length of 5-15 μm and cell diameter of 3.5 μm. p.322, col. 2, l. 24. |

| Maclean [42] | not present | |||

| Kulak [39] | not present | |||

| Tetrahymena pyriformis | 14002.067 | Hallberg and Bruns [5] | not present | |

| Tetrahymena thermophila | 7856.00 | Calzone et al. [43] | not present | |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | 151.00 | Bourque et al. [44] | not present | |

| Ostreococcus tauri* | 0.910 | Henderson et al. [45] | p. 3, col. 1, l. 7 | |

| Adonis aestivalis (vegetative) | 2380.3 | Lin and Gifford [46] | p. 2481, Table 2, col. 3, row 3-5 | L&M take the mean value for the vegetative apex of the central zone (2877), peripheral zone (924) and rib meristem (3340). |

| Adonis aestivalis (transitional) | 2287.00 | Lin and Gifford [46] | p. 2481, Table 2, col. 3, row 6-8 | L&M take the mean value for the vegetative apex of the transitional zone (1721), peripheral zone (1095) and rib meristem (4045). |

| Adonis aestivalis | 2690.00 | Lin and Gifford [46] | p. 2481, Table 2 col. 3, row 9-11 | L&M take the mean value for the vegetative apex of the floral zone (2380), peripheral zone (802) and rib meristem (4888). |

| Glycine max SB-1 cell | no value | Jackson and Lark [47] | ||

| Rhus toxicodendron* | 1222.00 | Vassilyev [48] | p.617, Table 2, col 2-3, row 1 | L&M take the mean value of the whole cell for procambial stage (1028), rough ER stage (1130) and smooth ER stage (1508). |

| Zea mays root cell | 240,000 | Hsiao [49] | not present | The value appears in the literature but not in Hsiao [49], but rather in Hsiao [50] p.105, Table 1, col. 3, row 4-5. |

| Hamster, intestinal enterocyte* | 1890.00 | Buschmann and Manke [51, 52] | p. 16, Table 1, col. 2, row 6 | In Buschmann and Manke [52]. |

| HeLa Cell | 2798.668 | Duncan and Hershey [53] | not present | The reported value is 2600 μm3. p.163, col. 2, l. 35. |

| Zhao et al. [54] | not present | |||

| Kulak et al. [39] | not present | |||

| Mouse pancreas* | 1434.00 | Dean [55] | p. 117, Table 2, col. 6, row 2 | |

| Rat liver cell* | 4940.00 | Weibel et al. [56] | p. 80, Table 2, col. 10, row 2 |

1‘S’ refers to Supplemental Material

2not present - value cannot be found in the cited paper; incorrect - a wrong value was taken from the cited paper

*Species with both volume and ribosome count values verified

Table 2.

Analysis of ribosome numbers and respective cited literature provided in Lynch and Marinov [1]

| Species | Ribosome number | Reference(s) cited | Location in cited reference1,2 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | 6000 | Barrera and Pan [14] | p. 485, col. 1, l. 30 | |

| 9124 | Maass et al. [15] | incorrect | L&M take the average of the quantification for the four ribosomal proteins for which there is data in this study, in all three time points. However, rplL should be scaled down as it is present in 4 copies per ribosome3. | |

| Escherichia coli | 72000 | Bremer and Dennis [16] | p. 9, Table 3, col. 8, row 24 | |

| 45100 | Fegatella et al. [17] | p. 4437, Table 3, col. 4, row 9 | ||

| 26300 | Fegatella et al. [17] | p. 4437, Table 3, col. 4, row 8 | ||

| 13500 | Fegatella et al. [17] | p. 4437, Table 3, col. 4, row 7 | ||

| 6800 | Fegatella et al. [17] | p. 4437, Table 3, col. 4, row 6 | ||

| 55000 | Bakshi et al. [18] | p. 26, col. 2, l. 13 | ||

| 20100 | no reference provided | |||

| 12000 | Arfvidsson and Wahlund [19] | not present | L&M seem to have extrapolated the value from Figure 5, p. 82, however the figure shows a range of ca. 2500-13000. | |

| 6514 | Wiśniewski et al. [20] | not present | The citation seems to be incorrect. No reference to E. coli in the citation. | |

| 17979 | Lu et al. [21] | incorrect | L&M take the average of the quantification of all rpl and rps proteins but exclude rpm proteins. Also, rpl should be scaled down as it is present in 4 copies per ribosome3. | |

| Legionella pneumophila | 7400 | Leskelä et al. [22] | p. 174, col. 2, l. 24 | |

| Leptospira interrogans | 4500 | Beck et al. [23] | p. 820, Table 1, col. 2, l. 3 | L&M use 4500, which is one number in the range reported: 3400, 3500, 4500. Considering standard deviations, the range reported is 2800-5000. |

| 1039 | Schmidt et al. [24] | incorrect | L&M take the average of the quantification of all ribosomal proteins for the first time-point of the serum treatment (same value for the doxycycline treatment). The range of averages for all time points and all treatments is 537-2170. The range for the serum treatment is 537-1039. | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 140 | Yus et al. [25] | p. S14, col. 1, l. 23 | Yus et al. cite their value from “Kuhner et al. accompanying manuscript”. |

| 300 | Seybert et al. [26] | p. 351, col. 1, l. 39 | ||

| 422 | Kühner et al. [27] | p. S38, Figure S9B, l. 9 | L&M use the values of the Western Blot estimation. The electron tomography results of the same citation indicate 140 | |

| 225 | Maier et al. [28] | incorrect | L&M take the mean of all values in Table S7 column “direct quantified (copies per cell)”. However, RPL7 needs to be scaled down as it is present more than once per ribosome3. | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1672 | Yamada et al. [30] | p. 9, Table 4, col. 4, row 7 | |

| Rickettsia prowazekii | 1500 | Pang and Winkler [31] | p. 117, Table 2, col. 2, row 6 | |

| Sphingopyxis alaskensis | 1850 | Fegatella et al. [17] | not present | |

| 200 | Fegatella et al. [17] | p. 4435, col. 1, l. 27 | The value reported is 2000 (p. 4435, col. 1, l. 24). | |

| Spiroplasma melliferum | 275 | Ortiz et al. [32] | incorrect | L&M take the number of ribosomes for a portion of the cell. The number reported for the whole cell is 1000 (p.339, col. 2, l. 20). |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 54400 | Martin and Iandolo [33] | p. 1139, Table 1, col. 2-3, l. 9 | L&M take the mean of estimated ribosomes per cell in rich and poor medium: 83200 (col. 2, row 11); 25600 (col. 3, row 11). |

| Vibrio angustum | 27500 | Flärdh et al. [34] | p. 6783, col. 1, l. 13 | L&M take the mean of two counts: 20000 and 35,000. |

| 8000 | Flärdh et al. [34] | p. 6783, col. 1, l. 14 | The reported value is after 4 days of starvation. Value for 24h of starvation (16000) not included. | |

| ARMAN* | 92 | Comolli et al. [35] | p. 162, col. 2, l. 41 | |

| Exophiala dermatitidis* | 195000 | Biswas et al. [36] | p. 137, Table 1, col. 7, row 6 | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 200000 | Warner [37] | p. 437, col. 1, l. 34 | |

| 220000 | Yamaguchi et al. [38] | incorrect | L&M take the value from the abstract, which is an approximation. The reported value is 217000 (mean for G1 cells - p.325, Table 1, col. 5, row 11). | |

| 153456 | Kulak et al. [39] | not reproducible | Not clear how the value was calculated. | |

| 72284 | Ghaemmaghami et al. [40] | not reproducible | Not clear how the value was calculated. | |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 150000 | Marguerat et al. [41] | p. 677, col. 1, l. 35 | |

| 500000 | Maclean [42] | p. 323, col. 1, l. 66 | ||

| 505260 | Kulak [39] | not reproducible | Not clear how the value was calculated. | |

| 100568 | Marguerat et al. [41] | not reproducible | Not clear how the value was calculated. | |

| Tetrahymena pyriformis | 7490000 | Hallberg and Bruns [5] | incorrect | L&M take the reported number from p. 385, table 1, col. 2, row 1, which is 7.49 OD259 per 106 cells. |

| Tetrahymena thermophila | 74000000 | Calzone et al. | p. 6892, Table 3, | L&M take the mean of ribosomes per cell of log phase (10.8 x107) and starved cells (4.0 x107). |

| [43] | col. 2-3, row 4 | |||

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (chloroplast) | 120500 | Bourque et al [44] | p. 157, Table 2, col. 9 row 3-4 | L&M take the mean of values of cytoplasmic ribosomes per hypothetical cell for the two growth conditions for wildtype cells (0.98x105 and 1.43x105). |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (chloroplast) | 55,000 | Bourque et al. [44] | p. 157, Table 2, col. 10, row 3–4 | L&M take the mean of the values of chloroplast ribosomes per hypothetical cell for the two growth conditions for wildtype cells (0.53 × 105 and 0.57 × 105). |

| Ostreococcus tauri * | 1250 | Henderson et al. [45] | p. 10, col. 2, l. 43 | |

| Adonis aestivalis (vegetative) | 47700000 | Lin and Gifford [46] | p. 2481, Table 3, col. 4, row 2-4 | L&M take the mean of the total number of ribosomes per cell (in millions) for the vegetative apex: central zone (40.2), peripheral zone (25.7) and rib meristem (77.2). |

| Adonis aestivalis (transitional) | 39066666 | Lin and Gifford [46] | p. 2481, Table 3, col. 4, row 5-7 | L&M take the mean of the total number of ribosomes per cell (in millions) for the transitional apex: central zone (34.2), peripheral zone (31.1) and rib meristem (51,9). |

| Adonis aestivalis (floral) | 23666666 | Lin and Gifford [46] | not present | The mean of the total number of ribosomes per cell (in millions) for the floral apex is 23.9; central zone (30.9), peripheral zone (18.8), rib meristem (22.1). |

| Glycine max SB-1 cell | 9373333 | Jackson and Lark [47] | p. 236, Table 1, col. 4, row 3-5 | L&M take the mean of ribosomes per cell for SB-1 cells in sucrose (9530000), M-24 cells in maltose (7190000) and M- 200 cells in sucrose (11400000); L&M exclude M-200 cells in maltose. |

| Rhus toxicodendron* | 2400000 | Vassilyev [48] | p. 620, Table 4, col. 2–4, row 6 | L&M take the mean of the added numbers for cytoplasmic ribosomes per whole epithelial cell from the procambium stage (free 3260000 and bound 480000) and the SER stage (free 810000 and bound 250000). |

| Zea mays root cell | 25500000 | Hsiao [49] | not present | The value appears in the literature but not in Hsiao (1970a), but rather in Hsiao (1970b) p.105, Table 1, col. 4, row 4-5. |

| Hamster, intestinal enterocyte* | 1500000 | Buschmann and Manke [51, 52] | p. 23, Figure 5 | In Buschmann and Manke (1981b). L&M take the mean of total ribosomes per average enterocyte for fasted and lipid-fed cells. |

| HeLa Cell | 3300000 | Duncan and Hershey [53] | p. 7229, col. 1, l. 73 | Not clear how the value was calculated. |

| 5748830 | Kulak et al. [39] | not reproducible | ||

| no value | Zhao [54] | |||

| Mouse pancreas* | 1340000 | Dean [55] | 117, Table 2, col. 6, row 12 | |

| Rat liver cell* | 12700000 | Weibel et al. [56] | p. 80, Table 2, col. 10, row 12 |

1‘ S’ refers to Supplemental Material

2not present - value cannot be found in the cited paper; incorrect - a wrong value was taken from the cited paper; not reproducible – calculations derived from proteomics study cannot be reproduced

3(Ilag et al. [57]; Gordiyenko et al. [58]; Garcia et al. [59])

*Species with both volume and ribosome count values verified

Tables 1 and 2 list on a case-by-case basis which numbers are to be found in the literature underpinning Lynch and Marinov’s Fig. 2. For the 80 values reported in Lynch and Marinov’s Appendix 1-Table 3, the most common problem we encountered is that the corresponding number does not exist (is nowhere to be found) anywhere in the paper to which it is attributed or the corresponding supplement when present. For 48 of the 80 individual values (60%) that Lynch and Marinov [1] report for cell volume vs. ribosome number, the value for the corresponding parameter is either i) not present in the cited paper ii) incorrect (a wrong value was taken from the cited paper) or iii) not reproducible (calculations derived from proteomics study that cannot be reproduced). Such cases are scored accordingly in Tables 1 and 2. All cases in which a different number is given in the cited source than that reported by Lynch and Marinov [1], are reported individually in Tables 1 and 2 for inspection. In those cases where a number was reported for the corresponding parameter, we have listed the page, the column, and the line number where the number appears.

In some cases, the numbers in Lynch and Marinov [1] are only slightly different from those reported, but the nature of those differences remains elusive. For example, Lynch and Marinov report the volume of Hela cells as 2798.668 μm3 (accuracy to 1/1000th of a μm3) citing three references, only one of which however reports the corresponding parameter, yet as 2600 μm3 (two significant digits). In that minority of cases where we were able to confirm the numbers reported by Lynch and Marinov [1], we have given the specific location as witness of the number’s existence.

In terms of content, Lynch and Marinov [1] distill from their analyses as their major final conclusion that their findings support the suggestion of Pittis and Gabaldon [6] that eukaryote complexity arose by piecemeal lateral gene transfer from prokaryotes (which lack the complexity they purportedly donated). It needs to be stated that the analyses of Pittis and Gabaldon [6] themselves are ridden with artifacts [7], most notably a classic case of overfitting data to a highly parameterized model (five Gaussian distributions) when a simpler model (a lognormal distribution) far better accounts for the data. Lynch and Marinov [1] also suggest that phagocytosis might have come late in eukaryotic evolution, which is hardly a novel suggestion [3, 8].

For the 26 data points presented in Fig. 2 of Lynch and Marinov, 73% are not supported by the numbers they published. The data points for one archaeon, one yeast, one unicellular alga, one plant, mouse, hamster and rat remain (marked with * in Tables 1 and 2). It is well known that ribosomes are a main constituent of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells by weight, as cells devote about 75% of their energy budget to protein synthesis on ribosomes [4, 9].

The problem with the Lynch and Marinov paper is twofold. First, future researchers will either use those numbers from Appendix 1-Table 3 of Lynch and Marinov [1], even though they are incorrect, or worse, researchers might take the numbers presented by Lynch and Marinov and attribute them directly to the cited papers in which the numbers — in one case even the species for which the numbers are given — do not appear (Tables 1 and 2). Lynch and Marinov will thus be the point source of snowballing error through the literature.

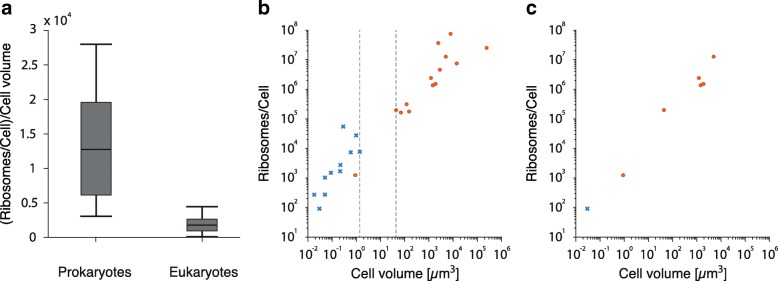

Furthermore, Lynch and Marinov argue that “the numbers of ribosomes per cell also appear to scale sublinearly with cell volume, in a continuous fashion across bacteria, unicellular eukaryotes, and cells derived from multicellular species” [1]. In other words, Lynch and Marinov imply that there is a continuum rather than a divide between prokaryotes and eukaryotes regarding the ribosome count per cell and cell volume. However, a Wilcoxon ranksum test fails to accept the null hypothesis that the prokaryotic and eukaryotic ‘ribosomes per cell/cell volume’-ratios are both part of the same continuous distribution (Fig. 1a, ρ=0.0003). For this test, no values of their Appendix 1-Table 3 were altered or excluded. A simple visual inspection shows a clear divide between eukaryotic and prokaryotic data points (Fig. 1b). Excluding the smallest known autotrophic eukaryote Ostreococcus tauri (possessing a highly reduced genome), there is a gap of approximately 1.5 orders of magnitude between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell volumes while ribosomes per cell only increase approximately 3-fold between representatives of the two kingdoms.

Fig. 1.

Ribosomes per cell and cell volume. a Boxplots of the distribution of prokaryotic and eukaryotic ‘ribosomes per cell and cell volume’-ratios. The Wilcoxon ranksum test rejected the null hypothesis that the eukaryotic and prokaryotic samples are part of the same continuous distribution with ρ=0.0003. b Ribosomes per cell versus cell volume. Blue crosses: Prokaryotes. Orange circles: Eukaryotes. Excluding Ostreococcus tauri, there is a gap of approximately 1.5 orders of magnitude between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell volumes, indicating the fundamental differences in prokaryotic and eukaryotic nature. All values were taken from Lynch and Marinov [1] Appendix 1-Table 3. c Replot of Fig. 1b, only showing data points where both cell volume and the number of ribosomes per cell could be verified by the provided references in Lynch and Marinov [1]

That is not the main problem, though, and our aim is not to challenge Lynch and Marinov’s inferred sublinear scaling. Rather, the point is this. Their correlations are based on values that cannot be sourced to their references, as we outline in the following. We examined 80 of the 246 literature values reported by Lynch and Marinov. More than half of the numbers we examined were modified from the literature or nonexistent there; in some cases, the numbers were the mean, sometimes the maximum from a range, sometimes the mean after some values had arbitrarily been excluded, the most common problem being that the cited literature lacked the number altogether (Tables 1 and 2). The underlying error pattern is irregular, and only seven data points remain in the plot after our inspection (Fig. 1c). But that is still not the main problem. There are 166 other values reported in Appendix 1-Tables 1 and 2 in Lynch and Marinov [1] that we did not check, because it is not our responsibility to mend the flaws in published critiques of our work with a posteriori scholarship, which should have been supplied by author-borne academic standards and rigorous peer review. Tables 1 and 2 provide no reason to trust that their other 166 numbers are any more accurate than the 80 that we inspected. Hence it is currently not possible to independently ascertain how half the numbers that Lynch and Marinov [1] ushered into print were generated and from what source they were gleaned.

This is not the first time that a paper by Lynch and Marinov has been flagged. In 2015, Lynch and Marinov [10] reported calculations for the energetic cost of a gene when in fact the issue was not about the cost of a gene (energy demands) rather about energy supply [11]. Now they argue that prokaryotes and eukaryotes represent a continuous distribution of cellular size [1] and by inference, complexity, although the converse is true (Fig. 1b). But we return to their main point, namely their claim that “there is no reason to think membrane bioenergetics played a direct, causal role in the transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes”. There are indeed such reasons [2], it is worthwhile to recapitulate them briefly.

The issue is the evolutionary origin of cellular complexity [4]. Mitochondrial respiration was present in the eukaryote common ancestor [2–4]. Why? Eukaryotes and prokaryotes generate the same amount of energy per unit volume [4]. In prokaryotes, chemiosmotic energy conservation occurs at the plasma membrane, in eukaryotes it occurs in mitochondria, which however constitute only about 10% of the cell volume [12]. That is why eukaryotic cell size is not evolutionarily constrained, while prokaryotic cell size is [2, 4]. It is also why human mitochondria operate at about 50 °C [13], they provide the energy for the remaining 90% of the cell, which is cytosol [2] consisting of 400 mg/ml protein. Mitochondria afford eukaryotes the ability to explore the (over)expression of novel proteins in that cytosol, an option that prokaryotes do not have [2].

Conclusion

Lynch and Marinov might wish to follow our example of providing the page, column, and line, for the position of all 246 numbers that they attribute to the literature and explain how each value was determined from which selected range of numbers (and excluding which) in the original literature they cite. For a sample of one third of the values underpinning the paper by Lynch and Marinov [1], more than 50% of the numbers fail independent inspection, are not to be found in the cited literature, and hence cannot have been checked by either author prior to publication. The source of their numbers is obscure. This paper was originally submitted to eLife and rejected. During revision of this paper, a correction of the original paper by Lynch and Marinov [1] was published. The original version of their paper (including Appendix 1-table 3, Figure 2 and its caption) is no longer available at eLife, but can still be obtained here: http://www.molevol.de/LM2017.pdf.

Methods

MG obtained the papers cited by Lynch and Marinov [1] that underlie their Fig. 2 and read the papers in search of the values. Her results were spot checked by WFM, then each number was thoroughly checked, one by one, first by MK and JX, then again by NK and JX. The results of that fact checking were scored in Tables 1 and 2, where it was recorded whether the numbers presented by Lynch and Marinov could be confirmed (stating page, column, and line), whether different numbers for the corresponding parameter or a range were presented (stating page, column, and line), or whether the number was not present in the paper cited. For the Wilcoxon ranksum test, all values were collected from Appendix 1-Table 3 of Lynch and Marinov [1]. No values have been excluded nor altered in any way.

Reviewers’ comments

Reviewer’s report 1: Eric Bapteste, CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France

Reviewer comment: Debates about theories and about evidence backing up these theories are the norm (and, as a pluralist, I would even say are welcome) in any active research field. If anything, they keep a field alive, and stimulate original thoughts. Hence, I sincerely admire both Bill Martin’s and Michael Lynch’s numerous inspiring contributions to evolutionary biology. Martin’s present article precisely questions the validity of the quantitative evidence used by Lynch and Marinov (hinting at the repeated use of averaged values, and reporting several values without clear bibliographical origins). I agree that this situation is frustrating, and I think that, ideally, doubts raised about some of these numbers should be explicitely addressed. I suggest that a journal like Biology Direct could be a good venue to publish an updated version of the incriminated tables, in a way that clarifies the origins of some of the evidence used by Lynch and Marinov, and, as an avid reader of both Martin’s and Lynch’s works, I would even hope that these updated numbers could then be used to update computations about energetics, to determine whether such (carefully checked) numbers do or do not impact Lynch and Marinov’s former conclusions.

Author’s response: We thank R1 for the endorsement of our paper. We share the expectation to see a corrected version of the tables by Lynch and Marinov, clearly sourced (including, as we did here, page, column and row of the cited source for the given values).

Reviewer comment: The criticisms on Pittis and Gabaldon’s article also seem somehow out of place in the present MS.

Author’s response: We must politely disagree in this regard. We believe it is well-worth noting that a common trend seems to be emerging in the community, a trend of misuse of statistics in extrapolations on complex biological questions. We hope that our criticism can point to the importance of both i) the collection of more well-sourced, quality data and ii) a pondered use of statistics as a tool, not as an end, in biology.

Reviewer’s report 2: Jianzhi Zhang, EEB, University of Michigan, MI, U.S.A.

Reviewer comment: There is an ongoing debate on the role of energy production by mitochondria in the origin of eukaryotes and their subsequent diversification. In 2017, Lynch and Marinov published an article in eLife suggesting that eukaryotes are energetically no more efficient than prokaryotes. Because their empirical evidence is based on the analysis of various data from the literature, the accuracy of these data is critical to their conclusion. In the present manuscript, Gerlitz et al. systematically examined the sources of the data used by Lynch and Marinov. They report that most of the data cannot be found in the references where the data were claimed to be from or were different from the values in these references. Although the causes of these discrepancies are unclear, it is important to alert the research community the potential invalidity of Lynch and Marinov’s conclusion by publishing these discrepancies. I must say that I do not believe that reviewers are responsible for the accuracy of the data in a paper, so I have not closely examined the numbers in the two tables of the present manuscript. While Lynch and Marinov should be responsible for the accuracy of their paper, Gerlitz and colleagues bear the responsibility for this manuscript. My two major comments and a minor comment follow.

Author’s response: We thank R2 for sharing our concern with the importance of the accuracy of published data. We hereby confirm that we bear full responsibility for the content of this manuscript.

Reviewer comment: Major: 1. Because a large fraction of the data in Lynch and Marinov cannot be verified by Gerlitz et al., I wonder if the general trends reported by Lynch and Marinov also disappear. Specifically, it will be interesting to replot the two figures in Lynch and Marinov using the verified portion of the data. I understand that whether the data used are sound and whether the results are robust are different issues, and I think Gerlitz et al. can address both issues in this work.

Author’s response: This is a good point to which we have given considerable thought. The problem is that the values that stand upon our close inspection are so few as to produce an almost empty plot. Only one prokaryotic data point survives the inspection. We believe that the correction of the values needs to be provided by Lynch and Marinov, either as a corrigendum or in a new paper, it is not our duty to correct their paper. We intend here to alert the community to the inaccuracy of the data provided by Lynch and Marinov. We would also like to see more data points added, rather than just a handful of species, in order to sustain such bold claims.

Nonetheless, for fairness we provide an additional plot showing the data points that were accurately attributed in Lynch and Marinov 2017 as Fig. 1c, it clearly does not impinge upon our observation that the values for prokaryotic and the eukaryotic cells plotted by Lynch and Marinov 2017 are drawn from distinct distributions.

Reviewer comment: 2. Gerlitz et al. made a point in Fig. 1 that prokaryotes and eukaryotes differ by 1.5 orders of magnitude and showed a significant p-value from a Wilcoxon ranksum test. If my understanding is correct, this test result indicates that ribosomes concentration (# of ribosomes/cell/cell volume) is lower in eukaryotes than in prokaryotes. However, this is not what Lynch and Marinov argued about in the corresponding Fig. 2 of their paper. Lynch and Marinov’s Fig. 2 argues that the general scaling relationship between # of ribosome per cell and cell volume is not different between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Only when the scaling factor is 1 will ribosome concentration be constant, and the scaling factor is 0.79 according to Lynch and Marinov. In other words, Lynch and Marinov and Gerlitz et al. do not disagree here.

Author’s response: This is a fair point. However, we wish only to show, that contrary to Lynch and Marinov’s claims, even when using their (cryptic) data, the power law they describe does not come from a continuous distribution. The issue of continuity is key. As they say: “[…] the numbers of ribosomes per cell also appear to scale sublinearly with cell volume, in a continuous fashion across bacteria, unicellular eukaryotes, and cells derived from multicellular species ”. They state it again later “The numbers of both ribosomes and ATP synthase complexes per cell, which jointly serve as indicators of a cell’s capacity to convert energy into biomass, scale with cell size in a continuous fashion both within and between bacterial and eukaryotic groups”. Both of our figures show that this is not the case. This criticism brings out a very good point, actually. We return to this point later in a reply to Martin Lercher. The issue of continuity is now addressed more explicitly in the revised text to underscore this important point.

Reviewer’s report 3: Martin Lercher, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany

Reviewer comment: Gerlitz et al. checked the values (cell volume and ribosome counts) underlying Fig. 2 in Lynch & Marinov (2017, abbreviated LM below) against the reported literature sources. They could not find a large fraction of the reported cell volume values, while many of the ribosome counts were calculated as averages over sets of reported values according to an undisclosed (or non-existent) algorithm by Lynch & Marinov. Gerlitz et al. conclude that the data in Lynch & Marinov (2017) does not conform to scientific standards. After carefully going through the problems with the LM data reported by Gerlitz et al., I have to agree that the standards of data collection employed by LM do not conform to current scientific standards. While it is not clear to what extent the data is factually wrong (within some acceptable margin of error), the lack of a clear standard according to which LM obtained those data is reason for concern. No experimental work that employed similarly loose algorithms to arrive at data values would (or should) be considered for publication in a peerreviewed journal.

Author’s response: We thank R3 for sharing our concerns with the quality standards of published data and analysis.

Reviewer comment: p.7 l.164: “a Wilcoxon ranksum test fails to accept the null hypothesis that the prokaryotic and eukaryotic ‘ribosomes per cell/cell volume’-ratios are both part of the same continuous distribution (Fig. 1a …).” That prokaryotic and eukaryotic ‘ribosomes per cell/cell volume’-ratios are both part of the same continuous distribution is not what was stated by LM. Instead, they state that a power-law relationship can be fitted successfully to the ribosome count/cell versus cell size data. Thus, Fig. 1a and the Wilcoxon test do not address a hypothesis posited by LM, and I would recommend removing both.

Author’s response: As summarized in our reply to Referee 2, Lynch and Marinov do state in the Results and Discussion sections of their paper, “[…] the numbers of ribosomes per cell also appear to scale sublinearly with cell volume, in a continuous fashion across bacteria, unicellular eukaryotes, and cells derived from multicellular species (Fig. 2)” and that “The numbers of both ribosomes and ATP synthase complexes per cell […] scale with cell size in a continuous fashion both within and between bacterial and eukaryotic groups”. What we see in their (cryptic) data is not a continuous scaling, but a clear divide between the average concentration of ribosomes of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

Reviewer comment: p.7 l.171: “there is a gap of approximately 1.5 orders of magnitude between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell volumes while ribosomes per cell only increase approximately 3-fold between representatives of the two kingdoms”. Another, more rigorous way of looking at this issue would be to fit two independent power laws (linear fits on log-log scale) to the prokaryotic and to the eukaryotic data, and to see if (a) these two power laws are significantly different, and (b) if the data is more appropriately described by two rather than one power law.

Author’s response: We agree that it would be interesting to look at two power laws independently. However, for that to be done accurately we would require the correct, well-sourced values that we show that Lynch and Marinov failed to provide. We believe it is not our duty to correct the values of Lynch and Marinov. We look forward to seeing them providing such analyses, and if possible more data points than a handful of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, to make such bold claims. We agree that the analysis that Referee 3 suggests would be a much better approach for sustaining such conclusions. There is a danger in just comparing R 2 values of the three power-laws though, but we believe this is not the place to advise Lynch and Marinov about which methods they should use in future papers.

Reviewer comment: Table 2. Many of the values reported as “not present” by the authors are – as inverse engineered by the authors and stated in the comments – mean values of proteomic estimates for different ribosomal subunits. This was actually stated by LM in the header of appendix1-Table 3: “proteomic estimates are from averaging of cell-specific estimates for each ribosomal protein subunit”, so I would consider the label “not present” as inappropriate (even if the exact calculations are frequently incorrect, as pointed out in the comments in Table 2).

Author’s response: This is a good point. We used “not present” as a standard tag for values that could not be found in the cited reference, were incorrect, or could not be reproduced properly. We now use all three, more specific tags: “not present”, “incorrect” and “not reproducible”.

Reviewer comment: I have only one remaining concern. It relates to the statement by Lynch and Marinov: “the numbers of ribosomes per cell also appear to scale sublinearly with cell volume, in a continuous fashion across bacteria, unicellular eukaryotes, and cells derived from multicellular species”. The choice of the word “continuous” here is unfortunate; it probably refers to the observation that a line drawn through the data in A can be continued through the data in B. Let us define x:=“cell volume”, y:=“the number of ribosomes per cell”. What Gerlitz et al. test (l.170ff) is the null hypothesis that y/x for data in bacteria and in eukaryotes come from the same distribution. This would be appropriate if Lynch and Marinov had observed a linear scaling, y = c*x. However, Lynch and Marinov explicitly state that there is a sub-linear scaling: in the legend to Fig. 2, they give the inferred relationship as y = 8551*x^0.79. Thus, to show disagreement with Lynch and Marinov, Gerlitz et al. would have to compare the distributions of y/(x^0.79) instead of comparing the distributions of y/x between bacteria and eukaryotes.

Author’s response: The point is well taken and has been addressed in the main text.

Acknowledgements

We thank friends and colleagues as well as the members of the group in Düsseldorf for discussion and constructive input.

Funding

WM thanks the ERC (666053), the German-Israeli Foundation (I-1321-203.13/2015), and the Volkswagen Foundation (Life, 93 046) for financial support.

Availability of data and materials

All checked references of Lynch & Marinov [1] can be downloaded from the respective journal’s websites.

Abbreviations

- ATPase

Adenosin triphosphatase

- OD

Optical density

Authors' contributions

WFM conceived the study, MG, MK, NK, and JX generated Tables 1 and 2, WFM wrote the first draft, all authors wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that we do not have competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Marie Gerlitz and Michael Knopp contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Marie Gerlitz, Email: marie.gerlitz@hhu.de.

Michael Knopp, Email: michael.knopp@hhu.de.

Nils Kapust, Email: nils.kapust@hhu.de.

Joana C. Xavier, Email: xavier@hhu.de

William F. Martin, Email: bill@hhu.de

References

- 1.Lynch M, Marinov GK. Membranes, energetics, and evolution across the prokaryote-eukaryote divide. elife. 2017;6:e20437. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin WF. Symbiogenesis, gradualism, and mitochondrial energy in eukaryote origin. Period Biol. 2017;119:141–158. doi: 10.18054/pb.v119i3.5694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin WF, Müller M. The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote. Nature. 1998;392:37–41. doi: 10.1038/32096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane N, Martin WF. The energetics of genome complexity. Nature. 2010;467:929–934. doi: 10.1038/nature09486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallberg RL, Bruns PJ. Ribosome biosynthesis in Tretrahymena pyriformis. Regulation in response to nutritional changes. J Cell Biol. 1976;71:383–394. doi: 10.1083/jcb.71.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittis AA, Gabaldón T. Late acquisition of mitochondria by a host with chimaeric prokaryotic ancestry. Nature. 2016;531:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature16941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin WF, Roettger M, Ku C, Garg SG, Nelson-Sathi S, Landan G. Late mitochondrial origin is an artifact. Genome Biology and Evolution. 2017;9:373–379. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould SB, Garg SG, Martin WF. Bacterial vesicle secretion and the evolutionary origin of the eukaryotic endomembrane system. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harold FM. The vital force: a study of bioenergetics. New York: W H Freeman & Co; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch M, Marinov GK. The bioenergetic cost of a gene. PNAS. 2015;112:15690–15695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421641112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane N, Martin WF. Mitochondria and evolutionary deficit spending. PNAS. 2016;113:E666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522213113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenchel T. Respiration in heterotrophic unicellular eukaryotic organisms. Protist. 2014;165:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chrétien D, Bénit P, Ha HH, Keipert S, El-Khoury R, Chang YT, Jastroch M, Jacobs HT, Rustin P, Rak M. Mitochondria are physiologically maintained at close to 50 °C. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2003992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrera A, Pan T. Interaction of the Bacillus subtilis RNase P with the 30S ribosomal subunit. RNA. 2004;10:482–492. doi: 10.1261/rna.5163104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maass S, Sievers S, Zühlke D, Kuzinski J, Sappa PK, Muntel J, Hessling B, Bernhardt J, Sietmann R, Völker U, Hecker M, Becher D. Efficient, global-scale quantification of absolute protein amounts by integration of targeted mass spectrometry and two-dimensional gel-based proteomics. Anal Chem. 2011;83:2677–2684. doi: 10.1021/ac1031836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bremer H, Dennis PP. Modulation of chemical composition and other parameters of the cell by growth rate. In: Neidhardt FC. Escherichia Coli and Salmonella Typhimurium. Cellular and molecular biology; 1996. Vol. 97, 2nd edn. P 1559.

- 17.Fegatella F, Lim J, Kjelleberg S, Cavicchioli R. Implications of rRNA operon copy number and ribosome content in the marine oligotrophic ultramicrobacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RB2256 Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64:4433–4438. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4433-4438.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakshi S, Siryaporn A, Goulian M, Weisshaar JC. Superresolution imaging of ribosomes and RNA polymerase in live Escherichia coli cells. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85:21–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arfvidsson C, Wahlund KG. Time-minimized determination of ribosome and tRNA levels in bacterial cells using flow field-flow fractionation. Anal Biochem. 2003;313:76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2697(02)00541-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiśniewski JR, Hein MY, Cox J, Mann MA. “Proteomic ruler” for protein copy number and concentration estimation without spike-in standards. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:3497–3506. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.037309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu P, Vogel C, Wang R, Yao X, Marcotte EM. Absolute protein expression profiling estimates the relative contributions of transcriptional and translational regulation. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:117–124. doi: 10.1038/nbt1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leskelä T, Tilsala-Timisjärvi A, Kusnetsov J, Neubauer P, Breitenstein A. Sensitive genus-specific detection of legionella by a 16S rRNA based sandwich hybridization assay. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;62:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck M, Malmström JA, Lange V, Schmidt A, Deutsch EW, Aebersold R. Visual proteomics of the human pathogen Leptospira interrogans. Nat Methods. 2009;6:817–823. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt A, Beck M, Malmström J, Lam H, Claassen M, Campbell D, Aebersold R. Absolute quantification of microbial proteomes at different states by directed mass spectrometry. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:510. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yus E, Maier T, Michalodimitrakis K, van Noort V, Yamada T, Chen WH, Wodke JA, Güell M, Martínez S, Bourgeois R, Kühner S, Raineri E, Letunic I, Kalinina OV, Rode M, Herrmann R, Gutiérrez-Gallego R, Russell RB, Gavin AC, Bork P, et al. Impact of genome reduction on bacterial metabolism and its regulation. Science. 2009;326:1263–1268. doi: 10.1126/science.1177263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seybert A, Herrmann R, Frangakis AS. Structural analysis of mycoplasma pneumoniae by cryo-electron tomography. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kühner S, van Noort V, Betts MJ, Leo-Macias A, Batisse C, Rode M, Yamada T, Maier T, Bader S, Beltran-Alvarez P, Castaño-Diez D, Chen WH, Devos D, Güell M, Norambuena T, Racke I, Rybin V, Schmidt A, Yus E, Aebersold R, et al. Proteome organization in a genome-reduced bacterium. Science. 2009;326:1235–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1176343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier T, Schmidt A, Güell M, Kühner S, Gavin AC, Aebersold R, Serrano L. Quantification of mRNA and protein and integration with protein turnover in a bacterium. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:511. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasselbring BM, Jordan JL, Krause RW, Krause DC. Terminal organelle development in the cell wall-less bacterium mycoplasma pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(44):16478–16483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608051103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada H, Yamaguchi M, Chikamatsu K, Aono A, Mitarai S. Structome analysis of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which survives with only 700 ribosomes per 0. 1 fl of cytoplasm PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pang H, Winkler HH. The concentrations of stable RNA and ribosomes in rickettsia prowazekii. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:115–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortiz JO, Förster F, Kürner J, Linaroudis AA, Baumeister W. Mapping 70S ribosomes in intact cells by cryoelectron tomography and pattern recognition. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin SE, Iandolo JJ. Translational control of protein synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:1136–1143. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.3.1136-1143.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flärdh K, Cohen PS, Kjelleberg S. Ribosomes exist in large excess over the apparent demand for protein synthesis during carbon starvation in marine Vibrio sp. strain CCUG 15956 Journal of Bacteriology. 1992;174:6780–6788. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6780-6788.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comolli LR, Baker BJ, Downing KH, Siegerist CE, Banfield JF. Three-dimensional analysis of the structure and ecology of a novel, ultra-small archaeon. The ISME journal. 2009;3:159–167. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biswas SK, Yamaguchi M, Naoe N, Takashima T, Takeo K. Quantitative three-dimensional structural analysis of Exophiala dermadtitidis yeast cells by freeze-substitution and serial ultrathin sectioning. J Electron Microsc. 2003;52:133–143. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/52.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warner JR. The economics of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:437–440. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi M, Namiki Y, Okada H, Mori Y, Furukawa H, Wang J, Ohkusu M, Kawamoto S. Structome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae determined by freeze-substitution and serial ultrathin-sectioning electron microscopy. Microscopy. 2011;60:321–335. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfr052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulak NA, Pichler G, Paron I, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Minimal, encapsulated proteomic-sample processing applied to copy-number estimation in eukaryotic cells. Nat Methods. 2014;11:319–324. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O’Shea EK, Weissman JS. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marguerat S, Schmidt A, Codlin S, Chen W, Aebersold R, Bähler J. Quantitative analysis of fission yeast transcriptomes and proteomes in proliferating and quiescent cells. Cell. 2012;151:671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maclean N. Ribosome numbers in a fission yeast. Nature. 1965;207:322–323. doi: 10.1038/207322a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calzone FJ, Angerer RC, Gorovsky MA. Regulation of protein synthesis in Tetrahymena. Quantitative estimates of the parameters determining the rates of protein synthesis in growing, starved, and starved-deciliated cells. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6887–6898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bourque DP, Boynton JE, Gillham NW. Studies on the structure and cellular location of various ribosome and ribosomal RNA species in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardi. J Cell Sci. 1971;8:153–183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.8.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henderson GP, Gan L, Jensen GJ. 3-D ultrastructure of O. Tauri: electron cryotomography of an entire eukaryotic cell. PLoS One. 2007;2:e749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin J, Gifford EM., Jr The distribution of ribosomes in the vegetative and floral apices of Adonis aestivalis. Can J Bot. 1976;54:2478–2483. doi: 10.1139/b76-265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackson PJ, Lark KG. Ribosomal RNA synthesis in soybean suspension cultures growing in different media. Plant Physiol. 1982;69:234–239. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vassilyev AE. Quantitative ultrastructural data of secretory duct epithelial cells in Rhus toxicodendron. Int J Plant Sci. 2000;161:615–630. doi: 10.1086/314288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsiao TC. Rapid changes in levels of polyribosomes in Zea mays in response to water stress. Plant Physiol. 1970;46:281–285. doi: 10.1104/pp.46.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsiao TC. Ribosomes during development of root cells of Zea mays. Plant Physiol. 1970;45:104–106. doi: 10.1104/pp.45.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buschmann Robert J., Manke Dean J. Morphometric analysis of the membranes and organelles of small intestinal enterocytes. I. Fasted hamster. Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 1981;76(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5320(81)80046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buschmann RJ, Manke DJ. Morphometric analysis of the membranes and organelles of small intestinal enterocytes. II. Lipid-fed hamster. J Ultrastruct Res. 1981;76:15–26. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5320(81)80047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duncan R, Hershey JW. Identification and quantitation of levels of protein synthesis initiation factors in crude HeLa cell lysates by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:7228–7235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao L, Kroenke CD, Song J, Piwnica-Worms D, Ackerman JJ, Neil JJ. Intracellular water-specific MR of microbead-adherent cells: the HeLa cell intracellular water exchange lifetime. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:159–164. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dean PM. Ultrastructural morphometry of the pancreatic -cell. Diabetologia. 1973;9:115–119. doi: 10.1007/BF01230690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weibel ER, Stäubli W, Gnägi HR, Hess FA. Correlated morphometric and biochemical studies on the liver cell. I. Morphometric model, stereologic methods, and normal morphometric data for rat liver. J Cell Biol. 1969;42:68–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ilag LL, Videler H, McKay AR, Sobott F, Fucini P, Nierhaus KH, Robinson CV. Heptameric (L12)6/L10 rather than canonical pentameric complexes are found by tandem MS of intact ribosomes from thermophilic bacteria. PNAS. 2005;102:8192–8197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502193102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gordiyenko Y, Videler H, Zhou M, McKay AR, Fucini P, Biegel E, Müller V, Robinson CV. Mass spectrometry defines the stoichiometry of ribosomal stalk complexes across the phylogenetic tree. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1774–1783. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000072-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garcia MJ, Nuñez MC, Cox RA. Measurement of the rates of synthesis of three components of ribosomes of Mycobacterium fortuitum: a theoretical approach to qRT-PCR experimentation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All checked references of Lynch & Marinov [1] can be downloaded from the respective journal’s websites.