Abstract

RNA structure underpins many essential functions in biology. New chemical reagents and techniques for probing RNA structure in living cells have emerged in recent years. High-throughput, genome-wide techniques such as Structure-seq2 and DMS-MaPseq exploit nucleobase modification by dimethylsulfate (DMS) to obtain complete structuromes, and are applicable to multiple domains of life and conditions. New reagents such as 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), glyoxal, and nicotinoyl azide (NAz) greatly expand the capabilities of nucleobase probing in cells. Additionally, ribose-targeting reagents in selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation and primer extension (SHAPE) detect RNA flexibility in vivo. These techniques, coupled with crosslinking nucleobases in psoralen analysis of RNA interactions and structures (PARIS), provide new and diverse ways to elucidate RNA secondary and tertiary structure in vivo and genome-wide.

INTRODUCTION

Precise folding of RNA into complex structures underlies multiple essential biological processes; for example, those associated with translation [1, 2], gene regulation [3, 4, 5, 6, 7], and mRNA turnover [8]. Studying RNA structure and folding is essential to fully understanding these functions. It therefore comes as no surprise that the past four decades have witnessed development of multiple RNA structure probing strategies. Early work primarily probed RNA structure in vitro, employing ribonucleases that specifically target single- or double-stranded regions of RNAs, and chemical reagents that covalently modify the RNA base [9]. Of these reagents, dimethyl sulfate (DMS), which targets the Watson-Crick face of adenine (A) and cytidine (C) and the Hoogsteen face of guanine (G) when the bases are unpaired and solvent-exposed [10, 11], has received recent emphasis. Similarly, kethoxal modifies solvent-exposed G [12] and carbodiimide 1-cyclohexyl-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide metho-p-toluene sulfonate (CMCT) modifies uracil (U) and to a lesser extent, G [13]. Primer extension allows detection of chemically modified bases [14]. Performing structure probing in vitro necessarily removes biological context due to several factors: absence of RNA-binding proteins, differences in ionic conditions, and inability to replicate intracellular crowding and reactive oxygen species concentration in an in vitro environment, all of which influence RNA structure and folding kinetics [15, 16, 17]. Therefore, identifying probes to study RNA structure in vivo is paramount.

We focus this review on recent developments in in vivo structure probing reagents and examples of their use, developed in our laboratories and others. Large RNases, while useful for in vitro probing assays, cannot cross cell walls or membranes [18], excluding them from in vivo applications. Kethoxal and CMCT also lack membrane permeability and are primarily used in vitro. Conversely, DMS readily penetrates cell walls and membranes, making DMS a crucial tool for in vivo RNA structure probing, but it is limited in providing information only for the Watson-Crick face of A and C, and the Hoogsteen face (N7) of G. Our review discusses recent advances of DMS probing in vivo and genome-wide, development of novel membrane-permeant reagents to probe G and U, and techniques of acylating the 2’-OH of the ribose in vivo.

STRATEGIES FOR PROBING RNA STRUCTURE IN VIVO

Structure probing with dimethyl sulfate (DMS)

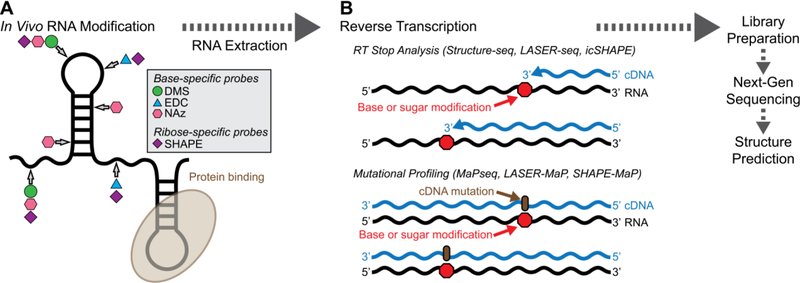

Covalent modification of solvent-exposed RNA bases (Figure 1A) followed by readout of base modifications by detection of consequent reverse transcriptase (RT) stops (Figure 1B, top) underlies many modern in vivo structure probing techniques. Reagents that target the Watson-Crick face provide direct detection of bases that do not participate in base pairing interactions and are not occluded by proteins under the conditions assayed. Bases engaged in canonical or noncanonical interactions that obstruct the Watson-Crick face are protected from modification. Data generated from base-specific structure probes provide to computer programs designed to predict RNA structure [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24] either restraints that give designated sequences an energetic bias for or against base pairing or constraints that force designated sequences to be unpaired.

Figure 1.

Comparison of in vivo structure probing methods. (A) DMS (green circles), EDC (blue triangles), and SHAPE reagents (purple diamonds) react with solvent-accessible, single-stranded RNA. Conversely, NAz (pink hexagons) is agnostic to base pairing and reacts with any solvent-exposed purines. (B) Reverse transcription reactions result in RT stops, which lead to truncated cDNAs or mutations that lead to cDNA extension past the modified RNA base.

Our laboratories developed Structure-seq as a technique to probe in vivo RNA secondary structure in a high-throughput, genome-wide manner [25]. Structure-seq takes advantage of the permeant nature of DMS to probe the Watson-Crick face of single-stranded, solvent-exposed N1-A (i.e. the nitrogen at nucleobase position 1 on A) and N3-C within cells (Figure 2). Our initial experiments treated intact Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings by immersion in buffer containing DMS. Control treatments used buffer of identical composition but lacking DMS. Structure-seq allows for either gene-specific or genome-wide approaches, using specific primers and random hexamer primers, respectively, in RT reactions. Our updated protocol, Structure-seq2, dopes biotinylated dCTP into the dNTP pool, enabling streptavidin purification of cDNAs to be used in library preparations after RT and PCR reactions [26•]. Streptavidin purification provides considerable time savings and increases recovery of cDNAs for downstream steps compared to gel purifications integral to the original Structure-seq protocol. Furthermore, Structure-seq2 specifies T4 DNA ligase for attaching hairpin adapters to the cDNAs, which reduces bias at the ligation site relative to Circligase used in the original protocol [27].

Figure 2.

In vivo RNA structure probing reagents targeting nucleobases and ribose. Sites of targeting on the nucleobase or ribose for each reagent are shown at an atomic level. Arrow directionality represents electron transfer from the nucleophile to the electrophile. “SHAPE” here represents an assortment of ribose-targeting reagents discussed in this review, as all such reagents exhibit similar chemistry. Reaction is prevented if the sites of reactivity are blocked by base pairing or by protection via protein binding or tertiary structure formation.

Both gene-specific and genome-wide Structure-seq approaches have been used recently to examine in vivo RNA structures. The Simon lab used gene-specific Structure-seq to probe within cultured mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells the structure of Xist RNA [28], a >17,000 nucleotide (nt) long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) implicated in X-chromosome gene inactivation during mammalian development [29]. Their updated secondary structure model for the Xist repeat A revealed that the eight 25-nt repeated sequences exhibited high structure conservation across multiple species, concordant with their function in gene repression. Conversely, linkers connecting the repeats have poor conservation. Comparison to previous models derived from in vitro experiments revealed a novel base-pairing conformation within repeat A. Genome-wide Structure-seq, used by the Cao and Ding labs to examine the in vivo rice structurome [30], corroborated earlier Structure-seq studies on Arabidopsis thaliana performed by our groups [25]. In both studies, mRNAs folded differently in vivo on average compared to in silico structure predictions based on in vitro-derived thermodynamic parameters [25, 30]. Regulatory genes folded most similarly to predicted structures, indicating a high degree of stability, while genes involved in redox homeostasis, signal transduction, and photosynthesis differed significantly from predictions. Interestingly, Cao and Ding found that GC content had a lower impact on RNA structure compared to natural methylation events at N6-A (m6A), which have been found to destabilize RNA structure [31, 32]. In rice, structure destabilization from m6A modifications appeared limited primarily to 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) [30]. Comparing the rice and Arabidopsis mRNA structuromes revealed that increased amount of RNA structure present in rice was not correlated with GC content, despite rice having significantly higher GC content relative to Arabidopsis.

As RNA structure is sensitive to stresses such as temperature and salt concentration, efforts to measure the effects of such abiotic stresses on the in vivo RNA structurome is expected to provide valuable biological insights. Our labs have recently examined the effect of acute heat stress on the rice structurome using DMS treatment and Structure-seq, finding heat-induced unfolding of many mRNAs [33••]. We found that in the absence of heat shock, 3’ UTRs are more structured than 5’ UTRs or coding sequences (CDS); concomitantly, 3’ UTRs exhibit greater unfolding under heat shock than the 5’ UTR or CDS. However, we found no correlation between heat-induced RNA unfolding and the extent of translation immediately after this brief heat stress. Rather, RNA unfolding correlated with a decrease in mRNA abundance. We hypothesized that heat shock destabilized base pairing between the U-rich 3’ UTRs and the poly(A) tail, which allowed the 3’-to-5’ RNA-degrading exosome access to free 3’ ends. Furthermore, when we assessed the degradome, which contains 5’-to-3’ RNA degradation fragments, we found an enrichment of transcripts exhibiting heat-induced unfolding.

Mutational profiling with sequencing (MaPseq), a recently developed alternative to RT-stop analysis methods such as Structure-seq, exploits the tendency of some highly processive RT enzymes to read through RNA base modifications and insert mutations in the cDNA across from the modified site (Figure 1B, bottom) [34•]. Here, thermostable group II reverse transcriptase (TGIRT) [35] replaces more traditional RT enzymes such as Superscript III used in Structure-seq and similar techniques. As with Structure-seq, MaPseq can be applied in a gene-specific or genome-wide manner, with detected mutations equated to unpaired nucleotides. One crucial advantage of DMS-MaPseq is that it removes the requirement for tailoring DMS reactions to achieve one modified base per RNA molecule (or one modification per ~100 bases), known as single-hit kinetics. TGIRT can read through multiple DMS modifications on a single molecule, increasing sequencing depth at a given modified base. Furthermore, MaPseq eliminates signal decay after endogenous base modifications compared to RT-stop assays that use a single gene-specific primer or oligo-dT. Other highly processive RTs can be used for MaPseq if the chosen RT has a low mismatch rate for unmodified nucleobases. DMS-MaPseq has been used genome-wide to examine the yeast structurome and in a targeted manner to examine mRNAs within Drosophila melanogaster ovaries, the latter illustrating amenability of DMS probing within intact animal tissues [34•]. Interestingly, RT preferentially forms mutations at DMS-modified C nucleobases and stops at DMS-modified A nucleobases [36], which may explain the apparently higher DMS reactivity with A versus C observed with RT stop analysis. This bias was retained even when using a different ligase during library preparations or using different RT enzymes [36].

New base-specific structure probes

One critical drawback of DMS has been that it only gives data on Watson-Crick pairing of A and C. The lack of a reliable probe for G and U base pairing has limited the reliability of predicted RNA structures. Notably, new reagents were recently developed to bridge this information gap in structure prediction. The water-soluble carbodiimide 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) has emerged as a potent in vivo probe for U and G, reacting with the Watson-Crick face at N3-U and N1-G (Figure 2) [37••, 38••]. Similar to CMCT reactions in vitro, EDC slightly favors reactivity with U over G. Furthermore, EDC reacts more readily with G at neutral pH as compared to glyoxal that prefers higher pH (see below), thus providing significantly more data in cellular conditions. Importantly, EDC readily penetrates cell walls and membranes, and has been used to probe RNAs within multiple domains of life, including Bacillus subtilis, rice, and cultured MEF cells [37••, 38••]. Recent in vivo probing of Xist RNA in MEF cells combined EDC and DMS probing for the first time, providing a revised structure model of a ~500 nt region, including some novel interactions not featured in previous in vitro or in vivo DMS-only models [38••]. Overall, the development of EDC combined with traditional DMS approaches allows in vivo probing of all four RNA bases. We also recently identified glyoxal reagents as probes for N1-G and to a lesser extent N1-A and N3-C (Figure 2) [39••]. Hydrophobic variants, such as methylglyoxal and phenylglyoxal, generally give increased reactivity, presumably by increasing membrane permeability. In vivo structure probing within rice, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and cultured MEF cells have established glyoxal reactivity within multiple domains of life [38••, 39••]. Moreover, the combination of glyoxal and EDC offers the potential of identifying anionic guanines in vivo and genome-wide [37••].

RNA structure is not limited to Watson-Crick interactions; as such, the ability to probe in vivo base interactions not involving the Watson-Crick face is extremely desirable. Nicotinoyl azide (NAz) allows probing of the C8-G and C8-A positions, which are opposite the Watson-Crick face (Figure 2), very rapidly upon UV light excitation in a process termed light activated structural examination of RNA (LASER) [40••]. The NAz adduct induces an anti-to-syn base isomerization, allowing detection of base modifications via RT stop assays. Unlike other reagents, NAz reacts equally with solvent-exposed C8 of purines in both paired and unpaired conformations. LASER probing thus examines nucleobase solvent accessibility, potentially identifying regions lacking RNA-protein interactions, ligand binding to riboswitches, or RNA tertiary structure formation. Sensitivity of LASER reactivity to protein binding and tertiary structure formation but not to Watson-Crick base-pairing makes NAz a particularly valuable reagent. Gene-specific LASER probing within human HeLa cells allowed accurate mapping of RNA-protein interactions in 18S rRNA and U1 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein (U1snRNP) complexes. Combining LASER probing with high-throughput sequencing allows genome-wide examination of either RT stops (LASER-Seq) or mutational profiles (LASER-MaP) [41•].

Structure probing with ribose-reactive reagents

In vivo probing with DMS and EDC provides information on all four bases in an RNA structure and can be done in different biological contexts. Another way to cover information on all nucleotides is via selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation and primer extension (SHAPE) reagents, which target the ribose sugar (Figure 2) to enable base-agnostic in vivo structure probing [42]. Greater distance between the 2’-hydroxyl (2’-OH) on ribose and its 3’-group, a property of flexible regions of RNA, allows breaking of 2’-OH-to-3’-O hydrogen bonding and thus sufficient nucleophilicity for SHAPE reagent reactivity. Since nucleobase pairing causes conformational rigidity, RNA regions exhibiting high SHAPE reactivity typically correlate with single-strandedness.

Similar to the base-targeting reagents, SHAPE reagents can be used with either conventional RT-stop assays (Figure 1B, top) or mutational profiling (Figure 1B, bottom) to infer in vivo RNA structures in either a gene-specific or a genome-wide manner when combined with next-generation sequencing [43]. Since the invention of the first SHAPE reagent, N-methylisatoic anhydride (NMIA) by the Weeks group [42], multiple SHAPE reagents have been developed and utilized to probe RNA structure in vivo. Of special importance to in vivo SHAPE mapping are the acylimidazole reagents 2-methylnicotinic acid imidazolide (NAI) and 2-methyl-3-furoic acid imidazolide (FAI) reagents developed by Spitale, Kool, and Chang, which have been used to study RNAs in animal, yeast, and bacterial cells [44]. These investigators subsequently developed NAI-N3, an NAI derivative functionalized with azido groups, to enable enrichment of NAI-reacted RNAs by click chemistry. This led to in vivo click-selective SHAPE probing (icSHAPE), which was applied to examine RNA structuromes of cultured mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) [45], revealing general unfolding of mRNAs relative to other types of RNAs such as lncRNAs and primary miRNA precursors. Despite this, mRNAs were more structured overall than previously reported from DMS probing [46]. Furthermore, icSHAPE, in conjunction with ribosome profiling and crosslinking methods, uncovered unique structural rearrangements at sites of regulatory protein binding and natural m6A modifications [45]. Further investigation into m6A modifications and their effects on RNA structure and interactions with RNA-binding proteins (RBP) were performed by the Chang and Zhang groups using icSHAPE [47]. They identified in cultured mESCs and human HEK293 cell lines proteins that exhibited reduced binding to RNA regions destabilized by natural m6A modifications. This was a novel characterization relative to proteins known to favor binding to m6A-destabilized RNA such as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (hnRNP C) [32].

Similar to DMS-MaP described above, combining mutational profiling with SHAPE in SHAPE-MaP [48, 49] allows for correlated information in a single read and avoids signal decay from a gene-specific primer and the need to work under single-hit kinetics. However, mutational profiling methods, such as DMS-MaP and SHAPE-MaP, require increased sequencing depth at modified positions in order to distinguish structure-induced mutations from stochastic RT mutagenesis events occurring across from an unreacted base or sequencing errors. Whereas icSHAPE used acylimidazole reagents NAI and FAI, SHAPE-MaP uses primarily 1-methyl-7-nitroisatoic anhydride (1M7) [48]. SHAPE-MaP was recently used by Laederach and co-workers to demonstrate in human cells specific regions of structure rearrangements correlating with binding sites for zipcode binding protein (ZBP1) [50], which is involved in mRNA localization and translation [51]. In an examination of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV) polyadenylated nuclear (PAN) RNA in nuclear, cytoplasmic, and viral environments, Whitby and Le Grice used SHAPE-MaP to determine the secondary structure of PAN RNA and to extensively characterize its protein binding sites [52•]. The authors found that PAN RNA retained its structure within virus particles, though the structures differed between viral and cellular contexts.

In a study of bacterial RNA regulatory features, the Weeks lab used SHAPE-MaP to locate in the Escherichia coli transcriptome novel protein binding motifs in structurally conserved elements of 5’ and 3’ UTRs [53••]. These conserved structural elements counter otherwise high structural heterogeneity found within Escherichia coli mRNA. Furthermore, the authors linked low mRNA structure within the Shine-Dalgarno site and proximal regions (RBS) and favorable unfolding kinetics of that region to increased translational efficiency (TE); conversely, highly structured RBS regions exhibited low TE. They also indicated that structure within the downstream coding regions had less impact on TE than structure in the RBS.

Intracellular reactivity varies drastically for the current selection of SHAPE reagents. NMIA, the first reagent developed, is suboptimal for in vivo use as evidenced by undetectable reactivity in mESCs when probing highly abundant 5S rRNA [44]. Newer SHAPE reagents have demonstrated in vivo reactivity within multiple organisms, although use of these reagents requires consideration of their different chemical properties [54•]. All SHAPE reagents, which acylate the 2’-O, also react with water; this hydrolysis quenches the reagent but also limits its intracellular half-life. Hydrolysis half-life in aqueous solution ranges from 2 min for 1M7 to 33 min for NAI and 73 min for FAI [54•]. A shorter half-life eliminates the need for reagent quenching but this can occur at the expense of incomplete reaction with RNA. Multiple researchers have reported successful in vivo reactivity with high signal using 1M7, particularly in Gram negative Escherichia coli which has two cell membranes [43, 55]. Conversely, in vivo probing of mESCs revealed robust NAI and FAI reactivity and comparatively weaker 1M7 reactivity, with significantly lower signal-to-background, based on normalized band intensity, when using RT-stop analysis and gel electrophoresis [54•]. Permeabilizing the cell membrane increased 1M7 reactivity but had no effect on reactivity for NAI-N3, supporting that 1M7 was essentially membrane impermeable in living cells.

Discussion and Conclusion

There is an increasing array of chemicals for studying RNA structure in vivo. These reagents allow researchers to decode nucleobase pairing status and backbone flexibility genome-wide and in vivo. In this review, we described recent advances that include the novel U and G base-targeting reagent EDC that, when combined with the legacy but equally valuable reagent DMS, can probe all four nucleobases in vivo. Detecting all unpaired and solvent-exposed nucleobases should greatly improve the restraint data used to characterize and computationally predict RNA structures; see for instance changes in probing the lncRNA Xist (Figure 3). SHAPE probing provides complementary information about the sugar portion of the backbone, from which base pairing status can be inferred. However, information gaps still remain, particularly regarding the ability to discern protein interactions from base pairing. A new technique that uses psoralen to crosslink two nucleobases provides direct information on nucleotide proximity, giving data on which bases are paired both within and between RNAs. In particular, psoralen analysis of RNA interactions and structures (PARIS) [56] was used to identify interactions between small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) and rRNA, as well as between the Xist ribonucleoprotein complex and the silencing factor Spen [57]. Nucleotide-proximity probing combined with available methods to exhaustively identify unpaired regions enables comprehensive characterization, and therefore far more accurate prediction of in vivo RNA secondary structure than ever before. In the future, the most definitive studies of in vivo RNA structure will utilize multiple probing techniques, and may do so at the single-molecule level such that averaging of information is eliminated. Additional crystal or cryo-EM structures will facilitate independent verification of structures, particularly if future 3D structures can be generated under in vivo or in vivo-like conditions.

Figure 3.

Comparison of a previous Xist structure model (left) generated from DMS probing using targeted Structure-seq data only [28], and the updated Xist model (right) generated from DMS using targeted Structure-seq data combined with DMS-MaPseq and EDC probing data [38]. Differences in base pairing between the two models are shown by magenta-colored dashes between the bases in each structure. Adapted from [28,38].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The National Science Foundation Plant Genome Research Program supported D. Mitchell under NSF-IOS-1612170 and research on RNA structure in the P. C. Bevilacqua and S. M. Assmann labs under NSF-IOS-1339282. The National Institutes of Health supported research in the Bevilacqua lab under 1R35GM127064.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Noller HF, Hoffarth V, Zimniak L: Unusual resistance of peptidyl transferase to protein extraction procedures. Science 1992, 256:1416–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusupov MM, Yusupova GZ, Baucom A, Lieberman K, Earnest TN, Cate JH, Noller HF: Crystal structure of the ribosome at 5.5 A resolution. Science 2001, 292:883–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanofsky C: Attenuation in the control of expression of bacterial operons. Nature 1981, 289:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altuvia S, Kornitzer D, Teff D, Oppenheim AB: Alternative mRNA structures of the cIII gene of bacteriophage lambda determine the rate of its translation initiation. J Mol Biol 1989, 210:265–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naville M, Gautheret D: Transcription attenuation in bacteria: theme and variations. Brief Funct Genomics 2010, 9:178–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peselis A, Serganov A: Themes and variations in riboswitch structure and function. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1839:908–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnwal RP, Loh E, Godin KS, Yip J, Lavender H, Tang CM, Varani G: Structure and mechanism of a molecular rheostat, an RNA thermometer that modulates immune evasion by Neisseria meningitidis. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44:9426–9437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wan Y, Qu K, Ouyang Z, Kertesz M, Li J, Tibshirani R, Makino DL, Nutter RC, Segal E, Chang HY: Genome-wide measurement of RNA folding energies. Mol Cell 2012, 48:169–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehresmann C, Baudin F, Mougel M, Romby P, Ebel JP, Ehresmann B: Probing the structure of RNAs in solution. Nucleic Acids Res 1987, 15:9109–9128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peattie DA, Gilbert W: Chemical probes for higher-order structure in RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1980, 77:4679–4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroder AR, Baumstark T, Riesner D: Chemical mapping of co-existing RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res 1998, 26:3449–3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noller HF, Chaires JB: Functional modification of 16S ribosomal RNA by kethoxal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1972, 69:3115–3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziehler WA, Engelke DR: Probing RNA structure with chemical reagents and enzymes. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem 2001, Chapter 6:Unit 6.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris KA Jr., Crothers DM, Ullu E: In vivo structural analysis of spliced leader RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei and Leptomonas collosoma: a flexible structure that is independent of cap4 methylations. RNA 1995, 1:351–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leamy KA, Assmann SM, Mathews DH, Bevilacqua PC: Bridging the gap between in vitro and in vivo RNA folding. Q Rev Biophys 2016, 49:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leamy KA, Yennawar NH, Bevilacqua PC: Cooperative RNA folding under cellular conditions arises from both tertiary structure stabilization and secondary structure destabilization. Biochemistry 2017, 56:3422–3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaug AJ, Cech TR: Analysis of the structure of Tetrahymena nuclear RNAs in vivo: telomerase RNA, the self-splicing rRNA intron, and U2 snRNA. RNA 1995, 1:363–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knapp G: Enzymatic approaches to probing of RNA secondary and tertiary structure. Methods Enzymol 1989, 180:192–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reuter JS, Mathews DH: RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouyang Z, Snyder MP, Chang HY: SeqFold: genome-scale reconstruction of RNA secondary structure integrating high-throughput sequencing data. Genome Res 2013, 23:377–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norris M, Kwok CK, Cheema J, Hartley M, Morris RJ, Aviran S, Ding Y: FoldAtlas: a repository for genome-wide RNA structure probing data. Bioinformatics 2017, 33:306–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tack DC, Tang Y, Ritchey LE, Assmann SM, Bevilacqua PC: StructureFold2: Bringing chemical probing data into the computational fold of RNA structural analysis. Methods 2018, 143:12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews RJ, Roche J, Moss WN: ScanFold: an approach for genome-wide discovery of local RNA structural elements-applications to Zika virus and HIV. PeerJ 2018, 6:e6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroeder SJ: Challenges and approaches to predicting RNA with multiple functional structures. RNA 2018, 24:1615–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding Y, Tang Y, Kwok CK, Zhang Y, Bevilacqua PC, Assmann SM: In vivo genome-wide profiling of RNA secondary structure reveals novel regulatory features. Nature 2014, 505:696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •26.Ritchey LE, Su Z, Tang Y, Tack DC, Assmann SM, Bevilacqua PC: Structure-seq2: sensitive and accurate genome-wide profiling of RNA structure in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45:e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors detail various data quality and time-savings improvements to the genome-wide, high-throughput RNA structure determination technique Structure-seq. Biotinylated nucleotides doped into the reverse transcription reaction increase cDNA retention during purification steps, while replacing Circligase with T4 DNA ligase reduces nucleotide bias during sequencing.

- 27.Kwok CK, Ding Y, Sherlock ME, Assmann SM, Bevilacqua PC: A hybridization-based approach for quantitative and low-bias single-stranded DNA ligation. Anal Biochem 2013, 435:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang R, Moss WN, Rutenberg-Schoenberg M, Simon MD: Probing Xist RNA structure in cells using targeted Structure-seq. PLoS Genet 2015, 11:e1005668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahakyan A, Yang Y, Plath K: The role of Xist in X-chromosome dosage compensation. Trends Cell Biol 2018, 28:999–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng H, Cheema J, Zhang H, Woolfenden H, Norris M, Liu Z, Liu Q, Yang X, Yang M, Deng X, et al. : Rice in vivo RNA structurome reveals RNA secondary structure conservation and divergence in plants. Mol Plant 2018, 11:607–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roost C, Lynch SR, Batista PJ, Qu K, Chang HY, Kool ET: Structure and thermodynamics of N6-methyladenosine in RNA: a spring-loaded base modification. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137:2107–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T: N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 2015, 518:560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••33.Su Z, Tang Y, Ritchey LE, Tack DC, Zhu M, Bevilacqua PC, Assmann SM: Genome-wide RNA structurome reprogramming by acute heat shock globally regulates mRNA abundance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:12170–12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study examines the effects of acute heat shock on the rice seedling mRNA structurome using in vivo DMS probing and genome-wide Structure-seq analysis. The authors reveal extensive unfolding of structured 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) relative to 5’ UTRs and coding sequences, as well as anti-correlation of mRNA unfolding and mRNA abundance after heat shock.

- •34.Zubradt M, Gupta P, Persad S, Lambowitz AM, Weissman JS, Rouskin S: DMS-MaPseq for genome-wide or targeted RNA structure probing in vivo. Nat Methods 2017, 14:75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study represents the first application of mutational profiling to in vivo DMS structure probing and the first application of DMS probing to intact animal tissue (Drosophila melanogaster ovaries) instead of cultured animal cells. The authors further developed a targeted technique of DMS-MaPseq and applied it to examining multiple isoforms of yeast ribosomal RNA.

- 35.Mohr S, Ghanem E, Smith W, Sheeter D, Qin Y, King O, Polioudakis D, Iyer VR, Hunicke-Smith S, Swamy S, et al. : Thermostable group II intron reverse transcriptase fusion proteins and their use in cDNA synthesis and next-generation RNA sequencing. RNA 2013, 19:958–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sexton AN, Wang PY, Rutenberg-Schoenberg M, Simon MD: Interpreting reverse transcriptase termination and mutation events for greater insight into the chemical probing of RNA. Biochemistry 2017, 56:4713–4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••37.Mitchell D 3rd, Renda AJ, Douds CA, Babitzke P, Assmann, Bevilacqua PC: In vivo RNA structural probing of uracil and guanine base-pairing by 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC). RNA 2019, 25:147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Novel development of the water-soluble carbodiimide EDC as an in vivo RNA structural probe targeting uracil (U) and guanine (G). Probing of intact Escherichia coli cells and rice seedlings without prior membrane permeabilization demonstrated applicability of EDC across multiple domains of life. Further, EDC probing in conjunction with glyoxal probing indicated potential naturally occurring anionic guanines in living cells.

- ••38.Wang PY, Sexton AN, Culligan WJ, Simon MD: Carbodiimide reagents for the chemical probing of RNA structure in cells. RNA 2019, 25:135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Novel development of the water-soluble carbodiimide EDC as an in vivo RNA structural probe targeting uracil (U) and guanine (G). Application of EDC to probe the structure of Xist lncRNA within intact cultured mouse embryonic stem cells led to improvements to prior Xist structure models. This study represents the first combination of EDC and DMS probing data, providing Watson-Crick pairing status of all four bases of an RNA.

- ••39.Mitchell D 3rd, Ritchey LE, Park H, Babitzke P, Assmann SM, Bevilacqua PC: Glyoxals as in vivo RNA structural probes of guanine base-pairing. RNA 2018, 24:114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors developed glyoxal and glyoxal derivatives as in vivo RNA structural probes targeting guanine bases, demonstrating that glyoxal and hydrophobic derivatives readily crosses intact cell walls and membranes to react with the unpaired and solvent-exposed amidine functionality of guanine (G), adenine (A), and cytosine (C). Use of glyoxal to probe ribosomal RNAs within Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and rice demonstrated its applicability in multiple domains of life.

- ••40.Feng C, Chan D, Joseph J, Muuronen M, Coldren WH, Dai N, Correa IR Jr., Furche F, Hadad CM, Spitale RC: Light-activated chemical probing of nucleobase solvent accessibility inside cells. Nat Chem Biol 2018, 14:276–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors developed nicotinoyl azide (NAz) as a novel in vivo probe of RNA solvent accessibility that targets the C8 position of purine nucleobases. Through both in vitro experiments and in vivo probing of human HeLa cells, the authors demonstrated that NAz enables accurate reporting of changes in RNA solvent accessibility due to metabolite-induced structural changes. Insensitivity of NAz reactivity to Watson-Crick base pairing status makes it useful for sensing protein-RNA interactions.

- •41.Zinshteyn B, Chan D, England W, Feng C, Green R, Spitale RC: Assaying RNA structure with LASER-Seq. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47:43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study combines the authors’ in vivo NAz probing (LASER) in reference 36 with both RT-stop analysis (LASER-Seq) and mutational profiling (LASER-MaP) to provide genome-wide, high-throughput reporting of RNA structure and solvent accessibility. The authors use LASER in vitro to characterize translation factor interactions with nucleotides in Escherichia coli 23S rRNA and in vivo to probe rRNA in cultured human K562 cells.

- 42.Merino EJ, Wilkinson KA, Coughlan JL, Weeks KM: RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution by selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation and primer extension (SHAPE). J Am Chem Soc 2005, 127:4223–4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watters KE, Yu AM, Strobel EJ, Settle AH, Lucks JB: Characterizing RNA structures in vitro and in vivo with selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension sequencing (SHAPE-Seq). Methods 2016, 103:34–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spitale RC, Crisalli P, Flynn RA, Torre EA, Kool ET, Chang HY: RNA SHAPE analysis in living cells. Nat Chem Biol 2013, 9:18–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spitale RC, Flynn RA, Zhang QC, Crisalli P, Lee B, Jung JW, Kuchelmeister HY, Batista PJ, Torre EA, Kool ET, Chang HY: Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature 2015, 519:486–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rouskin S, Zubradt M, Washietl S, Kellis M, Weissman JS: Genome-wide probing of RNA structure reveals active unfolding of mRNA structures in vivo. Nature 2014, 505:701–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun L, Fazal FM, Li P, Broughton JP, Lee B, Tang L, Huang W, Kool ET, Chang HY, Zhang QC: RNA structure maps across mammalian cellular compartments. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegfried NA, Busan S, Rice GM, Nelson JA, Weeks KM: RNA motif discovery by SHAPE and mutational profiling (SHAPE-MaP). Nat Methods 2014, 11:959–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smola MJ, Weeks KM: In-cell RNA structure probing with SHAPE-MaP. Nat Protoc 2018, 13:1181–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods CT, Lackey L, Williams B, Dokholyan NV, Gotz D, Laederach A: Comparative visualization of the RNA suboptimal conformational ensemble in vivo. Biophys J 2017, 113:290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawrence JB, Singer RH: Intracellular localization of messenger RNAs for cytoskeletal proteins. Cell 1986, 45:407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •52.Sztuba-Solinska J, Rausch JW, Smith R, Miller JT, Whitby D, Le Grice SFJ: Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus polyadenylated nuclear RNA: a structural scaffold for nuclear, cytoplasmic and viral proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45:6805–6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive characterization of viral polyadenylated nuclear (PAN) RNA structure and protein binding sites is performed using SHAPE-MaP. Importantly, this study compares structures formed by PAN RNA within nuclear, cytoplasmic, and viral environments, finding differences in RNA structure among these contexts.

- ••53.Mustoe AM, Busan S, Rice GM, Hajdin CE, Peterson BK, Ruda VM, Kubica N, Nutiu R, Baryza JL, Weeks KM: Pervasive regulatory functions of mRNA structure revealed by high-resolution SHAPE probing. Cell 2018, 173:181–195e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; SHAPE-MaP is used in an extensive study of the Escherichia coli mRNA structurome, where the authors reveal novel motifs for protein binding to structurally conserved UTRs. The study finds a link between decreased mRNA structure and increased translational efficiency (TE) for certain mRNA regions. Furthermore, the authors demonstrate that RNA folding kinetics correlate with TE and that mRNA structure mediates translational coupling between a gene and its downstream gene.

- •54.Lee B, Flynn RA, Kadina A, Guo JK, Kool ET, Chang HY: Comparison of SHAPE reagents for mapping RNA structures inside living cells. RNA 2017, 23:169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Membrane permeability and in vivo reactivity of multiple ribose-targeting SHAPE reagents are evaluated by in vitro and in vivo probing of mouse embryonic stem cell 5S rRNA. The authors observe that the acylimidazole reagents NAI and FAI give greater in vivo reactivity compared to 1M7.

- 55.McGinnis JL, Weeks KM: Ribosome RNA assembly intermediates visualized in living cells. Biochemistry 2014, 53:3237–3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu Z, Zhang QC, Lee B, Flynn RA, Smith MA, Robinson JT, Davidovich C, Gooding AR, Goodrich KJ, Mattick JS, et al. : RNA duplex map in living cells reveals higher-order transcriptome structure. Cell 2016, 165:1267–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monfort A, Di Minin G, Postlmayr A, Freimann R, Arieti F, Thore S, Wutz A: Identification of Spen as a crucial factor for Xist function through forward genetic screening in haploid embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep 2015, 12:554–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]